Immune-Stimulatory Effects of Curcumin on the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

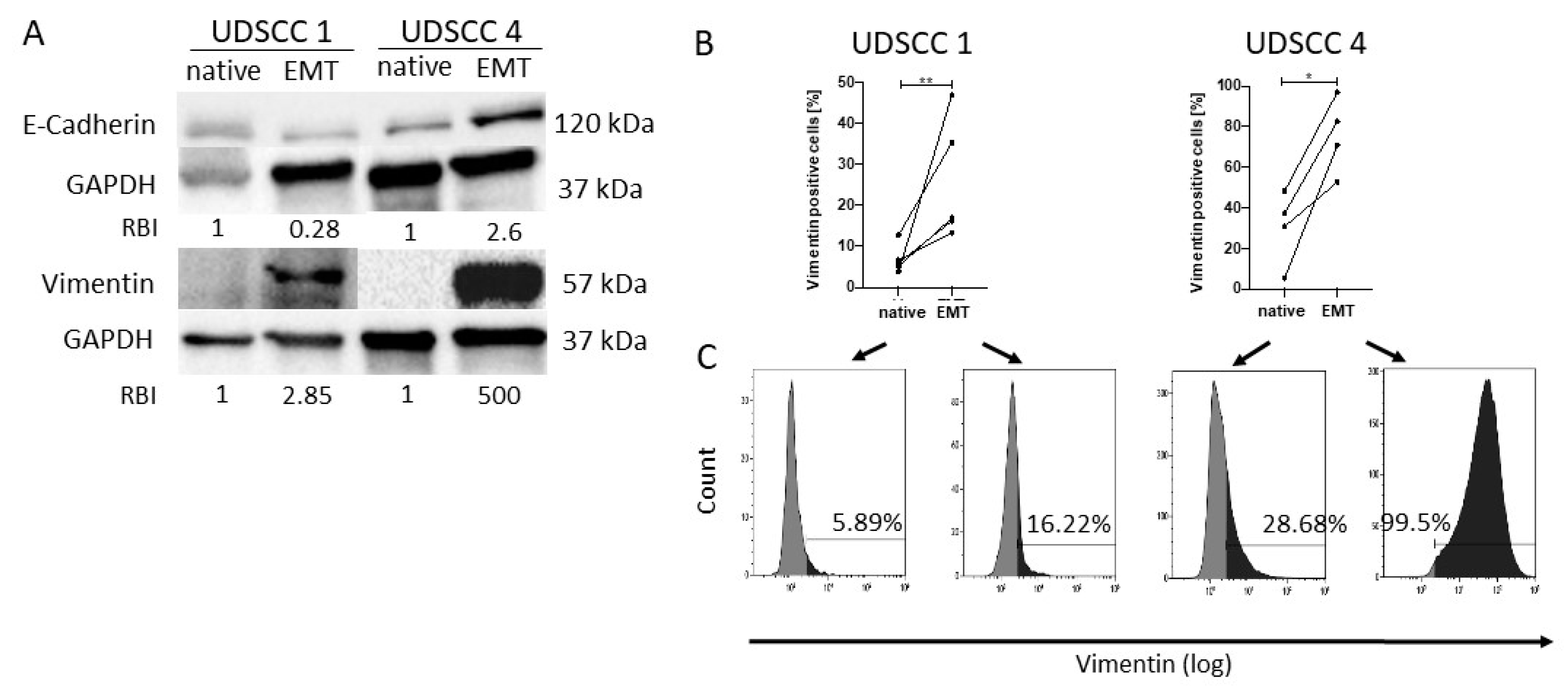

2.1. Confirmation of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition In Vitro

2.2. Curcumin-Dependent Reversion of EMT

2.3. The Effect of Curcumin on Chemokine Expression in Ex Vivo Tumor Tissues

2.4. Effects of Curcumin on Chemokine Expression in Macrophage Cultures

2.5. Curcumin Inhibits the Migratory Potential of Treg

2.6. The Effect of Curcumin on NF-κB Inhibition

2.7. NF-κB Inhibition by Curcumin Is More Potent Than Inhibition by BAY or CAPE

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

4.1.1. Induction of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

4.1.2. Incubation with Curcumin

4.2. Patients

Clinicopathological Characteristics of HNSCC Patients

4.3. Ex Vivo Tumor Tissue Explant Culture System

4.4. Annexin/PI Apoptosis Assay

4.5. Generation of Macrophages

Incubation of Macrophages

4.6. Western Blot

4.7. Flow Cytometry

4.8. ELISA

4.9. NF-κB ELISA

4.10. mRNA Isolation

4.11. cDNA Synthesis and RT qPCR

4.12. Migration Assay

4.13. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| Annexin/PI | annexin/propidium iodide |

| CAPE | caffeic acid phenethyl ester |

| CTL | cytotoxic T-cell |

| COX2 | cyclooxygenase 2 |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| EMT | epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| GM-CSF | granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HNSCC | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IDOI | indolamin-2,3-dioxygenase |

| κBα | NFκB inhibitor, alpha |

| MDSC | myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| MET | mesenchymal to epithelial transition |

| NFκB | nuclear factor kappa of activated B-cells |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PIC | polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid |

| pIκBα | phosphorylated nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha |

| RT | room temperature |

| Treg | regulatory T-cells |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TRL3 | toll-like receptor 3 |

| UDSCC | University of Düsseldorf squamous cell carcinoma |

| UICC | Union for International Cancer Control |

Appendix A

| Primer Names | Primer Sequences | Manufacturer |

| Vimentin—For | 5′- GAGAACTTTGCCGTTGAAGC-3′ | Biomers |

| Vimentin—Rev | 5′- GCTTCCTGTAGGTGGCAATC-3′ | Biomers |

| SNAIL—For | 5′- TCGGAAGCCTAACTACAGCGA-3′ | Biomers |

| SNAIL—Rev | 5′- AGATGAGCATTGGCAGCGAG-3′ | Biomers |

| TWIST—For | 5′- GGAGTCCGCAGTCTTACGAG-3′ | Biomers |

| TWIST—Rev | 5′- TCTGGAGGACCTGGTAGAGG-3′ | Biomers |

| Primer Names | Unique Assay ID | Manufacturer |

| CCL5 | qHsaCID0011644 | Bio Rad |

| CXCL10 | qHsaCED0046619 | Bio Rad |

| CCL22 | qHsaCID0015408 | Bio Rad |

References

- Stewart, B.W.; Wild, C.P. World Cancer Report 2014; IARC Publications Website-World Cancer Report 2014; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whiteside, T.L. Head and Neck Carcinoma Immunotherapy: Facts and Hopes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 24, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ang, K.K.; Zhang, Q.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tan, P.F.; Sherman, E.J.; Weber, R.S.; Galvin, J.M.; Bonner, J.A.; Harris, J.; El-Naggar, A.K.; et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Concurrent Accelerated Radiation Plus Cisplatin with or Without Cetuximab for Stage III to IV Head and Neck Carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2940–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L. Immunology and Immunotherapy of Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamarneh, O.; Amarnath, S.M.P.; Stafford, N.D.; Greenman, J. Regulatory T cells: What role do they play in antitumor immunity in patients with head and neck cancer? Head Neck 2008, 30, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H.F.; Weaver, V.M.; Tlsty, T.D.; Bergers, G. Tumor microenvironment and progression. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 103, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moody, R.; Wilson, K.; Jaworowski, A.; Plebanski, M. Natural Compounds with Potential to Modulate Cancer Therapies and Self-Reactive Immune Cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Facciabene, A.; Motz, G.T.; Coukos, G. T-Regulatory Cells: Key Players in Tumor Immune Escape and Angiogenesis: Figure 1. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chikamatsu, K.; Sakakura, K.; Whiteside, T.L.; Furuya, N. Relationships between regulatory T cells and CD8+ effector populations in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2007, 29, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, T.J.; Coukos, G.; Zou, L.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Evdemon-Hogan, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Burow, M.; et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlecnik, B.; Tosolini, M.; Charoentong, P.; Kirilovsky, A.; Bindea, G.; Berger, A.; Camus, M.; Gillard, M.; Bruneval, P.; Fridman, W.; et al. Biomolecular Network Reconstruction Identifies T-Cell Homing Factors Associated with Survival in Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumwalt, T.J.; Arnold, M.; Goel, A.; Boland, C.R. Active secretion of CXCL10 and CCL5 from colorectal cancer microenvironments associates with GranzymeB+ CD8+ T-cell infiltration. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 2981–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qian, B.-Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage Diversity Enhances Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evrard, D.; Szturz, P.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Astorgues-Xerri, L.; Abitbol, C.; Paradis, V.; Raymond, E.; Albert, S.; Barry, B.; Faivre, S. Macrophages in the microenvironment of head and neck cancer: Potential targets for cancer therapy. Oral Oncol. 2019, 88, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.T.; Knops, A.; Swendseid, B.; Martinez-Outschoom, U.; Harshyne, L.; Philp, N.; Rodeck, U.; Luginbuhl, A.; Cognetti, D.; Johnson, J.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Tumor-Associated Macrophage Content in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utispan, K.; Koontongkaew, S. Fibroblasts and macrophages: Key players in the head and neck cancer microenvironment. J. Oral Biosci. 2017, 59, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Carrasco, L.; Majano, P.; Sánchez-Toméro, J.A.; Selgas, R.; López-Cabrera, M.; Aguilera, A.; Mateo, G.G. Natural Plants Compounds as Modulators of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bahrami, A.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin: A potent agent to reverse epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell. Oncol. 2019, 42, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.; Zanotto, M.; Malpeli, G.; Bassi, G.; Perbellini, O.; Chilosi, M.; Bifari, F.; Krampera, M. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) induced by inflammatory priming elicits mesenchymal stromal cell-like immune-modulatory properties in cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgi, B.; De Souza, F.C.; Lima, I.M.D.S.; Schiavinato, J.L.D.S.; Corveloni, A.C.; Thomé, C.H.; Silva, W.J.A.; Faça, V.M.; Covas, D.T.; Zago, M.A.; et al. A High-Content Screening Approach to Identify MicroRNAs against Head and Neck Cancer Cell Survival and EMT in an Inflammatory Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter Van Waes. Nuclear Factor-κB in Development, Prevention, and Therapy of Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karin, M.; Greten, F.R. NF-κB: Linking Inflammation and Immunity to Cancer Development and Progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, V.; Sahebkar, A.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and its major constituent (curcumin) as nontoxic and safe substances: Review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Tyagi, A.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, a component of golden spice: From bedside to bench and back. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Charlet, J.; Juncker, T.; Teiten, M.-H.; Dicato, M.; Diederich, M. Effect of Curcumin on Nuclear Factor κB Signaling Pathways in Human Chronic Myelogenous K562 Leukemia Cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1171, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. TNF-A/NF-κB/Snail Pathway in Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, C.; Pries, R.; Wollenberg, B. Established and Novel NF-κB Inhibitors Lead to Downregulation of TLR3 and the Proliferation and Cytokine Secretion in HNSCC. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, M.; Yerneni, S.; Sarkar, S.N.; Orr, B.; Muthuswamy, R.; Voyten, J.; Modugno, F.; Jiang, W.; Grimm, M.; Basse, P.H.; et al. Helicase-Driven Activation of NFκB-COX2 Pathway Mediates the Immunosuppressive Component of dsRNA-Driven Inflammation in the Human Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4292–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ridnour, L.A.; Cheng, R.Y.; Switzer, C.H.; Heinecke, J.L.; Ambs, S.; Glynn, S.; Young, H.A.; Trinchieri, G.; Wink, D.A. Molecular Pathways: Toll-like Receptors in the Tumor Microenvironment—Poor Prognosis or New Therapeutic Opportunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iribarren, K.; Bloy, N.; Buqué, A.; Cremer, I.; Eggermont, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Fucikova, J.; Galon, J.; Špíšek, R.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. Trial Watch: Immunostimulation with Toll-like receptor agonists in cancer therapy. OncoImmunology 2015, 5, e1088631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ammi, R.; De Waele, J.; Willemen, Y.; Van Brussel, I.; Schrijvers, D.M.; Lion, E.; Smits, E.L. Poly(I:C) as cancer vaccine adjuvant: Knocking on the door of medical breakthroughs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 146, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, M.; Yee, K.; Permezel, M.; Rice, G.E. Sulfasalazine and BAY 11-7082 Interfere with the Nuclear Factor-κB and IκB Kinase Pathway to Regulate the Release of Proinflammatory Cytokines from Human Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle in Vitro. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, W.; Wu, T.; Lu, R.; Shi, B. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Proinflammatory Responses in Human Gingival Fibroblasts via NF-κB and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 794, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, P.G.; Moreno-bueno, G.; Portillo, F.; Cano, A. EMT: Present and Future in Clinical Oncology. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 718–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dutot, M.; Grassin-Delyle, S.; Salvator, H.; Brollo, M.; Rat, P.; Fagon, R.; Naline, E.; DeVillier, P. A marine-sourced fucoidan solution inhibits Toll-like-receptor-3-induced cytokine release by human bronchial epithelial cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uematsu, S.; Akira, S. Toll-like Receptors and Type I Interferons. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 15319–15323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasani, B.; Navabi, H.; Adams, M. Ampligen: A potential toll-like 3 receptor adjuvant for immunotherapy of cancer. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3401–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.M.; Nicodemus, C.F.; Carter, W.A.; Horvath, J.C.; Strayer, D.R. Discordant biological and toxicological species responses to TLR3 activation. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, N.; Sutton, J.M.; Hoehn, R.S.; Jernigan, P.L.; Friend, L.A.; Johanningman, T.A.; Schuster, R.M.; Lentsch, A.B.; Caldwell, C.C.; Pritts, T.A. IFNγ and TNFα mediate CCL22/MDC production in alveolar macrophages after hemorrhage and resuscitation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2020, 318, L864–L872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guan, X.; Ma, X. Interferon Regulatory Factor 1 Is an Essential and Direct Transcriptional Activator for Interferon γ-induced RANTES/CCl5 Expression in Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24347–24355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mach, F.; Sauty, A.; Iarossi, A.S.; Sukhova, G.K.; Neote, K.; Libby, P.; Luster, A.D. Differential expression of three T lymphocyte-activating CXC chemokines by human atheroma-associated cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 104, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zitvogel, L.; Tesniere, A.; Kroemer, G. Cancer despite immunosurveillance: Immunoselection and immunosubversion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvaro, T. Outcome in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma can be Predicted from the Presence of Accompanying Cytotoxic and Regulatory T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berger, N.; Ben Bassat, H.; Klein, B.Y.; Laskov, R. Cytotoxicity of NF-κB Inhibitors Bay 11-7085 and Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester to Ramos and Other Human B-Lymphoma Cell Lines. Exp. Hematol. 2007, 35, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.H.; Paek, H.; Li, M.; Ban, Y.; Karaga, M.K.; Shashidharamurthy, R.; Wang, X. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester exerts apoptotic and oxidative stress on human multiple myeloma cells. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 37, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, C. BAY-11-7082 Induces Apoptosis of Multiple Myeloma U266 Cells through Inhibiting NF-κB Pathway. Eur. Rev. Med Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, F.; Dusemund, B.; Galtier, P.; Gilbert, J.; Gott, D.M.; Grilli, S.; Gürtler, R.; König, J.; Lambré, C.; J-C, L.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Curcumin (E 100) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1679. [Google Scholar]

- Lao, C.D.; RuffinIV, M.T.; Normolle, D.; Heath, D.D.; Murray, S.I.; Bailey, J.M.; E Boggs, M.; Crowell, J.; Rock, C.L.; E Brenner, D. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boozari, M.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Impact of curcumin on toll-like receptors. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 12471–12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.L.; Hsu, C.H.; Lin, J.K.; Hsu, M.M.; Ho, Y.F.; Shen, T.S.; Ko, J.Y.; Lin, J.T.; Lin, B.R.; Ming-Shiang, W.; et al. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Takada, Y.; Singh, S.; Myers, J.N.; Aggarwal, B.B. Inhibition of Growth and Survival of Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells by Curcumin Via Modulation of Nuclear factor-κB Signaling. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 111, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, B.; Ekshyyan, O.; Nathan, N.; Moore-Medlin, T.; Rong, X.; Ma, X.; Khandelwal, A.; Christy, H.T.; Abreo, F.; McClure, G.; et al. Enhanced Systemic Bioavailability of Curcumin Through Transmucosal Administration of a Novel Microgranular Formulation. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 6411–6418. [Google Scholar]

- Bayet-Robert, M.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Leheurteur, M.; Gachon, F.; Planchat, E.; Abrial, C.; Mouret-Reynier, M.-A.; Durando, X.; Barthomeuf, C.; Chollet, P. Phase I dose escalation trial of docetaxel plus curcumin in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhillon, N.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Newman, R.A.; Wolff, R.A.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; Ng, C.S.; Badmaev, V.; Kurzrock, R. Phase II Trial of Curcumin in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrington, B.S.; Annunziata, C.M. NF-κB Signaling in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olivera, A.; Moore, T.W.; Hu, F.; Brown, A.P.; Sun, A.; Liotta, D.C.; Snyder, J.P.; Yoon, Y.; Shim, H.; Marcus, A.I.; et al. Inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway by the curcumin analog, 3,5-Bis(2-pyridinylmethylidene)-4-piperidone (EF31): Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 12, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marquardt, J.U.; Gomez-Quiroz, L.; Camacho, L.O.A.; Pinna, F.; Lee, Y.; Kitade, M.; Domínguez, M.P.; Castven, D.; Breuhahn, K.; Conner, E.A.; et al. Curcumin Effectively Inhibits Oncogenic NF-kB Signaling and Restrains Stemness Features in Liver Cancer. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muthuswamy, R.; Wang, L.; Pitteroff, J.; Gingrich, J.R.; Kalinski, P. Combination of IFNα and poly-I:C reprograms bladder cancer microenvironment for enhanced CTL attraction. J. Immunother. Cancer 2015, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schuler, P.J.; Harasymczuk, M.; Schilling, B.; Lang, S.; Whiteside, T.L. Separation of human CD4+CD39+ T cells by magnetic beads reveals two phenotypically and functionally different subsets. J. Immunol. Methods 2011, 369, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theodoraki, M.-N.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Jackson, E.K.; Whiteside, T.L. Exosomes in HNSCC plasma as surrogate markers of tumour progression and immune competence. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 194, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age | ||

| ≥65 | 7 | 77 |

| ≤65 | 2 | 23 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 89 |

| Female | 1 | 11 |

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Oral cavity | 2 | 22 |

| Pharynx | 4 | 45 |

| Larynx | 3 | 33 |

| Tumor stage | ||

| T1 | 1 | 11 |

| T2 | 1 | 11 |

| T3 | 6 | 67 |

| T4 | 1 | 11 |

| Nodal status | ||

| N0 | 1 | 11 |

| N+ | 8 | 89 |

| Distant metastasis | ||

| M0 | 9 | 100 |

| UICC stage | ||

| I/II | 4 | 45 |

| III/IV | 5 | 55 |

| HPV status | ||

| (p16 +/HPV-DNA+) | ||

| Positive | 1 | 11 |

| Negative | 3 | 33 |

| Undefined | 5 | 55 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Yes | 8 | 89 |

| No | 1 | 11 |

| Tobacco consumption | ||

| Yes | 5 | 55 |

| No | 4 | 45 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kötting, C.; Hofmann, L.; Lotfi, R.; Engelhardt, D.; Laban, S.; Schuler, P.J.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Brunner, C.; Theodoraki, M.-N. Immune-Stimulatory Effects of Curcumin on the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061335

Kötting C, Hofmann L, Lotfi R, Engelhardt D, Laban S, Schuler PJ, Hoffmann TK, Brunner C, Theodoraki M-N. Immune-Stimulatory Effects of Curcumin on the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2021; 13(6):1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061335

Chicago/Turabian StyleKötting, Charlotte, Linda Hofmann, Ramin Lotfi, Daphne Engelhardt, Simon Laban, Patrick J. Schuler, Thomas K. Hoffmann, Cornelia Brunner, and Marie-Nicole Theodoraki. 2021. "Immune-Stimulatory Effects of Curcumin on the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Cancers 13, no. 6: 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061335

APA StyleKötting, C., Hofmann, L., Lotfi, R., Engelhardt, D., Laban, S., Schuler, P. J., Hoffmann, T. K., Brunner, C., & Theodoraki, M. -N. (2021). Immune-Stimulatory Effects of Curcumin on the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers, 13(6), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061335