Communication Tools Used in Cancer Communication with Children: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.5. Data Charting and Data Item

2.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

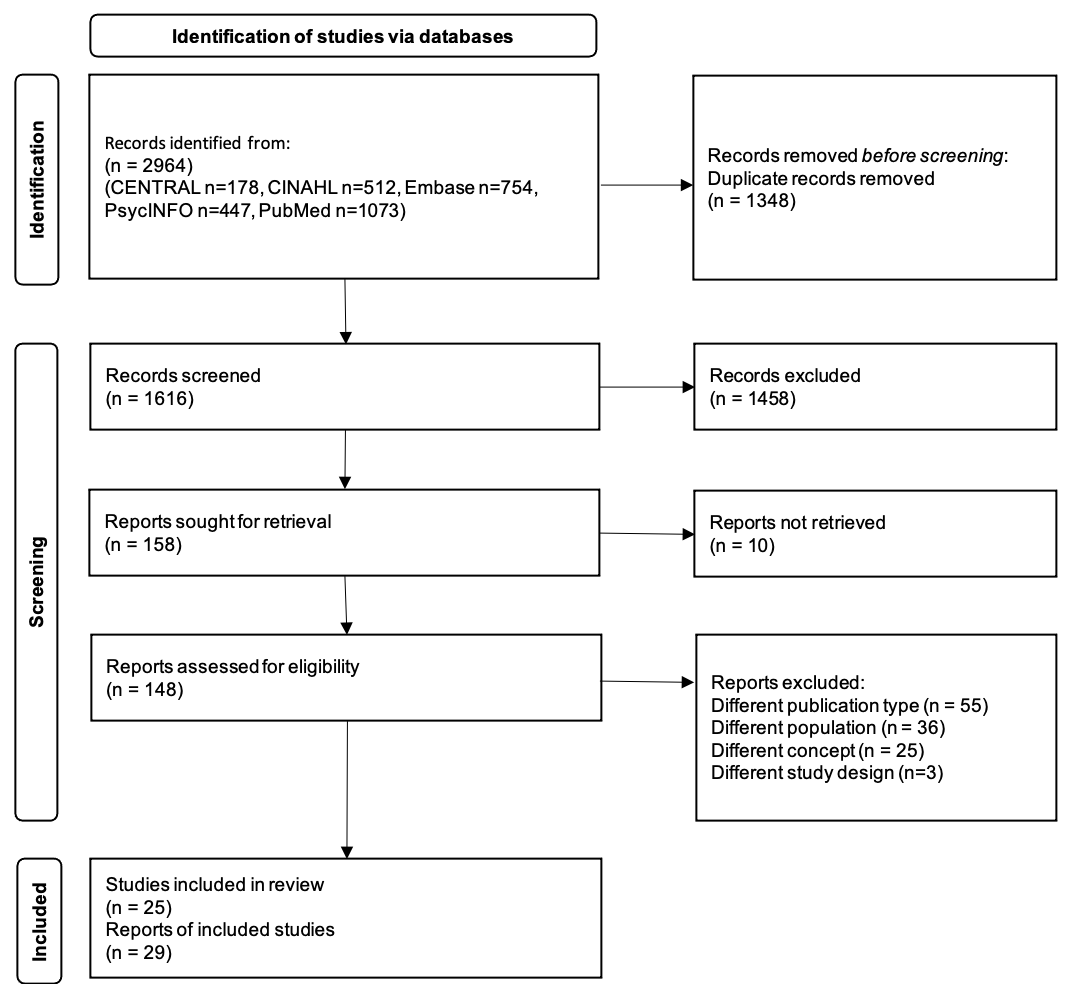

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics and Results of Sources of Evidence

| Author, Year | Study Design | Purpose of the Study | Study Setting | Study Participants | Intervention or Concept | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artilheiro, 2011 [42] | Exploratory descriptive study | To describe the use of therapeutic play (TP) in the preparation, and to identify manifestation during TP session | At the oncology outpatient department from Hospital Infantil Darcy Vargas, São Paulo in Brazil | Children (3–6 years old) who submitted to chemotherapy in the outpatient department (N = 30) | Therapeutic play during the chemotherapy |

|

| Arvidsson, 2016 [43] Baggott, 2015 [58] | User-experience design | To redesign Sisom and validate and adapt it for use in a Swedish population of children with cancer | Sweden | Swedish translators (n = 4), Norwegian translators (n = 2), pediatric nurses working with the care of children with cancer (n = 2), and healthy children (n = 2) | Interactive computer-based assessment and communication tool for children with cancer |

|

| Beltran, 2013 [57] | Qualitative study | To assess the effect of the video games | Children’s Cancer Hospital, Texas in United States of America (USA) | Children with cancer and survivors (9–12 years old) who have a high risk of obesity (N = 28) | Escape from Diab and Nanos warm: Invasion from Inner Space are videogames about preventing obesity |

|

| Bisignano, 2006 [33] | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | To assess the influence of a developmentally specific compact disc read-only memory (CD-ROM) intervention | Oncology clinic at a large urban medical center in USA | Children (7–18 years old) scheduled for IV procedures (N = 30) | CD-ROM designed to help children learn about the medical procedure |

|

| Dragone, 2002 [34] | RCT | To assess the effect of CD-ROM compared with the book | District of Columbia, Virginia, and Ohio in USA | Children with leukemia (4–11 years old) (N = 14 + 7), and their families (N = 16 + 8) | CD-ROM designed to improve children’s feelings control and understanding of leukemia |

|

| Fazalniya, 2017 [35] | RCT | To investigate the effect of an interactive computer game | One hospital in Iran | Children with cancer (8–12 years old), were receiving treatment and undergoing at least 4 months of chemotherapy (N = 64) | The intervention program included an educational-entertainment computer game named “The City of Dreams” which was developed by authors. |

|

| Frygner-Holm, 2020 [44] | Mixed method | To develop and evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a pretend play intervention | Three universities in Sweden, USA, and Germany | Children with cancer (4–10 years old) (N = 5) | Pretend play to support children’s communication, self-efficacy, and coping ability in the care setting |

|

| Fuemmeler, 2020 [45] | Feasibility study-quasi-experimental single-group pretest/posttest design | To describe the development and initial feasibility evaluation of the intervention | Two pediatric oncology clinics, Duke University and Chapel Hill in USA | Pair of pediatric cancer survivors (12–17 years old) and their parents (N = 16) | App-based game “Mila Blooms” that promotes healthy eating and physical activity among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer |

|

| Greenspoon, 2019 [46] | Feasibility study | To assess (1) the understandability, actionability, and readability of the video; (2) patient and caregiver perceptions, knowledge, and interest in FP; and (3) satisfaction with a patient education video | At oncology clinics at a pediatric center and an adult center (not specified country setting) | Patients (13–39 years old) after minimum 1 month from diagnosis (N = 108) (pediatric center: n = 30; average age, 17 years; adult center: n = 78; average age, 30 years) and 39 caregivers or partners (pediatric center, n = 30; adult center, n = 9) | Whiteboard video to explain egg cryopreservation to patients and families |

|

| Jones, 2010 [36] | RCT | To develop and assess the effects of developed CD-ROM compared with Handbook | Four pediatric oncology programs, Los Angeles (California), District of Columbia, Hershey (Pennsylvania), and New York City in USA | Children with solid tumors (12–18 years old), had being treated or within 3 years of treatment (N = 185) However, the final sample consisted of 65 children (CD-ROM: n = 35, Handbook: n = 30) | CD-ROM to educate adolescents about their cancer |

|

| Kato, 2008 [37] Beale, 2006 [60] Beale, 2007 [59] Kato, 2006 [61] | RCT | To determine the effectiveness of a video-game intervention | 34 cancer treatment centers in USA, Canada, and Australia | Youth with cancer (13–29 years old), were receiving treatment and were expected to remain on treatment for at least 4–6 months. (N = 375) Age 13–18 (N = 324, 87.3%) and age 19–29 (N = 47, 12.7%) | Re-Mission was designed to be a learning environment that motivates, guides, and supports the learning of a set of behavioral objectives related to self-care during treatment for cancer. (http://www.re-mission.com/) (accessed on 20 September 2022) |

|

| Kock, 2015 [47] | Feasibility study-cross-sectional study | To increase compliance with follow-up examinations using a reminding service | Two locations: the University Medical Center in Lübeck and the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany | Former patients from the age of 15 and their relatives (N = 22) | Mobile application to provide the information on late effects of childhood cancer |

|

| Kurt, 2013 [38] | Before-after controlled study | To determine the effects of Re-Mission video game | At two hospitals, Istanbul in Turkey | Adolescents with cancer (13–18 years old) (N = 61) | Re-Mission was designed to be a learning environment that motivates, guides, and supports the learning of a set of behavioral objectives related to self-care during treatment for cancer (http://www.re-mission.com/) (accessed on 20 September 2022) |

|

| Li, 2011 [39] | A non-equivalent control group pretest–post-test, between-subject design | To examine the effectiveness of therapeutic play, using virtual reality computer games | One of the largest acute-care hospitals, Hong Kong in China | Hong Kong Chinese children hospitalized with cancer (8–16 years old) (N = 120) | 30-minutes therapeutic play intervention by research nurse using virtual reality computer games daily (five days a week) |

|

| Linder, 2021 [48] | Feasibility study–qualitative study by interviews | To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a newly developed game-based symptom-reporting app | A children’s hospital in the USA | Children with cancer, (6–12 years old) were undergoing treatment (N = 19) | Game-based symptom-reporting app, “Color Me Healthy” |

|

| Murphy, 2012 [49] | Qualitative study by face-to-face interviews | To test the design, readability, likelihood to read, and overall opinion of a pediatric fertility preservation brochure | Children’s Cancer Center and All Children’s Hospital, Florida in USA | Children with cancer and survivors (12–21 years old) (N = 7), their parents (N = 11), and healthcare professionals (N = 6) | Two versions of gender concordant brochures on fertility for pediatric oncology patients and their parents |

|

| O’Conner-Von, 2009 [50] | Qualitative study by interviews | To develop and validate an innovative, interactive web-based educational program | Pediatric oncology clinic at a university medical center in USA | Adolescents who had completed cancer treatment within the past 12 months (10–16 years old) (N = 4) and their parents (N = 5) | Web-based educational program to cope with cancer |

|

| Pitillas, 2018 [51] | Qualitative study | To delineate a systematic approach for the use of play therapy (PT) among psychotherapists working within the field of pediatric oncology | Not reported | Children with cancer (3 years old) (N = 1) | Psychoanalytic PT depending on children’s needs and developmental stages |

|

| Ruland, 2007 [52] | Qualitative study | To describe the process of development of the computer application, “SISOM” | The principal of a nearby elementary school in Oslo, Norway Design sessions were held at the “Adolescent Club Room” within the pediatric department in Norway’s National Hospital, Rikshospitalet, Oslo in Norway | Children in 4th (9 years old) and 6th (11 years old) grade (N = 50). The final group consisted of 12 children who worked in two separate design groups: one group of six 4th graders (9 years old) and one group of 6th graders (11 years old). Other children participated in other tasks | SISOM, a handheld, portable computer application to (1) help children with cancer aged 7–12 years old, communicate their symptoms/problems in a child-friendly, age-adjusted manner; and (2) assist clinicians in better addressing children’s experienced symptoms and problems in patient care |

|

| Sajjad, 2014 [40] | Experimental study | To measure the psychological symptoms in children with brain cancer and work on them through game therapy compared with control group | Three hospitals in Pakistan | Children with brain cancer (10–14 years old) (N = 76) | 3D Graphical Imagery Therapy game on psychological signs of cancer patients fighting against brain cancer |

|

| Sposito, 2016 [53] | Exploratory study with qualitative data analysis | To present the experience of using finger puppets as a playful strategy | At the pediatric oncology ward of a public teaching hospital in Brazil | Hospitalized children with cancer (7–12 years old), were undergoing chemotherapy treatment (N = 10) | Using puppets as a playful strategy during the interviews with hospitalized children with cancer |

|

| Tsimicalis, 2017 [54] | Single-site, descriptive, qualitative study | To produce a Sisom, interactive tool French version that is (1) clear, comprehensible, and understandable; (2) culturally and clinically meaningful; and (3) conceptually equivalent to the original version | At pediatric hospital, Montreal in Canada | Healthcare professionals who provided care in French to children with cancer (N = 5) Children with cancer (6–12 years old) (N = 10) and their parents (N = 10) | Interactive assessment and communication tool designed to provide children with a voice |

|

| Tsimicalis, 2018 [55] | Multisite descriptive study | To test the usability of Sisom | Three university-affiliated health centers in Canada | Children with cancer (6–12 years old), were received treatment or follow-up care at one of the study sites and their parents (N = 34) | Interactive assessment and communication tool designed to provide children with a voice |

|

| Tyc, 2003 [41] | RCT | To determine whether a risk counseling intervention would increase knowledge and perceived vulnerability to tobacco-related health risks and decrease future intentions to use tobacco | St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis in USA | Preadolescents and adolescents (10–18 years old), were previously treated for cancer (N = 103) | Educational video and risk counseling intervention was designed to be administered in a single session with periodic reinforcement of tobacco goals by telephone |

|

| Wiener, 2011 [56] | Pilot study, cross-sectional study | To learn how the game is being used in clinical settings and to gather information regarding the usefulness of ShopTalk | 2009 American Pediatric Oncology Social Work (APOSW) annual meeting | Healthcare professionals (N = 110) | Therapeutic game to help youth living with cancer talk about their illness in a non-threatening way |

|

3.3. Synthesis of Results

| Author, Year | Contents | Mode/Type | Target Population | Developer | Access (e.g., Cost, Website, Article) | Usage Instructions | Evaluation or Validation of Communication Tool | Impact of Communication Tools on Health Outcomes and Outcome Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For children | ||||||||

| Artilheiro, 2011 [42] | Therapeutic Play (TP) using a doll and other materials during chemotherapy such as: an intravenous device, cotton, syringe, needle, tourniquet, infusion pump, adhesive tape, and gauze, among others | Nurse-led TP during the chemotherapy | Not specified. However, it must be children with cancer | Not specified | Not reported | TP using doll and other materials. Investigator was telling a story about a child who had undergone chemotherapy, and children repeated the story by themselves | Exploratory descriptive study Observation and interview |

|

| Arvidsson, 2016 [43] Baggott, 2006 [58] Ruland, 2007 [52] Tsimicalis, 2017 [54] Tsimicalis, 2018 [55] | Together with a self-selected avatar, the child sets out on a virtual journey from island to island (5 islands in total: “At the hospital,” “About managing things,” “My body,” “Thoughts and feelings,” and “Things one can be afraid of”) | Interactive computer-based communication tool with spoken texts, sounds, animations, and intuitively meaningful metaphors and pictures to represent symptoms and problems | Children with cancer (6–12 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Stage 1: translated original version of Sisom (Norwegian) into Swedish Stage 2: understanding evaluation by healthy children and pediatric nurses Stage 3: interactive low- and high-fidelity evaluations |

|

| Beltran, 2013 [57] |

| Video games used state-of-the-art software and three-dimensional computer graphics | Preadolescents with cancer and survivors (9–12 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | Computer games are played on computers loaned to the participants at their home. However, there was no detailed description on how to use the tool | Use-experience qualitative study |

|

| Bisignano, 2006 [33] | Compact disc read-only memory (CD-ROM) was designed to help children learn about the medical procedure, includes four components: education/information, preprocedural preparation (video modeling), breathing exercises, and distracting imagery | CD-ROM, “Spotlight on IVs” | Children with hematological or oncological diagnosis (7–18 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | Participants had approximately 20 min to instruct on how to use the computer and CD-ROM. | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) |

|

| Fazalniya, 2017 [35] | Hero and difficult struggle, championship is not related to hair, everything is calm, tales of lethargy and fatigue, tales of nausea and loss of appetite, inside of the body which contained healthy and unhealthy cells, and side effects of chemotherapy | Educational entertainment computer game, “The City of Dreams” | Not specified must be children with cancer | Not specified | Not reported | A training session was held for the children and parents regarding the content of the computer game, how to load it, and the entire process of installing and using the software. Then, to ensure that the children and parents had learned the mentioned steps, they were asked to perform the steps for the researcher | RCT |

|

| Frygner-Holm, 2020 [44] | First story stem was based on imagination, the second was based on affect, and the third was medical play made up from variety of situations commonly experienced by children undergoing treatment for cancer | Pretend play using a variety of medical play toys and nonmedical play toys | Children with cancer (4–10 years old) | A project of international collaboration | Not reported This intervention needs the play facilitator | The play facilitator and child were alone in the room and they instructed children Pretend play consisted of six to eight 25–35 min sessions. | Mixed method |

|

| Fuemmeler, 2020 [45] | Application (app) includes (1) an app and backend administrative dashboard; (2) brief phone meetings with a health coach; and (3) educational print materials for each child and parent | Smartphone applications, “The Mila Blooms” | Childhood survivors, aged 12–17 years old | Not specified | Not reported | There was a description about usage for the study participants. However, there was no description for general | Quasi-experimental single-group pretest/posttest |

|

| Jones, 2010 [36] | Although there was a description about recommendation from adolescents, parents, and healthcare professionals, there was no detailed description | CD-ROM | Adolescents with solid tumors (12–18 years old) | Consulting company and healthcare professionals | Not reported | The user can navigate easily from one area to another throughout the CD-ROM, using TV screens or menus. A glossary is included to explain specific terms (highlighted in the text), and games are included throughout the CD-ROM | RCT |

|

| Kato, 2008 [37] Beale, 2006 [60] Beale, 2007 [59] Kato, 2006 [61] Kurt, 2013 [38] | Destroying cancer cells and managing common treatment-related adverse effects such as bacterial infections, nausea, and constipation by using chemotherapy, antibiotics, antiemetics, and a stool softener as ammunition | Personal computer game, “Re-Mission” | Adolescents and young adults, aged 13–29 years old | HOPELAB: a team of behavioral scientists, designers, impact investors, and digital tech experts | www.re-mission.net (accessed on 20 September 2022) | The players control a nanobot, “Roxxi,” in three-dimensional environments within the bodies of young patients with cancer. However, there was no detail description on how to use the tool | RCT |

|

| Li, 2011 [39] | A variety of group playing activities, in particular, involves using virtual reality through interactive simulations created by computer hardware and software to present children to engage in environments that appear and feel similar to re-al-work objects and events | Therapeutic play (TP) using virtual reality computer games by research nurses in the playroom | Children with cancer (8–16 years old), were undergoing active treatment | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Pre- and post- test with control group |

|

| Linder, 2021 [48] | The app supports the report of the prevalence, severity, and associated bother of eight general symptoms: pain, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, difficulty sleeping, appetite changes, coughing, and dizziness. | Game-based symptom-reporting app, “Color Me Healthy” | Children with cancer (6–12 years old), were undergoing active treatment | Not specified; however, children and clinicians provided input regarding symptoms | Not reported | Children receive up to two daily rewards: one for logging into the app and a second for completing key daily tasks within the app. However, there was no detailed description of how to use the tool | Verification of children’s app usage and interview survey |

|

| O’Conner-Von, 2009 [50] | Core components of the program include information about (a) cancer, (b) cancer treatment, (c) feelings about having cancer, (d) dealing with friends and school, (e) healthy coping strategies, and (f) advice from the adolescent cancer experts | Web-based educational program “Coping with Cancer” | Children with cancer (10–16 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Not assessed, but they planned a field test of the program next |

|

| Pitillas, 2018 [51] | There are components related to these aims. (1) Reality testing and ego strengthening, and (2) unveiling and working through unconscious conflicts related to disease, and (3) defense maturation and problem solving | Psychoanalytic PT | Children with cancer (18 months-14 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

| Sajjad, 2014 [40] | The main theme is that the patient hits the enemy character through the powerful use of weapons (white blood cells). The enemy character (a brain tumor) is targeted and destroyed, increasing the patient’s health bar. | 3D Graphical Imagery Therapy game | Children with a brain tumor, (10–14 years old) | Not specified | Not reported | The clinical psychologist instructed the game to the patients. However, there was no detailed description of how to use the tool | Quasi-experimental controlled pretest/posttest |

|

| Sposito, 2016 [53] | 1. The making of the puppet by the child, followed by the child interview using the puppets. 2. The use of puppets as a playful strategy during the interviews with hospitalized children with cancer was structured | Interviews (54–71 min) using puppets | Children with cancer (7–12 years old) | Researcher The first author, an occupational therapist, conducted the interview. | Not reported | Making of the puppet and following the child’s interview using the puppets | Use-experience qualitative study |

|

| Tyc, 2003 [41] | Educational video that discussed the short- and long-term physical and social consequences of tobacco use; late effects risk counseling focused on potential chemotherapy and radiation treatment-related toxicities that can be exacerbated by tobacco use and the survivors’ increased vulnerability to tobacco-related health risks relative to their healthy peers | Educational video to reduce intentions to use tobacco among pediatric cancer survivors, Qualitative study | Preadolescents and adolescents with cancer (Not specified the ages) | Not specified | Not reported | A master’s level psychologist provided the intervention over 50–60 min, and a trained research nurse conducted the follow-up telephone counseling. However, there was no detailed description of how to use the tool | RCT |

|

| Wiener, 2011 [56] | ShopTalk consists of a colorful board with ten stores, each with a set of 15 question cards related to the theme of the individual store (150 questions total) | Therapeutic game, “Shop Talk” | Children with cancer (7–16 years old) | Researcher | It was distributed for the pilot study. However, there was no description of the access to general | Players roll the dice to move their “shopping bag” piece around the board, attempting to enter each store, at which point they become a “customer” and are asked a question by another player. However, there was no detailed description of how to use the tool | They planned a randomized controlled trial as a next step |

|

| For children and their families | ||||||||

| Dragone, 2002 [34] | The Get Better Place (research studies, medicines, treatment, health care team), Help Yourself (areas in which children can exert some control, including nutrition, preventing infections, pain control, creative arts, and relaxation techniques), The Testing Center (bone marrow tests and spinal taps, blood tests, radiology tests, heart testing, and vital signs), The Filland Fly (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets), The Space Mall (changes in appearance, central venous catheters, anatomy and physiology, and resource/reference section), and The Movies (video hospital tour, living with leukemia, expert explanation of leukemia, and siblings’ views of leukemia) | CD-ROM, “Kidz with Leukemia: A Space Adventure” | Children with leukemia, (4–11 years old) and their families | Healthcare professionals | Not reported | The intervention group received the CD-ROM, Kidz with Leukemia: A Space Adventure, to use for approximately 3 months. However, there was no detailed description on how to use the tool | RCT |

|

| Greenspoon, 2019 [46] | Relevant anatomy, physiology of ovulation, egg retrieval, and process of cryopreservation | 7-minute whiteboard video with hand-drawn sketches in full color | Patients with cancer, (13–39 years old) and parents | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Questionnaires survey |

|

| Kock, 2015 [47] | Disease, a reminder service for follow-up examinations, and a calendar function to coordinate these examinations | Android mobile application | Children with childhood cancer (>15 years old) and their relatives | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Questionnaire survey: usability questionnaires following the ISO 9241/110 norm |

|

| Murphy, 2012 [49] | Cancer-related infertility and the options available for pediatrics based on available literature and existing brochures from Moffitt Cancer Center, Fertile Hope, and the Onco-fertility Consortium | Gender concordant brochures | Pediatric oncology patients and parents (Ages not specified) | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Interview survey |

|

| For healthcare professionals | ||||||||

| No communication tool was identified. | ||||||||

3.3.1. Communication Tools with Children with Cancer

3.3.2. How to Use Communication Tools

3.3.3. How to Validate and Evaluate Communication Tools

3.3.4. The Impacts of Communication Tools on Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Practices and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Colombet, M.; Ries, L.A.G.; Moreno, F.; Dolya, A.; Bray, F.; Hesseling, P.; Shin, H.Y.; Stiller, C.A.; Bouzbid, S.; et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–10: A population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, J.; Powell, R.A.; Marston, J.; Huwa, C.; Chandra, L.; Garchakova, A.; Harding, R. Children’s palliative care in low- and middle-income countries. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.M.; Dunn, M.J.; Zuckerman, T.; Vannatta, K.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Compas, B.E. Cancer-related sources of stress for children with cancer and their parents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2012, 37, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, O.; Moro, M.R.; Baubet, T.; Revah-Lévy, A.; Flament, M.F. Posttraumatic stress symptoms after childhood cancer. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 12, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Amory, A.; Gibson, F.; Kiernan, G. Information-sharing between healthcare professionals, parents and children with cancer: More than a matter of information exchange. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Elger, B.S.; Wangmo, T. Missing life stories. The narratives of palliative patients, parents and physicians in paediatric oncology. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalmsell, L.; Kontio, T.; Stein, M.; Henter, J.I.; Kreicbergs, U. On the Child’s Own Initiative: Parents Communicate with Their Dying Child About Death. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, K.M.; Wangmo, T.; De Clercq, E.; Badarau, D.O.; Ansari, M.; Kühne, T.; Niggli, F.; Elger, B.S. Putting patient participation into practice in pediatrics-results from a qualitative study in pediatric oncology. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Dalton, L.; Rapa, E.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Hanington, L.; Stein, K.F.; Ziebland, S.; Rochat, T.; Harrop, E.; Kelly, B.; et al. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of their own life-threatening condition. Lancet 2019, 393, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, N.; Suto, M.; Takemoto, Y.; Suzuki, D.; Lopes, K.D.S.; Ota, E. Supporting the Decision Making of Children With Cancer: A Meta-synthesis. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs 2020, 37, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Wiener, L.; Mack, J.; Wolfe, J. Prognostic Disclosures to Children: A Historical Perspective. Pediatrics 2016, 138, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masera, G.; Chesler, M.; Jancovic, M.E.A. Guidelines for the Communication of the Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.childhoodcancerinternational.org/guidelines-for-the-communication-of-the-diagnosis/ (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Zwaanswijk, M.; Tates, K.; van Dulmen, S.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; Kamps, W.A.; Bensing, J.M. Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: Results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatr. 2007, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graves, S.; Aranda, S. Living with hope and fear--the uncertainty of childhood cancer after relapse. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaji, N.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Hasegawa, D.; Yuza, Y.; Ota, E. Information needs of children with leukemia and their parents’ perspectives of their information needs: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatrics 2022, 22, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.P.; Mowbray, C.; Pyke-Grimm, K.; Hinds, P.S. Identifying a conceptual shift in child and adolescent-reported treatment decision making: “Having a say, as I need at this time”. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, K.M.; Badarau, D.O.; Brazzola, P.; Hengartner, H.; Elger, B.S.; Wangmo, T. Participation in pediatric oncology: Views of child and adolescent patients. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, L.; Graham, I.D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Jull, J.; Shephard, A.; Lawson, M.L.; Davis, A.; Yameogo, A.; Stacey, D. Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents; NCI: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Blazin, L.J.; Cecchini, C.; Habashy, C.; Kaye, E.C.; Baker, J.N. Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice. Children 2018, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; Brien, K.K.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 350, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamaji, N.; Suzuki, D.; Suto, M.; Sasayama, K.; Ota, E. Communication tools used in cancer communication with children: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Baldini Soares, C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ranmal, R.; Prictor, M.; Scott, J.T. Interventions for improving communication with children and adolescents about their cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2, Cd002969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Featherstone, R.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Paynter, R.; Rader, T.; et al. Chapter 4: Searching for and Selecting Studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane Library: Cochrane, AL, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lasserson, T.; Churchill, R.; Chandler, J.; Tovey, D.; Thomas, J.; Flemyng, E.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Standards for the Reporting of New Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Available online: https://community.cochrane.org/sites/default/files/uploads/MECIR%20PRINTED%20BOOKLET%20FINAL%20v1.01.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; et al. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Bisignano, A.; Bush, J.P. Distress in pediatric hematology-oncology patients undergoing intravenous procedures: Evaluation of a CD-ROM intervention. Child. Health Care 2006, 35, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dragone, M.A.; Bush, P.J.; Jones, J.K.; Bearison, D.J.; Kamani, S. Development and evaluation of an interactive CD-ROM for children with leukemia and their families. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 46, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fazelniya, Z.; Najafi, M.; Moafi, A.; Talakoub, S. The Impact of an Interactive Computer Game on the Quality of Life of Children Undergoing Chemotherapy. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2017, 22, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.K.; Kamani, S.A.; Bush, P.J.; Hennessy, K.A.; Marfatia, A.; Shad, A.T. Development and evaluation of an educational interactive CD-ROM for teens with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 512–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, P.M.; Cole, S.W.; Bradlyn, A.S.; Pollock, B.H. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e305–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, A.S.; Savaser, S. The effect of re-mission video game on the quality of life of adolescents with cancer. Turk. Onkol. Derg. 2013, 28, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Chung, J.O.; Ho, E.K. The effectiveness of therapeutic play, using virtual reality computer games, in promoting the psychological well-being of children hospitalised with cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjad, S.; Abdullah, A.H.; Sharif, M.; Mohsin, S. Psychotherapy through video game to target illness related problematic behaviors of children with brain tumor. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 2014, 10, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyc, V.L.; Rai, S.N.; Lensing, S.; Klosky, J.L.; Stewart, D.B.; Gattuso, J. Intervention to reduce intentions to use tobacco among pediatric cancer survivors group received more intensive late effects risk counseling in addition to an educational video, goal setting, written physician feedback, smoking literature, and follo. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 27, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artilheiro, A.P.S.; Almeida, F.d.A.; Chacon, J.M.F. Use of therapeutic play in preparing preschool children for outpatient chemotherapy. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2011, 24, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Gilljam, B.M.; Nygren, J.; Rul, C.M.; Nordby-Bøe, T.; Svedberg, P. Redesign and Validation of Sisom, an Interactive Assessment and Communication Tool for Children With Cancer. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frygner-Holm, S.; Russ, S.; Quitmann, J.; Ring, L.; Zyga, O.; Hansson, M.; Ljungman, G.; Höglund, A.T. Pretend Play as an Intervention for Children With Cancer: A Feasibility Study. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 37, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuemmeler, B.F.; Holzwarth, E.; Sheng, Y.; Do, E.K.; Miller, C.A.; Blatt, J.; Rosoff, P.M.; Østbye, T. Mila Blooms: A Mobile Phone Application and Behavioral Intervention for Promoting Physical Activity and a Healthy Diet Among Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Games Health J. 2020, 9, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspoon, T.; Charow, R.; Papadakos, J.; Samadi, M.; Maloney, A.M.; Paulo, C.; Forcina, V.; Chen, L.; Thavaratnam, A.; Mitchell, L.; et al. Evaluation of an Educational Whiteboard Video to Introduce Fertility Preservation to Female Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. JCO Oncol. Prac. 2019, 16, e488–e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, A.K.; Kaya, R.; Müller, C.; Andersen, B.; Langer, T.; Ingenerf, J. A mobile application to manage and minimise the risk of late effects caused by childhood cancer. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2015, 210, 798–802. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, L.A.; Newman, A.R.; Stegenga, K.; Chiu, Y.S.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Kramer, H.; Weir, C.; Narus, S.; Altizer, R. Feasibility and acceptability of a game-based symptom-reporting app for children with cancer: Perspectives of children and parents. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.; Sawczyn, K.K.; Quinn, G.P. Using a patient-centered approach to develop a fertility preservation brochure for pediatric oncology patients: A pilot study. J Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2012, 25, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Conner-Von, S. Coping with cancer: A Web-based educational program for early and middle adolescents. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2009, 26, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitillas, C.; Martin, J. Knowing what to do, when, and how: An integrative approach to the use of psychoanalytic play therapy with children affected by cancer. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2018, 17, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruland, C.; Slaughter, L.; Starren, J.; Vatne, T.M.; Moe, E.Y. Children’s contributions to designing a communication tool for children with cancer. Stud. Health Technol Inf. 2007, 129, 977–982. [Google Scholar]

- Sposito, A.M.; de Montigny, F.; Sparapani Vde, C.; Lima, R.A.; Silva-Rodrigues, F.M.; Pfeifer, L.I.; Nascimento, L.C. Puppets as a strategy for communication with Brazilian children with cancer. Nurs. Health Sci. 2016, 18, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimicalis, A.; Le May, S.; Stinson, J.; Rennick, J.; Vachon, M.F.; Louli, J.; Bérubé, S.; Treherne, S.; Yoon, S.; Nordby Bøe, T.; et al. Linguistic Validation of an Interactive Communication Tool to Help French-Speaking Children Express Their Cancer Symptoms. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimicalis, A.; Rennick, J.; Stinson, J.; May, S.L.; Louli, J.; Choquette, A.; Treherne, S.; Berube, S.; Yoon, S.; Rul, E.; et al. Usability Testing of an Interactive Communication Tool to Help Children Express Their Cancer Symptoms. J. Pediatr Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 35, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Battles, H.; Mamalian, C.; Zadeh, S. ShopTalk: A pilot study of the feasibility and utility of a therapeutic board game for youth living with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, A.; Li, R.; Ater, J.; Baranowski, J.; Buday, R.; Thompson, D.; Chra, J.; Baranowski, T. Adapting a Videogame to the Needs of Pediatric Cancer Patients and Survivors. Games Health J. 2013, 2, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggott, C.; Baird, J.; Hinds, P.; Rul, C.M.; Miaskowski, C. Evaluation of Sisom: A computer-based animated tool to elicit symptoms and psychosocial concerns from children with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, I.L.; Kato, P.M.; Marin-Bowling, V.M.; Guthrie, N.; Cole, S.W. Improvement in cancer-related knowledge following use of a psychoeducational video game for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, I.L.; Marin-Bowling, V.M.; Guthrie, N.; Kato, P.M. Young cancer patients’ perceptions of a video game used to promote self care. Int. Electron. J. Health Educ. 2006, 9, 202–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, P.M.; Beale, I.L. Factors affecting acceptability to young cancer patients of a psychoeducational video game about cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 23, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrozsi, S.; Trowbridge, A.; Mack, J.W.; Rosenberg, A.R. Effective Communication for Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Patients With Cancer: Considerations for the Patients, Family Members, Providers, and Multidisciplinary Team. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, S.; Hooper, C.-A.; Dyson, C.; Cabral, C. Ethical challenges in conducting research with hard to reach families. Child Abus. Rev. 2008, 17, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, G.; Hart, J.; O’Mathúna, D.; Mattellone, E.; Potts, A.; O’Kane, C.; Shusterman, J.; Tanner, T. What We Know about Ethical Research Involving Children in Humanitarian Settings: An Overview of Principles, the Literature and Case Studies; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Breyer, T.; Storms, A. Empathy as a Desideratum in Health Care—Normative Claim or Professional Competence? Interdiscip. J. Relig. Transform. Contemp. Soc. 2021, 7, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Harvey, K.; Friedrich, A.B.; Antes, A.L.; Yaeger, L.H.; Mack, J.W.; DuBois, J.M. Multilevel barriers and facilitators of communication in pediatric oncology: A systematic review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R. How to Make Communication Among Oncologists, Children With Cancer, and Their Caregivers Therapeutic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2122536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Gutman, T.; Hanson, C.S.; Ju, A.; Manera, K.; Butow, P.; Cohn, R.J.; Dalla-Pozza, L.; Greenzang, K.A.; Mack, J.; et al. Communication during childhood cancer: Systematic review of patient perspectives. Cancer 2020, 126, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhof, S.L.; Vinkers, C.H.; van Geelen, S.M.; Duijff, S.N.; Achterberg, E.J.M.; van der Net, J.; Veltkamp, R.C.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; van de Putte, E.M.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; et al. Healthy play, better coping: The importance of play for the development of children in health and disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 95, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Communication in Cancer Care (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/adjusting-to-cancer/communication-hp-pdq (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy on Integrated People-Centred Health Services 2016–2026; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamaji, N.; Suzuki, D.; Suto, M.; Sasayama, K.; Ota, E. Communication Tools Used in Cancer Communication with Children: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194624

Yamaji N, Suzuki D, Suto M, Sasayama K, Ota E. Communication Tools Used in Cancer Communication with Children: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2022; 14(19):4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194624

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamaji, Noyuri, Daichi Suzuki, Maiko Suto, Kiriko Sasayama, and Erika Ota. 2022. "Communication Tools Used in Cancer Communication with Children: A Scoping Review" Cancers 14, no. 19: 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194624

APA StyleYamaji, N., Suzuki, D., Suto, M., Sasayama, K., & Ota, E. (2022). Communication Tools Used in Cancer Communication with Children: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 14(19), 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194624