Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged over 80 Years Old

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

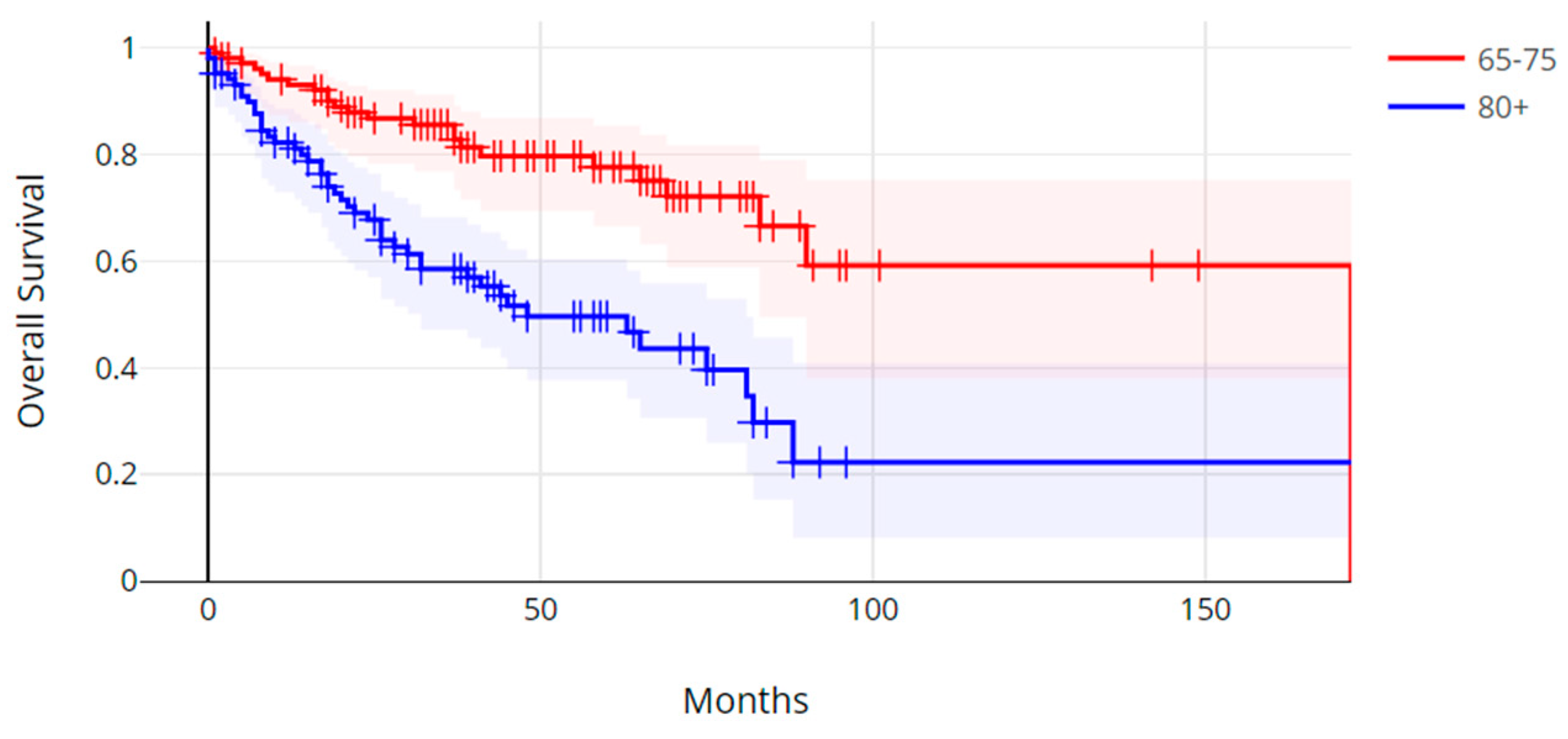

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Adam, M.; Chang, G.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.A.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. Colon Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2024, 22, e240029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelakas, A.; Christodoulou, T.; Kamposioras, K.; Barriuso, J.; Braun, M.; Hasan, J.; Marti, K.; Misra, V.; Mullamitha, S.; Saunders, M.; et al. Is early-onset colorectal cancer an evolving pandemic? Real-world data from a tertiary cancer center. Oncologist 2024, 29, e1680–e1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldvaser, H.; Purim, O.; Kundel, Y.; Shepshelovich, D.; Shochat, T.; Shemesh-Bar, L.; Sulkes, A.; Brenner, B. Colorectal cancer in young patients: Is it a distinct clinical entity? Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 21, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voutsadakis, I.A. Presentation, Molecular Characteristics, Treatment, and Outcomes of Colorectal Cancer in Patients Older than 80 Years Old. Medicina 2023, 59, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kajiwara, Y.; Ueno, H. Essential updates 2022–2023: Surgical and adjuvant therapies for locally advanced colorectal cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2024, 8, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldvaser, H.; Katz Shroitman, N.; Ben-Aharon, I.; Purim, O.; Kundel, Y.; Shepshelovich, D.; Shochat, T.; Sulkes, A.; Brenner, B. Octogenarian patients with colorectal cancer: Characterizing an emerging clinical entity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Voutsadakis, I.A. Clinical tools for chemotherapy toxicity prediction and survival in geriatric cancer patients. J. Chemother. 2018, 30, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habbous, S.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Menjak, I.B.; Forster, K.; Holloway, C.M.B.; Darling, G. The effect of age on the opportunity to receive cancer treatment. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 81, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassen, Y.H.M.; Bastiaannet, E.; van Eycken, E.; Van Damme, N.; Martling, A.; Johansson, R.; Iversen, L.H.; Ingeholm, P.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Liefers, G.J.; et al. Time trends of short-term mortality for octogenarians undergoing a colorectal resection in North Europe. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diers, J.; Baum, P.; Lehmann, K.; Uttinger, K.; Baumann, N.; Pietryga, S.; Hankir, M.; Matthes, N.; Lock, J.F.; Germer, C.T.; et al. Disproportionately high failure to rescue rates after resection for colorectal cancer in the geriatric patient population—A nationwide study. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 4256–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dolin, T.G.; Mikkelsen, M.K.; Jakobsen, H.L.; Vinther, A.; Zerahn, B.; Nielsen, D.L.; Johansen, J.S.; Lund, C.M.; Suetta, C. The prevalence of sarcopenia and cachexia in older patients with localized colorectal cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotake, K.; Asano, M.; Ozawa, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Sugihara, K. Tumour characteristics, treatment patterns and survival of patients aged 80 years or older with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahi, C.J.; Myers, L.J.; Slaven, J.E.; Haggstrom, D.; Pohl, H.; Robertson, D.J.; Imperiale, T.F. Lower endoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence in older individuals. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 718–725.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidelbaugh, J.J. The Adult Well-Male Examination. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 98, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ness, R.M.; Llor, X.; Abbass, M.A.; Bishu, S.; Chen, C.T.; Cooper, G.; Early, D.S.; Friedman, M.; Fudman, D.; Giardiello, F.M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Colorectal Cancer Screening, Version 1.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolo, A.; Rosso, C.; Voutsadakis, I.A. Breast Cancer in Patients 80 Years-Old and Older. Eur. J. Breast Health 2020, 16, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sell, N.M.; Qwaider, Y.Z.; Goldstone, R.N.; Stafford, C.E.; Cauley, C.E.; Francone, T.D.; Ricciardi, R.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Berger, D.L.; Kunitake, H. Octogenarians present with a less aggressive phenotype of colon adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2020, 168, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, S.M.; Shin, J.S. Colorectal Cancer in Octogenarian and Nonagenarian Patients: Clinicopathological Features and Survivals. Ann. Coloproctol. 2020, 36, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høydahl, Ø.; Edna, T.H.; Xanthoulis, A.; Lydersen, S.; Endreseth, B.H. Octogenarian patients with colon cancer—Postoperative morbidity and mortality are the major challenges. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vermeer, N.C.A.; Claassen, Y.H.M.; Derks, M.G.M.; Iversen, L.H.; van Eycken, E.; Guren, M.G.; Mroczkowski, P.; Martling, A.; Johansson, R.; Vandendael, T.; et al. Treatment and Survival of Patients with Colon Cancer Aged 80 Years and Older: A EURECCA International Comparison. Oncologist 2018, 23, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bergquist, J.R.; Thiels, C.A.; Spindler, B.A.; Shubert, C.R.; Hayman, A.V.; Kelley, S.R.; Larson, D.W.; Habermann, E.B.; Pemberton, J.H.; Mathis, K.L. Benefit of Postresection Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer in Octogenarians: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2016, 59, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, T.; de Gramont, A.; Vernerey, D.; Chibaudel, B.; Bonnetain, F.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Scriva, A.; Hickish, T.; Tabernero, J.; Van Laethem, J.L.; et al. Adjuvant Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Oxaliplatin in Stage II to III Colon Cancer: Updated 10-Year Survival and Outcomes According to BRAF Mutation and Mismatch Repair Status of the MOSAIC Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4176–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibutani, M.; Maeda, K.; Kashiwagi, S.; Hirakawa, K.; Ohira, M. Effect of Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Survival of Elderly Patients With Stage III Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 3615–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hurria, A.; Togawa, K.; Mohile, S.G.; Owusu, C.; Klepin, H.D.; Gross, C.P.; Lichtman, S.M.; Gajra, A.; Bhatia, S.; Katheria, V.; et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3457–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reed, M.; Patrick, C.; Quevillon, T.; Walde, N.; Voutsadakis, I.A. Prediction of hospital admissions and grade 3-4 toxicities in cancer patients 70 years old and older receiving chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.; Reed, M.; Walde, N.; Voutsadakis, I.A. An evaluation of the Index4 tool for chemotherapy toxicity prediction in cancer patients older than 70 years old. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loh, K.P.; Liposits, G.; Arora, S.P.; Neuendorff, N.R.; Gomes, F.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Amaral, T.; Mariamidze, E.; Biganzoli, L.; Brain, E.; et al. Adequate assessment yields appropriate care-the role of geriatric assessment and management in older adults with cancer: A position paper from the ESMO/SIOG Cancer in the Elderly Working Group. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012, 487, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giannakis, M.; Mu, X.J.; Shukla, S.A.; Qian, Z.R.; Cohen, O.; Nishihara, R.; Bahl, S.; Cao, Y.; Amin-Mansour, A.; Yamauchi, M.; et al. Genomic Correlates of Immune-Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roelands, J.; Kuppen, P.J.K.; Ahmed, E.I.; Mall, R.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, P.; Monaco, G.; Raynaud, C.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C.; Ferraro, L.; et al. An integrated tumor, immune and microbiome atlas of colon cancer. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Characteristic | All (%) (n = 210) | Group > 80 Years Old (%) (n = 104) | Group 65–75 Years Old (%) (n = 106) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (Range) | 85 (80–95) | 71 (65–75) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 116 (55.2%) | 53 (51.0%) | 63 (59.4%) | 0.21 |

| Female | 94 (44.8%) | 51 (49.0%) | 43 (40.6%) | |

| Family History of Colon Cancer | ||||

| Yes | 44 (21.6%) | 22 (22.4%) | 22 (20.8%) | 0.77 |

| No | 160 (78.4%) | 76 (77.6%) | 84 (79.2%) | |

| N/A | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Family History of Other Cancers | ||||

| Yes | 121 (59.3%) | 52 (53.1%) | 69 (65.1%) | 0.08 |

| No | 83 (40.7%) | 46 (46.9%) | 37 (34.9%) | |

| N/A | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Presentation of Disease | ||||

| Incidental/Screening | 67 (32.4%) | 26 (25.0%) | 41 (39.8%) | 0.10 |

| Anemia/Bleeding | 114 (55.1%) | 64 (61.5%) | 50 (48.5%) | |

| Bowel Changes/Obstruction | 26 (12.5%) | 14 (13.5%) | 12 (11.7%) | |

| N/A | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Location of Tumor | ||||

| Right | 120 (57.4%) | 63 (61.2%) | 57 (53.8%) | 0.48 |

| Left | 34 (16.3%) | 14 (13.6%) | 20 (18.9%) | |

| Rectal/Rectosigmoid | 55 (26.3%) | 26 (25.2%) | 29 (27.3%) | |

| N/A | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | ||||

| I | 40 (21.3%) | 17 (19.5%) | 23 (22.7%) | 0.45 |

| II | 73 (38.8%) | 38 (43.7%) | 35 (34.7%) | |

| III | 75 (39.9%) | 32 (36.8%) | 43 (42.6%) | |

| N/A | 22 | 17 | 5 | |

| Grade of Tumor | ||||

| 1 | 24 (14.2%) | 14 (17.5%) | 10 (11.2%) | 0.37 |

| 2 | 60 (35.5%) | 25 (31.2%) | 35 (39.4%) | |

| 3 | 85 (50.3%) | 41 (51.3%) | 44 (49.4%) | |

| N/A | 41 | 24 | 17 |

| All (%) (n = 210) | Group > 80 Years Old (n = 104) | Group 65–75 Years Old (n = 106) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA | ||||

| ≤4.7 µg/L | 129 (70.5%) | 66 (72.5%) | 63 (68.5%) | 0.55 |

| >4.7 µg/L | 54 (29.5%) | 25 (27.5%) | 29 (31.5%) | |

| N/A | 27 | 13 | 14 | |

| LDH | ||||

| ≤210 U/L | 181 (90.0%) | 90 (90.9%) | 91 (89.2%) | 0.69 |

| >210 U/L | 20 (10.0%) | 9 (9.1%) | 11 (10.8%) | |

| N/A | 9 | 5 | 4 | |

| Albumin | ||||

| <35 g/L | 59 (29.2%) | 33 (33.0%) | 26 (25.5%) | 0.24 |

| ≥35 g/L | 143 (70.8%) | 67 (67.0%) | 76 (74.5%) | |

| N/A | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| Platelets | ||||

| ≤400 × 109/L | 185 (88.9%) | 93 (90.3%) | 92 (87.6%) | 0.54 |

| >400 × 109/L | 23 (11.1%) | 10 (9.7%) | 13 (12.4%) | |

| N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Glucose | ||||

| ≤7 mmol/L | 87 (52.4%) | 45 (97.6%) | 42 (50.0%) | 0.53 |

| >7 mmol/L | 79 (47.6%) | 37 (2.4%) | 42 (50.0%) | |

| N/A | 44 | 22 | 22 | |

| Creatinine | ||||

| ≤130 µmol/L | 189 (90.4%) | 88 (84.6%) | 101 (96.2%) | 0.004 |

| >130 µmol/L | 20 (9.6%) | 16 (15.4%) | 4 (3.8%) | |

| N/A | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Treatment | All (%) | Group > 80 Years Old (%) | Group 65–75 Years Old (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (rectosigmoid/rectal) | ||||

| Yes | 22 (40.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 17 (58.6%) | 0.002 |

| No | 33 (60.0%) | 21 (80.7%) | 12 (41.4%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (stage II) | ||||

| Yes | 17 (23.3%) | 3 (7.9%) | 14 (40.0%) | 0.002 |

| No | 56 (76.7%) | 35 (92.1%) | 21 (60.0%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (stage III) | ||||

| Yes | 58 (77.3%) | 22 (68.7%) | 36 (83.7%) | 0.13 |

| No | 17 (22.7%) | 10 (31.3%) | 7 (16.3%) | |

| Type of adjuvant chemotherapy (stage II and III) | ||||

| Capecitabine | 21 (28.0%) | 15 (60.0%) | 6 (12.0%) | 0.00002 |

| FOLFOX or CAPOX | 48 (64.0%) | 7 (28.0%) | 41 (82.0%) | |

| FOLFIRI/Bevacizumab | 6 (8.0%) | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy dose reduction | ||||

| Yes | 24 (32.0%) | 19 (76.0%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0.0001 |

| No | 51 (68.0%) | 6 (24.0%) | 45 (90.0%) | |

| Neoadjuvant/adjuvant radiation (rectosigmoid/rectal) | ||||

| Yes | 28 (50.9%) | 9 (34.6%) | 19 (65.5%) | 0.02 |

| No | 27 (49.1%) | 17 (65.4%) | 10 (34.5%) | |

| Palliative radiation | ||||

| Yes | 13 (6.2%) | 11 (10.6%) | 2 (1.9%) | 0.01 |

| No | 197 (93.8%) | 93 (89.4%) | 104 (98.1%) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Yes | 188 (89.5%) | 87 (83.7%) | 101 (95.3%) | 0.006 |

| No | 22 (10.5%) | 17 (16.3%) | 5 (4.7%) |

| Adverse Effect | All (%) (n = 91) | Group > 80 Years Old (%) (n = 32) | Group 65–75 Years Old (%) (n = 59) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | ||||

| Yes | 19 (20.9%) | 7 (21.9%) | 12 (20.3%) | 1.00 |

| No | 72 (79.1%) | 25 (78.1%) | 47 (79.7%) | |

| Neutropenia (grade 4) | ||||

| Yes | 4 (4.4%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (6.8%) | 0.3 |

| No | 87 (95.6%) | 32 (100.00%) | 55 (93.2%) | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | ||||

| Yes | 25 (27.5%) | 3 (9.4%) | 22 (37.3%) | 0.01 |

| No | 66 (72.5%) | 29 (90.6%) | 37 (62.7%) | |

| Hand–foot syndrome/skin changes | ||||

| Yes | 19 (20.9%) | 10 (31.3%) | 9 (15.2%) | 0.10 |

| No | 72 (79.1%) | 22 (68.7%) | 50 (84.8%) | |

| Bowel changes (diarrhea, constipation) | ||||

| Yes | 34 (37.4%) | 12 (37.5%) | 22 (37.3%) | 1.00 |

| No | 57 (62.6%) | 20 (62.5%) | 37 (62.7%) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | ||||

| Yes | 18 (19.8%) | 5 (15.6%) | 13 (22.0%) | 0.59 |

| No | 73 (80.2%) | 27 (84.4%) | 46 (78.0%) | |

| Mucositis | ||||

| Yes | 7 (7.7%) | 3 (9.4%) | 4 (6.8%) | 0.69 |

| No | 84 (92.3%) | 29 (90.6%) | 55 (93.2%) | |

| Other (dehydration, vision changes, bleeding, dizziness) | ||||

| Yes | 15 (16.5%) | 9 (28.1%) | 6 (10.2%) | 0.04 |

| No | 76 (83.5%) | 23 (71.9%) | 53 (89.8%) |

| Comorbidities | All (%) (n = 210) | Group > 80 Years Old (%) (n = 104) | Group 65–75 Years Old (%) (n = 106) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity (n = 210) | ||||

| BMI > 30 | 79 (37.6%) | 30 (28.8%) | 49 (46.2%) | 0.01 |

| BMI ≤ 30 | 131 (62.4%) | 74 (71.2%) | 57 (53.8) | |

| Diabetes (n = 209) | ||||

| Yes | 67 (31.9%) | 36 (34.6%) | 31 (29.2%) | 0.43 |

| No | 142 (67.6%) | 68 (65.4%) | 74 (69.8%) | |

| Hypertension (n = 209) | ||||

| Yes | 158 (75.2%) | 87 (83.7%) | 71 (66.9%) | 0.007 |

| No | 51 (24.8%) | 17 (16.3%) | 34 (32.1%) | |

| Cardiovascular/neurovascular disease (n = 209) | ||||

| Yes | 99 (47.1%) | 68 (65.4%) | 31 (29.2%) | 0.0001 |

| No | 110 (52.4%) | 36 (34.6%) | 74 (69.8%) | |

| Dyslipidemia (n = 209) | ||||

| Yes | 108 (51.4%) | 62 (59.6%) | 46 (43.4%) | 0.02 |

| No | 101 (48.6%) | 42 (40.4%) | 59 (55.7%) |

| Characteristic | Comparison | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Family history of other cancers besides colorectal cancer | Trend of higher prevalence in younger group | 0.08 |

| Presentation of disease | Trend of more frequent presentation with anemia or bleeding in older group | 0.1 |

| Laboratory evaluation | ||

| Creatinine | Older group more frequently (15.4% of cases) had elevated values than younger group (3.8% of patients) | 0.004 |

| Treatments | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with rectal/rectosigmoid cancer | More commonly administered in younger group (58.6% of patients) than in older patients (19.2%) | 0.002 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | More frequent use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II cancers in younger group (40% versus 7.9% of older patients), but no difference in use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients | 0.002 |

| Type of adjuvant chemotherapy | More frequent use of adjuvant capecitabine monotherapy in older group (60% versus 12% in younger group) | 0.00002 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy dose reduction | More frequently performed in older group (76% versus 10% in younger group) | 0.0001 |

| Neoadjuvant/adjuvant radiation in patients with rectal/rectosigmoid cancer | More frequently given in younger patients (65.5% of patients versus 34.6% of patients in older group) | 0.02 |

| Surgery | Fewer patients in older age group were treated surgically (83.7% versus 95.3% in younger group) | 0.006 |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | More frequent in younger patients (37.3%) than in older patients (9.4%), consistent with more frequent use of oxaliplatin in this group | 0.01 |

| Hand–foot syndrome | Trend for higher incidence in older group (31.3% versus 15.2% of patients in younger group) | 0.10 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Obesity | Higher prevalence in younger group (46.2%) than in older patients (28.8%) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension, cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia | More prevalent in younger patients | 0.007, 0.0001, 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeo, M.R.; Voutsadakis, I.A. Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged over 80 Years Old. Cancers 2025, 17, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020247

Yeo MR, Voutsadakis IA. Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged over 80 Years Old. Cancers. 2025; 17(2):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020247

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeo, Melissa R., and Ioannis A. Voutsadakis. 2025. "Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged over 80 Years Old" Cancers 17, no. 2: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020247

APA StyleYeo, M. R., & Voutsadakis, I. A. (2025). Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged over 80 Years Old. Cancers, 17(2), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020247