Abstract

This research investigates the aesthetic evaluation of AI-generated neoplasticist artworks, exploring how well artificial intelligence systems, specifically Midjourney, replicate the core principles of neoplasticism, such as geometric forms, balance, and color harmony. The background of this study stems from ongoing debates about the legitimacy of AI-generated art and how these systems engage with established artistic movements. The purpose of the research is to assess whether AI can produce artworks that meet aesthetic standards comparable to human-created works. The research utilized Monroe C. Beardsley’s aesthetic emotion criteria and Noël Carroll’s aesthetic experience criteria as a framework for evaluating the artworks. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify key compositional elements in AI-generated neoplasticist works. The findings revealed that AI systems excelled in areas such as unity, color diversity, and overall artistic appeal but showed limitations in handling monochromatic elements. The implications of this research suggest that while AI can produce high-quality art, further refinement is needed for more subtle aspects of design. This study contributes to understanding the potential of AI as a tool in the creative process, offering insights for both artists and AI developers.

1. Introduction

After the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we must realize that the application of artificial intelligence to art is not only interesting but also controversial [1]. It is also interesting at the times, but for once, in an academic way, especially an engineering approach, the study of its value as well as its definition, is inevitable. Indeed, a conventional movement has begun to engage in the fields of music, literature, video, and visual arts, where artificial intelligence valued human creativity and originality [2]. The academic perspective, which divided traditional engineering, humanities, and art studies, has become skeptical that machines can create art creations that have been relegated to the unique human realm. Art, which has embodied human emotions, emotions, intuitions, and experiences in a unique way of expression, has been regarded as the result of unique human effort and expression.

This traditional and conservative perspective on art needs to discuss the evaluation of the artistic value of AI creations that are contemporary and not new for the future, in line with the engineering, mathematical, and technological advances of artificial intelligence that have enabled production and creativity [3]. In this study, it is a field of visual art that can be created by artificial intelligence that can be applied with qualitative analysis such as inspiration as well as quantitative criteria according to the existing artistic trend by utilizing algorithms. This study aims to serve as a cornerstone for the prosperity of research on the artistic value assessment of visual creations created by artificial intelligence by exploring the quantitative and constitutive characteristics and aesthetic characteristics of the neoplasticism art trend.

The use of engineering technology such as artificial intelligence in creative artistic activities is nothing new. With the help of computer graphics technology and hardware and software technology in mathematical operations of data analysis, artists and those looking to engage in such engineering artistic activities have been exploring new creations for decades [4]. Program Using machine learning as an example of the challenge of automated creations, Harold Cohen’s “AARON” is the first artificial intelligence (AI) program for creating artworks. Cohen (1928–2016) left behind his work as an established artist in London and conceived the software at the University of California, San Diego in the late 1960s, giving it the name AARON in the early 1970s [5,6]. After the 1990s, the second winter of AI, today’s highly sophisticated generative AI is developing algorithmic levels that can create higher-quality artworks. In particular, Midjourney, DALL-E 3, Stable Diffusion, Google’s DeepDream, and Microsoft’s Bing Image Creator create visual content that can match human creation [7,8]. With the development of these period technologies, interest in valuing artificial intelligence-generated creations for their art potential continues to grow [9].

One area of technology in AI systems that is both interesting and special is that they understand the inspiration embedded in historical art movements or trends and can replicate it and apply it [10,11]. Neoplasticism, a movement founded by Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg in the early 20th century, is one such movement that has garnered attention. Neoplasticism, also known as De Stijl, is characterized by its use of geometric shapes to have a theoretical background to geometrically realize all abstract expressions based on basic poly chromatic and achromatic colors on surfaces divided by vertical and horizontal lines, primarily squares and rectangles which are the configuration based on vertical and horizontal straight lines, and a limited color palette consisting of the things such as the primary colors of red, yellow, and blue and the achromatic colors of black, gray, and white [12].

The movement sought to express harmony and order through abstract, non-representational forms. Given its emphasis on formal elements such as shape and color, neoplasticism provides a clear framework that can be translated into the rule-based logic of AI algorithms [13,14]. There are still some divisions or differences in the continuing growth of generative AI art. Existing research has focused on the technical aspects of AI systems, such as how they generate new outcomes with algorithms that learn art tendencies, but research on whether these AI systems capture the corresponding aesthetic compositional principles in certain art trends or tendencies, such as neoclassicism, is relatively scarce.

Most research so far has evaluated AI-generated art in terms of its ability to imitate and learn surface features of art styles, such as color structures or brush strokes [15]. Some researchers have only explored the creative abilities of machine learning with AI systems in abstract and contemporary art, and there has still been insufficient artistic valuation for high-level interpretations, such as the expressionism of the abstract art trend [16,17]. Neoplasticism, however, is a movement that is highly structured and rule-based, strictly adhering to geometric shapes and color harmonies with a composition of red, yellow, and blue on a surface divided by a vertical line and a horizontal line, and an achromatic black, gray, and white. This makes it an ideal research candidate for assessing how well AI systems can combine with formal aesthetic principles. However, few empirical studies have investigated how effectively AI can generate works consistent with the neoclassical trend of balance, proportion, and order. Therefore, this particularity is noteworthy as a remarkable study, as the neoclassical structured approach theoretically fits well into computational interpretation.

Research to bridge this gap is important for a few reasons. First, as AI continues to play a big role in the field of visual arts, understanding how it relates to aesthetic principles with systematic analysis can help artists, curators, and scholars to well evaluate the artistic value of AI-generated works. Neoplasticism, through clear formal rules, can provide opportunities for AI to go beyond simple pattern replication, such as machine learning, to understand deeper structures [18]. In addition, it can gain insights into AI, which creates neoplasticist artworks with characteristics of creativity and artistic expression. If AI can successfully generate art that complies with the principle of neoplasticism, it may suggest that the boundary between human and machine creativity is more porous than previously thought [19]. Second, exploring AI-generated neoclassical art can have practical implications for the development of creative AI systems. It is important to understand both the strengths and limitations of these systems as AI-generated art becomes more integrated into commercial and creative industries. Focusing on structured analysis, such as neoclassicism, this study can highlight areas where AI excels in producing consistent and aesthetically attractive works and areas that require further development. Understanding this marginal perspective can help advance AI models in the future, especially in terms of their ability to participate in more complex art traditions [20].

This study proposes a comprehensive evaluation of AI-generated neoplasticist artworks using established frameworks from art theory which is Good Artwork Calculation Equation in Formula. Specifically, it applies Monroe C. Beardsley’s aesthetic emotion criteria and Noël Carroll’s aesthetic experience criteria to assess the aesthetic value of these works. Logistic regression analysis was used in this study to see how well machine learning was performed by capturing the formal elements of neoplasticism, including vertical and horizontal geometric shapes and spatial balance, and the color harmony of primary and achromatic color as a method of analyzing compositional methods.

In particular, there is a part that attempts to identify the difference between the neoplasticist artworks created by artificial intelligence used in this study and the neoplasticist artworks created by humans. This study contributes to literature research by providing the basis for a detailed examination of artificial intelligence capabilities for art trends with specific structured forms and elements. Unlike previous studies that focused on the technical capabilities of AI systems, this study highlights the aesthetic and compositional dimensions of AI-generated art, providing insight into how well these AI-driven visual creation systems replicate the formal principles of neoplasticism and can even create the emotional parts of humans through machine learning.

The results of this study have significant implications for both the field of creative generative AI system technology and the art field, which has maintained the traditional trend. As an insight into the research results, AI systems can create attractive creations through aesthetic categories and machine learning, but it suggests that there is still a limit to realizing creative artistic values through machine learning by perfectly capturing the deep compositional logic defined by certain art trends. This study provides a framework background and theory to evaluate the artistic value of AI-generated creations in a more rigorous and systematic way by suggesting a new direction and path for interdisciplinary research between artificial intelligence, art history, and aesthetic theory [21].

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Paradigm Shift in the Perception of Artistic Merit

When the medium of photography first emerged, it was not readily accepted by established artists as a legitimate art [22,23,24,25]. However, photography has since gained widespread recognition as an art form, and its artistic domain has expanded considerably, diversifying and broadening its scope [26]. In less than a century, photography has become integral to nearly every aspect of modern life [27,28,29]. Today, most individuals carry cameras on their mobile devices, capturing photographs daily. Photographic imagery permeates electronic devices, print media, and advertising, making photography omnipresent. This ubiquity has made it increasingly difficult to define what photography is and whether it still qualifies as a legitimate art form. Photography serves multiple purposes and encompasses various dimensions; it can convey narratives, capture fleeting moments, document, and even be elevated to the status of art [30,31]. Beyond its technical applications, photography is also a deeply social and creative medium, with highly personalized and varied uses [32].

Photography’s evolution from a photochemical technique mediated by the mechanical apparatus of the camera is distinct from other art forms like painting, which traditionally required significant manual labor. The camera’s technical ability to capture subjects with heightened realism afforded photography a unique historical position, straddling both artistic expression and factual documentation [33]. This versatility has allowed photography to explore a wide range of creative possibilities. Initially invented in the 1830s, photography was not recognized as art because of its mechanical production, rather than the direct involvement of the artist’s hand [34]. It was only in the 1910s that photography began to be accepted as an artistic medium. Paradoxically, artists eventually embraced the mechanical nature of photography, utilizing it to expand the medium’s artistic potential through diverse techniques and approaches.

Technically, photography can be divided into the capture of the subject and the subsequent processes of developing and printing the image [35,36,37]. Throughout this evolution, artists have experimented with the unique technological aspects of photography, pioneering new artistic realms. In the modern era, the advancement of digital media has solidified photography’s role as a powerful tool for generating novel visual experiences, transcending mere documentation or representation. Leveraging its inherent capacity for objective recording, artists have used photography to create “fantastical” spaces that do not exist in reality, while also transforming real spaces into dreamlike or imaginary realms through various camera techniques, development processes, and printing methods. In this way, photography has been employed both to construct and deconstruct our perceptions of reality, expanding its expressive potential.

This evolution underscores the idea that artistic perspectives on creative works have historically transformed and expanded in conjunction with the tools used to create them. The medium through which human expression is channeled plays a pivotal role in shaping artistic discourse and the evolution of artistic forms [38,39].

2.2. Neoplasticism (Nieuwe Beelding) Art

Neoplasticism, also known as De Stijl, was an influential artistic movement that originated in the Netherlands in the early 20th century, primarily active between 1917 and 1931 [40,41,42]. Centered around Theo van Doesburg, the movement encompassed various art forms, including painting, sculpture, architecture, and design. The term De Stijl was derived from the title of the group’s magazine, which served as a platform for disseminating their aesthetic principles. With the involvement of Piet Mondrian, the De Stijl journal became instrumental in promoting the movement’s ideas, with Mondrian regularly contributing his aesthetic views. Emerging in response to the chaos and destruction of World War I, the De Stijl movement sought to pursue abstraction, order, purity, and harmony in art and design. The movement’s ideas were widely promoted through the Dutch art and design journal De Stijl, which played a pivotal role in propagating the principles of Neo-Constructivism, an approach aimed at establishing a universal aesthetic language that transcended national boundaries.

De Stijl was among the first movements to systematically propagate the principles of the Plastic Arts across multiple artistic disciplines, drawing from early 20th-century Cubism. The group advocated for the integration of visual arts by proposing the treatment of all space as a flat plane and applying fundamental geometric shapes and primary colors, regardless of the medium—whether painting, architecture, or design. The movement’s ideology evolved from Mondrian’s Neoplasticism, which emphasized purity and intuition, to Van Doesburg’s Elementalism, which prioritized the tangible and concrete aspects of artistic form. By the 1920s, the influence of De Stijl had transcended the Netherlands, growing into an international Constructivist movement. Central to De Stijl’s philosophy was the unification of visual arts through a shared set of formal principles, treating spatial compositions as flat planes articulated through basic geometric forms and primary colors [43]. This marked a significant departure from the representational art of the past, paving the way for a more abstract and universal language of art and design [44].

The artists of De Stijl believed that true beauty emerged from the absolute purity of the artwork, rather than from the depiction of nature or reliance on external values and subjective emotions. Extensive artistic research has confirmed that the purification of art was central to the neoplasticist’s philosophy.

The artistic principles of neoplasticism can be summarized as follows: First, the neoplastic approach is characterized by a geometric, abstract tendency, emphasizing the use of fundamental geometric forms, such as squares, rectangles, and straight lines. These elemental shapes are arranged in a balanced and harmonious manner within the composition. Second, neoplasticists favored a limited palette, primarily employing achromatic colors—black, white, and gray—alongside the primary hues of red, blue, and yellow. Third, the simple geometric forms are often arranged asymmetrically, creating a sense of balance and harmony that moves away from strict geometric symmetry. The inclusion of diagonal elements further expresses this asymmetrical equilibrium. Fourth, the neoplastic approach is underpinned by a reductionist ethos, which seeks to distill art and design to their most fundamental elements, eliminating superfluous details in favor of pure form and color. Fifth, the use of abstraction and a universal visual language aims to transcend cultural and linguistic barriers, conveying a sense of universal harmony and order. Sixth, the neoplastic principles extended across various disciplines, with prominent architects such as Gerrit Rietveld and J.J.P. Oud contributing significantly to architecture and graphic design. Lastly, Piet Mondrian remains the most iconic figure associated with neoplasticism, his work profoundly influencing modern art. The neoplasticists’ emphasis on simplicity, abstraction, and universal harmony sought to provide a visual language that could embody utopian ideals and facilitate recovery in a post-war world.

The neoplasticism movement, sharing a similar perspective, was selected as a comparative area for this research. When neoplasticism first emerged, the art establishment initially did not recognize its works as legitimate art. These works were defined by the movement’s eight representative elements: vertical, horizontal, red, yellow, blue, gray, white, and black. Piet Mondrian, the leading figure of neoplasticism, made various attempts to gain recognition for neoplasticism as a legitimate art form. Initially incorporating Cubist techniques, Mondrian gradually refined and simplified his subject matter, focusing on expressing the purest essence of objects. This process of distillation and simplification led to the development of the neoplasticist style that is now widely recognized.

Despite initial resistance, Mondrian’s persistent efforts to establish neoplasticism as a valid artistic movement eventually succeeded. The stark, geometric compositions and limited color palette—once considered unconventional—became recognized as a distinctive and influential artistic language that embodied the neoplasticist’s pursuit of universal harmony and order. This research selects neoplasticism as a comparative framework, recognizing its shared perspective on the essence of art and the artistic development process that led to its eventual recognition and significant impact on the art world [45,46,47].

The characteristic composition of the neoplastic form must be a rectangular plane or prism composed of the primary colors red, blue, yellow and the achromatic white, black, and gray. In architecture, empty space is considered achromatic, and non-natural materials are perceived as colored. The dimensions and colors of the plastic medium must be equal, but their essential value is the same even if they are different. Balance generally means the relationship between large areas of achromatic or empty space and relatively small areas of color or material. The dual opposition in the plastic medium is also essential in the composition. Constant balance is achieved through the relationship between positions, which is expressed by the straight line that forms the boundary of the pure plastic medium. Balance neutralizes and annihilates the plastic medium, and creates a dynamic rhythm through the relationship of the arranged proportions. In addition, naturalistic repetition or symmetry must be strictly excluded [48].

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Methods and Components

The research methodology in this study consists of a framework of two main conditional backgrounds. It is “the aesthetic emotion criteria” by Monroe C. Beardsley and “the aesthetic experience standard” by Noël Carroll. The background conditions of these frameworks will be used to analyze the correlation between neoplasticism and the aesthetic principles outlined in the aforementioned criteria. Monroe C. Beardsley’s “Aesthetic Emotion Criteria” refer to specific emotional responses triggered by aesthetic experiences [49,50,51,52,53].

This framework will be used to explore how aesthetic characteristics and formal elements of neoplasticist artworks evoke specific emotional responses in viewers. On the other hand, Noël Carroll’s “Aesthetic Experience Standard” focuses on the essence of the aesthetic experience itself, emphasizing factors such as attention, cognitive participation, unity, or totality perception [54,55,56,57,58]. This approach will be applied to investigate how the unique visual expressions and principles of neoplasticism affect the overall aesthetic experience of viewers. This study aims to provide a comprehensive correlation analysis and insights into the aesthetic and empirical characteristics inherent in neoplasticist artworks by utilizing both Beardsley and Carol’s criteria as the main methodological background elements. The purpose of this study is to explain how artificial intelligence-generated creations and art trends movements match or differ from existing theories in aesthetic reactions and appreciation.

3.1.1. Application of Beardsley’s Aesthetic Emotion Criteria to Neoplasticist Art

Monroe C. Beardsley’s “Aesthetic Emotional Criteria” provides a valuable framework for analyzing emotional and formal characteristics of works of art, especially in terms of unity, strength, and complexity [59,60,61,62,63]. These criteria play an important role in analyzing how they influence neoplasticist art, which focuses on geometric abstraction and simplicity. Applying such Beardsley’s principles to neoplasticism allows us to better understand these emotional and constitutive characteristics of De Stijl.

Uniformity, defined by Beardsley, refers to the degree to which the various elements of a work of art are harmoniously integrated into a cohesive whole to form a consistency across the board. In the context of neoplasticism, these criteria are particularly relevant given De Stijl’s character, which focuses on balance and harmony. The work of neoplasticist artists, especially Piet Mondrian, demonstrates a high level of unity with its geometric shape and strict use of color palettes. The interaction of vertical and horizontal lines and the primary and achromatic tones of red, yellow, and blue combined to visually interconnect all parts of the work. The absence of unnecessary elements further represents cohesion, as formal elements are classified in their most essential forms. This focus on unity is fundamental to the neoplasticist work characteristics, where the integration of components creates a strong sense of order and balance.

Criteria for assessing the emotional or expressive power of works of art can also be observed in neoplasticist art. This type of characteristic deliberately avoids expressive images and emotional excesses, but the extent of the artistic value of such works stems from the precision and clarity of formal elements. Using bold primary colors of red, yellow, and blue juxtaposed with vertical and horizontal black-and-white lines and planes, a visual degree that captivates the viewer is formed. Despite abstraction, sharp contrast and rigorous geometry evoke energy and dynamism. Mondrian’s work, for example, achieves emotional resonance not through expressive images but through restrained simplicity, through which intensity is transmitted through the purity of form and color relationships. This minimalist approach allows viewers to experience subtle yet profound emotional depths consistent with Beardsley’s concept of intensity. In this study, these parts are applied as the background of the framework as the object of the analysis regulation of creations created by artificial intelligence.

By Beardsley’s definition, complexity refers to the diversity and complexity of components in a work of art. Neoplasticism features a reductionist approach, but nevertheless integrates it into a form that is seemingly simple but actually implies complexity. The complexity of neoplasticist art comes from the careful arrangement of geometric figures, lines, and colors. The flow of visual cognition is limited to basic forms and limited palettes, but the relationships between these elements are carefully constructed to create visual tension and harmony. The asymmetric equilibrium implemented in many neoclassical works contributes to this complexity, as the interactions of form and space produce dynamic interactions. This complexity is not explicit, but is embedded in subtleties of form and proportion, providing a layered aesthetic experience that induces deeper engagement in artistic works.

Beardsley’s aesthetic emotional standards of unity, strength, and complexity provide a structured lens, or composition of perspective, that allows us to assess the aesthetic and emotional impact of neoplasticist artwork. The focus of the trend analysis of geometric abstraction, balance, and harmony is closely aligned with the principle of unity, and the intensity of neoclassical works is conveyed through formal precision and clarity. Moreover, despite its minimalist approach, the complexity inherent in the compositional arrangement enriches the viewer’s experience. By applying Beardsley’s framework, we can better understand the emotional and aesthetic characteristics of neoplasticist artwork, and fully understand the appeal of the artistic value of neoplasticist tendencies to artificial intelligence-generated creations.

- (1)

- Unity = Evaluation of consistency among the parts/Evaluation of overall consistency of the artwork

Unity refers to the degree to which various parts of a work created by artificial intelligence are harmoniously integrated to convey consistency throughout the work.

- (2)

- Intensity = Evaluation of the intensity of emotion

Intensity refers to the degree of emotional or expressive power delivered by a neoplasticist work of art created by artificial intelligence.

- (3)

- Complexity = Evaluation of diversity and complexity

Complexity refers to the degree to which various and complex components are included for artistic creations of artificial intelligence.

3.1.2. Application of Carroll’s Aesthetic Experience Criteria to Neoplasticist Art

Noël Carroll’s “aesthetic experience criteria” provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the formal, aesthetic, expressive, and relational aspects of an artwork. By applying these criteria to neoplasticist art, we can better understand how its visual language, which emphasizes abstraction and minimalism, delivers an impactful aesthetic experience. Carroll’s components—form, aesthetic beauty, emotional expression, and the correlation of areas—allow for a multidimensional analysis of neoplasticist works [64].

Carroll’s criterion of form refers to the structural characteristics of the artwork, including the organization of its visual elements. In neoplasticism, form plays a central role in shaping the viewer’s experience. The movement’s hallmark is its use of rigid geometric shapes, primarily rectangles and squares, arranged within a grid-like structure. The strict organization of these shapes, combined with the use of horizontal and vertical lines, creates a coherent visual framework. This clarity of form is essential to the movement’s goal of achieving order and harmony. By reducing the composition to its most basic elements, neoplasticist artists, particularly Piet Mondrian, sought to convey a universal visual language that transcends individual subjectivity. The structural rigor of neoplasticist form invites the viewer to focus on the interplay between shapes, lines, and colors, fostering a sense of balance and unity.

The aesthetic components of Carroll’s framework relate to the evaluation of the beauty and harmony seen in neoclassical works of art. Neoplasticism aesthetics are defined by the purity and simplicity of carefully arranging the primary colors of red, yellow, and blue along with the achromatic colors of black, gray, and white. The art trend’s commitment to artificial intelligence’s creative forms reinforces its aesthetic appeal by eliminating external details and focusing on the essence of visual experience.

Using flat and clean lines, you can feel spatial harmony, and the vivid contrast between primary and neutral tones intensifies the display of visual influences. Mondrian’s composition, for example, demonstrates a delicate balance between tension and harmony as the interaction of lines and colors creates an aesthetically pleasing yet dynamic visual experience. This emphasis on formal beauty is a rational application of Carroll’s aesthetic concepts related to the harmonious arrangement of elements of artworks created by artificial intelligence.

Carol’s expressive aesthetic standards assess the extent to which artworks created by artificial intelligence convey emotions or messages. Neoplasticism is mainly about form and structure, but it also has an expressive high-level dimension. The abstraction of this trend, De Stijl, may seem devoid of emotional content at first glance, but upon closer inspection, the careful coordination of lines, figures, and colors conveys a deeper sense of order and utopia ideals. The emotional resonance of neoplasticism is meant for evaluative values in expressing universal concepts of harmony, balance, and clarity. By eliminating confusion-prone personal subjectivity and focusing on pure abstraction, this trend, De Stijl, expresses a vision for a more orderly and harmonious world, especially in response to the chaos of the early 20th century. With its rigorous geometric structure and vivid color contrast, Mondrian’s composition reflects this De Stijl’s broad philosophical and aesthetic goals, evoking calm, stability, and optimism. In contrast to human-created works in this area, it is appropriate for AI-created frameworks for artistic valuation [65,66].

The relative importance of each component in the correlation analysis of domains is critical to understanding the overall aesthetic experience of neoplasticist artworks. In neoplasticism, the structural organization of lines and figures is prioritized in form because it is the basis of the aesthetic sense. However, aesthetic beauty and expressive content are equally important because the simplicity and clarity of the composition contributes to both the visual pleasure and emotional impact of the work. The balance between these components—formal, aesthetic, and expressive—creates a unified experience where each element enhances the other.

De Stijl’s reliance on abstraction ensures that none of the elements dominate the composition, instead combining form, color, and representation tasks to create cohesive and harmonious visual languages for artificial intelligence-created works. Correlations in these domains reflect the nature of neoplasticism towards universal art forms that transcend individual artistic preferences, emphasizing the collective vision of order and harmony. Neoplasticist art can analyze artificial intelligence-created works with cohesive, multidimensional visual experiences by applying the correlation of form, aesthetic, expressive, and domain, which is Carroll’s standard of aesthetic experience. The structural clarity of De Stijl, the emphasis on aesthetic harmony, and the subtle expressive content combine to create strong aesthetic value. Through the careful balance of these components, neoplasticism makes a special contribution to artworks created by artificial intelligence, embodying a vision of universal beauty and composition that sympathizes with Carroll’s principles of aesthetic experience.

- (1)

- Form = Evaluation of structural characteristics

Form refers to the structure and organization of neoplasticist works of art created by artificial intelligence.

- (2)

- Aesthetic = Evaluation of beauty

The aesthetic element refers to the beauty and harmony of the neoplasticist works of art created by artificial intelligence.

- (3)

- Expressive = Evaluation of emotional expression

The expression component refers to the degree to which a neoplasticist work of art created by artificial intelligence conveys an emotion or message.

- (4)

- Correlation of Areas = Evaluation of the importance of each area

Correlation between the various components in the neoclassical creations created by artificial intelligence reflects the relative importance of each domain and its impact on the overall aesthetic experience [67].

3.2. Research Data Analysis and Procedures

The hypothetical evaluation formula can be understood as a model for quantitatively evaluating the aesthetic value or beauty of artificial intelligence-generated neoplasticist works of art. From an artistic engineering perspective, ‘artistic attraction’ represents the overall degree of attractiveness or aesthetic quality of a given work of art, which serves as an analytical function target as an output variable. The input variables that affect this output include factors such as Unity, Intensity, Complexity, and others that measure the consistency, emotional power, and complexity of the work, respectively.

The β values associated with these input variables are used as weighting coefficients and represented as coefficients affected by the relative significance or influence of each element on the overall artistic appeal.

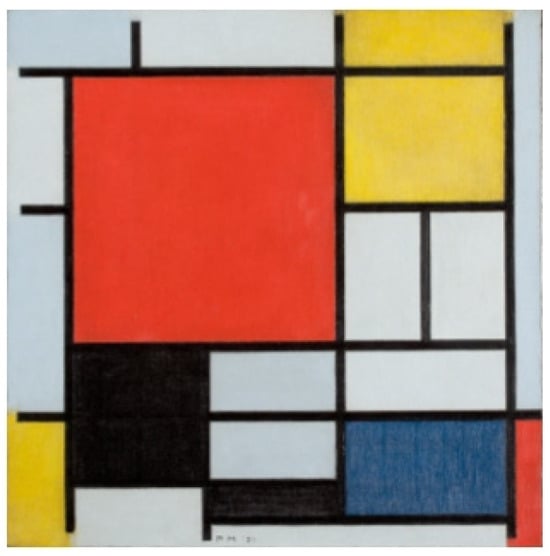

Figure 1 displays Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, Blue, and Black (1920), an iconic work of neoplasticism. It features a balanced arrangement of geometric shapes, primarily squares and rectangles, filled with primary colors—red, yellow, blue—along with black and white. The composition exemplifies Mondrian’s pursuit of harmony through abstraction.

Figure 1.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Red, Yellow, Blue, and Black, 1920.

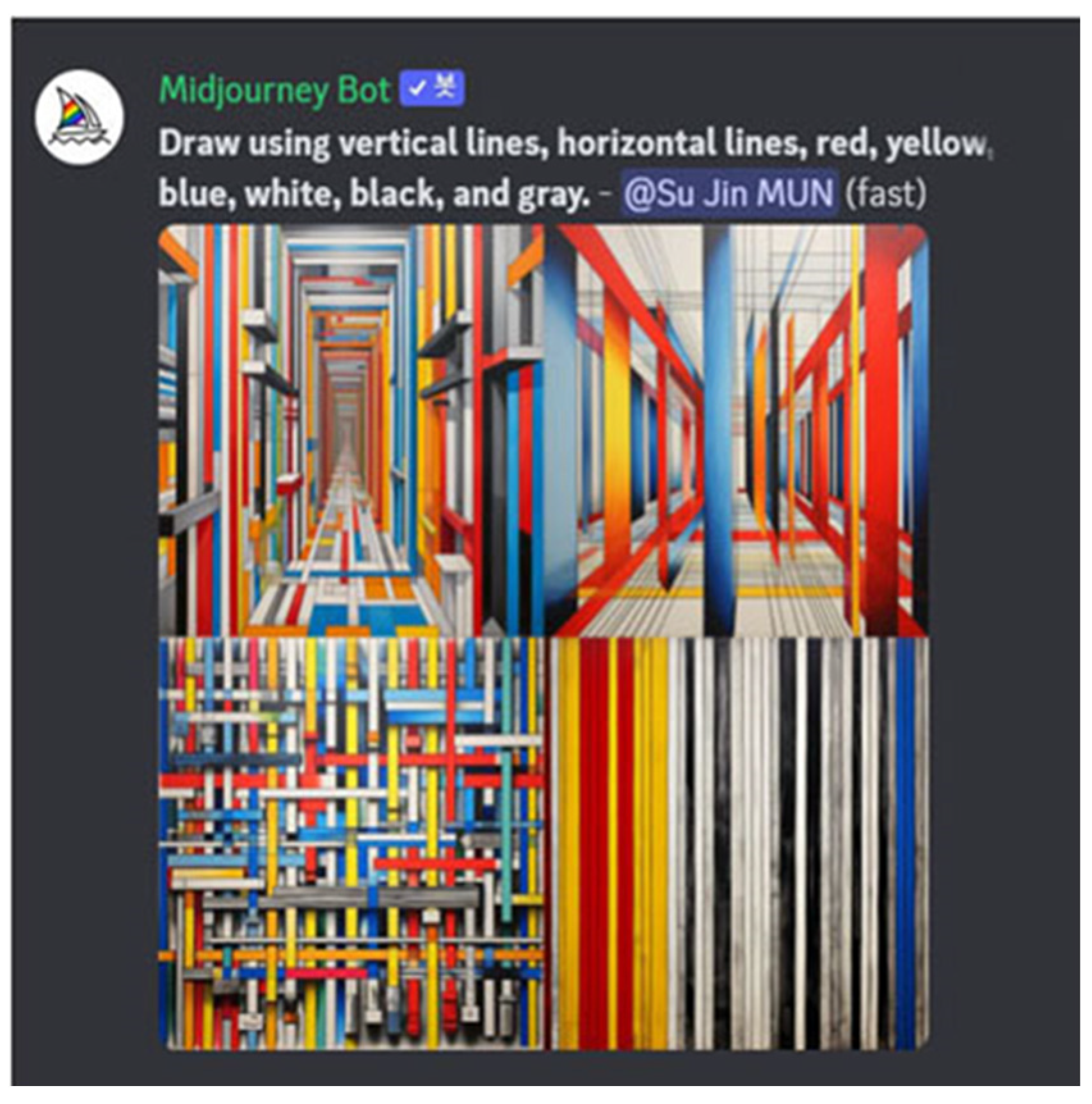

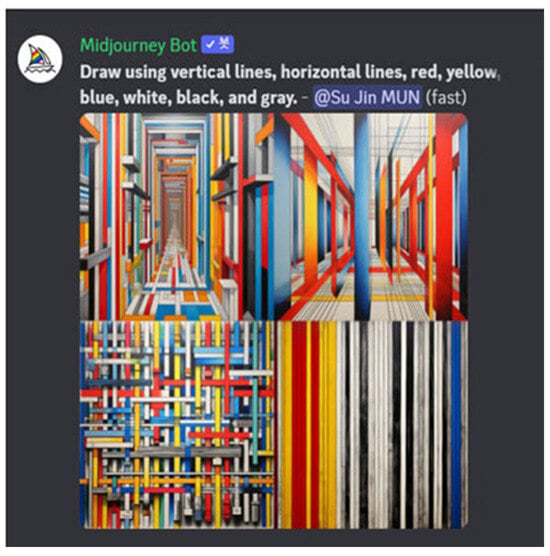

Figure 2 shows a series of artificial intelligence-generated artworks created using the Midjourney platform [68,69,70]. The works feature vertical and horizontal lines, combined with a color scheme of red, yellow, blue, white, black, and gray, closely mimicking the geometric and color principles of neoplasticism. The resulting compositions explore complex spatial arrangements through abstract forms.

Figure 2.

AI-generated artwork based on neoplasticist principles prompted by Su Jin MUN using Midjourney.

By quantifying these variables through the evaluation of actual artworks and applying them to the formula, the resulting score would offer a quantitative assessment of the artwork’s beauty or artistic merit. This approach enables a systematic, data-driven evaluation of aesthetic qualities, moving beyond the reliance on purely subjective human judgment. From a technical perspective, the formula seeks to distill the multifaceted aspects of artistic appeal into a composite measure. The input variables represent key compositional and perceptual elements that are hypothesized to contribute to the overall aesthetic experience.

By weighting these factors according to their relative importance, as determined by the β coefficients, the model aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the artwork’s artistic appeal. Ultimately, this quantitative assessment framework, grounded in an art engineering perspective, offers a structured methodology for analyzing and understanding the aesthetic properties of artworks. While the subjective nature of art appreciation cannot be fully encapsulated by such formulas, this model provides a systematic means of evaluating and comparing artistic works based on measurable criteria.

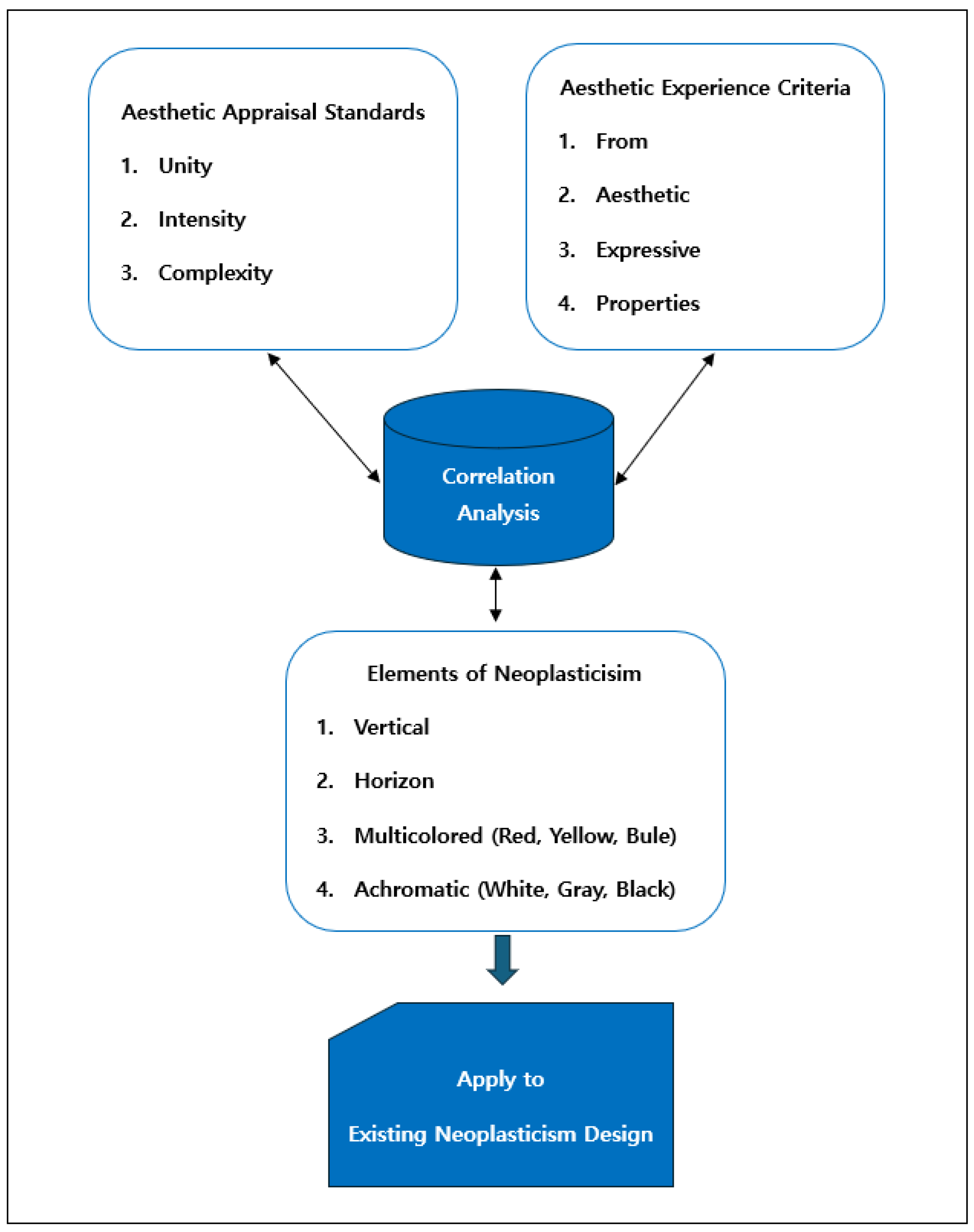

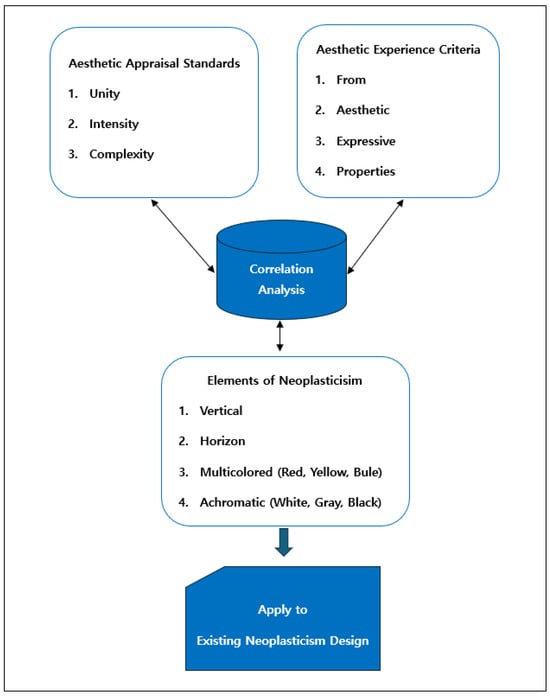

Figure 3 presents a framework that integrates aesthetic appraisal standards and aesthetic experience criteria to analyze neoplasticism design elements. The aesthetic appraisal standards include Unity, Intensity, and Complexity, while the aesthetic experience criteria consist of Form, Aesthetic, Expressive, and Properties. These inputs undergo correlation analysis to evaluate their relationship with key neoplasticism elements, such as vertical and horizontal lines, primary colors (red, yellow, blue), and achromatic colors (white, gray, black). The results of this analysis are then applied to existing neoplasticism designs, enabling a systematic approach to understanding and assessing their aesthetic and experiential qualities.

Figure 3.

Research Procedure.

3.2.1. Hypothetical Evaluation Formula

The Hypothesis Assessment Formula for “Artistic Appeal” is a quantitative model designed to evaluate the aesthetic value of artworks created by artificial intelligence by integrating the neoplasticist framework components and perceptual elements. The functional equation formula is represented by a linear combination of key characteristics such as Unity, Intensity, Complexity, Form, Aesthetic, Expressive qualities, and the Correlation of Areas, and certain neoplasticist elements such as vertical and horizontal lines, primary and achromatic systems. Each of these components reflects the important properties of a work of art, and the β value represents a weighting parameter that determines the relative importance of each element. These parameters should be optimized by learning modeling through algorithmic analysis to accurately assess the overall artistic attractiveness of a work of art. The model provides the reliability of the appropriateness of a structured framework to analyze and compare artworks created by artificial intelligence by measuring and analyzing these factors systematically.

Artistic Appeal = β0 + β1 × Unity + β2 × Intensity + β3 × Complexity + β4 × Form + β5 × Aesthetic + β6 × Expressive + β7 × Correlation of Areas + β8 × Vertical + β9 × Horizontal + β10 × Colorful + β11 × Monochromatic

Independent variables can be defined as follows:

Each of the variables (Unity, Intensity, Complexity, Form, Aesthetic, Expressive, Correlation of Areas, Vertical, Horizontal, Colorful, and Monochromatic) represents distinct characteristics that contribute to the overall artistic appeal of a work. The coefficients (β0, β1, …, β11) are weight parameters that must be optimized through model training to achieve the most accurate evaluation of the artwork. These parameters determine the relative importance of each factor in contributing to the final assessment of artistic appeal.

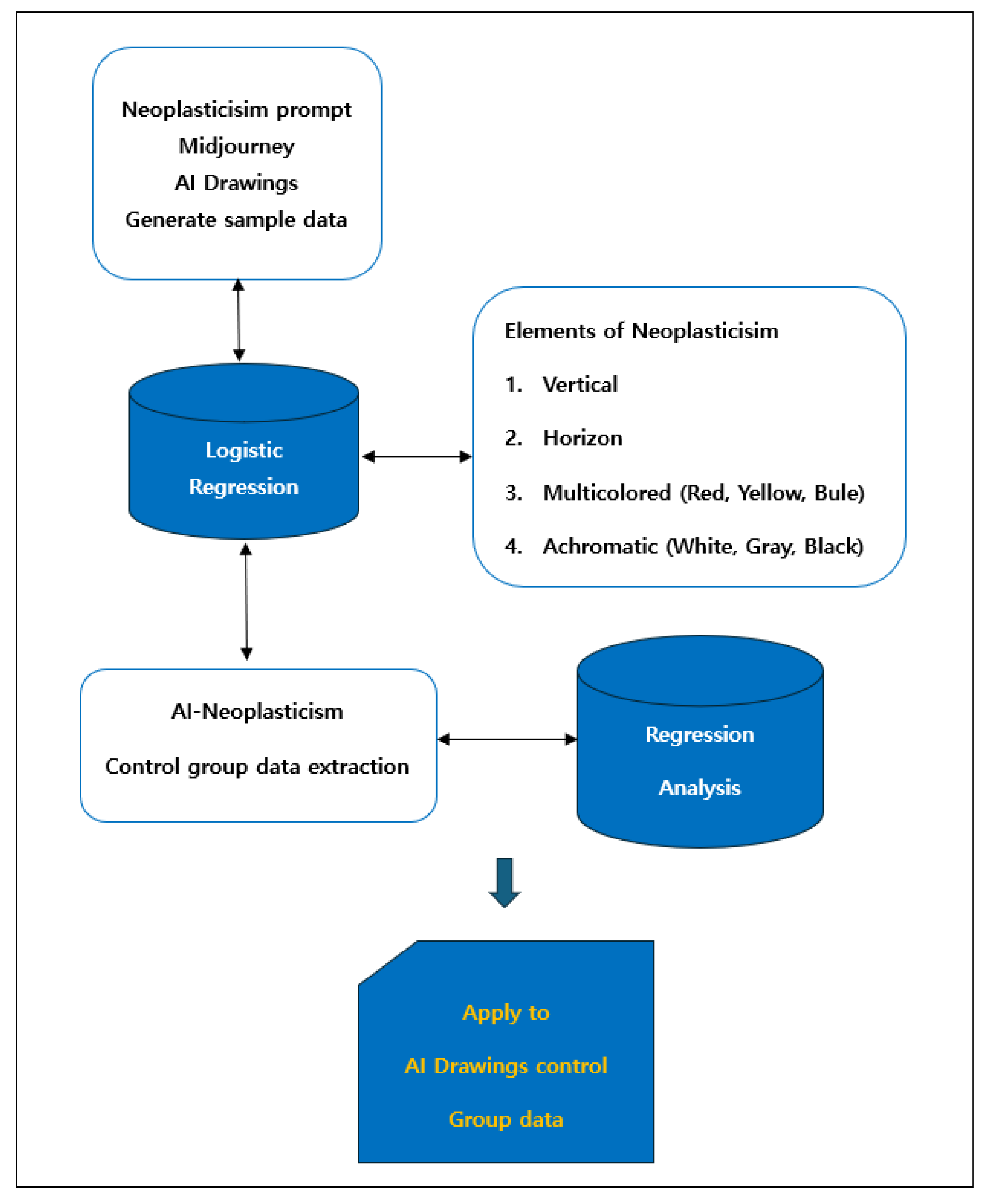

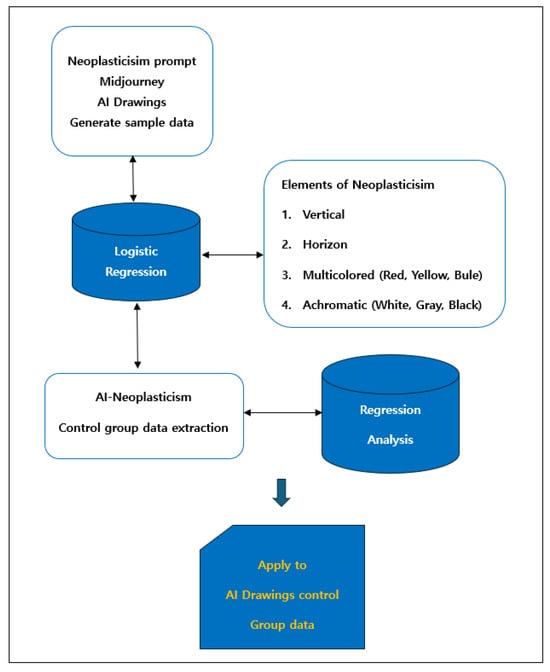

Figure 4 illustrates the process of analyzing AI-generated neoplasticist drawings using logistic and regression analysis. The neoplasticism prompt in Midjourney generates sample data, which are then analyzed through a logistic regression. The key elements of neoplasticism—vertical, horizontal, multicolored, and achromatic—are identified and compared with a control group of AI-generated artworks. The regression analysis further refines the results, which are ultimately applied to the AI drawings control group for comprehensive evaluation.

Figure 4.

Applying analysis of AI-generated neoplasticism prompts and control group data.

3.2.2. Application of Logical Regression Formula

The hypothetical logistic regression model for predicting the likelihood of a “Good Artwork” is expressed as

- (i)

- In this formula, P (Good Artwork) represents the probability that an artwork is deemed “good”.

- (ii)

- The β coefficients () are parameters that the model learns during the training process, indicating the impact of each variable on the classification outcome.

- (iii)

- The input variables correspond to measurable characteristics of the artwork that contribute to its overall evaluation.

In this formula, P (Good Artwork) represents the probability that a given artwork is classified as “good”. The variable ‘e’ refers to the natural constant, and expresses the inverse probability of an artwork being considered “Good”, and β0, β1, β2, β3, β4 are the weight parameters learned during the logistic regression process. The input variables—Vertical, Horizontal, Colorful, and Monochromatic—correspond to the quantitative characteristics of the artwork, representing vertical and horizontal elements as well as polychromatic and achromatic color schemes.

The β values are adjusted through training on a dataset consisting of multiple artworks, each evaluated for its neoplasticist features. This model allows for the systematic prediction of the aesthetic quality of artworks by correlating formal characteristics with artistic merit.

3.2.3. Logistic Regression Analysis of AI-Generated Neoplasticist Artworks

To analyze how effectively AI-generated artworks reflect the characteristics of neoplasticism, such as vertical, horizontal, and diagonal elements, a logistic regression analysis was conducted. Through this method, the research team identified the compositional elements that the AI model recognized as essential for generating neoplastic artworks, and how these elements were manifested in the resulting pieces. The analysis revealed that the AI model consistently identified geometric forms, particularly vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines, as core elements, and these characteristics were prominently reflected in the generated artworks.

By employing this statistical approach, the research team was able to systematically extract the key features of neoplastic art and conduct an in-depth analysis of the AI-generated art creation process. From an aesthetic experience perspective, the team also examined how the unity, balance, and rhythm inherent in neoplastic artworks might influence viewers’ aesthetic emotions. Overall, this analytical approach provided valuable insights into the AI model’s learning process and the extent to which it successfully incorporated neoplasticist principles into its generated artworks, along with the potential aesthetic implications for the audience’s experience.

3.3. Research Evaluation Method

The presented formula for quantifying the artistic appeal of AI-generated Constructivist artworks illustrates how the influence of various characteristics, such as Unity, Intensity, and others, on the overall artistic appeal is represented through weighted parameters (β). This model serves as a criterion for evaluating the quality of an artwork, with the optimal values for each parameter determined through training on relevant datasets.

The equation expresses Artistic Appeal as a linear combination of several characteristics, where β0 denotes the intercept, reflecting the baseline value of Artistic Appeal. The remaining β1 to β6 represent the weights assigned to each characteristic, indicating their relative importance.

Additionally, the model incorporates a logistic regression to evaluate the probability of an artwork being classified as “Good”. Logistic regression, a technique used for categorical dependent variables, is applied here to assess whether an artwork falls into the “Good” or “Not Good” category. The log odds equation is shown in Equation (2).

In order to apply this model, art pieces have to be collected where every piece has to be classified as ‘Good’ or ‘Not Good’. These labels will be used in the process of fine tuning ngthe weight parameters (β) of the model. Consequently, the model will be able to predict the value of art as closely as possible as it will be provided with real-life data after the parameters which regulate it have been optimized.

where is the constant term, is the coefficient for each independent variable , and is the error term.

4. Research Results and Description

4.1. Research Results

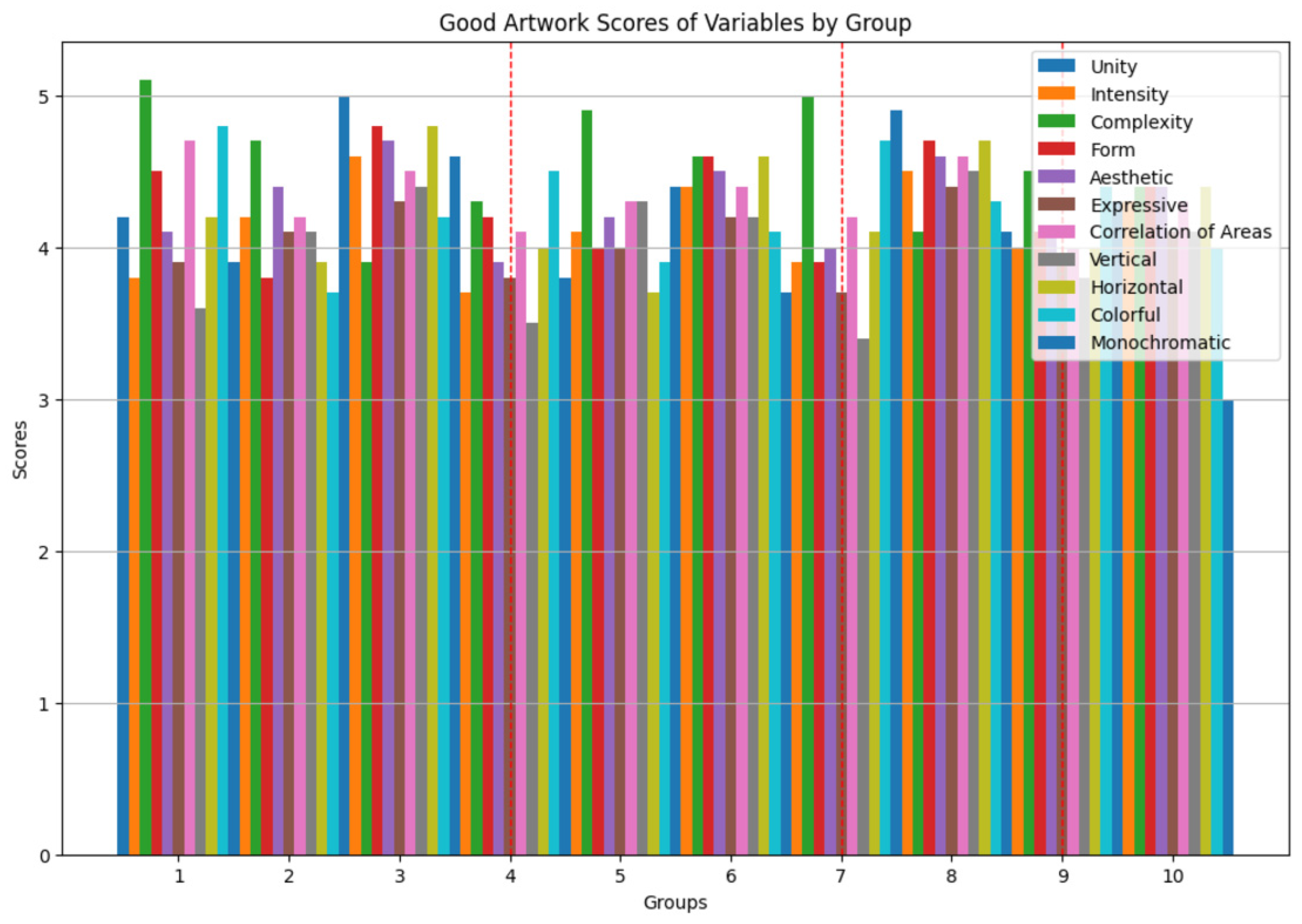

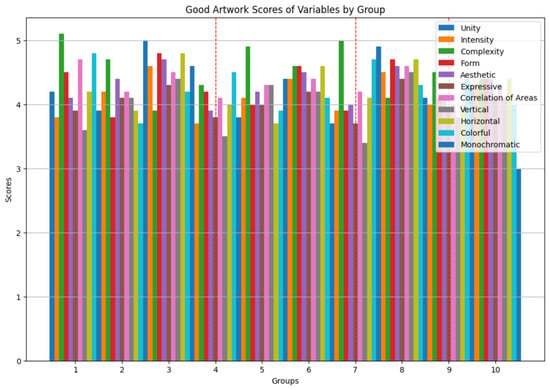

The results of the study provide analysis and insights into various factors that influence the classification of artificial intelligence-created neoplasticist works as “Good Artwork” The analysis categorized 100 created works of art into 10 groups, each of which was evaluated and analyzed by applying 12 individual function variables which are Unity, Intensity, Complexity, Form, Aesthetic, Expressive, Correlation of Areas, Vertical, Horizontal, Colorful, Monochromatic, and Artistic Appeal. The “Good Artwork” variable, which is used as a dependent binary outcome, indicates whether the artwork can be classified as a good work (1) or not (0).

Using variables from the aforementioned equations, logical regression analysis was calculated to investigate and analyze the impact on artworks created by artificial intelligence on their likelihood of being classified as “Good”. As summarized in Table 1, the results showed that there was a significant difference in the importance of each element. In particular, Unity, Complexity, Aesthetic, and Artistic Appeal were positively correlated with a high probability of a work of art being classified as “Good”. For example, among the works of art in Group 3, works with high scores in Unity (5.0), Artistic Appeal (4.8), and Aesthetic Appeal (4.7) consistently obtained results of being classified as good values.

Table 1.

Evaluation of AI-Generated Neoplasticist Artworks Across Multiple Variables and Their Classification as “Good Artwork”.

Conversely, as shown in Group 4, groups with lower scores in key framework areas such as Unity and Complexity were less likely to be classified as “Good Artwork”, and in the analysis of works, strong correlations were found between vertical and horizontal elements, especially in these areas, where works created by artificial intelligence with balanced scores tend to have higher artistic valuations.

The model successfully identified which compositional elements were most influential in determining the artistic quality of AI-generated neoplasticist artworks, allowing for a systematic evaluation of artistic appeal across various dimensions.

4.2. Analysis of AI-Generated Neoplasticist Artworks

The data analysis results generated 100 creative works titled ‘MUN, Su Jin’ by utilizing the AI Midjourney system according to the criteria set by Monroe C. Beardsley and Noël Carroll to evaluate artworks inspired by neoplasticist creations, and derived insights through research to evaluate their aesthetic value by analyzing the results of the algorithm used in them. According to the results of this study, most artworks created by artificial intelligence received high evaluation scores for their artistic value, demonstrating the outstanding creative ability of the artificial intelligence system. Each artwork was grouped into 12 criteria, and an evaluation score category between 1.0 and 5.0 points was applied.

The analysis results can be summarized as follows. The overall quality of the neoplasticist works created by artificial intelligence was consistently high, and most of them had a score distribution of more than 4 points on the main criteria such as Unity, Intensity, Complexity, Form, Aesthetic, Expressive, Correlation of Areas, Vertical, Horizontal, Colorful, Artistic Appeal, and Good Artwork. These results lead to excellent creativity in creating neoplasticist works with aesthetic value of artificial intelligence artistic creations created with the AI Midjourney system.

The variability between the artworks was minimal, with relatively uniform scores, indicating consistent quality throughout the collection. However, the Monochromatic criterion exhibited a broader range of scores, from 2.1 to 3.2, highlighting a comparatively lower diversity in the use of monochromatic elements. While most artworks received high evaluations, the Good Artwork criterion revealed a few pieces that scored only 1 point, which allowed for the selection of the most outstanding works. A potential area for improvement lies in the Monochromatic criterion, where lower scores suggest that enhancing color diversity could be a beneficial development direction for the AI_Midjourney system.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that the AI_Midjourney system possesses exceptional creative capabilities, consistently producing artworks of high quality. Its strong performance on criteria such as Colorful, Artistic Appeal, and Good Artwork indicates that it is capable of generating pieces with substantial artistic merit, extending beyond basic geometric structures. Nevertheless, the relatively lower scores in the Monochromatic category suggest the need for further refinement to improve color diversity, an important consideration for advancing AI-generated art.

This study provides empirical evidence of the AI_Midjourney system’s ability to effectively implement the core principles of neoplasticism, successfully capturing key aesthetic characteristics of the movement, including geometric forms, color, and structural harmony. The positive evaluation of algorithm-based artistic creation contributes valuable insights to future research in this domain [71,72].

Figure 5. The results of the graph analyzed 12 factors influencing the classification of “Good Artworks” in AI-created neoplasticism artworks. Categorizing 100 works into 10 groups, they were evaluated based on 12 variables (Unity, Strength, Complexity, Form, Aesthetic, Expressive Power, Domain Correlation, Vertical, Horizontal, Colorful, Monochromatic, and Artistic Appeal). The “Good Artworks” variable is a binary dependent variable that the artwork is classified as Good (1) or Bad (0).

Figure 5.

MUN, Su Jin by AI_Midjourney 100 creative works (2023–2024).

- (i)

- Focusing on Unity, Aesthetics, and Artistic Appeal, Group 3 scored the highest and was classified as a “good work of art”. The group scored high on Unity (5.0), Artistic Appeal (4.8), and Aesthetic (4.7), showing that these variables positively influence the quality of the artwork.

- (ii)

- In terms of complexity, Group 3 and Group 6 scored relatively high in Complexity, and these groups were classified as “Good Artwork”. This suggests that Complexity is an important factor in artistic quality.

- (iii)

- Groups 4, 7, and 9 are not classified as “Good Artwork”. In particular, Group 4 scored above-middle in Unity (4.6), Complexity (4.3), and Aesthetic (3.9), but was not evaluated as Good Artwork due to the lack of overall harmony and balance.

- (iv)

- Group 7 scored lower in Unity (3.7), Aesthetic (4.0), and Artistic Appeal (3.9). In particular, Unity and Complexity’s poor scores are analyzed to be the main reason the work was not classified as “Good”.

- (v)

- Group 9 scored in Unity (4.1), Complexity (4.5), and Aesthetic (4.1), but was rated “Not Good” due to a lack of overall balance.

- (vi)

- Works with a good balance of vertical and horizontal plane elements tend to gain high artistic appeal. Group 3 and Group 6 were classified as “Good Artwork” for scoring high in these two factors.

Variables in the use of multicolored and achromatic colors act as important factors in determining the visual appeal of the work, and the higher the Colorful score, the higher the probability of being classified as Good Artwork.

Through logistic regression, researching the results of the effect of each variable on the probability that the artwork was made by grouping AI-created work would be classified as “Good”, and Unity, Complexity, Aesthetic, and Artistic Attraction showed positive correlations. For example, Group 3, which scored higher for Unity (5.0), Artistic Attractiveness (4.8), and Aesthetic (4.7), were consistently classified as “Good” works of art. On the other hand, Group 4, which had lower unity and complexity, was less likely to be classified as “Good works of art”. Strong correlations between vertical and horizontal that are basic elements of neoclassical abstraction were also found, so works with a good balance of these two elements tended to receive high artistic evaluation.

5. Discussion

The results found in this study show important insights into the uniformity, geometric composition, and balanced artistic sensibility evaluation of AI-generated neoplasticist art creations. When using the data collected for this study and comparing it with the aesthetic criteria set by Monroe C. Beardsley and Noël Carroll, this study will seek to determine how well the Midjourney AI performed creating in the neoplastic art features which encompass the use of lines and sides including the vertical, horizontal, and diagonal as well as color variety and structural balance.

Through insights analyzing the results of this study, the overall concentration of the score distribution on most criteria of Unity, Strength, Form, and Artistic Appeal is shown. These findings indicate that AI systems can produce works of artistic value that represent a sense of cohesion and balance as a result of robust learning. According to the analysis of the findings, the consistent display of the unity scores between 4 and 5 suggests that various neoconservative elements are harmoniously and consistently applied to AI-generated artworks. This is important, in other words, because unity is a fundamental principle of neoplasticism, which aims to simplify form and composition in order to organize well. In this respect, the results of the study also show that it is in line with previous studies on AI-generated art, where researchers found that AI models are particularly good at implementing structural harmony and balance in abstract visual art forms [73,74].

However, if the results are carefully analyzed and interpreted, it can be seen that there are several limitations to AI’s ability to fully machine-learning all the characteristics of neoclassical tendencies. Most notably, the achromatic standard had a low score distribution, ranging from 2.1 to 3.2. This suggests that AI’s ability to learn and implement the neoclassical characteristic of neoplastic composition has produced good results, but its ability to learn and process calm achromatic characteristics has not yet been fully developed. It can be seen that AI systems, such as Midjourney, which produce visual creations, are somewhat challenged by the subtle issues of achromatic analysis and learning, which require a subtle understanding of contrast, range, and depth of color. That may be due to the inherent complexity of achromatic configurations, which rely heavily on the delicate interactions between light and shadow, in which case AI models may not yet be fully grasped by algorithms. As interpreting the observations through below Table 2. summarizing evaluation main criteria and scores for AI’s neoplastic artwork, It shows that there are still some limitations in the application of AI learning to achromatic colors.

Table 2.

Summarizing evaluation main criteria and scores for AI’s neoplastic artwork.

The data also highlighted the relatively uniform scores across most criteria, indicating consistent quality across the body of artworks produced. This consistency is a strength of AI-generated art, as the algorithm ensures that the essential principles of neoplasticism, vertical and horizontal lines, geometric forms, and color balance, are applied evenly throughout each composition. This finding is supported by previous research, which has shown that AI systems excel in maintaining consistency across multiple works, as they apply the same learned rules and parameters to each new piece. However, the uniformity also raises questions about the AI’s ability to push creative boundaries. While human artists often experiment with form, color, and composition to create unique and innovative works, AI-generated art tends to follow a more formulaic approach, as it is bound by the rules and parameters set during the training process.

A particularly interesting finding from the analysis is the strong performance in the colorful criterion, which consistently scored between 4.0 and 4.7. This indicates that the AI model was particularly adept at employing a diverse color palette in its compositions, a key feature of neoplasticism, which often uses bold primary colors in stark contrast with black and white. This suggests that the AI has successfully internalized one of the core visual elements of neoplasticism, further demonstrating its capability to produce works that align with the aesthetic principles of the movement. It also notes the strength of AI in handling color diversity, where color plays a pivotal role in the overall composition.

While the AI model demonstrated a high level of proficiency in replicating the structural and aesthetic qualities of neoplasticism, the study also reveals areas for future improvement. For instance, the lower scores in the monochromatic criterion suggest that the AI might benefit from further training focused on more subtle and restrained color schemes. Enhancing the algorithm’s understanding of how to manage monochromatic elements could lead to a more comprehensive artistic output, better reflecting the full range of neoplasticist techniques. Additionally, future studies might explore how AI can be programmed to introduce more variability and creative risk into its compositions, rather than simply reproducing established patterns with high consistency.

The results of this study show that among artificial intelligence system technologies, in particular, the utilization term Midjourney system in the course of this study has significant capabilities in generating artificial intelligence-created neoplasticist artworks and has ample potential to develop more spectacularly in the future. Artificial intelligence has captured many key components of De Stijl, including uniformity, compositional form, color diversity, and contrast, but shows that there is still room for improvement in dealing with black, gray, and white achromatic colors more subtly and closely.

These findings contribute to the development of convergent research on artificial intelligence and art creations, and provide insight into the strengths of artificial intelligence as an art creation tool and its limitations that need to be gradually developed in the future. In particular, if we push the limits and continue to research and improve algorithms for more detailed computational learning, the complex artistic value of works created by artificial intelligence systems will be highly appreciated in the future [75].

6. Conclusions

Our study provides theoretical contributions to the existing body of knowledge on AI-generated art and aesthetic evaluation. While previous research has explored the capacity of AI systems to replicate artistic styles, much of this work has focused on the technical aspects of algorithm development and visual reproduction. These studies often overlooked the finer aesthetic principles of specific artistic movements, such as neoplasticism, especially regarding how AI systems engage with the core tenets of balance, harmony, and structural coherence [76,77,78].

This paper contributes by applying a structured, quantitative evaluation model that integrates both Monroe C. Beardsley’s aesthetic emotion criteria and Noël Carroll’s aesthetic experience criteria. By doing so, it provides a deeper understanding of how AI systems like Midjourney can successfully internalize and reproduce the essential characteristics of neoplasticist art, such as Unity, Intensity, and Form. Importantly, this study identifies gaps that previous research failed to address. Earlier studies have largely emphasized AI’s success in replicating bold and colorful designs, but they did not examine the AI’s limitations in handling more subtle aspects, such as monochromatic compositions. This research highlights that while AI excels in creating vibrant, complex designs, it struggles with the more restrained, minimalist aspects of neoplasticism, an insight not previously explored in-depth. For scholars, this study provides a new avenue for exploring AI’s engagement with aesthetic principles across diverse artistic movements. It suggests that future research should focus on how AI systems can be refined to incorporate a wider range of compositional subtleties, particularly in minimalist and monochromatic forms of art. This paper also implies that interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers and art historians could yield richer insights into the creative potential of AI technologies.

This study offers the practical implications for practitioners in fields related to AI and art creation. For artists using AI, this study provides valuable insights into how AI systems like Midjourney can be harnessed to generate high-quality artworks that align with specific artistic movements, such as neoplasticism. Artists can use these findings to better understand how AI interprets core visual elements like geometric forms and color contrasts, enabling them to collaborate with AI systems more effectively. For instance, artists could intentionally integrate the AI’s strengths in color diversity into their workflows while compensating for the system’s limitations in monochromatic compositions. For the art industry, these findings demonstrate the potential of AI as a tool for creating consistent, high-quality art. Galleries and curators might consider incorporating AI-generated artworks into their collections, especially for exhibitions focused on modernist or abstract movements.

This research shows that AI systems can produce artworks that not only adhere to the aesthetic principles of specific movements but also maintain a high degree of artistic appeal, which could have significant commercial value. AI developers can also benefit from these insights. The study highlights the areas where AI models excel, such as in creating visually striking and complex compositions, while also pointing out areas for improvement, such as handling minimalist or monochromatic designs. Developers can refine their algorithms to address these limitations, potentially by incorporating more advanced techniques in color management and shading. This could result in more versatile AI systems that can cater to a broader range of artistic styles and preferences. Lastly, art viewers and critics might use these insights to better appreciate AI-generated art. By understanding the strengths and limitations of AI models in producing different aesthetic experiences, viewers can engage more critically with AI-generated artworks, recognizing both the technical and creative aspects of these pieces. This contributes to a broader cultural acceptance of AI as a legitimate tool in artistic creation.

One limitation of this study is its reliance on a single AI system, Midjourney, which may not fully represent the capabilities of other AI models in producing neoplasticist art. Additionally, the evaluation focused heavily on visual characteristics, leaving out potential auditory or multi-sensory dimensions that could be explored in AI-generated art. Future research should include a comparative analysis of multiple AI systems to understand the broader applicability of the findings. Expanding the scope to include multi-sensory AI-generated art could open new pathways for exploring the intersection of AI and human creativity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.M. and W.H.C.; methodology, S.J.M.; formal analysis, S.J.M. and W.H.C.; data curation, S.J.M.; writing—original draft, S.J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Brain Korea 21 (BK21-4120240915063).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. A Comprehensive Survey of AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A History of Generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.I. The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turkmenoglu, A. Just Another Summer or a New Era: Artificial Authors. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2023. Available online: https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/14357 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Schmidhuber, J. Developmental Robotics, Optimal Artificial Curiosity, Creativity, Music, and the Fine Arts. Connect. Sci. 2006, 18, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorduck, P. Aaron’s Code: Meta-Art, Artificial Intelligence, and the Work of Harold Cohen; Macmillan: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, L. Mind, Machine, and Creativity: An Artist’s Perspective. J. Creat. Behav. 2014, 48, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, G.; Davis, E.; Aaronson, S. A very preliminary analysis of DALL-E 2. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermerén, G. Art and Artificial Intelligence. In Elements in Bioethics and Neuroethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinic, E.; She, J. Understanding and Creating Art with AI: Review and Outlook. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2022, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anantrasirichai, N.; Bull, D. Artificial Intelligence in the Creative Industries: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 589–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-R. A Study on the De Stijl’s Characteristics via Gropius’s Architecture. J. Korean Digit. Archit. Inter. Assoc. 2005, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ligêza, A. Logical Foundations for Rule-Based Systems; Kacprzyk, J., Ed.; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, D. Quantifying Inductive Bias: AI Learning Algorithms and Valiant’s Learning Framework. Artif. Intell. 1988, 36, 177–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgammal, A. Can: Creative Adversarial Networks, Generating “Art” by Learning about Styles and Deviating from Style Norms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.07068. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M. The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. In Proceedings of the 2021 Summit of the International Society for the Study of Information, Online, 12–19 September 2022; Volume 81, p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, E.; Lee, D. Generative Artificial Intelligence, Human Creativity, and Art. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Nexus 2024, 3, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh, A.; Yousof, G.-S. Piet Mondrian, Early Neo-Plastic Compositions, and Six Principles of Neo-Plasticism. Rupkatha J. Interdiscip. Stud. Humanit. 2019, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, M.; Elgammal, A. Art, Creativity, and the Potential of Artificial Intelligence. Arts 2019, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, Y. Study on Artificial Intelligence: The State of the Art and Future Prospects. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 23, 100224. [Google Scholar]

- Samo, A.; Highhouse, S. Artificial Intelligence and Art: Identifying the Aesthetic Judgment Factors That Distinguish Human-and Machine-Generated Artwork. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W.; Jennings, M.W. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version]. Grey Room 2010, 39, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchen, G. Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, W. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Vis. Cult. Exp. Vis. Cult. 2006, 4, 114–137. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S. Digital Images, Photo-Sharing, and Our Shifting Notions of Everyday Aesthetics. J. Vis. Cult. 2008, 7, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, M. Ubiquitous Photography; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S. Photography: A Very Short Introduction; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, J.M. XCIV. Three-Color Photography. In History of Photography; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 639–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.S. Photography and Sociology. Stud. Vis. Commun. 2017, 1, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Greenier, V.; Moodie, I. Photo-Narrative Frames: Using Visuals with Narrative Research in Applied Linguistics. System 2021, 102, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Alonso, B.; Brescó, I. Narratives of Loss: Exploring Grief through Photography. Qual. Stud. 2021, 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart, R.; Ippolito, J. Re-Collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, T. Photography: The Definitive Visual History; Penguin: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Langmann, S.; Pick, D. Photography as an Art-Based Research Method. In Photography as a Social Research Method; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, R.; Valentino, J. Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Ideas, Materials and Processes, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, G. Technical Aspects of Photography. In Foundations of Photography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; Wells, L. Thinking about Photography: Debates, Historically and Now. In Photography; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 11–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.; Noble, A. Phototextualities: Intersections of Photography and Narrative; UNM Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Read, H. Icon and Idea: The Function of Art in the Development of Human Consciousness; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh, A.; Gamache, G. Equilibrium and Rhythm in Piet Mondrian’s Neo-Plastic Compositions. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2018, 5, 1525858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I.H. Piet Mondrian: The Evolution of His Neo-Plastic Aesthetic 1908–1920. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1968. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0104386 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Jeong, K.-H.; Bae, S.-J. A Study on the Formative Elements of Neo-plasticism Applied on Contemporary Fashion. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 9, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, N.J. De Stijl’s Collaborative Ideal: The Colored Abstract Environment, 1916–1926; Yale University: New Haven, CO, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, J.S. Origins, Imitation, Conventions: Representation in the Visual Arts; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deicher, S. Piet Mondrian, 1872–1944: Structures in Space; Taschen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, E.B. A Classic Painting by Piet Mondrian. Bull. Clevel. Mus. Art 1968, 55, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Locher, P.; Overbeeke, K.; Stappers, P.J. Spatial Balance of Color Triads in the Abstract Art of Piet Mondrian. Perception 2005, 34, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, Y.A.; Joosten, J.; Rudenstine, A.Z.; Jansen, H. (Eds.) The iconoclast. In Piet Mondrian: 1872–1944; Bulfinch Press: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada; London, UK, 1994; pp. 313–372. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, M.C. The Aesthetic Point of View. Metaphilosophy 1970, 1, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, M.C. The Definitions of the Arts. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1961, 20, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, M.C. Aesthetics, Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism; Hackett Publishing: Ndianapolis, Indiana, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, M.C. Aesthetics from Classical Greece to the Present; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, M.C. Aesthetic Experience Regained. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1969, 28, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, N. Recent Approaches to Aesthetic Experience. In Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art: The Analytic Tradition, An Anthology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, N. Beyond Aesthetics: Philosophical Essays; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, N. The Philosophy of Motion Pictures-PhilPapers. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/CARTPO-112 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Carroll, N. On Criticism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durà-Vilà, V. Attending to Works of Art for Their Own Sake in Art Evaluation and Analysis: Carroll and Stecker on Aesthetic Experience. Br. J. Aesthet. 2016, 56, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, N. On the Historical Significance and Structure of Monroe Beardsley’s Aesthetics: An Appreciation. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2010, 44, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, H.; Nadal, M. Ten Years of a Model of Aesthetic Appreciation and Aesthetic Judgments: The Aesthetic Episode–Developments and Challenges in Empirical Aesthetics. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitsuwari, J.; Ueda, Y.; Yun, W.; Nomura, M. Does Human–AI Collaboration Lead to More Creative Art? Aesthetic Evaluation of Human-Made and AI-Generated Haiku Poetry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusterman, R. Aesthetic Experience: From Analysis to Eros. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2006, 64, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreen, M. Beardsley’s Aesthetics; Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- LEÓN, M.J.A. Art in Three Dimensions by Carroll, Noël. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2012, 70, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusterman, R. Pragmatist Aesthetics: Living Beauty, Rethinking Art; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant, A. Sensibility and Sense: The Aesthetic Transformation of the Human World; Andrews UK Limited: Luton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Song, W. Exploring the Influence of Object, Subject, and Context on Aesthetic Evaluation through Computational Aesthetics and Neuroaesthetics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruga-Rozdolska, A. Artificial Intelligence as Part of Future Practices in the Architect’s Work: MidJourney Generative Tool as Part of a Process of Creating an Architectural Form. Architectus 2022, 3, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Jain, N.; Kirchenbauer, J.; Goldblum, M.; Geiping, J.; Goldstein, T. Hard Prompts Made Easy: Gradient-Based Discrete Optimization for Prompt Tuning and Discovery. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 51008–51025. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Pan, Z.; Ma, J.; Jie, L.; Mei, Q. A Prompt Log Analysis of Text-to-Image Generation Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 1–5 May 2023; pp. 3892–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenfen, L.; Zimin, Z. Research on Deep Learning-Based Image Semantic Segmentation and Scene Understanding. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenfen, L.; Zimin, Z. Research on Image Style Transfer and Artistic Creation Algorithm Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. Int. J. New Dev. Eng. Soc. 2024, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fort, J.M.; Mateu, L.G. Exploringthe Potential of Artificial Intelligence as a Tool for Architectural Design: A Perception Study Using Gaudí’sworks. Buildings 2023, 13, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.W.; Cherchiglia, L.; Costa, R. Evolving Mondrian-Style Artworks. In Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design; Correia, J., Ciesielski, V., Liapis, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusa, I.M.M.; Yu, Y.; Sovhyra, T. Reflections on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Works of Art. J. Aesthet. Des. Art Manag. 2022, 2, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, T. Algorithms for Graphics and Image Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roddy, S. Creative Machine-Human Collaboration: Toward a Cybernetic Approach to Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques in the Creative Arts. In AI and the Future of Creative Work; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grba, D. Deep Else: A Critical Framework for Ai Art. Digital 2022, 2, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).