Population-Based Assessment of Determining Predictors for Discharge Disposition in Patients with Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Cohort and Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

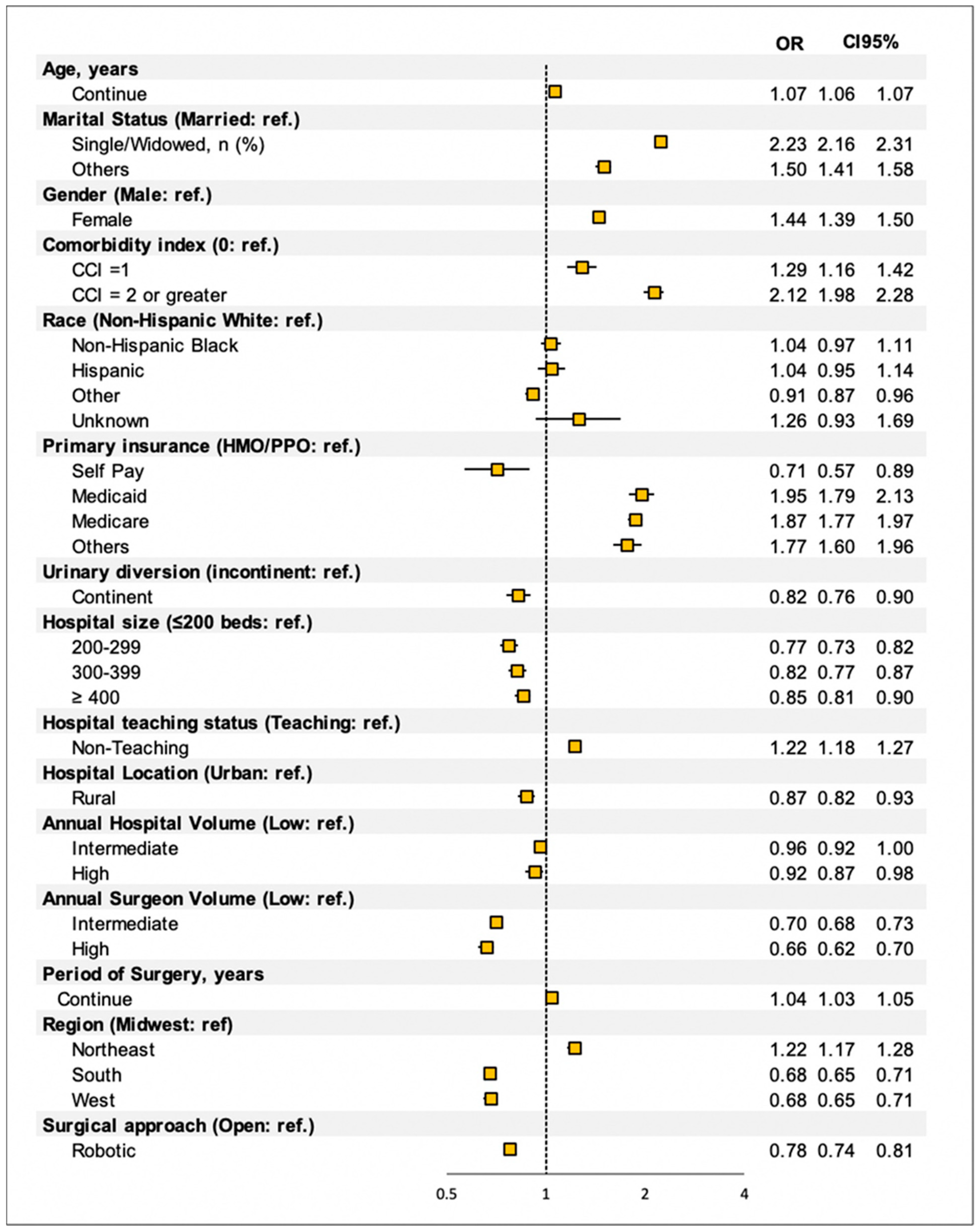

3.2. Predictor of Discharge Disposition after RC

3.3. Surgical Volumes-Based Analysis

3.4. Geographic Area Analysis

3.4.1. Midwest

3.4.2. Northeast

3.4.3. South

3.4.4. West

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Discharge home with/without home healthcare | DISC HOME W/HOME HEALTH PLAN ACUT IP RDM |

| DISCH HOME/SELF PLANNED ACUTE IP READM | |

| DISCHARGED TO HOME HEALTH ORG. | |

| DISCHARGED TO HOME IV PROVIDER | |

| DISCHARGED TO HOME OR SELF CARE | |

| Continue Rehabilitation Centers (CFRs) | DIS/TRAN FACLTY UNLISTD PLAN ACUT IP RDM |

| DIS/TRAN MEDC SWING BED PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DIS/TRAN NURSNG MEDCAID PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DIS/TRAN PSYCH HOS/DPU PLAN ACUTE IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRAN CUST/SUPP FAC PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRAN DESIG DISASTR PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRAN SHRT TERM HOS PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRAN SNF MEDICARE PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRANS CANCER/CHILD PLAN ACUT IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRANS FEDERAL FAC PLAN ACUTE IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRANS IRF/REH DPU PLAN ACUTE IP RDM | |

| DISC/TRANS MEDICR LTCH PLAN ACUTE IP RDM | |

| DISCH/TRANS CAH PLAN ACUTE IP READM | |

| DISCHARGED TO HOSPICE-HOME | |

| DISCHARGED TO HOSPICE-MEDICAL FACILITY | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO A CAH | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO FEDERAL HOSP | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO ICF | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO OTHER FACILITY | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO PSYCH HOSP | |

| DISCHARGED/TRANSFERRED TO SNF | |

| DISCHGRD TO THIS INSTITUTION FOR OP SVCS | |

| DISCHRGD/TRANSFRD TO SWING BED | |

| DISCHRGD/TRNSFRD TO A NURSING FACILITY M | |

| DSCHRD/XFERED CANCER CTR/CHILDRN HOSP | |

| DSCHRD/XFERED OTH HLTH INST NOT IN LIST | |

| DSCHRGD TO OTHER INSTITUTION FOR OP SVCS | |

| DSCHRGD/TRNSFRD TO A LTC HOSPITAL | |

| DSCHRGD/TRNSFRD TO ANOTHER REHAB FACILTY |

Appendix B

| ICD VERSION | ICD CODE | ICD DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 17.44 | ENDOSCOPIC ROBOTIC ASSISTED PROC |

| 9 | 56.51 | FORM CUTANEOUS URETERO-ILEOSTOMY |

| 9 | 56.61 | FORM CUTANEOUS URETEROSTOMY NEC |

| 9 | 45.00 | INTESTINAL INCISION NOS |

| 9 | 45.50 | INTESTINAL SEGMENT ISOLATION NOS |

| 9 | 17.42 | LAP ROBOTIC ASSISTED PROCEDURE |

| 9 | 54.21 | LAPAROSCOPY |

| 9 | 56.95 | LIGATION OF URETER |

| 9 | 17.41 | OPEN ROBOTIC ASSISTED PROCEDURE |

| 9 | 56.34 | OPEN URETERAL BIOPSY |

| 9 | 45.71 | OPEN/OTHR MULT SEGMT LG BOWEL RESEC |

| 9 | 17.49 | OTHR/UNSPEC ROBOTIC ASSISTED PROC |

| 9 | 45.62 | PARTIAL RESECTION SMALL BOWEL NEC |

| 9 | 46.23 | PERMANENT ILEOSTOMY NEC |

| 9 | 57.71 | RADICAL CYSTECTOMY |

| 9 | 40.53 | RADICAL EXCISE ILIAC LYMPH NODES |

| 9 | 40.59 | RADICAL LYMPH NODE EXCISION NEC |

| 9 | 40.50 | RADICAL LYMPH NODE EXCISION NOS |

| 9 | 60.5 | RADICAL PROSTATECTOMY |

| 9 | 68.7 | RADICAL VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY |

| 9 | 68.79 | RADICAL VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY NOS |

| 9 | 71.5 | RADICAL VULVECTOMY |

| 9 | 66.51 | REMOVE BOTH FALLOPIAN TUBES |

| 9 | 45.91 | SM-TO-SM INTESTINAL ANASTOMOSIS |

| 9 | 46.81 | SMALL INTESTINE MANIPULATION |

| 9 | 45.51 | SMALL INTESTINE SEGMENT ISOLATION |

| 9 | 68.4 | TOTAL ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY |

| 9 | 68.49 | TOTAL ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY NOS |

| 9 | 57.79 | TOTAL CYSTECTOMY NEC |

| 9 | 56.99 | URETERAL OPERATIONS NEC |

| 9 | 56.40 | URETERECTOMY NOS |

| 9 | 56.74 | URETERONEOCYSTOSTOMY |

| 9 | 57.87 | URINARY BLADDER RECONSTRUCTION |

| 9 | 56.71 | URINARY DIVERSION TO INTESTINE |

| 10 | 0T1807B | BP BIL URETERS TO BLADDER W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T18079 | BP BIL URETERS TO COLOCUT W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T18479 | BP BIL URETERS TO COLOCUT W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180Z9 | BP BIL URETERS TO COLOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T184Z9 | BP BIL URETERS TO COLOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T18478 | BP BIL URETERS TO COLON W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1807D | BP BIL URETERS TO CUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1847D | BP BIL URETERS TO CUTANE W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180JD | BP BIL URETERS TO CUTANEOUS W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T183JD | BP BIL URETERS TO CUTANEOUS W/SS,PA |

| 10 | 0T1807C | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEOCUT W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1847C | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEOCUT W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T184JC | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEOCUT W/SS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180ZC | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T184ZC | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T184JA | BP BIL URETERS TO ILEUM W/SS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180JB | BP BILAT URETERS TO BLADDER W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T180J9 | BP BILAT URETERS TO COLOCUT W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T180J8 | BP BILAT URETERS TO COLON W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T180JC | BP BILAT URETERS TO ILEOCUT W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1807A | BP BILAT URETERS TO ILEUM W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1847A | BP BILAT URETERS TO ILEUM W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180JA | BP BILAT URETERS TO ILEUM W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T18078 | BP BILTRL URETERS TO COLON W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B079 | BP BLADDER TO COLOCUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B479 | BP BLADDER TO COLOCUTANE W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1B0Z9 | BP BLADDER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B4Z9 | BP BLADDER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1B07D | BP BLADDER TO CUTANEOUS W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B07C | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B47C | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANE W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1B0KC | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANE W/NATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B0JC | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANE W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B4JC | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANE W/SS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1B0ZC | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1B4ZC | BP BLADDER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T170ZD | BP LEFT URETER TO CUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T170ZC | BP LEFT URETER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T170Z9 | BP LT URETER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T174Z9 | BP LT URETER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1707D | BP LT URETER TO CUTANEOUS W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T170JD | BP LT URETER TO CUTANEOUS W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1747C | BP LT URETER TO ILEOCUT W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1707C | BP LT URETER TO ILEOCUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T170JC | BP LT URETER TO ILEOCUTANE W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T174ZC | BP LT URETER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1707A | BP LT URETER TO ILEUM W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T1747A | BP LT URETER TO ILEUM W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T170JA | BP LT URETER TO ILEUM W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T16079 | BP RT URETER TO COLOCUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T160Z9 | BP RT URETER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T164Z9 | BP RT URETER TO COLOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T164Z8 | BP RT URETER TO COLON,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1607D | BP RT URETER TO CUTANEOUS W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T164JD | BP RT URETER TO CUTANEOUS W/SS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T164ZD | BP RT URETER TO CUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1647C | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUT W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1607C | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUTANE W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T160JC | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUTANE W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T164JC | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUTANE W/SS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T160ZC | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T164ZC | BP RT URETER TO ILEOCUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1607A | BP RT URETER TO ILEUM W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0T164ZA | BP RT URETER TO ILEUM,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180ZD | BYPASS BIL URETERS TO CUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T184ZD | BYPASS BIL URETERS TO CUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180ZB | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO BLADDER,OA |

| 10 | 0T184ZB | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO BLADDER,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180Z8 | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO COLON,OA |

| 10 | 0T184Z8 | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO COLON,PEA |

| 10 | 0T180ZA | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO ILEUM,OA |

| 10 | 0T184ZA | BYPASS BILAT URETERS TO ILEUM,PEA |

| 10 | 0T1B4ZD | BYPASS BLADDER TO CUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T170ZB | BYPASS LEFT URETER TO BLADDER,OA |

| 10 | 0T170ZA | BYPASS LEFT URETER TO ILEUM,OA |

| 10 | 0T170Z8 | BYPASS LT URETER TO COLON,OA |

| 10 | 0T174Z8 | BYPASS LT URETER TO COLON,PEA |

| 10 | 0T174ZD | BYPASS LT URETER TO CUTANEOUS,PEA |

| 10 | 0T174ZA | BYPASS LT URETER TO ILEUM,PEA |

| 10 | 0T160ZB | BYPASS RT URETER TO BLADDER,OA |

| 10 | 0T160J8 | BYPASS RT URETER TO COLON W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0T160Z8 | BYPASS RT URETER TO COLON,OA |

| 10 | 0T160ZD | BYPASS RT URETER TO CUTANEOUS,OA |

| 10 | 0T160ZA | BYPASS RT URETER TO ILEUM,OA |

| 10 | 0TB70ZZ | EXCISION LT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TB73ZX | EXCISION LT URETER,PA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB74ZX | EXCISION LT URETER,PEA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB78ZZ | EXCISION LT URETER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TB78ZX | EXCISION LT URETER,VN OR AOE,DIAG |

| 10 | 0TBB0ZX | EXCISION OF BLADDER,OA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBB0ZZ | EXCISION OF BLADDER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TBB3ZX | EXCISION OF BLADDER,PA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBB4ZX | EXCISION OF BLADDER,PEA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBB7ZZ | EXCISION OF BLADDER,VN OR AO |

| 10 | 0TBB7ZX | EXCISION OF BLADDER,VN OR AO,DIAG |

| 10 | 0TBB8ZZ | EXCISION OF BLADDER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TBB8ZX | EXCISION OF BLADDER,VN OR AOE,DIAG |

| 10 | 0DBB8ZZ | EXCISION OF ILEUM NAT/AOE |

| 10 | 0DBB0ZZ | EXCISION OF ILEUM, OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TB70ZX | EXCISION OF LT URETER,OA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB74ZZ | EXCISION OF LT URETER,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TB77ZX | EXCISION OF LT URETER,VN OR AO,DIAG |

| 10 | 07BC0ZZ | EXCISION OF PELVIS LYMPHATIC,OA |

| 10 | 07BC3ZZ | EXCISION OF PELVIS LYMPHATIC,PA |

| 10 | 07BC4ZZ | EXCISION OF PELVIS LYMPHATIC,PEA |

| 10 | 0TB68ZZ | EXCISION OF RT URETER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TBD0ZX | EXCISION OF URETHRA,OA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBD0ZZ | EXCISION OF URETHRA,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TBD3ZX | EXCISION OF URETHRA,PA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBD4ZX | EXCISION OF URETHRA,PEA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TBD4ZZ | EXCISION OF URETHRA,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TBD7ZZ | EXCISION OF URETHRA,VN OR AO |

| 10 | 0TBD8ZZ | EXCISION OF URETHRA,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TBD8ZX | EXCISION OF URETHRA,VN OR AOE,DIAG |

| 10 | 0TB60ZX | EXCISION RT URETER,OA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB60ZZ | EXCISION RT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TB63ZX | EXCISION RT URETER,PA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB64ZX | EXCISION RT URETER,PEA,DIAGNOSTIC |

| 10 | 0TB64ZZ | EXCISION RT URETER,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TB67ZX | EXCISION RT URETER,VN OR AO,DIAG |

| 10 | 0TB68ZX | EXCISION RT URETER,VN OR AOE,DIAG |

| 10 | 0DB80ZZ | EXCISION SMALL INTESTINE OPEN APPRO |

| 10 | 0DB84ZZ | EXCISION SMALL INTESTINE PEA |

| 10 | 0DB83ZZ | EXCISION SMALL INTESTINE PERCU APPR |

| 10 | 0TCB0ZZ | EXTIRPATION OF MATTER BLADDER,OA |

| 10 | 0TCB4ZZ | EXTIRPATION OF MATTER BLADDER,PEA |

| 10 | 0TNB0ZZ | RELEASE BLADDER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TNB4ZZ | RELEASE BLADDER,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0DNB0ZZ | RELEASE ILEUM, OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0DNB4ZZ | RELEASE ILEUM,PERCU ENDO APPR |

| 10 | 0DN84ZZ | RELEASE SMALL INTESTINE, PEA |

| 10 | 0DN80ZZ | RELEASE SMALL INTESTINE,OPEN APPR |

| 10 | 0TND4ZZ | RELEASE URETHRA,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TND7ZZ | RELEASE URETHRA,VN OR AO |

| 10 | 0TND8ZZ | RELEASE URETHRA,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TRB07Z | REPLACEMENT OF BLADDER W/ATS,OA |

| 10 | 0TRB47Z | REPLACEMENT OF BLADDER W/ATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0TRB0KZ | REPLACEMENT OF BLADDER W/NATS,OA |

| 10 | 0TRB4KZ | REPLACEMENT OF BLADDER W/NATS,PEA |

| 10 | 0TRB0JZ | REPLACEMENT OF BLADDER W/SS,OA |

| 10 | 0TS80ZZ | REPOSITION BILATERAL URETERS,OA |

| 10 | 0TSC0ZZ | REPOSITION BLADDER NECK,OA |

| 10 | 0TSC4ZZ | REPOSITION BLADDER NECK,PEA |

| 10 | 0TSB0ZZ | REPOSITION BLADDER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TS70ZZ | REPOSITION LT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TS74ZZ | REPOSITION LT URETER,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TS60ZZ | REPOSITION RT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0DS80ZZ | REPOSITION SMALL INTESTINE,OA |

| 10 | 0TSD0ZZ | REPOSITION URETHRA,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TT70ZZ | RESECTION LT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TTC0ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER NECK,OA |

| 10 | 0TTC4ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER NECK,PEA |

| 10 | 0TTC8ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER NECK,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TTB0ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TTB4ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TTB7ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER,VN OR AO |

| 10 | 0TTB8ZZ | RESECTION OF BLADDER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TT74ZZ | RESECTION OF LT URETER,PEA |

| 10 | 0TT78ZZ | RESECTION OF LT URETER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0TT64ZZ | RESECTION OF RT URETER,PEA |

| 10 | 0TT68ZZ | RESECTION OF RT URETER,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0DT80ZZ | RESECTION OF SMALL INTESTINE,OA |

| 10 | 0DT84ZZ | RESECTION OF SMALL INTESTINE,PEA |

| 10 | 0TTD0ZZ | RESECTION OF URETHRA,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0TTD4ZZ | RESECTION OF URETHRA,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TTD7ZZ | RESECTION OF URETHRA,VN OR AO |

| 10 | 0TTD8ZZ | RESECTION OF URETHRA,VN OR AOE |

| 10 | 0UT90ZZ | RESECTION OF UTERUS,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0UT94ZZ | RESECTION OF UTERUS,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0UT97ZZ | RESECTION OF UTERUS,VN/AO |

| 10 | 0UTG0ZZ | RESECTION OF VAGINA,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0UTG4ZZ | RESECTION OF VAGINA,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0UTG7ZZ | RESECTION OF VAGINA,VN/AO |

| 10 | 0UTG8ZZ | RESECTION OF VAGINA,VN/AOE |

| 10 | 0VT04ZZ | RESECTION PROSTATE, PERCU ENDO APPR |

| 10 | 0VT07ZZ | RESECTION PROSTATE, VN/AO |

| 10 | 0UT00ZZ | RESECTION RT OVARY,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 0UT04ZZ | RESECTION RT OVARY,PERC ENDO APP |

| 10 | 0TT60ZZ | RESECTION RT URETER,OPEN APPROACH |

| 10 | 8E0W3CZ | ROBOTIC ASSISTED PX TRUNK REGION,PA |

Appendix C

| High Volume Hospitals | Non-High-Volume Hospitals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Low 95% CI | High 95% CI | p-Value | OR | Low 95% CI | High 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age, years | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Continue | 1.056 | 1.051 | 1.061 | <0.0001 | 1.068 | 1.066 | 1.071 | <0.0001 |

| Marital Status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married, n (%) | ref | ref | ||||||

| Single/Widowed, n (%) | 2.419 | 2.242 | 2.61 | <0.0001 | 2.216 | 2.136 | 2.229 | <0.0001 |

| Others, n (%) | 0.843 | 0.734 | 0.968 | <0.0001 | 1.738 | 1.63 | 1.852 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | ref | ref | ||||||

| Female | 1.564 | 1.439 | 1.7 | <0.0001 | 1.407 | 1.351 | 1.466 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidity index | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| CCI = 0 | ref | ref | ||||||

| CCI = 1 | 1.673 | 1.378 | 2.032 | 0.3538 | 1.227 | 1.091 | 1.308 | 0.0001 |

| CCI = 2 or greater | 2.411 | 2.083 | 2.791 | <0.0001 | 2.217 | 2.042 | 2.407 | <0.0001 |

| Race, and Etnicity n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||||

| N-H-White | ref | ref | ||||||

| N-H-Black | 1.177 | 1.016 | 1.364 | 0.9397 | 1.006 | 0.929 | 1.089 | 0.8775 |

| Hispanic | 2.191 | 1.777 | 2.702 | 0.9208 | 0.885 | 0.795 | 0.985 | 0.0117 |

| Other | 1.481 | 1.309 | 1.676 | 0.9327 | 0.852 | 0.805 | 0.901 | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | <0.001 | <0.001 | >999.999 | 0.9345 | 1.408 | 1.04 | 1.905 | 0.008 |

| Primary insurance | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Self Pay | 0.288 | 0.134 | 0.621 | <0.0001 | 0.819 | 0.644 | 1.042 | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 2.195 | 1.839 | 2.619 | <0.0001 | 1.906 | 1.721 | 2.11 | <0.0001 |

| Medicare | 1.88 | 1.674 | 2.111 | <0.0001 | 1.858 | 1.751 | 1.97 | <0.0001 |

| HMO/PPO | ref | ref | ||||||

| Others | 2.665 | 2.066 | 3.439 | <0.0001 | 1.672 | 1.495 | 1.87 | <0.0001 |

| Urinary diversion | 0.4696 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Incontinent | ref | ref | ||||||

| Continent | 0.945 | 0.809 | 1.102 | 0.4696 | 0.741 | 0.67 | 0.82 | <0.0001 |

| Hospital size | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| ≤200 | ref | ref | ||||||

| 200–299 | 1.121 | 0.739 | 1.7 | 0.4429 | 0.728 | 0.683 | 0.776 | <0.0001 |

| 300–399 | 1.183 | 0.89 | 1.573 | 0.5197 | 0.803 | 0.755 | 0.854 | 0.1225 |

| ≥400 | 1.777 | 1.374 | 2.297 | <0.0001 | 0.793 | 0.749 | 0.838 | 0.0068 |

| Hospital teaching status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Teaching | ref | ref | ||||||

| Non-teaching | 1.523 | 1.292 | 1.794 | <0.0001 | 1.209 | 1.161 | 1.258 | <0.0001 |

| Hospital Location | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | ||||||

| Urban | ref | ref | ||||||

| Rural | 0.252 | 0.189 | 0.337 | <0.0001 | 0.901 | 0.849 | 0.957 | 0.0007 |

| Region n (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Midwest | ref | <0.0001 | ref | |||||

| Northeast | 1.12 | 1.008 | 1.244 | <0.0001 | 1.343 | 1.269 | 1.422 | <0.0001 |

| South | 0.608 | 0.54 | 0.685 | 0.0008 | 0.721 | 0.69 | 0.753 | <0.0001 |

| West | 0.361 | 0.298 | 0.438 | <0.0001 | 0.746 | 0.709 | 0.785 | <0.0001 |

| Surgical approach | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| open | ref | ref | ||||||

| robotic | 0.634 | 0.58 | 0.693 | <0.0001 | 0.73 | 0.693 | 0.768 | <0.0001 |

| Year of Surgery | ||||||||

| Continue | 1.071 | 1.061 | 1.081 | <0.0001 | 1.051 | 1.047 | 1.055 | <0.0001 |

References

- Alfred Witjes, J.; Lebret, T.; Comperat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; De Santis, M.; Bruins, H.M.; Hernandez, V.; Espinos, E.L.; Dunn, J.; Rouanne, M.; et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaig, T.W.; Spiess, P.E.; Agarwal, N.; Bangs, R.; Boorjian, S.A.; Buyyounouski, M.K.; Chang, S.; Downs, T.M.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Friedlander, T.; et al. Bladder Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stimson, C.J.; Chang, S.S.; Barocas, D.A.; Humphrey, J.E.; Patel, S.G.; Clark, P.E.; Smith, J.A., Jr.; Cookson, M.S. Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. J. Urol. 2010, 184, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, J.G.; Gore, J.L.; Holt, S.K.; Wright, J.L.; Mossanen, M.; Dash, A. Patient-centered risk stratification of disposition outcomes following radical cystectomy. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 235.e7–235.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, S.J.; Pfail, J.L.; Katims, A.B.; Mehrazin, R.; Wiklund, P.; Sfakianos, J.; Waingankar, N. The impact of discharge location on outcomes following radical cystectomy. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 40, 63.e1–63.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Insurance Coverage Status and Type of Coverage by State-All Persons: 2008 to 2019; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Grabowski, D.C.; Afendulis, C.C.; McGuire, T.G. Medicare prospective payment and the volume and intensity of skilled nursing facility services. J. Health Econ. 2011, 30, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, M.A.; Barocas, D.A.; Salem, S.; Clark, P.E.; Cookson, M.S.; Davis, R.; Gregg, J.; Stimson, C.J.; Smith, J.A., Jr.; Chang, S.S. Determining factors for hospital discharge status after radical cystectomy in a large contemporary cohort. J. Urol. 2011, 185, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriault, B.C.; Pazniokas, J.; Adkoli, A.S.; Cho, E.K.; Rao, N.; Schmidt, M.; Cole, C.; Gandhi, C.; Couldwell, W.T.; Al-Mufti, F.; et al. Frailty predicts worse outcomes after intracranial meningioma surgery irrespective of existing prognostic factors. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 49, E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijt, H.J.; Morin, M.L.; Allen, E.; Weaver, M.J. Does the frailty index predict discharge disposition and length of stay at the hospital and rehabilitation facilities? Injury 2021, 52, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciamani, G.E.; Lee, R.S.; Yip, W.; Cai, J.; Miranda, G.; Daneshmand, S.; Aron, M.; Hooman, D.; Gill, I.; Desai, M. Impact of Patient, Surgical, and Perioperative Factors on Discharge Disposition After Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer. J. Urol. 2021, 206, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premier Healthcare Database. WHITE PAPER: PREMIER HOSPITAL DATABASE (PHD)—2 March 2020. 2020. Available online: https://learn.premierinc.com/white-papers/premier-healthcare-database-whitepaper (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Chung, G.; Hinoul, P.; Coplan, P.; Yoo, A. Trends in the diffusion of robotic surgery in prostate, uterus, and colorectal procedures: A retrospective population-based study. J. Robot. Surg. 2021, 15, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.D.; Ananth, C.V.; Lewin, S.N.; Burke, W.M.; Lu, Y.S.; Neugut, A.I.; Herzog, T.J.; Hershman, D.L. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA 2013, 309, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leow, J.J.; Chang, S.L.; Trinh, Q.D. Accurately determining patients who underwent robot-assisted surgery: Limitations of administrative databases. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; ElRayes, W.; Wilson, F.; Su, D.; Oleynikov, D.; Morien, M.; Chen, L.W. Disparities in the receipt of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Between-hospital and within-hospital analysis using 2009–2011 California inpatient data. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossanen, M.; Krasnow, R.E.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Preston, M.A.; Kibel, A.S.; Ha, A.; Gore, J.L.; Smith, A.B.; Leow, J.J.; Trinh, Q.D.; et al. Associations of specific postoperative complications with costs after radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2018, 121, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, J.J.; Cole, A.P.; Seisen, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Mossanen, M.; Menon, M.; Preston, M.A.; Choueiri, T.K.; Kibel, A.S.; Chung, B.I.; et al. Variations in the Costs of Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer in the USA. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assel, M.; Sjoberg, D.; Elders, A.; Wang, X.; Huo, D.; Botchway, A.; Delfino, K.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Koyama, T.; et al. Guidelines for Reporting of Statistics for Clinical Research in Urology. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing Facilities. Medicaid. Available online: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/institutional-long-term-care/nursing-facilities/index.html (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- SNF Care Coverage. Available online: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/skilled-nursing-facility-snf-care (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy—Chapter 8: Skilled Nursing Facility Service; MedPAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, M.A.; Okrainec, A.; Glicksman, A.; Pearsall, E.; Victor, J.C.; McLeod, R.S. Adoption of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) strategies for colorectal surgery at academic teaching hospitals and impact on total length of hospital stay. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerantola, Y.; Valerio, M.; Persson, B.; Jichlinski, P.; Ljungqvist, O.; Hubner, M.; Kassouf, W.; Muller, S.; Baldini, G.; Carli, F.; et al. Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS((R))) society recommendations. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerbocus, M.; Wang, Z.J. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and Radical Cystectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Res. Rep. Urol. 2021, 13, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Domes, T.; Jana, K. Evaluation of an enhanced recovery protocol on patients having radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, N.; Imbimbo, C.; Fusco, F.; Ficarra, V.; Mangiapia, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Creta, M.; Imperatore, V.; Mirone, V. Complications and quality of life in elderly patients with several comorbidities undergoing cutaneous ureterostomy with single stoma or ileal conduit after radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creta, M.; Fusco, F.; La Rocca, R.; Capece, M.; Celentano, G.; Imbimbo, C.; Imperatore, V.; Russo, L.; Mangiapia, F.; Mirone, V.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Evaluation of Renal Function after Radical Cystectomy and Cutaneous Ureterostomy in High-Risk Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathianathen, N.J.; Kalapara, A.; Frydenberg, M.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Weight, C.J.; Parekh, D.; Konety, B.R. Robotic Assisted Radical Cystectomy vs Open Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michels, C.T.J.; Wijburg, C.J.; Hannink, G.; Witjes, J.A.; Rovers, M.M.; Grutters, J.P.C.; Group, R.S. Robot-assisted Versus Open Radical Cystectomy in Bladder Cancer: An Economic Evaluation Alongside a Multicentre Comparative Effectiveness Study. Eur. Urol. Focus 2021, 8, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.P.; Khushalani, J.; Baernholdt, M. Urban-Rural Differences in Skilled Nursing Facility Rehospitalization Rates. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popejoy, L.L.; Wakefield, B.J.; Vogelsmeier, A.A.; Galambos, C.M.; Lewis, A.M.; Huneke, D.; Petroski, G.; Mehr, D.R. Reengineering Skilled Nursing Facility Discharge: Analysis of Reengineered Discharge Implementation. J. Nurs. Care. Qual. 2020, 35, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Home Discharge | CFRs | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of Patients | 113,229 | (82.0%) | 24,922 | (18.0%) | |

| Age, years, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| younger than 55 | 12,711 | (93.5%) | 884 | (6.5%) | |

| 55–64 | 27,594 | (91.6%) | 2545 | (8.4%) | |

| 65–69 | 21,150 | (87.0%) | 3161 | (13.0%) | |

| 70–74 | 21,854 | (81.0%) | 5111 | (19.0%) | |

| 75 or Older | 29,920 | (69.4%) | 13,221 | (30.6%) | |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Male | 94,250 | (83.7%) | 18,406 | (16.3%) | |

| Female | 18,976 | (74.4%) | 6516 | (25.6%) | |

| Comorbidity index, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| CCI = 0 | 9371 | (89.5%) | 1105 | (10.5%) | |

| CCI = 1 | 5160 | (84.6%) | 937 | (15.4%) | |

| CCI 2 or greater | 98,698 | (81.2%) | 22,880 | (18.8%) | |

| Race and Etnicity, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| N-H-White | 88,224 | (81.6%) | 19,836 | (18.4%) | |

| N-H-Black | 5780 | (81.2%) | 1339 | (18.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 3089 | (82.6%) | 651 | (17.4%) | |

| Other | 15,902 | (84.0%) | 3028 | (16.0%) | |

| Unknown | 234 | (77.5%) | 68 | (22.5%) | |

| Primary insurance, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Self-Pay | 1958 | (95.9%) | 83 | (4.1%) | |

| Medicaid | 5658 | (86.3%) | 902 | (13.8%) | |

| Medicare | 68,890 | (76.7%) | 20,907 | (23.3%) | |

| HMO/PPO | 32,706 | (93.1%) | 2424 | (6.9%) | |

| Others | 4017 | (86.9%) | 606 | (13.1%) | |

| Marital Status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Married, n (%) | 69,539 | (86.4%) | 10,962 | (13.6%) | |

| Single/Widowed, n (%) | 32,701 | (73.9%) | 11,520 | (26.1%) | |

| Others | 10,989 | (81.8%) | 2440 | (18.2%) | |

| Surgical Approach | <0.0001 | ||||

| Robotic, n (%) | 22,355 | (83.3%) | 4477 | (16.7%) | |

| Open, n (%) | 90,874 | (81.6%) | 20,445 | (18.4%) | |

| Type of Urinary Diversion | <0.0001 | ||||

| Incontinent n (%) | 101,007 | (81.4%) | 23,113 | (18.6%) | |

| Continent n (%) | 6905 | (90.9%) | 695 | (9.1%) | |

| LOS, days, mean (SD)/ median (IQR) | 9.7 (6.3) | 8.0 (6.0–11.0) | 17.2 (13.9) | 13.0 (8.0–21.0) | <0.0001 |

| LOS ≤ 5days n, (%) | 14,501 | (95.2%) | 733 | (4.8%) | <0.0001 |

| LOS > 5days n, (%) | 98,728 | (80.3%) | 24,189 | (19.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Home Discharge | CFRs | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital volume facility, beds, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≤200 | 10,344 | (78.6%) | 2824 | (21.4%) | |

| 200–299 | 14,711 | (82.4%) | 3132 | (17.6%) | |

| 300–399 | 19,171 | (82.2%) | 4152 | (17.8%) | |

| ≥400 | 69,003 | (82.3%) | 14,814 | (17.7%) | |

| Hospital teaching status n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Teaching | 63,303 | (82.3%) | 13,572 | (17.7%) | |

| Non-teaching | 49,926 | (81.5%) | 11,350 | (18.5%) | |

| Hospital Location n (%) | 0.1078 | ||||

| Urban | 104,272 | (81.9%) | 23,026 | (18.1%) | |

| Rural | 8957 | (82.5%) | 1896 | (17.5%) | |

| Not reported | |||||

| Annual Hospital Volume n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| High | 23,230 | (82.4%) | 4951 | (17.6%) | |

| Intermediate | 67,882 | (82.7%) | 14,204 | (17.3%) | |

| Low | 22,117 | (79.3%) | 5767 | (20.7%) | |

| Annual Surgeon Volume n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| High | 22,354 | (83.9%) | 4285 | (16.1%) | |

| Intermediate | 69,758 | (83.0%) | 14,244 | (17.0%) | |

| Low | 21,117 | (76.8%) | 6393 | (23.2%) | |

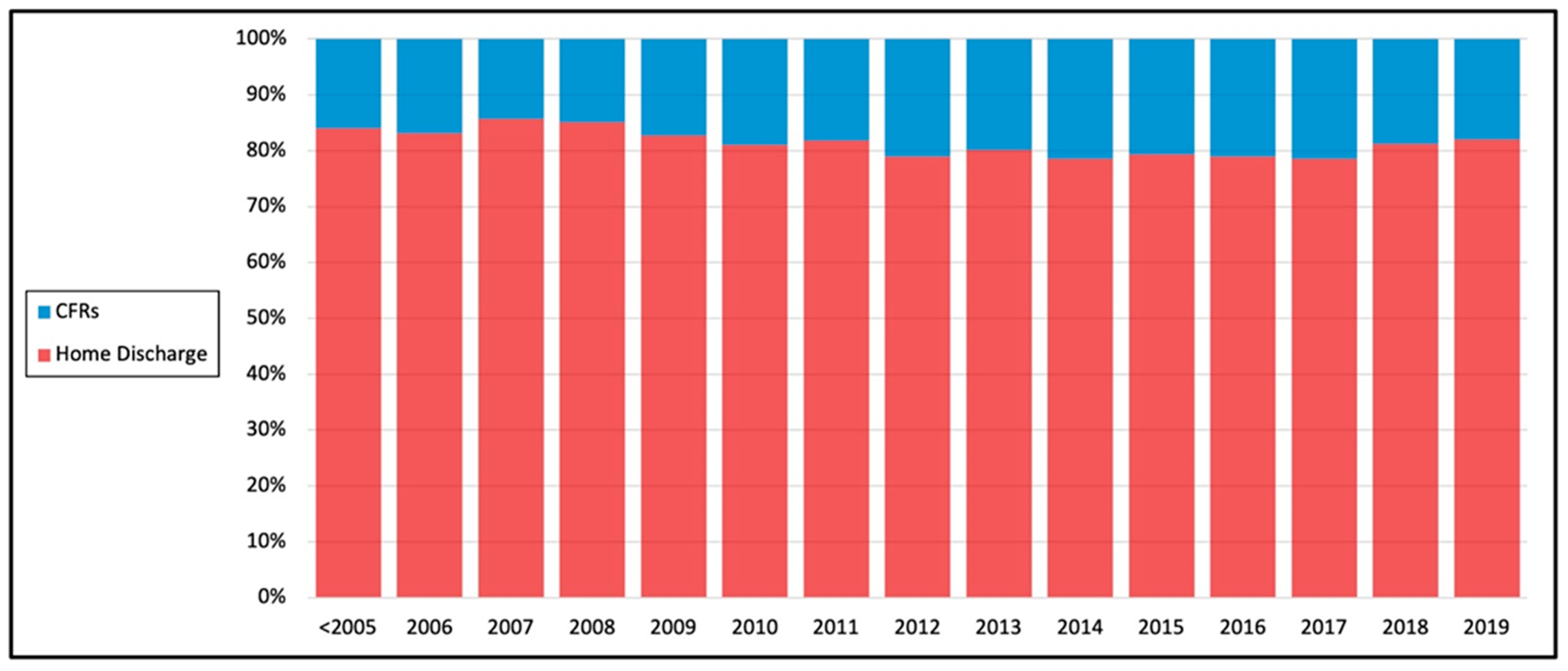

| Year of Surgery n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| <2005 | 32,569 | (84.0%) | 6187 | (16.0%) | |

| 2006 | 5692 | (83.1%) | 1161 | (16.9%) | |

| 2007 | 5920 | (85.7%) | 991 | (14.3%) | |

| 2008 | 6044 | (85.0%) | 1063 | (15.0%) | |

| 2009 | 6023 | (82.7%) | 1261 | (17.3%) | |

| 2010 | 5745 | (81.1%) | 1342 | (18.9%) | |

| 2011 | 5481 | (81.9%) | 1215 | (18.1%) | |

| 2012 | 5118 | (78.9%) | 1368 | (21.1%) | |

| 2013 | 5139 | (80.1%) | 1275 | (19.9%) | |

| 2014 | 5482 | (78.5%) | 1500 | (21.5%) | |

| 2015 | 5991 | (79.3%) | 1562 | (20.7%) | |

| 2016 | 6657 | (79.0%) | 1772 | (21.0%) | |

| 2017 | 6324 | (78.5%) | 1731 | (21.5%) | |

| 2018 | 6226 | (81.2%) | 1437 | (18.8%) | |

| 2019 | 4818 | (82.0%) | 1057 | (18.0%) | |

| Region n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Midwest | 25,572 | (79.0%) | 6801 | (21.0%) | |

| Northeast | 21,484 | (78.6%) | 5833 | (21.4%) | |

| South | 42,969 | (84.5%) | 7862 | (15.5%) | |

| West | 23,204 | (84.0%) | 4426 | (16.0%) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, R.A.; Asanad, K.; Miranda, G.; Cai, J.; Djaladat, H.; Ghodoussipour, S.; Desai, M.M.; Gill, I.S.; Cacciamani, G.E. Population-Based Assessment of Determining Predictors for Discharge Disposition in Patients with Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy. Cancers 2022, 14, 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194613

Kumar RA, Asanad K, Miranda G, Cai J, Djaladat H, Ghodoussipour S, Desai MM, Gill IS, Cacciamani GE. Population-Based Assessment of Determining Predictors for Discharge Disposition in Patients with Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy. Cancers. 2022; 14(19):4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194613

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Raj A., Kian Asanad, Gus Miranda, Jie Cai, Hooman Djaladat, Saum Ghodoussipour, Mihir M. Desai, Inderbir S. Gill, and Giovanni E. Cacciamani. 2022. "Population-Based Assessment of Determining Predictors for Discharge Disposition in Patients with Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy" Cancers 14, no. 19: 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194613

APA StyleKumar, R. A., Asanad, K., Miranda, G., Cai, J., Djaladat, H., Ghodoussipour, S., Desai, M. M., Gill, I. S., & Cacciamani, G. E. (2022). Population-Based Assessment of Determining Predictors for Discharge Disposition in Patients with Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy. Cancers, 14(19), 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194613