Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

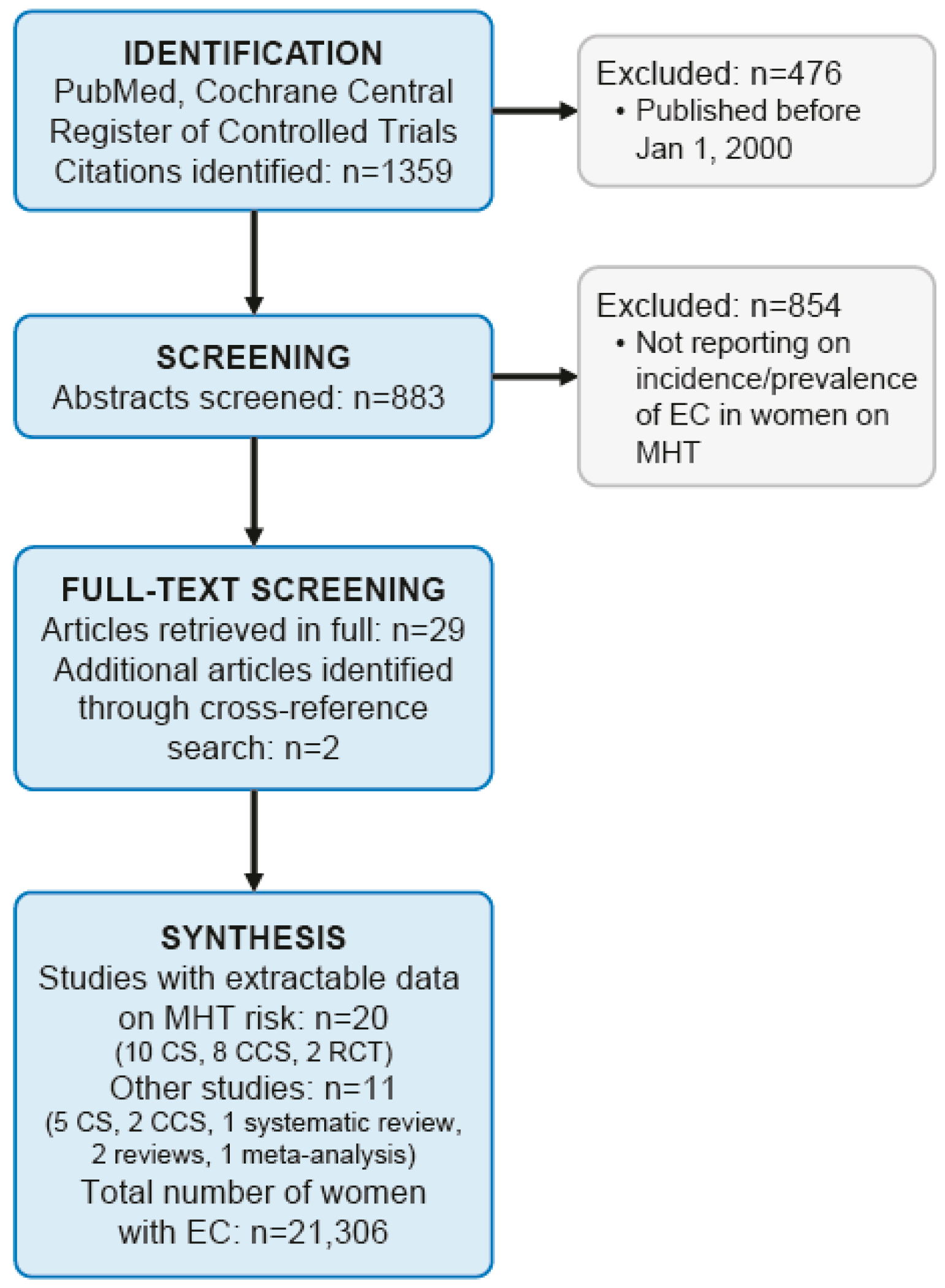

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. ccMHT with Synthetic Progestins Reduces The Risk of EC

3.2. scMHT with Synthetic Progestins May Increase The Risk of EC

3.3. ccMHT and scMHT with Progesterone or Dydrogesterone Increases The Risk of EC

3.4. Estrogen-only MHT in Women with an Intact Uterus Increases the Risk of EC

3.5. Narrative Reviews on MHT and EC Risk

3.6. Body Mass Index, MHT, and EC Risk

3.7. Influence of MHT on EC-Specific Mortality

3.8. Genetic Modulation of the Association between MHT and EC

3.9. Circulating Estrogen Levels during MHT and EC Risk

3.10. MHT and Epidemiology of EC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MHT | menopausal hormone therapy |

| ccMHT | continuous-combined MHT |

| scMHT | sequential-combined MHT |

| PCOS | polycystic ovary syndrome |

| NETA | norethisterone acetate |

| MPA | medroxyprogesterone acetate |

| PR-A | progesterone receptor alpha |

| PR-B | progesterone receptor beta |

| MAP-Ks | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| ER- α | estrogen receptor-α |

| WHI | Women’s Health Initiative |

| RR | relative risk |

| CI | confidence interval |

| BMI | body mass index |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| RER | relative survival ratio |

| SEER | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

References

- Lee, Y.C.; Lheureux, S.; Oza, A.M. Treatment strategies for endometrial cancer: Current practice and perspective. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raglan, O.; Kalliala, I.; Markozannes, G.; Cividini, S.; Gunter, M.J.; Nautiyal, J.; Gabra, H.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Tsilidis, K.K.; et al. Risk factors for endometrial cancer: An umbrella review of the literature. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der Patientinnen mit Endometriumkarzinom, Langversion 1.0. AWMF Registernummer: 032/034-OL. 2018. Available online: http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/endometriumkarzinom/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Amazit, L.; Roseau, A.; Khan, J.A.; Chauchereau, A.; Tyagi, R.K.; Loosfelt, H.; Leclerc, P.; Lombès, M.; Guiochon-Mantel, A. Ligand-dependent degradation of SRC-1 is pivotal for progesterone receptor transcriptional activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsai, M.-J.; Clark, J.H.; Schrader, W.T. Mechanisms of action of hormones that act as transcription-regulatory factors. In Williams Textbook of Endocrinology; Wilson, J., Foster, D., Kronenberg, H., Eds.; W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; pp. 55–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Anderson, G.L.; Sarto, G.E.; Haque, R.; Runowicz, C.D.; Aragaki, A.K.; Thomson, C.A.; Howard, B.V.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Chen, C.; et al. Continuous Combined Estrogen Plus Progestin and Endometrial Cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Razavi, P.; Pike, M.C.; Horn-Ross, P.L.; Templeman, C.; Bernstein, L.; Ursin, G. Long-term postmenopausal hormone therapy and endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fournier, A.; Dossus, L.; Mesrine, S.; Vilier, A.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Chabbert-Buffet, N. Risks of endometrial cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies in the E3N cohort, 1992–2008. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, G.D.; Kessler, G.; Graham, S.; Goldstein, S.R. Increased Incidence of Endometrial Cancer Following the Women’s Health Initiative: An Assessment of Risk Factors. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabert, B.; Coburn, S.B.; Falk, R.T.; Manson, J.E.; Brinton, L.A.; Gass, M.L.; Kuller, L.H.; Rohan, T.E.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Qi, L.; et al. Circulating estrogens and postmenopausal ovarian and endometrial cancer risk among current hormone users in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponholtz, T.R.; Palmer, J.R.; Rosenberg, L.A.; Hatch, E.E.; Adams-Campbell, L.L.; Wise, L.A.; Lucile, A.-C. Exogenous Hormone Use and Endometrial Cancer in U.S. Black Women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mørch, L.S.; Kjaer, S.K.; Keiding, N.; Løkkegaard, E.; Lidegaard, Ø.; Kjær, S.K. The influence of hormone therapies on type I and II endometrial cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjögren, L.L.; Mørch, L.S.; Løkkegaard, E. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review. Maturitas 2016, 91, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, A.S.; Arem, H.; Trabert, B.; Gierach, G.L.; Park, Y.K.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Brinton, L.A. Menopausal hormone therapy and mortality among endometrial cancer patients in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control 2015, 26, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brinton, L.A.; Felix, A.S. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of endometrial cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 142, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trabert, B.; Wentzensen, N.; Yang, H.P.; Sherman, M.E.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Park, Y.K.; Brinton, L.A. Is estrogen plus progestin menopausal hormone therapy safe with respect to endometrial cancer risk? Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wartko, P.; Sherman, M.E.; Yang, H.P.; Felix, A.S.; Brinton, L.A.; Trabert, B. Recent changes in endometrial cancer trends among menopausal-age U.S. women. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 37, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Razavi, P.; Lee, E.; Bernstein, L.; Berg, D.V.D.; Horn-Ross, P.L.; Ursin, G. Variations in sex hormone metabolism genes, postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of endometrial cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaakkola, S.; Lyytinen, H.K.; Dyba, T.; Ylikorkala, O.; Pukkala, E. Endometrial cancer associated with various forms of postmenopausal hormone therapy: A case control study. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, A.I.; Doherty, J.A.; Voigt, L.F.; Hill, D.A.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Rossing, M.A.; Chen, C.; Weiss, N.S. Long-term use of continuous-combined estrogen-progestin hormone therapy and risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, N.E.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Key, T.J.; Dossus, L.; Kaaks, R.; Lund, E.; Bakken, K.; Gavrilyuk, O.; Overvad, K.; Tjonneland, A.; et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of endometrial carcinoma among postmenopausal women in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, E.J.; Zwahlen, M.; Kitchener, H.C.; Egger, M.; Renehan, A. Body mass index, hormone replacement therapy, and endometrial cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orgéas, C.C.; Hall, P.; Wedrén, S.; Dickman, P.W.; Czene, K. The influence of menopausal hormone therapy on tumour characteristics and survival in endometrial cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 3064–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Patel, R.; Rodriguez, C.; Feigelson, H.S.; Bandera, E.V.; Gansler, T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E. Body mass and endometrial cancer risk by hormone replacement therapy and cancer subtype. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008, 17, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.-C.; Lacey, J.V.; Brinton, L.A.; Hartge, P.; Adams, K.; Mouw, T.; Carroll, L.; Hollenbeck, A.; Schatzkin, A.; Leitzmann, M.F. Lifetime weight history and endometrial cancer risk by type of menopausal hormone use in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doherty, J.A.; Cushing-Haugen, K.L.; Saltzman, B.S.; Voigt, L.F.; Hill, D.A.; Beresford, S.A.; Chen, C.; Weiss, N.S. Long-term use of postmenopausal estrogen and progestin hormone therapies and the risk of endometrial cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 139.e1–139.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J.J.V.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Chang, S.-C.; Mouw, T.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Schatzkin, A.; Brinton, L.A. Endometrial cancer and menopausal hormone therapy in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Cancer 2007, 109, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samsioe, G.; Boschitsch, E.; Concin, H.; De Geyter, C.; Ehrenborg, A.; Heikkinen, J.; Hobson, R.; Arguinzoniz, M.; De Palacios, P.I.; Scheurer, C.; et al. Endometrial safety, overall safety and tolerability of transdermal continuous combined hormone replacement therapy over 96 weeks: A randomized open-label study. Climacteric 2006, 9, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, B.L.; Schinnar, R.; Weber, A.L.; Bunin, G.; Berlin, J.A.; Baumgarten, M.; DeMichele, A.; Rubin, S.C.; Berlin, M.; Troxel, A.B.; et al. Case-control study of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beral, V.; Bull, D.; Reeves, G. Endometrial cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 2005, 365, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.-C.; Dietel, M.; Einenkel, J. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and endometrial morphology under consideration of the different molecular pathways in endometrial carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 122, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, K.; Alsaker, E.; Eggen, A.E.; Lund, E. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of hormone-dependent cancers in the Norwegian Women and Cancer study. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 112, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.D.; Voigt, L.F.; Beresford, S.A.; Hill, D.A.; Doherty, J.A.; Weiss, N.S. Dose of progestin in postmenopausal-combined hormone therapy and risk of endometrial cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKean-Cowdin, R.; Feigelson, H.S.; Pike, M.C.; Coetzee, G.A.; Kolonel, L.N.; Henderson, B.E. Risk of endometrial cancer and estrogen replacement therapy history by CYP17 genotype. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 848–849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.G.; Rohan, T.E.; Howe, G.R. Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer in Ontario, Canada. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.A.; Weiss, N.S.; Beresford, S.A.; Voigt, L.F.; Daling, J.R.; Stanford, J.L.; Self, S. Continuous combined hormone replacement therapy and risk of endometrial cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 183, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, H.L.; Mebane-Sims, I.; Legault, C.; Wasilauskas, C.; Johnson, S.; Merino, M.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Trabal, J.; Miller, V.T.; Barnabei, V.; et al. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. JAMA 1996, 275, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | Study Type | Number of EC Patients | Number of Controls or Cohort Size | Population Characteristics | Tumor Characteristics | Risk of EC | Subgroup Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponholtz [11] | 2018 | CS | 300 | 47,555 | US residents; Participants of the Black Women’s Health Study | Incident EC cases identified via self-report and questionnaires; confirmation by case records or cancer registries | IRR 1.55; 95% CI 0.76–3.11 for current ccMHT users vs. never users | IRR 0.63; 95% CI 0.36–1.09 for past ccMHT users vs. never users |

| Chlebowski [6] | 2016 | RCT | 161 (ccMHT: 66; placebo: 95) | 16,608 (8506 randomized to ccMHT; and 8102 to placebo) | Participants of the WHI study; postmenopausal US women with an intact uterus enrolled at 40 US clinical centers; median MHT duration: 5.6 years; median follow-up: 13 years | All histological types of EC included; all EC cases were centrally reviewed | HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.48–0.89 | HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.45–1.31 during MHT HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.40–0.88 post MHT HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.15–1.22 for mortality due to EC |

| Mørch [12] | 2016 | CS | 6202 | 914,595 | All Danish women aged 50–79 years without previous cancer or hysterectomy from 1995–2009; data acquisition by National Prescription Register and National Cancer Registry | Incident EC cases including type I and type II ECs | RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.87–1.20 for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users | RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.20–1.01 for type II ECs for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users |

| Trabert [16]; Update of [25,27] | 2013 | CS | 885 | 68,419 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.49–0.83 for ever use of ccMHT vs. never use | RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.16–0.91 for former use RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.52–0.90 for current use |

| Jaakola [19] | 2011 | CCS | 7261 (127) | 19,490 (585) | Finnish Women with EC; data acquisition via Finnish Cancer Registry; Controls 3:1 per case from the Finnish National Population Register; use of MHT assessed via Finnish Medical Reimbursement Register | All histological types of EC included | OR 0.45; 95% CI 0.27–0.73 for use <5 years of ccMHT | OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.37–0.88 for 5–10 years OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.61–1.02 for 10+ years |

| Phipps [20] Update of [26,33,36] | 2011 | CCS | 864(90) | 1343 (227) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview; population restricted to ccMHT users | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.37–0.67 for users of ccMHT vs. never users | OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.21–0.66 for long-term users (≥10 years) of ccMHT vs. never users. Protective effect of ccMHT most pronounced among obese women (BMI≥30): OR 0.19; 95% CI 0.05–0.68 |

| Allen [21] | 2010 | CS | 601 | 115,474 | Participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study from 10 European countries | All incident EC cases were included based on self-report by questionnaire; follow-up data obtained via national cancer registries or insurance databases | HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.08–0.77 for ever use of ccMHT vs. never users | - |

| Razawi [7] | 2010 | CCS | 311 (118) | 570 (223) | Public school teachers and administrators; residence in California; data acquisition via California Cancer Registry | All histological types of EC included; exclusion of: in-situ carcinomas, endometrial sarcomas and mixed Müllerian tumors | OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.55–1.35 for <5 years OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.48–1.37 for 5–9 years | OR 2.05; 95% CI 1.27–3.30 for long-term (≥10 years) of ccMHT with ≥25 d/m progestin |

| McCullough [24] | 2008 | CS | 318 | 33,436 | Participants of the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort from 21 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires and state-specific cancer registries | Incident EC cases identified via self-report and confirmed by hospital records or state-specific cancer registries and national Death Index | RR 4.41; 95% CI 2.70–7.20 for BMI ≥35 no longer significant among cc/scMHT users | Greater BMI (≥30) increased both risk of type I-EC (RR 4.22; 95% CI 3.07–5.81) and type II-EC (RR 2.87; 95% CI 1.59–5.16) |

| Chang [25] | 2007 | CS | 677 | 103,882 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 1.37; 95% CI 0.66–2.82 for obese ccMHT users vs. normal weight non MHT users | - |

| Doherty [26] Update of [33,36] | 2007 | CCS | 1038 (52) | 1453 (138) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.40–0.88 for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users | OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.45–1.3 for long-term use (≥6 years) of ccMHT vs. never users |

| Lacey [27] | 2007 | CS | 433 | 73,211 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.55–1.15 for ever users of ccMHT (≥20 days of progestin per cycle) vs. never users | Long duration of ccMHT (≥5 years) had also no effect (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.53–1.36) |

| Strom [29] | 2006 | CCS | 511 (53) | 1412 (236) | US residents in Philadelphia region from 61 clinical centers; controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | Only adenocarcinomas of the endometrium included; excluded: mixed Müllerian tumors, sarcomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, and squamous cell carcinomas | OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.48–0.99 for ever use of ccMHT | OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.33–1.81 for ever use of ccMHT vs. ever use of scMHT |

| Beral [30] | 2005 | CS | 1320 | 716,738 | UK residents participating in the Million Women Study; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases were prospectively identified; median follow-up was 3.4 years | RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.56–0.90 for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users | Beneficial effect of ccMHT was greatest among obese women |

| Bakken [32] | 2004 | CS | 75 | 27,621 | National, population-based cohort from Norway; postmenopausal women | Incident EC cases identified from questionnaires and followed-up using a national cancer registry; no restrictions on EC diagnosis | RR 0.7; 95% CI 0.4–1.4 for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users | - |

| Reed [33] Update of [36] | 2004 | CCS | 647 (38) | 1209 (123) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.7 for ever users of ccMHT (≤75 mg MPA/m) vs. never users (28 cases vs. 101 controls) | OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.4–1.9 for ever users of ccMHT (>75 mg MPA/m) vs. never users (10 cases vs. 22 controls) |

| Hill [36] | 2000 | CCS | 969 (9) | 1325 (33) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 0.6; 95% CI 0.3–1.3 for ever users of ccMHT vs. never users | OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2–1.1 for ever use of ccMHT vs. ever use of scMHT |

| Samsioe [28] | 2006 | RCT | 0 | 406 (3:1 transdermal vs. oral ccMHT) | Multicenter RCT in Sweden, Austria, Switzerland | Incident EC cases identified during 48-week follow-up | RR 0.0; no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or EC observed | - |

| Jain [35] | 2000 | CCS | 512 (15) | 513 (14) | Ontario, Canada | EC diagnosis restricted to adenocarcinoma, carcinoma, cystadenocarcinoma, or mixed Müllerian carcinoma; cases identified by Ontario Cancer Registry | OR 1.51; 95% CI 0.67–3.42 for ever use of ccMHT vs. never use | - |

| Pooled Analysis | - | CCS (n = 8), CS (n = 9), RCT (n = 2) | 11,474 (10,265 after exclusion of update studies) | 2,119,524 (1,969,172 after exclusion of update studies) | - | - | No risk increase: 8 studies Reduced risk: 9 studies | No risk increase in long-term users: 3 studies Increased risk in long-term users: 1 study |

| Author | Year | Study Type | Number of EC Patients | Number of Controls or Cohort Size | Population Characteristics | Tumor Characteristics | Risk of EC | Subgroup Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mørch [12] | 2016 | CS | 6202 | 914,595 | All Danish Women aged 50–79 years without previous cancer or hysterectomy from 1995–2009; data acquisition by National Prescription Register and National Cancer Registry | Incident EC cases including type I and type II ECs | RR 2.06; 95% CI 1.88–2.27 for ever users of scMHT vs. never users | RR 1.81; 95% CI 1.2–2.81 for type II ECs for ever users of scMHT vs. never users |

| Trabert [16]; Update of [25,27] | 2013 | CS | 885 | 68,419 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 1.23; 95% CI 0.96–1.57 for ever users of scMHT vs. never users | RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.64–1.26 for <10 years RR 1.88; 95% CI 1.36–2.60 for ≥10 years Increased risk seen only among normal-weight women (BMI < 25) |

| Jaakola [19] | 2011 | CCS | 7261 (422) | 19,490 (1126) | Finnish Women with EC; data acquisition via Finnish Cancer Registry; Controls 3:1 per case from the Finnish National Population Register; use of MHT assessed via Finnish Medical Reimbursement Register | All histological types of EC included | OR 1.38; 95% CI 1.15–1.66 for 10+ years | OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.52–0.86 for <5 years OR 1.11; 95% CI 0.87–1.41 for 5–10 years |

| Allen [21] | 2010 | CS | 601 | 115,474 | Participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study from 10 European countries | All incident EC cases were included based on self-report by questionnaire; follow-up data obtained via national cancer registries or insurance databases | HR 1.52; 95% CI 1.00–2.29 for ever users of scMHT vs. never users | - |

| Razawi [7] | 2010 | CCS | 311(50) | 570(80) | Public school teachers and administrators; residence in California; data acquisition via California Cancer Registry | All histological types of EC included; exclusion of: in-situ carcinomas, endometrial sarcomas and mixed muellerian tumors | OR 4.35; 95% CI 1.68–11.22 for long-term (≥10 years) of scMHT with <10 d/m progestin | OR 1.70; 95% CI 1.28–2.31 per 5 years of MHT with <10 d/m progestin OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.75–1.55 per 5 years of MHT with 10–24 d/m progestin |

| Chang [25] | 2007 | CS | 677 | 103,882 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 2.20; 95% CI 1.01–4.82 for obese scMHT users vs. normal weight non MHT users | - |

| Doherty [26] Update of [33] | 2007 | CCS | 1038 (109) | 1453 (166) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.2–3.5 for ever users of scMHT (10–24 d/m progestin) for ≥ 6 years vs. never users | No increased risk for scMHT (10–24 d/m progestin; <6 years) vs. never users Increased risk for any duration of scMHT with <10 d/m of progestin (OR 5.9; 95% CI 2.9–12 for ≥6 years) |

| Lacey [27] | 2007 | CS | 433 | 73,211 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.39–1.40 for ever users of scMHT users (10–14 days of progestin per cycle) vs. never users | Long duration of scMHT (≥5 years) had also no effect (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.38–1.66) |

| Strom [29] | 2006 | CCS | 511 (9) | 1412 (29) | US residents in Philadelphia region from 61 clinical centers; controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | Only adenocarcinomas of the endometrium included; excluded: mixed muellerian tumors, sarcomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, and squamous cell carcinomas | OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.39–2.05 for ever users of scMHT | - |

| Beral [30] | 2005 | CS | 1320 | 716,738 | UK residents participating in the Million Women Study; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases were prospectively identified; median follow-up was 3.4 years | RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.91–1.22 for ever users of scMHT vs. never users | Beneficial effect of scMHT was greatest among obese women |

| Reed [33] | 2004 | CCS | 647 (71) | 1209 (129) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 0.8; 95% CI 0.5–1.4 for ever users of scMHT (<100 mg MPA/m) vs. never users (19 cases vs. 53 controls) | OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.6–1.7 for ever users of scMHT (≥100 mg MPA/m) vs. never users (24 cases vs. 57 controls) OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.0–8.9 for ever users of scMHT (<70 mg MPA/m; <10 days progestin/m) vs. never users (22 cases vs. 12 controls) |

| Jain [35] | 2000 | CCS | 512 (65) | 513 (87) | Ontario, Canada | EC diagnosis restricted to adenocarcinoma, carcinoma, cystadenocarcinoma, or mixed Mullerian carcinoma; cases identified by Ontario Cancer Registry | OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.71–1.56 for ever users of scMHT vs. never users | OR 1.49; 95% CI 0.93–2.40 for ≥3 years |

| Pooled Analysis | - | CCS (n = 6), CS (n = 6) | 10,844 (9663 after exclusion of update studies) | 1,993,936 (1,843,377 after exclusion of update studies) | - | - | No risk increase: 6 studies Increased risk: 6 studies | Increased risk for long-term use and/or short duration of progestins/month: 8 studies |

| Author | Year | Study Type | Number of EC Patients | Number of Controls | Patient Population | Tumor Characteristics | Risk of EC | Subgroup Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fournier [8] | 2014 | CS | 301 | 65,630 | Postmenopausal French women insured by a National Health Insurance Fund; mainly teachers and their family members; residence in continental France; mean number of days with progesterone/month: 22.5 MP; 23.5 (dydrogesterone) | All histological types of EC included based on self-report; incident EC cases confirmed in 91% by local pathology report | HR 1.80; 95% CI 1.38–2.34 for ever use of ccMHT with MP HR 1.05; 95% CI 0.76–1.45 for ever use of ccMHT with dydrogesterone | HR 1.39; 95% CI 0.99–1.97 for≤5 years of ccMHT with MP HR 2.66; 95% CI 1.87–3.77 for>5 years of ccMHT with MP HR 1.69; 95% CI 1.06–2.70 for>5 years of ccMHT with dydrogesterone |

| Allen [21] | 2010 | CS | 601 | 115,474 | Participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study from 10 European countries | All incident EC cases were included based on self-report by questionnaire; follow-up data obtained via national cancer registries or insurance databases | HR 2.42; 95% CI 1.53–3.83 for ever use of MP vs. never use (sc/ccMHT not specified) | HR 1.23; 95% CI 0.84–1.79 for ever use of progesterone derivatives vs. never use (sc/ccMHT not specified) |

| Pooled Analysis | - | CS (n = 2) | 902 | 180,202 | - | - | Increased risk for MP: 2 studies No increased risk for dydrogesterone: 1 study | No increased risk for short-term MHT with MP: 1 study Increased risk for long-term use (>5 years) of dydrogesterone: 1 study |

| Author | Year | Study Type | Number of EC Patients | Number of Controls | Patient Population | Tumor Characteristics | Risk of EC | Subgroup Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponholtz [11] | 2018 | CS | 300 | 47,555 | US residents; Participants of the Black Women’s Health Study | Incident EC cases identified via self-report and questionnaires; confirmation by case records or cancer registries | IRR 3.78; 95% CI 1.69–8.43 for current estrogen-only MHT users vs. never users | IRR 0.87; 95% CI 0.44–1.72 for past estrogen-only MHT users vs. never users |

| Mørch [12] | 2016 | CS | 6202 | 914,595 | All Danish Women aged 50–79 years without previous cancer or hysterectomy from 1995–2009; data acquisition by National Prescription Register and National Cancer Registry | Incident EC cases including type I and type II ECs | RR 2.70; 95% CI 2.41–3.02 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | RR 1.43; 95% CI 0.85–2.41) for type II ECs for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users |

| Fournier [8] | 2014 | CS | 301 | 65,630 | Postmenopausal women insured by a National Health Insurance Fund; mainly teachers and their family members; residence in continental France; type of estrogen: estradiol (92.8%), CEE (2.2%) | All histological types of EC included based on self-report; incident EC cases confirmed in 91% by local pathology report | HR 1.80; 95% CI 1.31–2.49 for ever use of estrogen-only MHT | HR 1.81; 95% CI 1.27–2.58 for≤5 years of estrogen-only MHT HR 3.53; 95% CI 1.44–8.66 for>5 years of estrogen-only MHT |

| Trabert [16]; Update of [27] | 2013 | CS | 885 | 68,419 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.88–1.46 for ever use of estrogen-only MHT vs. never use | RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.52–1.04 for <5 years RR 1.44; 95% CI 0.68–3.03 for 5–9 years RR 3.93; 95% CI 2.62–5.89 for ≥10 years |

| Allen [21] | 2010 | CS | 601 | 115,474 | Participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study from 10 European countries | All incident EC cases were included based on self-report by questionnaire; follow-up data obtained via national cancer registries or insurance databases | HR 2.52; 95% CI 1.77–3.57 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | - |

| Razawi [7] | 2010 | CCS | 311 (104) | 570 (108) | Public school teachers and administrators; residence in California; data acquisition via California Cancer Registry | All histological types of EC included; exclusion of: in-situ carcinomas, endometrial sarcomas and mixed muellerian tumors | OR 4.46; 95% CI 2.46–8.11 for long-term (≥10 years) of estrogen-only MHT | OR 2.42; 95% CI 1.56–3.77 for <5 years OR 2.48; 95% CI 1.23–5.01 for 5–9 years |

| Doherty [26] | 2007 | CCS | 1038 (341) | 1453 (179) | US residents in 3 counties of Washington state; cases identified via registry (Cancer Surveillance System); controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | All EC cases were included except for in situ and non-epithelial cases | OR 4.6; 95% CI 3.6–5.9 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | OR 11; 95% CI 7.7–15 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT for ≥6 years vs. never users |

| Lacey [27] | 2007 | CS | 433 | 73,211 | Members of American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) from 6 US states; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases identified from state-specific cancer registries and National Death Index | RR 1.23; 95% CI 0.89–1.82 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | RR 4.07; 95% CI 2.27–7.31 for long-term users (≥10 years) of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users |

| Strom [29] | 2006 | CCS | 511 (35) | 1412 (71) | US residents in Philadelphia region from 61 clinical centers; controls recruited via random-digit-dialing telephone interview | Only adenocarcinomas of the endometrium included; excluded: mixed muellerian tumors, sarcomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, and squamous cell carcinomas | OR 1.40; 95% CI 0.86–2.26 for ever use of estrogen-only MHT of any duration | OR 3.40; 95% CI 1.40–8.30 for estrogen-only MHT for >3 years |

| Beral [30] | 2005 | CS | 1320 | 716,738 | UK residents participating in the Million Women Study; data acquisition by repeated questionnaires | Incident EC cases were prospectively identified; median follow-up was 3.4 years | RR 1.45; 95% CI 1.02–2.06 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | Adverse effect of estrogen-only MHT was greatest among non-obese women |

| Bakken [32] | 2004 | CS | 75 | 27,621 | National, population-based cohort from Norway; postmenopausal women | Incident EC cases identified from questionnaires and followed-up using a national cancer registry; no restrictions on EC diagnosis | RR 3.2; 95% CI 1.2–8.0 for ever users of estrogen-only MHT vs. never users | - |

| Jain [35] | 2000 | CCS | 512 (77) | 513 (54) | Ontario, Canada | EC diagnosis restricted to adenocarcinoma, carcinoma, cystadenocarcinoma, or mixed Mullerian carcinoma; cases identified by Ontario Cancer Registry | OR 2.23; 95% CI 1.45–3.43 for ever use of estrogen-only MHT vs. never use | OR 4.12; 95% CI 2.21–7.71 for >3 years of estrogen-only MHT vs. never use |

| Pooled Analysis | - | CCS (n = 3), CS (n = 7) | 10,674 (10,241 after exclusion of update studies) | 2,029,655 (1,952,004 after exclusion of update studies) | - | - | Increased risk: 9 studies; no increased risk: 3 studies | Increased risk with long-term use (7 studies) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tempfer, C.B.; Hilal, Z.; Kern, P.; Juhasz-Boess, I.; Rezniczek, G.A. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2020, 12, 2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082195

Tempfer CB, Hilal Z, Kern P, Juhasz-Boess I, Rezniczek GA. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2020; 12(8):2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082195

Chicago/Turabian StyleTempfer, Clemens B., Ziad Hilal, Peter Kern, Ingolf Juhasz-Boess, and Günther A. Rezniczek. 2020. "Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review" Cancers 12, no. 8: 2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082195

APA StyleTempfer, C. B., Hilal, Z., Kern, P., Juhasz-Boess, I., & Rezniczek, G. A. (2020). Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 12(8), 2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082195