Influence of Sex and Age on Site of Onset, Morphology, and Site of Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study on Data from Four Italian Cancer Registries

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Metastasis

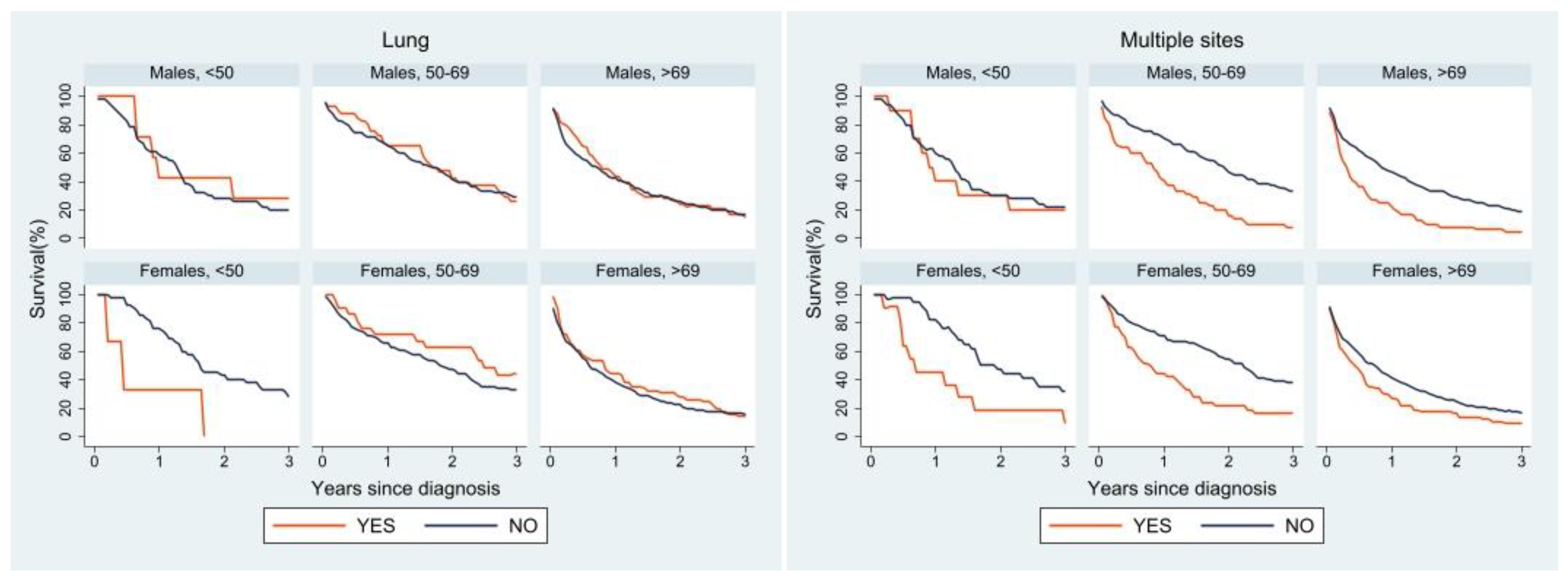

3.3. Survival

4. Discussion

Metastasis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- AIRTUM; AIOM. I Numeri Del Cancro in Italia; Intermedia Editore, Ed.; AIRTUM: Rome, Italy; AIOM: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barzi, A.; Lenz, A.M.; Labonte, M.J.; Lenz, H.J. Molecular Pathways: Estrogen Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5842–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maingi, J.W.; Tang, S.; Liu, S.; Ngenya, W.; Bao, E. Targeting Estrogen Receptors in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4087–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendifar, A.; Yang, D.; Lenz, F.; Lurje, G.; Pohl, A.; Lenz, C.; Yan, N.; Wu, Z.; Lenz, H.J. Gender Disparities in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6391–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matarrese, P.; Mattia, G.; Pagano, M.T.; Pontecorvi, G.; Ortona, E.; Malorni, W.; Carè, A. The Sex-Related Interplay between Time and Cancer: On the Critical Role of Estrogen, Micrornas and Autophagy. Cancers 2021, 13, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.; Ironmonger, L.; Steele, R.J.C.; Ormiston-Smith, N.; Crawford, C.; Seims, A. A Review of Sex-Related Differences in Colorectal Cancer Incidence, Screening Uptake, Routes to Diagnosis, Cancer Stage and Survival in the UK. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenner, H.; Kloor, M.; Pox, C.P. Colorectal Cancer. Lancet 2014, 383, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; DiLeo, A.; Niv, Y.; Gustafsson, J.Å. Estrogen Receptor Beta as Target for Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Cancer Lett. 2016, 372, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clocchiatti, A.; Cora, E.; Zhang, Y.; Dotto, G.P. Sexual Dimorphism in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Majek, O.; Gondos, A.; Jansen, L.; Emrich, K.; Holleczek, B.; Katalinic, A.; Nennecke, A.; Eberle, A.; Brenner, H. Sex Differences in Colorectal Cancer Survival: Population-Based Analysis of 164,996 Colorectal Cancer Patients in Germany. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Ren, S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F. Gender Differences in Colorectal Cancer Survival: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, R.; Sant, M.; Coleman, M.P.; Francisci, S.; Baili, P.; Pierannunzio, D.; Trama, A.; Visser, O.; Brenner, H.; Ardanaz, E.; et al. Cancer Survival in Europe 1999–2007 by Country and Age: Results of EUROCARE-5-a Population-Based Study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawa, T.; Kato, J.; Kawamoto, H.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Kohno, H.; Endo, H.; Shiratori, Y. Differences between Right- and Left-Sided Colon Cancer in Patient Characteristics, Cancer Morphology and Histology. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.Y.; Lai, M.D. Colorectal Cancer, One Entity or Three. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2009, 10, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, G.H.; Malietzis, G.; Askari, A.; Bernardo, D.; Al-Hassi, H.O.; Clark, S.K. Is Right-Sided Colon Cancer Different to Left-Sided Colorectal Cancer?—A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Lopez, N.E.; Eisenstein, S.; Schnickel, G.T.; Sicklick, J.K.; Ramamoorthy, S.L.; Clary, B.M. Synchronous Metastatic Colon Cancer and the Importance of Primary Tumor Laterality – A National Cancer Database Analysis of Right- versus Left-Sided Colon Cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 220, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamfjord, J.; Myklebust, T.Å.; Larsen, I.K.; Kure, E.H.; Glimelius, B.; Guren, T.K.; Tveit, K.M.; Guren, M.G. Survival Trends of Right- and Left-Sided Colon Cancer across Four Decades: A Norwegian Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2022, 31, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.M.; Pfau, P.R.; O’Connor, E.S.; King, J.; LoConte, N.; Kennedy, G.; Smith, M.A. Mortality by Stage for Right- versus Left-Sided Colon Cancer: Analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare Data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4401–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamashita, S.; Brudvik, K.W.; Kopetz, S.E.; Maru, D.; Clarke, C.N.; Passot, G.; Conrad, C.; Chun, Y.S.; Aloia, T.A.; Vauthey, J.N. Embryonic Origin of Primary Colon Cancer Predicts Pathologic Response and Survival in Patients Undergoing Resection for Colon Cancer Liver Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamas, K.; Walenkamp, A.M.E.; de Vries, E.G.E.; van Vugt, M.A.T.M.; Beets-Tan, R.G.; van Etten, B.; de Groot, D.J.A.; Hospers, G.A.P. Rectal and Colon Cancer: Not Just a Different Anatomic Site. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015, 41, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abancens, M.; Bustos, V.; Harvey, H.; McBryan, J.; Harvey, B.J. Sexual Dimorphism in Colon Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 607909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ji, L.; Zhu, J.; Mao, X.; Sheng, S.; Hao, S.; Xiang, D.; Guo, J.; Fu, G.; Huang, M.; et al. Lymph Node Status and Its Impact on the Prognosis of Left-Sided and Right-Sided Colon Cancer: A SEER Population-Based Study. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 8708–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Kruijssen, D.E.W.; Brouwer, N.P.M.; Van Der Kuil, A.J.S.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Elias, S.G.; Vink, G.R.; Punt, C.J.A.; De Wilt, J.H.W.; Koopman, M. Interaction between Primary Tumor Resection, Primary Tumor Location, and Survival in Synchronous Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. Cancer Clin. Trials 2021, 44, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Eng, C.; Nieman, L.Z.; Kapadia, A.S.; Du, X.L. Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence by Anatomic Site and Disease Stage in the United States from 1976 to 2005. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. Cancer Clin. Trials 2011, 34, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugen, N.; Van de Velde, C.J.H.; De Wilt, J.H.W.; Nagtegaal, I.D. Metastatic Pattern in Colorectal Cancer Is Strongly Influenced by Histological Subtype. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekenkamp, L.J.M.; Heesterbeek, K.J.; Koopman, M.; Tol, J.; Teerenstra, S.; Venderbosch, S.; Punt, C.J.A.; Nagtegaal, I.D. Mucinous Adenocarcinomas: Poor Prognosis in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, A.; Percy, C.; Jack, A.; Shanmugaratnam, K.; Sobin, L.; Parkin, D.M.; Whelan, S. International Classification of Disease for Oncology, ICD-O, 3rd ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio; RStudio Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dickman, P.W.; Coviello, E. Estimating and Modeling Relative Survival. Stata J. 2015, 15, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, Q.; Cai, S.; Peng, J. Prognostic Effect of Tumor Sidedness in Colorectal Cancer: A SEER-Based Analysis. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2019, 18, e104–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.; Ping, J.; Li, Y.; Adell, G.; Arbman, G.; Nodin, B.; Meng, W.J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.Y.; Wang, C.; et al. The Prognostic Factors and Multiple Biomarkers in Young Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connell, J.B.; Maggard, M.A.; Livingston, E.H.; Yo, C.K. Colorectal Cancer in the Young. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 187, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, C.; Gerken, M.; Hirsch, D.; Fest, P.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Munker, S.; Schnoy, E.; Stroszczynski, C.; Vogelhuber, M.; Herr, W.; et al. Advanced Mucinous Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Prognosis and Efficacy of Chemotherapeutic Treatment. Digestion 2018, 98, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Hu, J.; Yang, D.; Cosgrove, D.P.; Xu, R. Pattern of Distant Metastases in Colorectal Cancer: A SEER Based Study. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38658–38666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Engstrand, J.; Nilsson, H.; Strömberg, C.; Jonas, E.; Freedman, J. Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases—A Population-Based Study on Incidence, Management and Survival. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brouwer, N.P.M.; van der Kruijssen, D.E.W.; Hugen, N.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Koopman, M.; de Wilt, J.H.W. The Impact of Primary Tumor Location in Synchronous Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Differences in Metastatic Sites and Survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Engbersen, M.P.; Nerad, E.; Rijsemus, C.J.V.; Buffart, T.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Aalbers, A.G.J.; Kok, N.F.M.; Lahaye, M.J. Differences in the Distribution of Peritoneal Metastases in Right- versus Left-Sided Colon Cancer on MRI. Abdom. Radiol. 2022, 47, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernly, S.; Wernly, B.; Semmler, G.; Bachmayer, S.; Niederseer, D.; Stickel, F.; Huber-Schönauer, U.; Aigner, E.; Datz, C. A Sex-Specific Propensity-Adjusted Analysis of Colonic Adenoma Detection Rates in a Screening Cohort. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 7508 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | <50 n (%) | 50–69 n (%) | >69 n (%) | p-Value |

| N | 297 (4.0) | 2627 (35.0) | 4584 (61.0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 146 (49.2) | 1579 (60.1) | 2357 (51.4) | <0.001 |

| Female | 151 (50.8) | 1048 (39.9) | 2227 (48.6) | |

| Site | ||||

| Left colon | 178 (59.9) | 1566 (59.6) | 2122 (46.3) | <0.001 |

| Right colon | 119 (40.1) | 1061 (40.4) | 2462 (53.7) | |

| Metastasis | ||||

| No | 158 (53.2) | 1559 (59.3) | 2724 (59.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 82 (27.6) | 446 (17.0) | 716 (15.6) | |

| Unknown | 57 (19.2) | 622 (23.7) | 1144 (25.0) | |

| Morphology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 248 (83.5) | 2334 (88.8) | 3997 (87.2) | 0.011 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 49 (16.5) | 293 (11.2) | 587 (12.8) | |

| MALE | FEMALE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | <50 n (%) | 50–69 n (%) | >69 n (%) | p-Value | <50 n (%) | 50–69 n (%) | >69 n (%) | p-Value |

| N | 146 (3.6) | 1579 (38.7) | 2357 (57.7) | 151 (4.4) | 1048 (30.6) | 2227 (65.0) | ||

| Site | ||||||||

| Left colon | 81 (55.5) | 985 (62.4) | 1241 (52.7) | <0.001 | 97 (64.2) | 581 (55.4) | 881 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Right colon | 65 (44.5) | 594 (37.6) | 1116 (47.3) | 54 (35.8) | 467 (44.6) | 1346 (60.4) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 75 (51.4) | 941 (59.6) | 1404 (59.6) | <0.001 | 83 (54.9) | 618 (59.0) | 1320 (59.3) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 44 (30.1) | 257 (16.3) | 364 (15.4) | 38 (25.2) | 189 (18.0) | 352 (15.8) | ||

| Unknown | 27 (18.5) | 381 (24.1) | 589 (25.0) | 30 (19.9) | 241 (23.0) | 555 (24.9) | ||

| Morphology | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 114 (78.1) | 1408 (89.2) | 2103 (89.2) | <0.001 | 134 (88.7) | 926 (88.4) | 1894 (85.0) | 0.02 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 32 (21.9) | 171 (10.8) | 254 (10.8) | 17 (11.3) | 122 (11.6) | 333 (15.0) | ||

| Age (Years) | <50 | 50–69 | >69 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | p-Value | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | p-Value | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | p-Value | |

| N | 146 (49.2) | 151 (50.8) | 0.8 | 1579 (60.1) | 1048 (39.9) | <0.001 | 2357 (51.4) | 2227 (48.6) | 0.05 |

| Site | |||||||||

| Left colon | 81 (55.5) | 97 (64.2) | 0.12 | 985 (62.4) | 581 (55.4) | <0.001 | 1241 (52.7) | 881 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Right colon | 65 (44.5) | 54 (35.8) | 594 (37.6) | 467 (44.6) | 1116 (47.3) | 1346 (60.4) | |||

| Metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 75 (51.4) | 83 (54.9) | 0.63 | 941 (59.6) | 618 (59.0) | 0.47 | 1404 (59.6) | 1320 (59.3) | 0.94 |

| Yes | 44 (30.1) | 38 (25.2) | 257 (16.3) | 189 (18.0) | 364 (15.4) | 352 (15.8) | |||

| Unknown | 27 (18.5) | 30 (19.9) | 381 (24.1) | 241 (23.0) | 589 (25.0) | 555 (24.9) | |||

| Morphology | |||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 114 (78.1) | 134 (88.7) | 0.01 | 1408 (89.2) | 926 (88.4) | 0.52 | 2103 (89.2) | 1894 (85.0) | <0.001 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 32 (21.9) | 17 (11.3) | 171 (10.8) | 122 (11.6) | 254 (10.8) | 333 (15.0) | |||

| N = 2038 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | <50 n (%) | 50–69 n (%) | >69 n (%) | p-Value |

| N | 130 (6.4) | 717 (35.2) | 1191 (58.4) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 72 (55.4) | 415 (57.9) | 605 (50.8) | 0.01 |

| Female | 58 (44.6) | 302 (42.1) | 586 (49.2) | |

| Site | ||||

| Left colon | 54 (41.5) | 277 (38.6) | 409 (34.3) | <0.001 |

| Right colon | 34 (26.2) | 201 (28.1) | 437 (36.7) | |

| Rectum | 26 (20.0) | 168 (23.4) | 205 (17.2) | |

| NOS | 16 (12.3) | 71 (9.9) | 140 (11.8) | |

| Morphology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 94 (72.3) | 560 (78.1) | 842 (70.7) | <0.001 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 25 (19.2) | 86 (12.0) | 122 (10.2) | |

| Other | 3 (2.3) | 16 (2.2) | 15 (1.3) | |

| NOS | 8 (6.2) | 55 (7.7) | 212 (17.8) | |

| N = 1511 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | <50 n (%) | 50–69 n (%) | >69 n (%) | p-Value |

| N | 103 (6.8) | 554 (36.7) | 854 (56.5) | |

| Liver * | ||||

| Yes | 64 (62.1) | 394 (71.1) | 538 (63.0) | 0.005 |

| No | 39 (37.9) | 160 (28.9) | 316 (37.0) | |

| Peritoneum * | ||||

| Yes | 26 (25.2) | 112 (20.2) | 193 (22.6) | 0.40 |

| No | 77 (74.8) | 442 (79.8) | 661 (77.4) | |

| Lung * | ||||

| Yes | 10 (9.7) | 60 (10.8) | 130 (15.2) | 0.03 |

| No | 93 (90.3) | 494 (89.2) | 724 (84.8) | |

| 0.65 | ||||

| Multiple sites | ||||

| Yes | 21 (20.4) | 95 (17.1) | 143 (16.7) | |

| No | 82 (79.6) | 459 (82.9) | 711 (83.3) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perotti, V.; Fabiano, S.; Contiero, P.; Michiara, M.; Musolino, A.; Boschetti, L.; Cascone, G.; Castelli, M.; Tagliabue, G.; Cancer Registries Working Group. Influence of Sex and Age on Site of Onset, Morphology, and Site of Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study on Data from Four Italian Cancer Registries. Cancers 2023, 15, 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030803

Perotti V, Fabiano S, Contiero P, Michiara M, Musolino A, Boschetti L, Cascone G, Castelli M, Tagliabue G, Cancer Registries Working Group. Influence of Sex and Age on Site of Onset, Morphology, and Site of Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study on Data from Four Italian Cancer Registries. Cancers. 2023; 15(3):803. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030803

Chicago/Turabian StylePerotti, Viviana, Sabrina Fabiano, Paolo Contiero, Maria Michiara, Antonio Musolino, Lorenza Boschetti, Giuseppe Cascone, Maurizio Castelli, Giovanna Tagliabue, and Cancer Registries Working Group. 2023. "Influence of Sex and Age on Site of Onset, Morphology, and Site of Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study on Data from Four Italian Cancer Registries" Cancers 15, no. 3: 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030803