Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

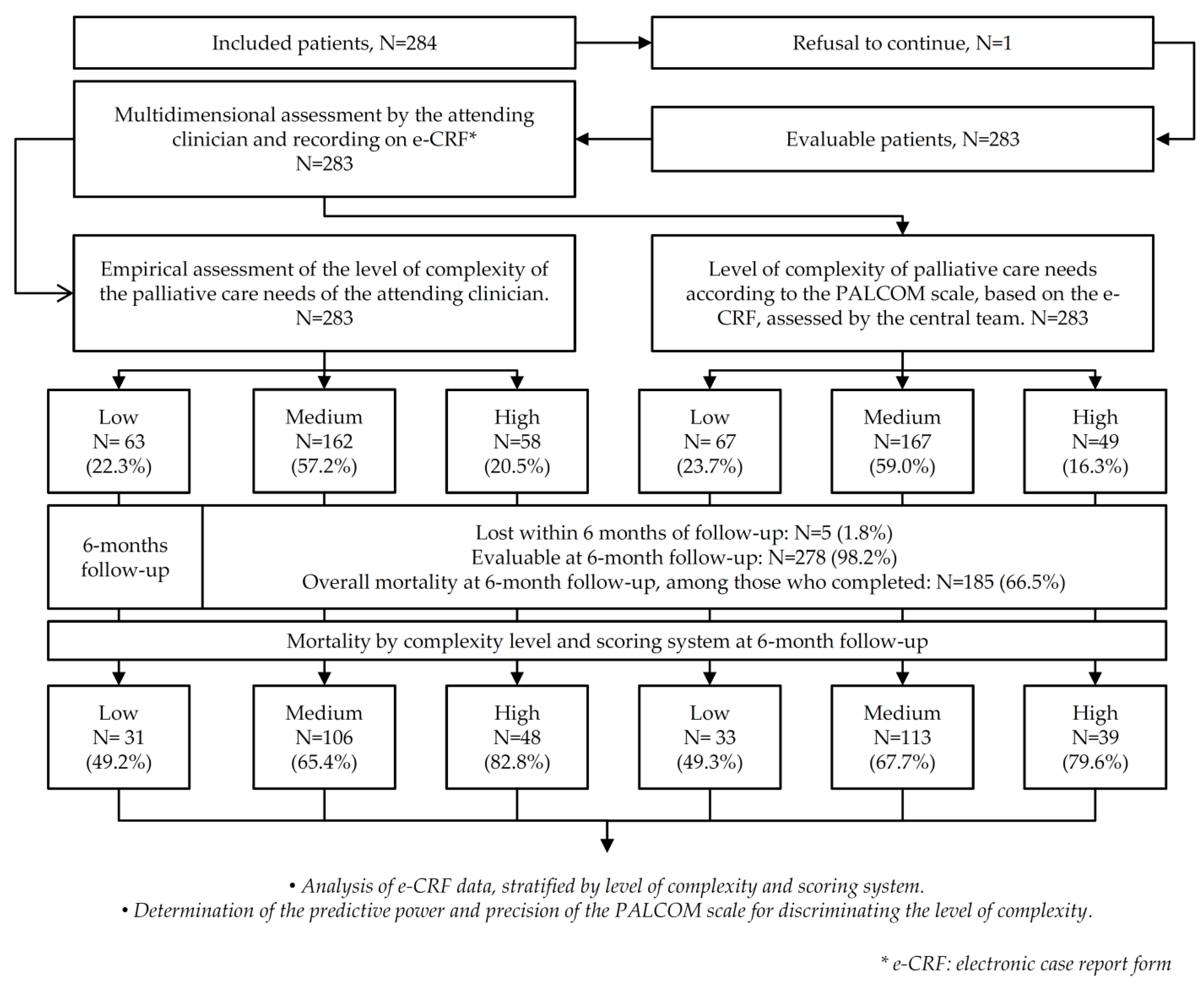

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Period and Setting

2.2. Objectives and Main Variables

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Empirical Assessment of the Level of Complexity

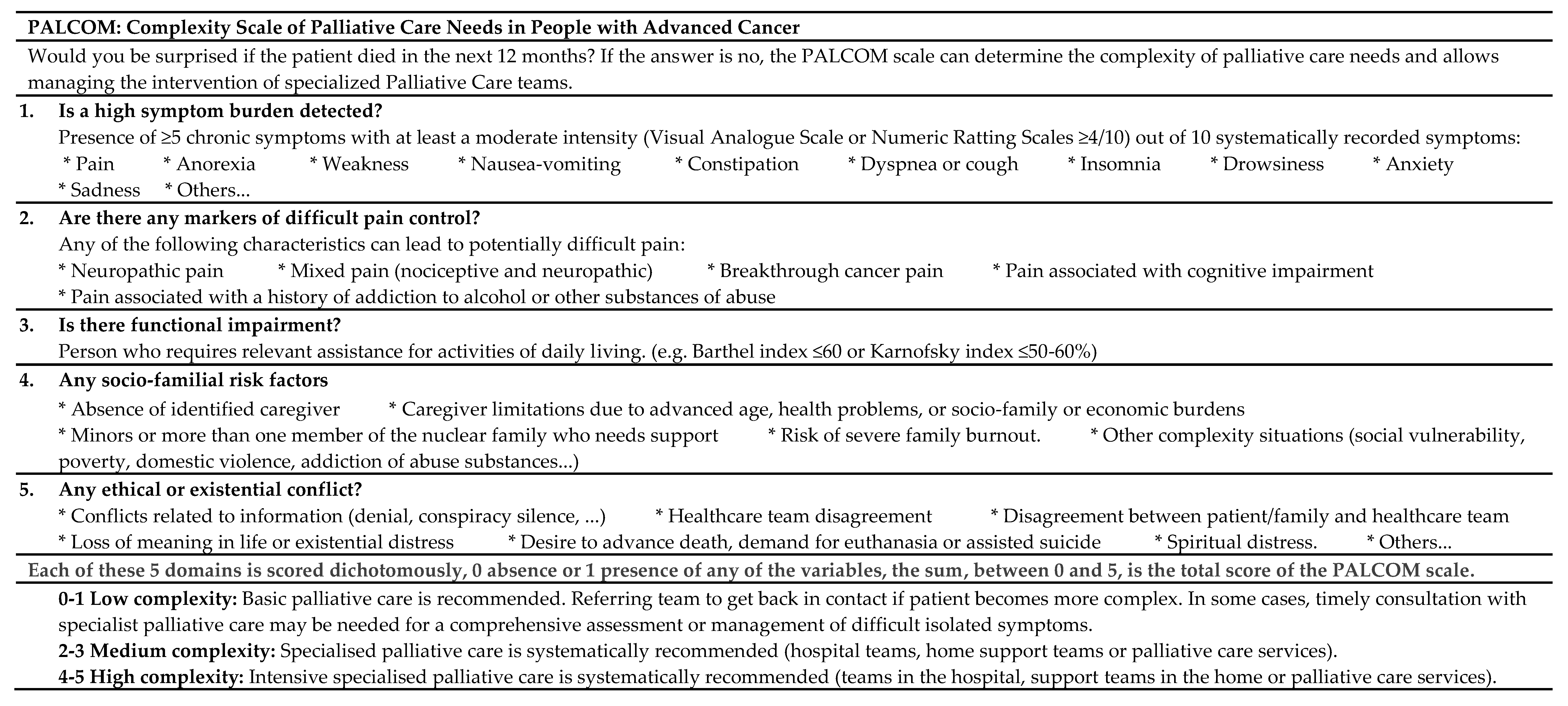

2.5. PALCOM Scale

2.6. Registry of the Multidimensional Assessment

2.7. Development of the Study

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results According to the Level of Complexity

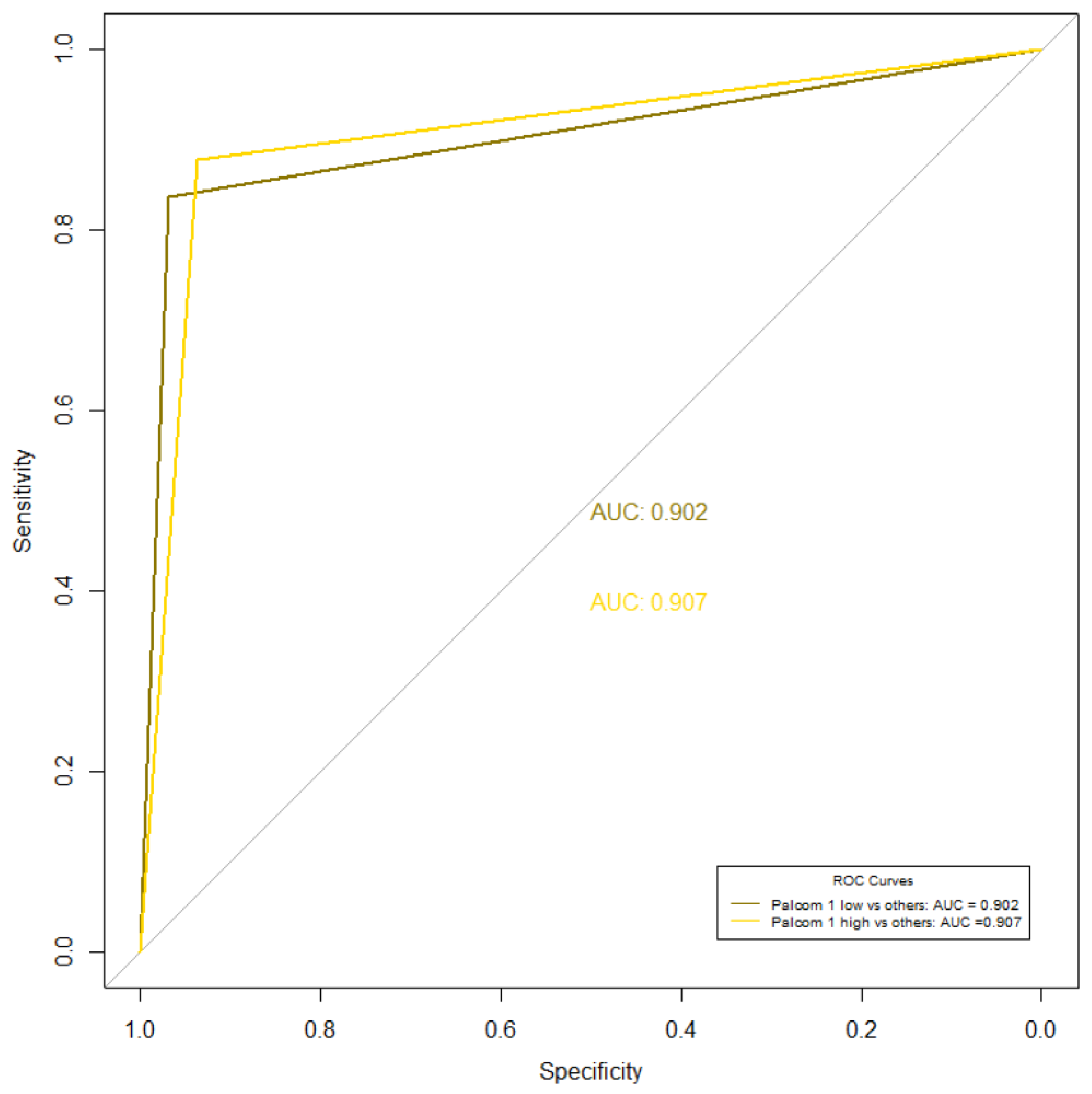

3.2. Correlation between the Empirical Assessment and the PALCOM Scale

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Practical implications:

- Research implications:

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Integrated Treatment throughout the Life Course. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2014, 28, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M.; Albreht, T.; Anderson, R.; Bruera, E.; Brunelli, C.; Caraceni, A.; Cervantes, A.; Currow, D.C.; et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e588–e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaul, F.M.; Farmer, P.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Kwete, X.J.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Alleyne, G.A.O.; et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—An imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Abernethy, A.P.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Ferrell, B.R.; Loscalzo, M.; Meier, D.E.; Paice, J.A.; et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines for lung cancer screening. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2015, 25, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, G.B.; Dzierżanowski, T.; Hauser, K.; Larkin, P.; Luque-Blanco, A.; Murphy, I.; Puchalski, C.; Ripamonti, C.; on behalf of theESMO Guidelines Committee. Care of the adult cancer patient at the end of life: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, S.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Padrone, L.; Martins-Welch, D. From evidence to practice: Early integration of palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2022, 31, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.A.; Tosteson, T.D.; Li, Z.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Hegel, M.T.; et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Breitbart, W.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.F.; Hassard, T.; Harlos, M. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Azuero, A.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Tosteson, T.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Akyar, I.; et al. Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyar, S.; Lesperance, M.; Shannon, R.; Sloan, J.; Colon-Otero, G. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: Results of a randomized pilot study. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, I.J.; Bausewein, C.; Reilly, C.C.; Gao, W.; Gysels, M.; Dzingina, M.; McCrone, P.; Booth, S.; Jolley, C.J.; Moxham, J. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudzen, C.R.; Richardson, L.D.; Johnson, P.N.; Hu, M.; Wang, B.; Ortiz, J.M.; Kistler, E.A.; Chen, A.; Morrison, R.S. Emergency Department-Initiated Palliative Care in Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, P.; Trauer, T.; Kelly, B.; O’Connor, M.; Thomas, K.; Summers, M.; Zordan, R.; White, V. Reducing the psychological distress of family caregivers of home-based palliative care patients: Short-term effects from a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitdehaag, M.J.; van Putten, P.G.; van Eijck, C.H.; Verschuur, E.M.; van der Gaast, A.; Pek, C.J.; van der Rijt, C.C.; de Man, R.A.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Laheij, R.J.; et al. Nurse-led follow-up at home vs. conventional medical outpatient clinic follow-up in patients with incurable upper gastrointestinal cancer: A randomized study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.; Sun, V.; Hurria, A.; Cristea, M.; Raz, D.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Reckamp, K.; Williams, A.C.; Borneman, T.; Uman, G.; et al. Interdisciplinary Palliative Care for Patients with Lung Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 50, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Jackson, V.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Lennes, I.T.; Heist, R.S.; Gallagher, E.R.; Temel, J.S. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T.; et al. Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.B.; Phillips, T.; Smith, T.J. Using the New ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline for Palliative Care Concurrent with Oncology Care Using the TEAM Approach. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2017, 37, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblum, R.E.; Rogal, S.S.; Park, E.R.; Impagliazzo, C.; Abdulhay, L.B.; Grosse, P.J.; Temel, J.S.; Arnold, R.M.; Schenker, Y. National Survey Using CFIR to Assess Early Outpatient Specialty Palliative Care Implementation. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2023, 65, e175–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, D.E.; Meier, D.E. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of early and systematic Integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltoni, M.; Scarpi, E.; Dall’Agata, M.; Zagonel, V.; Berte, R.; Ferrari, D.; Broglia, C.M.; Bortolussi, R.; Trentin, L.; Valgiusti, M.; et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 65, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochovska, S.; Ferreira, D.H.; Luckett, T.; Phillips, J.L.; Currow, D.C. Earlier multi-disciplinary palliative care intervention for people with lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; Beyer, F.; Sistermanns, J.; Kuon, J.; Kahl, C.; Alt-Epping, B.; Stevens, S.; Ahlborn, M.; George, C.; Heider, A.; et al. Symptom burden and palliative care needs of patients with incurable cancer at diagnosis and during the disease course. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1058–e1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, R.; Swami, N.; Pope, A.; Hui, D.; Hannon, B.; Le, L.W.; Zimmermann, C. Impact of early palliative care according to baseline symptom severity: Secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Bruera, E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Models of Palliative Care Delivery for Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Heung, Y.; Bruera, E. Timely Palliative Care: Personalizing the Process of Referral. Cancers 2022, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodiamont, F.; Jünger, S.; Leidl, R.; Maier, B.O.; Schildmann, E.; Bausewein, C. Understanding complexity—The palliative care situation as a complex adaptive system. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glouberman, S.; Zimmerman, B. Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of Medicare look like? Romanow Pap. 2002, 2, 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- Munday, D.F.; Johnson, S.A.; Griffiths, F.E. Complexity theory and palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 308–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Rosello, M.L.; Sanz-Amores, M.R.; Salvador-Comino, M.R. Instruments to evaluate complexity in end-of-life care. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 12, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.; de Graaf, E.; Teunissen, S. A systematic review of classifications systems to determine complexity of patient care needs in palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuca-Rodriguez, A.; Gómez-Batiste, X.; Espinosa-Rojas, J.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Codorniu, N.; Porta-Sales, J. Structure, organisation and clinical outcomes in cancer patients of hospital support teams in Spain. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 2, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuca, A.; Gómez-Martínez, M.; Prat, A. Predictive model of complexity in early palliative care: A cohort of advanced cancer patients (PALCOM study). Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Puchades-García, A.; Pérez-Ros, P. Accuracy of Delirium Screening Tools in Older People with Cancer-A Systematic Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.S.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D.G.; Ganguli, M.; Jeste, D.V.; Paulsen, J.S.; Petersen, R.C. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: The DSM-5 approach. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fainsinger, R.L.; Nekolaichuk, C.L. A “TNM” classification system for cancer pain: The Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain (ECS-CP). Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fainsinger, R.L.; Nekolaichuk, C.L.; Lawlor, P.G.; Neumann, C.M.; Hanson, J.; Vigano, A. A multicenter study of the revised Edmonton Staging System for classifying cancer pain in advanced cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2005, 29, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaus, S.; Crelier, B.; Donzé, J.D.; Aubert, C.E. Definition of patient complexity in adults: A narrative review. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, K.; Aapro, M.; Kaasa, S.; Ripamonti, C.I.; Scotté, F.; Strasser, F.; Young, A.; Bruera, E.; Herrstedt, J.; Keefe, D.; et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpi, E.; Dall’Agata, M.; Zagonel, V.; Gamucci, T.; Bertè, R.; Sansoni, E.; Amaducci, E.; Broglia, C.M.; Alquati, S.; on behalf of the Early Palliative Care Italian Study Group (EPCISG); et al. Systematic vs. on-demand early palliative care in gastric cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial assessing patient and healthcare service outcomes. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2425–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquet-Duran, X.; Jiménez-Zafra, E.M.; Manresa-Domínguez, J.M.; Tura-Poma, M.; Bosch-Delarosa, O.; Moragas-Roca, A.; Padilla, M.C.G.; Moreno, S.M.; Martínez-Losada, E.; Crespo-Ramírez, S.; et al. Describing complexity in palliative home care through HexCom: A cross-sectional, multicenter study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquet-Duran, X.; Jiménez-Zafra, E.M.; Tura-Poma, M.; Bosch-de la Rosa, O.; Moragas-Roca, A.; Martin-Moreno, S.; Martínez-Losada, E.; Crespo-Ramírez, S.; Lestón-Lado, L.; Salamero-Tura, N.; et al. Assessing Face Validity of the HexCom Model for Capturing Complexity in Clinical Practice: A Delphi Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquet-Duran, X.; Moreno-Gabriel, E.; Jiménez-Zafra, E.M.; Tura-Poma, M.; Bosch-DelaRosa, O.; Moragas-Roca, A.; Martin-Moreno, S.; Martínez-Losada, E.; Crespo-Ramírez, S.; Lestón-Lado, L.; et al. Gender and Observed Complexity in Palliative Home Care: A Prospective Multicentre Study Using the HexCom Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquet-Duran, X.; Manresa-Domínguez, J.M.; Llobera-Estrany, J.; López-García, A.I.; Moreno-Gabriel, E.; Toran-Monserrat, P. Care complexity and place of death in palliative home care. Gac Sanit. 2022, 37, 102266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, C.E.; Klug, D.; Campos, L.; Losekann, M.V.; Nunes, T.D.S.; Cruz, R.P. Analysis of the Perroca scale in palliative care unit. Rev. ESC Enferm. USP 2018, 52, e03305. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Gordon, R. The development of Version 2 of the AN-SNAP casemix classification system. Aust. Health Rev. 2007, 31 (Suppl. S1), S68–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Mori, M.; Watanabe, S.M.; Caraceni, A.; Strasser, F.; Saarto, T.; Cherny, N.; Glare, P.; Kaasa, S.; Bruera, E. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e552–e559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuca, A.; Viladot, M.; Barrera, C.; Chicote, M.; Casablancas, I.; Cruz, C.; Font, E.; Marco-Hernández, J.; Padrosa, J.; Pascual, A.; et al. Prevalence of ethical dilemmas in advanced cancer patients (secondary analysis of the PALCOM study). Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3667–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, S.; Martucci, G.; Autelitano, C.; Alquati, S.; Peruselli, C.; Artioli, G. Consultations’ demand for a hospital palliative care unit: How to increase appropriateness? Implementing and evaluating a multicomponent educational intervention aimed at increase palliative care complexity perception skill. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Comino, M.R.S.; Garcia, V.R.; López, M.A.F.; Feddersen, B.; Roselló, M.L.M.; Sanftenberg, L.; Schelling, J. Assessment of IDC-Pal as a Diagnostic Tool for Family Physicians to Identify Patients with Complex Palliative Care Needs in Germany: A Pilot Study. Gesundheitswesen 2018, 80, 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Zafra, M.I.; Gómez-García, R.; Ocaña-Riola, R.; Martín-Roselló, M.L.; Blanco-Reina, E. Level of Palliative Care Complexity in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Multinomial Logistic Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, G.; Videira-Silva, A.; Carrancha, M.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Complexity of patient care needs in palliative care: A scoping review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Romero, E.; Tallón-Martín, B.; García-Ruiz, M.P.; Puente-Fernandez, D.; García-Caro, M.P.; Montoya-Juarez, R. Frailty, Complexity, and Priorities in the Use of Advanced Palliative Care Resources in Nursing Homes. Medicina 2021, 57, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquet-Duran, X.; Esteban-Perez, M.; Manresa-Domínguez, J.M.; Moreno, S.M.; Leston-Lado, L.; Torán-Monserrat, P. Intra-rater reliability and feasibility of the HexCom advanced disease complexity assessment model. Atención Primaria 2022, 54, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N total | 283 | 100 | ||

| Gender | Men | 161 | 56.9 | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 71 (SD ± 59.0 − 81.0) | ||

| Primary cancer | Lung | 69 | 24.4 | |

| Colon | 56 | 19.8 | ||

| Prostate | 28 | 9.9 | ||

| Breast | 19 | 6.7 | ||

| Pancreas | 18 | 6.4 | ||

| Other origins (<5%) * | 93 | 32.8 | ||

| Cancer extension | Local and regional | 63 | 22.3 | |

| Metastases | 220 | 77.7 | ||

| Cancer treatment, last 4 weeks | Overall | 190 | 67.2 | |

| Chemotherapy ** | 135 | 47.7 | ||

| Radiotherapy | 26 | 12.7 | ||

| Hormonal therapy | 19 | 6.7 | ||

| Karnofsky index | ≤50% | 135 | 47.5 | |

| Symptoms prevalence | Asthenia | 269 | 95.1 | |

| Anorexia | 226 | 79.9 | ||

| Pain | 245 | 86.6 | ||

| Nausea | 68 | 24.0 | ||

| Constipation | 162 | 57.2 | ||

| Dyspnoea | 111 | 39.2 | ||

| Insomnia | 177 | 62.5 | ||

| Anxiety | 184 | 65.0 | ||

| Sadness | 196 | 69.3 | ||

| No well-being sense | 273 | 96.5 | ||

| High symptom burden | ≥5 symptoms with intensity in NRS ≥ 4. | 136 | 48.1 | |

| Pain characteristics | Type | Nociceptive somatic | 149 | 60.8 |

| Nociceptive visceral | 107 | 43.7 | ||

| Neuropathic | 73 | 29.8 | ||

| Difficult pain according ECS-CP *** | 166 | 58.5 | ||

| Breakthrough pain | 135 | 55.1 | ||

| Psychological distress | 64 | 26.1 | ||

| Addictive behaviour | 20 | 8.2 | ||

| Cognitive impairment | 26 | 9.3 | ||

| Mixed pain **** | 73 | 29.8 | ||

| Social risk factors according PALCOM scale | 184 | 64.8 | ||

| Existential/ethical problems according PALCOM scale | 67 | 23.6 | ||

| Professional Empirical Assessment N (%) | PALCOM Scale N (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | ||||

| N total = 283 | 63 (22.3) | 162 (57.2) | 58 (20.5) | 67 (23.7) | 167 (59.0) | 49 (17.3) | |||

| Gender: Men | 40 (63.5) | 92 (56.8) | 29 (50.0) | 41 (61.2) | 97 (58.1) | 23 (46.9) | |||

| Cancer treatment last 4 weeks | 36 (57.1) | 91 (56.2) | 23 (39.7) | 41 (61.2) | 87 (52.1) | 22 (44.9) | |||

| Symptom prevalence | p | p | |||||||

| Asthenia | 57 (90.5) | 154 (95.1) | 58 (100) | <0.0001 | 62 (92.5) | 158 (94.6) | 49 (100) | <0.0001 | |

| Anorexia | 40 (63.5) | 134 (82.7) | 52 (89.7) | <0.0001 | 45 (67.2) | 137 (82.0) | 44 (89.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Pain | 50 (79.4) | 140 (86.4) | 53 (91.4) | <0.0001 | 54 (80.6) | 140 (83.8) | 49 (100) | <0.0001 | |

| Nausea | 10 (15.9) | 37 (22.8) | 21 (36.2) | 0.032 | 11 (16.4) | 35 (21.0) | 22 (44.9) | 0.007 | |

| Constipation | 25 (39.7) | 95 (58.4) | 42 (72.4) | 0.003 | 28 (41.8) | 98 (58.7) | 36 (73.5) | <0.0001 | |

| Dyspnoea | 16 (25.4) | 61 (37.7) | 34 (58.6) | 0.017 | 18 (26.9) | 62 (37.1) | 31 (63.3) | 0.004 | |

| Insomnia | 27 (42.9) | 106 (65.4) | 44 (75.9) | <0.0001 | 30 (44.8) | 107 (64.1) | 40 (81.6) | <0.0001 | |

| Anxiety | 24 (38.1) | 114 (70.4) | 46 (79.3) | <0.0001 | 30 (44.8) | 111 (66.5) | 43 (87.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Sadness | 34 (54.0) | 116 (71.6) | 46 (79.3) | <0.0001 | 35 (52.2) | 117 (70.1) | 44 (89.8) | <0.0001 | |

| No well-being sense | 61 (96.7) | 157 (96.1) | 55 (94.8) | <0.0001 | 66 (98.5) | 161 (96.4) | 46 (93.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Karnofsky index ≤ 50% | 6 (9.5) | 81 (49.7) | 48 (82.8) | <0.0001 | 4 (6.0) | 90 (53.6) | 41 (83.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Factors of social-family risk | 17 (27.0) | 117 (71.9) | 50 (86.2) | <0.0001 | 13 (19.4) | 126 (75.0) | 45 (91.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Existential/ethical problems | 8 (12.7) | 33 (20.2) | 26 (44.8) | <0.0001 | 4 (6.0) | 34 (20.2) | 29 (59.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Professional Empirical Assessment N (%) | PALCOM Scale N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | p | |

| N total = 283 | 63 (22.3) | 162 (57.2) | 58 (20.5) | 67 (23.7) | 167 (59.0) | 49 (17.3) | NSD |

| PALCOM domains | |||||||

| 6 (9.5) | 85 (52.5) | 45 (77.6) | 6 (9.0) | 83 (49.7) | 47 (95.9) | <0.001 |

| 29 (46.0) | 91 (55.8) | 46 (79.3) | 30 (44.8) | 93 (55.4) | 43 (87.8) | <0.001 | |

| 6 (9.5) | 81 (49.7) | 48 (82.8) | 4 (6.0) | 90 (53.6) | 41 (83.7) | <0.001 | |

| 17 (27.0) | 117 (71.8) | 50 (86.2) | 13 (19.4) | 126 (75.0) | 45 (91.8) | <0.001 | |

| 8 (12.7) | 33 (20.2) | 26 (44.8) | 4 (6.0) | 34 (20.2) | 29 (59.2) | <0.001 | |

| Death before 6 months of follow-up. N = 185 (65.4) | 31 (49.2) | 106 (65.4) | 48 (82.8) | 33 (49.3) | 113 (67.7) | 39 (79.6) | <0.001 |

| Lost within 6 months of follow-up. N = 5 (1.8) | 0 | 5 (3.0) | 0 | 2 (2.9) | 3 (1.8) | 0 | - |

| Hospital death | 5 (16.1) | 26 (24.5) | 12 (25) | 6 (18.2) | 25 (22.1) | 12 (30.8) | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viladot, M.; Gallardo-Martínez, J.-L.; Hernandez-Rodríguez, F.; Izcara-Cobo, J.; Majó-LLopart, J.; Peguera-Carré, M.; Russinyol-Fonte, G.; Saavedra-Cruz, K.; Barrera, C.; Chicote, M.; et al. Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers 2023, 15, 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164182

Viladot M, Gallardo-Martínez J-L, Hernandez-Rodríguez F, Izcara-Cobo J, Majó-LLopart J, Peguera-Carré M, Russinyol-Fonte G, Saavedra-Cruz K, Barrera C, Chicote M, et al. Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2023; 15(16):4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164182

Chicago/Turabian StyleViladot, Margarita, Jose-Luís Gallardo-Martínez, Fany Hernandez-Rodríguez, Jessica Izcara-Cobo, Josep Majó-LLopart, Marta Peguera-Carré, Giselle Russinyol-Fonte, Katia Saavedra-Cruz, Carmen Barrera, Manoli Chicote, and et al. 2023. "Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients" Cancers 15, no. 16: 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164182

APA StyleViladot, M., Gallardo-Martínez, J.-L., Hernandez-Rodríguez, F., Izcara-Cobo, J., Majó-LLopart, J., Peguera-Carré, M., Russinyol-Fonte, G., Saavedra-Cruz, K., Barrera, C., Chicote, M., Barreto, T.-D., Carrera, G., Cimerman, J., Font, E., Grafia, I., Llavata, L., Marco-Hernandez, J., Padrosa, J., Pascual, A., ... Tuca, A. (2023). Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers, 15(16), 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164182