Proton Beam Therapy and the AYA Sarcoma Patient Journey: Highlighting Needs from Diagnosis to Survivorship

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Diagnosis and Access to Expert Care

3.2. Proton Beam Therapy (PBT) in AYA Patients

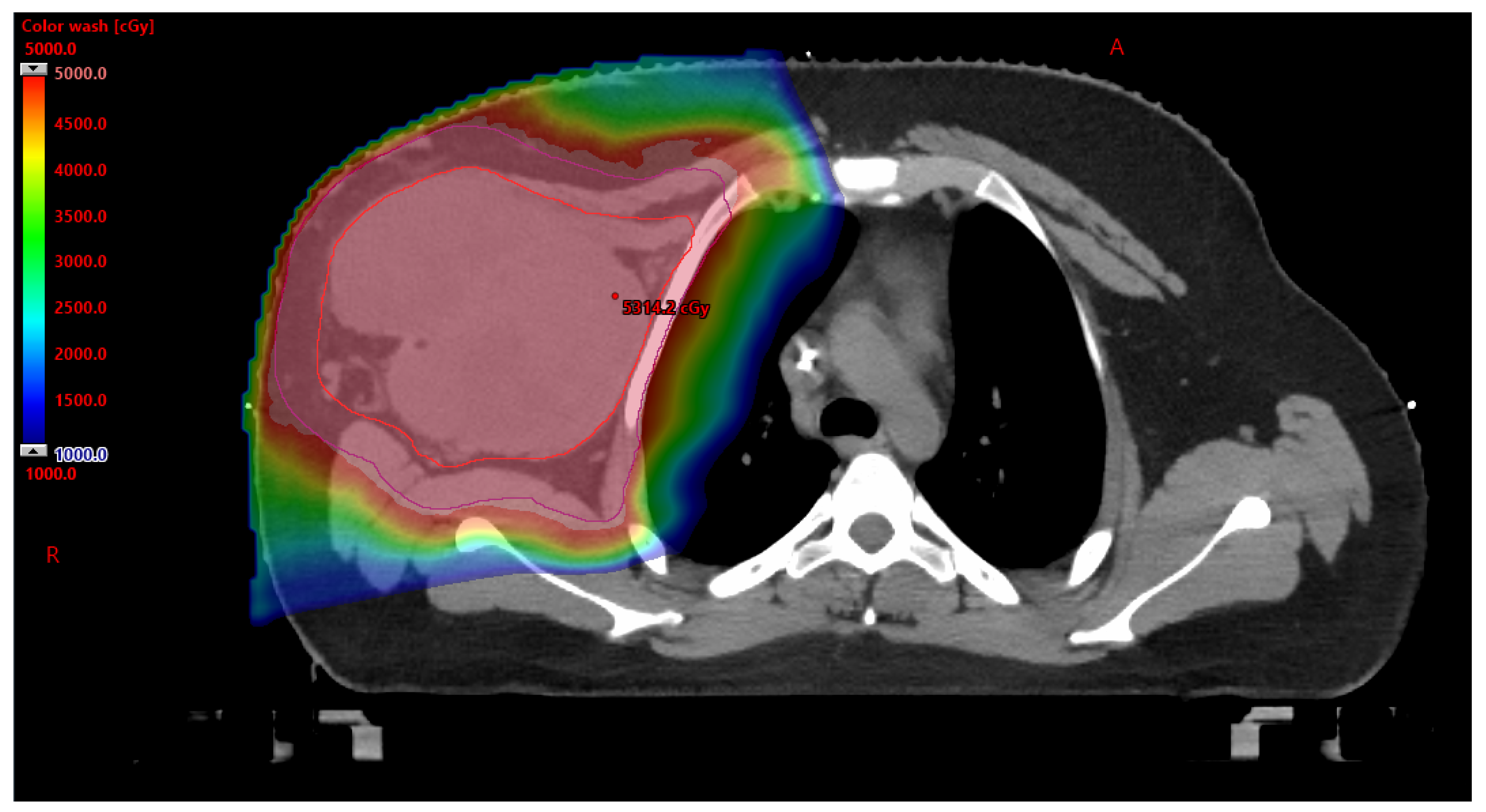

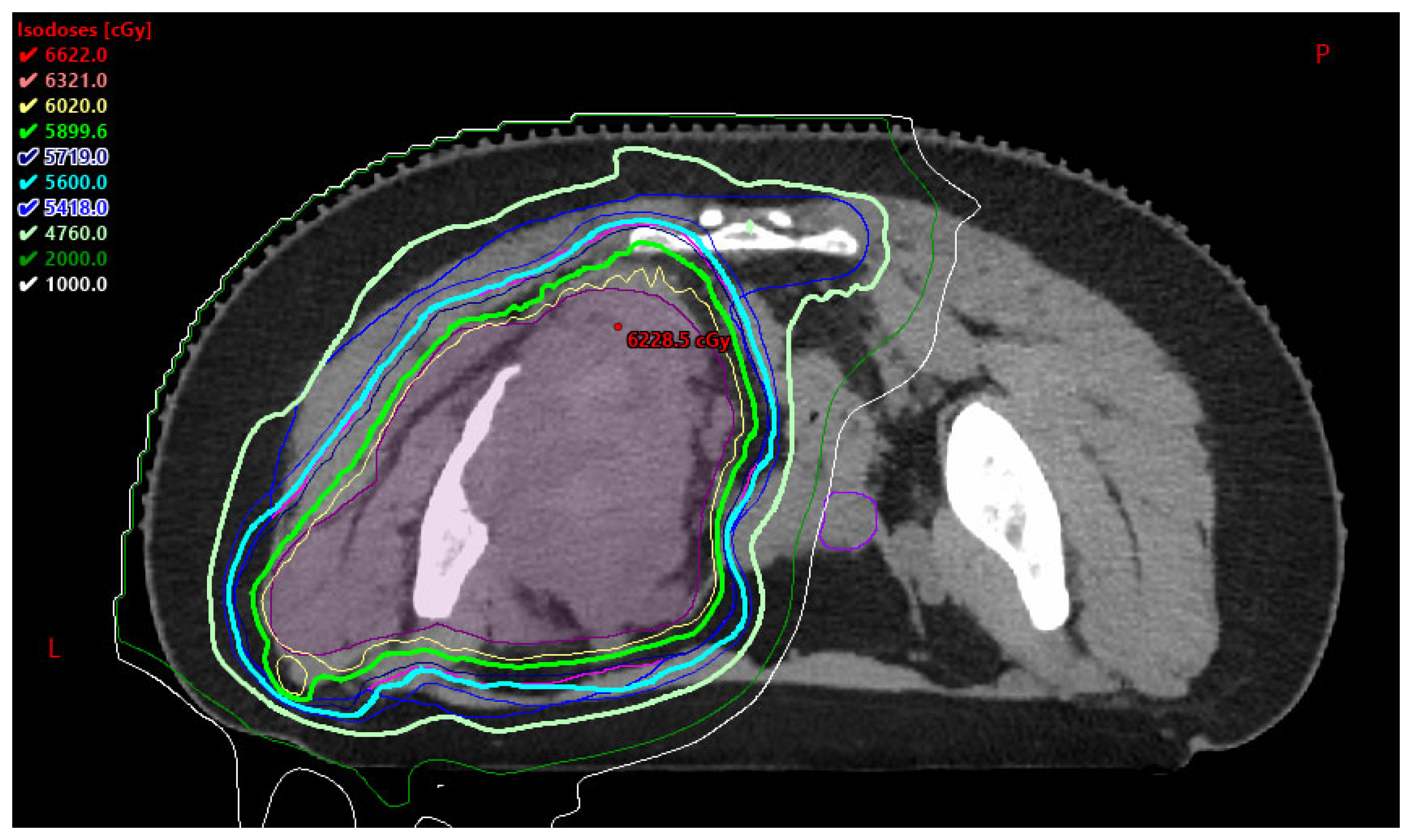

3.2.1. Benefits to PBT

3.2.2. Barriers to PBT

3.3. Developmental and Psychosocial Considerations in AYA Care

3.3.1. Developmental Milestones of an AYA Patient

3.3.2. Fertility Risk and Preservation

- Cancer patients should be evaluated and counseled regarding reproductive risks at diagnosis and during survivorship.

- Patients interested in FP should be referred to a reproductive specialist.

- FP approaches should be discussed before therapy is initiated:

- ○

- Males: sperm cryopreservation.

- ○

- Females: embryo, oocyte, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC), ovarian transposition, and conservative gynecological surgery.

- For patients requiring urgent oncology therapy, GnRH may be offered for menstrual suppression.

- Advocate for comprehensive FP services coverage and support access to benefits [25].

3.3.3. Sexual Health

3.3.4. Long-Term Financial Burden

3.3.5. Palliative Care and Goals of Care

3.3.6. Survivorship

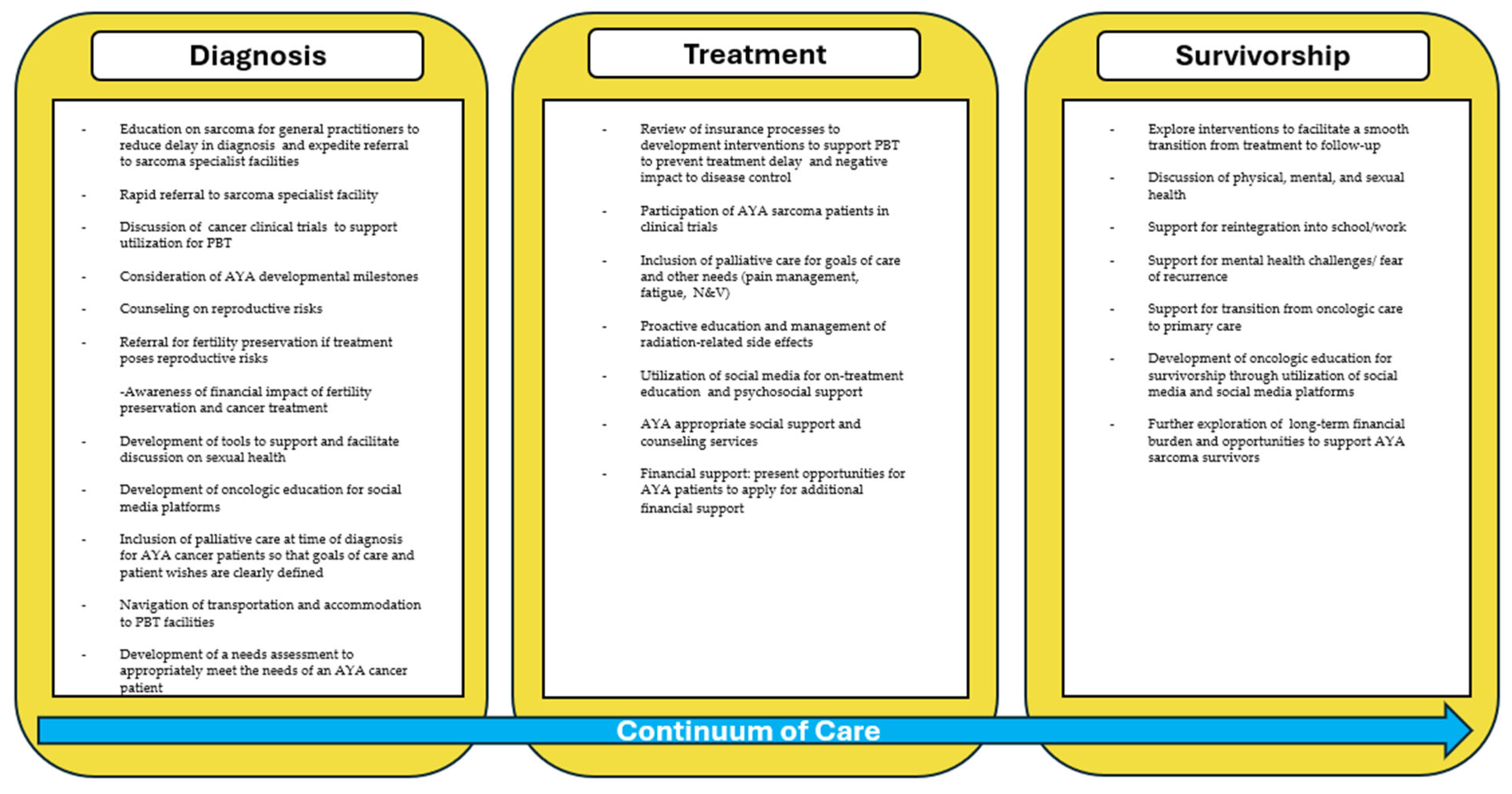

3.4. Future Directions for the Support of AYA Sarcoma Patients

3.4.1. Role of Social Media and Cancer Care Information

3.4.2. Development of an AYA-Specific Program and Future Opportunities

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AYA | Adolescent Young Adult |

| PBT | Proton beam therapy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| CCC | Comprehensive Cancer Center |

| SPAGN | Sarcoma Patient Advocacy Global Network |

| CCT | Cancer clinical trials |

| IMRT | Intensity modulated radiation therapy |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| FP | Fertility Preservation |

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian hormone |

| GRT | Gamma-ray radiation therapy |

| SOBOP | Spread-out Bragg peak |

| YA | Young adults |

| SHO | Sexual health outcomes |

| GOC | Goals of care |

| RT | Radiation therapy |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| CCMB | CancerCare Manitoba |

| CPG | Clinical Practice Guidelines |

| MTB | Multidisciplinary tumor boards |

| NA-SB | Needs Assessment and Service Bridge |

References

- Miller, K.D.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.; Keegan, T.H.; Hipp, H.S.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Lao, S.; Liang, W.; He, J. Global cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults: Population based study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabbe, C.; Coenraadts, E.S.; van Houdt, W.J.; van de Sande, M.A.J.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; de Haan, J.J.; Nin, J.W.M.; Verhoef, C.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Husson, O. Impaired social functioning in adolescent and young adult sarcoma survivors: Prevalence and risk factors. Cancer 2023, 129, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (22 January 2025). Sarcoma. Mayo Clinic. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sarcoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20351048 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, F. Radiation Therapy in Adult Soft Tissue Sarcoma—Current Knowledge and Future Directions: A Review and Expert Opinion. Cancers 2020, 12, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, R.; Reinke, D.; van Oortmerssen, G.; Gonzato, O.; Ott, G.; Raut, C.P.; Guadagnolo, B.A.; Haas, R.L.M.; Trent, J.; Jones, R.; et al. What Is a Sarcoma ‘Specialist Center’? Multidisciplinary Research Finds an Answer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessim, C.; Tzanis, D. Is it time for a change in the model of care for AYA patients with soft tissue sarcoma? How to improve outcomes for patients aged 15-25 using a mixed pediatric-adult cancer care model in expert sarcoma centers. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 1201–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossum, C.C.; Breen, W.G.; Sun, P.Y.; Retzlaff, A.A.; Okuno, S.H. Assessment of Familiarity With Work-up Guidelines for Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcoma Among Primary Care Practitioners in Minnesota. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulaxouzidis, G.; Schwarzkopf, E.; Bannasch, H.; Stark, G.B. Is revisional surgery mandatory when an unexpected sarcoma diagnosis is made following primary surgery? World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannini, S.; Penel, N.; Bompas, E.; Willaume, T.; Kurtz, J.E.; Gantzer, J. Shortening the Time Interval for the Referral of Patients With Soft Tissue Sarcoma to Expert Centers Using Mobile Health: Retrospective Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e40718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarcoma Alliance. Support for Your Journey with Sarcoma. Available online: https://sarcomaalliance.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- National Association for Proton Therapy. Available online: https://proton-therapy.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Bishop, A.J.; Livingston, J.A.; Ning, M.S.; Valdez, I.D.; Wages, C.A.; McAleer, M.F.; Paulino, A.C.; Grosshans, D.R.; Woodhouse, K.D.; Tao, R.; et al. Young Adult Populations Face Yet Another Barrier to Care With Insurers: Limited Access to Proton Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uezono, H.; Indelicato, D.J.; Rotondo, R.L.; Mailhot Vega, R.B.; Bradfield, S.M.; Morris, C.G.; Bradley, J.A. Treatment Outcomes After Proton Therapy for Ewing Sarcoma of the Pelvis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 107, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharod, S.M.; Indelicato, D.J.; Rotondo, R.L.; Mailhot Vega, R.B.; Uezono, H.; Morris, C.G.; Bradfield, S.; Sandler, E.S.; Bradley, J.A. Outcomes following proton therapy for Ewing sarcoma of the cranium and skull base. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEER. Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAS)—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Alliance for Proton Therapy Access. Cancer Care Denied: The Broken State of Patient Access to Proton Therapy. Available online: https://www.heartandsoul.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Cancer-Care-Denied-Report.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Gupta, A.; Khan, A.J.; Goyal, S.; Millevoi, R.; Elsebai, N.; Jabbour, S.K.; Yue, N.J.; Haffty, B.G.; Parikh, R.R. Insurance Approval for Proton Beam Therapy and its Impact on Delays in Treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siembida, E.J.; Loomans-Kropp, H.A.; Trivedi, N.; O’Mara, A.; Sung, L.; Tami-Maury, I.; Freyer, D.R.; Roth, M. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: Identifying opportunities for intervention. Cancer 2020, 126, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, N.; Saha, A.; Avutu, V.; Monga, V.; Freyer, D.R.; Roth, M. Shared barriers and facilitators to enrollment of adolescents and young adults on cancer clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzep, N.; Roth, M. Psychosocial Distress Due to Interference of Normal Developmental Milestones in AYAs with Cancer. Children 2022, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.P.; Kim, S.Y.; Gondi, V.; Pankuch, M.; Wagner, S.; Grover, A.; Luan, Y.; Woodruff, T.K. Proton Radiotherapy to Preserve Fertility and Endocrine Function: A Translational Investigation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.I.; Lacchetti, C.; Letourneau, J.; Partridge, A.H.; Qamar, R.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Smith, J.F.; Tesch, M.; Wallace, W.H.; et al. Fertility Preservation in People With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1488–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsman, J.M.; Yanez, B.; Snyder, M.A.; Avina, A.R.; Clayman, M.L.; Smith, K.N.; Purnell, K.; Victorson, D. Attitudes and practices about fertility preservation discussions among young adults with cancer treated at a comprehensive cancer center: Patient and oncologist perspectives. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5945–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance for Fertility Preservation. Paying for Treatments. Available online: https://www.allianceforfertilitypreservation.org/expenses/cost-of-treatment/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Arc Fertility. Understanding the Cost of IVF in 2024. Available online: https://www.arcfertility.com/patient-resources/understanding-the-cost-of-ivf/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Jackson Levin, N.; Tan, C.Y.; Stelmak, D.; Iannarino, N.T.; Zhang, A.; Ellman, E.; Herrel, L.A.; Walling, E.B.; Moravek, M.B.; Chugh, R.; et al. Banking on Fertility Preservation: Financial Concern for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients Considering Oncofertility Services. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sexual Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Gunderson, A.; Yun, M.; Westlake, B.; Hardacre, M.; Manguso, N.; Gingrich, A.A. Survivorship Considerations and Management in the Adolescent and Young Adult Sarcoma Population: A Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettergren, L.; Kent, E.E.; Mitchell, S.A.; Zebrack, B.; Lynch, C.F.; Rubenstein, M.B.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Wu, X.C.; Parsons, H.M.; Smith, A.W.; et al. Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: The AYA HOPE study. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquati, C.; Zebrack, B.J.; Faul, A.C.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Block, R.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Freyer, D.R.; Cole, S. Sexual functioning among young adult cancer patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Cancer 2018, 124, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oveisi, N.; Cheng, V.; Brotto, L.A.; Peacock, S.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Hanley, G.; Gill, S.; Rayar, M.; Srikanthan, A.; Ellis, U.; et al. Sexual health outcomes among adolescent and young adult cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkad087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopfe, J.; Marsh, R.; Frederick, N.N.; Klosky, J.L.; Chow, E.J.; Dorsey Holliman, B.; Peterson, P.N. Adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors’ preferences for screening and education of sexual function. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e29229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Meltzer, K.J.; Dunker, A.M.; Hall, B.C. Point-of-care assessment of sexual concerns among young adult oncology active patients and survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.K.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Parsons, H.M.; Yabroff, K.R.; Davies, S.J. Cost of Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States: Results of the 2021 Report by Deloitte Access Economics, Commissioned by Teen Cancer America. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3260–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Price Estimates. Mayo Clinic. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/billing-insurance/price-estimates (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Altice, C.K.; Banegas, M.P.; Tucker-Seeley, R.D.; Yabroff, K.R. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 109, djw205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.S.; Benedict, C.; Friedman, D.N.; Watson, S.E.; Anglade, E.; Zeitler, M.S.; Chino, F.; Thom, B. Do discussions of financial burdens decrease long-term financial toxicity in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors? Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, M.S.; Watson, S.E.; Macpherson, C.F.; Novak, K.A.; Johnson, R.H. The cost of cancer: A retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, B.; Friedman, D.N.; Aviki, E.M.; Benedict, C.; Watson, S.E.; Zeitler, M.S.; Chino, F. The long-term financial experiences of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/palliative-care (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Johnston, E.E.; Rosenberg, A.R. Palliative Care in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.M.; Ferraro, K.; Durfee, J.; Indovina, K.A. Social Determinants of Health Impacting the Experience of Young Adults With Cancer at a Single Community Urban Hospital: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Patient Exp. 2024, 11, 23743735241255450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastropolo, R.; Cernik, C.; Uno, H.; Fisher, L.; Xu, L.; Laurent, C.A.; Cannizzaro, N.; Munneke, J.; Cooper, R.M.; Lakin, J.R.; et al. Evolution in Documented Goals of Care at End of Life for Adolescents and Younger Adults With Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2450489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bonnet, J.; Cernik, C.; Uno, H.; Xu, L.; Laurent, C.A.; Fisher, L.; Cannizzaro, N.; Munneke, J.; Cooper, R.M.; Lakin, J.R.; et al. Timing and Outcomes of Palliative Care Integration Into Care of Adolescents and Young Adults With Advanced Cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, OP2400907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, S.H.M.; Vlooswijk, C.; Bijlsma, R.M.; Kaal, S.E.J.; Kerst, J.M.; Tromp, J.M.; Bos, M.E.M.M.; van der Hulle, T.; Lalisang, R.I.; Nuver, J.; et al. Health-related conditions among long-term cancer survivors diagnosed in adolescence and young adulthood (AYA): Results of the SURVAYA study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, S.H.M.; Vlooswijk, C.; Bijlsma, R.M.; Kaal, S.E.J.; Kerst, J.M.; Tromp, J.M.; Bos, M.E.M.M.; van der Hulle, T.; Lalisang, R.I.; Nuver, J.; et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors compared to a matched normative population: Results of the SURVAYA study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, M.A.; Drake, E.K.; Pemmaraju, N.; Wood, W.A. Social Media and the Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Patient with Cancer. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2016, 11, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, K.L.; Reeve, B.B.; Salsman, J.M.; Siembida, E.J.; Smith, G.L.; Swartz, M.C.; Lee, K.L.; Afridi, F.; Andring, L.M.; Bishop, A.J.; et al. Association of Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life With Physician-Reported Toxicities in Adolescents and Young Adults Receiving Radiation Therapy for Cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydeman, J.A.; Uwazurike, O.C.; Adeyemi, E.I.; Beaupin, L.K. Survivorship needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A concept mapping analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Fogarasi, M.; Lustberg, M.B.; Nekhlyudov, L. Perspectives of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: Review of community-based discussion boards. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 16, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, E.; Martin, S.R.; Seidman, L.C.; Zeltzer, L.K.; Cousineau, T.M.; Payne, L.A.; Knoll, M.; Weiman, M.; Federman, N.C. The Role of Social Media in Providing Support from Friends for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Patients and Survivors of Sarcoma: Perspectives of AYA, Parents, and Providers. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.; Bender, J.; Hueniken, K.; Kassirian, S.; Mitchell, L.; Aggarwal, R.; Paulo, C.; Smith, E.C.; Geist, I.; Balaratnam, K.; et al. Age differences in patterns and confidence of using internet and social media for cancer-care among cancer survivors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E.; Rost, M.; Gumy-Pause, F.; Diesch, T.; Espelli, V.; Elger, B.S. Moving Beyond the Friend-Foe Myth: A Scoping Review of the Use of Social Media in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, I.; Oberoi, S. Developing an Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program in a Medium-Sized Canadian Centre: Lessons Learned. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2420–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, E.R.; Lux, L.; Swift, C.; Matson, M.; Kleissler, D.; Stein, J.; Childers, J.; Salsman, J.M.; Smitherman, A.B. The Adolescent and Young Adult Needs Assessment & Service Bridge (NA-SB): A single-arm feasibility pilot study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2024, 42, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harris, M.M.; Ahmed, S.K. Proton Beam Therapy and the AYA Sarcoma Patient Journey: Highlighting Needs from Diagnosis to Survivorship. Cancers 2025, 17, 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213402

Harris MM, Ahmed SK. Proton Beam Therapy and the AYA Sarcoma Patient Journey: Highlighting Needs from Diagnosis to Survivorship. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213402

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarris, Margaret M., and Safia K. Ahmed. 2025. "Proton Beam Therapy and the AYA Sarcoma Patient Journey: Highlighting Needs from Diagnosis to Survivorship" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213402

APA StyleHarris, M. M., & Ahmed, S. K. (2025). Proton Beam Therapy and the AYA Sarcoma Patient Journey: Highlighting Needs from Diagnosis to Survivorship. Cancers, 17(21), 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213402