Disparities in Receipt of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline-Adherent Care and Outcomes among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Insurance Type

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

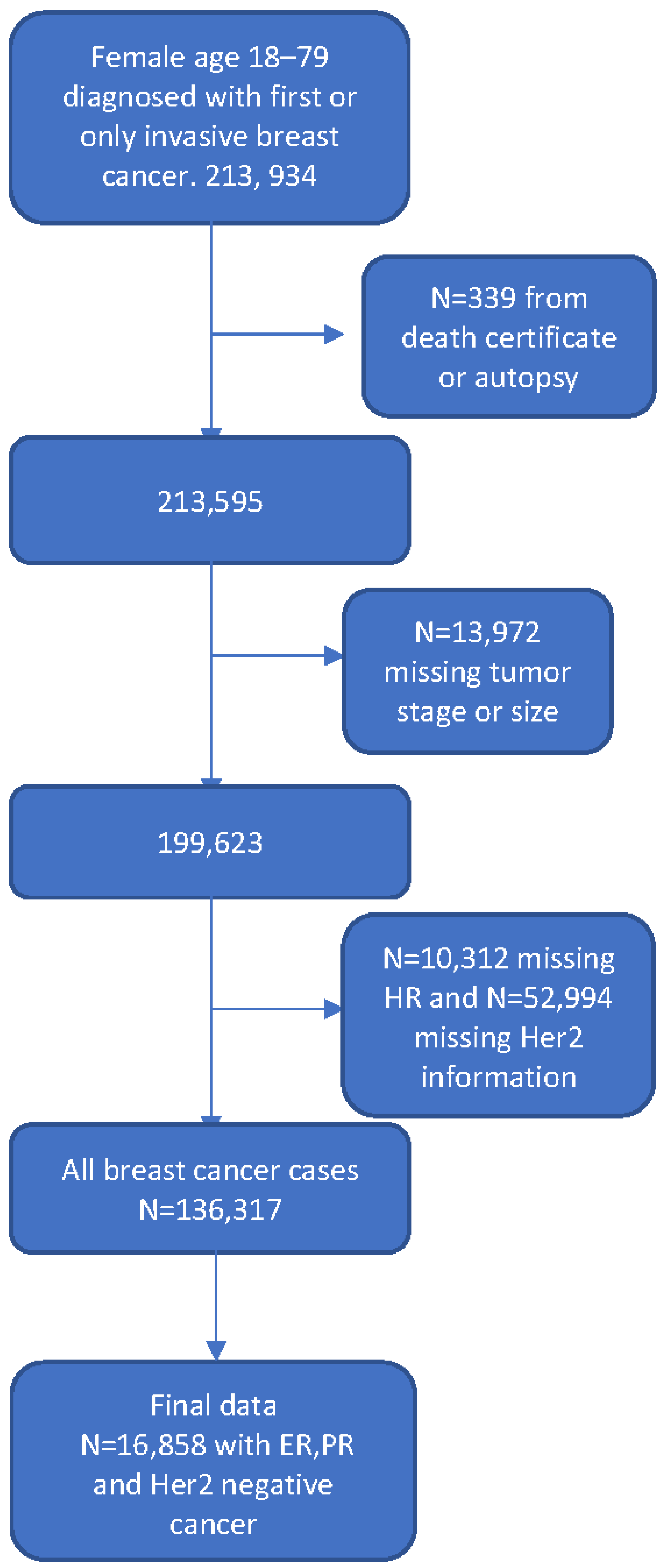

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

- Patients with localized disease and up to 1–3 positive lymph nodes (stages I, II, IIIA + N1) with node-negative tumors ≤ 10 mm who received sentinel lymph node surgery and either a total mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery (BCS) plus radiation.

- Patients with localized disease and up to 1–3 positive lymph nodes (stages I, II, IIIA + N1) with node-negative tumors > 10 mm who underwent sentinel lymph node surgery, chemotherapy, and either a total mastectomy or BCS plus radiation.

- Patients with localized disease and up to 1–3 positive lymph nodes (stages I, II, IIIA + N1) with nodal micro-metastasis, tumor ≤ 10 mm, who received sentinel lymph node surgery and either a total mastectomy or BCS plus radiation.

- Patients with localized disease and up to 1–3 positive lymph nodes (stages I, II, IIIA + N1) with nodal micro-metastasis, tumor > 10 mm, who received sentinel lymph node surgery, chemotherapy and either a total mastectomy or BCS plus radiation.

- Patients with localized disease and up to 1–3 positive lymph nodes (stages I, II, IIIA + N1) with lymph-node-positive tumors of any size who received sentinel lymph node surgery and chemotherapy.

- Patients with stages IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC tumors who received sentinel lymph node surgery and chemotherapy.

- Patients with stage IV cancer who received chemotherapy.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeSantis, C.E.; Ma, J.; Gaudet, M.M.; Newman, L.A.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. 2019, 69, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. C. S. W. Group. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Breastcancer.org. 2023. Available online: https://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/understand_bc/statistics#:~:text=About%201%20in%208%20U.S.,(in%20situ)%20breast%20cancer (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Luis, I.; Ottesen, R.A.; Hughes, M.E.; Mamet, R.; Burstein, H.J.; Edge, S.B.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Moy, B.; Rugo, H.S.; Theriault, R.L.; et al. Outcomes by tumor subtype and treatment pattenr in women with small, node negative breast cancer: A multi-institutional study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.; Smith, D.; Wolf, E.; Anderson, M. Racial disparities in cancer therapy: Did the gap narrow between 1992 and 2002? Cancer 2008, 112, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatoi, I.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. The Emergence of the Racial Dsiparity in U.S. Breast-Cancer Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2349–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, L.J.; Jiang, R.; Ward, K.C.; Gogineni, K.; Subhedar, P.D.; Sherman, M.E.; Gaudet, M.M.; Breitkopf, C.R.; D’angelo, O.; Gabram-Mendola, S.; et al. Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Outcomes in the Metropolitan Atlanta Area: New Insights and Approaches for Health Equity. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 3, pkz053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.; Han, Y.; Lian, M.; Colditz, G.A.; Weber, J.D.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Racial/Ethnic Differences in Treatment and Mortality Among Women With Triple Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA 2021, 7, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhani, S.S.; Bouz, A.; Stavros, S.; Zucker, I.; Tercek, A.; Chung-Bridges, K. Racial and Ethnic inequality in Survival Outcomes of Women With Triple Negative Brreast Cancer. Cureus 2022, 14, e27120. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Schupp, C.; Harrati, A.; Clarke, C.; Keegan, T.; Gomez, S. Developing an Area-Based Socioeconomic Measure from American Community Survey Data; Cancer Prevention Institute of California: Fremont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R.; Edge, S. Update: NCCN breast cancer clinical practice guidelines. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2004, 2 (Suppl. S3), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R.; McCormick, B. Update: NCCN breast cancer clinical practice guidelines. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2005, 3 (Suppl. S1), S7–S11. [Google Scholar]

- Gradishar, W.; Salerno, K. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Breast Cancer. 2016. Available online: https://education.nccn.org/system/files/Gradishar%26Salerno_NCCNac16_2upARS.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- N. C. C. Network. 2013. Available online: http://www.24hmb.com/voimages/web_image/upload/file/20140422/72881398143429924.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- N. G. V. 4. I. B. Cancer. NCCN.ORG. 2022. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Patrick, J.; Hasse, M.; Feinglass, J.; Khan, S. Trends in adherence to NCCN guidelines for breast conserving therapy in women with stage I and II breast cancer: Analysis of the 1998–2008 National Cancer Database. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 26, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, E.; Hussain, L.; Grannan, K.; Dunki-Jacobs, E.; Lee, D.; Wexelman, B. Racial disparities in breast cancer persist despite early detection: Analysis of treatment of stage 1 breast cancer and effect of insurance status on disparities. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 173, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojinnaka, C.; Luo, W.; Ory, M.; McMaughan, D.; Bolin, J. Disparities in surgical treatment of early-stage breast cancer among female residents of Texas: The role of racial residential segregation. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Del Rosario, M.; Chang, J.; Ziogas, A.; Jafari, M.D.; Bristow, R.E.; Tanjasiri, S.P.; Zell, J.A. Population-Based Analysis of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guideline Adherence for Patients with Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in California. Cancers 2023, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. Age and the Cardiovascular System. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 327, 1735–1739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.K.H.; Ang, J.J.; Tan, J.K.H.; Chia, D.K.A. Age is an independent risk factor for increased morbidity in electivee colorectal cancer surgery deespite an ERAS protocol. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2020, 405, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, T.H.M.; Parsons, H.M.; Chen, Y.; Maguire, F.B.; Morris, C.R.; Parikh-Patel, A.; Kizer, K.W.; Wun, T. Impact of Health Insurance on Stage at Cancer Diagnosis Among Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balfour, J.; Kaplan, G. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: Evidence from the alameda county study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 155, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Robert, S. The contributions of race, individual socioeconomic status, and neighborhood socioeconomic context on the self-rated health trajectories and mortality of older adults. Res. Aging 2008, 30, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, R.A. Race, Economics, and Social Status. 2018. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2018/race-economics-and-social-status/pdf/race-economics-and-social-status.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- U. B. o. L. a. Statistics. BLS Reports. 2019. Available online: www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2018/home (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Gee, G.; Payne-Sturges, D. Environmental Health Disparities: A Framework Integrating Psychosocial and Environmental Concepts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Story, M.; Nelson, M. Neighborhood Environments: Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, N.; Dubowitz, T. Health Disparities and Access to Care. JAMA 2007, 297, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Means, S.; Osmani, A. Affordable care act and disparities in health services utilization among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors: Evidence from longitudinal medical expenditure panel surveys 2008–2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1860–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R.; He, Y.; Winer, E.; Keating, N. Trends in racial and age disparities in definitive local therapy of early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Kasl, S.; Howe, C.; Lachman, M.; Dubrow, R. African-American/White differences in breast carcinoma: p53 alterations and other tumor characteristics. Cancer 2004, 101, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks-Santi, L.J.; Barley, B.; Winchester, D.; Sultan, D.; McDonald, J.; Kanaan, Y.; Pearson-Fields, A.; Sutton, A.L.; Sheppard, V.; Williams, C. Affluence Does Not Influence Breast Cancer Outcomes in African American Women. J. Healthc. Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantz, P.M.; Mujahid, M.; Schwartz, K.; Janz, N.K.; Fagerlin, A.; Salem, B.; Liu, L.; Deapen, D.; Katz, S.J. The influence of race, ethnicity, and individual socioeconomic factors on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 2173–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hance, K.; Anderson, W.; Devesa, S.; Young, H.; Levine, P. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the national cancer institute. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, J.; Ganpat, M.; Kanaan, Y.; Fackler, M.; McVeigh, M. Lahti-Domenici and et al. Estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor-negative breast cancers of young african-american women have a high frequency of methylation of multiple genes than those of caucasians. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 2052–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. S. C. Bureau. 2020 Census: Racial and Ethnic Diversity Index by State. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2021/dec/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-index.html (accessed on 11 November 2022).

| Total N | % | NCCN-Adherent N | % | NCCN-Non-Adherent N | % | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16,858 | 100 | 5472 | 32.5 | 11,385 | 67.5 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 18–44 | 3533 | 21 | 1161 | 32.9 | 2372 | 67.1 | |

| 45–54 | 4568 | 27 | 1526 | 33.4 | 3042 | 66.6 | |

| 55–64 | 4594 | 27.3 | 1587 | 34.5 | 3007 | 65.5 | |

| 65+ | 4163 | 24.7 | 1198 | 28.8 | 2965 | 71.2 | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 2004–2009 | 10,193 | 60.5 | 3091 | 30.3 | 7102 | 69.7 | |

| 2010+ | 6665 | 39.5 | 2381 | 35.7 | 4284 | 64.3 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8930 | 53.0 | 3037 | 34.0 | 5893 | 66.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2085 | 12.4 | 605 | 29.0 | 1480 | 71.0 | |

| Hispanic | 3880 | 23.0 | 1175 | 30.3 | 2705 | 70.0 | |

| Asian | 1752 | 10.4 | 573 | 32.7 | 1179 | 67.3 | |

| Other/unknown | 211 | 1.3 | 82 | 38.9 | 129 | 61.1 | |

| Insurance | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Managed care | 8610 | 51.1 | 2887 | 33.5 | 5723 | 66.5 | |

| Medicare | 2688 | 15.9 | 791 | 29.4 | 1897 | 70.6 | |

| Medicaid | 2093 | 12.4 | 645 | 30.8 | 1448 | 69.2 | |

| Other insurance (FFS, Tricare, VA or NOS) | 2884 | 17.1 | 971 | 33.7 | 1913 | 66.3 | |

| Not insured or unknown | 583 | 3.5 | 178 | 30.5 | 405 | 69.5 | |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Lowest SES | 2590 | 15.4 | 723 | 27.9 | 1867 | 72.1 | |

| Lower-middle SES | 3207 | 19.0 | 998 | 31.1 | 2209 | 68.9 | |

| Middle SES | 3501 | 20.8 | 1109 | 31.7 | 2392 | 68.3 | |

| Higher-middle SES | 3800 | 22.5 | 1331 | 35.0 | 2469 | 65.0 | |

| Highest SES | 3760 | 22.3 | 1311 | 34.9 | 2449 | 65.1 | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married | 9838 | 58.4 | 3348 | 34.0 | 6490 | 66.0 | |

| Not married | 7020 | 41.6 | 2124 | 30.3 | 4896 | 69.7 | |

| Tumor stage | <0.0001 | ||||||

| I | 5737 | 34.0 | 2402 | 41.9 | 3335 | 58.1 | |

| II | 7800 | 46.3 | 1688 | 21.6 | 6112 | 78.4 | |

| III | 2645 | 15.7 | 819 | 31.0 | 1826 | 69.0 | |

| IV | 676 | 4.0 | 563 | 83.3 | 113 | 16.7 |

| Unadjusted OR (95% C.I.) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% C.I.) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.994 (0.991–0.997) | <0.0001 | 0.988 (0.984–0.991) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.79 (0.72–0.88) | <0.0001 | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | <0.0001 | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 0.003 |

| Asian | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) | 0.292 | 0.92 (0.82–1.03) | 0.14 |

| Other/unknown | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) | 0.14 | 1.29 (0.96–1.73) | 0.09 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Managed care | Ref | Ref | ||

| Medicare | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | <0.0001 | 0.92 (0.83–1.03) | 0.16 |

| Medicaid | 0.88 (0.80–0.98) | 0.02 | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 0.57 |

| Other insurance | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.89 | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.54 |

| Not insured or unknown | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 0.14 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 0.27 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||

| Highest SES | Ref | Ref | ||

| Lowest SES | 0.72 (0.65–0.81) | <0.0001 | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | <0.0001 |

| Lower-middle SES | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | 0.0009 | 0.88 (0.79–0.98) | 0.02 |

| Middle SES | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.004 | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | 0.07 |

| Higher-middle SES | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.88 | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.61 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | Ref | Ref | ||

| Married | 1.19 (1.11–1.27) | <0.0001 | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| I | Ref | Ref | ||

| II | 0.38 (0.36–0.41) | <0.0001 | 0.37 (0.34–0.40) | <0.0001 |

| III | 0.62 (0.57–0.69) | <0.0001 | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) | <0.0001 |

| IV | 6.92 (5.61–8.52) | <0.0001 | 7.47 (6.04–9.24) | <0.0001 |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% C.I.) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.997 (0.994–1.0) | 0.064 | 1.003 (1.0–1.006) | 0.06 |

| Year of Diagnosis | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.002 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.007 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.53 (1.39–1.68) | <0.0001 | 1.28 (1.16–1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 1.17 (1.07–1.27) | 0.001 | 0.96 (0.88–1.06) | 0.42 |

| Asian | 0.85 (0.75–0.97) | 0.014 | 0.83(0.73–0.95) | 0.001 |

| Other/unknown | 0.88 (0.62–1.24) | 0.46 | 0.78 (0.55–1.11) | 0.17 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Managed care | Ref | Ref | ||

| Medicare | 1.33 (1.21–1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) | 0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1.78 (1.61–1.96) | <0.0001 | 1.29 (1.16–1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Other insurance | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | 0.07 | 0.94 (0.85–1.04) | 0.25 |

| Not insured or unknown | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 0.002 | 1.17 (0.98–1.40) | 0.08 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||

| Highest SES | Ref | Ref | ||

| Lowest SES | 1.62 (1.45–1.82) | <0.0001 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.004 |

| Lower-middle SES | 1.44 (1.29–1.61) | <0.0001 | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | 0.004 |

| Middle SES | 1.36 (1.22–1.52) | <0.0001 | 1.21 (1.08–1.35) | 0.001 |

| Higher-middle SES | 1.17 (1.05–1.31) | 0.005 | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 0.33 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | Ref | |||

| Married | 0.77 (0.72–0.83) | <0.0001 | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 0.10 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| I | Ref | Ref | ||

| II | 2.83 (2.52–3.18) | <0.0001 | 2.59 (2.30–2.92) | <0.0001 |

| III | 9.03 (8.02–10.18) | <0.0001 | 8.28 (7.34–9.35) | <0.0001 |

| IV | 37.09 (32.37–42.50) | <0.0001 | 37.82 (32.74–43.68) | <0.0001 |

| Received NCCN-adherent care | ||||

| Yes | Ref | |||

| No | 1.15 (1.07–1.23) | 0.0002 | 1.21 (1.11–1.31) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ubbaonu, C.D.; Chang, J.; Ziogas, A.; Mehta, R.S.; Kansal, K.J.; Zell, J.A. Disparities in Receipt of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline-Adherent Care and Outcomes among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Insurance Type. Cancers 2023, 15, 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235586

Ubbaonu CD, Chang J, Ziogas A, Mehta RS, Kansal KJ, Zell JA. Disparities in Receipt of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline-Adherent Care and Outcomes among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Insurance Type. Cancers. 2023; 15(23):5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235586

Chicago/Turabian StyleUbbaonu, Chimezie D., Jenny Chang, Argyrios Ziogas, Rita S. Mehta, Kari J. Kansal, and Jason A. Zell. 2023. "Disparities in Receipt of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline-Adherent Care and Outcomes among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Insurance Type" Cancers 15, no. 23: 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235586

APA StyleUbbaonu, C. D., Chang, J., Ziogas, A., Mehta, R. S., Kansal, K. J., & Zell, J. A. (2023). Disparities in Receipt of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline-Adherent Care and Outcomes among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Insurance Type. Cancers, 15(23), 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235586