Unresectable Ovarian Cancer Requires a Structured Plan of Action: A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Statistical Analysis

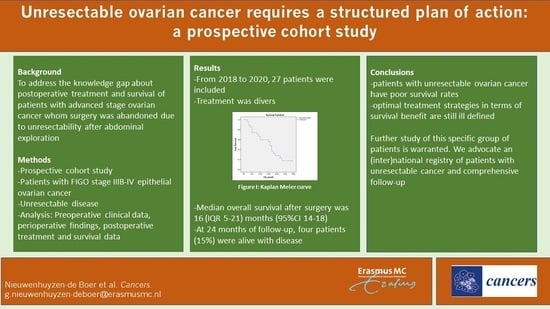

3. Results

3.1. Surgical Findings

3.2. Postoperative Treatment

3.3. Overall Survival

4. Discussion

4.1. CA-125

4.2. Overall Survival

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEOC | advanced-stage epithelial ovarian cancer |

| BRCA | breast cancer |

| CA | cancer antigen |

| CRS | cytoreductive surgery |

| CT | computerized tomography |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| NACT | neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| OS | overall survival |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PLD | pegylated liposomal doxorubicin |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SD | standard deviation |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Manning-Geist, B.L.; Hicks-Courant, K.; Gockley, A.A.; Clark, R.M.; Del Carmen, M.G.; Growdon, W.B.; Horowitz, N.S.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Muto, M.G.; Worley, M.J., Jr. A novel classification of residual disease after interval debulking surgery for advanced-stage ovarian cancer to better distinguish oncologic outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 326.e1–326.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogineni, V.; Morand, S.; Staats, H.; Royfman, R.; Devanaboyina, M.; Einloth, K.; Dever, D.; Stanbery, L.; Aaron, P.; Manning, L.; et al. Current Ovarian Cancer Maintenance Strategies and Promising New Developments. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Barroilhet, L.; Behbakht, K.; Berchuck, A.; Chen, L.M.; Cristea, M.; DeRosa, M.; Eisenhauer, E.L.; et al. Ovarian Cancer, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergote, I.; Coens, C.; Nankivell, M.; Kristensen, G.B.; Parmar, M.K.B.; Ehlen, T.; Jayson, G.C.; Johnson, N.; Swart, A.M.; Verheijen, R.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus debulking surgery in advanced tubo-ovarian cancers: Pooled analysis of individual patient data from the EORTC 55971 and CHORUS trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergote, I.; Tropé, C.G.; Amant, F.; Kristensen, G.B.; Ehlen, T.; Johnson, N.; Verheijen, R.H.M.; van der Burg, M.E.L.; Lacave, A.J.; Panici, P.B.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, G.M.; Hofhuis, W.; Reesink-Peters, N.; Ewing-Graham, P.C.; Schoots, I.G.; Beltman, J.J.; Piek, J.M.J.; Baalbergen, A.; Kooi, G.S.; van Haaften, A.; et al. Evaluation of effectiveness of the PlasmaJet surgical device in the treatment of advanced stage ovarian cancer (PlaComOv-study): Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, G.M.; Hofhuis, W.; Reesink-Peters, N.; Willemsen, S.; Boere, I.A.; Schoots, I.G.; Piek, J.M.J.; Hofman, L.N.; Beltman, J.J.; van Driel, W.J.; et al. Adjuvant Use of PlasmaJet Device During Cytoreductive Surgery for Advanced-Stage Ovarian Cancer: Results of the PlaComOv-study, a Randomized Controlled Trial in The Netherlands. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4833–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, F.; Nganga, E.C.; Dumas, L.; Banerjee, S.; Rockall, A.G. Imaging in the pre-operative staging of ovarian cancer. Abdom. Imaging 2018, 44, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBorley, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.; Yazbek, J.; Williamson, R.; Bharwani, N.; Stewart, V.; Carson, I.; Hird, E.; McIndoe, A.; Farthing, A.; et al. Radiological predictors of cytoreductive outcomes in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 122, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Cheng, S.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y. Roles of CA125 in diagnosis, prediction, and oncogenesis of ovarian cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-BBA 2021, 1875, 188503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaban, A.; Topuz, S.; Saip, P.; Sozen, H.; Salihoğlu, Y. In patients with advanced ovarian cancer, primary suboptimal surgery has better survival outcome than interval suboptimal surgery. J. Turk. Gynecol. Assoc. 2018, 20, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, A.E.; Everett, E.N.; Pastore, L.; Andersen, W.A.; Taylor, P.T., Jr. Predictors of suboptimal surgical cytoreduction in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer treated with initial chemotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2008, 18, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brons, P.E.; Boer, G.M.N.-D.; Ramakers, C.; Willemsen, S.; Kengsakul, M.; van Beekhuizen, H.J. Preoperative Cancer Antigen 125 Level as Predictor for Complete Cytoreduction in Ovarian Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study and Systematic Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Patel, S.M.; Arora, R.; Tiwari, R.; Dave, P.; Desai, A.; Mankad, M. Does preoperative CA-125 cutoff value and percent reduction in CA-125 levels correlate with surgical and survival outcome after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer?—Our experience from a tertiary cancer institute. South Asian J. Cancer 2020, 9, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, S.; Besic, N.; Drmota, E.; Kovacevic, N. Preoperative serum CA-125 level as a predictor for the extent of cytoreduction in patients with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2021, 55, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaba, F.; Ash, K.; Blyuss, O.; Bizzarri, N.; Kamfwa, P.; Ramirez, P.T.; Kotsopoulos, I.C.; Chandrasekaran, D.; Gomes, N.; Butler, J.; et al. Patient outcomes following interval and delayed cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer: Protocol for a multicenter, international, cohort study (Global Gynaecological Oncology Surgical Outcomes Collaborative). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti, A.; Ferrandina, M.G.; Vizzielli, G.; Pasciuto, T.; Fanfani, F.; Gallotta, V.; Margariti, P.A.; Chiantera, V.; Costantini, B.; Alletti, S.G.; et al. Randomized trial of primary debulking surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (SCORPION-NCT01461850). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, J.; Raja, F.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Colombo, N.; Sessa, C. Corrections to “Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up”. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 4), iv259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Age (Year) | BMI (kg/m2) | FIGO Stage | CA-125 (Diagnosis) (kU/L) | CA-125 (NACT) (kU/L) | WHO 1 | Dose Modification in NACT | Co-Morbidity 2 | Polypharmarcy 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | 47.9 | IIIC | 1715 | 98 | 2 | No | − | + |

| 2 | 65 | 20.7 | IIIC | 1681 | 599 | 2 | No | − | + |

| 3 | 72 | 24.5 | IIIC | 16,054 | 700 * | 0 | No | − | − |

| 4 | 60 | 21.8 | IIIC | 586 | 41 | 2 | No | − | − |

| 5 | 62 | 31.6 | IIIC | 581 | 377 | 1 | No | − | − |

| 6 | 81 | 22.5 | IIIC | 2703 | 180 | 1 | No | + | + |

| 7 | 80 | 17.2 | IIIC | 5198 | 1873 | 1 | No | − | − |

| 8 | 73 | 31.6 | IIIC | 1300 | 79 * | 1 | No | − | − |

| 9 | 76 | 22.9 | IV | 869 | 34 * | 0 | No | + | − |

| 10 | 64 | 21 | IV | 2688 | 37 * | 0 | No | − | − |

| 11 | 64 | 23.1 | IIIC | 220 | 98 | 1 | No | − | − |

| 12 | 76 | 19.8 | IIIC | 760 | 170 | - | No | − | − |

| 13 | 77 | 22 | IV | 130 | 81 | 0 | No | − | − |

| 14 | 75 | 19.5 | IV | 241 | 146 | 1 | Yes | + | + |

| 15 | 78 | 20.4 | IV | 1331 | 51 * | 0 | No | − | − |

| 16 | 76 | 18.8 | IV | 11,239 | 3695 | 2 | No | + | − |

| 17 | 74 | 22.3 | IV | 2532 | 40 * | 1 | No | + | − |

| 18 | 69 | 20.1 | IV | 237 | 27 | 1 | No | + | − |

| 19 | 61 | 22.5 | IIIC | 11,000 | 220 * | 0 | No | + | − |

| 20 | 76 | 30.7 | IV | 290 | 64 | 0 | Yes | − | − |

| 21 | 78 | 22.3 | IIIB | 526 | 13.3 * | 1 | No | − | − |

| 22 | 71 | 26.7 | IV | 550 | 38 | 0 | No | − | − |

| 23 † | 28 | 20 | IIIC | 120 | 74.9 | 1 | No | − | − |

| 24 | 58 | 29.4 | IIIC | 470 | 270 | 0 | No | − | + |

| 25 | 72 | 27.7 | IIIC | 310 | 250 | 1 | No | + | + |

| 26 | 68 | 33.6 | IV | 660 | 51 | 1 | No | − | − |

| 27 | 68 | 28.3 | IIIC | 649 | 77 | 1 | No | − | − |

| Patient | Description of Surgical Findings |

|---|---|

| 1 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and liver |

| 2 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 3 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, tumor lesions up to 10 cm entire bowel, bladder, liver, spleen, diaphragm. Involvement renal vein by enlarged para aortic lymph nodes. |

| 4 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, tumor lesions entire colon and small bowel, mesentery, liver, diaphragm, spleen, truncus coeliacus |

| 5 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, no access to pelvis after adhesiolysis |

| 6 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and liver |

| 7 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, no access to pelvis after adhesiolysis |

| 8 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 9 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, extensive tumor lesions in liver and spleen |

| 10 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and mesocolon |

| 11 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 12 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 13 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 14 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 15 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, all organs and block by adhesions |

| 16 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and mesocolon |

| 17 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery, mesocolon and stomach |

| 18 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 19 * | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 20 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery, liver and stomach |

| 21 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and liver, no access to pelvis after adhesiolysis |

| 22 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, extensive tumor lesions in spleen |

| 23 † | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions in colon and mesocolon, spleen, pancreas, vessels liver, vena cava inferior |

| 24 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery |

| 25 | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel, mesentery and liver |

| 26 | extensive tumor in peritoneum, mesentery and liver |

| 27 * | extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, extensive tumor lesions entire bowel and mesentery, all organs and block by adhesions, mass in mesentery extending to the superior mesenterial artery |

| Patient | Postoperative Treatment as Part of First-Line Treatment | Progression-Free Survival (Months) | 2nd and Subsequent Treatment Lines | Overall Survival (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | 2.9 | |

| 2 | TC | - | 3.8 | |

| 3 | TC | - | 3.9 | |

| 4 | TC | - | 4.5 | |

| 5 | TC | - | 5.1 | |

| 6 | TC | - | 5.4 | |

| 7 | TC | - | 5.7 | |

| 8 | TC maint bev | 6 | TC q3w (1 cycle) | 8.1 |

| 9 | TC | 3 | Wee1 kinase inhibitor and carboplatin (8 cycles) | 9.3 |

| 10 | TC | 7 | TC q3w | 10.2 |

| 11 | TC | 4 | PLD q4w- bev | 10.3 |

| 12 | - | 3 | - | 15.3 |

| 13 | TC | 7 15 | TC q3w TC (1 cycle) | 16.2 |

| 14 | TC | 8 | PLD q4w (1 cycle) | 16.9 |

| 15 | TC | 9 | TC, maint niraparib (3 weeks) | 17.1 |

| 16 | TC | 7 | paclitaxel weekly + bev, maint bev | 17.7 |

| 17 | - | 8 | TC weekly (2 cycles) | 17.7 |

| 18 | TC | 8 | paclitaxel weekly + bev, maint bev | 18.1 |

| 19 | TC | 13 | PLD/carboplatin q4w, maint olaparib | 19.0 |

| 20 | TC | 10 | PLD q4w | 22.4 |

| 21 | TC | 9 20 | TC weekly PLD q4w | 22.9 |

| 22 | cyclophosphamide/bev | 19 | carboplatin q3w (3 cycles) | 23.1 |

| 23 † | Letrozole | 18 | continuing letrozole | 31.5 |

| 24 | TC | 1 | Letrozole | alive with disease >24 months |

| 25 | TC | 13 28 | Cyclofosfamide + bev, maint bev PLD/carboplatin q4w | alive with disease >36 months |

| 26 | TC | 15 | TC, maint olaparib | alive with disease >33 months |

| 27 | TC | 8 17 21 | gemcitabine PLD q4w TC q3w | alive with disease >28 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, G.M.; Kengsakul, M.; Boere, I.A.; van Doorn, H.C.; van Beekhuizen, H.J. Unresectable Ovarian Cancer Requires a Structured Plan of Action: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010072

Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer GM, Kengsakul M, Boere IA, van Doorn HC, van Beekhuizen HJ. Unresectable Ovarian Cancer Requires a Structured Plan of Action: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cancers. 2023; 15(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleNieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, Gatske M., Malika Kengsakul, Ingrid A. Boere, Helena C. van Doorn, and Heleen J. van Beekhuizen. 2023. "Unresectable Ovarian Cancer Requires a Structured Plan of Action: A Prospective Cohort Study" Cancers 15, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010072

APA StyleNieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, G. M., Kengsakul, M., Boere, I. A., van Doorn, H. C., & van Beekhuizen, H. J. (2023). Unresectable Ovarian Cancer Requires a Structured Plan of Action: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cancers, 15(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010072