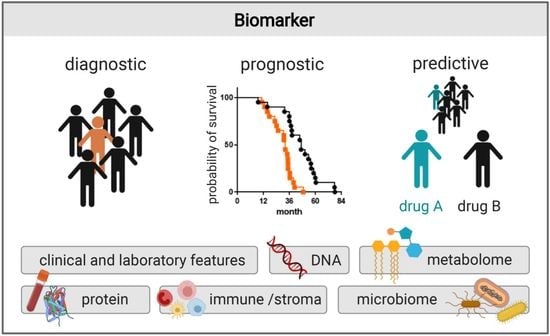

Recent Discoveries of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers for Pancreatic Cancer

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Clinical and Laboratory Features as Biomarkers

3. Protein Biomarkers

4. DNA Biomarkers

5. Metabolomic Biomarkers

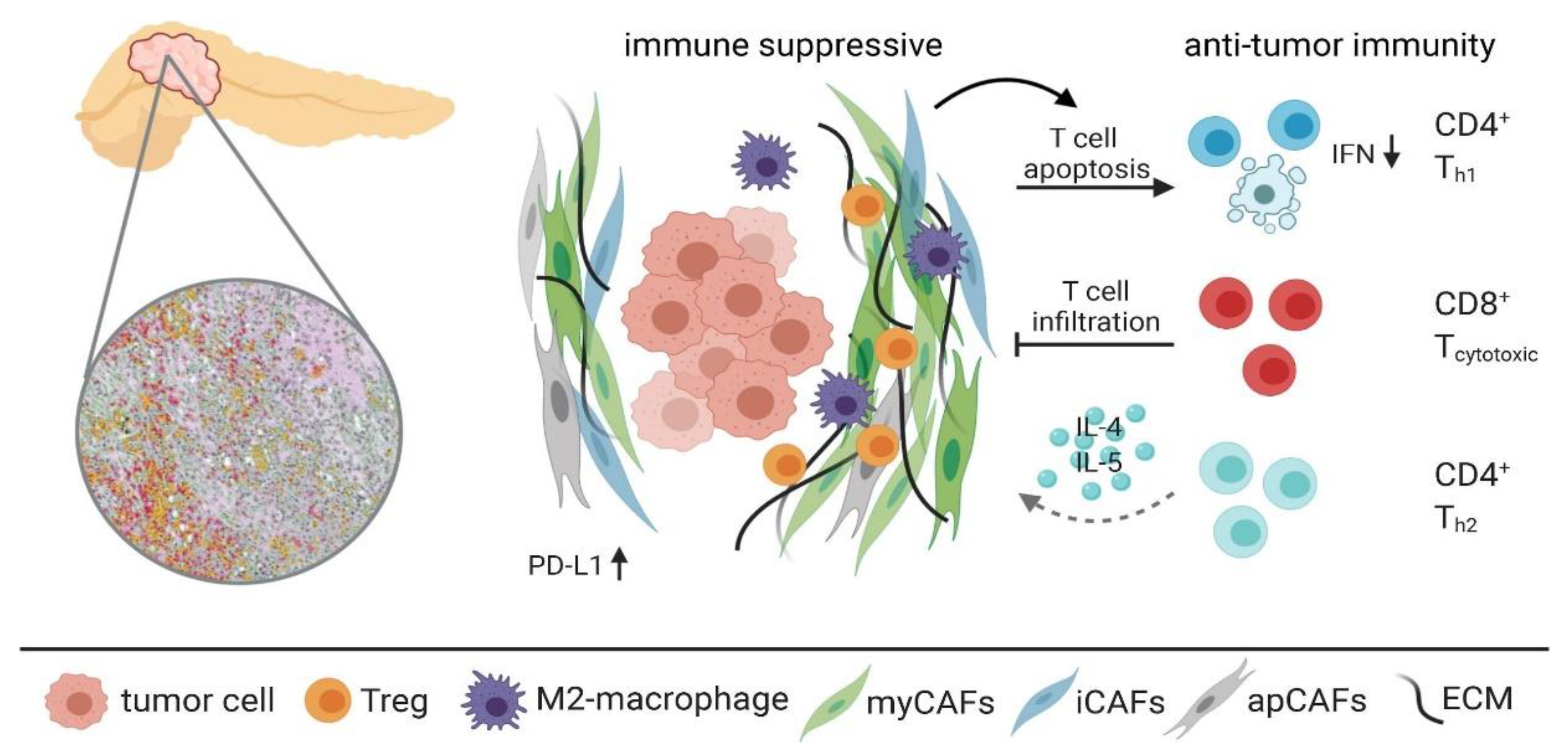

6. Immune and Stroma Biomarkers

7. Microbiome Biomarkers

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dyba, T.; Randi, G.; Bettio, M.; Gavin, A.; Visser, O.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 103, 356–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, A.J.; Colburn, W.A.; DeGruttola, V.G.; DeMets, D.L.; Downing, G.J.; Hoth, D.F.; Oates, J.A.; Peck, C.C.; Schooley, R.T.; Spilker, B.A.; et al. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharm. 2001, 69, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Löhr, M. Is it possible to survive pancreatic cancer? Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 3, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minicozzi, P.; Cassetti, T.; Vener, C.; Sant, M. Analysis of incidence, mortality and survival for pancreatic and biliary tract cancers across Europe, with assessment of influence of revised European age standardisation on estimates. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 55, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Grimes, N.; Farid, S.; Morris-Stiff, G. Inflammatory response related scoring systems in assessing the prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2014, 13, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.C. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: A decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.J.; Morrison, D.S.; Talwar, D.; Balmer, S.M.; Fletcher, C.D.; O’Reilly, D.S.J.; Foulis, A.K.; Horgan, P.G.; Mcmillan, D.C. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 2633–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.J.; Hu, Z.G.; Shi, W.X.; Deng, T.; He, S.Q.; Yuan, S.G. Prognostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 2807–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Cheng, S.; Fathy, A.H.; Qian, H.; Zhao, Y. Prognostic value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A comprehensive meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies. Onco. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deng, Q.L.; Dong, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.Y.; Ying, H.F.; Li, Z.S.; Shen, X.H.; Guo, Y.B.; Meng, Z.Q.; Yu, J.M.; et al. Development and Validation of a Nomogram for Predicting Survival in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, A.; Salgado, M.; García, A.; Buxò, E.; Vera, R.; Adeva, J.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Quintero, G.; Llorca, C.; Cañabate, M.; et al. Prognostic factors for survival with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer in real-life practice: The ANICE-PaC study. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamada, T.; Nakai, Y.; Yasunaga, H.; Isayama, H.; Matsui, H.; Takahara, N.; Sasaki, T.; Takagi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Yagioka, H.; et al. Prognostic nomogram for nonresectable pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 1943–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, W.; Miao, D.L.; Chen, L. Nomogram for predicting survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vernerey, D.; Huguet, F.; Vienot, A.; Goldstein, D.; Paget-Bailly, S.; Van Laethem, J.L.; Glimelius, B.; Artru, P.; Moore, M.J.; André, T.; et al. Prognostic nomogram and score to predict overall survival in locally advanced untreated pancreatic cancer (PROLAP). Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fornaro, L.; Leone, F.; Vienot, A.; Casadei-Gardini, A.; Vivaldi, C.; Lièvre, A.; Lombardi, P.; De Luca, E.; Vernerey, D.; Sperti, E.; et al. Validated Nomogram Predicting 6-Month Survival in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Receiving First-Line 5-Fluorouracil, Oxaliplatin, and Irinotecan. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2019, 18, e394–e401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goonetilleke, K.S.; Siriwardena, A.K. Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 33, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.K.; Wei, L.; Trolli, E.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Elevated baseline CA19-9 levels correlate with adverse prognosis in patients with early- or advanced-stage pancreas cancer. Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 3101–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, G.; Jin, K.; Guo, M.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Long, J.; Liu, L.; Xu, J.; et al. Patients with normal-range CA19-9 levels represent adistinct subgroup of pancreatic cancer patients. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabernero, J.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Ganju, V.; Weekes, C.; Scheithauer, W.; Ramanathan, R.K.; Goldstein, D.; Penenberg, D.N.; et al. Prognostic Factors of Survival in a Randomized Phase III Trial (MPACT) of Weekly nab- Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine Versus Gemcitabine Alone in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Oncologist 2015, 20, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wasan, H.S.; Springett, G.M.; Chodkiewicz, C.; Wong, R.; Maurel, J.; Barone, C.; Rosbrook, B.; Ricart, A.D.; Kim, S.; Spano, J.P. CA 19-9 as a biomarker in advanced pancreatic cancer patients randomised to gemcitabine plus axitinib or gemcitabine alone. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Satake, K.; Chung, Y.S.; Yokomatsu, H.; Nakata, B.; Tanaka, H.; Sawada, T.; Nishiwaki, H.; Umeyama, K. A clinical evaluation of various tumor markers for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Pancreatol. 1990, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Ji, S.; Zhang, B.; Ni, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. Diagnostic and prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 4591–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjövall, K.; Nilsson, B.; Einhorn, N. The significance of serum CA 125 elevation in malignant and nonmalignant diseases. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002, 85, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, L.; Cavallini, G.; Zordan, D.; Rizzotti, P.; Rigo, L.; Brocco, G.; Perobelli, L.; Zanchetta, M.; Pederzoli, P.; Scuro, L.A. A clinical evaluation of monoclonal (CA19-9, CA50, CA12-5) and polyclonal (CEA, TPA) antibody-defined antigens for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 1988, 3, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattani, A.M.; Mandeli, J.; Bruckner, H.W. Tumor markers in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 1996, 78, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.P.; Sandanayake, N.S.; Jenkinson, C.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Apostolidou, S.; Fourkala, E.O.; Camuzeaux, S.; Blyuss, O.; Gunu, R.; Dawnay, A.; et al. Serum CA19-9 is significantly upregulated up to 2 years before diagnosis with pancreatic cancer: Implications for early disease detection. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Tumor markers CA19-9, CA242 and CEA in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 11683–11691. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q.; Zhao, Y.-P.; Yang, Y.-C.; Li, L.-J.; Long, X.; Han, S.-M. Combined detection of serum tumor markers for differential diagnosis of solid lesions located at the pancreatic head. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2007, 6, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Lu, X.H.; Xu, T.; Qian, J.M.; Zhao, P.; Guo, X.Z.; Yang, X.O.; Jiang, W.J. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of serum tumor markers, and fecal k-ras and p53 gene mutations for pancreatic cancer. Chin. J. Dig. Dis. 2006, 7, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.T.; Tao, H.Q.; Zou, S.C. Detection of serum tumor markers in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2004, 3, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.G.; Bai, X.F.; Mao, Y.L.; Shao, Y.F.; Wu, J.X.; Shan, Y.; Wang, C.F.; Wang, J.; Tian, Y.T.; Liu, Q.; et al. The clinical value of serum CEA, CA19-9, and CA242 in the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 31, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, W. The clinical utility of the CA 19-9 tumor-associated antigen. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1990, 85, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.B.; Qin, S.Y.; Chen, W.; Luo, W.; Jiang, H.X. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 for differential diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 4323–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraker, N.; Hot, S.; Polat, Y.; Höbek, A.; Gençler, N.; Urhan, N. CEA, CA 19-9, and CA 125 in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant pancreatic diseases with or without jaundice. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 95, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwik, G.; Wallner, G.; Skoczylas, T.; Ciechański, A.; Zinkiewicz, K. Cancer antigens 19-9 and 125 in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic mass lesions. Arch. Surg. 2006, 141, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, T.; Kawa, S.; Tokoo, M.; Oguchi, H.; Kiyosawa, K.; Furuta, S.; Kanai, M.; Homma, T. Comparative study of CA-50 (time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay), span-1, and CA19-9 in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 26, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gupta, S.; Pandey, R.M.; Chauhan, S.S.; Saraya, A. High levels of cell-free circulating nucleic acids in pancreatic cancer are associated with vascular encasement, metastasis and poor survival. Cancer Investig. 2015, 33, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bootcov, M.R.; Bauskin, A.R.; Valenzuela, S.M.; Moore, A.G.; Bansal, M.; He, X.Y.; Zhang, H.P.; Donnellan, M.; Mahler, S.; Pryor, K.; et al. MIC-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a divergent member of the TGF-β superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 11514–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welsh, J.B.; Sapinoso, L.M.; Kern, S.G.; Hampton, G.M.; Su, A.I.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Moskaluk, C.A.; Frierson, H.F. Analysis of gene expression identifies candidate markers and pharmacological targets in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5974–5978. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.H.; Yang, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Koo, T.H.; Shin, S.M.; Song, K.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.J.; et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 induces the invasiveness of gastric cancer cells by up-regulating the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 4648–4655. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmann, J.; Buckhaults, P.; Brown, D.A.; Zahurak, M.L.; Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Sokoll, L.J.; Chan, D.W.; Yeo, C.J.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. Serum Macrophage Inhibitory Cytokine 1 as a Marker of Pancreatic and Other Periampullary Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koopmann, J.; Rosenzweig, C.N.W.; Zhang, Z.; Canto, M.I.; Brown, D.A.; Hunter, M.; Yeo, C.; Chan, D.W.; Breit, S.N.; Goggins, M. Serum markers in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 versus CA19-9. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gold, D.V.; Lew, K.; Maliniak, R.; Hernandez, M.; Cardillo, T. Characterization of monoclonal antibody PAM4 reactive with a pancreatic cancer mucin. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 57, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, D.V.; Modrak, D.E.; Ying, Z.; Cardillo, T.M.; Sharkey, R.M.; Goldenberg, D.M. New MUC1 serum immunoassay differentiates pancreatic cancer from pancreatitis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlund, D.; Ardnor, B.; Öman, M.; Naredi, P.; Sund, M. Expression pattern and circulating levels of endostatin in patients with pancreas cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 2805–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, O.; Öhlund, D.; Lundin, C.; Öman, M.; Naredi, P.; Wang, W.; Sund, M. Combining conventional and stroma-derived tumour markers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hlund, D.; Lundin, C.; Ardnor, B.; Man, M.; Naredi, P.; Sund, M. Type IV collagen is a tumour stroma-derived biomarker for pancreas cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhivkova-Galunska, M.; Adwan, H.; Eyol, E.; Kleeff, J.; Kolb, A.; Bergmann, F.; Berger, M.R. Osteopontin but not osteonectin favors the metastatic growth of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Cancer Biol. 2010, 10, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolb, A.; Kleeff, J.; Guweidhi, A.; Esposito, I.; Giese, N.A.; Adwan, H.; Giese, T.; Büchler, M.W.; Berger, M.R.; Friess, H. Osteopontin influences the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells and is increased in neoplastic and inflammatory conditions. Cancer Biol. 2005, 4, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koopmann, J.; Fedarko, N.S.; Jain, A.; Maitra, A.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.; Rahman, A.; Hruban, R.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Goggins, M. Evaluation of osteopontin as biomarker for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poruk, K.E.; Firpo, M.A.; Scaife, C.L.; Adler, D.G.; Emerson, L.L.; Boucher, K.M.; Mulvihill, S.J. Serum osteopontin and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2013, 42, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willumsen, N.; Ali, S.M.; Leitzel, K.; Drabick, J.J.; Yee, N.; Polimera, H.V.; Nagabhairu, V.; Krecko, L.; Ali, A.; Maddukuri, A.; et al. Collagen fragments quantified in serum as measures of desmoplasia associate with survival outcome in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalf, W.; Ghaneh, P.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Palmer, D.H.; Cox, T.F.; Lamb, R.F.; Garner, E.; Campbell, F.; MacKey, J.R.; Costello, E.; et al. Pancreatic cancer hENT1 expression and survival from gemcitabine in patients from the ESPAC-3 trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borbath, I.; Verbrugghe, L.; Lai, R.; Gigot, J.F.; Humblet, Y.; Piessevaux, H.; Sempoux, C. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) expression is a potential predictive tool for response to gemcitabine in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, S.; Ansari, D.; Andersson, R. hENT1 expression is predictive of gemcitabine outcome in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8482–8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, D.B.; Harkin, D.P.; Johnston, P.G. 5-Fluorouracil: Mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; De La Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elander, N.O.; Aughton, K.; Ghaneh, P.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Palmer, D.H.; Cox, T.F.; Campbell, F.; Costello, E.; Halloran, C.M.; Mackey, J.R.; et al. Expression of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) and hENT1 predicts survival in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, E.; Petke, D.; Böger, C.; Behrens, H.M.; Warneke, V.; Ebert, M.; Röcken, C. The spatial distribution of LGR5+ cells correlates with gastric cancer progression. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, L.; Huang, Q.; Mashimo, H. Lgr5, an intestinal stem cell marker, is abnormally expressed in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dis. Esophagus 2010, 23, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, N.; Yatabe, Y.; Hara, K.; Hijioka, S.; Imaoka, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Ko, S.B.H.; Yamao, K. Cytoplasmic expression of LGR5 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuraishi, Y.; Uehara, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Watanabe, T.; Shimizu, A.; Ota, H.; Tanaka, E. Correlation of clinicopathological features and leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahr, S.; Hentze, H.; Englisch, S.; Hardt, D.; Fackelmayer, F.O.; Hesch, R.D.; Knippers, R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: Quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Shao, F.; Wu, X.; Ying, K. Value of quantitative analysis of circulating cell free DNA as a screening tool for lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2010, 69, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Fleischhacker, M.; Rabien, A. Cell-free DNA in the blood as a solid tumor biomarker-A critical appraisal of the literature. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, G.D.; Pribish, D.M.; Valone, F.H.; Memoli, V.A.; Bzik, D.J.; Yao, S.L. Soluble Normal and Mutated DNA Sequences from Single-Copy Genes in Human Blood. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1994, 3, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, P.; Chang, D.K.; Nones, K.; Johns, A.L.; Patch, A.M.; Gingras, M.C.; Miller, D.K.; Christ, A.N.; Bruxner, T.J.C.; Quinn, M.C.; et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2016, 531, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biankin, A.V.; Waddell, N.; Kassahn, K.S.; Gingras, M.C.; Muthuswamy, L.B.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.K.; Wilson, P.J.; Patch, A.M.; Wu, J.; et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 2012, 491, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, N.; Pajic, M.; Patch, A.M.; Chang, D.K.; Kassahn, K.S.; Bailey, P.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.; Nones, K.; Quek, K.; et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 518, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eser, S.; Schnieke, A.; Schneider, G.; Saur, D. Oncogenic KRAS signalling in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacona, M.B.; Ruben, G.C.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Roos, T.B.; Porter, D.M.; Sorenson, G.D. Cell-free DNA in human blood plasma: Length measurements in patients with pancreatic cancer and healthy controls. Pancreas 1998, 17, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo, P.; Cowley, C.M.; Neal, C.P.; Mistry, V.; Page, K.; Dennison, A.R.; Isherwood, J.; Hastings, R.; Luo, J.L.; Moore, D.A.; et al. Profiling tumour heterogeneity through circulating tumour DNA in patients with pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 87221–87233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, G.; Park, J.K.; Son, D.S.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Jeon, H.J.; Lee, J.; Park, W.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Park, D. Utility of targeted deep sequencing for detecting circulating tumor DNA in pancreatic cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pishvaian, M.J.; Bender, R.J.; Matrisian, L.M.; Rahib, L.; Hendifar, A.; Hoos, W.A.; Mikhail, S.; Chung, V.; Picozzi, V.; Heartwell, C.; et al. A pilot study evaluating concordance between blood-based and patient-matched tumor molecular testing within pancreatic cancer patients participating in the Know Your Tumor (KYT) initiative. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 83446–83456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riviere, P.; Fanta, P.T.; Ikeda, S.; Baumgartner, J.; Heestand, G.M.; Kurzrock, R. The mutational landscape of gastrointestinal malignancies as reflected by circulating tumor DNA. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zill, O.A.; Greene, C.; Sebisanovic, D.; Siew, L.M.; Leng, J.; Vu, M.; Hendifar, A.E.; Wang, Z.; Atreya, C.E.; Kelley, R.K.; et al. Cell-Free DNA Next-Generation Sequencing in Pancreatobiliary Carcinomas. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takai, E.; Totoki, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Morizane, C.; Nara, S.; Hama, N.; Suzuki, M.; Furukawa, E.; Kato, M.; Hayashi, H.; et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA for molecular assessment in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vietsch, E.E.; Graham, G.T.; McCutcheon, J.N.; Javaid, A.; Giaccone, G.; Marshall, J.L.; Wellstein, A. Circulating cell-free DNA mutation patterns in early and late stage colon and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Genet. 2017, 218–219, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Javed, A.A.; Thoburn, C.; Wong, F.; Tie, J.; Gibbs, P.; Schmidt, C.M.; Yip-Schneider, M.T.; Allen, P.J.; Schattner, M.; et al. Combined circulating tumor DNA and protein biomarker-based liquid biopsy for the earlier detection of pancreatic cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10202–10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Calvez-Kelm, F.; Foll, M.; Wozniak, M.B.; Delhomme, T.M.; Durand, G.; Chopard, P.; Pertesi, M.; Fabianova, E.; Adamcakova, Z.; Holcatova, I.; et al. KRAS mutations in blood circulating cell-free DNA: A pancreatic cancer case-control study. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 78827–78840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berger, A.W.; Schwerdel, D.; Costa, I.G.; Hackert, T.; Strobel, O.; Lam, S.; Barth, T.F.; Schröppel, B.; Meining, A.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. Detection of Hot-Spot Mutations in Circulating Cell-Free DNA from Patients with Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.D.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Thoburn, C.; Afsari, B.; Danilova, L.; Douville, C.; Javed, A.A.; Wong, F.; Mattox, A.; et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 2018, 359, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berger, A.W.; Schwerdel, D.; Reinacher-Schick, A.; Uhl, W.; Algul, H.; Friess, H.; Janssen, K.P.; Konig, A.; Ghadimi, M.; Gallmeier, E.; et al. A Blood-Based Multi Marker Assay Supports the Differential Diagnosis of Early-Stage Pancreatic Cancer. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; Wei, T.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Enrichment of short mutant cell-free DNA fragments enhanced detection of pancreatic cancer. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eissa, M.A.L.; Lerner, L.; Abdelfatah, E.; Shankar, N.; Canner, J.K.; Hasan, N.M.; Yaghoobi, V.; Huang, B.; Kerner, Z.; Takaesu, F.; et al. Promoter methylation of ADAMTS1 and BNC1 as potential biomarkers for early detection of pancreatic cancer in blood. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Singhania, R.; Fehringer, G.; Chakravarthy, A.; Roehrl, M.H.A.; Chadwick, D.; Zuzarte, P.C.; Borgida, A.; Wang, T.T.; Li, T.; et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature 2018, 563, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Woo, S.M.; Park, B.; Yoon, K.A.; Kim, Y.H.; Joo, J.; Lee, W.J.; Han, S.S.; Park, S.J.; Kong, S.Y. Prognostic Implications of Multiplex Detection of KRAS Mutations in Cell-Free DNA from Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strijker, M.; Soer, E.C.; de Pastena, M.; Creemers, A.; Balduzzi, A.; Beagan, J.J.; Busch, O.R.; van Delden, O.M.; Halfwerk, H.; van Hooft, J.E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA quantity is related to tumor volume and both predict survival in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjensvoll, K.; Lapin, M.; Buhl, T.; Oltedal, S.; Steen-Ottosen Berry, K.; Gilje, B.; Søreide, J.A.; Javle, M.; Nordgård, O.; Smaaland, R. Clinical relevance of circulating KRAS mutated DNA in plasma from patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earl, J.; Garcia-Nieto, S.; Martinez-Avila, J.C.; Montans, J.; Sanjuanbenito, A.; Rodríguez-Garrote, M.; Lisa, E.; Mendía, E.; Lobo, E.; Malats, N.; et al. Circulating tumor cells (Ctc) and kras mutant circulating free Dna (cfdna) detection in peripheral blood as biomarkers in patients diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hadano, N.; Murakami, Y.; Uemura, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kondo, N.; Nakagawa, N.; Sueda, T.; Hiyama, E. Prognostic value of circulating tumour DNA in patients undergoing curative resection for pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Kim, D.U.; San Lucas, F.A.; Castillo, J.; Allenson, K.; Mulu, F.C.; Stephens, B.M.; Huang, J.; Semaan, A.; Guerrero, P.A.; et al. Circulating Nucleic Acids Are Associated with Outcomes of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Luo, G.; Lu, Y.; Jin, K.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; et al. Analysis of ctDNA to predict prognosis and monitor treatment responses in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2344–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, M.; Vivaldi, C.; Rofi, E.; Vasile, E.; Miccoli, M.; Caparello, C.; D’Arienzo, P.D.; Fornaro, L.; Falcone, A.; Danesi, R. Early changes in plasma DNA levels of mutant KRAS as a sensitive marker of response to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, S.; Heinemann, V.; Ross, C.; Diehl, F.; Nagel, D.; Ormanns, S.; Liebmann, S.; Prinz-Bravin, I.; Westphalen, C.B.; Haas, M.; et al. Repeated mut KRAS ctDNA measurements represent a novel and promising tool for early response prediction and therapy monitoring in advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapin, M.; Oltedal, S.; Tjensvoll, K.; Buhl, T.; Smaaland, R.; Garresori, H.; Javle, M.; Glenjen, N.I.; Abelseth, B.K.; Gilje, B.; et al. Fragment size and level of cell-free DNA provide prognostic information in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohan, S.; Ayub, M.; Rothwell, D.G.; Gulati, S.; Kilerci, B.; Hollebecque, A.; Sun Leong, H.; Smith, N.K.; Sahoo, S.; Descamps, T.; et al. Analysis of circulating cell-free DNA identifies KRAS copy number gain and mutation as a novel prognostic marker in Pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Kitago, M.; Matsuda, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Imai, S.; Shinoda, M.; Yagi, H.; Abe, Y.; Hibi, T.; et al. KRAS mutations in cell- free DNA from preoperative and postoperative sera as a pancreatic cancer marker: A retrospective study. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perets, R.; Greenberg, O.; Shentzer, T.; Semenisty, V.; Epelbaum, R.; Bick, T.; Sarji, S.; Ben-Izhak, O.; Sabo, E.; Hershkovitz, D. Mutant KRAS Circulating Tumor DNA Is an Accurate Tool for Pancreatic Cancer Monitoring. Oncologist 2018, 23, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pietrasz, D.; Pécuchet, N.; Garlan, F.; Didelot, A.; Dubreuil, O.; Doat, S.; Imbert-Bismut, F.; Karoui, M.; Vaillant, J.C.; Taly, V.; et al. Plasma circulating tumor DNA in pancreatic cancer patients is a prognostic marker. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Su, W.; Li, G.; Ma, T.; Gao, S.; Lou, J.; Que, R.; Zheng, L.; et al. Monitoring tumor burden in response to FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy via profiling circulating cell-free DNA in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sausen, M.; Phallen, J.; Adleff, V.; Jones, S.; Leary, R.J.; Barrett, M.T.; Anagnostou, V.; Parpart-Li, S.; Murphy, D.; Li, Q.K.; et al. Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpu, Y.; Hanoun, N.; Lulka, H.; Sicard, F.; Selves, J.; Buscail, L.; Torrisani, J.; Cordelier, P. Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Philipp, A.B.; Nagel, D.; Stieber, P.; Lamerz, R.; Thalhammer, I.; Herbst, A.; Kolligs, F.T. Circulating cell-free methylated DNA and lactate dehydrogenase release in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henriksen, S.D.; Madsen, P.H.; Krarup, H.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O. DNA Hypermethylation as a Blood-Based Marker for Pancreatic Cancer: A Literature Review. Pancreas 2015, 44, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeck, J.; Niederacher, D.; An, H.; Klopocki, E.; Wiesmann, F.; Betz, B.; Galm, O.; Camara, O.; Dürst, M.; Kristiansen, G.; et al. Aberrant methylation of the Wnt antagonist SFRP1 in breast cancer is associated with unfavourable prognosis. Oncogene 2006, 25, 3479–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henriksen, S.D.; Madsen, P.H.; Larsen, A.C.; Johansen, M.B.; Pedersen, I.S.; Krarup, H.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O. Cell-free DNA promoter hypermethylation in plasma as a predictive marker for survival of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 93942–93956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Aakre, J.A.; Jiang, R.; Marks, R.S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Pankratz, V.S.; Yang, P. Methylation markers for small cell lung cancer in peripheral blood leukocyte DNA. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, K.S.; Bamlet, W.R.; Oberg, A.L.; de Andrade, M.; Matsumoto, M.E.; Tang, H.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Petersen, G.M.; Wang, L. Leukocyte DNA methylation signature differentiates pancreatic cancer patients from healthy controls. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tumas, J.; Baskirova, I.; Petrenas, T.; Norkuniene, J.; Strupas, K.; Sileikis, A. Towards a personalized approach in pancreatic cancer diagnostics through plasma amino acid analysis. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerle, J.; Kalthoff, H.; Reszka, R.; Kamlage, B.; Peter, E.; Schniewind, B.; González Maldonado, S.; Pilarsky, C.; Heidecke, C.D.; Schatz, P.; et al. Metabolic biomarker signature to differentiate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from chronic pancreatitis. Gut 2018, 67, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gangi, I.M.; Mazza, T.; Fontana, A.; Copetti, M.; Fusilli, C.; Ippolito, A.; Mattivi, F.; Latiano, A.; Andriulli, A.; Vrhovsek, U.; et al. Metabolomic profile in pancreatic cancer patients: A consensusbased approach to identify highly discriminating metabolites. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 5815–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Culp-Hill, R.; Reisz, J.A.; Lawson, P.J.; Sauaia, A.; Schulick, R.D.; Del Chiaro, M.; Nydam, T.L.; Moore, E.E.; Hansen, K.C.; et al. The metabolic time line of pancreatic cancer: Opportunities to improve early detection of adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 218, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, S.; Faitot, F.; Imperiale, A.; Cicek, A.E.; Heimburger, C.; Averous, G.; Bachellier, P.; Namer, I.J. Metabolomics approaches in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Tumor metabolism profiling predicts clinical outcome of patients. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phua, L.C.; Goh, S.; Tai, D.W.M.; Leow, W.Q.; Alkaff, S.M.F.; Chan, C.Y.; Kam, J.H.; Lim, T.K.H.; Chan, E.C.Y. Metabolomic prediction of treatment outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients receiving gemcitabine. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 2018, 81, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, E.G.; Ciborowski, M. Applications of metabolomics in cancer studies. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 965, pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeff, J.; Beckhove, P.; Esposito, I.; Herzig, S.; Huber, P.E.; Löhr, J.M.; Friess, H. Pancreatic cancer microenvironment. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatcott, C.J.; Han, H.; Von Hoff, D.D. Orchestrating the Tumor Microenvironment to Improve Survival for Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer J. 2015, 21, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mlecnik, B.; Bindea, G.; Angell, H.K.; Maby, P.; Angelova, M.; Tougeron, D.; Church, S.E.; Lafontaine, L.; Fischer, M.; Fredriksen, T.; et al. Integrative Analyses of Colorectal Cancer Show Immunoscore Is a Stronger Predictor of Patient Survival Than Microsatellite Instability. Immunity 2016, 44, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feldmann, K.; Maurer, C.; Peschke, K.; Teller, S.; Schuck, K.; Steiger, K.; Engleitner, T.; Öllinger, R.; Nomura, A.; Wirges, N.; et al. Mesenchymal plasticity regulated by Prrx1 drives aggressive pancreatic cancer biology. Gastroenterology 2020, 7, 35147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, E.; Maitra, A.; McAllister, F. Immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: More than just a gut feeling. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bazhin, A.V.; Shevchenko, I.; Umansky, V.; Werner, J.; Karakhanova, S. Two immune faces of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Possible implication for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erkan, M.; Hausmann, S.; Michalski, C.W.; Fingerle, A.A.; Dobritz, M.; Kleeff, J.; Friess, H. The role of stroma in pancreatic cancer: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandol, S.; Edderkaoui, M.; Gukovsky, I.; Lugea, A.; Gukovskaya, A. Desmoplasia of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, S44–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Masamune, A.; Kikuta, K.; Watanabe, T.; Satoh, K.; Hirota, M.; Shimosegawa, T. Hypoxia stimulates pancreatic stellate cells to induce fibrosis and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G709–G717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, M.F.B.; Mortensen, M.B.; Detlefsen, S. Key players in pancreatic cancer-stroma interaction: Cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial and inflammatory cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 2678–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, M.; Michalski, C.W.; Rieder, S.; Reiser-Erkan, C.; Abiatari, I.; Kolb, A.; Giese, N.A.; Esposito, I.; Friess, H.; Kleeff, J. The Activated Stroma Index Is a Novel and Independent Prognostic Marker in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 6, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, E.S.; Vail, P.; Balaji, U.; Ngo, H.; Botros, I.W.; Makarov, V.; Riaz, N.; Balachandran, V.; Leach, S.; Thompson, D.M.; et al. Stratification of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Combinatorial genetic, stromal, and immunologic markers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4429–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moffitt, R.A.; Marayati, R.; Flate, E.L.; Volmar, K.E.; Loeza, S.G.H.; Hoadley, K.A.; Rashid, N.U.; Williams, L.A.; Eaton, S.C.; Chung, A.H.; et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, I.; Buchholz, S.M.; Patzak, M.S.; Goetze, R.G.; Singh, S.K.; Richards, F.M.; Jodrell, D.I.; Sipos, B.; Ströbel, P.; Ellenrieder, V.; et al. SPARC dependent collagen deposition and gemcitabine delivery in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreas cancer. EBioMedicine 2019, 48, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorchs, L.; Ahmed, S.; Mayer, C.; Knauf, A.; Fernández Moro, C.; Svensson, M.; Heuchel, R.; Rangelova, E.; Bergman, P.; Kaipe, H. The vitamin D analogue calcipotriol promotes an anti-tumorigenic phenotype of human pancreatic CAFs but reduces T cell mediated immunity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, K.P.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Davidson, C.J.; Gopinathan, A.; McIntyre, D.; Honess, D.; Madhu, B.; Goldgraben, M.A.; Caldwell, M.E.; Allard, D.; et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009, 324, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rhim, A.D.; Oberstein, P.E.; Thomas, D.H.; Mirek, E.T.; Palermo, C.F.; Sastra, S.A.; Dekleva, E.N.; Saunders, T.; Becerra, C.P.; Tattersall, I.W.; et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Özdemir, B.C.; Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Carstens, J.L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, C.C.; Simpson, T.R.; Laklai, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Kahlert, C.; Novitskiy, S.V.; et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Öhlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyada, E.; Bolisetty, M.; Laise, P.; Flynn, W.F.; Courtois, E.T.; Burkhart, R.A.; Teinor, J.A.; Belleau, P.; Biffi, G.; Lucito, M.S.; et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrone, C.; Dranoff, G. Dual roles for immunity in gastrointestinal cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4045–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, G.P.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 22, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, N.; Zaitoun, A.M.; Arora, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Ilyas, M.; Lobo, D.N. The presence of tumour-associated lymphocytes confers a good prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: An immunohistochemical study of tissue microarrays. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ino, Y.; Yamazaki-Itoh, R.; Shimada, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Kosuge, T.; Kanai, Y.; Hiraoka, N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miksch, R.C.; Schoenberg, M.B.; Weniger, M.; Bösch, F.; Ormanns, S.; Mayer, B.; Werner, J.; Bazhin, A.V.; D’Haese, J.G. Prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and neutrophils on survival of patients with upfront resection of pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nomi, T.; Sho, M.; Akahori, T.; Hamada, K.; Kubo, A.; Kanehiro, H.; Nakamura, S.; Enomoto, K.; Yagita, H.; Azuma, M.; et al. Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of the programmed death-1 ligand/programmed death-1 pathway in human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 2151–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beatty, G.L.; O’Hara, M.H.; Lacey, S.F.; Torigian, D.A.; Nazimuddin, F.; Chen, F.; Kulikovskaya, I.M.; Soulen, M.C.; McGarvey, M.; Nelson, A.M.; et al. Activity of Mesothelin-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Against Pancreatic Carcinoma Metastases in a Phase 1 Trial. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Tykodi, S.S.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Hwu, W.J.; Topalian, S.L.; Hwu, P.; Drake, C.G.; Camacho, L.H.; Kauh, J.; Odunsi, K.; et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Royal, R.E.; Levy, C.; Turner, K.; Mathur, A.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.S.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Yang, J.C.; Lowy, I.; et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent ipilimumab (Anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. 2010, 33, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentjens, R.J.; Davila, M.L.; Riviere, I.; Park, J.; Wang, X.; Cowell, L.G.; Bartido, S.; Stefanski, J.; Taylor, C.; Olszewska, M.; et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 177ra38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kochenderfer, J.N.; Dudley, M.E.; Feldman, S.A.; Wilson, W.H.; Spaner, D.E.; Maric, I.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Phan, G.Q.; Hughes, M.S.; Sherry, R.M.; et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 2012, 119, 2709–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupp, S.A.; Kalos, M.; Barrett, D.; Aplenc, R.; Porter, D.L.; Rheingold, S.R.; Teachey, D.T.; Chew, A.; Hauck, B.; Wright, J.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wedén, S.; Klemp, M.; Gladhaug, I.P.; Mãller, M.; Eriksen, J.A.; Gaudernack, G.; Buanes, T. Long-term follow-up of patients with resected pancreatic cancer following vaccination against mutant K-ras. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjertsen, M.K.; Buanes, T.; Rosseland, A.R.; Bakka, A.; Gladhaug, I.; Sreide, O.; Eriksen, J.A. Intradermal ras peptide vaccination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as adjuvant: Clinical and immunological responses in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 92, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, E.M.; Hruban, R.H.; Biedrzycki, B.; Laheru, D.; Schepers, K.; Sauter, P.R.; Goemann, M.; Coleman, J.; Grochow, L.; Donehower, R.C.; et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: A phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, L.; Yeo, C.J.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Biedrzycki, B.; Kobrin, B.; Herman, J.; Sugar, E.; Piantadosi, S.; Cameron, J.L.; Solt, S.; et al. A lethally irradiated allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A phase II trial of safety, efficacy, and immune activation. Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le, D.T.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Picozzi, V.; Greten, T.F.; Crocenzi, T.; Springett, G.; Morse, M.; Zeh, H.; Cohen, D.; Fine, R.L.; et al. Safety and survival with GVAX pancreas prime and Listeria monocytogenes-expressing mesothelin (CRS-207) boost vaccines for metastatic pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groeneveldt, C.; Kinderman, P.; van den Wollenberg, D.J.M.; van den Oever, R.L.; Middelburg, J.; Mustafa, D.A.M.; Hoeben, R.C.; van der Burg, S.H.; van Hall, T.; van Montfoort, N. Preconditioning of the tumor microenvironment with oncolytic reovirus converts CD3-bispecific antibody treatment into effective immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Picardo, S.L.; Coburn, B.; Hansen, A.R. The microbiome and cancer for clinicians. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 141, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Drake, C.G.; Pardoll, D.M. Immune checkpoint blockade: A common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; Shintaku, I.P.; Taylor, E.J.M.; Robert, L.; Chmielowski, B.; Spasic, M.; Henry, G.; Ciobanu, V.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The pancreatic cancer microbiome promotes oncogenesis by induction of innate and adaptive immune suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitsuhashi, K.; Nosho, K.; Sukawa, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ito, M.; Kurihara, H.; Kanno, S.; Igarashi, H.; Naito, T.; Adachi, Y.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium species in pancreatic cancer tissues with molecular features and prognosis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7209–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, X.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Wu, J.; Peters, B.A.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Purdue, M.P.; Abnet, C.C.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.; Miller, G.; et al. Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: A population-based nested case-control study. Gut 2018, 67, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaud, D.S.; Izard, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.S.; You, D.H.; Grote, V.A.; Tjønneland, A.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; Jenab, M.; Fedirko, V.; et al. Plasma antibodies to oral bacteria and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large European prospective cohort study. Gut 2013, 62, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riquelme, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Montiel, M.; Zoltan, M.; Dong, W.; Quesada, P.; Sahin, I.; Chandra, V.; San Lucas, A.; et al. Tumor Microbiome Diversity and Composition Influence Pancreatic Cancer Outcomes. Cell 2019, 178, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, R.; Kesh, K.; Arora, N.; Di Martino, L.; McAllister, F.; Merchant, N.; Banerjee, S.; Banerjee, S. Microbial dysbiosis and polyamine metabolism as predictive markers for early detection of pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker, Serum | Reference | Sensitivity | Specificity | n of Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA 19-9 | [33] | 81 | 90 | 1040 a |

| [28] | 75.5 | 77.6 | 3497 a | |

| [17] | 79 | 82 | 2283 a | |

| [34] | 81 | 81 | 3125 a | |

| CEA | [35] | 39 | 91 | 123 |

| [28] | 39.5 | 81.3 | 3497 a | |

| [32] | 45 | 75 | 68 | |

| CA 125 | [36] | 66.8 | 83.3 | 110 |

| [35] | 57 | 78 | 123 | |

| CA 50 | [37] | 84 | 85 | 200 |

| [29] | 46.3 | 90.9 | 112 | |

| [31] | 82 | 78 | 129 | |

| CA 72-4 | [31] | 63.4 | 75.2 | 129 |

| CA 242 | [28] | 67.8 | 83 | 3497 a |

| [31] | 82 | 78 | 129 | |

| [38] | 60 | 76 | 68 |

| Year | Study Type | Stage | Patients | Marker | Measure | HR (95% CI) for Death | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Prospective cohort | Localized and LAPC | 194 | KRAS mutations | Presence of KRASmut cfDNA MAF 35% | 2.8; (1.4–5.7) * 3.46 (1.4–8.5) * | [93] |

| 2017 | Retrospective cohort | Metastatic PDAC | 188 | KRAS codon 12 and ERBB2 mutations | Presence of KRASmut/ERBB2mut cfDNA | Associated with a trend towards shorter OS | [94] |

| 2017 | Prospective cohort | Advanced PDAC | 27 | KRAS MAF kinetics | KRAS MAF stability/decrease vs. increase | mOS 6.5 vs. 11.5 months (p = 0.009) | [95] |

| 2015 | Prospective cohort | Mixed localized and advanced PDAC | 31 | KRAS codon 12 mutations | Presence of KRASmut cfDNA is associated with shorter OS | 12.2 (3.3–45.1) * | [91] |

| 2016 | Prospective cohort | Resectable PDAC | 105 | KRAS codon 12 mutations | Presence of KRASmut cfDNA | 3.2 (1.8–5.4) * | [92] |

| 2018 | Prospective cohort | Mixed localized and advanced PDAC | 106 | KRAS codon 12/13 mutations | KRAS MAF > 0.415 | 1.73 (0.95–3.14) * | [88] |

| 2018 | Prospective cohort | Advanced PDAC | 54 | KRAS mutations | KRASmut concentration | Decrease in KRASmut correlates with response | [96] |

| 2018 | Prospective cohort | Advanced PDAC | 61 | Total cfDNA | cfDNA ≤ 167 bp above median plasma level | 2.24 (1.09–4.59) * | [97] |

| 2019 | Prospective cohort | LAPC and metastatic PDAC | 55 | Copy numbers and KRAS mutations | CAN † KRAS copy number-KRASmut at baseline | 7.09 (3.19–15.78) 10.94 (3.85–31.08) 3.46 (1.76–6.77) | [98] |

| 2018 | Retrospective cohort | Resectable PDAC | 45 | KRAS codon 12 mutations | Presence of post-operative KRASmut cfDNA | 2.92 (1.11–5.62) | [99] |

| 2018 | Prospective cohort | Metastatic PDAC | 17 | KRAS mutations | Detectable vs. no detectable KRASmut cfDNA | mOS 8 v. 37.5 months (p < 0.004) | [100] |

| 2017 | Prospective cohort | Mixed localized and advanced PDAC | 104 | KRAS codon 12 mutations | Detectable vs. no detectable KRASmut cfDNA KRAS MAF tertiles | 1.99 (1.13–3.5) * mOS 18.9 vs. 7.8 vs. 4.9 months (p < 0.001) | [101] |

| 2015 | Retrospective cohort | Mixed localized and advanced PDAC | 127 | KRAS codon 12 mutations and KRAS mutations concentrations | Detectable KRASmut KRASmut cfDNA concentration > 62 ng/mL | 0.8 (0.48–1.3) †† 2.8 (1.8–4.6) | [38] |

| 2019 | Prospective cohort | Metastatic PDAC | 58 | Custom NGS panel | MAF (per 1%) Detectable mutated cfDNA | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) * 2.16 (1.21–3.85) †† | [89] |

| 2016 | Prospective cohort | Advanced PDAC | 14 | KRAS codon 12 mutations | Detectable KRASmut | 5.86 (p = 0.099) | [90] |

| 2019 | Prospective cohort | Advanced PDAC | 38 | Custom NGS panel | Pre-treatment/follow-up MAF | Not applicable | [102] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khomiak, A.; Brunner, M.; Kordes, M.; Lindblad, S.; Miksch, R.C.; Öhlund, D.; Regel, I. Recent Discoveries of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers for Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3234. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113234

Khomiak A, Brunner M, Kordes M, Lindblad S, Miksch RC, Öhlund D, Regel I. Recent Discoveries of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers for Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers. 2020; 12(11):3234. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113234

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhomiak, Andrii, Marius Brunner, Maximilian Kordes, Stina Lindblad, Rainer Christoph Miksch, Daniel Öhlund, and Ivonne Regel. 2020. "Recent Discoveries of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers for Pancreatic Cancer" Cancers 12, no. 11: 3234. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113234