Biochemical Mechanisms Associating Alcohol Use Disorders with Cancers

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Route of Alcohol through the Gastrointestinal Tract in Humans

3. Ethanol Induces Metabolic Alterations That May Cause or Facilitate Cancer Development

3.1. Oxidative and Nonoxidative Metabolism of Ethanol

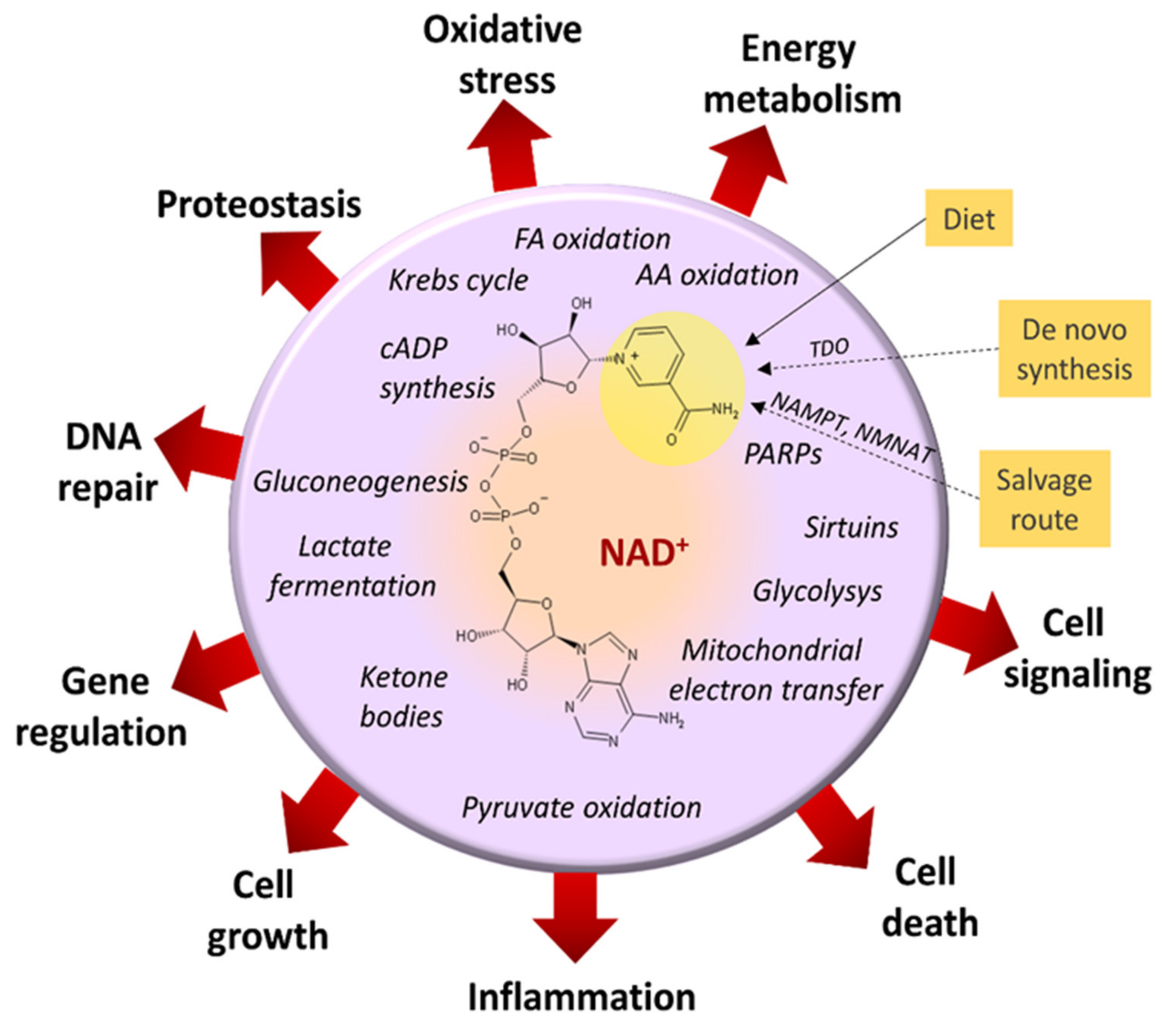

3.2. Imbalanced Proportion [Free NAD+]/[Free NADH]

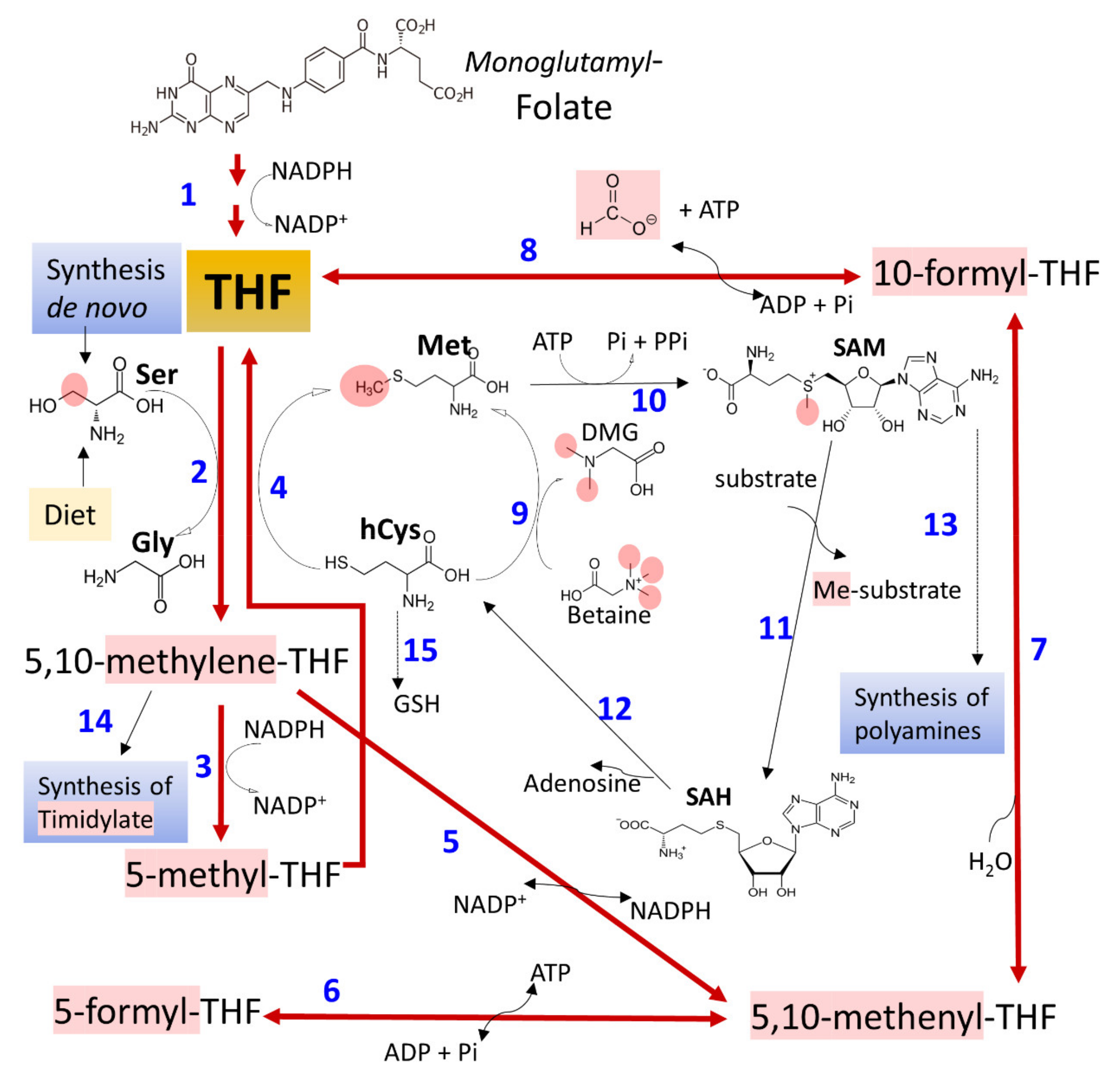

3.3. Ethanol and Metabolism of C1-Units

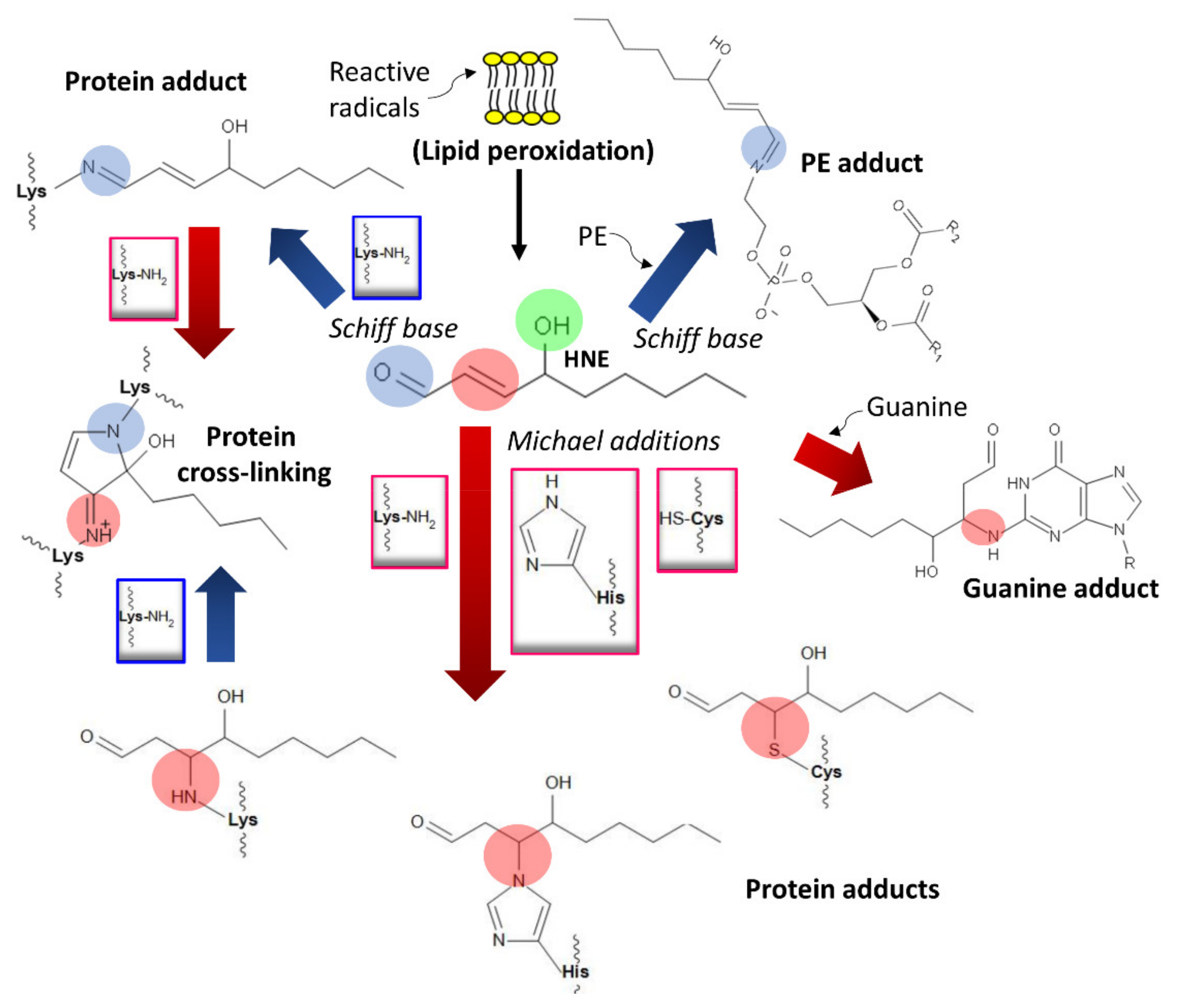

3.4. Ethanol and Oxidative Stress

3.5. Gene Variants

3.6. Ethanol and Cancer Development

4. Damage of DNA and Proteins and Epigenetic Shifts

5. Alcohol, Cancer Stem Cells Theories, and Therapeutic Strategies

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status on Alcohol and Health 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, F.D.; Covenas, R. Targeting opioid and neurokinin-1 receptors to treat alcoholism. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4321–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, F.D.; Covenas, R. Targeting NPY, CRF/UCNs, and NPS Neuropeptide systems to treat alcohol use disorder (AUD). Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 2528–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Koob, G.F.; McLellan, A.T. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pastor, R.F.; Restani, P.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Orgiu, F.; Teissedre, P.L.; Stockley, C.; Ruf, J.C.; Quini, C.I.; Garcia Tejedor, N.; Gargantini, R.; et al. Resveratrol, human health and winemaking perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodda, L.N.; Beyer, J.; Gerostamoulos, D.; Drummer, O.H. Alcohol congener analysis and the source of alcohol: A review. Forensic. Sci. Med. Pathol. 2013, 9, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Walch, S.G.; Rehm, J. Exaggeration of health risk of congener alcohols in unrecorded alcohol: Does this mislead alcohol policy efforts? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 107, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishehsari, F.; Magno, E.; Swanson, G.; Desai, V.; Voigt, R.M.; Forsyth, C.B.; Keshavarzian, A. Alcohol, and gut-derived inflammation. Alcohol. Res. 2017, 38, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Marttila, E.; Rusanen, P.; Uittamo, J.; Salaspuro, M.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Salo, T. Expression of p53 is associated with microbial acetaldehyde production in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 131, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Verma, M.; Panda, M. Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engen, P.A.; Green, S.J.; Voigt, R.M.; Forsyth, C.B.; Keshavarzian, A. The gastrointestinal microbiome: Alcohol effects on the composition of intestinal microbiota. Alcohol Res. 2015, 37, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neuzillet, C.; Marchais, M.; Vacher, S.; Hilmi, M.; Schnitzler, A.; Meseure, D.; Leclere, R.; Lecerf, C.; Dubot, C.; Jeannot, E.; et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum and association with immune-related gene expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganly, I.; Yang, L.; Giese, R.A.; Hao, Y.; Nossa, C.W.; Morris, L.G.T.; Rosenthal, M.; Migliacci, J.; Kelly, D.; Tseng, W.; et al. Periodontal pathogens are a risk factor of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, independent of tobacco and alcohol and human papillomavirus. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, K.; Baba, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Mima, K.; Miyake, K.; Nakamura, K.; Sawayama, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; et al. Human microbiome Fusobacterium nucleatum in esophageal cancer tissue is associated with prognosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 5574–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashemi Goradel, N.; Heidarzadeh, S.; Jahangiri, S.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K.; Khanlarkhani, N.; Negahdari, B. Fusobacterium nucleatum, and colorectal cancer: A mechanistic overview. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2337–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.T.; Choi, S.; Lee, H.; Kwon, S.S.; Byun, J.H.; Kim, Y.A.; Rhee, K.J.; Choi, J.R.; Kim, T.I.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in biopsied tissues from colorectal cancer patients and alcohol consumption in Korea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, L.; Alon-Maimon, T.; Sol, A.; Nejman, D.; Shhadeh, A.; Fainsod-Levi, T.; Yajuk, O.; Isaacson, B.; Abed, J.; Maalouf, N.; et al. Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, K.; Chiodini, P.; Colao, A.; Lenzi, A.; Giugliano, D. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Botteri, E.; Tramacere, I.; Islami, F.; Fedirko, V.; Scotti, L.; Jenab, M.; Turati, F.; Pasquali, E.; et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nguyen, N.; Colditz, G.A. Links between alcohol consumption and breast cancer: A look at the evidence. Womens Health. 2015, 11, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orywal, K. Szmitkowski, M. Alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase in malignant neoplasms. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 17, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratna, A.; Mandrekar, P. Alcohol and cancer: Mechanisms and therapies. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boffetta, P.; Hashibe, M. Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, F.; Lee, Y.A.; Hashibe, M.; Boffetta, P.; Conway, D.I.; Ferraroni, M.; La Vecchia, C.; Edefonti, V.; INHANCE. Consortium investigators Lessons learned from the INHANCE consortium: An overview of recent results on head and neck cancer. Oral Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Credico, G.; Polesel, J.; Dal Maso, L.; Pauli, F.; Torelli, N.; Luce, D.; Radoi, L.; Matsuo, K.; Serraino, D.; Brennan, P.; et al. Alcohol drinking and head and neck cancer risk: The joint effect of intensity and duration. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Fountzilas, E.; Nikanjam, M.; Kurzrock, R. Review of precision cancer medicine: Evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederbaum, A. Alcohol metabolism. Clin. Liv. Dis. 2012, 16, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wall, T.L.; Schoedel, K.; Ring, H.Z.; Luczak, S.E.; Katsuyoshi, D.M.; Tyndale, R.F. Differences in pharmacogenetics of nicotine and alcohol metabolism: Review and recommendations for future research. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007, 9, S459–S474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alling, C.; Gustavsson, L.; Mansson, J.E.; Benthin, G.; Anggard, E. Phosphatidylethanol formation in rat organs after ethanol treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1984, 793, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, C.J. Acetaldehyde metabolism in vivo during ethanol oxidation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1977, 85A, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guengerich, F.; Avadhani, N.G. Roles of Cytochrome P450 in Metabolism of Ethanol and Carcinogens. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1032, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, L.; Alling, C. Formation of phosphatidyl ethanol in rat brain by phospholipase D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 142, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, C.; Xie, H.; Zimmermann, R. Nonoxidative ethanol metabolism in humans-from biomarkers to bioactive lipids. IUBMB Life 2016, 68, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.S.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Zhang, Y.; Hund, D.K.; Maier, S.F.; Rice, K.C.; Watkins, L.R. Glucuronic acid and the ethanol metabolite ethyl-glucuronide cause toll-like receptor 4 activation and enhanced pain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 30, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liscovitch, M. Phosphatidylethanol biosynthesis in ethanol-exposed NG108-15 neuroblastoma X glioma hybrid cells. Evidence for activation of a phospholipase D phosphatidyl transferase activity by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, T.; Madden, L.J.; Winter, J.S.; Smith, J.L.; de Jersey, J. Fatty acid ethyl ester synthesis by human liver microsomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1299, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, T. Okuda, H. Fatty acid ethyl ester synthase in rat adipose tissue and its relationship to carboxylesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 23489–23494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, T. Okuda, H. The synthesis of fatty acid ethyl ester by carboxyl ester lipase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 224, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsham, N.E. Sherwood, R.A. Ethyl glucuronide. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 49, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, D.F. Matschinsky, F.M. Ethanol metabolism: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 140, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, R.S.; Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelner, I.; Matlow, J.N.; Natekar, A.; Koren, G. Synthesis of fatty acid ethyl esters in mammalian tissues after ethanol exposure: A systematic review of the literature. Drug Metab. Rev. 2013, 45, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimatkin, S.M.; Pronko, S.P.; Vasiliou, V.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Deitrich, R.A. Enzymatic mechanisms of ethanol oxidation in the brain. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 30, 1500–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianingtyas, H.; Wright, P.C. Alcohol dehydrogenases from thermophilic and hyperthermophilic archaea and bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-López, C.; Julián-Sánchez, A.; Riveros-Rosas, H. Diversity and evolutionary analysis of iron-containing (Type-III) alcohol dehydrogenases in eukaryotes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edenberg, H.J.; McClintick, J.N. Alcohol dehydrogenases, aldehyde dehydrogenases, and alcohol use disorders: A critical review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 2281–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, D.W.; Liangpunsakul, S. Acetaldehyde generating enzyme systems: Roles of alcohol dehydrogenase, CYP2E1 and catalase, and speculations on the role of other enzymes and processes. Novartis Found. Symp. 2007, 285, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshino, N.; Oshino, R.; Chance, B. The characteristics of the "peroxidatic" reaction of catalase in ethanol oxidation. Biochem. J. 1973, 131, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieber, C.S.; DeCarli, L.M. Ethanol oxidation by hepatic microsomes: Adaptive increase after ethanol feeding. Science 1968, 162, 917–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Han, K.; Shaik, S. A new mechanism for ethanol oxidation mediated by cytochrome P450 2E1: Bulk polarity of the active site makes a difference. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P450 2E1 and its roles in disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 322, 109056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, H.K. The role of cytochrome P4502E1 in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease and carcinogenesis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 316, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-Parikh, L.C.; Guengerich, F.P. Kinetics of cytochrome P450 2E1-catalyzed oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid via acetaldehyde. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23833–23840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Russell, R.M.; Seitz, H.K.; Wang, X.D. Ethanol enhances retinoic acid metabolism into polar metabolites in rat liver via induction of cytochrome P4502E. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I. Oxygen radicals from acetaldehyde. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1989, 7, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Ferreira, J.C.; Gross, E.R.; Mochly-Rosen, D. Targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 2: New therapeutic opportunities. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kimura, M.; Yokoyama, A.; Higuchi, S. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaspuro, M. Key role of local acetaldehyde in upper GI tract carcinogenesis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 31, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ito, A.; Jamal, M.; Ameno, K.; Tanaka, N.; Takakura, A.; Kawamoto, T.; Kitagawa, K.; Nakayama, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Miki, T.; et al. Acetaldehyde administration induces salsolinol formation in vivo in the dorsal striatum of Aldh2-knockout and C57BL/6N mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 685, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanpen, S.; Govitrapong, P.; Shavali, S.; Sangchot, P.; Ebadi, M. Salsolinol, a dopamine-derived tetrahydroisoquinoline, induces cell death by causing oxidative stress in dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells, and the said effect is attenuated by metallothionein. Brain Res. 2004, 1005, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, H.M.; Gardner, A.M.; Gross, E.R. Aldehyde-induced DNA, and protein adducts as biomarker tools for alcohol use disorder. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi-Yokoyama, H.; Yokoyama, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Imaeda, H.; Hibi, T. Acetaldehyde inhibits the formation of retinoic acid from retinal in the rat esophagus. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 41, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabtai, Y.; Bendelac, L.; Jubran, H.; Hirschberg, J.; Fainsod, A. Acetaldehyde inhibits retinoic acid biosynthesis to mediate alcohol teratogenicity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, P.J.; Theruvathu, J.A. DNA adducts from acetaldehyde: Implications for alcohol-related carcinogenesis. Alcohol 2005, 35, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Stokowski, R.P.; Kershenobich, D.; Ballinger, D.G.; Hinds, D.A. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.K.; Yates, E.; Lilly, K.; Dhanda, A.D. Oxidative stress in alcohol-related liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2020, 12, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hande, V.; Teo, K.; Srikanth, P.; Wong, J.S.M.; Sethu, S.; Martinez-Lopez, W.; Hande, M.P. Investigations on the new mechanism of action for acetaldehyde-induced clastogenic effects in human lung fibroblasts. Mutat. Res. 2021, 861–862, 503303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsufuji, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Mitsunaga, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Nakagawa, T. Novel physiological roles for glutathione in sequestering acetaldehyde to confer acetaldehyde tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Hou, J.; Guo, H.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, D.; Tang, R. The synergistic effects of waterborne microcystin-LR and nitrite on hepatic pathological damage, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant responses of male zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anni, H.; Pristatsky, P.; Israel, Y. Binding of acetaldehyde to a glutathione metabolite: Mass spectrometric characterization of an acetaldehyde-cysteinylglycine conjugate. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 27, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kera, Y.; Komura, S.; Kiriyama, T.; Inoue, K. Effects of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor and reduced glutathione on renal acetaldehyde levels in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34, 3781–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Wang, Y.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Glutathione and Transsulfuration in Alcohol-Associated Tissue Injury and Carcinogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1032, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Manna, S.K.; Golla, S.; Krausz, K.W.; Cai, Y.; Garcia-Milian, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Chakraborty, J.; Chatterjee, R.; Thompson, D.C.; et al. Glutathione deficiency-elicited reprogramming of hepatic metabolism protects against alcohol-induced steatosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. 2020. Available online: http://www.iarc.who.int/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Murata, M.; Midorikawa, K.; Kawanishi, S. Oxidative DNA damage and mammary cell proliferation by alcohol-derived salsolinol. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, U.J.; Hoerner, M.; Lasker, J.M.; Lieber, C.S. Formation of acetaldehyde adducts with ethanol-inducible P450IIE1 in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 154, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, W.C. Acetaldehyde adducts of phospholipids. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1982, 6, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Ito, H.; Matsui, H.; Hyodo, I. Acetaldehyde is an oxidative stressor for gastric epithelial cells. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2014, 55, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuma, D.J.; Hoffman, T.; Sorrell, M.F. The chemistry of acetaldehyde-protein adducts. Alcohol Alcohol. Suppl. 1991, 1, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, T.; Zhao, Y. Acetaldehyde induces phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 and mitochondrial dysfunction via elevating intracellular ROS and Ca(2+) levels. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, W.C. Formation of Schiff base adduct between acetaldehyde and rat liver microsomal phosphatidylethanolamine. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1984, 8, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.L.; Paull, P.; Haber, P.S.; Chitty, K.; Seth, D. Evaluation of a novel method for the analysis of alcohol biomarkers: Ethyl glucuronide, ethyl sulfate, and phosphatidyl ethanol. Alcohol 2018, 67, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, C.; Rodriguez, F.D.; Simonsson, P.; Alling, C.; Gustavsson, L. Phosphatidylethanol affects inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate levels in NG108-15 neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid cells. J. Neurochem. 1993, 60, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannequin, J.; Delaunay, N.; Darido, C.; Maurice, T.; Crespy, P.; Frohman, M.A.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K.; Joubert, D.; Bourgaux, J.F.; et al. Phosphatidylethanol accumulation promotes intestinal hyperplasia by inducing ZONAB-mediated cell density increase in response to chronic ethanol exposure. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007, 5, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laposata, E.A.; Lange, L.G. Presence of nonoxidative ethanol metabolism in human organs commonly damaged by ethanol abuse. Science 1986, 231, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor, M.R.; Bell, I.C., Jr. Synthesis of fatty acid esters of short-chain alcohols by an acyltransferase in rat liver microsomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1973, 306, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckemeier, M.E.; Bora, P.S. Fatty acid ethyl esters: Potentially toxic products of myocardial ethanol metabolism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998, 30, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.B.; Alquier, T.; Carling, D.; Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase: Ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell. Metab. 2005, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, M.P.; Bhopale, K.K.; Caracheo, A.A.; Amer, S.M.; Khan, S.; Kaphalia, L.; Loganathan, G.; Balamurugan, A.N.; Kaphalia, B.S. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase attenuates ethanol-induced ER/oxidative stress and lipid phenotype in human pancreatic acinar cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, A.; Miners, J.O.; Mackenzie, P.I. The UDP-glucuronosyltransferases: Their role in drug metabolism and detoxification. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbs, Z.E.; Rohn-Glowacki, K.J.; Crittenden, F.; Guidry, A.L.; Falany, C.N. Structural plasticity in the human cytosolic sulfotransferase dimer and its role in substrate selectivity and catalysis. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 30, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Fu, X.; Reisz, J.A.; Stone, M.; Kleinman, S.; Zimring, J.C.; Busch, M. Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III (REDS III) Ethyl glucuronide, a marker of alcohol consumption, correlates with metabolic markers of oxidant stress but not with hemolysis in stored red blood cells from healthy blood donors. Transfusion 2020, 60, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Freni, F.; Carelli, C.; Moretti, M.; Morini, L. Ethyl glucuronide hair testing: A review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 300, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrovito, R.; Strathmann, F.G. Distributions of alcohol use biomarkers including ethanol, phosphatidyl ethanol, ethyl glucuronide, and ethyl sulfate in clinical and forensic testing. Clin. Biochem. 2020, 82, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.W.; Loro, E.; Liu, L.; Davila, A., Jr.; Chellappa, K.; Silverman, I.M.; Quinn, W.J.; Gosai, S.J.; Tichy, E.D.; Davis, J.G.; et al. Loss of NAD Homeostasis Leads to Progressive and Reversible Degeneration of Skeletal Muscle. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thapa, M.; Dallmann, G. Role of coenzymes in cancer metabolism. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 98, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Cantó, C.; Wanders, R.J.; Auwerx, J. The secret life of NAD+: An old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krebs, H.A.; Freedland, R.A.; Hems, R.; Stubbs, M. Inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis by ethanol. Biochem. J. 1969, 112, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morozova, T.V.; Mackay, T.F.; Anholt, R.R. Genetics and genomics of alcohol sensitivity. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tomaselli, D.; Steegborn, C.; Mai, A.; Rotili, D. Sirt4: A multifaceted enzyme at the crossroads of mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, R.B.; Bao, J.; Deng, C.X. Emerging roles of SIRT1 in fatty liver diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Horvath, B.; Rajesh, M.; Varga, Z.V.; Gariani, K.; Ryu, D.; Cao, Z.; Holovac, E.; Park, O.; Zhou, Z.; et al. PARP inhibition protects against alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, I.; He, Y.Y. Targeting the AMP-activated protein kinase for cancer prevention and therapy. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of NAD-boosting molecules: The in vivo evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, R.; Schmidt, M.S.; Cain, O.; Gunson, B.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolome is functionally depressed in patients undergoing liver transplantation for alcohol-related liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroud-Gerbetant, J.; Joffraud, M.; Giner, M.P.; Cercillieux, A.; Bartova, S.; Makarov, M.V.; Zapata-Pérez, R.; Sánchez-García, J.L.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Migaud, M.E.; et al. A reduced form of nicotinamide riboside defines a new path for NAD(+) biosynthesis and acts as an orally bioavailable NAD(+) precursor. Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.E.; Sharif, T.; Martell, E.; Dai, C.; Kim, Y.; Lee, P.W.; Gujar, S.A. NAD(+) salvage pathway in cancer metabolism and therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell. Metab. 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Newman, A.C.; Maddocks, O.D.K. One-carbon metabolism in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soda, K. Polyamine Metabolism and Gene Methylation in Conjunction with One-Carbon Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mentch, S.J.; Locasale, J.W. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics: Understanding the specificity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1363, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reina-Campos, M.; Diaz-Meco, M.T.; Moscat, J. The complexity of the serine glycine one-carbon pathway in cancer. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201907022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhne, A.S.; Hou, Z.; Gangjee, A.; Matherly, L.H. Therapeutic Targeting of Mitochondrial One-Carbon Metabolism in Cancer. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 2020, 19, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locasale, J.W. Serine, glycine, and one-carbon units: Cancer metabolism in full circle. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013, 13, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asai, A.; Konno, M.; Koseki, J.; Taniguchi, M.; Vecchione, A.; Ishii, H. One-carbon metabolism for cancer diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.M.; Ye, J. Reprogramming of serine, glycine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Vousden, K.H. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016, 16, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.B.; Choi, S.W. Effects of alcohol on folate metabolism: Implications for carcinogenesis. Alcohol 2005, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsted, C.H.; Robles, E.A.; Mezey, E. Decreased jejunal uptake of labeled folic acid (3 H-PGA) in alcoholic patients: Roles of alcohol and nutrition. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsted, C.H.; Villanueva, J.A.; Devlin, A.M.; Niemelä, O.; Parkkila, S.; Garrow, T.A.; Wallock, L.M.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Melnyk, S.; James, S.J. Folate deficiency disturbs hepatic methionine metabolism and promotes liver injury in the ethanol-fed micropig. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10072–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Russell, R.M.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Wilson, P.D.; Iber, F.L.; Oaks, E.B.; Giovetti, A.C.; Otradovec, C.L.; Karwoski, P.A.; Press, A.W. Increased urinary excretion and prolonged turnover time of folic acid during ethanol ingestion. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 38, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, S.; Jayatilleke, E.; Herbert, V.; Colman, N. Cleavage of folates during ethanol metabolism. Role of acetaldehyde/xanthine oxidase-generated superoxide. Biochem. J. 1989, 257, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radziejewska, A.; Chmurzynska, A. Folate and choline absorption and uptake: Their role in fetal development. Biochimie 2019, 158, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waly, M.I.; Kharbanda, K.K.; Deth, R.C. Ethanol lowers glutathione in rat liver and brain and inhibits methionine synthase in a cobalamin-dependent manner. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varela-Rey, M.; Woodhoo, A.; Martinez-Chantar, M.L.; Mato, J.M.; Lu, S.C. Alcohol, DNA methylation, and cancer. Alcohol Res. 2013, 35, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hidiroglou, N.; Camilo, M.E.; Beckenhauer, H.C.; Tuma, D.J.; Barak, A.J.; Nixon, P.F.; Selhub, J. Effect of chronic alcohol ingestion on hepatic folate distribution in the rat. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 47, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimmer, E.E. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: Biochemical characterization and medical significance. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2574–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, J.; Zhang, H.; Pandey, S.C.; Guidotti, A. Chronic alcohol exposure differentially alters one-carbon metabolism in rat liver and brain. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzilli, K.M.; McClain, K.M.; Lipworth, L.; Playdon, M.C.; Sampson, J.N.; Clish, C.B.; Gerszten, R.E.; Freedman, N.D.; Moore, S.C. Identification of 102 Correlations between Serum Metabolites and Habitual Diet in a Metabolomics Study of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Trial. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Jahanzaib Anwar, M.; Usman, A.; Keshavarzian, A.; Bishehsari, F. Colorectal Cancer and Alcohol Consumption-Populations to Molecules. Cancers 2018, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, J.; Krupenko, S.A. Folate pathways mediating the effects of ethanol in tumorigenesis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 324, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.P.; Aladelokun, O.; Kadaveru, K.; Rosenberg, D.W. Methyl Donor Deficiency Blocks Colorectal Cancer Development by Affecting Key Metabolic Pathways. Cancer. Prev. Res. 2020, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, M.; Feo, F.; Pascale, R.M. Pleiotropic effects of methionine adenosyltransferases deregulation as determinants of liver cancer progression and prognosis. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamat, P.K.; Mallonee, C.J.; George, A.K.; Tyagi, S.C.; Tyagi, N. Homocysteine, Alcoholism, and Its Potential Epigenetic Mechanism. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 2474–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.A.; Stern, S.J.; Moretti, M.; Matok, I.; Sarkar, M.; Nickel, C.; Koren, G. Folate intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. Epidemiol. 2011, 35, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian. J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M.B. ROS as signaling molecules: Mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Bermejo, R.; Romo-González, M.; Pérez-Fernández, A.; Ijurko, C.; Hernández-Hernández, Á. Reactive oxygen species in haematopoiesis: Leukaemic cells take a walk on the wild side. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals, and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, F.C. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: Concepts and controversies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.S.; Dighe, P.A.; Mezera, V.; Monternier, P.A.; Brand, M.D. Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from specific mitochondrial sites under different bioenergetic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16804–16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Espey, M.G.; Miranda, K.M.; Thomas, D.D.; Xavier, S.; Citrin, D.; Vitek, M.P.; Wink, D.A. A chemical perspective on the interplay between NO, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen oxide species. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 962, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Radi, R. Peroxynitrite: Biochemistry, pathophysiology, and development of therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.K.; Mueller, S. Alcohol and cancer: An overview with special emphasis on the role of acetaldehyde and cytochrome P450 2eadv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 815, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhart, K.; Bartsch, H.; Seitz, H.K. The role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytochrome P-450 2E1 in the generation of carcinogenic etheno-DNA adducts. Redox Biol. 2014, 3, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haorah, J.; Ramirez, S.H.; Floreani, N.; Gorantla, S.; Morsey, B.; Persidsky, Y. Mechanism of alcohol-induced oxidative stress and neuronal injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alikunju, S.; Abdul Muneer, P.M.; Zhang, Y.; Szlachetka, A.M.; Haorah, J. The inflammatory footprints of alcohol-induced oxidative damage in neurovascular components. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, S129–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reddy, V.D.; Padmavathi, P.; Bulle, S.; Hebbani, A.V.; Marthadu, S.B.; Venugopalacharyulu, N.C.; Maturu, P.; Varadacharyulu, N.C. Association between alcohol-induced oxidative stress and membrane properties in synaptosomes: A protective role of vitamin E. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2017, 63, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, H.; Xia, H. Theaflavins attenuate ethanol-induced oxidative stress and cell apoptosis in gastric mucosa epithelial cells via downregulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3791–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, D.R. Alcohol, iron-associated oxidative stress, and cancer. Alcohol 2005, 35, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.G.; Zhu, J.H.; Cheng, W.H.; Bao, Y.; Ho, Y.S.; Reddi, A.R.; Holmgren, A.; Arnér, E.S. Paradoxical Roles of Antioxidant Enzymes: Basic Mechanisms and Health Implications. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 307–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, K. Jakob, U. The role of thiols in antioxidant systems. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 14–27, pii:S0891-5849(18)32542-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurban, S.; Mehmetoğlu, I. The effect of alcohol on total antioxidant activity and nitric oxide levels in the sera and brains of rats. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 38, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Haorah, J.; Floreani, N.A.; Knipe, B.; Persidsky, Y. Stabilization of superoxide dismutase by acetyl-l-carnitine in human brain endothelium during alcohol exposure: Novel protective approach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Na, H.K.; Lee, J.Y. Molecular basis of alcohol-related gastric and colon cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sobhanimonfared, F.; Bamdad, T.; Roohvand, F. Cross talk between alcohol-induced oxidative stress and HCV replication. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooprai, H.K.; Pratt, O.E.; Shaw, G.K.; Thomson, A.D. Superoxide dismutase in the erythrocytes of acute alcoholics during detoxification. Alcohol 1989, 24, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanska, J.; Todorova, B.; Labudovic, D.; Korneti, P.G. Erythrocyte antioxidant enzymes in patients with alcohol dependence syndrome. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2005, 106, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatowicz, E.; Woźniak, A.; Kulza, M.; Seńczuk-Przybyłowska, M.; Cimino, F.; Piekoszewski, W.; Chuchracki, M.; Florek, E. Exposure to alcohol and tobacco smoke causes oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopal, T.; Kumar, N.; Perriotte-Olson, C.; Casey, C.A.; Donohue, T.M., Jr.; Harris, E.N.; Talmon, G.; Kabanov, A.V.; Saraswathi, V. Nanoformulated SOD1 ameliorates the combined NASH and alcohol-associated liver disease partly via regulating CYP2E1 expression in adipose tissue and liver. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020, 318, G428–G438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolota, A.; Glabska, D.; Oczkowski, M.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Influence of Alcohol Consumption on Body Mass Gain and Liver Antioxidant Defense in Adolescent Growing Male Rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 10–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cernigliaro, C.; D’Anneo, A.; Carlisi, D.; Giuliano, M.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Barone, R.; Longhitano, L.; Cappello, F.; Emanuele, S.; Distefano, A.; et al. Ethanol-mediated stress promotes autophagic survival and aggressiveness of colon cancer cells via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Cancers 2019, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teschke, R. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Alcohol metabolism, cascade of molecular mechanisms, cellular targets, and clinical aspects. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickson, P.A.; James, M.R.; Heath, A.C.; Montgomery, G.W.; Martin, N.G.; Whitfield, J.B.; Birley, A.J. Effects of variation at the ALDH2 locus on alcohol metabolism, sensitivity, consumption, and dependence in Europeans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 30, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczak, S.E.; Pandika, D.; Shea, S.H.; Eng, M.Y.; Liang, T.; Wall, T.L. ALDH2 and ADH1B interactions in retrospective reports of low-dose reactions and initial sensitivity to alcohol in Asian American college students. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuckit, M.A. A Critical Review of Methods and Results in the Search for Genetic Contributors to Alcohol Sensitivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.M. Variability in the effect of alcohol on alcohol metabolizing enzymes may determine relative sensitivity to alcohols: A new hypothesis. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1986, 28, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Tehard, B.; Mallet, Y.; Gerber, M.; Norat, T.; Hercberg, S.; Latino-Martel, P. Alcohol and genetic polymorphisms: Effect on risk of alcohol-related cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, C.L.; Liang, T.; Gizer, I.R. ADH and ALDH polymorphisms and alcohol dependence in Mexican and Native Americans. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2012, 38, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaviria-Calle, M.; Duque-Jaramillo, A.; Aranzazu, M.; Di Filippo, D.; Montoya, M.; Roldán, I.; Palacio, N.; Jaramillo, S.; Restrepo, J.C.; Hoyos, S.; et al. Polymorphisms in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1) and cytochrome p450 2E1 (CYP2E1) genes in patients with cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomedica 2018, 38, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jelski, W.; Szmitkowski, M. Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in the cancer diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2008, 395, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Shin, A.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, J. Effects of interactions between common genetic variants and alcohol consumption on colorectal cancer risk. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 6391–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svensson, T.; Yamaji, T.; Budhathoki, S.; Hidaka, A.; Iwasaki, M.; Sawada, N.; Inoue, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Shimazu, T.; Tsugane, S. Alcohol consumption, genetic variants in the alcohol- and folate metabolic pathways and colorectal cancer risk: The JPHC Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wall, T.L.; Luczak, S.E.; Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S. Biology, Genetics, and Environment: Underlying Factors Influencing Alcohol Metabolism. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Available online: http://www.genenames.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Ashmarin, I.P.; Danilova, R.A.; Obukhova, M.F.; Moskvitina, T.A.; Prosorovsky, V.N. Main ethanol metabolizing alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH I and ADH IV): Biochemical functions and the physiological manifestation. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edenberg, H.J. The genetics of alcohol metabolism: Role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase variants. Alcohol Res. Health 2007, 30, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Polimanti, R.; Gelernter, J. ADH1B: From alcoholism, natural selection, and cancer to the human phenome. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2018, 177, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, B.; Brocker, C.; Thompson, D.C.; Black, W.; Vasiliou, K.; Nebert, D.W.; Vasiliou, V. Update on the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH) superfamily. Hum. Genom. 2011, 5, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harada, S.; Agarwal, D.P.; Goedde, H.W. Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as cause of facial flushing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet 1981, 2, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, A.; Yasunami, M.; Yoshida, A. Genotype of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase loci in Japanese alcohol flushers and nonflushers. Hum. Genet. 1989, 82, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L. Association between ALDH2 rs671 G>A polymorphism and gastric cancer susceptibility in Eastern Asia. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102401–102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matejcic, M.; Gunter, M.J.; Ferrari, P. Alcohol metabolism and oesophageal cancer: A systematic review of the evidence. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J.D.; Truong, T.; Gaborieau, V.; Chabrier, A.; Chuang, S.C.; Byrnes, G.; Zaridze, D.; Shangina, O.; Szeszenia-Dabrowska, N.; Lissowska, J.; et al. A genome-wide association study of upper aerodigestive tract cancers conducted within the INHANCE consortium. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaue, S.; Akiyama, M.; Hirata, M.; Matsuda, K.; Murakami, Y.; Kubo, M.; Kamatani, Y.; Okada, Y. Functional variants in ADH1B and ALDH2 are non-additively associated with all-cause mortality in Japanese population. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhong, D.; Tong, N.; Chu, H.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, Z. ADH1C Ile350Val polymorphism and cancer risk: Evidence from 35 case-control studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Xie, S.K.; Huang, M.J.; Ren, D.L. Associations of CYP2E1 rs2031920 and rs3813867 polymorphisms with colorectal cancer risk: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 2389–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, X.; Gao, M.; Kong, H.; Li, Y.; Gu, M.; Dong, X.; Niu, W. Synergistic association of PTGS2 and CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms with lung cancer risk in northeastern Chinese. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Oscarson, M.; Johansson, I.; Yue, Q.Y.; Dahl, M.L.; Tabone, M.; Arincò, S.; Albano, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Genetic polymorphism of human CYP2E1: Characterization of two variant alleles. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997, 51, 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Available online: https://www.enzyme-database.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Álvarez-Avellón, S.M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; Vioque, J.; Tardón, A. Effect of alcohol and its metabolites in lung cancer: CAPUA study. Med. Clin. 2017, 148, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quertemont, E. Genetic polymorphism in ethanol metabolism: Acetaldehyde contribution to alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Mol. Psychiatry 2004, 9, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yokoyama, A.; Muramatsu, T.; Ohmori, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Okuyama, K.; Takahashi, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Higuchi, S.; Maruyama, K.; Shirakura, K.; et al. Alcohol-related cancers and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 in Japanese alcoholics. Carcinogenesis 1998, 19, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carr, L.G.; Mellencamp, R.J.; Crabb, D.W.; Weiner, H.; Lumeng, L.; Li, T.K. Polymorphism of the rat liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase cDNA. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1991, 15, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.M.; Chen, C.H.; Yeh, C.C.; Lu, H.J.; Liu, T.T.; Chen, M.H.; Liu, C.Y.; Wu, A.T.H.; Yang, M.H.; Tai, S.K.; et al. Transcriptome analysis and prognosis of ALDH isoforms in human cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seol, J.E.; Kim, J.; Lee, B.H.; Hwang, D.Y.; Jeong, J.; Lee, H.J.; Ahn, Y.O.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, D.H. Folate, alcohol, ADH1B and ALDH2 and colorectal cancer risk. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.J. Gao, Y.H. Aldehyde dehydrogenase with hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2020, 28, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, G.; Mai, R. Alcohol dehydrogenase-1B Arg47His polymorphism and upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk: A meta-analysis including 24,252 subjects. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwantes-An, T.H.; Darlay, R.; Mathurin, P.; Masson, S.; Liangpunsakul, S.; Mueller, S.; Aithal, G.P.; Eyer, F.; Gleeson, D.; Thompson, A.; et al. GenomALC Consortium Genome-wide Association Study and Meta-analysis on Alcohol-Associated Liver Cirrhosis Identifies Genetic Risk Factors. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Yang, P.J.; Lin, S.H.; Yeh, K.T.; Tsao, T.C.; Chen, Y.E.; Lin, S.H.; Yang, S.F. Association between EGFR gene mutation and antioxidant gene polymorphism of non-small-cell lung cancer. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taş, A.; Sılığ, Y.; Pinarbaşi, H.; GüRelık, M. Role of SOD2 Ala16Val polymorphism in primary brain tumors. Biomed. Rep. 2019, 10, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, J.F.; Li, Y.M.; Liu, T.; He, W.T.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.C.; Kang, S.L.; Zeng, X.T.; Zhang, J.Q. Mn-SOD and CuZn-SOD polymorphisms and interactions with risk factors in gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4738–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganne-Carrié, N.; Nahon, P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romeo, S.; Kozlitina, J.; Xing, C.; Pertsemlidis, A.; Cox, D.; Pennacchio, L.A.; Boerwinkle, E.; Cohen, J.C.; Hobbs, H.H. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yuan, X.; Waterworth, D.; Perry, J.R.; Lim, N.; Song, K.; Chambers, J.C.; Zhang, W.; Vollenweider, P.; Stirnadel, H.; Johnson, T.; et al. Population-based genome-wide association studies reveal six loci influencing plasma levels of liver enzymes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, K.; Verset, G.; Trepo, E.; Seth, D. Genetics of alcohol-related hepatocellular carcinoma-its role in risk prediction. Hepatoma Res. 2020, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Kono, S.; Toyomura, K.; Hagiwara, T.; Nagano, J.; Mizoue, T.; Mibu, R.; Tanaka, M.; Kakeji, Y.; Maehara, Y.; et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and A1298C polymorphisms and colorectal cancer: The Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer. Sci. 2004, 95, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, F.F.; Terry, M.B.; Hou, L.; Chen, J.; Lissowska, J.; Yeager, M.; Zatonski, W.; Chanock, S.; Morabia, A.; Chow, W.H. Genetic polymorphisms in folate metabolism and the risk of stomach cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Giovannucci, E.; Kelsey, K.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C.; Hunter, D.J. A methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 4862–4864. [Google Scholar]

- Keku, T.; Millikan, R.; Worley, K.; Winkel, S.; Eaton, A.; Biscocho, L.; Martin, C.; Sandler, R. 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase codon 677 and 1298 polymorphisms and colon cancer in African Americans and whites. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2002, 11, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Ahn, Y.O.; Lee, B.H.; Tsuji, E.; Kiyohara, C.; Kono, S. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, alcohol intake, and risks of colon and rectal cancers in Korea. Cancer Lett. 2004, 216, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Marchand, L.; Wilkens, L.R.; Kolonel, L.N.; Henderson, B.E. The MTHFR C677T polymorphism and colorectal cancer: The multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuo, K.; Ito, H.; Wakai, K.; Hirose, K.; Saito, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kato, T.; Hirai, T.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Hamajima, H.; et al. One-carbon metabolism-related gene polymorphisms interact with alcohol drinking to influence the risk of colorectal cancer in Japan. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slattery, M.L.; Potter, J.D.; Samowitz, W.; Schaffer, D.; Leppert, M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, diet, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1999, 8, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gajalakshmi, V.; Jiang, J.; Kuriki, K.; Suzuki, S.; Nagaya, T.; Nakamura, S.; Akasaka, S.; Ishikawa, H.; Tokudome, S. Associations between 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase codon 677 and 1298 genetic polymorphisms and environmental factors with reference to susceptibility to colorectal cancer: A case-control study in an Indian population. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Arteel, G.E. Effect of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, C.M.; Mancuso, D.J.; Yan, W.; Sims, H.F.; Gibson, B.; Gross, R.W. Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48968–48975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumari, M.; Schoiswohl, G.; Chitraju, C.; Paar, M.; Cornaciu, I.; Rangrez, A.Y.; Wongsiriroj, N.; Nagy, H.M.; Ivanova, P.T.; Scott, S.A.; et al. Adiponutrin functions as a nutritionally regulated lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase. Cell. Metab. 2012, 15, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alegria-Lertxundi, I.; Aguirre, C.; Bujanda, L.; Fernández, F.J.; Polo, F.; Ordovás, J.M.; Etxezarraga, M.C.; Zabalza, I.; Larzabal, M.; Portillo, I.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with susceptibility for development of colorectal cancer: Case-control study in a Basque population. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sud, A.; Kinnersley, B.; Houlston, R.S. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: Current insights and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017, 17, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchankova, P.; Yan, J.; Schwandt, M.L.; Stangl, B.L.; Jerlhag, E.; Engel, J.A.; Hodgkinson, C.A.; Ramchandani, V.A.; Leggio, L. The Leu72Met Polymorphism of the Prepro-ghrelin Gene is Associated With Alcohol Consumption and Subjective Responses to Alcohol: Preliminary Findings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017, 52, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Basu, A.K. DNA Damage, Mutagenesis and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geacintov, N.E.; Broyde, S. Repair-resistant DNA lesions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 1517–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Setshedi, M.; Wands, J.R.; Monte, S.M. Acetaldehyde adducts in alcoholic liver disease. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev 2010, 3, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esterbauer, H.; Schaur, R.J.; Zollner, H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 11, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Uchida, M.; Kanaly, R.A.; Misaki, K.; Shibutani, S.; Kawamoto, T.; Kitagawa, K.; Nakayama, K.I.; Tomokuni, K.; et al. Increased formation of hepatic N2-ethylidene-2′-deoxyguanosine DNA adducts in aldehyde dehydrogenase 2-knockout mice treated with ethanol. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 2363–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sobh, A.; Loguinov, A.; Stornetta, A.; Balbo, S.; Tagmount, A.; Zhang, L.; Vulpe, C.D. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screening Identifies the Tumor Suppressor Candidate OVCA2 As a Determinant of Tolerance to Acetaldehyde. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 169, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaycoechea, J.I.; Crossan, G.P.; Langevin, F.; Mulderrig, L.; Louzada, S.; Yang, F.; Guilbaud, G.; Park, N.; Roerink, S.; Nik-Zainal, S.; et al. Alcohol and endogenous aldehydes damage chromosomes and mutate stem cells. Nature 2018, 553, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccerella, T.; Arslic-Schmitt, T.; Mueller, S.; Linhart, K.B.; Seth, D.; Bartsch, H.; Seitz, H.K. Chronic Ethanol Consumption and Generation of Etheno-DNA Adducts in Cancer-Prone Tissues. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1032, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonohara, Y.; Yamamoto, J.; Tohashi, K.; Takatsuka, R.; Matsuda, T.; Iwai, S.; Kuraoka, I. Acetaldehyde forms covalent GG intrastrand crosslinks in DNA. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sako, M.; Yaekura, I.; Deyashiki, Y. Chemo- and regio-selective modifications of nucleic acids by acetaldehyde and crotonaldehyde. Nucleic Acids Res. Suppl. 2002, 2, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Villalta, P.W.; Wang, M.; Hecht, S.S. Detection and quantitation of acrolein-derived 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts in the human lung by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, F.L.; Zhang, L.; Ocando, J.E.; Nath, R.G. Role of 1, N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts as endogenous DNA lesions in rodents and humans. IARC Sci. Publ. 1999, 150, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schaur, R.J. Basic aspects of the biochemical reactivity of 4-hydroxynonenal. Mol. Asp. Med. 2003, 24, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalleau, S.; Baradat, M.; Guéraud, F.; Huc, L. Cell death and diseases related to oxidative stress: 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in the balance. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stingele, J.; Bellelli, R.; Boulton, S.J. Mechanisms of DNA-protein crosslink repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.A.; López-Sánchez, R.C.; Rendón-Ramírez, A. Lipids and oxidative stress Associated with ethanol-induced neurological damage. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antoniak, D.T.; Duryee, M.J.; Mikuls, T.R.; Thiele, G.M.; Anderson, D.R. Aldehyde-modified proteins as mediators of early inflammation in atherosclerotic disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuma, D.J.; Thiele, G.M.; Xu, D.; Klassen, L.W.; Sorrell, M.F. Acetaldehyde and malondialdehyde react together to generate distinct protein adducts in the liver during long-term ethanol administration. Hepatology 1996, 23, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorn, J.A.; Hurley, T.D.; Petersen, D.R. Inhibition of human mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase by 4-hydroxynon-2-enal and 4-oxonon-2-enal. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, Y.; Hurwitz, E.; Niemelä, O.; Arnon, R. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against acetaldehyde-containing epitopes in acetaldehyde-protein adducts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 7923–7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Niemelä, O.; Parkkila, S.; Juvonen, R.O.; Viitala, K.; Gelboin, H.V.; Pasanen, M. Cytochromes P450 2A6, 2E1, and 3A and production of protein-aldehyde adducts in the liver of patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2000, 33, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitala, K.; Makkonen, K.; Israel, Y.; Lehtimäki, T.; Jaakkola, O.; Koivula, T.; Blake, J.E.; Niemelä, O. Autoimmune responses against oxidant stress and acetaldehyde-derived epitopes in human alcohol consumers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Li, P.; He, F.; Wei, G.; Zhou, Z.; Su, Z.; Ni, T. Comprehensive analysis reveals distinct mutational signatures and mechanistic insights of alcohol consumption in human cancers. Brief Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasekara, H.; MacInnis, R.J.; Williamson, E.J.; Hodge, A.M.; Clendenning, M.; Rosty, C.; Walters, R.; Room, R.; Southey, M.C.; Jenkins, M.A.; et al. Lifetime alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of KRAS+ and BRAF-/KRAS- but not BRAF+ colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amitay, E.L.; Carr, P.R.; Jansen, L.; Roth, W.; Lewers, E.; Herpel, E.; Kloor, M.; Blaker, H.; Chang-Claude, J.; Brenner, H.; et al. Smoking, alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer risk by molecular pathological subtypes and pathways. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chujan, S.; Suriyo, T.; Satayavivad, J. Integrative in silico and in vitro transcriptomics analysis revealed gene expression changes and oncogenic features of normal cholangiocytes after chronic alcohol exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, J.; Sabiha, B.; Jan, H.U.; Haider, S.A.; Khan, A.A.; Ali, S.S. Genetic etiology of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2017, 70, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaździcka, J.; Gołąbek, K.; Strzelczyk, J.K.; Ostrowska, Z. Epigenetic modifications in head and neck cancer. Biochem. Genet. 2020, 58, 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fazio, P.; Matrood, S. Targeting autophagy in liver cancer. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Ramesh, V.; Locasale, J.W. The evolving metabolic landscape of chromatin biology and epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Marioni, R.E.; Hedman, Å.; Pfeiffer, L.; Tsai, P.C.; Reynolds, L.M.; Just, A.C.; Duan, Q.; Boer, C.G.; Tanaka, T.; et al. A DNA methylation biomarker of alcohol consumption. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misawa, K.; Imai, A.; Mochizuki, D.; Mima, M.; Endo, S.; Misawa, Y.; Kanazawa, T.; Mineta, H. Association of TET3 epigenetic inactivation with head and neck cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 24480–24493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, M.A.; Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, D.; Merolla, F.; Varricchio, S.; Salzano, G.; Zarrilli, G.; Mascolo, M.; Strazzullo, V.; Di Crescenzo, R.M.; Celetti, A.; Ilardi, G. Epigenetics of oral and oropharyngeal cancers. Biomed. Rep. 2018, 9, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Yang, H.; Winham, S.J.; Natanzon, Y.; Koestler, D.C.; Luo, T.; Fridley, B.L.; Goode, E.L.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y. Mediation analysis of alcohol consumption, DNA methylation, and epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 63, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, R.G. Alcohol-induced epigenetic changes in cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1856, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.; Anderson, C.; Lippman, S.M. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, diet, and cancer: An update and emerging new evidence. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e457–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.M.; Rudzki, M.; Rudzki, S.; Lewandowski, T.; Laskowska, B. Environmental risk factors for cancer-review paper. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantous, Y.; Schussel, J.L.; Brait, M. Tobacco and alcohol-induced epigenetic changes in oral carcinoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2018, 30, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, S.H.; Nicolaou, A.; Gibbons, W.A. The effect of ethanol and its metabolites upon methionine synthase activity in vitro. Alcohol 1998, 15, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rocco, G.; Baldari, S.; Pani, G.; Toietta, G. Stem cells under the influence of alcohol: Effects of ethanol consumption on stem/progenitor cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shackleton, M.; Quintana, E.; Fearon, E.R.; Morrison, S.J. Heterogeneity in cancer: Cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell 2009, 138, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, L.R.; Imai, S. Specific ablation of Nampt in adult neural stem cells recapitulates their functional defects during aging. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 1321–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khacho, M.; Slack, R.S. Mitochondrial and reactive oxygen species signaling coordinate Stem cell fate decisions and life long maintenance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, P. The axis of mTOR-mitochondria-ROS and stemness of the hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. Cycle 2009, 8, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morita, M.; Oyama, T.; Kagawa, N.; Nakata, S.; Ono, K.; Sugaya, M.; Uramoto, H.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Hanagiri, T.; Sugio, K.; et al. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in the normal esophageal epithelium and alcohol consumption in patients with esophageal cancer. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alison, M.R.; Guppy, N.J.; Lim, S.M.; Nicholson, L.J. Finding cancer stem cells: Are aldehyde dehydrogenases fit for purpose? J. Pathol. 2010, 222, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Sun, Y.E. Epigenetic regulation of stem cell differentiation. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 21R–25R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, F.C.; Balaraman, Y.; Teng, M.; Liu, Y.; Singh, R.P.; Nephew, K.P. Alcohol alters DNA methylation patterns and inhibits neural stem cell differentiation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veazey, K.J.; Carnahan, M.N.; Muller, D.; Miranda, R.C.; Golding, M.C. Alcohol-induced epigenetic alterations to developmentally crucial genes regulating neural stemness and differentiation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, S.; Nguyen, B.N.; Rao, S.; Li, S.; Shetty, K.; Rashid, A.; Shukla, V.; Deng, C.X.; Mishra, L.; Mishra, B. Alcohol, stem cells, and cancer. Genes Cancer 2017, 8, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Serio, R.N. Gudas, L.J. Modification of stem cell states by alcohol and acetaldehyde. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 316, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandeVoort, C.A.; Hill, D.L.; Chaffin, C.L.; Conley, A.J. Ethanol, acetaldehyde, and estradiol affect growth and differentiation of rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 1534–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khalid, O.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hoang, M.; Tu, T.G.; Elie, O.; Lee, C.; Vu, C.; Horvath, S.; Spigelman, I.; et al. Gene expression signatures affected by alcohol-induced DNA methylomic deregulation in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell. Res. 2014, 12, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, M.; Luo, J. Alcohol and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers 2017, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.Y.; Roubal, I.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.S.; Hoang, M.; Mathiyakom, N.; Kim, Y. Alcohol-Induced Molecular Dysregulation in Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Neural Precursor Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Voigt, R.M.; Zhang, Y.; Kato, I.; Xia, Y.; Forsyth, C.B.; Keshavarzian, A.; Sun, J. Alcohol Injury Damages Intestinal Stem Cells. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khalid, O.; Kim, J.J.; Duan, L.; Hoang, M.; Elashoff, D.; Kim, Y. Genome-wide transcriptomic alterations induced by ethanol treatment in human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). Genom. Data 2014, 2, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoang, M.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, Y.; Tong, E.; Trammell, B.; Liu, Y.; Shi, S.; Lee, C.R.; Hong, C.; Wang, C.Y.; et al. Alcohol-induced suppression of KDM6B dysregulates the mineralization potential in dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell. Res. 2016, 17, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, L.; Deshmukh, A.; Prasad, N.; Jang, Y.Y. Alcohol increases liver progenitor populations and induces disease phenotypes in human IPSC-derived mature stage hepatic cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 12, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.M.; Kim, Y.; Shim, J.S.; Park, J.T.; Wang, R.H.; Leach, S.D.; Liu, J.O.; Deng, C.; Ye, Z.; Jang, Y.Y. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2458–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tian, L.; Prasad, N.; Jang, Y.Y. In Vitro Modeling of Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury Using Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1353, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ambade, A.; Satishchandran, A.; Szabo, G. Alcoholic hepatitis accelerates early hepatobiliary cancer by increasing stemness and miR-122-mediated HIF-1alpha activation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chiodi, I. Mondello, C. Lifestyle factors, tumor cell plasticity, and cancer stem cells. Mutat. Res. 2020, 784, 108308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Bonnet, D.; De Maria, R.; Lapidot, T.; Copland, M.; Melo, J.V.; Chomienne, C.; Ishikawa, F.; Schuringa, J.J.; Stassi, G.; et al. Cancer stem cell definitions and terminology: The devil is in the details. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012, 12, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, P.; Chen, K.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Wang, L.; Walters, J.; Shin, Y.J.; Goerger, J.P.; Sun, J.; Witherspoon, M.; Rakhilin, N.; et al. A microRNA miR-34a-regulated bimodal switch targets Notch in colon cancer stem cells. Cell Stem. Cell 2013, 12, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimdahl, B.; Ito, T.; Blevins, A.; Bajaj, J.; Konuma, T.; Weeks, J.; Koechlein, C.S.; Kwon, H.Y.; Arami, O.; Rizzieri, D.; et al. Lis1 regulates asymmetric division in hematopoietic stem cells and in leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajani, J.A.; Song, S.; Hochster, H.S.; Steinberg, I.B. Cancer stem cells: The promise and the potential. Semin. Oncol. 2015, 42, S3–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, P.; Das, B.C. HPV(+ve/-ve) oral-tongue cancer stem cells: A potential target for relapse-free therapy. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 14, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Kwon, H.Y.; Zimdahl, B.; Congdon, K.L.; Blum, J.; Lento, W.E.; Zhao, C.; Lagoo, A.; Gerrard, G.; Foroni, L.; et al. Regulation of myeloid leukaemia by the cell-fate determinant Musashi. Nature 2010, 466, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.; Dong, J.; Haiech, J.; Kilhoffer, M.C.; Zeniou, M. Cancer stem cell quiescence and plasticity as major challenges in cancer therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Angelis, M.L.; Francescangeli, F.; La Torre, F.; Zeuner, A. Stem cell plasticity and dormancy in the development of cancer therapy resistance. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lytle, N.K.; Barber, A.G.; Reya, T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018, 18, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prager, B.C.; Xie, Q.; Bao, S.; Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells: The architects of the tumor ecosystem. Cell. Stem Cell. 2019, 24, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carnero, A.; Garcia-Mayea, Y.; Mir, C.; Lorente, J.; Rubio, I.T.; LLeonart, M.E. The cancer stem-cell signaling network and resistance to therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 49, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Hall, R.R.; Ahmed, A.U. Cancer Stem Cells: Cellular plasticity, niche, and its clinical relevance. J. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 2016, 6, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwobi, O.O.; Harricharran, T.; Huaman, J.; Galuza, A.; Odumuwagun, O.; Tan, Y.; Ma, G.X.; Nguyen, M.T. Mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma progression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2279–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, G.; Fusco, S.; Colavitti, R.; Borrello, S.; Maggiano, N.; Cravero, A.A.; Farre, S.M.; Galeotti, T.; Koch, O.R. Abrogation of hepatocyte apoptosis and early appearance of liver dysplasia in ethanol-fed p53-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 325, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Ren, Z.; Wang, X.; Comer, A.; Frank, J.A.; Ke, Z.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, X.; Wang, S.; et al. ErbB2 and p38gamma MAPK mediate alcohol-induced increase in breast cancer stem cells and metastasis. Mol. Cancer. 2016, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Ren, Z.; Frank, J.A.; Yang, X.H.; Zhang, Z.; Ke, Z.J.; Shi, X.; Luo, J. Chronic ethanol exposure enhances the aggressiveness of breast cancer: The role of p38gamma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3489–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fujihara, K.M.; Clemons, N.J. Bridging the molecular divide: Alcohol-induced downregulation of PAX9 and tumour development. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osei-Sarfo, K.; Tang, X.H.; Urvalek, A.M.; Scognamiglio, T.; Gudas, L.J. The molecular features of tongue epithelium treated with the carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide and alcohol as a model for HNSCC. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, K.; Chen, C.L.; Liu, J.C.; Kashiwabara, C.; Feldman, D.; French, S.W.; Sher, L.; Hyeongnam, J.J.; Tsukamoto, H. Cancer stem cells generated by alcohol, diabetes, and hepatitis C virus. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, X.; Yin, N.; Ma, S.; Lepp, A.; Tang, J.; Jing, W.; Johnson, B.; Dwinell, M.B.; Chitambar, C.R.; Chen, G. p38gamma MAPK is a therapeutic target for triple-negative breast cancer by stimulation of cancer stem-like cell expansion. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 2738–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.; Sharma, S.; Teknos, T.N. RhoC regulates cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by overexpressing IL-6 and phosphorylation of STAT. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Mishra, L.; Machida, K. Alcohol, TLR4-TGF-beta antagonism, and liver cancer. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.L.; Tsukamoto, H.; Liu, J.C.; Kashiwabara, C.; Feldman, D.; Sher, L.; Dooley, S.; French, S.W.; Mishra, L.; Petrovic, L.; et al. Reciprocal regulation by TLR4 and TGF-beta in tumor-initiating stem-like cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 2832–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machida, K.; Feldman, D.E.; Tsukamoto, H. TLR4-dependent tumor-initiating stem cell-like cells (TICs) in alcohol-associated hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 815, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machida, K. Cell fate, metabolic reprogramming and lncRNA of tumor-initiating stem-like cells induced by alcohol. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 323, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hritz, I.; Mandrekar, P.; Velayudham, A.; Catalano, D.; Dolganiuc, A.; Kodys, K.; Kurt-Jones, E.; Szabo, G. The critical role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter. MyDHepatology 2008, 48, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Yang, W.; Toprani, S.M.; Guo, W.; He, L.; DeLeo, A.B.; Ferrone, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, E.; Lin, Z.; et al. Induction of immunogenic cell death in radiation-resistant breast cancer stem cells by repurposing anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram. Cell. Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, D.; Yu, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Deng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is involved in ethanol promoted hepatocellular carcinoma cells metastasis and stemness. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen-Mancina, E.; Calderon-Montano, J.M.; Lopez-Lazaro, M. Avoiding the ingestion of cytotoxic concentrations of ethanol may reduce the risk of cancer associated with alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 183, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon-Montano, J.M.; Jimenez-Alonso, J.J.; Guillen-Mancina, E.; Burgos-Moron, E.; Lopez-Lazaro, M. A 30-s exposure to ethanol 20% is cytotoxic to human keratinocytes: Possible mechanistic link between alcohol-containing mouthwashes and oral cancer. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2943–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M. A local mechanism by which alcohol consumption causes cancer. Oral Oncol. 2016, 62, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tapani, E.; Taavitsainen, M.; Lindros, K.; Vehmas, T.; Lehtonen, E. Toxicity of ethanol in low concentrations. Experimental evaluation in cell culture. Acta Radiol. 1996, 37, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.J.; Khalid, O.; Duan, L.; Kim, R.; Elashoff, D.; Kim, Y. Gene expression signatures affected by ethanol and/or nicotine in normal human normal oral keratinocytes (NHOKs). Genom. Data 2014, 2, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, W.; Ma, Y.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Chronic ethanol exposure of human pancreatic normal ductal epithelial cells induces cancer stem cell phenotype through SATB. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ye, S.; Zhou, X.; Liu, D.; Ying, Q.L. Molecular basis of embryonic stem cell self-renewal: From signaling pathways to pluripotency network. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 1741–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, W.; Ma, Y.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Role of SATB2 in human pancreatic cancer: Implications in transformation and a promising biomarker. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57783–57797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Witte, K.E.; Hertel, O.; Windmoller, B.A.; Helweg, L.P.; Hoving, A.L.; Knabbe, C.; Busche, T.; Greiner, J.F.W.; Kalinowski, J.; Noll, T.; et al. Nanopore sequencing reveals global transcriptome signatures of mitochondrial and ribosomal gene expressions in various human cancer stem-like cell populations. Cancers 2021, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clara, J.A.; Monge, C.; Yang, Y.; Takebe, N. Targeting signaling pathways and the immune microenvironment of cancer stem cell-a clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Hannafon, B.N.; Ding, W.Q. Disulfiram’s Anticancer Activity: Evidence and Mechanisms. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, I.; Srivastava, S.K. Cancer cells stemness: A doorstep to targeted therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Dueñas, C.; Hauer, J.; Cobaleda, C.; Borkhardt, A.; Sánchez-García, I. Epigenetic priming in cancer initiation. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]