Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bone Metastases in Prostate Cancer

3. Biology of Bone Metastases in Prostate Cancer

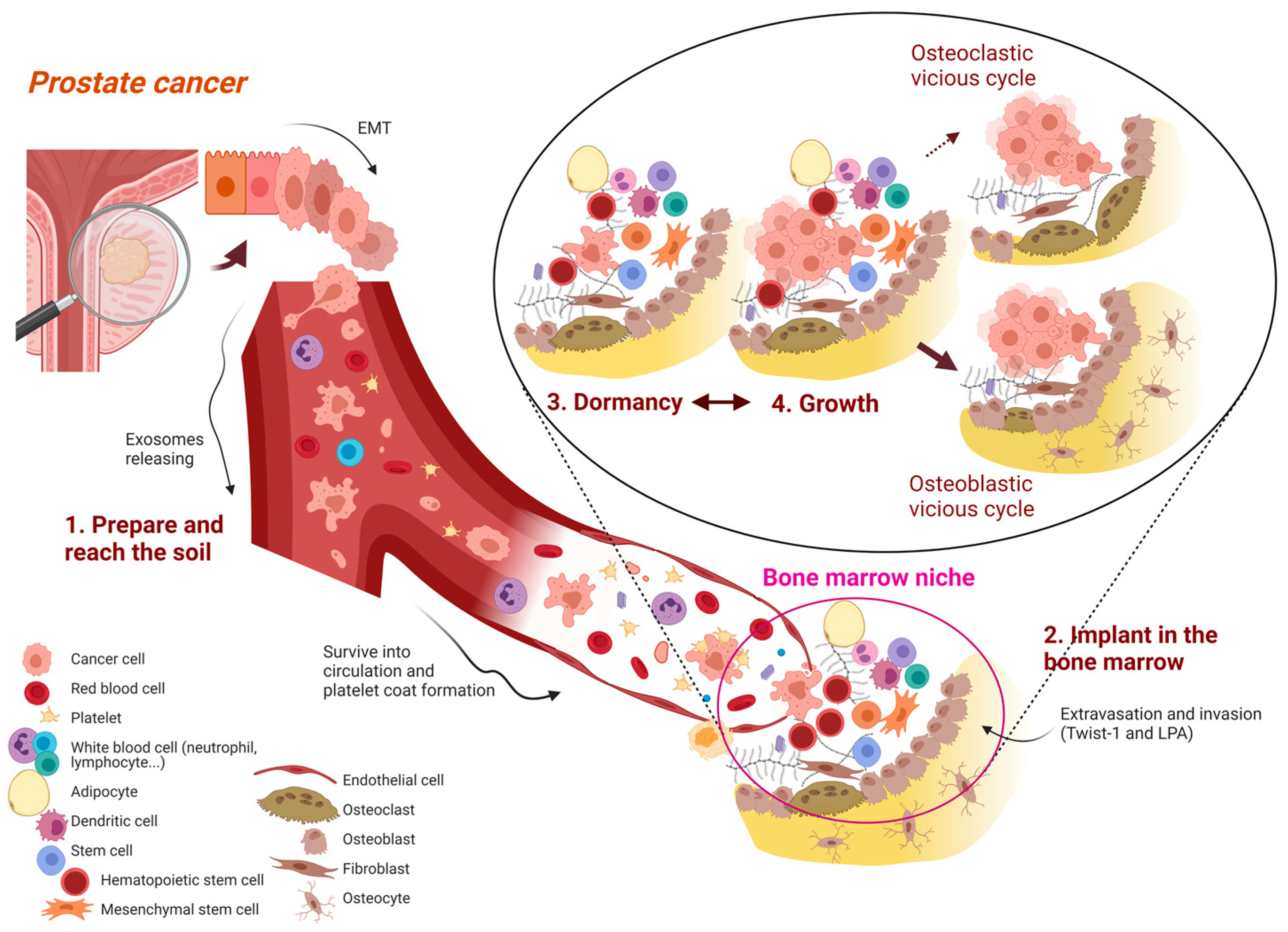

3.1. Prepare and Reach the Soil: The First, General Mechanisms

- A.

- Escape from primary tumor and prepare the metastatic niche

- B–C.

- Invasion of surrounding tissue and intravasation

- D–E.

- Survival in circulation and “attraction” to new locations

3.2. Implant in the Soil: Prostate Cancer Cell Homing in the Bone Marrow

- F.

- Arrest

- G.

- Extravasation

- H.

- Settlement

3.3. Dormancy: The Prelude of Detectable Bone Metastases

3.4. Growth: The “Clinical Phase” of Bone Metastasis

3.4.1. Osteolytic Lesions: The ‘Osteoclastic Vicious Cycle’

3.4.2. Sclerotic Lesions: The “Osteoblast Vicious Cycle”

3.4.3. Mixed Lesions

4. Molecular Subtypes of Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases: Beyond “Classical” Characteristics of Bone Metastases

5. Systemic Treatments in Prostate Cancer and Skeletal Related Events

6. Bone Health in Prostate Cancer

6.1. Bone Loss

6.2. Fracture Risk

6.3. Treatment for Bone Health in PC Patients

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SRE Skeletal-related event | |

| OS | overall survival |

| NTX | N-telopeptide of type I collagen |

| EMT | epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| ADT | androgen deprivation therapy |

| AME | The Italian Association of Clinical Endocrinologists |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| AR-Vs | androgen receptor variants |

| BALP | bone alkaline phosphatase |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BMP7 | bone morphogenetic protein |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| c-Myc | Cellular-myelocytomatosis viral oncogene |

| CRPC | castration resistant PC |

| CTC | circulating tumor cell |

| CTIBL | cancer treatment-induced bone loss |

| DC | dentritic cell |

| DKK | Dickkopf |

| DXA | dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry |

| EAA | The European Academy of Andrology |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EMT | epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| GAS | growth arrest-specific |

| GWAS | genome-wide expression |

| IBSP | integrin-binding sialoprotein |

| IGF-IR | IGF type I receptor |

| iMCs | immature myeloid cells |

| INFγ | interferon γ |

| LHRH | Hormone-releasing hormone |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| LPA | lysophosphatidic acid |

| Lu | Lutetium |

| mCRPC | metastatic CRPC |

| MDSC | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MPP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| NTX | N-telopeptide of type I collagen |

| ONJ | osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

| PC Prostate cancer | |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PSMA | prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| PTHrP | parathyroid hormone-related protein |

| QoL | quality of life |

| RLT | radioligant therapy |

| RR | relative risk |

| RT | radiotherapy |

| SCC | spinal cord compression |

| SERM | selective estrogen receptor modulators |

| SRE Skeletal-related event | |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TAN | neutrophil |

| TGF-β2 | transforming growth factor beta |

| VEGFR-1 | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 |

References

- Parker, C.; Castro, E.; Fizazi, K.; Heidenreich, A.; Ost, P.; Procopio, G.; Tombal, B.; Gillessen, S. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNatale, A.; Fatatis, A. The Bone Microenvironment in Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1210, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.; Hadji, P.; Body, J.-J.; Santini, D.; Chow, E.; Terpos, E.; Oudard, S.; Bruland, Ø.; Flamen, P.; Kurth, A.; et al. Bone health in cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1650–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.; Flamini, E.; Mercatali, L.; Sacanna, E.; Serra, P.; Amadori, D. Pathogenesis of osteoblastic bone metastases from prostate cancer. Cancer 2010, 116, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubendorf, L.; Schöpfer, A.; Wagner, U.; Sauter, G.; Moch, H.; Willi, N.; Gasser, T.C.; Mihatsch, M.J. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: An autopsy study of 1589 patients. Hum. Pathol. 2000, 31, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, L.A.; Fournier, P.G.J.; Chirgwin, J.M.; Guise, T.A. Molecular Biology of Bone Metastasis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Drzymalski, D.M.; Oh, W.; Werner, L.; Regan, M.M.; Kantoff, P.; Tuli, S. Predictors of survival in patients with prostate cancer and spinal metastasis: Presented at the 2009 Joint Spine Section Meeting. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2010, 13, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatini, P.; Larson, S.M.; Kremer, A.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Sun, M.; Yeung, H.; Imbriaco, M.; Horak, I.; Conolly, M.; Ding, C.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Extent of Disease in Bone in Patients With Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, C.J.; Lin, S.-H. Osteoblasts in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeneman, K.S.; Yeung, F.; Chung, L.W. Osteomimetic properties of prostate cancer cells: A hypothesis supporting the predilection of prostate cancer metastasis and growth in the bone environment. Prostate 1999, 39, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.-L.; Tarnowski, C.P.; Zhang, J.; Dai, J.; Rohn, E.; Patel, A.H.; Morris, M.D.; Keller, E.T. Bone metastatic LNCaP-derivative C4-2B prostate cancer cell line mineralizes in vitro. Prostate 2001, 47, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Mohler, J.L.; Ip, C. The transcriptomics of de novo androgen biosynthesis in prostate cancer cells following androgen reduction. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, J.; Xu, Q. Differences of osteoblastic bone metastases and osteolytic bone metastases in clinical features and molecular characteristics. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 17, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlüter, K.-D.; Katzer, C.; Piper, H.M. A N-terminal PTHrP peptide fragment void of a PTH/PTHrP-receptor binding domain activates cardiac ETA receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 132, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coleman, R.E.; Major, P.; Lipton, A.; Brown, J.E.; Lee, K.-A.; Smith, M.; Saad, F.; Zheng, M.; Hei, Y.J.; Seaman, J.; et al. Predictive Value of Bone Resorption and Formation Markers in Cancer Patients With Bone Metastases Receiving the Bisphosphonate Zoledronic Acid. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4925–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.; Lipton, A. Bone-marker levels in patients with prostate cancer: Potential correlations with outcomes. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2010, 4, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Feng, N.; Ning, C.; Wang, L.; Xue, L.; Zhang, Z. Serum ProGRP as a novel biomarker of bone metastasis in prostate cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 510, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aufderklamm, S.; Hennenlotter, J.; Rausch, S.; Bock, C.; Erne, E.; Schwentner, C.; Stenzl, A. Oncological validation of bone turnover markers c-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (1CTP) and peptides n-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (P1NP) in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 4000–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windrichová, J.; Kucera, R.; Fuchsova, R.; Topolcan, O.; Fiala, O.; Svobodova, J.; Finek, J.; Slipkova, D. An Assessment of Novel Biomarkers in Bone Metastatic Disease Using Multiplex Measurement and Multivariate Analysis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17, 1533033818807466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ku, X.; Cai, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yan, W. Data independent acquisition-mass spectrometry (DIA-MS)-based comprehensive profiling of bone metastatic cancers revealed molecular fingerprints to assist clinical classifications for bone metastasis of unknown primary (BMUP). Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 2390–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewing, J. A Treatise on Tumors; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer, C.L.; Weinberg, R.A. A Perspective on Cancer Cell Metastasis. Science 2011, 331, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massagué, J.; Obenauf, A.C. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature 2016, 529, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weidle, U.H.; Birzele, F.; Kollmorgen, G.; Rüger, R. The Multiple Roles of Exosomes in Metastasis. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2017, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Psaila, B.; Lyden, D. The metastatic niche: Adapting the foreign soil. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.N.; Riba, R.D.; Zacharoulis, S.; Bramley, A.H.; Vincent, L.; Costa, C.; MacDonald, D.D.; Jin, D.K.; Shido, K.; Kerns, S.A.; et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 2005, 438, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiratsuka, S.; Watanabe, A.; Aburatani, H.; Maru, Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nature 2006, 8, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erler, J.T.; Bennewith, K.L.; Cox, T.R.; Lang, G.; Bird, D.; Koong, A.; Le, Q.-T.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia-Induced Lysyl Oxidase Is a Critical Mediator of Bone Marrow Cell Recruitment to Form the Premetastatic Niche. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Littlepage, L.E.; Sternlicht, M.D.; Rougier, N.; Phillips, J.; Gallo, E.; Yu, Y.; Williams, K.; Brenot, A.; Gordon, J.I.; Werb, Z. Matrix Metalloproteinases Contribute Distinct Roles in Neuroendocrine Prostate Carcinogenesis, Metastasis, and Angiogenesis Progression. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2224–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, K.; Wu, Y.I.; Liu, Y.; Geiger, J.; Tam, E.; Overall, C.; Stack, M.S.; Friedl, P. Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nature 2007, 9, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckoff, J.; Wang, W.; Lin, E.Y.; Wang, Y.; Pixley, F.; Stanley, E.R.; Graf, T.; Pollard, J.W.; Segall, J.; Condeelis, J. A Paracrine Loop between Tumor Cells and Macrophages Is Required for Tumor Cell Migration in Mammary Tumors. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7022–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, E.Y.; Li, J.-F.; Gnatovskiy, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Grzesik, D.A.; Qian, H.; Xue, X.-N.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophages Regulate the Angiogenic Switch in a Mouse Model of Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11238–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harney, A.S.; Arwert, E.N.; Entenberg, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P.; Qian, B.-Z.; Oktay, M.H.; Pollard, J.W.; Jones, J.G.; Condeelis, J.S. Real-Time Imaging Reveals Local, Transient Vascular Permeability, and Tumor Cell Intravasation Stimulated by TIE2hi Macrophage–Derived VEGFA. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mazzone, M.; Dettori, D.; de Oliveira, R.L.; Loges, S.; Schmidt, T.; Jonckx, B.; Tian, Y.-M.; Lanahan, A.A.; Pollard, P.; de Almodovar, C.R.; et al. Heterozygous Deficiency of PHD2 Restores Tumor Oxygenation and Inhibits Metastasis via Endothelial Normalization. Cell 2009, 136, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gligorijevic, B.; Wyckoff, J.; Yamaguchi, H.; Wang, Y.; Roussos, E.T.; Condeelis, J. N-WASP-mediated invadopodium formation is involved in intravasation and lung metastasis of mammary tumors. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Langenkamp, E.; Georganaki, M.; Loskog, A.; Fuchs, P.F.; Dieterich, L.C.; Kreuger, J.; Dimberg, A. VEGF suppresses T-lymphocyte infiltration in the tumor microenvironment through inhibition of NF-κB-induced endothelial activation. FASEB J. 2014, 29, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buckanovich, R.J.; Facciabene, A.; Kim, S.; Benencia, F.; Sasaroli, D.; Balint, K.; Katsaros, D.; O’Brien-Jenkins, A.; Gimotty, P.A.; Coukos, G. Endothelin B receptor mediates the endothelial barrier to T cell homing to tumors and disables immune therapy. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motz, G.T.; Santoro, S.P.; Wang, L.-P.; Garrabrant, T.; Lastra, R.R.; Hagemann, I.S.; Lal, P.; Feldman, M.D.; Benencia, F.; Coukos, G. Tumor endothelium FasL establishes a selective immune barrier promoting tolerance in tumors. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micalizzi, D.; Maheswaran, S.; Haber, D.A. A conduit to metastasis: Circulating tumor cell biology. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1827–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieswandt, B.; Hafner, M.; Echtenacher, B.; Männel, D.N. Lysis of tumor cells by natural killer cells in mice is impeded by platelets. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Mok, S.C.; Xue, F.; Zhang, W. CXCL12/CXCR4: A symbiotic bridge linking cancer cells and their stromal neighbors in oncogenic communication networks. Oncogene 2015, 35, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfar, G.A.; Ebrahim, M.A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Eissa, L.A. Validity of Osteoprotegerin and Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand for the Detection of Bone Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2017, 25, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.J.; Mousa, S.A. Anti-cancer properties of low-molecular-weight heparin: Preclinical evidence. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 102, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Läubli, H.; Borsig, L. Selectins promote tumor metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2010, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiratsuka, S.; Goel, S.; Kamoun, W.S.; Maru, Y.; Fukumura, D.; Duda, D.G.; Jain, R.K. Endothelial focal adhesion kinase mediates cancer cell homing to discrete regions of the lungs via E-selectin up-regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3725–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boucharaba, A.; Serre, C.-M.; Grès, S.; Saulnier-Blache, J.S.; Bordet, J.-C.; Guglielmi, J.; Clézardin, P.; Peyruchaud, O. Platelet-derived lysophosphatidic acid supports the progression of osteolytic bone metastases in breast cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reymond, N.; D’Agua, B.B.; Ridley, A.J. Crossing the endothelial barrier during metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.R.; McLean, L.; Walsh, M.; Taylor, J.; Hayasaka, S.; Bhatia, J.; Pienta, K. Preferential adhesion of prostate cancer cells to bone is mediated by binding to bone marrow endothelial cells as compared to extracellular matrix components in vitro. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 4839–4847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Shiozawa, Y.; Wang, J.; McGregor, N.; Dai, J.; Park, S.I.; Berry, J.E.; Havens, A.M.; Joseph, J.; Kim, J.K.; et al. Prevalence of Prostate Cancer Metastases after Intravenous Inoculation Provides Clues into the Molecular Basis of Dormancy in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. Neoplasia 2012, 14, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Drabsch, Y.; Dijke, P.T. TGF-β Signaling in Breast Cancer Cell Invasion and Bone Metastasis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2011, 16, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chinni, S.R.; Sivalogan, S.; Dong, Z.; Filho, J.C.T.; Deng, X.; Bonfil, R.D.; Cher, M.L. CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling activates Akt-1 and MMP-9 expression in prostate cancer cells: The role of bone microenvironment-associated CXCL12. Prostate 2005, 66, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, W.; Nor, J.E.; Wang, C.Y.; Taichman, R.S. RETRACTED: Diverse signaling pathways through the SDF-1/CXCR4 chemokine axis in prostate cancer cell lines leads to altered patterns of cytokine secretion and angiogenesis. Cell. Signal. 2005, 17, 1578–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engl, T.; Relja, B.; Marian, D.; Blumenberg, C.; Müller, I.; Beecken, W.-D.; Jones, J.; Ringel, E.M.; Bereiter-Hahn, J.; Jonas, D.; et al. CXCR4 Chemokine Receptor Mediates Prostate Tumor Cell Adhesion through α5 and β3 Integrins. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCabe, N.P.; De, S.; Vasanji, A.; Brainard, J.; Byzova, T.V. Prostate cancer specific integrin αvβ3 modulates bone metastatic growth and tissue remodeling. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6238–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.L.; Dai, J.; van Golen, K.L.; Keller, E.T.; Long, M.W. Type I Collagen Receptor (α2β1) Signaling Promotes the Growth of Human Prostate Cancer Cells within the Bone. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8648–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sottnik, J.L.; Daignault-Newton, S.; Zhang, X.; Morrissey, C.; Hussain, M.H.; Keller, E.T.; Hall, C.L. Integrin alpha2beta1 (α2β1) promotes prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2012, 30, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glinsky, V.; Glinsky, G.V.; Rittenhouse-Olson, K.; Huflejt, M.; Glinskii, O.V.; Deutscher, S.L.; Quinn, T.P. The role of Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen in adhesion of human breast and prostate cancer cells to the endothelium. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4851–4857. [Google Scholar]

- Urata, S.; Izumi, K.; Hiratsuka, K.; Maolake, A.; Natsagdorj, A.; Shigehara, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Kadomoto, S.; Makino, T.; Naito, R.; et al. C-C motif ligand 5 promotes migration of prostate cancer cells in the prostate cancer bone metastasis microenvironment. Cancer Sci. 2017, 109, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiozawa, Y.; Havens, A.M.; Jung, Y.; Ziegler, A.M.; Pedersen, E.A.; Wang, J.; Lu, G.; Roodman, G.D.; Loberg, R.D.; Pienta, K.J.; et al. Annexin II/Annexin II receptor axis regulates adhesion, migration, homing, and growth of prostate cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Yu, C.; Gao, X.; Welte, T.; Muscarella, A.M.; Tian, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Z.; Du, S.; Tao, J.; et al. The Osteogenic Niche Promotes Early-Stage Bone Colonization of Disseminated Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michigami, T.; Shimizu, N.; Williams, P.J.; Niewolna, M.; Dallas, S.L.; Mundy, G.R.; Yoneda, T. Cell-cell contact between marrow stromal cells and myeloma cells via VCAM-1 and alpha(4)beta(1)-integrin enhances production of osteoclast-stimulating activity. Blood 2000, 96, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croset, M.; Goehrig, D.; Frackowiak, A.; Bonnelye, E.; Ansieau, S.; Puisieux, A.; Clézardin, P. TWIST1 Expression in Breast Cancer Cells Facilitates Bone Metastasis Formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1886–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, D.; Leblanc, R.; Grunewald, T.G.P.; Ambatipudi, S.; Ribeiro, J.; Clézardin, P.; Peyruchaud, O. The LPA1/ZEB1/miR-21-activation pathway regulates metastasis in basal breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 20604–20620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luzzi, K.J.; Macdonald, I.C.; Schmidt, E.E.; Kerkvliet, N.; Morris, V.L.; Chambers, A.F.; Groom, A.C. Multistep Nature of Metastatic Inefficiency: Dormancy of solitary cells after successful extravasation and limited survival of early micrometastases. Am. J. Pathol. 1998, 153, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozawa, Y.; Pedersen, E.A.; Patel, L.R.; Ziegler, A.M.; Havens, A.M.; Jung, Y.; Wang, J.; Zalucha, S.; Loberg, R.D.; Pienta, K.J.; et al. GAS6/AXL Axis Regulates Prostate Cancer Invasion, Proliferation, and Survival in the Bone Marrow Niche. Neoplasia 2010, 12, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sosa, M.S.; Bragado, P.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: An awakening field. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, A.; Gupta, P.B.; Sgroi, D.C.; Arenzana-Seisdedos, F.; Delaunay, T.; Naeem, R.; Carey, V.J.; Richardson, A.L.; Weinberg, R.A. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell 2005, 121, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Lambert, D.W. Cancer-associated fibroblasts—Not-so-innocent bystanders in metastasis to bone? J. Bone Oncol. 2016, 5, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Bhatia, R. Stem Cell Quiescence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 4936–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Owen, K.L.; Parker, B.S. Beyond the vicious cycle: The role of innate osteoimmunity, automimicry and tumor-inherent changes in dictating bone metastasis. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 110, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghajar, C.M.; Peinado, H.; Mori, H.; Matei, I.R.; Evason, K.J.; Brazier, H.; Almeida, D.; Koller, A.; Hajjar, K.A.; Stainier, D.Y.; et al. The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herroon, M.K.; Rajagurubandara, E.; Hardaway, A.L.; Powell, K.; Turchick, A.; Feldmann, D.; Podgorski, I. Bone marrow adipocytes promote tumor growth in bone via FABP4-dependent mechanisms. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 2108–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herroon, M.K.; Rajagurubandara, E.; Rudy, D.L.; Chalasani, A.; Hardaway, A.L.; Podgorski, I. Macrophage cathepsin K promotes prostate tumor progression in bone. Oncogene 2012, 32, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barkan, D.; El Touny, L.H.; Michalowski, A.M.; Smith, J.A.; Chu, I.; Davis, A.S.; Webster, J.D.; Hoover, S.; Simpson, R.M.; Gauldie, J.; et al. Metastatic Growth from Dormant Cells Induced by a Col-I–Enriched Fibrotic Environment. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5706–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Liu, D.; Mignatti, A.; Kovalski, K.; Ossowski, L. Urokinase Receptor and Fibronectin Regulate the ERKMAPK to p38MAPK Activity Ratios That Determine Carcinoma Cell Proliferation or Dormancy In Vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goedegebuure, P.; Mitchem, J.B.; Porembka, M.R.; Tan, M.C.; Belt, B.A.; WangGillam, A.E.; Gillanders, W.G.; Hawkins, W.C.; Linehan, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: General characteristics and relevance to clinical management of pancreatic cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targ. 2011, 11, 734–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sawant, A.; Hensel, J.A.; Chanda, D.; Harris, B.A.; Siegal, G.P.; Maheshwari, A.; Ponnazhagan, S. Depletion of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Inhibits Tumor Growth and Prevents Bone Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4258–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allaeys, I.; Rusu, D.; Picard, S.; Pouliot, M.; Borgeat, P.; Poubelle, P.E. Osteoblast retraction induced by adherent neutrophils promotes osteoclast bone resorption: Implication for altered bone remodeling in chronic gout. Lab. Investig. 2011, 91, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Gall, C.; Bellahcène, A.; Bonnelye, E.; Gasser, J.A.; Castronovo, V.; Green, J.; Zimmermann, J.; Clézardin, P. A Cathepsin K Inhibitor Reduces Breast Cancer–Induced Osteolysis and Skeletal Tumor Burden. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9894–9902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellahcène, A.; Bachelier, R.; Detry, C.; Lidereau, R.; Clézardin, P.; Castronovo, V. Transcriptome analysis reveals an osteoblast-like phenotype for human osteotropic breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006, 101, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelek, J.M.; Chakraborty, A.K. Fusion of tumour cells with bone marrow-derived cells: A unifying explanation for metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Mu, E.; Wei, Y.; Riethdorf, S.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, M.; Yan, J.; Hua, Y.; Tiede, B.J.; Lu, X.; et al. VCAM-1 Promotes Osteolytic Expansion of Indolent Bone Micrometastasis of Breast Cancer by Engaging α4β1-Positive Osteoclast Progenitors. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dayyani, F.; Parikh, N.; Song, J.H.; Araujo, J.C.; Carboni, J.M.; Gottardis, M.M.; Trudel, G.C.; Logothetis, C.; Gallick, G.E. Inhibition of Src and insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IR/IGF-1R) on tumors and bone turnover in prostate cancer (PCa) models in vivo compared with inhibition of either kinase alone. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P.G.; Juárez, P.; Jiang, G.; Clines, G.A.; Niewolna, M.; Kim, H.S.; Walton, H.W.; Peng, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Mohammad, K.S.; et al. The TGF-β Signaling Regulator PMEPA1 Suppresses Prostate Cancer Metastases to Bone. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, J.; Schneider, A.; Datta, N.S.; McCauley, L.K. Extracellular Calcium as a Candidate Mediator of Prostate Cancer Skeletal Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 9065–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whang, P.G.; Schwarz, E.M.; Gamradt, S.C.; Dougall, W.C.; Lieberman, J.R. The effects of RANK blockade and osteoclast depletion in a model of pure osteoblastic prostate cancer metastasis in bone. J. Orthop. Res. 2005, 23, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.M.; Lemos, J.M.; Alho, I.; Valério, D.; Ferreira, A.R.; Costa, L.; Vinga, S. Dynamic modeling of bone metastasis, microenvironment and therapy: Integrating parathyroid hormone (PTH) effect, anti-resorptive and anti-cancer therapy. J. Theor. Biol. 2016, 391, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.L.; Kang, S.; MacDougald, O.; Keller, E.T. Role of wnts in prostate cancer bone metastases. J. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 97, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.L.; Daignault, S.D.; Shah, R.B.; Pienta, K.; Keller, E.T. Dickkopf-1 expression increases early in prostate cancer development and decreases during progression from primary tumor to metastasis. Prostate 2008, 68, 1396–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yavropoulou, M.P.; van Lierop, A.H.; Hamdy, N.A.; Rizzoli, R.; Papapoulos, S.E. Serum sclerostin levels in Paget’s disease and prostate cancer with bone metastases with a wide range of bone turnover. Bone 2012, 51, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, S.; Cao, S.; Jin, L.; Kobelski, M.; Schouest, B.; Wang, X.; Ungerleider, N.; Baddoo, M.; Zhang, W.; Corey, E.; et al. A positive role of c-Myc in regulating androgen receptor and its splice variants in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2019, 38, 4977–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Boufaied, N.; Hallal, T.; Feit, A.; de Polo, A.; Luoma, A.M.; Alahmadi, W.; Larocque, J.; Zadra, G.; Xie, Y.; et al. MYC drives aggressive prostate cancer by disrupting transcriptional pause release at androgen receptor targets. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weilbaecher, K.N.; Guise, T.A.; McCauley, L.K. Cancer to bone: A fatal attraction. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Augello, M.A.; Den, R.B.; Knudsen, K.E. AR function in promoting metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014, 33, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylitalo, E.B.; Thysell, E.; Jernberg, E.; Lundholm, M.; Crnalic, S.; Egevad, L.; Stattin, P.; Widmark, A.; Bergh, A.; Wikström, P. Subgroups of Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases Defined Through an Inverse Relationship Between Androgen Receptor Activity and Immune Response. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thysell, E.; Vidman, L.; Ylitalo, E.B.; Jernberg, E.; Crnalic, S.; Iglesias-Gato, D.; Flores-Morales, A.; Stattin, P.; Egevad, L.; Widmark, A.; et al. Gene expression profiles define molecular subtypes of prostate cancer bone metastases with different outcomes and morphology traceable back to the primary tumor. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 1763–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thysell, E.; Köhn, L.; Semenas, J.; Järemo, H.; Freyhult, E.; Lundholm, M.; Karlsson, C.T.; Damber, J.; Widmark, A.; Crnalic, S.; et al. Clinical and biological relevance of the transcriptomic-based prostate cancer metastasis subtypes MetA-C. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 16, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, P.; Bergström, S.H.; Josefsson, A.; Semenas, J.; Nordstrand, A.; Thysell, E.; Crnalic, S.; Widmark, A.; Karlsson, C.T.; Bergh, A. Epithelial and Stromal Characteristics of Primary Tumors Predict the Bone Metastatic Subtype of Prostate Cancer and Patient Survival after Androgen-Deprivation Therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, J.L.; Antonarakis, E.S. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Management of Prostate Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 583–586. [Google Scholar]

- Shahinian, V.B.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Freeman, J.L.; Goodwin, J.S. Risk of Fracture after Androgen Deprivation for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rozet, F.; Hennequin, C.; Beauval, J.-B.; Beuzeboc, P.; Cormier, L.; Fromont, G.; Mongiat-Artus, P.; Ouzzane, A.; Ploussard, G.; Azria, D.; et al. Recommandations en onco-urologie 2016–2018 du CCAFU: Cancer de la prostate. Progrès Urol. 2016, 27, S95–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson, M.D.; Marujo, R.M.; Smith, M.R. Contribution of Androgen Deprivation Therapy to Elevated Osteoclast Activity in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 2705–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.R.; McGovern, F.J.; Zietman, A.L.; Fallon, M.A.; Hayden, D.L.; Schoenfeld, D.A.; Kantoff, P.W.; Finkelstein, J.S. Pamidronate to Prevent Bone Loss during Androgen-Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Lee, W.C.; Brandman, J.; Wang, Q.; Botteman, M.; Pashos, C.L. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists and Fracture Risk: A Claims-Based Cohort Study of Men With Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7897–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higano, C.S. Androgen-deprivation-therapy-induced fractures in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer: What do we really know? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2008, 5, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bono, J.S.; Logothetis, C.J.; Molina, A.; Fizazi, K.; North, S.; Chu, L.; Chi, K.N.; Jones, R.J.; Goodman, O.B., Jr.; Saad, F.; et al. Abiraterone and Increased Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.M.; Armstrong, A.J.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Loriot, Y.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carles, J.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. Enzalutamide in Metastatic Prostate Cancer before Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.R.; Saad, F.; Chowdhury, S.; Oudard, S.; Hadaschik, B.A.; Graff, J.N.; Olmos, D.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Lee, J.Y.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide Treatment and Metastasis-free Survival in Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Shore, N.; Tammela, T.L.; Ulys, A.; Vjaters, E.; Polyakov, S.; Jievaltas, M.; Luz, M.; Alekseev, B.; Kuss, I.; et al. Darolutamide in Nonmetastatic, Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannock, I.F.; De Wit, R.; Berry, W.R.; Horti, J.; Pluzanska, A.; Chi, K.N.; Oudard, S.; Théodore, C.; James, N.D.; Turesson, I.; et al. Docetaxel plus Prednisone or Mitoxantrone plus Prednisone for Advanced Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Bono, J.S.; Oudard, S.; Ozguroglu, M.; Hansen, S.; Machiels, J.-P.; Kocak, I.; Gravis, G.; Bodrogi, I.; Mackenzie, M.J.; Shen, L.; et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Høiberg, M.; Nielsen, T.L.; Wraae, K.; Abrahamsen, B.; Hagen, C.; Andersen, M.; Brixen, K. Population-based reference values for bone mineral density in young men. Osteoporos. Int. 2007, 18, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, L.J.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Cooper, C.; Lane, A.W.; Riggs, B.L. How Many Women Have Osteoporosis? J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005, 20, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, C.J.; Basch, E.; Molina, A.; Fizazi, K.; North, S.A.; Chi, K.N.; Jones, R.J.; Goodman, O.B.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Sternberg, C.N.; et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate and prednisone compared with placebo and prednisone on pain control and skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Exploratory analysis of data from the COU-AA-301 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.J.; Smith, M.R.; De Bono, J.S.; Molina, A.; Logothetis, C.J.; De Souza, P.; Fizazi, K.; Mainwaring, P.; Piulats, J.M.; Ng, S.; et al. Abiraterone in Metastatic Prostate Cancer without Previous Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, N.D.; De Bono, J.S.; Spears, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Ritchie, A.W.S.; Amos, C.L.; Gilson, C.; Jones, R.J.; et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.-E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; De Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. Increased Survival with Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer after Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, M.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Rathenborg, P.; Shore, N.; Ferreira, U.; Ivashchenko, P.; Demirhan, E.; Modelska, K.; Phung, D.; et al. Enzalutamide in Men with Nonmetastatic, Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2465–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenzl, A.; Hegemann, M.; Maas, M.; Rausch, S.; Walz, S.; Bedke, J.; Todenhöfer, T. Current concepts and trends in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 2019, 21, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.; Fossa, S.; Chodacki, A.; Wedel, S.; Bruland, O.; Staudacher, K.; Garcia-Vargas, J.; Sartor, O. Time to first skeletal-related event (SRE) with radium-223 dichloride (Ra-223) in patients with castration- resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and bone metastases: ALSYMPCA trial stratification factors analysis. In Proceedings of the European Cancer Congress 2013, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27 September–1 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Parker, C.; Saad, F.; Miller, K.; Tombal, B.; Ng, Q.S.; Boegemann, M.; Matveev, V.; Piulats, J.M.; Zucca, L.E.; et al. Addition of radium-223 to abiraterone acetate and prednisone or prednisolone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases (ERA 223): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, O.; de Bono, J.; Chi, K.N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nordquist, L.T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G.; et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerecker, B.; Tauber, R.; Knorr, K.; Heck, M.; Beheshti, A.; Seidl, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Pickhard, A.; Gafita, A.; Kratochwil, C.; et al. Activity and Adverse Events of Actinium-225-PSMA-617 in Advanced Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer After Failure of Lutetium-177-PSMA. Eur. Urol. 2020, 79, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Gomes, A.J.P.D.S.; Given, R.; Soto, A.J.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroglu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Azad, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Iguchi, T.; Shore, N.D.; et al. ARCHES: A Randomized, Phase III Study of Androgen Deprivation Therapy With Enzalutamide or Placebo in Men With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.-N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; Sydes, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Spears, M.R.; Ritchie, A.W.S.; Parker, C.C.; Russell, J.M.; Attard, G.; et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): Survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lassemillante, A.-C.M.; Doi, S.; Hooper, J.; Prins, J.; Wright, O. Prevalence of osteoporosis in prostate cancer survivors II: A meta-analysis of men not on androgen deprivation therapy. Endocrine 2015, 50, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, J.; Morin, J.P.; Orsola, A.; Abascal, J.M.; Salvador, C.; Trilla, E.; Raventos, C.X.; Cecchini, L.; Encabo, G.; Reventos, J. Prevalence of Osteoporosis During Long-Term Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Patients with Prostate Cancer. Urology 2007, 69, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibhai, S.M.H.; Mohamedali, H.Z.; Gulamhusein, H.; Panju, A.H.; Breunis, H.; Timilshina, N.; Fleshner, N.; Krahn, M.; Naglie, G.; Tannock, I.F.; et al. Changes in bone mineral density in men starting androgen deprivation therapy and the protective role of vitamin D. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higano, C.; Shields, A.; Wood, N.; Brown, J.; Tangen, C. Bone mineral density in patients with prostate cancer without bone metastases treated with intermittent androgen suppression. Urology 2004, 64, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittan, D.; Lee, S.; Miller, E.; Perez, R.C.; Basler, J.W.; Bruder, J.M. Bone Loss following Hypogonadism in Men with Prostate Cancer Treated with GnRH Analogs. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 3656–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, D.M.; Torréns, J.I.; Harding, P.; Howard, R.S.; Duncan, W.E.; Mcleod, D.G. Androgen deprivation in men with prostate cancer is associated with an increased rate of bone loss. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002, 5, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daniell, H.W.; Dunn, S.R.; Ferguson, D.W.; Lomas, G.; Niazi, Z.; Stratte, P.T. Progressive osteoporosis during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2000, 163, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spry, N.A.; Galvão, D.A.; Davies, R.; La Bianca, S.; Joseph, D.; Davidson, A.; Prince, R. Long-term effects of intermittent androgen suppression on testosterone recovery and bone mineral density: Results of a 33-month observational study. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.Y.; Kuo, K.F.; Gulati, R.; Chen, S.; Gambol, T.E.; Hall, S.P.; Jiang, P.Y.; Pitzel, P.; Higano, C.S. Long-Term Dynamics of Bone Mineral Density During Intermittent Androgen Deprivation for Men With Nonmetastatic, Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conde, F.A.; Sarna, L.; Oka, R.K.; Vredevoe, D.L.; Rettig, M.B.; Aronson, W.J. Age, body mass index, and serum prostate-specific antigen correlate with bone loss in men with prostate cancer not receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Urology 2004, 64, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.-K.; Lee, E.; Prior, H.J.; Lix, L.M.; Metge, C.; Leslie, W.D. Fracture risk in androgen deprivation therapy: A Canadian population based analysis. Can. J. Urol. 2009, 16, 4908–4914. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlborg, H.G.; Nguyen, N.D.; Center, J.R.; Eisman, J.A.; Nguyen, T.V. Incidence and risk factors for low trauma fractures in men with prostate cancer. Bone 2008, 43, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibhai, S.M.; Duong-Hua, M.; Cheung, A.M.; Sutradhar, R.; Warde, P.; Fleshner, N.E.; Paszat, L. Fracture Types and Risk Factors in Men With Prostate Cancer on Androgen Deprivation Therapy: A Matched Cohort Study of 19,079 Men. J. Urol. 2010, 184, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saylor, P.J.; Morton, R.A.; Hancock, M.L.; Barnette, K.G.; Steiner, M.S.; Smith, M.R. Factors Associated With Vertebral Fractures in Men Treated With Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rana, K.; Lee, N.K.; Zajac, J.D.; MacLean, H.E. Expression of androgen receptor target genes in skeletal muscle. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.A.; Hastings, F.W.; Petkov, V.I. Treatment thresholds for osteoporosis in men on androgen deprivation therapy: T-score versus FRAX™. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 21, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescini, F.; Attanasio, R.; Balestrieri, A.; Bandeira, F.; Bonadonna, S.; Camozzi, V.; Cassibba, S.; Cesareo, R.; Chiodini, I.; Francucci, C.M.; et al. Italian association of clinical endocrinologists (AME) position statement: Drug therapy of osteoporosis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 807–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Tosteson, A.N.A.; Melton, L.J.; Baim, S.; Favus, M.J.; Khosla, S.; Lindsay, R.L. Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos. Int. 2008, 19, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berruti, A.; Tucci, M.; Mosca, A.; Tarabuzzi, R.; Gorzegno, G.; Terrone, C.; Vana, F.; Lamanna, G.; Tampellini, M.; Porpiglia, F.; et al. Predictive factors for skeletal complications in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients with metastatic bone disease. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Prostate Cancer (Version 2.2021). Available online: http://www.nccn.org/profes-sionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Rochira, V.; Antonio, L.; Vanderschueren, D. EAA clinical guideline on management of bone health in the andrological outpatient clinic. Andrology 2018, 6, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.S.; Tobiasmachado, M.; Esteves, M.A.P.; Senra, M.D.; Wroclawski, M.L.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Reis, R.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; Del Giglio, A. Bisphosphonate therapy in patients under androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011, 15, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenspan, S.L.; Nelson, J.B.; Trump, D.L.; Resnick, N.M. Effect of Once-Weekly Oral Alendronate on Bone Loss in Men Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, D.L.; Timms, E.; Tan, H.L.; Kelley, M.J.; Dunstan, C.R.; Burgess, T.; Elliott, R.; Colombero, A.; Elliott, G.; Scully, S.; et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 1998, 93, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langdahl, B.L.; Teglbjærg, C.S.; Ho, P.-R.; Chapurlat, R.; Czerwinski, E.; Kendler, D.L.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Kivitz, A.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Miller, P.D.; et al. A 24-Month Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Denosumab for the Treatment of Men With Low Bone Mineral Density: Results From the ADAMO Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.R.; Egerdie, B.; Toriz, N.H.; Feldman, R.; Tammela, T.L.; Saad, F.; Heracek, J.; Szwedowski, M.; Ke, C.; Kupic, A.; et al. Denosumab in Men Receiving Androgen-Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Joseph, J.S.; Lam, V.; Patel, M.I. Preventing Osteoporosis in Men Taking Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oronzo, S.; Coleman, R.; Brown, J.; Silvestris, F. Metastatic bone disease: Pathogenesis and therapeutic options: Up-date on bone metastasis management. J. Bone Oncol. 2019, 15, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, C.L.; Burdett, S.; Rydzewska, L.H.M.; Albiges, L.; Clarke, N.W.; Fisher, D.; Fizazi, K.; Gravis, G.; James, N.D.; Mason, M.D.; et al. Addition of docetaxel or bisphosphonates to standard of care in men with localised or metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analyses of aggregate data. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saad, F.; Gleason, D.M.; Murray, R.; Tchekmedyian, S.; Venner, P.; Lacombe, L.; Chin, J.L.; Vinholes, J.J.; Goas, J.A.; Zheng, M. Long-Term Efficacy of Zoledronic Acid for the Prevention of Skeletal Complications in Patients With Metastatic Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 96, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fizazi, K.; Carducci, M.; Smith, M.; Damião, R.; Brown, J.; Karsh, L.; Milecki, P.; Shore, N.; Rader, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: A randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2011, 377, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saad, F.; Brown, J.E.; Van Poznak, C.; Ibrahim, T.; Stemmer, S.M.; Stopeck, A.T.; Diel, I.J.; Takahashi, S.; Shore, N.; Henry, D.H.; et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: Integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 23, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.R.; Eastham, J.; Gleason, D.M.; Shasha, D.; Tchekmedyian, S.; Zinner, N. Randomized Controlled Trial of Zoledronic Acid to Prevent Bone Loss in Men Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israeli, R.S.; Rosenberg, S.J.; Saltzstein, D.R.; Gottesman, J.E.; Goldstein, H.R.; Hull, G.W.; Tran, D.N.; Warsi, G.M.; Lacerna, L.V. The Effect of Zoledronic Acid on Bone Mineral Density in Patients Undergoing Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2007, 5, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson, D.; Kaufman, D.S.; Lee, H.; McGovern, F.J.; Kantoff, P.; Fallon, M.A.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Smith, M.R. Randomized Controlled Trial of Annual Zoledronic Acid to Prevent Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist–Induced Bone Loss in Men With Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.W.; Huo, D.; Bylow, K.; Demers, L.M.; Stadler, W.M.; Henderson, T.O.; Vogelzang, N.J. Suppression of bone density loss and bone turnover in patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer and receiving zoledronic acid. BJU Int. 2007, 100, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, S.L.; Nelson, J.B.; Trump, D.L.; Wagner, J.M.; Miller, M.E.; Perera, S.; Resnick, N.M. Skeletal Health After Continuation, Withdrawal, or Delay of Alendronate in Men With Prostate Cancer Undergoing Androgen-Deprivation Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4426–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhoopalam, N.; Campbell, S.C.; Moritz, T.; Broderick, W.R.; Iyer, P.; Arcenas, A.G.; Van Veldhuizen, P.J.; Friedman, N.; Reda, D.; Warren, S.; et al. Intravenous Zoledronic Acid to Prevent Osteoporosis in a Veteran Population With Multiple Risk Factors for Bone Loss on Androgen Deprivation Therapy. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.M.; Wallace, M.; Becker, J.T.; Eickhoff, J.C.; Buehring, B.; Binkley, N.; Staab, M.J.; Wilding, G.; Liu, G.; Malkovsky, M.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Trial Evaluating Different Schedules of Zoledronic Acid on Bone Mineral Density in Patients With Prostate Cancer Beginning Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2013, 11, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, P.; Meler, A.; Hering, F. Titration of Dosage for the Protective Effect of Zoledronic Acid on Bone Loss in Patients Submitted to Androgen Deprivation Therapy due to Prostate Cancer: A Prospective Open-Label Study. Urol. Int. 2010, 85, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachnic, L.A.; Pugh, S.L.; Tai, P.; Smith, M.; Gore, E.; Shah, A.B.; Martin, A.-G.; Kim, H.E.; Nabid, A.; Lawton, C.A. RTOG 0518: Randomized phase III trial to evaluate zoledronic acid for prevention of osteoporosis and associated fractures in prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013, 16, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mjelstad, A.; Zakariasson, G.; Valachis, A. Optimizing antiresorptive treatment in patients with bone metastases: Time to initiation, switching strategies, and treatment duration. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3859–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Himelstein, A.L.; Foster, J.C.; Khatcheressian, J.L.; Roberts, J.D.; Seisler, D.K.; Novotny, P.J.; Qin, R.; Go, R.S.; Grubbs, S.S.; O’Connor, T.; et al. Effect of Longer-Interval vs Standard Dosing of Zoledronic Acid on Skeletal Events in Patients With Bone Metastases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, S.E.; Chow, R.; Raman, S.; Zeng, K.L.; Lutz, S.; Lam, H.; Silva, M.F.; Chow, E. Update of the systematic review of palliative radiation therapy fractionation for bone metastases. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Process | Cells Other than Cancer Cells | Molecules | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From Tumor | From Other Cells | ||||

| 1 | Prepare and Reach the Soil | ||||

| A | Escape from primary tumor and prepare metastatic niche | Fibroblasts; Hematopoietic stem cells | Exosomes with integrins; VEGF-A, TGF-β and TNF-α; MMP-9, LOX | Fibronectin VEGFR-1 | |

| B | Invasion of surrounding tissue | TAM | MMP-1,2,7,9,14 | MMP | |

| C | Intravasation | TAM; vasculature | PHD2 | ||

| D | Survival in circulation | Platelets | |||

| E | “Attraction” to new locations | Stromal cells | CXCR4 RANK | CXCL12 RANKL | |

| 2 | Implant into the Soil | ||||

| F | Arrest | Platelets; Endothelial cells | Lysophosphatidic acid, IL-6, IL-8; E-selectin, integrins, CD44, MUC1 | ||

| G | Extravasation | Endothelial cells | TGF-β, VEGF | Adhesion molecules | |

| H | Settlement | Stromal cells | CXCR4, MMP-2, MMP-9, Integrin αvβ3, αvβ5 CCR5 | CXCL12 Galectin-3/Thomsen-Fr Ag CCL5 | |

| 3 | Dormancy | CAF, NK cells | Osteomimicry | GAS6, BMP7, TGF-β2; INFγ, TRAIL-FASL | |

| 4 | Growth | Endothelial cells; Adipocites; Macrophages; MDSC and DC; TAN | Osteomimicry with osteoblast-like phenotype or osteoclast properties; VCAM1, NFkB | TGF-β1; periostin; FABP4; Cathepsin K; Collagen t.1, fibronectin | |

| I | Osteoclastic lesion | Pro-osteoclasts and osteoclasts; Myeloid cells and lymphocytes | VCAM1, PTHrP, DKK-1 | TGF-β, IGF-1 | |

| II | Slerotic lesions | Osteoblasts | OPG, BMP-2, Wnt, adrenomedullin, FGF9, PDGF, ET-1 | IL-6, MCP-1, VEGF, MIP-2 | |

| III | Mixed lesions | ||||

| Subtypes | N of Cases | Cellular Differentiation | Gene Expression | Ki-67 | PSA Level | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetA | 71% | Moderate cellular atypia, glandular differentiation | KLK3, FOXA1, KRT18, CDH1 | Low | High | Good |

| MetB | 17% | Prominent cellular atypia, lack of glandular differentiation | FOXM1, CCNB1-2, CDC25B, CDK1, PLK1, PKMYT1, LMB1, KNSL1, NCL, KRT18 and others | High | Low | Poor |

| MetC | 12% | Prominent cellular atypia, glandular differentiation detectable in some cases, relatively high stroma/epithelial ratio | ECM remodelling, regulation of EMT (Wnt, Notch, TGF-β, PDGF, immunological synapse formation, C/EBP, GSTP1 | Low | Low | Poor |

| Author | Trial | Drug | Setting | N° of Patients | OS | p-Value | Time to First SRE * | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tannock et al., 2004 [112] | TAX 327 | Docetaxel (3 weekly and w) + prednisone vs. Mitoxantrone (m) + prednisone | mCRPC | 1006 (335 vs. 334 vs. 337) | 18.9 vs. 17.4 vs. 16.5 | 0.009 (3 w vs. m); 0.36 (w vs. m) | No data | - |

| Sweeney et al., 2015 [131] | CHAARTED | Docetaxel + ADT vs. ADT | mHSPC | 790 (397 vs. 393) | 57.6 mo vs. 44.0 mo | <0.001 | No data | - |

| De Bono et al., 2010 [113] | TROPIC | Cabazitaxel + prednisone vs. Mitoxantrone (m) + prednisone | mCRPC | 755 (378 vs. 377) | 15.1 mo vs. 12.7 mo | <0.0001 | No data (bone pain 5% vs. 5%) | - |

| Logothetis et al., 2012 [117] | COU-AA-301 | Abiraterone + prednisone vs. placebo + prednisone | mCRPC | 1195 (797 vs. 398) | 15.8 mo vs. 11.2 mo | <0.0001 | 9.9 mo vs. 4.9 mo | 0.0001 |

| James et al., 2017 [119] | STAMPEDE | Abiraterone + prednisone + ADT vs. ADT | mHSPC and mCRPC | 1917 (960 vs. 957) | 83% vs 76% (3-year OS rate) | <0.001 | 12% of events vs. 22% of events | <0.001 |

| Fizazi et al., 2017 [127] | LATITUDE | Abiraterone + prednisone + ADT vs. placebo + ADT | mHSPC | 1199 (597 vs. 602) | not reached (NR) vs. 34.7 mo | <0.001 | NR vs NR | 0.009 |

| Scher et al., 2012 [120] | AFFIRM | Enzalutamide vs. placebo | mCRPC | 1199 (800 vs. 399) | 18.4 mo vs. 13.6 mo | <0.001 | 16.7 mo vs. 13.3 mo | <0.001 |

| Beer et al., 2014 [109] | PREVAIL | Enzalutamide vs. placebo | mCRPC | 1717 (872 vs. 845) | 32.4. mo vs. 30.2 mo | <0.001 | 32% events vs. 37% events | <0.001 |

| Armstrong et al., 2019 [129] | ARCHES | Ezalutamide + ADT vs. placebo + ADT | mHSPC | 1150 (574 vs. 576) | NR (HR 0.81) | 0.3361 | NR (HR 0.52) | 0.0026 |

| Davis et al., 2019 [130] | ENZAMET | Ezalutamide + standard care vs. standard care | mHSPC | 1125 (563 vs. 562) | NR (at 36 mo: 80% vs. 72%) | 0.002 | No data | - |

| Chi et al., 2019 [128] | TITAN | Apalutamide + ADT vs. placebo + ADT | mHSPC | 1052 (525 vs. 527) | NR (at 24 mo: 82.4% vs. 73.5%) | 0.005 | NR (HR 0.80) | - |

| Fizazi et al., 2019 [111] | ARAMIS | Darolutamide vs. placebo | non mCRPC | 1509 (955 vs. 554) | NR vs. NR | 0.045 | 16 events vs. 18 events | 0.01 |

| Parker et al., 2013 [114] | ALSYMPCA | Radium-223-dichloride vs. placebo | mCRPC | 921 (614 vs. 307) | 14.9 mo vs. 11.3 mo | <0.001 | 15.6 mo vs. 9.8 mo | <0.001 |

| Smith et al., 2019 [124] | ERA 223 | Radium-223-dichloride vs. placebo in addition to Abiraterone + prednisone | mCRPC and bone met | 806 (401 vs. 405) | 30.7 mo vs. 33.3 mo | 0.128 | 22.3 mo vs. 26.0 mo | 0.2636 |

| Sartor et al., 2021 [125] | VISION | 177Lu-PSMA-617 plus standard care vs. standard care | mCRPC | 831 (551 vs. 280) | 15.3 mo vs. 11.3 mo | <0.001 | 11.5 mo 6.8 mo | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baldessari, C.; Pipitone, S.; Molinaro, E.; Cerma, K.; Fanelli, M.; Nasso, C.; Oltrecolli, M.; Pirola, M.; D’Agostino, E.; Pugliese, G.; et al. Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Cancers 2023, 15, 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051518

Baldessari C, Pipitone S, Molinaro E, Cerma K, Fanelli M, Nasso C, Oltrecolli M, Pirola M, D’Agostino E, Pugliese G, et al. Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Cancers. 2023; 15(5):1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051518

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldessari, Cinzia, Stefania Pipitone, Eleonora Molinaro, Krisida Cerma, Martina Fanelli, Cecilia Nasso, Marco Oltrecolli, Marta Pirola, Elisa D’Agostino, Giuseppe Pugliese, and et al. 2023. "Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications" Cancers 15, no. 5: 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051518

APA StyleBaldessari, C., Pipitone, S., Molinaro, E., Cerma, K., Fanelli, M., Nasso, C., Oltrecolli, M., Pirola, M., D’Agostino, E., Pugliese, G., Cerri, S., Vitale, M. G., Madeo, B., Dominici, M., & Sabbatini, R. (2023). Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Cancers, 15(5), 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051518