The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. History—Medical and Surgical Evolutions of Lung Cancer

2.1. Lung Cancer Epidemiology—Past and Recent Trends

2.2. Lung Cancer Screening Programs

2.3. Developments in “Medicine”, Re-Thinking Care

2.3.1. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery and Prehabilitation

2.3.2. Quality of Life Assessments—“Surgery for a Better Life”

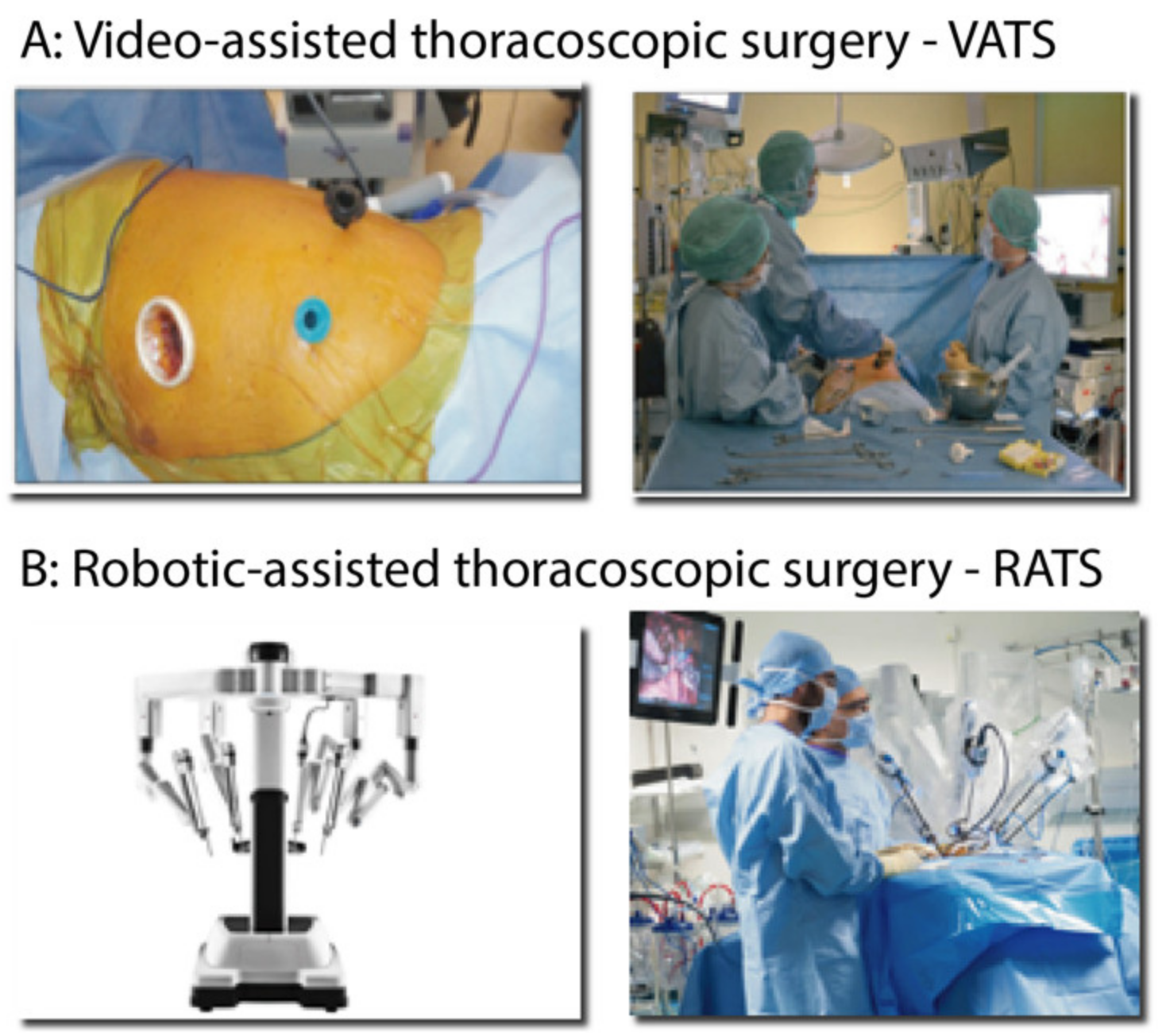

2.4. History of Lung Cancer Surgery, from Past to Current Trends—“Smaller Is Better”

2.5. Operating on Our Elders—A Switch to Radiotherapy?

3. Lung Cancer and Surgical Treatment

3.1. Surgical Treatment for Cancer Patients Today

3.2. Surgical Treatment for Early Stages—Stage I NSCLC

3.2.1. Surgical Options

3.2.2. “Resecting Less”, Segmentectomy for Early-Stage NSCLC, from Present to Future

3.2.3. Surgical Approaches for Segmentectomy

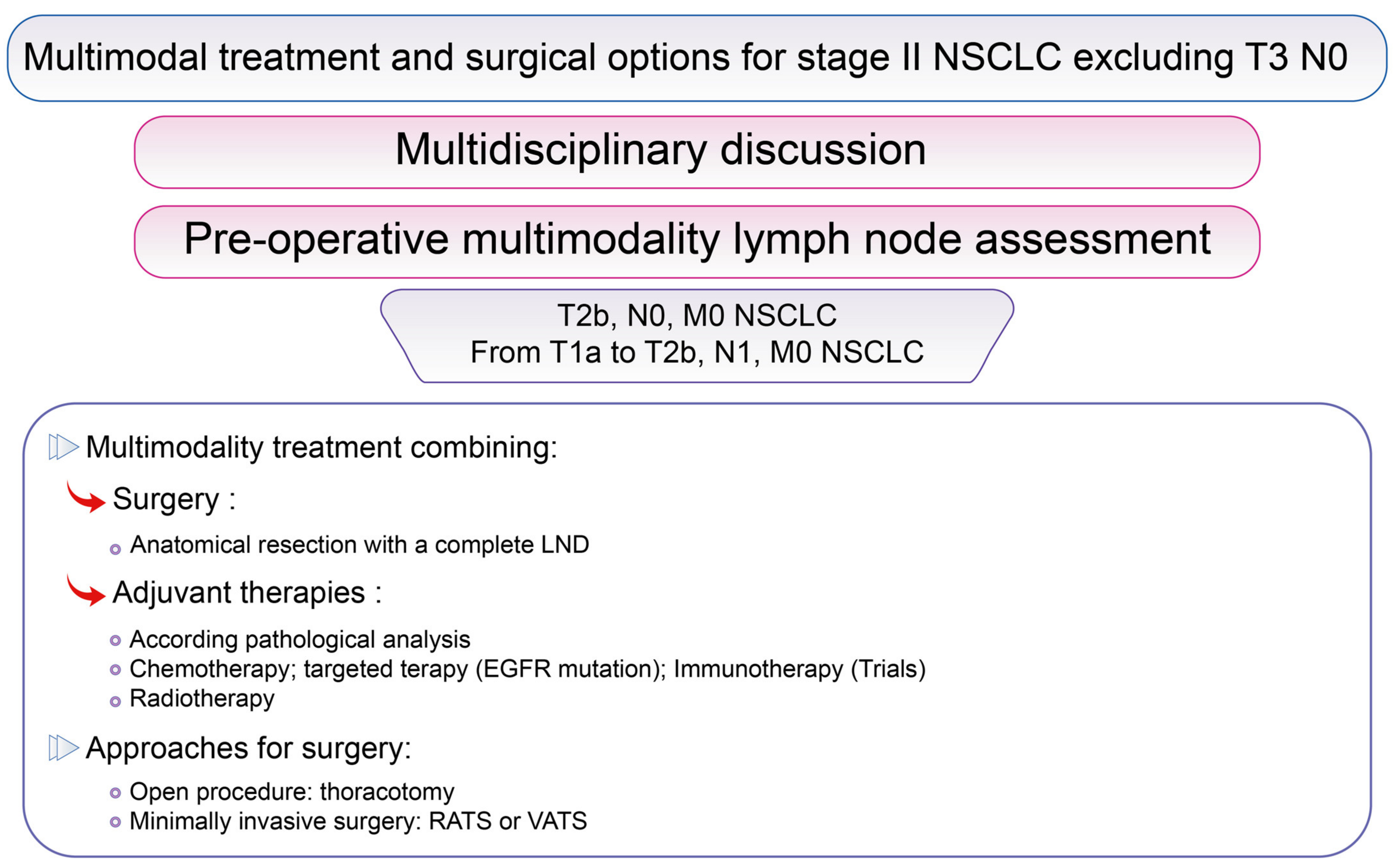

3.3. Surgical Options for Resectable Stage II NSCLC Excluding cT3 N0

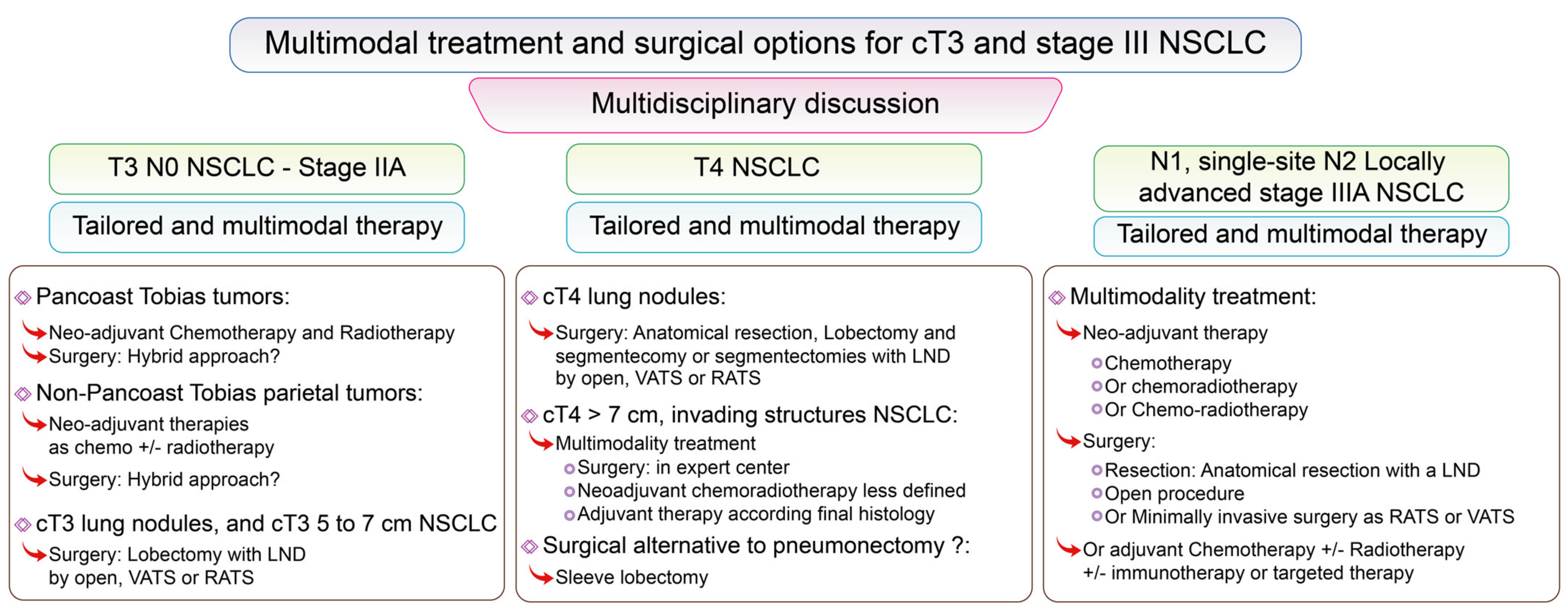

3.4. Surgical Options for Stage III NSCLC Including T3, from Present to Future

3.4.1. Surgery for cT3 NSCLC

3.4.2. Surgery for cT4 NSCLC

3.4.3. Redefining the Role of Pneumonectomy, “Surgical Haute Couture”

3.4.4. Locally Advanced NSCLC

3.4.5. Surgery for N3 NSCLC

3.5. Surgery for Stage IV NSCLC

3.6. “Recuperative Surgery” and “Salvage Surgery”

4. Surgery in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Symptoms

5. Future Perspectives

5.1. From ERAS to Ambulatory Surgical Care

5.2. Redefining Functional Assessments

5.3. Hybrid Surgical Approach or Local Treatment, “Thinking Green Surgery”

5.4. Resecting after Innovative Systemic Treatment, Future Perspectives

5.5. Providing Adequate Cares for All

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barta, J.A.; Powell, C.A.; Wisnivesky, J.P. Global Epidemiology of Lung Cancer. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, D.R.; Adams, A.M.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Clapp, J.D. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N. Engl. J Med. 2011, 365, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Koning, H.J.; van der Aalst, C.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.W.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, S.; Maringe, C.; Coleman, M.; Peake, M.D.; Butler, J.; Young, N.; Bergström, S.; Hanna, L.; Jakobsen, E.; Kölbeck, K.; et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK: A population-based study, 2004–2007. Thorax 2013, 68, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Francisci, S.; Minicozzi, P.; Pierannunzio, D.; Ardanaz, E.; Eberle, A.; Grimsrud, T.K.; Knijn, A.; Pastorino, U.; Salmerón, D.; Trama, A.; et al. Survival patterns in lung and pleural cancer in Europe 1999–2007: Results from the EUROCARE-5 study. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2242–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, P.E.; Strasser-Weippl, K.; Lee-Bychkovsky, B.L.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Liedke, P.E.; Pramesh, C.S.; Badovinac-Crnjevic, T.; Sheikine, Y.; et al. Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 489–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehlet, H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br. J. Anaesth. 1997, 78, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, T.J.P.; Rasburn, N.J.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Brunelli, A.; Cerfolio, R.; Gonzalez, M.; Ljungqvist, O.; Petersen, R.H.; Popescu, W.M.; Slinger, P.D.; et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: Recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS ®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 55, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, T.J.P.; Ljungqvist, O. A surgical perspective of ERAS guidelines in thoracic surgery. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 32, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.J.; Bleetman, D.; Messenger, D.E.; Joshi, N.A.; Wood, L.; Rasburn, N.J.; Batchelor, T. The impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol compliance on morbidity from resection for primary lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gravier, F.-E.; Bonnevie, T.; Boujibar, F.; Médrinal, C.; Prieur, G.; Combret, Y.; Muir, J.-F.; Cuvelier, A.; Baste, J.-M.; Debeaumont, D. Effect of prehabilitation on ventilatory efficiency in non–small cell lung cancer patients: A cohort study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 157, 2504–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujibar, F.; Bonnevie, T.; Debeaumont, D.; Bubenheim, M.; Cuvellier, A.; Peillon, C.; Gravier, F.-E.; Baste, J.-M. Impact of prehabilitation on morbidity and mortality after pulmonary lobectomy by minimally invasive surgery: A cohort study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padilla, G.V.; Ferrell, B.; Grant, M.M.; Rhiner, M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nurs. 1990, 13, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Cheville, A.L.; Wampfler, J.A.; Garces, Y.I.; Jatoi, A.; Clark, M.M.; Cassivi, S.D.; Midthun, D.E.; Marks, R.S.; Aubry, M.-C.; et al. Quality of Life and Symptom Burden among Long-Term Lung Cancer Survivors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yip, R.; Taioli, E.; Schwartz, R.; Li, K.; Becker, B.J.; Tam, K.; Htwe, Y.M.; Yankelevitz, D.F.; Henschke, C.I. A Review of Quality of Life Measures used in Surgical Outcomes for Stage I Lung Cancers. Cancer Investig. 2018, 36, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, C.; Koller, M.; Velikova, G. Choosing the right survey: The lung cancer surgery. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 6892–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E.S.; Kneuertz, P.J.; Nishimura, J.; D’Souza, D.M.; Diefenderfer, E.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.D.; Merritt, R.E. Effect of operative approach on quality of life following anatomic lung cancer resection. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 6913–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, K.; Blazeby, J.; Chalmers, K.A.; Batchelor, T.J.P.; Casali, G.; Internullo, E.; Krishnadas, R.; Evans, C.; West, D. Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery for Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 27, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, E.A.; Singer, J.J. Successful Removal of an Entire Lung for Carcinoma of the Bronchus. Jama. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1933, 101, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.; Johnson, D.H.; Evarts, A. Graham and the First Pneumonectomy for Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3268–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, E.D.; Sweet, R.H.; Soutter, L.; Scannell, J.G. The surgical management of carcinoma of the lung; a study of the cases treated at the Massachusetts General Hospital from 1930 to 1950. J. Thorac. Surg. 1950, 20, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, W.G. Radical lobectomy. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1960, 39, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, N.; Flehinger, B.J. The Role of Surgery in N2 Lung Cancer. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1987, 67, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, R.J.; Rubinstein, L.V. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995, 60, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, R.J. The role of induction therapy and surgery for stage IIIA lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 1995, 6, S29–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vansteenkiste, J.; Crino, L.; Dooms, C.; Douillard, J.Y.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Lim, E.; Rocco, G.; Senan, S.; Van Schil, P.; Veronesi, G.; et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: Early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer consensus on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmus, P.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Oudkerk, M.; Senan, S.; Waller, D.A.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Escriu, C.; Peters, S. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28 (Suppl. 4), iv1–iv21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, L.Ø.; Petersen, R.H.; Hansen, H.J.; Jensen, T.K.; Ravn, J.; Konge, L. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy for lung cancer is associated with a lower 30-day morbidity compared with lobectomy by thoracotomy. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 49, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, P.-B.; Delpy, J.-P.; Orsini, B.; Gossot, D.; Baste, J.-M.; Thomas, P.; Dahan, M.; Bernard, A. Propensity Score Analysis Comparing Videothoracoscopic Lobectomy With Thoracotomy: A French Nationwide Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 101, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcoz, P.-E.; Puyraveau, M.; Thomas, P.; Decaluwe, H.; Hürtgen, M.; Petersen, R.H.; Hansen, H.; Brunelli, A.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Dahan, M.; et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus open lobectomy for primary non-small-cell lung cancer: A propensity-matched analysis of outcome from the European Society of Thoracic Surgeon database. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 49, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.; Jørgensen, O.D.; Kronborg, C.; Andersen, C.; Licht, P.B. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early stage lung cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Isaacs, A.; Treasure, T.; Altorki, N.K.; Sedrakyan, A. Long term survival with thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy: Propensity matched comparative analysis using SEER-Medicare database. BMJ 2014, 349, g5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, S.; Sedrakyan, A.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Nasar, A.; Port, J.L.; Lee, P.C.; Stiles, B.M.; Altorki, N.K. Outcomes after lobectomy using thoracoscopy vs thoracotomy: A comparative effectiveness analysis utilizing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013, 43, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paul, S.; Altorki, N.K.; Sheng, S.; Lee, P.C.; Harpole, D.H.; Onaitis, M.W.; Stiles, B.M.; Port, J.L.; D’Amico, T.A. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: A propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lim, E.; Batchelor, T.; Shackcloth, M.; Dunning, J.; Mcgonigle, N.; Brush, T.; Dabner, L.; Harris, R.; Mckeon, H.; Paramasivan, S.; et al. Study protocol for VIdeo assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy versus conventional Open LobEcTomy for lung cancer, a UK multicentre randomised controlled trial with an internal pilot (the VIOLET study). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, C.S.; MacDonald, J.K.; Gilbert, S.; Khan, A.Z.; Kim, Y.T.; Louie, B.E.; Marshall, M.B.; Santos, R.S.; Scarci, M.; Shargal, Y.; et al. Optimal Approach to Lobectomy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Innov. Technol. Tech. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 14, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, L.; Shen, Y.; Onaitis, M. Comparative study of anatomic lung resection by robotic vs. video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.E.; Kreaden, U.S.; Hebert, A.E.; Eaton, D.; Redmond, K.C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of robotic versus open and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery approaches for lobectomy. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 28, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Chen, M.; Chen, N.; Liu, L. Feasibility and safety of robot-assisted thoracic surgery for lung lobectomy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.; Wang, T.; Whyte, R.; Curran, T.; Flores, R.; Gangadharan, S. Open, Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery, and Robotic Lobectomy: Review of a National Database. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.D.; Bolton, W.D.; Stephenson, J.E.; Henry, G.; Robbins, E.T.; Sommers, E. Initial Multicenter Community Robotic Lobectomy Experience: Comparisons to a National Database. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.; Raja, S.; Bribriesco, A.C.; Raymond, D.P.; Sudarshan, M.; Murthy, S.C.; Ahmad, U. Robotic Approach Offers Similar Nodal Upstaging to Open Lobectomy for Clinical Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennon, M.W.; Degraaff, L.H.; Groman, A.; Demmy, T.L.; Yendamuri, S. The association of nodal upstaging with surgical approach and its impact on long-term survival after resection of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 57, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-F.J.; Kumar, A.; Deng, J.Z.; Raman, V.; Lui, N.S.; D’Amico, T.A.; Berry, M.F. A National Analysis of Short-term Outcomes and Long-term Survival Following Thoracoscopic Versus Open Lobectomy for Clinical Stage II Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirafa, C.; Aprile, V.; Ricciardi, S.; Romano, G.; Davini, F.; Cavaliere, I.; Alì, G.; Fontanini, G.; Melfi, F. Nodal upstaging evaluation in NSCLC patients treated by robotic lobectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio, R.; Ghanim, A.F.; Dylewski, M.; Veronesi, G.; Spaggiari, L.; Park, B.J. The long-term survival of robotic lobectomy for non–small cell lung cancer: A multi-institutional study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medbery, R.L.; Gillespie, T.W.; Liu, Y.; Nickleach, D.C.; Lipscomb, J.; Sancheti, M.S.; Pickens, A.; Force, S.D.; Fernandez, F.G. Nodal Upstaging Is More Common with Thoracotomy than with VATS During Lobectomy for Early-Stage Lung Cancer: An Analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, J.L.; Louie, B.E.; Cerfolio, R.; Park, B.J.; Vallieres, E.; Aye, R.; Abdel-Razek, A.; Bryant, A.; Farivar, A. The Prevalence of Nodal Upstaging During Robotic Lung Resection in Early Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 1901–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, R.E.; Hoang, C.D.; Shrager, J.B. Lymph Node Evaluation Achieved by Open Lobectomy Compared With Thoracoscopic Lobectomy for N0 Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 96, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffa, D.J.; Kosinski, A.S.; Paul, S.; Mitchell, J.D.; Onaitis, M. Lymph Node Evaluation by Open or Video-Assisted Approaches in 11,500 Anatomic Lung Cancer Resections. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 94, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneuertz, P.J.; D’Souza, D.M.; Richardson, M.; Abdel-Rasoul, M.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.D.; Merritt, R.E. Long-Term Oncologic Outcomes After Robotic Lobectomy for Early-stage Non–Small-cell Lung Cancer Versus Video-assisted Thoracoscopic and Open Thoracotomy Approach. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, 214–224.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesti, J.; Langan, R.C.; Bell, J.; Nguyen, A.; Turner, A.; Hilden, P.; Leshchuk, K.; Dabrowski, M.; Paul, S. A Comparative Analysis of Long-Term Survival of Robotic Versus Thoracoscopic Lobectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluswamy, R.R.; Brown, S.-A.W.; Mhango, G.; Sigel, K.; Nicastri, D.G.; Smith, C.B.; Bonomi, M.; Galsky, M.D.; Taioli, E.; Neugut, A.I.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Robotic-Assisted Surgery for Resectable Lung Cancer in Older Patients. Chest 2020, 157, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-F.J.; Kumar, A.; Klapper, J.A.; Hartwig, M.G.; Tong, B.C.; Harpole, D.H.; Berry, M.F.; D’Amico, T.A. A National Analysis of Long-term Survival Following Thoracoscopic Versus Open Lobectomy for Stage I Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaggiari, L.; Sedda, G.; Maisonneuve, P.; Tessitore, A.; Casiraghi, M.; Petrella, F.; Galetta, D. A Brief Report on Survival After Robotic Lobectomy for Early-Stage Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Melfi, F.; Mussi, A.; Maisonneuve, P.; Spaggiari, L.; Da Silva, R.K.C.; Veronesi, G. Robotic lobectomy for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Long-term oncologic results. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012, 143, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, W. Operative Mortality and Five-Year Survival Rates in Men with Bronchogenic Carcinoma. Chest 1974, 66, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, P.-B.; Cottenet, J.; Mariet, A.-S.; Bernard, A.; Quantin, C. In-hospital mortality following lung cancer resection: Nationwide administrative database. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitra, T.-C.; Molina, J.-C.; Mouhanna, J.; Nicolau, I.; Renaud, S.; Aubin, L.; Siblini, A.; Mulder, D.; Ferri, L.; Spicer, J. Feasibility analysis for the development of a video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) lobectomy 23-h recovery pathway. Can. J. Surg. 2020, 63, E349–E358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagan, P.; Berna, P.; De Dominicis, F.; Lafitte, S.; Zaimi, R.; Dakhil, B.; Pereira, J.-C.D.N. Chirurgie thoracique ambulatoire: Évolution des indications, applications actuelles et limites. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2016, 33, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardet, J.; Zaimi, R.; Dakhil, B.; Couffinhal, J.C.; Raynaud, C.; Bagan, P. Résection thoracoscopique ambulatoire de nodules pulmonaires dans le cadre de la réhabilitation précoce. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2016, 33, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozower, B.D.; Larner, J.M.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Jones, D.R. Special Treatment Issues in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2013, 143, e369S–e399S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, P.; Dahan, M.; Riquet, M.; Massart, G.; Falcoz, P.E.; Brouchet, L.; Barthes, F.L.P.; Doddoli, C.; Martinod, E.; Fadel, E. Pratiques chirurgicales dans le traitement du cancer primitif non à petites cellules du poumon Recommandations de la SFCTCV: Pratiques chirurgicales dans le traitement du cancer du poumon. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2008, 25, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardinois, D.; De Leyn, P.; Van Schil, P.; Porta, R.R.; Waller, D.; Passlick, B.; Zielinski, M.; Junker, K.; Rendina, E.A.; Ris, H.B.; et al. ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2006, 30, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rami-Porta, R.; Wittekind, C.; Goldstraw, P. Complete resection in lung cancer surgery: Proposed definition. Lung Cancer 2005, 49, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhles, S.; Macbeth, F.; Treasure, T.; Younes, R.N.; Rintoul, R.; Fiorentino, F.; Bogers, A.J.J.C.; Takkenberg, J.J.M. Systematic lymphadenectomy versus sampling of ipsilateral mediastinal lymph-nodes during lobectomy for non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review of randomized trials and a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 51, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Hu, J. Lymphadenectomy for clinical early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 50, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darling, G.E.; Allen, M.S.; Decker, P.A.; Ballman, K.; Malthaner, R.A.; Inculet, R.I.; Jones, D.R.; McKenna, R.J.; Landreneau, R.J.; Rusch, V.; et al. Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non–small cell carcinoma: Results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 Trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keller, S.M.; Adak, S.; Wagner, H.; Johnson, D.H. Mediastinal lymph node dissection improves survival in patients with stages II and IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000, 70, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishida, T.; Miyaoka, E.; Yokoi, K.; Tsuboi, M.; Asamura, H.; Kiura, K.; Takahashi, K.; Dosaka-Akita, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Date, H.; et al. Lobe-Specific Nodal Dissection for Clinical Stage I and II NSCLC: Japanese Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study Using a Propensity Score Analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okada, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Yuki, T.; Mimura, T.; Miyoshi, K.; Tsubota, N. Selective Mediastinal Lymphadenectomy for Clinico-Surgical Stage I Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2006, 81, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimasu, T.; Miyoshi, S.; Oura, S.; Hirai, I.; Kokawa, Y.; Okamura, Y. Limited mediastinal lymph node dissection for non-small cell lung cancer according to intraoperative histologic examinations. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 130, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miyoshi, S.; Maebeya, S.; Suzuma, T.; Bessho, T.; Hirai, I.; Tanino, H.; Yoshimasu, T.; Arimoto, J.; Naito, Y.; Nishino, E. Which Mediastinal Lymph Nodes should be Examined During Operation for Diagnosing NO or Ni Disease in Bronchogenic Carcinoma? Haigan 1997, 37, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pallis, A.G.; Gridelli, C.; Wedding, U.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Veronesi, G.; Jaklitsch, M.; Luciani, A.; O’Brien, M. Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert’s opinion paper: EORTC Elderly Task Force, Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncology. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluswamy, R.R.; Ezer, N.; Mhango, G.; Goodman, E.; Bonomi, M.; Neugut, A.I.; Swanson, S.J.; Powell, C.; Beasley, M.B.; Wisnivesky, J.P. Limited Resection Versus Lobectomy for Older Patients With Early-Stage Lung Cancer: Impact of Histology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3447–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shapiro, M.; Mhango, G.; Kates, M.; Weiser, T.; Chin, C.; Swanson, S.; Wisnivesky, J. Extent of lymph node resection does not increase perioperative morbidity and mortality after surgery for stage I lung cancer in the elderly. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2012, 38, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, C.; Falcoz, P.-E.; Rami-Porta, R.; Velly, J.-F.; Begueret, H.; Roques, X.; Dahan, M.; Jougon, J. Mediastinal lymphadenectomy in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 44, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiter, J.C.d.; Heineman, D.J.; Daniels, J.M.; Diessen, J.N.; van Damhuis, R.A.; Hartemink, K.J. The role of surgery for stage I non-small cell lung cancer in octogenarians in the era of stereotactic body radiotherapy in the Netherlands. Lung Cancer 2020, 144, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaji, M. Surgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: Prospective clinical trials of the past, the present, and the future. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 68, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchard, D.; Popat, S.; Kerr, K.; Novello, S.; Smit, E.F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Mok, T.S.; Reck, M.; Van Schil, P.E.; Hellmann, M.D.; et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 4), iv192–iv237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, S.S.; Fernandez, F.; Higgins, K.A.; Auffermann, W.F.; Khuri, F.R. Lung. TNM Online 2017, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Chandrakumar, D.; Gupta, S.; Yan, T.; Tian, D.H. Could less be more?—A systematic review and meta-analysis of sublobar resections versus lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer according to patient selection. Lung Cancer 2015, 89, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schil, P.E.; Balduyck, B.; De Waele, M.; Hendriks, J.; Hertoghs, M.; Lauwers, P. Surgical treatment of early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2013, 11, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Winckelmans, T.; Decaluwé, H.; Leyn, P.D.; Raemdonck, D.V. Segmentectomy or lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 57, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Saji, H.; Aokage, K.; Watanabe, S.-I.; Okada, M.; Mizusawa, J.; Nakajima, R.; Tsuboi, M.; Nakamura, S.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Comparison of pulmonary segmentectomy and lobectomy: Safety results of a randomized trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 158, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altorki, N.K.; Wang, X.; Wigle, D.; Gu, L.; Darling, G.; Ashrafi, A.S.; Landrenau, R.; Miller, D.; Liberman, M.; Jones, D.R.; et al. Perioperative mortality and morbidity after sublobar versus lobar resection for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: Post-hoc analysis of an international, randomised, phase 3 trial (CALGB/Alliance 140503). Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsam, M.; Baste, J.-M.; Lachkar, S. Multidisciplinary approach to minimally invasive lung segmentectomy. J. Vis. Surg. 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baste, J.M.; Soldea, V.; Lachkar, S.; Rinieri, P.; Sarsam, M.; Bottet, B.; Peillon, C. Development of a precision multimodal surgical navigation system for lung robotic segmentectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S1195–S1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lachkar, S.; Guisier, F.; Roger, M.; Bota, S.; Lerouge, D.; Piton, N.; Thiberville, L.; Salaün, M. A simple endoscopic method with radial endobronchial ultrasonography for low-migration rate coil-tailed fiducial marker placement. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachkar, S.; Baste, J.-M.; Thiberville, L.; Peillon, C.; Rinieri, P.; Piton, N.; Guisier, F.; Salaün, M. Pleural Dye Marking Using Radial Endobronchial Ultrasound and Virtual Bronchoscopy before Sublobar Pulmonary Resection for Small Peripheral Nodules. Respiration 2018, 95, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Yamada, T.; Menju, T.; Aoyama, A.; Sato, T.; Chen, F.; Sonobe, M.; Omasa, M.; Date, H. Virtual-assisted lung mapping: Outcome of 100 consecutive cases in a single institute†. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015, 47, e131–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aoun, H.D.; Littrup, P.J.; Heath, K.E.; Adam, B.; Prus, M.; Beydoun, R.; Baciewcz, F. Methylene Blue/Collagen Mixture for CT-Guided Presurgical Lung Nodule Marking: High Efficacy and Safety. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 31, 1682.e1–1682.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Yue, W.; Lu, M.; Tian, H. Comparison of computed tomographic imaging-guided hook wire localization and electromagnetic navigation bronchoscope localization in the resection of pulmonary nodules: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nex, G.; Schiavone, M.; De Palma, A.; Quercia, R.; Brascia, D.; De Iaco, G.; Signore, F.; Panza, T.; Marulli, G. How to identify intersegmental planes in performing sublobar anatomical resections. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3369–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, L.; Nicolau, S.; Pessaux, P.; Mutter, D.; Marescaux, J. Real-time 3D image reconstruction guidance in liver resection surgery. HepatoBiliary Surg. Nutr. 2014, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bédat, B.; Triponez, F.; Sadowski, S.M.; Ellenberger, C.; Licker, M.; Karenovics, W. Impact of near-infrared angiography on the quality of anatomical resection during video-assisted thoracic surgery segmentectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S1229–S1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guigard, S.; Triponez, F.; Bédat, B.; Vidal-Fortuny, J.; Licker, M.; Karenovics, W. Usefulness of near-infrared angiography for identifying the intersegmental plane and vascular supply during video-assisted thoracoscopic segmentectomy†. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 25, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, C.-H.; Chao, Y.-K.; Liu, Y.-H.; Wen, C.-T.; Chen, W.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Hsieh, M.-J.; Wu, Y.-C.; Liu, H.-P. Clinical use of near-infrared fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green in thoracic surgery: A literature review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, S744–S748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, A.; Deng, J.Z.; Raman, V.; Okusanya, O.T.; Baiu, I.; Berry, M.F.; D’Amico, T.A.; Yang, C.-F.J. A National Analysis of Minimally Invasive Vs Open Segmentectomy for Stage IA Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 33, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabra, M.; Alwatari, Y.; Bierema, C.; Wolfe, L.G.; Cassano, A.D.; Shah, R.D. Five-Year Experience with VATS Versus Thoracotomy Segmentectomy for Lung Tumor Resection. Innov. Technol. Tech. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 15, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgi, Z.; Swanson, S.J. Current indications and outcomes for thoracoscopic segmentectomy for early stage lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, S1662–S1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio, R.J.; Watson, C.; Minnich, D.J.; Calloway, S.; Wei, B. One Hundred Planned Robotic Segmentectomies: Early Results, Technical Details, and Preferred Port Placement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 101, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutz, J.A.; Seguin-Givelet, A.; Grigoroiu, M.; Brian, E.; Girard, P.; Gossot, D. Oncological results of full thoracoscopic major pulmonary resections for clinical Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 55, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Gharagozloo, F.; Tempesta, B.; Meyer, M.; Gruessner, A. Long-term results of robotic anatomical segmentectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, J.; Pan, F.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Song, W.; Luo, Q. Operative outcomes and long-term survival of robotic-assisted segmentectomy for stage IA lung cancer compared with video-assisted thoracoscopic segmentectomy. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, S.; Shimizu, K.; Mogi, A.; Kuwano, H. VATS segmentectomy: Past, present, and future. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondé, H.; Laurent, M.; Gillibert, A.; Sarsam, M.; Varin, R.; Grimandi, G.; Peillon, C.; Baste, J.-M. The affordability of minimally invasive procedures in major lung resection: A prospective study. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 25, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinieri, P.; Peillon, C.; Salaün, M.; Mahieu, J.; Bubenheim, M.; Baste, J.-M. Perioperative outcomes of video- and robot-assisted segmentectomies. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2016, 24, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leyn, P.; Dooms, C.; Kuzdzal, J.; Lardinois, D.; Passlick, B.; Rami-Porta, R.; Turna, A.; Van Schil, P.; Venuta, F.; Waller, D.; et al. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 45, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-Y.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Chao, H.-S.; Chiu, C.-H.; Hsu, W.-H.; Hsu, H.-S.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chou, T.-Y.; Chen, C.-K.; Lan, K.-L.; et al. Multidisciplinary team discussion results in survival benefit for patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, W.E.; De Ruysscher, D.; Weder, W.; Le Péchoux, C.; De Leyn, P.; Hoffmann, H.; Westeel, V.; Stahel, R.; Felip, E.; Peters, S.; et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference in Lung Cancer: Locally advanced stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, J.R.; Woodard, G.; Jablons, D.M. Management of Lung Cancer Invading the Superior Sulcus. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2017, 27, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, V.D.; Fazzotta, S.; Fatica, F.; D’Orazio, B.; Caronia, F.P.; Cajozzo, M.; Damiano, G.; Maffongelli, A.; Cudia, B.M.; Messina, M.; et al. Pancoast tumour: Current therapeutic options. La Clin Terapeutica 2019, 170, e291–e294. [Google Scholar]

- Mariolo, A.V.; Casiraghi, M.; Galetta, D.; Spaggiari, L. Robotic Hybrid Approach for an Anterior Pancoast Tumor in a Severely Obese Patient. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, e115–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caronia, F.P.; Fiorelli, A.; Ruffini, E.; Nicolosi, M.; Santini, M.; Monte, A.I.L. A comparative analysis of Pancoast tumour resection performed via video-assisted thoracic surgery versus standard open approaches. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 19, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guberina, N.; Pöttgen, C.; Schuler, M.; Guberina, M.; Stamatis, G.; Plönes, T.; Krebs, B.; Metzenmacher, M.; Theegarten, D.; Gauler, T.; et al. Comparison of early tumour-associated versus late deaths in patients with central or >7 cm T4 N0/1 M0 non-small-cell lung-cancer undergoing trimodal treatment: Only few risks left to improve. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 138, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, Z.M.; Shen, K.R.; Yendamuri, S.; Cassivi, S.; Nichols, F.C.; Wigle, D.A.; Allen, M.S.; Blackmon, S.H. Outcomes After Sleeve Lung Resections Versus Pneumonectomy in the United States. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 104, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cusumano, G.; Marra, A.; Lococo, F.; Margaritora, S.; Siciliani, A.; Maurizi, G.; Poggi, C.; Hillejan, L.; Rendina, E.; Granone, P. Is Sleeve Lobectomy Comparable in Terms of Short- and Long-Term Results With Pneumonectomy After Induction Therapy? A Multicenter Analysis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizi, G.; D’Andrilli, A.; Anile, M.; Ciccone, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.; Venuta, F.; Rendina, E.A. Sleeve Lobectomy Compared with Pneumonectomy after Induction Therapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2013, 8, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, A.; Fan, J.; Cheng, H. Does sleeve lobectomy concomitant with or without pulmonary artery reconstruction (double sleeve) have favorable results for non-small cell lung cancer compared with pneumonectomy? A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2007, 32, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.; Stoelben, E.; Olschewski, M.; Hasse, J. Comparison of Morbidity, 30-Day Mortality, and Long-Term Survival After Pneumonectomy and Sleeve Lobectomy For Non–Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005, 79, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.-Y.; Qiu, X.-M.; Zhu, D.-X.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Q. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Sleeve Lobectomy for Centrally Located Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Mei, J.; Lin, F.; Pu, Q.; Ma, L.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, C.; Xia, L.; Liu, L. Comparison of the Short- and Long-term Outcomes of Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery versus Open Thoracotomy Bronchial Sleeve Lobectomy for Central Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Propensity Score Matched Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 4384–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, G.; She, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, G.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of thoracoscopic versus thoracotomy sleeve lobectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 5678–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Qin, Y.; Niu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Jiao, W. Robotic sleeve lobectomy for centrally located non–small cell lung cancer: A propensity score–weighted comparison with thoracoscopic and open surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 838–846.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rivas, D.; Garcia, A.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sekhniaidze, D.; Jiang, G.; Zhu, Y. Technical aspects of uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic double sleeve bronchovascular resections. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 58 (Suppl. 1), i14–i22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Meehan, D.; Lutfi, W.; Dhupar, R.; Christie, N.; Baker, N.; Schuchert, M.; Luketich, J.D.; Okusanya, O.T. Factors Associated With Survival in Complete Pathologic Response Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassorossi, C.; Filippo, L.; Pogliani., L.; Tabacco, D.; Iaffaldano, A.; Zanfrini, E.; Nachira, D.; Margaritora, S. Factors affect long-term survival in local-ly-advanced NSCLC-patients with pathological complete response after induction therapy followed by surgical resection? Clin. Lung Cancer 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayawake, H.; Okumura, N.; Yamanashi, K.; Takahashi, A.; Itasaka, S.; Yoshioka, H.; Nakashima, T.; Matsuoka, T. Non-small cell lung cancer with pathological complete response: Predictive factors and surgical outcomes. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 67, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katakami, N.; Tada, H.; Mitsudomi, T.; Kudoh, S.; Senba, H.; Matsui, K.; Saka, H.; Kurata, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Fukuoka, M. A phase 3 study of induction treatment with concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy before surgery in patients with pathologically confirmed N2 stage IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer (WJTOG9903). Cancer 2012, 118, 6126–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albain, K.S.; Swann, R.S.; Rusch, V.W.; Turrisi, A.T., III; Shepherd, F.A.; Smith, C.; Chen, Y.; Livingston, R.B.; Feins, R.H.; Gandara, D.R.; et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Chaft, J.; William, W.N.; Rusch, V.; Pisters, K.M.W.; Kalhor, N.; Pataer, A.; Travis, W.; Swisher, S.G.; Kris, M.G. Pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancers: Proposal for the use of major pathological response as a surrogate endpoint. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e42–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mouillet, G.; Monnet, E.; Milleron, B.; Puyraveau, M.; Quoix, E.; David, P.; Ducoloné, A.; Molinier, O.; Zalcman, G.; Depierre, A.; et al. Pathologic Complete Response to Preoperative Chemotherapy Predicts Cure in Early-Stage Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Combined Analysis of Two IFCT Randomized Trials. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Schil, P.E.; Yogeswaran, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lauwers, P.; Faivre-Finn, C. Advances in the use of surgery and multimodality treatment for N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2017, 17, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raman, V.; Jawitz, O.K.; Yang, C.-F.J.; Voigt, S.L.; Wang, H.; D’Amico, T.A.; Harpole, D.H.; Tong, B.C. Outcomes of surgery versus chemoradiotherapy in patients with clinical or pathologic stage N3 non–small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 158, 1680–1692.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-R.; Hou, X.; Li, D.-L.; Sai, K.; Dinglin, X.-X.; Chen, J.; Wang, N.; Li, M.-C.; Wang, K.-C.; Chen, L.-K. Management of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Initially Diagnosed With 1 to 3 Synchronous Brain-Only Metastases: A Retrospective Study. Clin. Lung Cancer 2021, 22, e25–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Hoang, C.D.; Kesarwala, A.; Schrump, D.S.; Guha, U.; Rajan, A. Role of Local Ablative Therapy in Patients with Oligometastatic and Oligoprogressive Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gomez, D.R.; Blumenschein, G.R.; Lee, J.J.; Hernández, M.; Ye, R.; Camidge, D.R.; Doebele, R.C.; Skoulidis, F.; Gaspar, L.E.; Gibbons, D.L.; et al. Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffioen, G.H.; Toguri, D.; Dahele, M.; Warner, A.; de Haan, P.F.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Slotman, B.; Yaremko, B.P.; Senan, S.; Palma, D.A. Radical treatment of synchronous oligometastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): Patient outcomes and prognostic factors. Lung Cancer 2013, 82, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Ohtaki, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Date, H.; Yamashita, M.; Iizasa, T.; Ito, H.; Yoshimura, K.; Okada, M.; Chida, M. Salvage surgery for non-small-cell lung cancer after definitive radiotherapy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanashi, K.; Hamaji, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Kishi, N.; Chen-Yoshikawa, T.F.; Mizowaki, T.; Date, H. Updated long-term outcomes of salvage surgery after stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 31, 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.C.; Ding, L.; Atay, S.M.; Nieva, J.J.; McFadden, P.M.; Chang, E.; Kim, A.W. Trimodality vs Chemoradiation and Salvage Resection in cN2 Stage IIIA Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 32, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, M.; Matthieu, S.; Benjamin, B.; Jean-Marc, B. Post-immunotherapy combined operative technique with an anterior surgical approach and robot-assisted lobectomy for an anterior superior sulcus tumor—Case report. J. Vis. Surg. 2020, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, E.D.; Sun, B.; Feng, L.; Verma, V.; Zhao, L.; Gomez, D.R.; Liao, Z.; Jeter, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Welsh, J.W.; et al. Association of Long-term Outcomes and Survival With Multidisciplinary Salvage Treatment for Local and Regional Recurrence After Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for Early-Stage Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e181390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamakawa, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Sakanoue, I.; Saito, T.; Date, N.; Tomii, K.; Katakami, N.; Imagunbai, T.; Kokubo, M. Salvage Pulmonary Operations Following Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Small Primary and Metastatic Lung Tumors: Evaluation of the Operative Procedures. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaji, M.; Chen-Yoshikawa, T.-F.; Matsuo, Y.; Motoyama, H.; Hijiya, K.; Menju, T.; Aoyama, A.; Sato, T.; Sonobe, M.; Date, H. Salvage video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for isolated local relapse after stereotactic body radiotherapy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer: Technical aspects and perioperative management. J. Vis. Surg. 2017, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dipper, A.; Jones, H.; Bhatnagar, R.; Preston, N.; Maskell, N.; Clive, A.O. Interventions for the management of malignant pleural effusions: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD010529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Couñago, F.; Luna, J.; Guerrero, L.L.; Vaquero, B.; Guillén-Sacoto, M.C.; González-Merino, T.; Taboada, B.; Díaz, V.; Rubio-Viqueira, B.; Díaz-Gavela, A.A.; et al. Management of oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients: Current controversies and future directions. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 10, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisi, D.; Barone, M.; Zaccagna, G.; Gabriele, F.; Crisci, R. Surgical approach in the oligometastatic patient. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brunelli, A.; Kim, A.W.; Berger, K.I.; Addrizzo-Harris, D.J. Physiologic Evaluation of the Patient With Lung Cancer Being Considered for Resectional Surgery Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2013, 143, e166S–e190S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boujibar, F.; Gravier, F.; Selim, J.; Baste, J. Preoperative assessment for minimally invasive lung surgery: Need an update? Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, L.; Marescaux, J. Patient-specific Surgical Simulation. World J. Surg. 2007, 32, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Zhu, X.; Jin, J.; Chen, Y.; Ying, H.; Chen, Y.; Lu, F.; Shen, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Comparison of the outcomes of sublobar resection and stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage T1-2N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer with tumor size ≤ 5 cm: A propensity score matching analysis. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 5934–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Eiken, P.; Blackmon, S. Image guided thermal ablation in lung cancer treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 7039–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaeys, T.; Berzenji, L.; Van Schil, P. Surgery after Induction Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Chaft, J.E.; Smith, K.N.; Anagnostou, V.; Cottrell, T.R.; Hellmann, M.D.; Zahurak, M.; Yang, S.C.; Jones, D.R.; Broderick, S.; et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.A.; Gainor, J.F.; Awad, M.M.; Chiuzan, C.; Grigg, C.M.; Pabani, A.; Garofano, R.F.; Stoopler, M.B.; Cheng, S.K.; White, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencio, M.; Nadal, E.; Insa, A.; García-Campelo, M.R.; Casal-Rubio, J.; Dómine, M.; Majem, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Martínez-Martí, A.; Carpeño, J.D.C.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nivolumab in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NADIM): An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, M.J.; Cools-Lartigue, J.; Tan, K.S.; Dycoco, J.; Bains, M.S.; Downey, R.J.; Huang, J.; Isbell, J.; Molena, D.; Park, B.J.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of Lung Resection After Immunotherapy for Metastatic or Unresectable Tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wislez, M.; Mazieres, J.; Lavole, A.; Zalcman, G.; Carre, O.; Egenod, T.; Caliandro, R.; Gervais, R.; Jeannin, G.; Molinier, O.; et al. 1214O Neoadjuvant durvalumab in resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Preliminary results from a multicenter study (IFCT-1601 IONESCO). Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, S794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Guo, Y.-J.; Song, J.; Wang, Y.-R.; Zhang, S.-L.; Huang, L.-T.; Zhao, J.-Z.; Jing, W.; Han, C.-B.; Ma, J.-T. Neoadjuvant EGFR-TKI Therapy for EGFR-Mutant NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Five Prospective Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Li, L.; Chen, T.; Fang, C. Effective Treatment of NSCLC with Surgery After Nivolumab Combined with Chemotherapy: A Case Report and Brief Review of the Literature. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 13307–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Chen, H.; Zeng, T.; Wu, W.; Xu, G.; Xu, C.; Zheng, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Chen, C. A pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy in a non-small cell lung cancer patient. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 2157–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Chaft, J.E. Immunotherapy in surgically resectable non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S404–S411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamdi, Y.; Abdeljaoued-Tej, I.; Zatchi, A.A.; Abdelhak, S.; Boubaker, S.; Brown, J.S.; Benkahla, A. Cancer in Africa: The Untold Story. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health C on CC in LM-IC on G. In Cancer Control Opportunities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; Sloan, F.A.; Gelband, H. (Eds.) The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sayani, A.; Vahabi, M.; O’Brien, M.A.; Liu, G.; Hwang, S.W.; Selby, P.; Nicholson, E.; Lofters, A. Perspectives of family physicians towards access to lung cancer screening for individuals living with low income—A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pr. 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medbery, R.L.; Fernandez, F.G.; Kosinski, A.S.; Tong, B.C.; Furnary, A.P.; Feng, L.; Onaitis, M.; Boffa, D.; Wright, C.D.; Cowper, P.; et al. Costs Associated with Lobectomy for Lung Cancer: A novel analysis merging STS and Medicare data. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 111, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J. Cost concerns for robotic thoracic surgery. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 1, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gac, C.; Gondé, H.; Gillibert, A.; Laurent, M.; Selim, J.; Bottet, B.; Varin, R.; Baste, J.-M. Medico-economic impact of robot-assisted lung segmentectomy: What is the cost of the learning curve? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 30, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J.M.; Goodwin, M.; Kneuertz, P.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.; Merritt, R.E.; D’Souza, D.M. Robotic lobectomy costs and quality of life. Mini-Invasive Surg. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Jalbert, J.; Isaacs, A.; Altorki, N.K.; Isom, O.W.; Sedrakyan, A. Comparative Effectiveness of Robotic-Assisted vs Thoracoscopic Lobectomy. Chest 2014, 146, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Perentes, J.Y.; Doucet, V.; Zellweger, M.; Marcucci, C.; Ris, H.-B.; Krueger, T.; Gronchi, F. An enhanced recovery after surgery program for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery anatomical lung resections is cost-effective. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 5879–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.; Kronborg, C.; Jørgensen, O.D.; Andersen, C.; Licht, P.B. Cost–utility analysis of minimally invasive surgery for lung cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 56, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazieh, A.R.; Onal, H.C.; Tan, D.S.W.; Soo, R.A.; Prabhash, K.; Kumar, A.; Huggenberger, R.; Robb, S.; Byoung-Chul, C. Real-world treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Results of KINDLE, a multi-country observational study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göker, E.; Altwairgi, A.; Al-Omair, A.; Tfayli, A.; Black, E.; Elsayed, H.; Selek, U.; Koegelenberg, C. Multi-disciplinary approach for the management of non-metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in the Middle East and Africa: Expert panel recommendations. Lung Cancer 2021, 158, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montagne, F.; Guisier, F.; Venissac, N.; Baste, J.-M. The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art. Cancers 2021, 13, 3711. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153711

Montagne F, Guisier F, Venissac N, Baste J-M. The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art. Cancers. 2021; 13(15):3711. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153711

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontagne, François, Florian Guisier, Nicolas Venissac, and Jean-Marc Baste. 2021. "The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art" Cancers 13, no. 15: 3711. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153711

APA StyleMontagne, F., Guisier, F., Venissac, N., & Baste, J.-M. (2021). The Role of Surgery in Lung Cancer Treatment: Present Indications and Future Perspectives—State of the Art. Cancers, 13(15), 3711. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153711