A Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Solid Tumor Brain Metastases That Have Progressed Following Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Eligibility

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Statistical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

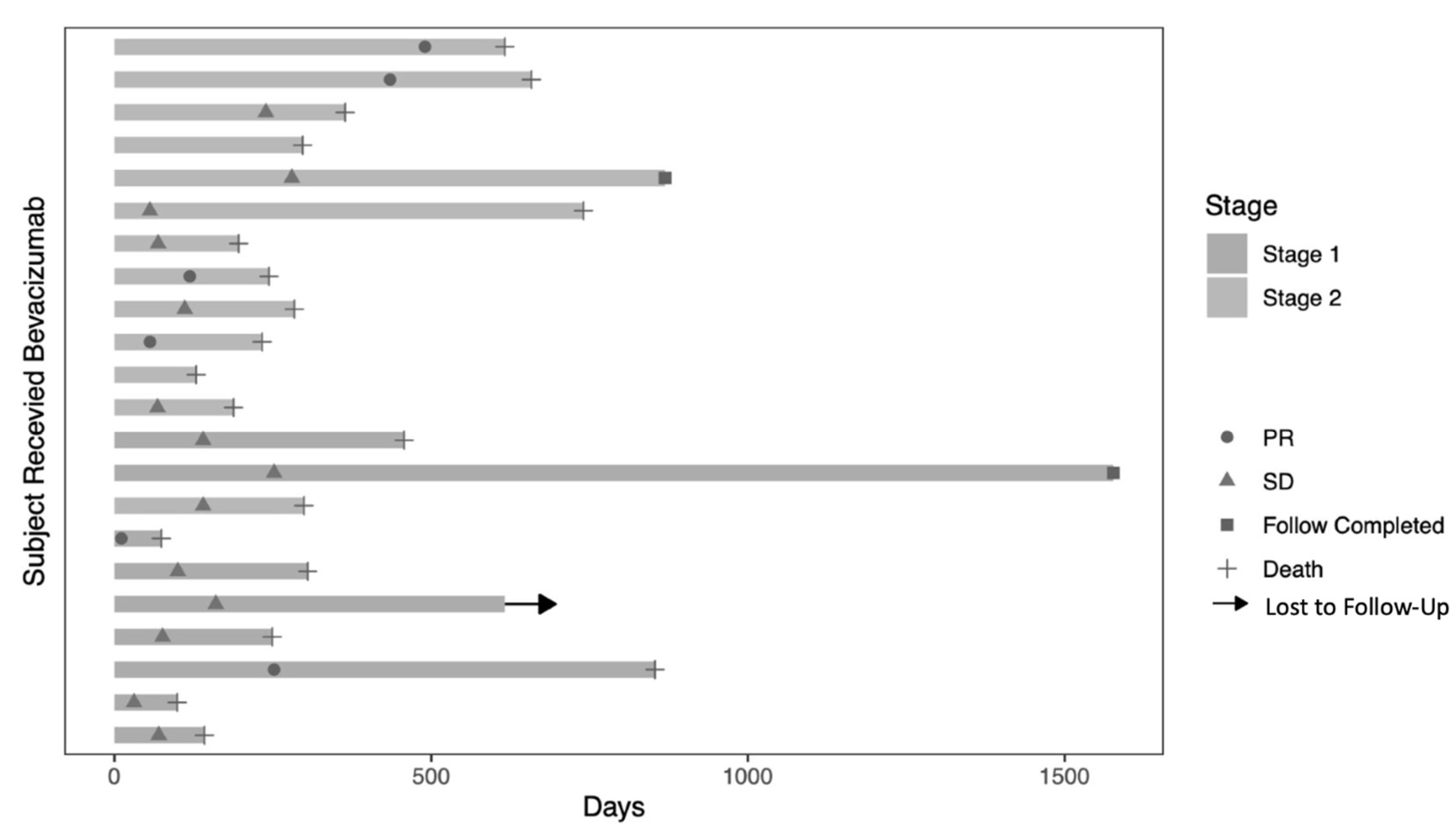

3.2. Radiologic Response

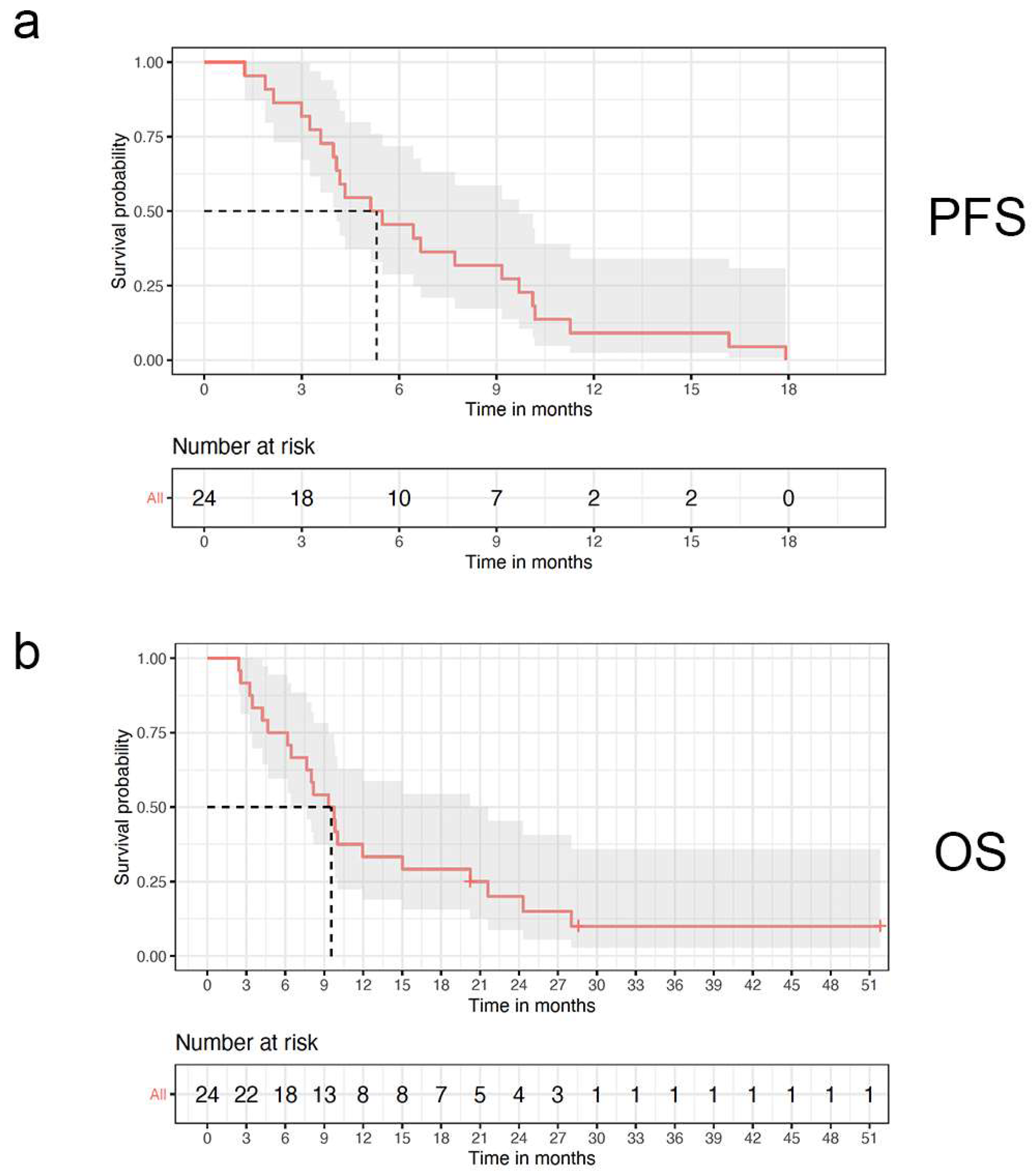

3.3. Survival

3.4. Safety

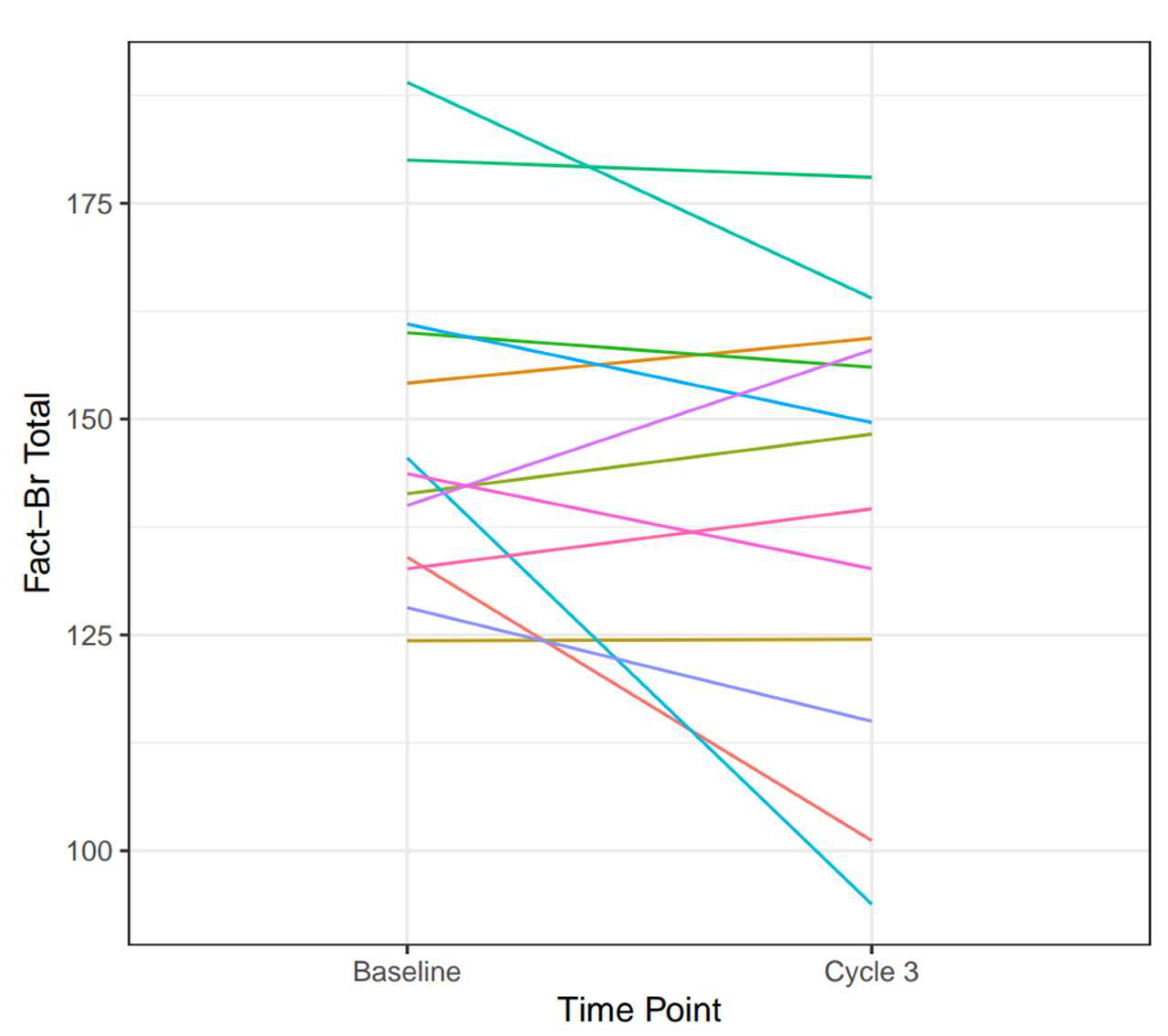

3.5. Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayak, L.; Lee, E.Q.; Wen, P.Y. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 14, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperduto, P.W.; Kased, N.; Roberge, D.; Xu, Z.; Shanley, R.; Luo, X.; Sneed, P.K.; Chao, S.T.; Weil, R.J.; Suh, J.; et al. Summary report on the graded prognostic assessment: An accurate and facile diagnosis-specific tool to estimate survival for patients with brain metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.H.; Kotecha, R.; Chao, S.T.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Sahgal, A.; Chang, E.L. Current approaches to the management of brain metastases. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The blood-brain barrier and blood-tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwak, H.-S.; Yoo, H.J.; Youn, S.-M.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, M.S.; Rhee, C.H. Radiosurgery for recurrent brain metastases after whole-brain radiotherapy: Factors affecting radiation-induced neurological dysfunction. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2009, 45, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammirati, M.; Cobbs, C.S.; Linskey, M.E.; Paleologos, N.A.; Ryken, T.C.; Burri, S.H.; Asher, A.L.; Loeffler, J.S.; Robinson, P.D.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. The role of retreatment in the management of recurrent/progressive brain metastases: A systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2010, 96, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langston, J.; Patil, T.; Camidge, D.R.; Bunn, P.A.; Schenk, E.L.; Pacheco, J.M.; Jurica, J.; Waxweiler, T.V.; Kavanagh, B.D.; Rusthoven, C.G. CNS Downstaging: An Emerging Treatment Paradigm for Extensive Brain Metastases in Oncogene-Addicted Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2023, 178, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popat, S.; Ahn, M.-J.; Ekman, S.; Leighl, N.B.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Siva, S.; Tsuboi, M.; Wu, Y.-L.; Yang, J.C.-H. Osimertinib for EGFR-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Central Nervous System Metastases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives on Therapeutic Strategies. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 9–24, Correction in Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.U.; Murthy, R.K.; Abramson, V.; Anders, C.; Bachelot, T.; Bedard, P.L.; Borges, V.; Cameron, D.; Carey, L.A.; Chien, A.J.; et al. Tucatinib vs Placebo, Both in Combination with Trastuzumab and Capecitabine, for Previously Treated ERBB2 (HER2)-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with Brain Metastases: Updated Exploratory Analysis of the HER2CLIMB Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 9, 197–205, Correction in JAMA Oncol. 2022, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilanti, E.; Brastianos, P.K. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Brain Metastases: A Primer for Neurosurgeons. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, E281–E288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odia, Y.; Shih, J.H.; Kreisl, T.N.; Fine, H.A. Bevacizumab-related toxicities in the National Cancer Institute malignant glioma trial cohort. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 120, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessurun, C.A.C.; Hulsbergen, A.F.C.; de Wit, A.E.; Tewarie, I.A.; Snijders, T.J.; Verhoeff, J.J.C.; Phillips, J.G.; Reardon, D.A.; Mekary, R.A.; Broekman, M.L.D. The combined use of steroids and immune checkpoint inhibitors in brain metastasis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, W.; Wang, S. Efficacy of bevacizumab in the treatment of refractory brain edema of metastatic tumors from different sources. Neurol. Res. 2021, 43, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavarajah, N.; Bedard, G.; Zhang, L.; Cella, D.; Beaumont, J.L.; Tsao, M.; Barnes, E.; Danjoux, C.; Sahgal, A.; Soliman, H.; et al. Psychometric validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy—Brain (FACT-Br) for assessing quality of life in patients with brain metastases. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, E.N.; Brown, B.W. Confidence limits for probability of response in multistage phase II clinical trials. Biometrics 1985, 41, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoccianti, S.; Ricardi, U. Treatment of brain metastases: Review of phase III randomized controlled trials. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 102, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperduto, P.W.; Mesko, S.; Li, J.; Cagney, D.; Aizer, A.; Lin, N.U.; Nesbit, E.; Kruser, T.J.; Chan, J.; Braunstein, S.; et al. Survival in Patients with Brain Metastases: Summary Report on the Updated Diagnosis-Specific Graded Prognostic Assessment and Definition of the Eligibility Quotient. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3773–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logie, N.; Jimenez, R.B.; Pulenzas, N.; Linden, K.; Ciafone, D.; Ghosh, S.; Xu, Y.; Lefresne, S.; Wong, E.; Son, C.H.; et al. Estimating prognosis at the time of repeat whole brain radiation therapy for multiple brain metastases: The reirradiation score. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 2, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikov, E.; Bezjak, A.; Yi, Q.-L.; Wells, W.; Dawson, L.; Millar, B.-A.; Laperriere, N. Value of whole brain re-irradiation for brain metastases—Single centre experience. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 19, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, J.A.; Sneed, P.K.; Lamborn, K.R.; Ma, L.; Denduluri, S.; Nakamura, J.L.; Barani, I.J.; McDermott, M.W. Prognostic factors for survival in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery for recurrent brain metastases after prior whole brain radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol Phys. 2012, 83, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.U.; Eierman, W.; Greil, R.; Campone, M.; Kaufman, B.; Steplewski, K.; Lane, S.R.; Zembryki, D.; Rubin, S.D.; Winer, E.P. Randomized phase II study of lapatinib plus capecitabine or lapatinib plus topotecan for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer brain metastases. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2011, 105, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.U.; Pegram, M.; Sahebjam, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Fung, A.; Cheng, A.; Nicholas, A.; Kirschbrown, W.; Kumthekar, P. Pertuzumab Plus High-Dose Trastuzumab in Patients with Progressive Brain Metastases and HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: Primary Analysis of a Phase II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2667–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumthekar, P.; Tang, S.-C.; Brenner, A.J.; Kesari, S.; Piccioni, D.E.; Anders, C.; Carrillo, J.; Chalasani, P.; Kabos, P.; Puhalla, S.; et al. ANG1005, a Brain-Penetrating Peptide-Drug Conjugate, Shows Activity in Patients with Breast Cancer with Leptomeningeal Carcinomatosis and Recurrent Brain Metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2789–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, M.N.; Xu, W.; Wong, R.K.; Lloyd, N.; Laperriere, N.; Sahgal, A.; Rakovitch, E.; Chow, E. Whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD003869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, K.A.; Adkins, C.E.; Nounou, M.I.; Lockman, P.R. Inhibition of VEGF and Angiopoietin-2 to Reduce Brain Metastases of Breast Cancer Burden. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan-Mutlu, A.; Osswald, M.; Liao, Y.; Goemmel, M.; Reck, M.; Miles, D.; Mariani, P.; Gianni, L.; Lutiger, B.; Nendel, V.; et al. Bevacizumab Prevents Brain Metastases Formation in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, C.; Sugimoto, M.; Wakita, D.; Monnai, M.; Ishimaru, C.; Nakamura, R.; Kinoshita, M.; Yorozu, K.; Kurasawa, M.; Kondoh, O.; et al. Bevacizumab suppresses the growth of established non-small-cell lung cancer brain metastases in a hematogenous brain metastasis model. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2020, 37, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, A.; Padmanaban, V.; Aregawi, D.; Glantz, M. VEGF and Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for Prevention of Brain Metastases: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurology 2021, 97, e1484–e1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascha, M.S.; Wang, J.F.; Kumthekar, P.; Sloan, A.E.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Bevacizumab for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer patients with synchronous brain metastases. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, D.; Bent, M.J.v.D. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the treatment of gliomas. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2009, 22, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinot, O.L.; Wick, W.; Mason, W.; Henriksson, R.; Saran, F.; Nishikawa, R.; Carpentier, A.F.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Kavan, P.; Cernea, D.; et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy–temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (Years) | |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (13.5) |

| Median (range) | 54 (27, 73) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Female | 24 (88.9%) |

| Male | 3 (11.1%) |

| Race, no. (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (3.7%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.7%) |

| Black | 3 (11.1%) |

| White | 22 (81.5%) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (14.8%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 23 (85.2%) |

| KPS | |

| Mean (SD) | 83.81 (8.05) |

| Median (range) | 80 (70, 100) |

| Primary Malignancy, no. (%) | |

| Breast | 21 (77.8%) |

| Estrogen Receptor (ER)+ | 9 (42.9%) |

| Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (HER2)+ | 14 (66.7%) |

| Triple Negative (TNBC) | 4 (19.1%) |

| Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Small-Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 (3.7%) |

| Papillary Serous Adenocarcinoma | 1 (3.7%) |

| Concurrent Systemic Treatment | |

| No. (%) | 14 (51.6%) |

| Trastuzumab | 7 (26%) |

| Capecitabine | 5 (19%) |

| Lapatinib | 3 (11%) |

| Abraxane | 3 (11%) |

| Eribulin | 1 (3%) |

| Halaven | 1 (3)%) |

| Kadcyla | 1 (3%) |

| Osimertinib | 1 (3%) |

| Paclitaxel | 1 (3%) |

| Epratuzumab | 1 (3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dixit, K.; Singer, L.; Grimm, S.A.; Lukas, R.V.; Schwartz, M.A.; Rademaker, A.; Zhang, H.; Kocherginsky, M.; Chernet, S.; Sharp, L.; et al. A Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Solid Tumor Brain Metastases That Have Progressed Following Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112133

Dixit K, Singer L, Grimm SA, Lukas RV, Schwartz MA, Rademaker A, Zhang H, Kocherginsky M, Chernet S, Sharp L, et al. A Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Solid Tumor Brain Metastases That Have Progressed Following Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112133

Chicago/Turabian StyleDixit, Karan, Lauren Singer, Sean Aaron Grimm, Rimas V. Lukas, Margaret A. Schwartz, Alfred Rademaker, Hui Zhang, Masha Kocherginsky, Sofia Chernet, Laura Sharp, and et al. 2024. "A Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Solid Tumor Brain Metastases That Have Progressed Following Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112133

APA StyleDixit, K., Singer, L., Grimm, S. A., Lukas, R. V., Schwartz, M. A., Rademaker, A., Zhang, H., Kocherginsky, M., Chernet, S., Sharp, L., Nelson, V., Raizer, J. J., & Kumthekar, P. (2024). A Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Solid Tumor Brain Metastases That Have Progressed Following Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy. Cancers, 16(11), 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112133