Simple Summary

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are a common cancer, affecting both men and women, normally diagnosed through tissue biopsies in combination with imaging techniques and standardized biomarkers leading to patient selection for local or systemic therapies. Liquid biopsies (LBs)—due to their non-invasive nature as well as low risk—are the current focus of cancer research and could be a promising tool for early cancer detection and treatment surveillance, thus leading to better patient outcomes. In this review, we provide an overview of different types of LBs enabling early detection and monitoring of GI cancers and their clinical application.

Abstract

Worldwide, gastrointestinal (GI) cancers account for a significant amount of cancer-related mortality. Tests that allow an early diagnosis could lead to an improvement in patient survival. Liquid biopsies (LBs) due to their non-invasive nature as well as low risk are the current focus of cancer research and could be a promising tool for early cancer detection. LB involves the sampling of any biological fluid (e.g., blood, urine, saliva) to enrich and analyze the tumor’s biological material. LBs can detect tumor-associated components such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and circulating tumor cells (CTCs). These components can reflect the status of the disease and can facilitate clinical decisions. LBs offer a unique and new way to assess cancers at all stages of treatment, from cancer screenings to prognosis to management of multidisciplinary therapies. In this review, we will provide insights into the current status of the various types of LBs enabling early detection and monitoring of GI cancers and their use in in vitro diagnostics.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are responsible for more cancer-related deaths than lung and breast cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the major type of GI cancer, with 1.9 million new cases diagnosed worldwide in 2020, making it after lung and breast cancer the third most common cancer of all organs. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, in the same year, 1.1 million new cases of gastric cancer, 900,000 new cases of liver cancer, 600,000 new cases of esophageal cancer, and 500,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer were diagnosed across the globe [1].

Although the prognosis of many GI cancers has improved over the past decades [2,3], a late cancer diagnosis is still the leading reason for cancer-related deaths among all GI cancers [4]. Current research focuses therefore on improving early cancer diagnosis, possibly leading to better outcomes among all GI cancers [5,6]. So far, endoscopic or CT-guided solid biopsies in combination with so-called serum-based tumor biomarkers are primary methods for the diagnosis of GI cancers [7]. Thereby, solid biopsies are considered the gold standard strategy capable of classifying tumors, identifying the mutational status, and providing prognostic information. However, these methods have some limitations, e.g., obtaining insufficient or inaccurate tissue samples possibly leading to false-positive or false-negative results. In addition, tissue biopsies might cause harm to the patient. However, recent studies suggest tissue biopsies taken from a single cancer nodule or single metastatic lesion may fail to represent the entire tumor heterogeneity within the patient, possibly being one of the main reasons for the failure of current targeted therapies [8,9,10,11,12,13]. To date, several serum-based biomarkers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), carbohydrate antigen 72-4 (CA72-4), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), and alpha-feto protein (AFP) have been identified and widely used for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring of potential recurrence of GI cancers [14,15]. Although, due to the limit of specificity and sensitivity most of these biomarkers are not useful for early cancer detection [16]. Therefore, LB emerged as a promising tool for early detection, treatment selection, and real-time prognosis.

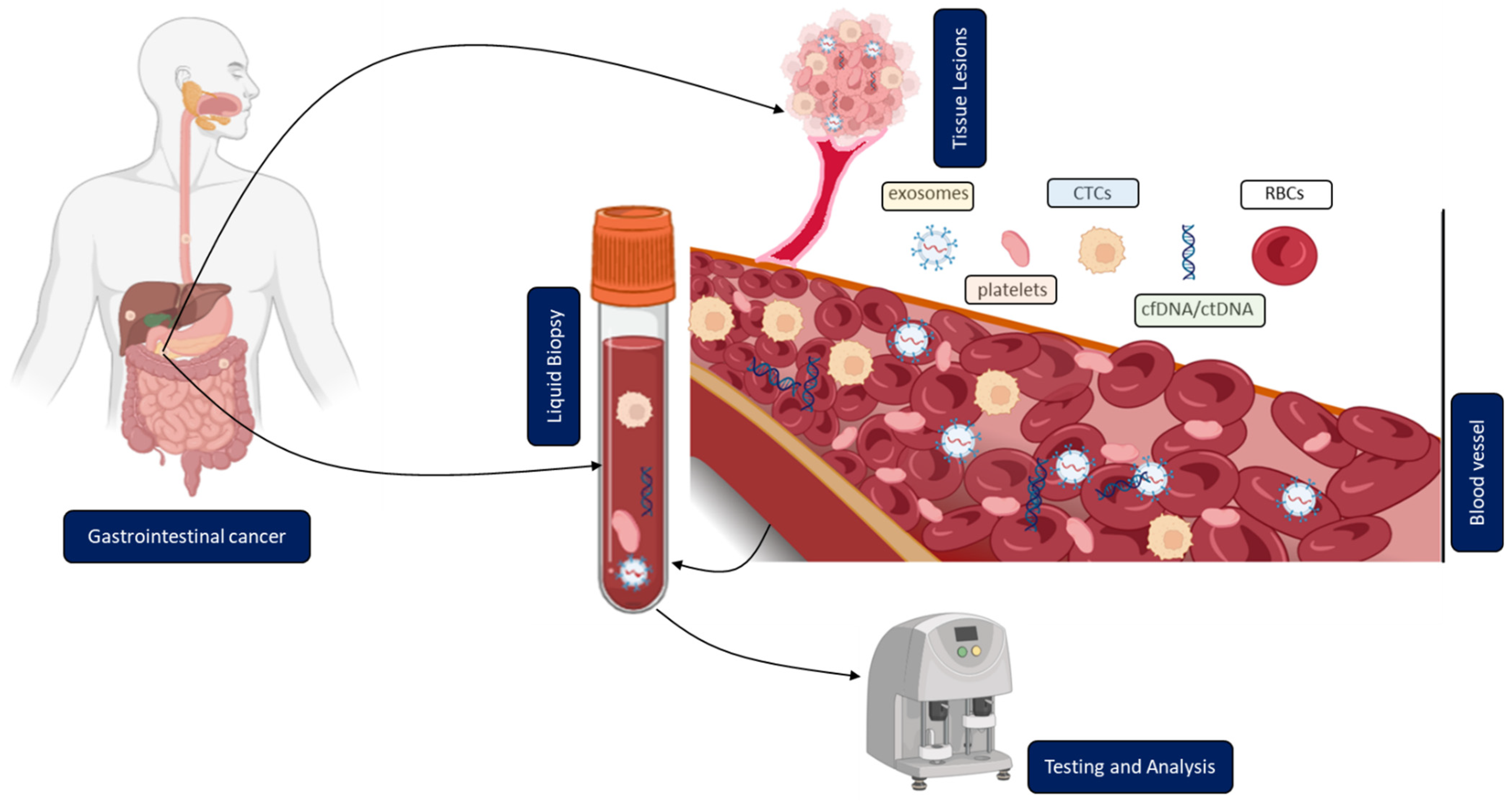

In contrast to solid biopsy, LB is a minimally invasive approach enabling the real-time monitoring and early uncovering of alterations in cells or cell products shed from malignant lesions into the body fluids (Figure 1). LB analysis can identify multiple heterogeneous resistance mechanisms in single patients compared to solid biopsy. Furthermore, LB facilitates the choice of the right treatment and observation of the treatment response. Due to the minimally invasive nature of LB, the resulting complications from obtaining solid biopsies could be prevented. A typical LB sample is taken from any biological fluid such as blood, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine. LB materials derived from peripheral blood have been investigated extensively. LB analysis from blood contains enrichment and isolation of CTCs, circulating blood platelets, ctDNA, and other tumor genetic material such as extracellular vesicles. As of today, several LB technologies have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for malignancies such as metastatic lung, breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer: CELLSEARCH CTC test using circulating tumor cells from Veridex, Guardant360 CDx, and FoundationOne Liquid CDx using circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and next-generation sequencing to detect tumor-specific mutations.

Figure 1.

Clinical application of liquid biopsy (LB) in gastrointestinal cancer (GICs). Circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cell-free or circulating tumor DNA (cfDNA/ctDNA), tumor-educated platelets (TEP), exosomes, and RBCs in the blood of GICs patients can be used as potential biomarkers for LBs and their expression levels can be measured to determine the clinical status of GICs patients.

Due to the crucial role of LB markers, our main focus is on research findings and clinical applications in gastrointestinal cancers.

2. Overview of Different Methodologies and Their Current Clinical Application

2.1. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

CTCs are tumor cells, shed from a primary tumor. They can enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, potentially spreading into distant organs possibly leading to metastases [17,18]. Nevertheless, only a minority of CTCs become solid metastatic lesions because of a complex sequence of events needed, i.e., the detachment from the primary tumor, migration through the circulating blood, immune escape, and survival. It remains unclear how the detachment process from the primary tumor tissue takes place. Evidence supports the involvement of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, by which transformed epithelial cells can acquire the ability to invade, resist apoptosis, and disseminate. This could be the main driver for the detachment of tumor cells from the primary tumor [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Other reports hypothesize that cells split into different clusters [25]. It is noteworthy that gastrointestinal cancers compared to breast cancer have lower numbers of CTCs in peripheral blood due to portal vein circulations and a steady ‘first-pass effect’ in the liver [26]. Therefore, portal vein blood might be a unique sample site to isolate CTCs from gastrointestinal cancers. It has already been shown that the number of enriched CTCs from portal vein blood is higher than in the systemic circulation [27,28]. Portal vein blood can be collected intraoperatively or even by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling [29].

In addition to the number of CTCs, the analysis of physical (size, density, and electric charge) and biological (cell surface expression) properties could play a crucial role in future clinical use [30].

2.1.1. Isolation and Enrichment of CTCs

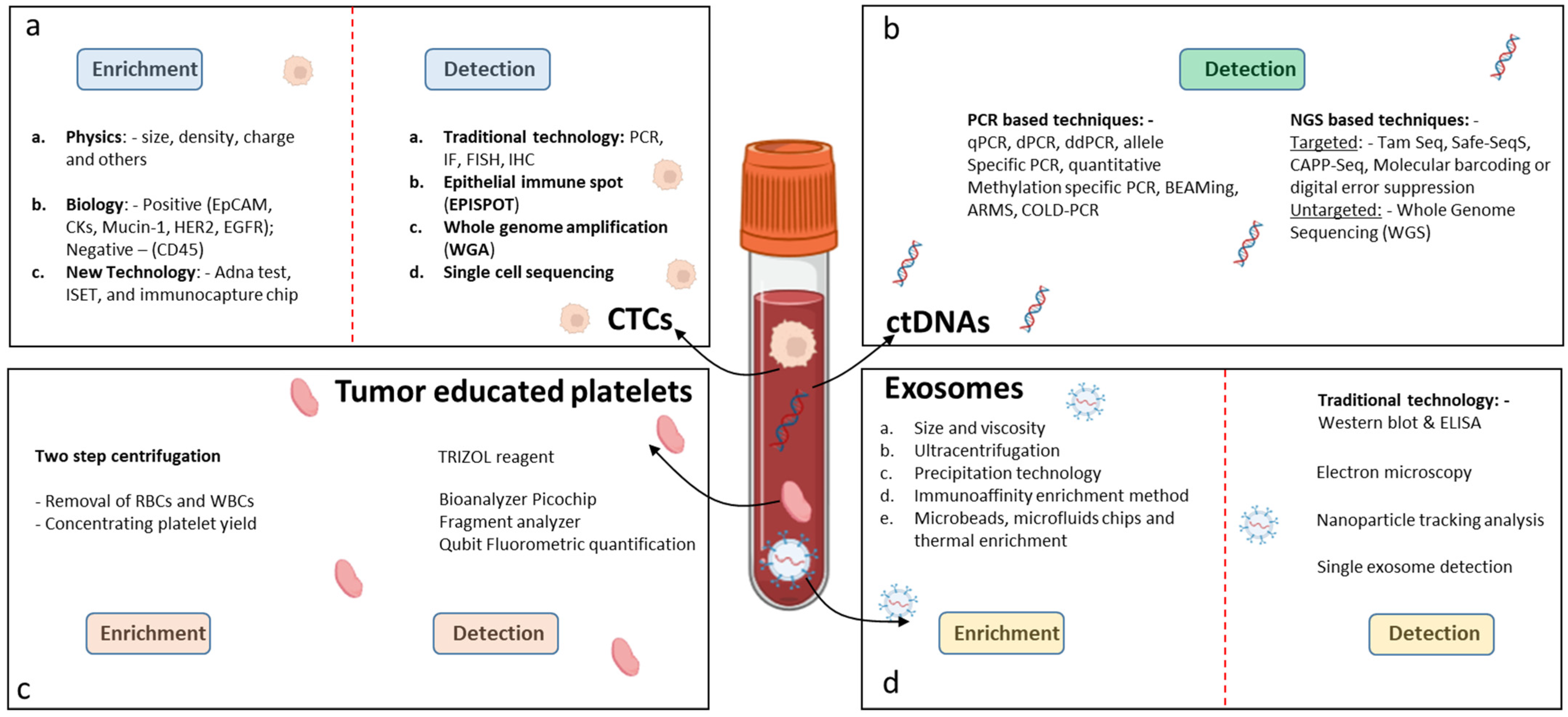

The isolation and enrichment of CTCs are technically challenging because of their low numbers and elimination by the body’s immune system. The sensitivity of capture methods has improved in the last few years. First, based on cancer-specific characteristics, the cancer cells are separated from other blood components followed by enrichment procedures. There are two main techniques for isolating CTCs, one based on immunoaffinity properties, and the other based on biophysical properties. The immunoaffinity-based technology, including positive or negative selection assays, isolates CTCs with an antibody-immobilized inert surface combined with magnetic beads [31] (Figure 2a). The epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a commonly used cell surface marker for positive CTC selection and an immunomagnetic assay called CELLSEARCH®. To date, CELLSEARCH® is the only CTC technology that has gained FDA approval enabling the direct visualization and quantification of CTCs and the identification of living cells without the need for cell lysis. The functionality of CELLSEARCH® for the detection of CTCs in GI cancer was confirmed by different studies [32,33]. In another approach, CTCs from blood samples of patients with CRC were pre-enriched through binding to VAR2CSA protein-coupled magnetic beads, and finally the colon-related mRNA transcripts USH1C and CKMT1A were detected by RT-qPCR [34]. Microfluidic chips as an immunoaffinity technology allow the selection of CTCs from small volumes of fluid under laminar flow, eliminating the need for sample processing. In a study by Lim et al. [35], single CTCs and CTC clusters were captured on the membrane of a centrifugal microfluidic device, picked without fixation, and used for further molecular analysis. Researchers began to develop CTC isolation technologies based on the biophysical properties of CTCs to overcome the bias and narrow spectrum of immunoaffinity-based approaches for CTC isolation. These methods are characterized as label-free and isolate CTCs from the blood based on biophysical properties, such as density, size, deformability, and electrical charge [36]. In order to confirm that the enriched cells consist only of CTCs, the cells must undergo characterization. Currently, this is achieved by immunocytochemistry-based assays, including immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry, and molecular approaches, including RT-qPCR, FISH, and next-generation sequencing [37]. Using GILUPI Cell Collector (CC), a novel in vivo CTC detection device, researchers reported overcoming the limitations of small blood sample volumes. However, the clinical relevance of the CTCs detected was inferior to the CTCs identified by Cell Search [38].

Figure 2.

Techniques for detection of LB biomarkers in GICs. (a) Detection of CTCs, (b) detection of ctDNAs, (c) detection of tumor-educated platelets, and (d) detection of exosomes.

2.1.2. Clinical Application/Relevance of CTCs

Several studies have observed the prognostic value of CTCs for overall survival (OS) in localized colorectal cancer (CRC) [39,40]. In a series of 287 patients, a group demonstrated that preoperative CTC detection with a ≥ 1 CTC/7.5 mL proved to be an independent prognostic marker, whereas another group with 519 patients stated no association after surgery [39,41]. In high-risk CRC patients requiring adjuvant chemotherapy, CTC detection in the blood was correlated with worse outcomes [41,42,43]. A meta-analysis containing 1847 patients (11 studies) indicated that the detection of CTCs in the peripheral blood with CELLSEARCH® has predictive utility for patients with CRC [44]. VISNÚ-1, a multicentre, randomized phase III trial with 349 patients, indicated that the first-line FOLFOXIRI-bevacizumab chemotherapy regimen significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) in comparison to the FOLFOX-bevacizumab chemotherapy regimen in patients with metastatic CRC. This trial revealed that the CTC count might be a valuable non-invasive biomarker to aid in decision-making for patients undergoing intensive first-line therapy [45]. In a series of studies performed in metastatic CRC, patients with high baseline CTC count (≥3 CTCs/7.5 mL) could benefit from intensive chemotherapy regimens (four drugs), unlike patients with low CTC counts [44,46,47,48]. The PRODIGE 17 trial, conducted in 106 untreated patients with advanced gastric and esophageal cancer, reported that dynamic changes in CTC counts between baseline and 28 days after treatment were significantly associated with PFS and OS and could help in tailoring treatment regimens to each individual patient [49]. The above-mentioned findings might therefore help in the development of individualized treatment approaches in gastrointestinal cancer patients. In Table 1, a broad application of CTCs and its clinical relevance in GICs is mentioned.

Table 1.

Clinical relevance of CTCs in GICs.

2.2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

A group of French scientists detected cfDNA fragments in the circulating plasma of patients with autoimmune disorders in 1948 [73]. Later it became clear that the release of cfDNA is not restricted to autoimmune disorders, but was also found amongst others in pregnant women [74], septic patients [75], people suffering from different types of cancers, and even in healthy individuals [76]. Numerous studies have been conducted to uncover the mechanisms by which DNA fragments are released from cells into the plasma or serum. Major mechanisms involve apoptosis, necrosis, phagocytosis, NETosis, or active secretion [77]. Basically, every cell and tissue type is able to release cfDNA into circulation. Consequently, based on cell and tissue-specific methylation patterns from comprehensive databases including the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) an assignment of cfDNA to different origins became possible [78]. Accordingly, the major source of cfDNA in blood results from hematopoietic cells, followed by vascular endothelial cells (up to 10%). However, cfDNA from liver tissue can also frequently be detected at low levels in circulation (up to 1%) in healthy people [78]. CtDNA is a fraction of cfDNA that originates from primary tumors, metastases, or from CTCs. Additionally, some findings are suggestive of an active release of ctDNA from living tumor cells involving exosomes [79]. CtDNA is characterized by small 70–200 base pair fragments circulating freely within the blood [73] showing a major fragment size of around 170 base pairs, which corresponds to nucleosomal fragments resulting from apoptosis [80]. The half-life of ctDNA is very short ranging from 15 min to 2.5 h before it is finally cleared by the liver and/or kidneys which is a prerequisite for a precise biomarker [81]. Concentrations of ctDNA in the blood of patients with a malignant tumor are significantly increased compared to healthy individuals [82]; however, levels of released ctDNA significantly vary between different tumor types and tumor stages. Furthermore, the match of cancer-specific alterations in the genome of solid tumors to those of ctDNA is a major discriminator between ctDNA and physiological cell-free DNA at steady state [83,84,85].

2.2.1. Detection and Analysis of ctDNA

There are a number of technical challenges associated with the analysis of ctDNA. First, total cfDNA itself is present only at comparably low concentrations in the nanogram per ml range. Second, the fraction of ctDNA among total cfDNA in many cases is also relatively low. This becomes especially evident in the early stages of cancer development or for tumors that release only low amounts of DNA [76]. Therefore, an urgent need for enrichment approaches of ctDNA over total cfDNA still exists. In this context, it has been reported that ctDNA to some extent might be enriched in cfDNA fractions of smaller size (90–150 base pairs (bp)) separated from the major fraction of 170 bp fragments [86] (Figure 2b). Although a tendency to higher ctDNA content in the 90–150 bp fraction could be found, enrichment factors of twofold in more than 95% of cases were still not satisfying [86]. In principle, a plethora of downstream analyses has been established for the diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, and prediction of treatment response for all major cancer diseases. Among them are single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) as well as copy number variation (CNV) analyses. When sufficient amounts of ctDNA templates (at least one genome equivalent per assay) are available in patient specimens, targeted assays based on PCR, for example, represent powerful approaches. Such PCR-based techniques which are characterized by high sensitivity showed the ability to identify relevant alterations in genes including RAS, HER2/NEU, BRAF, MET, BRCA2, APC, TP53, ALK, ROS1, PTEN, and NF1. However, when ctDNA content drops below one tumor genome equivalent per assay multi-target approaches become mandatory. Multi-gene panels are well established to similarly test for hundreds of targets. However, when it comes to early detection of cancer for screening purposes ctDNA contents of less than 0.01% represent a serious technical challenge to robustly assure high sensitivity and specificity. Cancer-specific methylomes in ctDNA were therefore proposed as a promising alternative [87]. In combination with next-generation sequencing (NGS), thousands of differential hyper-/hypo-methylated regions (DMRs) have been determined for a variety of cancers in addition to chromosomal and copy number changes or point mutations [88,89]. Accordingly, complex signatures of DMRs, for example, allow for early diagnosis with higher reliability. In general, it has been suggested that even for only as low as 0.01% ctDNA content prediction of cancer disease should be possible with 100–1000 DMRs when sequencing coverage of at least 100–1000x is given [87].

2.2.2. Clinical Application/Relevance of ctDNA

Analysis of tumor-linked genetic alterations and DNA methylation profiling has been recognized as a method for detecting potential biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis [90]. In a study by Tam et al. [91] the levels of TAC1 and SEPT9 methylation detected in postoperative sera of patients with CRC were independent predictors for tumor recurrence and unfavorable cancer-specific survival. Findings from several studies showed that high ctDNA levels combined with an increased number of mutations detected in the ctDNA were linked to poor survival and multi-site metastasis [92]. However, when the amount of ctDNA was <1 mutant template molecule per milliliter of plasma, tests fail to detect early-stage cancer [93]. Therefore, methylome analyses of cfDNA with thousands of cancer-specific DMRs might overcome such limitations. In 2019, the ‘Galleri test’ or the ‘Galleri multicancer early detection (MCED) test’ developed by GRAIL Inc. (Menlo Park, CA, USA) achieved Breakthrough Device designation. The Galleri test detects cancer- and tissue-specific alterations in the methylation patterns of cfDNA in a blood sample via NGS, which should allow early pan-cancer detection even for cancers with unknown primary. GRAIL’s clinical trial includes three studies: the Circulating Cell-free Genome Atlas (CCGA) Study (Clinical Trial NCT02889978) [94], the STRIVE Study (Clinical Trial NCT03085888), and the SUMMIT Study (Clinical Trial NCT03934866). In these studies including 2482 cancer patients covering approximately 50 different cancer types, sensitivities and specificities were tested by using a target hybridization capture approach for the analyses of 100,000 differentially methylated regions [95]. In a predefined subset of 12 cancer types which comprised roughly 63% of all US cancer cases average sensitivity was 67.3% accumulated for stage I–III at a very high specificity of 99.3% [95]. Sensitivity for all 50 cancer types accumulated for stage I–III dropped to 43.9% with 18% sensitivity for stage I and 43% in stage II. Remarkably, sensitivities for pancreatic cancer were significantly higher even at early stages with 63% and 83% in stage I and II, respectively. Although high specificities might predestine this test for negative prediction in screening approaches, moderate sensitivities still require improvements, especially for early diagnosis. Another FDA-approved LB-based test is Epi proColon® (Epigenomics AG, Berlin, Germany) targeting methylation changes used to screen for CRC. The test is based on a real-time PCR with a fluorescent hydrolysis probe and targets the methylation changes of the SEPT9 gene promoter in cfDNA isolated from plasma. To evaluate the clinical assessment, Epi proColon® was involved in a prospective multicenter study (Clinical Trial NCT00855348) [96,97,98].

A ctDNA-guided approach has been used by numerous clinical trials (DYNAMIC, CIRCULATE-Japan, CIRCULATE-trial, CIRCULATE-PRODIGE, and IMPROVE-IT2), all focused towards precise adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancer patients [99,100,101,102,103]. According to DYNMAIC-trial, a ctDNA-guided approach led to a reduction in the number of patients who received adjuvant therapy, and furthermore, ctDNA-positive patients appeared to benefit from adjuvant treatment. The other trials (CIRCULATE-trial, IMPROVE-IT2) mentioned above could help in decision-making before adjuvant treatment in stage II colon cancer. The outcome of these trials proposes that a survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy may be obtained in a well-defined subgroup of patients with stage II colon cancer—especially those with detectable ctDNA post-surgery. In the case of pancreatic cancer, ctDNA might be used as a marker for monitoring treatment efficacy and disease progression [104]. To prove the feasibility of a non-invasive detection in plasma, Liu et al. developed a pancreatic cancer detection assay (PANDA) for screening and validation of PDAC-specific DNA methylation in tissues and plasmas of PDAC patients [105]. In combination with age and CA19-9 plasma serum level, this assay showed encouraging results to discriminate PDAC plasma from non-malignant disease, showing its capability to be amended into a non-invasive diagnostics method for PDAC screening. In Table 2, a broad application of ctDNA/cfDNA and its clinical relevance in GICs is mentioned.

Table 2.

Clinical relevance of ctDNA/cfDNA in GICs.

2.3. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles (Tumor Exosomes)

Exosomes are a subpopulation of extracellular vesicles (EVs), ranging in size from 30–150 nm. They are derived from the endosomal pathway via the formation of late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (MVBs). As an important mediator of intracellular communication, exosomes transmit various biological molecules including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids over distances within the protection of a lipidic bilayer-enclosed structure. Nearly all types of cells and all body fluids contain exosomes [124,125]. Cancer cells and other stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) also release exosomes and control tumor development through molecular exchanges mediated by exosomes [126,127]. Circulating extracellular vesicles (cEVs) are implied to be more stable in comparison to serological proteins as the lipidic bilayers defend the content from proteases and other enzymes [128].

2.3.1. Isolation of Tumor Exosomes

Exosomes can be isolated using various methodologies. Ultracentrifugation (UC) is the most widely used technique. Other techniques include differential centrifugation (DC), density gradient ultrafiltration (DG), size exclusion chromatography (SEC), precipitation, immunoaffinity capture based on the expression of endosomal surface proteins such as CD81, CD63, and CD9, and microfluidic-based assays [129] (Figure 2d).

2.3.2. Clinical Application/Relevance of Tumor Exosomes

Exosomes demonstrate significant advantages over other sources of LBs. First, exosomes exist in almost all body fluids and are characterized by highly stable lipidic bilayers. Second, living cells secret exosomes. They thus contain biological information from the parental cells and are more representative than cell-free DNA secreted during necrosis or apoptosis [130]. Third, exosomes express specific proteins such as CD63, ALIX, TS101, and HSP70, 20 which can be used as markers to discriminate exosomes from other vesicles making their identification clear and simple [131]. Fourth, as exosomes can present specific surface proteins from parental cells or target cells, they can help in the prediction of organ-specific metastasis [132]. Fifth, compared to CTCs, they can be isolated using classic methods such as ultracentrifugation [133].

Circulating exosomal PD-L1 was shown to contribute to immunosuppression, to reflect the immune status, and to better predict survival in patients with GICs, thereby making it a potential prognostic biomarker [134]. Additionally, EV proteins such as carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs), Tenascin C, Glypican-1, and ZIP-4 have been recognized as diagnostic biomarkers in GICs [135,136,137]. The EV-Glypican-1 (GPC-1) derived from plasma has been described as a potential marker of early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with higher diagnostic accuracy than CA19-9 [137]. A clinical trial (NCT03032913) performed by Etienne BUSCAIL involved 20 PDAC patients and 20 non-cancer patients, whose blood samples were collected to detect CTCs and GPC1+ exosomes for diagnostic accuracy assessment of CTCs and Onco-exosome Quantification. Very recently, Lin et al. presented the development of a signature of four EV-proteins—monocyte marker CD14, Serpin A4 (a regulator of angiogenesis), CFP (a positive regulator of the complement system), and LBP (lipopolysaccharide binding protein)—as prognostic biomarkers in colorectal liver metastases (CRLM). Thereby, they used matching pre- and post-operative serum samples of patients undergoing CRLM surgery and finally validated the discovered proteins in three independent cohorts. Additionally, they showed that EV-bound CXCL7 could serve as a biomarker of early response in CRML patients undergoing systemic chemotherapy [138]. Furthermore, three cancer-specific phospholipids were found in a study that analyzed 20 dysregulated phospholipids in pancreatic cancer compared to controls. Among them, LysoPC 22:0 was linked with tumor stage, whereas CA19-9 and CA242 were associated with tumor diameter and positive lymph node count [139]. Finally, diagnostic accuracy for WASF2, ARF6 mRNAs, SNORA74A, and SNORA25snoRNAs in circulating exosomes was greater than for CA19-9 in discriminating PC patients from controls [140]. Even though a limited number of studies on the application of exosome-based drug delivery vectors in the treatment of GICs exist, some of them report intriguing advancements in the field. Using an in vitro model Pascucci L. et al. demonstrated the role of exosomal-mesenchymal stromal cells (exo-MSCs) in the packaging and delivery of active drugs, suggesting a possible option of using the MSCs as a warehouse to develop drugs with a better specificity [141]. Another study showed the application of milk-derived exosomes for the oral delivery of PAC in early-stage and advanced-stage pancreatic and other cancers. It also evaluated the anti-tumor potency of the milk-derived exosomes loaded with PAC [142]. Furthermore, studies have verified the link between cancer-derived exosomes and the modulation of immune response in pancreatic cancer and have also indicated the application of these cargo carriers in targeting pancreatic cancer cells, whether as anti-tumor drugs and other molecules, such as RNAi against mutant KRAS [143]. More applications and the clinical relevance of exosomes are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical relevance of Exosomes in GICs.

2.4. Tumor-Educated Blood Platelets (TEPs)

Platelets play a central role in blood coagulation and in the healing of wounds, and their relationship with cancer has been extensively investigated [156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164]. There are two major studies that indicated the involvement of platelets during tumor progression. These studies contributed to the development of the concept of tumor-educated platelets (TEPs). The first study by Trousseau (1868) observed spontaneous coagulation being common in cancerous patients, stating that circulating platelets were affected by cancer [165]. The second study (Billroth T, 1877) described ‘’ thrombi filled with specific tumor elements’’ as part of metastasis, pointing out a direct interaction of cancer cells and platelets [166,167]. In recent years, several studies have focused on the impact of platelets during cancer progression, and some of them showed that platelet dysfunction and thrombotic disorders are important key factors in cancer development. By now it is well known that tumor-educated platelets (TEPs) are educated when they interact with the tumor cells in such a way as to lead to the detachment of biomolecules, such as proteins and RNA, tumor-specific splice events, and finally to megakaryocyte alteration [168]. Through this interaction, the RNA profile of blood platelets changes. This change has been used as an independent diagnostic marker for detecting TEPs in various solid tumors [169]. The RNA biomarkers of the directly transferred transcripts are EGFRvIII, PCA3, EML4-ALK, KRAS, EGFR, PIK3CA mutants, FOLH1, KLK2, KLK3, and NPY [170]. Here, we describe the isolation, detection, and clinical relevance of TEPsin GICs.

2.4.1. Isolation and Detection of Tumor-Educated Platelets

Tumor-educated platelets can be separated from peripheral blood by using a two-step centrifugation approach [171]. The first step separates the platelet-rich plasma (PRP) from the red blood and white blood cells, whereas the second centrifugation step yields the platelet pellet [172]. For the detection of the TEPs in the human plasma, the plasma pellets are dissolved in 1ml TRIZOL reagent. RNA is extracted from the plasma platelet pellet and the suboptimal quality of the platelet RNA is characterized by an absence of ribosomal 18S and 28S peaks and measured in a Bioanalyzer Picochip. Preferably, platelet mRNAs are measured by other methods, such as Fragment analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Ankeny, IA, USA) or Qubit Fluorometric Quantification (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) analysis (Figure 2c).

2.4.2. Clinical Application/Relevance of Tumor-Educated Blood Platelets

Platelet-related measures are considered important in anticipating long-term results in patients with GI cancer. A study distinguished 228 patients with localized and metastasized tumors from 55 healthy donors using the genetic profile of mRNA from TEPs. Additionally, mRNA sequencing of TEPs could accurately recognize MET or ERBB2-positive and mutant KRAS, EGFGR, or PIK3CA tumors. Moreover, TEPs have the ability to identify the location of primary tumors including colorectal cancer, non-small lung carcinoma, glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, hepatobiliary cancer, and breast cancer [169]. Yang et al. showed that TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1) mRNA levels were higher in platelets from patients with CRC compared to those from healthy donors or patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, which could be another promising diagnostic signature [173]. A study in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) conducted by Asghar et al. showed that the expression of TGF-β, NF-κβ, and VEGF was increased in TEPs of HCC patients compared to that from controls and thereby they suggested that these RNA based biomarkers could be used as a promising tool for early detection of HCC [174]. Furthermore, the alterations of platelet counts as a prognostic marker were studied in a clinical trial (NCT03717519) conducted by Corrado Pedrazzani. The study recruited 196 patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), Ishibashi et al. performed a meta-analysis evaluating the prognostic values of platelet-related measures. The analysis revealed that a high platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) was significantly correlated with poor OS [175]. A dual-center retrospective study performed by Yang et al. showed a standardized indicator of platelet counts was used to forecast the prognosis of 586 CRC patients by using a development-validation cohort. In the development cohort, postoperative platelet count and postoperative/preoperative platelet ratio (PPR) were independent predictors of prognosis in CRC patients. In the validation cohort, the platelet/lymphocyte ratio and PPR were used to test the OS of CRC patients and showed the largest AUC in reviewing 1-year and 3-year OS (AUC: 0.663 and 0.673) [176]. Based on the studies above, we summarize that PLR and PPR could serve as reliable and economic indicators to evaluate the prognosis of GI cancer. Interestingly, many new approaches have been utilized to explore the clinical relevance of TEPs in GICs. We have summarized some of them in Table 4 below. TEPs have advantages over other blood-based sources due to their abundance in the blood, the ease with which they can be isolated, their high-quality RNA, and their ability to process RNA in response to foreign signals.

Table 4.

Clinical relevance of tumor-educated platelets in GICs.

3. Conclusions

Due to the limitations of conventional tissue biopsies, there is an urgent need for new tumor biomarkers. As reviewed here, LBs have been well-evaluated and show promising results as an alternative clinical tool for the detection and treatment of gastrointestinal cancers, many of those currently being intensively investigated in various observational and interventional clinical trials (Table 5 and Table 6). Multiple longitudinal biopsies allow for real-time monitoring of the tumor. This approach may facilitate the prediction of the possible treatment outcome and may help in choosing the optimal individualized therapeutic strategy. Therefore, the analysis of LB markers (TEPs, CTCs, ctDNA/cfDNA, and exosomes), in combination with modern imaging techniques and already existing protein markers might help to create an optimal clinical synergy that might be used as a standard procedure in the near future for early cancer detection and individualized cancer treatment.

Table 5.

Observational study with ongoing clinical trials of LB in GICs.

Table 6.

Interventional study with ongoing clinical trials of LBs in GICs.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: P.D., A.M., D.K. and G.F.W.; Collection and assembly of data: P.D., A.M., D.K., A.A. and G.F.W.; Methodology: P.D., A.M., D.K. and A.A.; Writing and editing: P.D., A.M., D.K., A.A., C.K., K.S. and G.F.W.; Administrative support: G.F.W.; Final approval of manuscript: All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Das Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF, 03INT506CA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AdSCs | adult stem cells |

| ALI | air-liquid-interface |

| CA19-9 | carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 |

| CEACAMs | carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| CRML | colorectal liver metastases |

| circRNA | circular RNA |

| CTCs | circulating tumor cells |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| DC | differential centrifugation |

| ddPCR | droplet digital PCR |

| DG | density gradient ultracentrifugation |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EpCAM | epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| EUS | endoscopic ultrasound |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| FDA | the United States Food and Drug Administration |

| FISH | fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| GPC-1 | glypican 1 |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| LB | liquid biopsy |

| LncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| mRNA | messenger RNA |

| MVBs | multivesicular bodies |

| miRNA | microRNAs |

| NGS | next generation sequencing |

| PC | pancreatic cancer |

| PDAC | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PDO | patient-derived cancer organoid |

| PSCs | pluripotent stem cells |

| RT-qPCR | real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SEC | size exclusion chromatography |

| TEPs | tumor-educated blood platelets |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| UC | ultracentrifugation |

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Estimated Number of New Cases and Deaths of Cancer in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Le, Q.; Wang, C.; Shi, Q. Meta-Analysis on the Improvement of Symptoms and Prognosis of Gastrointestinal Tumors Based on Medical Care and Exercise Intervention. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5407664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-D.; Zhang, P.-F.; Xi, H.-Q.; Wei, B.; Chen, L.; Tang, Y. Recent Advances in the Diagnosis, Staging, Treatment, and Prognosis of Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Literature Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 744839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Neale, R.E.; Vignat, J.; Giovannucci, E.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Bray, F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 335–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Pershad, Y.; Albadawi, H.; Kuo, M.; Alzubaidi, S.; Naidu, S.; Knuttinen, M.-G.; Oklu, R. Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimi, K.; Ishibashi, R.; Mitsui, T.; Aikou, S.; Kodashima, S.; Yamashita, H.; Yamamichi, N.; Hirata, Y.; Fujishiro, M.; Seto, Y.; et al. Laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery for gastrointestinal tumor. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garraway, L.A.; Jänne, P.A. Circumventing Cancer Drug Resistance in the Era of Personalized Medicine. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, L.; Saha, S.K.; Liu, L.Y.; Siravegna, G.; Leshchiner, I.; Ahronian, L.G.; Lennerz, J.K.; Vu, P.; Deshpande, V.; Kambadakone, A.; et al. Polyclonal Secondary FGFR2 Mutations Drive Acquired Resistance to FGFR Inhibition in Patients with FGFR2 Fusion–Positive Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Siravegna, G.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Corti, G.; Crisafulli, G.; Ahronian, L.G.; Mussolin, B.; Kwak, E.L.; Buscarino, M.; Lazzari, L.; et al. Tumor Heterogeneity and Lesion-Specific Response to Targeted Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.; Math, M.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; Stewart, A.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazar-Rethinam, M.; Kleyman, M.; Han, G.C.; Liu, D.; Ahronian, L.G.; Shahzade, H.A.; Chen, L.; Parikh, A.R.; Allen, J.N.; Clark, J.W.; et al. Convergent Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome the Heterogeneity of Acquired Resistance in BRAF(V600E) Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.; Overman, M.; Dasari, A.; Kazmi, S.; Mazard, T.; Vilar, E.; Morris, V.; Lee, M.; Herron, D.; Eng, C.; et al. Characterizing the patterns of clonal selection in circulating tumor DNA from patients with colorectal cancer refractory to anti-EGFR treatment. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emoto, S.; Ishigami, H.; Yamashita, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kaisaki, S.; Kitayama, J. Clinical significance of CA125 and CA72-4 in gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Gastric Cancer 2011, 15, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, M.; Shen, L. Predictive value of serum CEA, CA19-9 and CA72.4 in early diagnosis of recurrence after radical resection of gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2011, 58, 2166–2170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimada, H.; Noie, T.; Ohashi, M.; Oba, K.; Takahashi, Y. Clinical significance of serum tumor markers for gastric cancer: A systematic review of literature by the Task Force of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Gastric Cancer 2013, 17, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.C. Circulating tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, I.; David, P.; Gerken, G.G.H.; Schlaak, J.F.; Hoffmann, A.-C. Role of circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymkowsky, M.W.; Savagner, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A cancer researcher’s conceptual friend and foe. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, K.; Weinberg, R.A. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: Acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.J.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Development and Disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, M.; Christofori, G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrallo-Gimeno, A.; Nieto, M.A. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: Implications in development and cancer. Development 2005, 132, 3151–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6897–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denève, E.; Riethdorf, S.; Ramos, J.; Nocca, D.; Coffy, A.; Daurès, J.-P.; Maudelonde, T.; Fabre, J.-M.; Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Capture of Viable Circulating Tumor Cells in the Liver of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, Y.W.; Kuo, H.C.; Ho, B.I.; Chang, M.C.; Chang, Y.T.; Cheng, M.F.; Chen, H.-L.; Liang, T.-Y.; Wang, C.-F.; Huang, C.-Y.; et al. A High Circulating Tumor Cell Count in Portal Vein Predicts Liver Metastasis from Periampullary or Pancreatic Cancer: A High Portal Venous CTC Count Predicts Liver Metastases. Medicine 2016, 95, e3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissolati, M.; Sandri, M.T.; Burtulo, G.; Zorzino, L.; Balzano, G.; Braga, M. Portal vein-circulating tumor cells predict liver metastases in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014, 36, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.G.; Waxman, I. EUS-Guided Portal Venous Sampling of Circulating Tumor Cells. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Circulating tumor cells: Liquid biopsy of cancer. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahneh, F.Z. Sensitive antibody-based CTCs detection from peripheral blood. Hum. Antibodies 2013, 22, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uenosono, Y.; Arigami, T.; Kozono, T.; Yanagita, S.; Hagihara, T.; Haraguchi, N.; Matsushita, D.; Hirata, M.; Arima, H.; Funasako, Y.; et al. Clinical significance of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood from patients with gastric cancer. Cancer 2013, 119, 3984–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.T.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Park, Y.S.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K. Circulating Tumor Cells are Predictive of Poor Response to Chemotherapy in Metastatic gastric cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2015, 30, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang-Christensen, S.R.; Katerov, V.; Jørgensen, A.M.; Gustavsson, T.; Choudhary, S.; Theander, T.G.; Salanti, A.; Allawi, H.T.; Agerbæk, M. Detection of VAR2CSA-Captured Colorectal Cancer Cells from Blood Samples by Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR. Cancers 2021, 13, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Park, S.; Jeong, H.-O.; Park, S.H.; Kumar, S.; Jang, A.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.U.; Cho, Y.-K. Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters Are Cloaked with Platelets and Correlate with Poor Prognosis in Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; McFaul, S.M.; Duffy, S.P.; Deng, X.; Tavassoli, P.; Black, P.C.; Ma, H. Technologies for label-free separation of circulating tumor cells: From historical foundations to recent developments. Lab A Chip 2013, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgård, O.; Tjensvoll, K.; Gilje, B.; Søreide, K. Circulating tumour cells and DNA as liquid biopsies in gastrointestinal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, e110–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdar, L.; Fluegen, G.; van Dalum, G.; Honisch, E.; Neves, R.P.; Niederacher, D.; Neubauer, H.; Fehm, T.; Rehders, A.; Krieg, A.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in colorectal cancer patients using the GILUPI CellCollector: Results from a prospective, single-center study. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, U.; Rahbari, N.N.; Schölch, S.; Reissfelder, C.; Kahlert, C.; Büchler, M.W.; Weitz, J.; Koch, M. Circulating tumour cells and outcome in non-metastatic colorectal cancer: A prospective study. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalum, G.; Stam, G.J.; Scholten, L.F.; Mastboom, W.J.; Vermes, I.; Tibbe, A.G.; De Groot, M.R.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Importance of circulating tumor cells in newly diagnosed colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, M.J.; Sastre, J.; Maestro, M.L.; Veganzones, S.; Viéitez, J.M.; Alonso, V.; Grávalos, C.; Escudero, P.; Vera, R.; Aranda, E.; et al. Role of circulating tumor cells as prognostic marker in resected stage III colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 26, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-Y.; Tsai, H.-L.; Uen, Y.-H.; Hu, H.-M.; Chen, C.-W.; Cheng, T.-L.; Lin, S.-R.; Wang, J.-Y. Circulating tumor cells as a surrogate marker for determining clinical outcome to mFOLFOX chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-J.; Wang, P.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.-W.; Shen, N. Meta-analysis Reveals the Prognostic Value of Circulating Tumour Cells Detected in the Peripheral Blood in Patients with Non-Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gao, P.; Song, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z. Meta-analysis of the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells detected with the CellSearch System in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, E.; Viéitez, J.M.; Gómez-España, A.; Calle, S.G.; Salud-Salvia, A.; Graña, B.; Garcia-Alfonso, P.; Rivera, F.; Quintero-Aldana, G.A.; Reina-Zoilo, J.J.; et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFOX plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and >/=3 circulating tumour cells: The randomised phase III VISNU-1 trial. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardingham, J.E.; Grover, P.; Winter, M.; Hewett, P.J.; Price, T.J.; Thierry, B. Detection and Clinical Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Colorectal Cancer—20 Years of Progress. Mol. Med. 2015, 21 (Suppl. S1), S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, M.G.; Renehan, A.G.; Backen, A.; Gollins, S.; Chau, I.; Hasan, J.; Valle, J.W.; Morris, K.; Beech, J.; Ashcroft, L.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Enumeration in a Phase II Trial of a Four-Drug Regimen in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2014, 14, 115–122.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, G.; Schölch, S.; Koch, M.; Weitz, J. Biology and significance of circulating and disseminated tumour cells in colorectal cancer. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2012, 397, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernot, S.; Badoual, C.; Terme, M.; Castan, F.; Cazes, A.; Bouche, O.; Bennouna, J.; Francois, E.; Ghiringhelli, F.; De La Fouchardiere, C.; et al. Dynamic evaluation of circulating tumour cells in patients with advanced gastric and oesogastric junction adenocarcinoma: Prognostic value and early assessment of therapeutic effects. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 79, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.M.; Kim, G.H.; Jeon, H.K.; Kim, D.H.; Jeon, T.Y.; Park, D.Y.; Jeong, H.; Chun, W.J.; Kim, M.-H.; Park, J.; et al. Circulating tumor cells detected by lab-on-a-disc: Role in early diagnosis of gastric cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Tong, G.; Wu, X.; Cai, W.; Li, Z.; Tong, Z.; He, L.; Yu, S.; Wang, S. Enumeration Aand Characterization Of Circulating Tumor Cells And Its Application In Advanced Gastric Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 7887–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, R.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J.; Kong, X.; Liang, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, T.; et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression on cell-surface vimentin-positive circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer patients. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhi, J.H.; Kim, G.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, D.U.; Lee, M.W.; Lee, B.E.; Kwon, C.H.; Cho, Y.-K. Circulating Tumor Cells and TWIST Expression in Patients with Metastatic Gastric Cancer: A Preliminary Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Zhu, S.; Luo, Y.; Li, G.; Pu, Y.; Cai, B.; Zhang, C. Application of Circulating Tumor Cells and Circulating Free DNA from Peripheral Blood in the Prognosis of Advanced Gastric Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 9635218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Hu, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, H. Circulating tumor cells as an independent prognostic factor in advanced colorectal cancer: A retrospective study in 121 patients. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnassy, A.A.; Salem, S.E.; Mohanad, M.; Abulezz, N.Z.; Abdellateif, M.S.; Hussein, M.; Zekri, C.A.; Zekri, A.-R.N.; Allahloubi, N.M. Prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in Egyptian non-metastatic colorectal cancer patients: A comparative study for four different techniques of detection (Flowcytometry, CellSearch, Quantitative Real-time PCR and Cytomorphology). Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2018, 106, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaritakis, I.; Sfakianaki, M.; Papadaki, C.; Koulouridi, A.; Vardakis, N.; Koinis, F.; Hatzidaki, D.; Georgoulia, N.; Kladi, A.; Kotsakis, A.; et al. Prognostic significance of CEACAM5mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iinuma, H.; Watanabe, T.; Mimori, K.; Adachi, M.; Hayashi, N.; Tamura, J.; Matsuda, K.; Fukushima, R.; Okinaga, K.; Sasako, M.; et al. Clinical Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells, Including Cancer Stem-Like Cells, in Peripheral Blood for Recurrence and Prognosis in Patients with Dukes’ Stage B and C Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, J.; Koopman, M.; Miller, M.C.; Tibbe, A.; Cats, A.; Creemers, G.J.M.; Vos, A.H.; Nagtegaal, I.; Terstappen, L.; Punt, C.J.A. Circulating tumour cells early predict progression-free and overall survival in advanced colorectal cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and targeted agents. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 21, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.J.A.; Punt, C.J.; Iannotti, N.; Saidman, B.H.; Sabbath, K.D.; Gabrail, N.Y.; Picus, J.; Morse, M.; Mitchell, E.; Miller, M.C.; et al. Relationship of Circulating Tumor Cells to Tumor Response, Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3213–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasoppokakorn, T.; Buntho, A.; Ingrungruanglert, P.; Tiyarattanachai, T.; Jaihan, T.; Kulkraisri, K.; Ariyaskul, D.; Phathong, C.; Israsena, N.; Rerknimitr, R.; et al. Circulating tumor cells as a prognostic biomarker in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaoka, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Mashima, H.; Ohdan, H. Clinical significance of glypican-3-positive circulating tumor cells of hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A prospective study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Yang, X.R.; Sun, Y.F.; Shen, M.N.; Ma, X.L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, B.; et al. Clinical significance of EpCAM mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma by an optimized negative enrichment and qRT-PCR-based platform. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4794–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cao, L.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.-F.; Qian, H.-H.; Kang, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.; Shi, L.-H.; et al. Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using a Novel Cell Separation Strategy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3783–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.Y.; Li, F.; Li, T.T.; Zhang, J.T.; Shi, X.J.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Z.-Y.; Huang, Z.-L. A clinically feasible circulating tumor cell sorting system for monitoring the progression of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd, P.; Hou, S.; Court, C.M.; Lee, Y.-T.; Chen, P.-J.; Zhu, Y.; Sadeghi, S.; Finn, R.S.; Teng, P.-C.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma–Circulating Tumor Cells Expressing PD-L1 Are Prognostic and Potentially Associated with Response to Checkpoint Inhibitors. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, B.; Yang, Y.; Ge, N.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Qian, H.; et al. pERK/pAkt phenotyping in circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for sorafenib efficacy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 7, 2646–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemenetzis, G.; Groot, V.; Yu, J.; Ding, D.; Teinor, J.; Javed, A.; Wood, L.; Burkhart, R.; Cameron, J.; Makary, M.; et al. Circulating tumor cells dynamics in pancreatic adenocarcinoma correlate with disease status: Results of the prospective cluster study. HPB 2019, 21, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeth, E.; Grigoleit, U.; Moellmann, B.; Röder, C.; Schniewind, B.; Kremer, B.; Kalthoff, H.; Vogel, I. Detection of tumor cell dissemination in pancreatic ductal carcinoma patients by CK 20 RT-PCR indicates poor survival. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 131, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Yuan, Z. Clinical significance of pancreatic circulating tumor cells using combined negative enrichment and immunostaining-fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, C.; Ankeny, J.S.; Sho, S.; Winograd, P.; Hou, S.; Song, M.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Girgis, M.D.; Graeber, T.G.; Agopian, V.G.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Occult Metastatic Disease and Prognosis in Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franses, J.W.; Philipp, J.; Missios, P.; Bhan, I.; Liu, A.; Yashaswini, C.; Tai, E.; Zhu, H.; Ligorio, M.; Nicholson, B.; et al. Pancreatic circulating tumor cell profiling identifies LIN28B as a metastasis driver and drug target. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, P.; Metais, P. Nuclear Acids in Human Blood Plasma. Comptes Rendus Seances Soc. Biol. Ses Fil. 1948, 142, 241–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Y.M.; Lau, T.K.; Zhang, J.; Leung, T.N.; Chang, A.M.; Hjelm, N.M.; Elmes, R.S.; Bianchi, D.W. Increased fetal DNA concentrations in the plasma of pregnant women carrying fetuses with trisomy 21. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 1747–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumaz, S.; Stevens, P.; Grumaz, C.; Decker, S.O.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Brenner, T.; von Haeseler, A.; Sohn, K. Next-generation sequencing diagnostics of bacteremia in septic patients. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Pol, Y.; Mouliere, F. Toward the Early Detection of Cancer by Decoding the Epigenetic and Environmental Fingerprints of Cell-Free DNA. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucamp, J.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Badenhorst, C.P.S.; Pretorius, P.J. The diverse origins of circulating cell-free DNA in the human body: A critical re-evaluation of the literature. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Magenheim, J.; Neiman, D.; Zemmour, H.; Loyfer, N.; Korach, A.; Samet, Y.; Maoz, M.; Druid, H.; Arner, P.; et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlert, C.; Melo, S.; Protopopov, A.; Tang, J.; Seth, S.; Koch, M.; Zhang, J.; Weitz, J.; Chin, L.; Futreal, A.; et al. Identification of Double-stranded Genomic DNA Spanning All Chromosomes with Mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the Serum Exosomes of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3869–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 256, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, M.; Schmidt, B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer—A survey. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2007, 1775, 181–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, S.A.; Shapiro, B.; Sklaroff, D.M.; Yaros, M.J. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. 1977, 37, 646–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lyberopoulou, A.; Aravantinos, G.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Nikiteas, N.; Bouziotis, P.; Isaakidou, A.; Papalois, A.; Marinos, E.; Gazouli, M. Mutational Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells from Colorectal Cancer Patients and Correlation with Primary Tumor Tissue. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinugasa, H.; Nouso, K.; Miyahara, K.; Morimoto, Y.; Dohi, C.; Tsutsumi, K.; Kato, H.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, K. Detection of K-ras gene mutation by liquid biopsy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebofsky, R.; Decraene, C.; Bernard, V.; Kamal, M.; Blin, A.; Leroy, Q.; Frio, T.R.; Pierron, G.; Callens, C.; Bieche, I.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a non-invasive substitute to metastasis biopsy for tumor genotyping and personalized medicine in a prospective trial across all tumor types. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 9, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouliere, F.; Chandrananda, D.; Piskorz, A.M.; Moore, E.K.; Morris, J.; Ahlborn, L.B.; Mair, R.; Goranova, T.; Marass, F.; Heider, K.; et al. Enhanced detection of circulating tumor DNA by fragment size analysis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Singhania, R.; Fehringer, G.; Chakravarthy, A.; Roehrl, M.H.A.; Chadwick, D.; Zuzarte, P.C.; Borgida, A.; Wang, T.T.; Li, T.; et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature 2018, 563, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Dronov, O.I.; Khomenko, D.I.; Huguet, F.; Louvet, C.; Mariani, P.; Stern, M.-H.; Lantz, O.; Proudhon, C.; Pierga, J.-Y.; et al. Clinical applications of circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Kasi, P.M.; Mody, K. Feasibility and clinical value of circulating tumor DNA testing in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, e16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Martínez-Cardús, A.; Sayols, S.; Musulén, E.; Balañá, C.; Estival-Gonzalez, A.; Moutinho, C.; Heyn, H.; Diaz-Lagares, A.; de Moura, M.C.; et al. Epigenetic profiling to classify cancer of unknown primary: A multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, C.; Chew, M.; Soong, R.; Lim, J.; Ang, M.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Ong, S.Y.K.; Liu, Y. Postoperative serum methylation levels of TAC1 and SEPT9 are independent predictors of recurrence and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 3131–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siveke, J.T.; Lueong, S.; Hinke, A.; Herbst, A.; Tannapfel, A.; Reinacher-Schick, A.C.; Kolligs, F.T.; Hegewisch-Becker, S. Serial analysis of mutant KRAS in circulation cell-free DNA (cfDNA) of patients with KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: A translational study of the KRK0207 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, e15599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Klein, E.; Hubbell, E.; Maddala, T.; Aravanis, A.; Beausang, J.; Filippova, D.; Gross, S.; Jamshidi, A.; Kurtzman, K.; et al. Plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) assays for early multi-cancer detection: The circulating cell-free genome atlas (CCGA) study. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Oxnard, G.R.; Klein, E.A.; Swanton, C.; Seiden, M.V.; CCGA Consortium. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, S.R.; Church, T.R.; Wandell, M.; Rösch, T.; Osborn, N.; Snover, D.; Day, R.W.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Rex, D.K. Endoscopic Detection of Proximal Serrated Lesions and Pathologic Identification of Sessile Serrated Adenomas/Polyps Vary on the Basis of Center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, T.R.; Wandell, M.; Lofton-Day, C.; Mongin, S.J.; Burger, M.; Payne, S.R.; Castaños-Vélez, E.; Blumenstein, B.A.; Rösch, T.; Osborn, N.; et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2013, 63, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taryma-Leśniak, O.; Sokolowska, K.E.; Wojdacz, T.K. Current status of development of methylation biomarkers for in vitro diagnostic IVD applications. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lahouel, K.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Lee, M.; Harris, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Kotani, D.; Yukami, H.; Mishima, S.; Sawada, K.; Shirasu, H.; Ebi, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Aleshin, A.; et al. CIRCULATE-Japan: Circulating tumor DNA–guided adaptive platform trials to refine adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 2915–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folprecht, G.; Reinacher-Schick, A.; Tannapfel, A.; Weitz, J.; Kossler, T.; Weiss, L.; Aust, D.E.; Von Bubnoff, N.; Kramer, M.; Thiede, C. Circulating tumor DNA-based decision for adjuvant treatment in colon cancer stage II evaluation: (CIRCULATE-trial) AIO-KRK-0217. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, TPS273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, J.; Benhaim, L.; Puig, P.L.; Le Malicot, K.; Emile, J.F.; Geillon, F.; Tougeron, D.; Manfredi, S.; Chauvenet, M.; Taly, V.; et al. Decision for adjuvant treatment in stage II colon cancer based on circulating tumor DNA: The CIRCULATE-PRODIGE 70 trial? Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nors, J.; Henriksen, T.V.; Gotschalck, K.A.; Juul, T.; Søgaard, J.; Iversen, L.H.; Andersen, C.L. IMPROVE-IT2: Implementing noninvasive circulating tumor DNA analysis to optimize the operative and postoperative treatment for patients with colorectal cancer—Intervention trial 2. Study protocol. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjensvoll, K.; Lapin, M.; Buhl, T.; Oltedal, S.; Berry, K.S.-O.; Gilje, B.; Søreide, J.A.; Javle, M.; Nordgård, O.; Smaaland, R. Abstract 5241: Clinical relevance of circulating tumor DNA in plasma from pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Ma, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Dai, M.; Shen, S.; Wu, H.M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA methylation as markers for early detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Lam, V.K.; Shi, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, F.; et al. Deep sequencing of circulating tumor DNA detects molecular residual disease and predicts recurrence in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Cristescu, R.; Bass, A.J.; Kim, K.-M.; Odegaard, J.I.; Kim, K.; Liu, X.Q.; Sher, X.; Jung, H.; Lee, M.; et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Lefterova, M.I.; Artyomenko, A.; Kasi, P.M.; Nakamura, Y.; Mody, K.; Catenacci, D.V.; Fakih, M.; Barbacioru, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. Validation of Microsatellite Instability Detection Using a Comprehensive Plasma-Based Genotyping Panel. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 7035–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.-T.; Chen, M.-H.; Fang, W.-L.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Jhang, F.-Y.; Yang, S.-H.; Lin, J.-K.; Chen, W.-S.; Jiang, J.-K.; et al. Clinical relevance of cell-free DNA in gastrointestinal tract malignancy. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 3009–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Ju, S.; Qi, J.; Zhao, J.; Shen, X.; Jing, R.; Yu, J.; Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Alu-based cell-free DNA: A novel biomarker for screening of gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 54037–54045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, D.G.; Park, M.K.; Baik, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. Circulating cell-free DNA as a promising biomarker in patients with gastric cancer: Diagnostic validity and significant reduction of cfDNA after surgical resection. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2014, 86, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M.A.L.; Lerner, L.; Abdelfatah, E.; Shankar, N.; Canner, J.K.; Hasan, N.M.; Yaghoobi, V.; Huang, B.; Kerner, Z.; Takaesu, F.; et al. Promoter methylation of ADAMTS1 and BNC1 as potential biomarkers for early detection of pancreatic cancer in blood. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, V.; Kim, D.U.; Lucas, F.A.S.; Castillo, J.; Allenson, K.; Mulu, F.C.; Stephens, B.M.; Huang, J.; Semaan, A.; Guerrero, P.A.; et al. Circulating Nucleic Acids Are Associated with Outcomes of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 108–118.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Springer, S.; Kinde, I.; Silliman, N.; Tacey, M.; Wong, H.-L.; Christie, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 346ra92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Elsaleh, H.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Yip, D.; et al. Serial circulating tumour DNA analysis during multimodality treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: A prospective biomarker study. Gut 2018, 68, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesato, Y.; Sasahira, N.; Ozaka, M.; Sasaki, T.; Takatsuki, M.; Zembutsu, H. Evaluation of circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker in pancreatic cancer with liver metastasis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrasz, D.; Pécuchet, N.; Garlan, F.; Didelot, A.; Dubreuil, O.; Doat, S.; Imbert-Bismut, F.; Karoui, M.; Vaillant, J.-C.; Taly, V.; et al. Plasma Circulating Tumor DNA in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Is a Prognostic Marker. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Okamura, R.; Fanta, P.; Patel, C.; Lanman, R.B.; Raymond, V.M.; Kato, S.; Kurzrock, R. Clinical correlates of blood-derived circulating tumor DNA in pancreatic cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, E.; Totoki, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Morizane, C.; Nara, S.; Hama, N.; Suzuki, M.; Furukawa, E.; Kato, M.; Hayashi, H.; et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA for molecular assessment in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.; Raymond, V.M.; Geis, J.A.; Collisson, E.A.; Jensen, B.V.; Hermann, K.L.; Erlander, M.G.; Tempero, M.; Johansen, J.S. Ultrasensitive plasma ctDNA KRAS assay for detection, prognosis, and assessment of therapeutic response in patients with unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 97769–97786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrus, G.; Kosirorek, H.; Sonbol, M.B.; Kusne, Y.; Uson, P.L.S.; Borad, M.J.; Ahn, D.H.; Kasi, P.M.; Drusbosky, L.M.; Dada, H.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Testing and Actionable Findings in Patients with Advanced and Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Oncol. 2021, 26, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausen, M.; Phallen, J.; Adleff, V.; Jones, S.; Leary, R.J.; Barrett, M.T.; Anagnostou, V.; Parpart-Li, S.; Murphy, D.; Kay Li, Q.; et al. Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Lipton, L.; Cohen, J.; Tie, J.; Javed, A.; Li, L.; Goldstein, D.; Burge, M.; Cooray, P.; Nagrial, A.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a potential marker of adjuvant chemotherapy benefit following surgery for localized pancreatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C. Exosomes: Secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2011, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Sharples, R.A.; Scicluna, B.J.; Hill, A.F. Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, J. Microparticles in Cancer. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.L.; San, R.S.; Wickline, S.A. Exosomes Released by Melanoma Cells Prepare Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Tumor Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3792–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. Exosomal proteins as potential markers of tumor diagnosis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangsupree, T.; Multia, E.; Riekkola, M.-L. Modern isolation and separation techniques for extracellular vesicles. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1636, 461773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Janku, F.; Zhan, Q.; Fan, J.-B. Accessing Genetic Information with Liquid Biopsies. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Greening, D.W.; Zhu, H.-J.; Takahashi, N.; Simpson, R.J. Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: Toward clinical application. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G.; Clayton, A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2006, 30, 3.22.1–3.22.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Che, X.; Qu, J.; Hou, K.; Wen, T.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 Retains Immunosuppressive Activity and is Associated with Gastric Cancer Prognosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 3745–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Hernandez, J.M.; Doussot, A.; Bojmar, L.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Costa-Silva, B.; Van Beek, E.J.A.H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Askan, G.; et al. Extracellular matrix proteins and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules characterize pancreatic duct fluid exosomes in patients with pancreatic cancer. HPB 2018, 20, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Meng, X.; Wu, M.; Han, J.; Tan, X. Exosomal zinc transporter ZIP4 promotes cancer growth and is a novel diagnostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 2946–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.A.; Luecke, L.B.; Kahlert, C.; Fernandez, A.F.; Gammon, S.T.; Kaye, J.; LeBleu, V.S.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Weitz, J.; Rahbari, N.; et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 523, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Baenke, F.; Lai, X.; Schneider, M.; Helm, D.; Polster, H.; Rao, V.S.; Ganig, N.; Wong, F.C.; Seifert, L.; et al. Comprehensive proteomic profiling of serum extracellular vesicles in patients with colorectal liver metastases identifies a signature for non-invasive risk stratification and early-response evaluation. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Si, D.; Xiu, D.; Zhong, L. Metabolomics identifies serum and exosomes metabolite markers of pancreatic cancer. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T.; Taniuchi, K.; Tsuboi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Kohsaki, T.; Okabayashi, T.; Saibara, T. Circulating pancreatic cancer exosomal RNA s for detection of pancreatic cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 13, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, L.; Coccè, V.; Bonomi, A.; Ami, D.; Ceccarelli, P.; Ciusani, E.; Viganò, L.; Locatelli, A.; Sisto, F.; Doglia, S.M.; et al. Paclitaxel is incorporated by mesenchymal stromal cells and released in exosomes that inhibit in vitro tumor growth: A new approach for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2014, 192, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Aqil, F.; Jeyabalan, J.; Spencer, W.A.; Beck, J.; Gachuki, B.W.; Alhakeem, S.S.; Oben, K.; Munagala, R.; Bondada, S.; et al. Milk-derived exosomes for oral delivery of paclitaxel. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, I.A.; Melo, S.A. Exosomes and the Future of Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Wang, J.; Dong, W.; Dai, K.; Du, J. Exosomal miRNA Expression Profiling and the Roles of Exosomal miR-4741, miR-32, miR-3149, and miR-6727 on Gastric Cancer Progression. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1263812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Shen, W.; Zou, H.; Lv, Q.; Shao, P. Circulating exosomal long non-coding RNA H19 as a potential novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520934297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, P.; Gao, H.; Xie, X.; Lu, P. Plasma Exosomal hsa_circ_0015286 as a Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Gastric Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022, 28, 1610446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Mao, J.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Sun, Z.; Qian, H.; et al. Exosomal TRIM3 is a novel marker and therapy target for gastric cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, Y.; Geng, B.; Xu, Y.; Miao, X.; Chen, L.; Mu, X.; Pan, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, T.; Wang, C.; et al. Helicobacter pylori -induced exosomal MET educates tumour-associated macrophages to promote gastric cancer progression. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 5708–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostenfeld, M.S.; Jensen, S.G.; Jeppesen, D.K.; Christensen, L.L.; Thorsen, S.B.; Stenvang, J.; Nielsen, H.J.; Thomsen, A.; Mouritzen, P.; Rasmussen, M.H.; et al. miRNA profiling of circulating EpCAM+ extracellular vesicles: Promising biomarkers of colorectal cancer. J. Extracell Vesicles 2016, 5, 31488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julich-Haertel, H.; Urban, S.K.; Krawczyk, M.; Willms, A.; Jankowski, K.; Patkowski, W.; Kruk, B.; Krasnodębski, M.; Ligocka, J.; Schwab, R.; et al. Cancer-associated circulating large extracellular vesicles in cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Dong, X.; Gao, J.; Liu, F.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, X. A novel rapid quantitative method reveals stathmin-1 as a promising marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, L.; Gong, M.; Su, G.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, L.; et al. Protein Profiling and Sizing of Extracellular Vesicles from Colorectal Cancer Patients via Flow Cytometry. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavisotto, C.C.; Cappello, F.; Macario, A.J.; de Macario, E.C.; Logozzi, M.; Fais, S.; Campanella, C. Exosomal HSP60: A potentially useful biomarker for diagnosis, assessing prognosis, and monitoring response to treatment. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 17, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, L.; Jia, Z.; Peng, Z.; Tang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, B.; Wang, L.; et al. GPC1 exosome and its regulatory miRNAs are specific markers for the detection and target therapy of colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ng, T.K.; Zhao, C.; Gan, Q.; Gu, X.; Xiang, J. Circulating exosomal CPNE3 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.W.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Weinberg, R.A. Emerging Biological Principles of Metastasis. Cell 2017, 168, 670–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]