The Evolution of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors over the Last 20 Years: A State of the Art Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

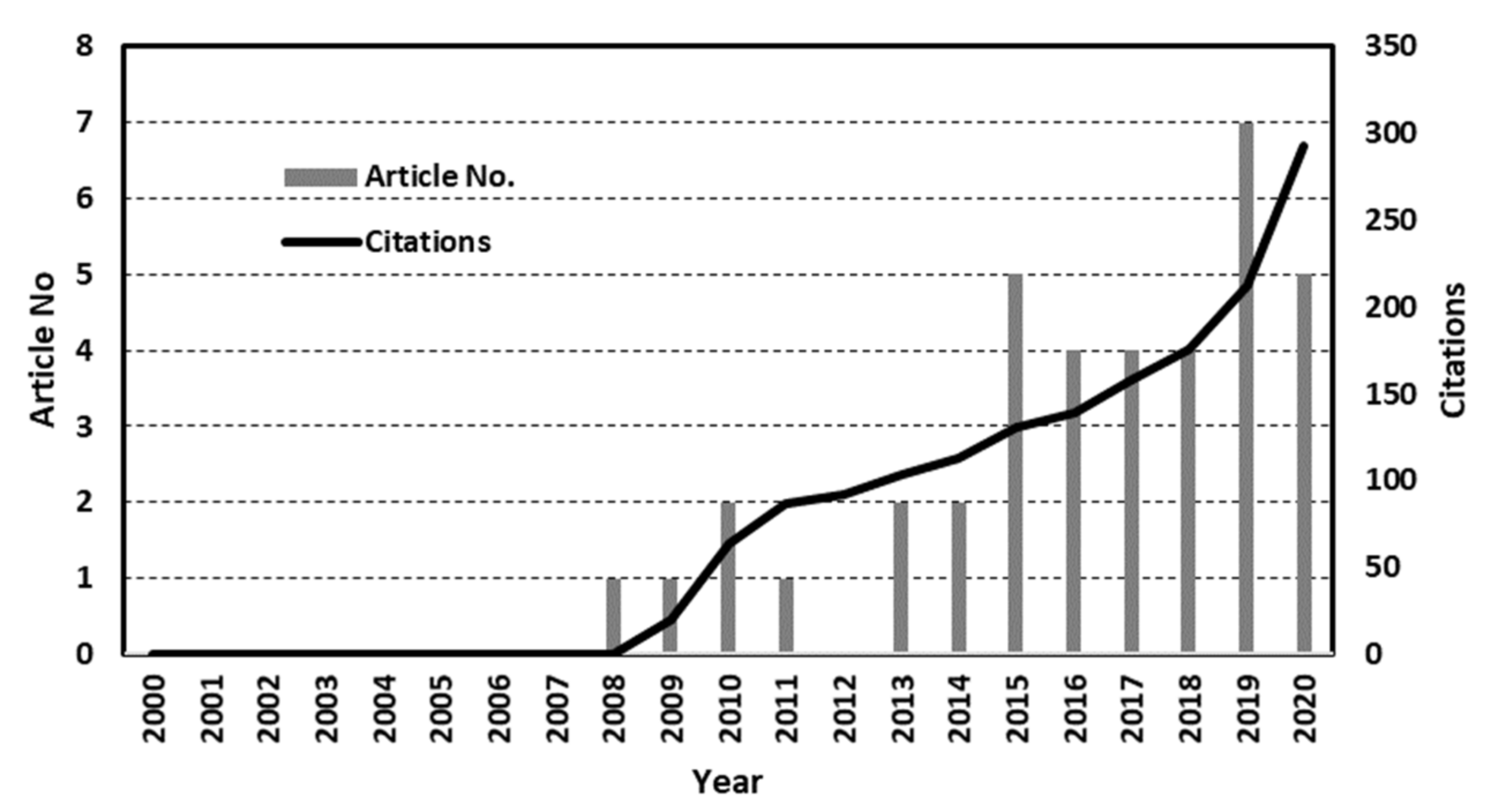

2. General Trend of Evolution of PMRs in the Years from 2000–2020

3. PMRs in Water and Wastewater Treatment

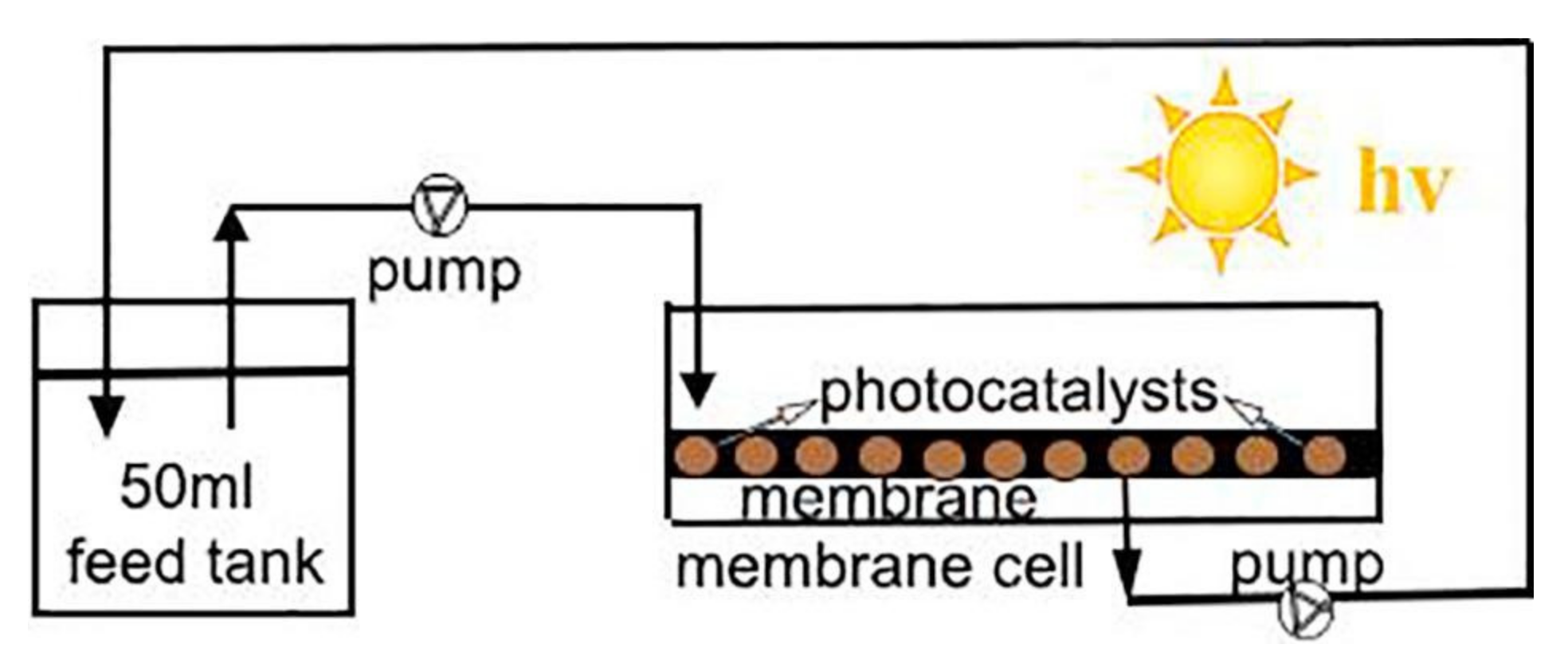

3.1. PMRs Configuration

3.2. Combination of HPC with Other Membrane Processes

3.3. Visible Light as Energy Source

4. Evolution of PMRs in Reaction of Synthesis

4.1. PMRs Configuration in Reactions of Synthesis

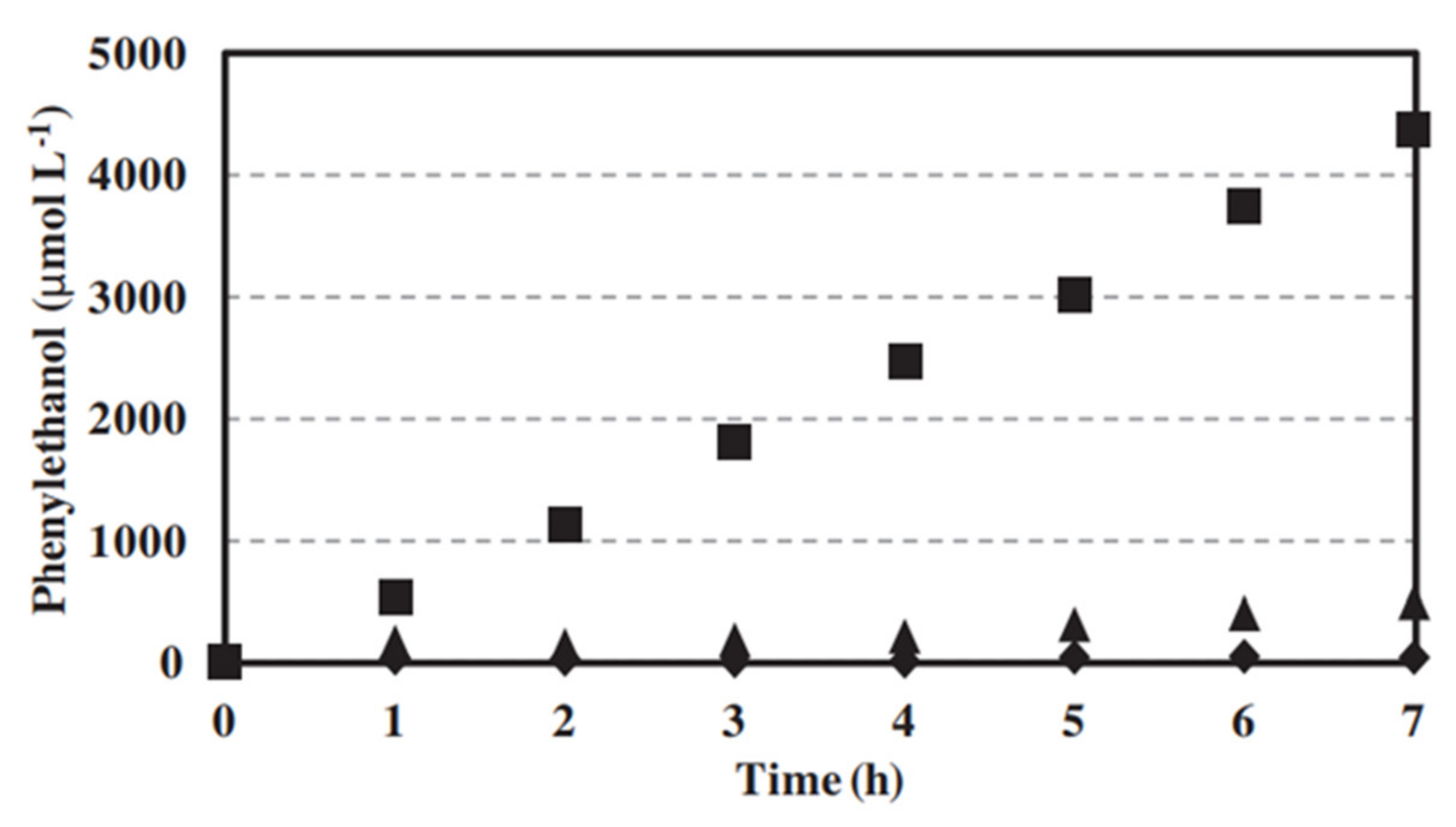

4.1.1. Photocatalyst Immobilized in/on the Membrane in Reactions of Synthesis

4.1.2. CO2 Conversion

4.1.3. Magnetic Materials and Optical Fiber

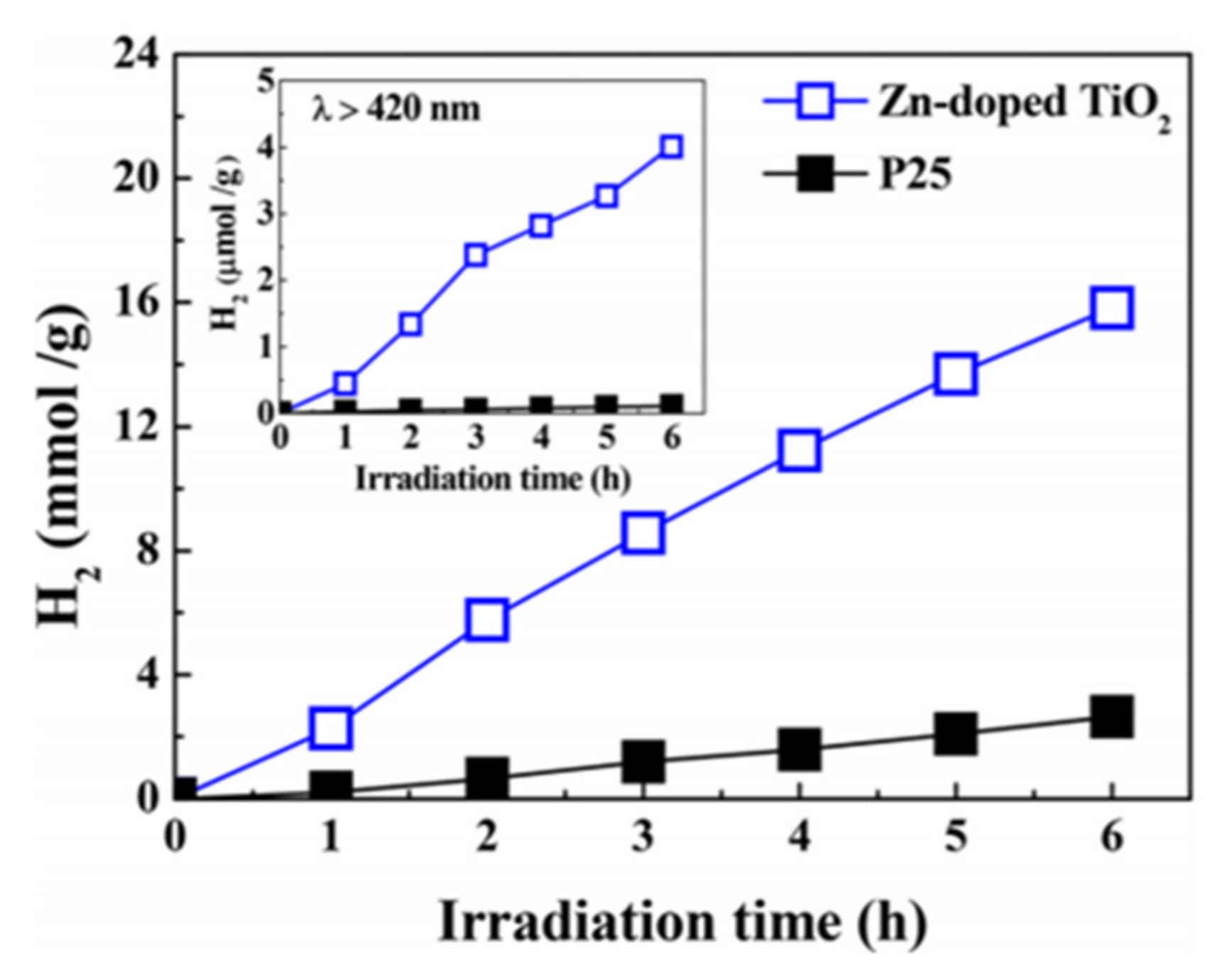

4.2. Visible Light as Energy Source in Reactions of Synthesis

5. Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALD | Atomic layer deposition |

| AOP | Advanced oxidation process |

| AR1 | Acid red 1 |

| AR4 | Acid red 4 |

| AR18 | Acid red 18 |

| Article No. | Article number |

| AY36 | Acid yellow 36 |

| CA | Cellulose acetate |

| CB | Conduction band |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| 4-CP | 4-Chlorophenol |

| CTA | Cellulose triacetate |

| DCF | Diclofenac |

| DCMD | Direct contact membrane distillation |

| DG99 | Direct green 99 |

| DRS | Differential reflectance spectroscopy |

| 2,4-DHBA | 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

| EDS | Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| Eg | Band gap of energy |

| FA | Fulvic acid |

| FE-SEM | Field emission scanning electron microscopy |

| G | Graphene |

| g-C3N4 | Graphite carbon nitride |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| GODs | Graphene quantum dots |

| GO-TiO2 | Graphene oxide doped TiO2 |

| HFM | Hollow fiber membrane |

| HPC | Heterogeneous photocatalysis |

| IBU | Ibuprofen |

| IR | Infrared |

| MB | Methylene blue |

| MD | Membrane distillation |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MOFs | Metal organic frameworks |

| MO | Methyl orange |

| MR | Membrane reactor |

| MS | Membrane separation |

| NAP | Naproxen |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NIR | Near infrared |

| NMP | N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| 4-NP | 4-Nitrophenol |

| NPs | Photocatalyst nanoparticles |

| N-TiO2 | Nitrogen doped TiO2 |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PCA | Picrolonic acid |

| PC | Policarbonate |

| Pd/TiO2 | Palladium doped TiO2 |

| PE | Primary effluent |

| PEBAx | Polyether-polyammide block copolymers |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| PLC | Programmable logic controller |

| PM | Photocatalytic membrane |

| PMR | Photocatalytic membrane reactor |

| PNP | p-nitrophenol |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PR | Photocatalytic reactor |

| PSF | Polysulfone |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PV | Pervaporation |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene difluoride |

| PWF | Pure water flux |

| RO29 | Reactive orange 29 |

| RO | Reverse osmosis |

| SE | Secondary effluent |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SMX | Sulfamethoxazole |

| SPMR | Submerged photocatalytic membrane reactor |

| SPMS | Sono-photocatalysis/membrane separation |

| TMP | Transmembrane pressure |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TW | Tap water |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| UV | Ultraviolet radiation |

| VA | Vanillin |

| VB | Valence band |

| VIS | Visible radiation |

| WOS | Web of science |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. Recent progress of photocatalytic membrane reactors in water treatment and in synthesis of organic compounds. A review. Catal. Today 2017, 281, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.; Augugliaro, V.; Pagliaro, M.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalysis: A promising route for 21st century organic chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2007, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.X.; Fu, C.; Huang, W.X. Surface chemistry of TiO2 connecting thermal catalysis and photocatalysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 9875–9909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, R.; Argurio, P.; Lavorato, C. Review on Reduction and Partial Oxidation of Organics in Photocatalytic (Membrane) Reactors. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 2516–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argurio, P.; Fontananova, E.; Molinari, R.; Drioli, E. Photocatalytic membranes in photocatalytic membrane reactors. Processes 2018, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P.; Szymanski, K.; Darowna, D.; Mozia, S. Overview of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors in Organic Synthesis, Energy Storage and Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2019, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 37–38, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, H. Solar Driven Photocatalysis—An Efficient Method for Removal of Pesticides from Water and Wastewater. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 9071–9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.J.; Chen, J.R.; Yin, Z.L.; Sheng, W.C.; Lin, F.J.; Xu, H.; Cao, S.S. Complete removal of phenolic contaminants from bismuth-modified TiO2 single-crystal photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Thi, L.A.P.; Le, Q.V.; Singh, P.; Raizada, P.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Tailored photocatalysts and revealed reaction pathways for photodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in water, soil and other sources. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.N.; Meng, L.J.; Shi, J.Q.; Li, J.H.; Zhang, X.S.; Feng, M.B. Metal-organic frameworks/carbon-based materials for environmental remediation: A state-of-the-art mini-review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, M.; Claycomb, E.C.; Liu, Y.N.; Alivio, T.E.G.; Banerjee, S.; Chu, K.H. Effectiveness of zinc oxide-assisted photocatalysis for concerned constituents in reclaimed wastewater: 1,4-Dioxane, trihalomethanes, antibiotics, antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodhya, D.; Veerabhadram, G. A review on recent advances in photodegradation of dyes using doped and heterojunction based semiconductor metal sulfide nanostructures for environmental protection. Mater. Today Energy 2018, 9, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H.; Khanuja, M. Hydrothermal in-situ synthesis of MoSe2-polypyrrole nanocomposite for efficient photocatalytic degradation of dyes under dark and visible light irradiation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 254, 117508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, G.H.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J.G.; Fan, J.J. Sulfur-doped g-C3N4/TiO2 S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst for Congo Red photodegradation. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.F.; Ma, S.; Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Shi, Z.; Mu, Y.; Liu, X.M. Construction of donor-acceptor type conjugated microporous polymers: A fascinating strategy for the development of efficient heterogeneous photocatalysts in organic synthesis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, F.; Bellardita, M.; Garcia-Lopez, E.I.; Marci, G.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis for Selective Formation of High-Value-Added Molecules: Some Chemical and Engineering Aspects. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11191–11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, B. Photocatalysis in Organic Synthesis—Past, Present, and Future. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1979–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, M.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M. Selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO mediated by a FeFe -hydrogenase model with a 1,2-phenylene S-to-S bridge. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.Y.; Mao, C.L.; Yang, Z.J.; Zhang, Q.H.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Gu, L.; Zhang, T.R. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction to CO over Ni Single Atoms Supported on Defect-Rich Zirconia. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2002928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Pirri, G.; Poerio, T.; Molinari, R. Pd/TiO2 doped faujasite photocatalysts for acetophenone transfer hydrogenation in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. J. Catal. 2017, 353, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P.; Molinari, R. TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 as Photocatalysts for Hydrogenation of Ketones and Perspective of Membrane Application. Int. J. Adv. Res. Chem. Sci. 2019, 6, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroyuk, O.L.; Kuchmy, S.Y. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Selective Reductive Transformations of Organic Compounds: A Review. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2020, 56, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xu, Z.; Kobayashi, H.; Nakane, K. Novel Pd-loaded urchin-like (NH4)(x)WO3/WO3 as an efficient visible-light-driven photocatalyst for partial conversion of benzyl alcohol. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 845, 156225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Meng, S.G.; Zhang, S.J.; Zheng, X.Z.; Chen, S.F. 2D/2D MXene/g-C3N4 for photocatalytic selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-formylfuran. Catal. Commun. 2020, 147, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.; Bai, G.Y. Engineering donor-acceptor conjugated organic polymers with boron nitride to enhance photocatalytic performance towards visible-light-driven metal-free selective oxidation of sulfides. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 277, 119274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, Z.; Yang, P.J.; Wang, S.B.; Huang, C.J.; Wang, X.C. Hydrogen reduction treatment of boron carbon nitrides for photocatalytic selective oxidation of alcohols. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 276, 118916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, A.; Bellardita, M.; Megna, B.; Parrino, F.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic oxidation of trans-ferulic acid to vanillin on TiO2 and WO3-loaded TiO2 catalysts. Catal. Today 2015, 252, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Caruso, A.; Argurio, P.; Poerio, T. Degradation of the drugs Gemfibrozil and Tamoxifen in pressurized and de-pressurized membrane photoreactors using suspended polycrystalline TiO2 as catalyst. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 319, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Argurio, P.; Szymański, K.; Darowna, D.; Mozia, S. Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors for Wastewater Treatment. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes: Membrane Technology for Water and Wastewater Treatment—Advances and Emerging Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ismael, M. A review on graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) based nanocomposites: Synthesis, categories, and their application in photocatalysis. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 846, 156446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Yao, Y.; Meng, X.C. Recent development on BN-based photocatalysis: A review. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 120, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh-Khaneghah, S.; Habibi-Yangjeh, A. g-C3N4/carbon dot-based nanocomposites serve as efficacious photocatalysts for environmental purification and energy generation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.Y.; Ma, Z.B.; Yang, X.M. Fundamentals of TiO2 Photocatalysis: Concepts, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Park, S.J. An overview of TiO2-based photocatalytic membrane reactors for water and wastewater treatments. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 84, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, A.; Price, W.E.; Hai, F.I. A critical review on advanced oxidation processes for the removal of trace organic contaminants: A voyage from individual to integrated processes. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddo, V.; Augugliaro, V.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic membrane reactors: Case studies and perspectives. Asia Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 4, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo Lumbaque, E.; Sirtori, C.; Vilar, V.J.P. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in synthetic and real matrices using a tube-in-tube membrane reactor with radial addition of H2O2. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 743, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. Visible-Light Photocatalysts and Their Perspectives for Building Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors for Various Liquid Phase Chemical Conversions. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanpour, V.; Darrudi, N.; Sheydaei, M. A comprehensive investigation of effective parameters in continuous submerged photocatalytic membrane reactors by RSM. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2020, 157, 108144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Tran, Q.B.; Nguyen, X.C.; Hai, L.T.; Ho, T.T.T.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Vo, D.V.N.; Lami, S.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Hoang, C.T.; et al. Submerged photocatalytic membrane reactor with suspended and immobilized N-doped TiO2 under visible irradiation for diclofenac removal from wastewater. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 142, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Mozia, S. Editorial catalysts: Special issue on photocatalytic membrane reactors. Catalysts 2020, 10, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, K.P.; Kanmani, S. Progression of Photocatalytic reactors and it’s comparison: A Review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 154, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shen, Z.P.; Shi, L.; Cheng, R.; Yuan, D.H. Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) in water treatment: Configurations and influencing factors. Catalysts 2017, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S. Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) in water and wastewater treatment. A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 73, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, C.; Lotfi, S.; Espindola, J.C.; Fischer, K.; Schulze, A.; Schafer, A.I. Comparison of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactor Types for the Degradation of an Organic Molecule by TiO2-Coated PES Membrane. Catalysts 2020, 10, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, L.; Murgolo, S.; Dzinun, H.; Othman, M.H.D.; Ismail, A.F.; Carballa, M.; Mascolo, G. Application of immobilized TiO2 on PVDF dual layer hollow fibre membrane to improve the photocatalytic removal of pharmaceuticals in different water matrices. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 240, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, R. Photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) for virus removal in water: Performance and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 277, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Choo, K.H. Photocatalytic mineralization of secondary effluent organic matter with mitigating fouling propensity in a submerged membrane photoreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 288, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Darowna, D.; Wróbel, R.; Morawski, A.W. A study on the stability of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 495, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, K.H.; Chang, D.I.; Park, K.W.; Kim, M.H. Use of an integrated photocatalysis/hollow fiber microfiltration system for the removal of trichloroethylene in water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvarega, A.T.; Khumalo, N.; Dlamini, D.; Mamba, B.B. Polysulfone/N,Pd co-doped TiO2 composite membranes for photocatalytic dye degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 191, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, A.L.; Hairom, N.H.H.; Ng, L.Y.; Ng, C.Y.; Ahmad, M.K.; Mohammad, A.W. Industrial textile wastewater treatment via membrane photocatalytic reactor (MPR) in the presence of ZnO-PEG nanoparticles and tight ultrafiltration. J. Water Process. Eng. 2019, 31, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, K.; Morawski, A.W.; Mozia, S. Effectiveness of treatment of secondary effluent from a municipal wastewater treatment plant in a photocatalytic membrane reactor and hybrid UV/H2O2–Ultrafiltration system. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2018, 125, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, G.E.; Athanasekou, C.P.; Katsaros, F.K.; Kanellopoulos, N.K.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Likodimos, V.; Falaras, P. Double-side active TiO2-modified nanofiltration membranes in continuous flow photocatalytic reactors for effective water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 211, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Pirillo, F.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in water by using polycrystalline TiO2 and a nanofiltration membrane reactor. Catal. Today 2006, 118, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, D.; Qiang, Z.M.; Xiao, S.H.; Liu, Q.X.; Lei, Y.Q.; Zhou, T.T. Degradation of Reactive Black 5 in a submerged photocatalytic membrane distillation reactor with microwave electrodeless lamps as light source. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 122, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Tomaszewska, M.; Morawski, A.W. Photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) coupling photocatalysis and membrane distillation—Effectiveness of removal of three azo dyes from water. Catal. Today 2007, 129, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Parrino, F.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. A Dialysis Photocatalytic Reactor for the Green Production of Vanillin. Catalysts 2020, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azrague, K.; Aimar, P.; Benoit-Marquié, F.; Maurette, M.T. A new combination of a membrane and a photocatalytic reactor for the depollution of turbid water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 72, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L.; Parrino, F.; Santarelli, F. Process intensification in a photocatalytic membrane reactor: Analysis of the techniques to integrate reaction and separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 310, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Augugliaro, V.; Cardillo, A.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, G.; Palmisano, L. A pervaporation photocatalytic reactor for the green synthesis of vanillin. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 224, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Augugliaro, V.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. Pervaporation membrane reactors. In Handbook of Membrane Reactors, Vol 2: Reactor Types and Industrial Applications; Basile, A., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 107–151. [Google Scholar]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Santarelli, F. Design of a Pervaporation Photocatalytic Reactor for Process Intensification. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2012, 35, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudita, M.; Bogatu, C.; Enesca, A.; Duta, A. The influence of the additives composition and concentration on the properties of SnOx thin films used in photocatalysis. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 2185–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.M.; Liu, X.M.; Li, F.; Li, T.H.; Zhang, M.; Singh, H.; Huttula, M.; Cao, W. Iodine doped Z-scheme Bi2O2CO3/Bi2WO6 photocatalysts: Facile synthesis, efficient visible light photocatalysis, and photocatalytic mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Wu, X.L.; Mine, S.Y.; Matsuoka, M.; Chu, Y.H.; Wang, Z.M. Crafting carbon sphere-titania core-shell interfacial structure to achieve enhanced visible light photocatalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 534, 147566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, A.N.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.W. Low-temperature in situ fabrication of porous S-doped g-C3N4 nanosheets using gaseous-bubble template for enhanced visible-light photocatalysis. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28481–28489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, T.H.T.; Thi, C.M.; Viet, P.V. Enhancing photocatalysis of NO gas degradation over g-C3N4 modified alpha-Bi2O3 microrods composites under visible light. Mater. Lett. 2020, 281, 128637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Anderson, W.A.; Tanvir, S.; Kansal, S.K. Solar light active silver/iron oxide/zinc oxide heterostructure for photodegradation of ciprofloxacin, transformation products and antibacterial activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 557, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.M.; Ren, T.J.; Zhao, W.Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.X.; Xu, Y. Preparation of Zn2GeO4 nanosheets with MIL-125(Ti) hybrid photocatalyst for improved photodegradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 133, 111013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beissenov, R.E.; Mereke, A.L.; Umirzakov, A.G.; Mansurov, Z.A.; Rakhmetov, B.A.; Beisenova, Y.Y.; Shaikenova, A.A.; Muratov, D.A. Fabrication of 3D porous CoTiO3 photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution application: Preparation and properties study. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 121, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Chen, X.T.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.A.; Liao, L.X.; Li, B. Cuprous oxide/titanium dioxide composite photocatalytic decolorization of reactive brilliant red X-3B dyes wastewater under visible light. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 5459–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.B.; Buttiglieri, G.; Babic, S. State-of-the-art and current challenges for TiO2/UV-LED photocatalytic degradation of emerging organic micropollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.C.; Fernandes, J.R.; Rodriguez-Chueca, J.; Peres, J.A.; Lucas, M.S.; Tavares, P.B. Photocatalytic degradation of an agro-industrial wastewater model compound using a UV LEDs system: Kinetic study. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, G.; Anderson, M.; Read, H.; Esplugas, S. A Jacketed Annular Membrane Photocatalytic Reactor for Waste-Water Treatment—Degradation of Formic-Acid and Atrazine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1993, 71, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzweiler, R.J.; Mowery, D.L.; Wagg, L.M.; Dong, J.J. Pilot Scale Investigation of Photocatalytic Detoxification of BETX Water. In Proceedings of the ASME-JSES-JSME International Solar Energy Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–30 March 1994; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sopajaree, K.; Qasim, S.A.; Basak, S.; Rajeshwar, K. Integrated flow reactor-membrane filtration system for heterogeneous photocatalysis. Part, I. Experiments and modelling of a batch-recirculated photoreactor. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1999, 29, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopajaree, K.; Qasim, S.A.; Basak, S.; Rajeshwar, K. An integrated flow reactor-membrane filtration system for heterogeneous photocatalysis. Part II: Experiments on the ultrafiltration unit and combined operation. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1999, 29, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Zhao, Y.G. Advanced treatment of dyeing wastewater for reuse. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 39, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, V.; Litter, M.; Palmisano, L.; Soria, J. The combination of heterogeneous photocatalysis with chemical and physical operations: A tool for improving the photoprocess performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2006, 7, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Y.T.; Xu, S.S.; Li, Z.H.; An, X.H.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Shiang, F.Q. Progress of applied research on TiO2 photocatalysis-membrane separation coupling technology in water and wastewater treatments. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Argurio, P.; Bellardita, M.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic Processes in Membrane Reactors. In Membrane Science and Engineering; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Fontananova, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 101–138. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, R.; Mungari, M.; Drioli, E.; Di Paola, A.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L.; Schiavello, M. Study on a photocatalytic membrane reactor for water purification. Catal. Today 2000, 55, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Scicchitano, G.; Pirillo, F.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. Preparation, characterisation and testing of photocatalytic polymeric membranes with entrapped or suspended TiO2. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 23, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodar, R.A.; You, S.J.; Chou, H.H. Study the self cleaning, antibacterial and photocatalytic properties of TiO2 entrapped PVDF membranes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, C.; Liu, J.; Shen, X.; Tong, H. Development of mesoporous titanium dioxide hybrid poly(vinylidene fluoride) ultrafiltration membranes with photocatalytic properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artale, M.A.; Augugliaro, V.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G.; Grande, C.; Loddo, V.; Molinari, R.; Palmisano, L.; Schiavello, M. Preparation and characterisation of membranes with entrapped TIO2 and preliminary photocatalytic tests. Ann. Chim. 2001, 91, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Modise, S.J.; Breet, E.L.J.; Keizer, K. Photocatalytic degradation of phenol on TiO2 coated inorganic membranes. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2000, 53, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, P.; Fan, Y.; Xu, N.; Shi, J. Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic activity of TiO2 membrane photocatalyst immobilized on active carbon. Chin. J. Catal. 2000, 21, 496. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Stathatos, E.; Dionysiou, D.D. Sol-gel preparation of mesoporous photocatalytic TiO2 films and TiO2Al2O3composite membranes for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2006, 63, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Quan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, H. Integration of separation and photocatalysis using an inorganic membrane modified with Si-doped TiO2 for water purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 335, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacres, R.; Ikeda, S.; Torimoto, T.; Ohtani, B. Development of a novel photocatalytic reaction system for oxidative decomposition of volatile organic compounds in water with enhanced aeration. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2003, 160, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, F.; Xing, Y.; Xian, C.J.; Guo, B.W. Photocatalytic degradation of low level formaldehyde on TiO2 porous film. Huanjing Kexue Environ. Sci. 2005, 26, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.F.; Zheng, G.H.; Yang, F.L. MWNTs/TiO2 composite functional membranes and their adsorption properties. Zhongguo Huanjing Kexue/China Environ. Sci. 2009, 29, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Xu, S.; Luo, S.; Cai, Q. Photocatalytic activities of C-N-doped TiO2 nanotube array/carbon nanorod composite. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 1748–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, S.; Guan, W.; Yao, Y.; Tang, P.; Li, C. Visible light driven photodynamic anticancer activity of graphene oxide/TiO2 hybrid. Carbon 2012, 50, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosc, F.; Ayral, A.; Guizard, C. Mesoporous anatase coatings for coupling membrane separation and photocatalyzed reactions. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 265, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinun, H.; Othman, M.H.D.; Ismail, A.F.; Puteh, M.H.; Rahman, M.A.; Jaafar, J. Stability study of PVDF/TiO2 dual layer hollow fibre membranes under long-term UV irradiation exposure. J. Water Process. Eng. 2017, 15, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, S.S.; Harun, Z.; Abd Latif, I.S. Characterization and performance of porous photocatalytic ceramic membranes coated with TiO2 via different dip-coating routes. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 11534–11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Irawan, A.; Ku, Y. Photocatalytic degradation of Acid Red 4 using a titanium dioxide membrane supported on a porous ceramic tube. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4725–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, S.S.; Chiang, K.; Fane, A.G. The stability of polymeric membranes in a TiO2 photocatalysis process. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 275, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissen, S.U.; Xi, W.; Weidemeyer, A.; Vogelpohl, A.; Bousselmi, L.; Ghrabi, A.; Ennabli, A. Comparison of suspended and fixed photocatalytic reactor systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2001, 44, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Palmisano, L.; Drioli, E.; Schiavello, M. Studies on various reactor configurations for coupling photocatalysis and membrane processes in water purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 206, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Pirillo, F.; Falco, M.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic degradation of dyes by using a membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2004, 43, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markowska-Szczupak, A.; Rokicka, P.; Wang, K.L.; Endo, M.; Morawski, A.W.; Kowalska, E. Photocatalytic Water Disinfection under Solar Irradiation by D-Glucose-Modified Titania. Catalysts 2018, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damodar, R.A.; You, S.J.; Ou, S.H. Coupling of membrane separation with photocatalytic slurry reactor for advanced dye wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 76, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairom, N.H.H.; Mohammad, A.W.; Kadhum, A.A.H. Effect of various zinc oxide nanoparticles in membrane photocatalytic reactor for Congo red dye treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 137, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rani, C.N.; Karthikeyan, S. Performance of an indigenous integrated slurry photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) on the removal of aqueous phenanthrene (PHE). Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 2642–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.X.; Ding, L.H.; Luo, J.Q.; Jaffrin, M.Y.; Tang, B. Membrane fouling in photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) for water and wastewater treatment: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Darowna, D.; Orecki, A.; Wrobel, R.; Wilpiszewska, K.; Morawski, A.W. Microscopic studies on TiO2 fouling of MF/UF polyethersulfone membranes in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 470, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Qu, F.S.; Liang, H.; Li, K.; Bai, L.M.; Li, G.B. Control of submerged hollow fiber membrane fouling caused by fine particles in photocatalytic membrane reactors using bubbly flow: Shear stress and particle forces analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 172, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Szymanski, K.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Tryba, B.; Toyoda, M.; Morawski, A.W. Effect of process parameters on fouling and stability of MF/UF TiO2 membranes in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 142, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ji, M.; Wang, Z.; Jin, L.; An, D. A new submerged membrane photocatalysis reactor (SMPR) for fulvic acid removal using a nano-structured photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 131, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertèsz, S.; Cakl, J.; Jiránková, H. Submerged hollow fiber microfiltration as a part of hybrid photocatalytic process for dye wastewater treatment. Desalination 2014, 343, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, P.; Xu, P.; Hu, L.; Wang, X.; Qu, J.; Zhang, G. Submerged membrane photocatalytic reactor for advanced treatment of p-nitrophenol wastewater through visible-light-driven photo-Fenton reactions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.C.; Huertas, R.M.; Crespo, J.G.; Pereira, V.J. Novel submerged photocatalytic membrane reactor for treatment of olive mill wastewaters. Catalysts 2019, 9, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Kong, H.; Li, P.; Shao, J.; He, Y. Photo-Fenton degradation of amoxicillin via magnetic TiO2-graphene oxide-Fe3O4 composite with a submerged magnetic separation membrane photocatalytic reactor (SMSMPR). J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Choo, K.H. Submerged microfiltration-catalysis hybrid reactor treatment: Photocatalytic inactivation of bacteria in secondary wastewater effluent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 198, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

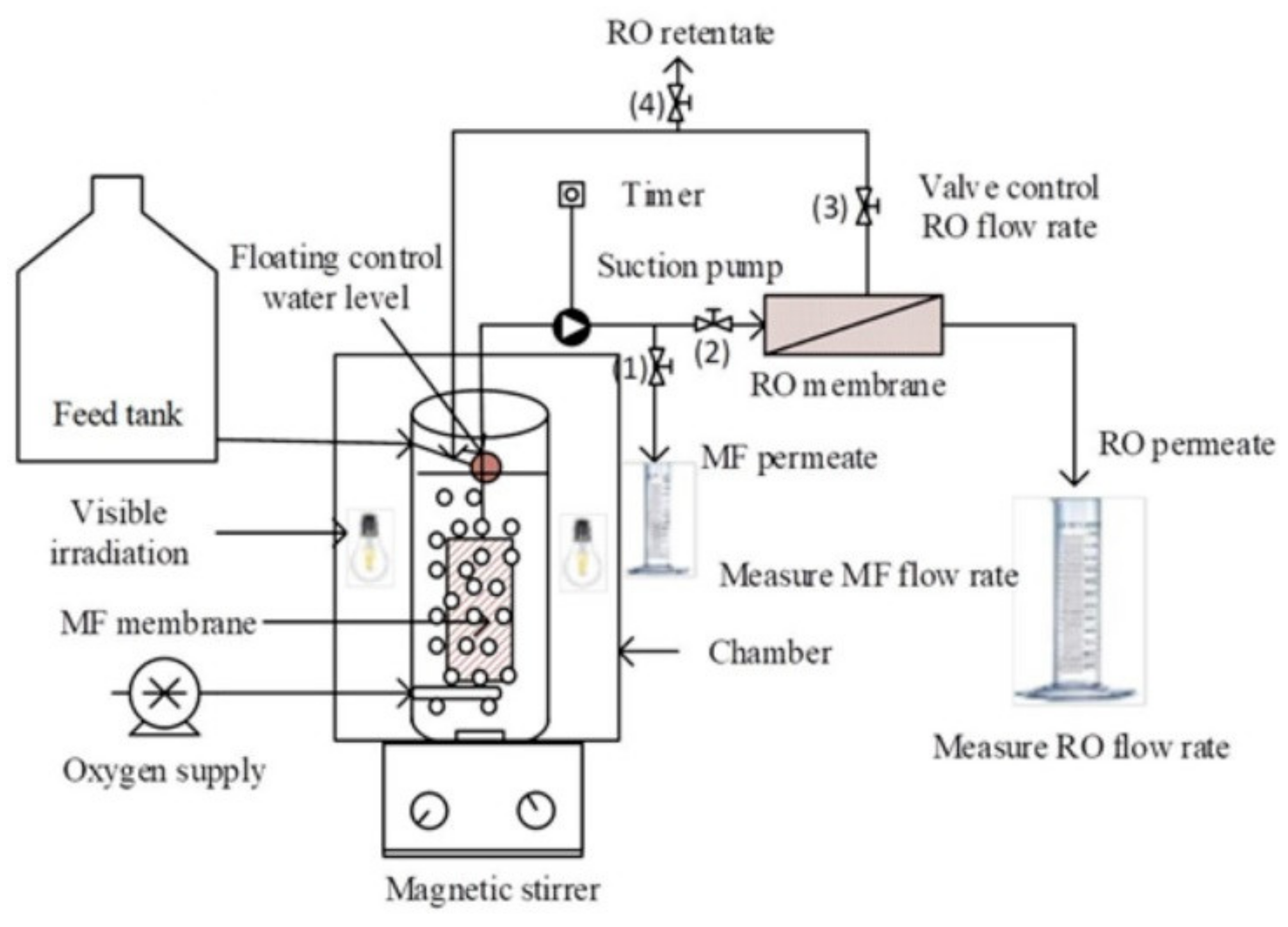

- Tung, T.V.; Ananpattarachai, J.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Diclofenac removal by submerged MF membrane photocatalytic reactor and coupling with RO membrane. Lowl. Technol. Int. 2018, 20, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Vatanpour, V.; Karami, A.; Sheydaei, M. Central composite design optimization of Rhodamine B degradation using TiO2 nanoparticles/UV/PVDF process in continuous submerged membrane photoreactor. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2017, 116, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, N.N.M.; Jaafar, J.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Aziz, F.; Yusof, N.; Salleh, W.N.; Ismail, A.F. Titanium dioxide hollow nanofibers for enhanced photocatalytic activities. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 2004–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tong, H.; Pei, W.; Liu, W.; Shi, F.; Li, Y.; Huo, Y. Integrated photocatalysis-adsorption-membrane separation in rotating reactor for synergistic removal of RhB. Chemosphere 2021, 270, 129424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ramachandran, S.K.; Gumpu, M.B.; Zsuzsanna, L.; Veréb, G.; Kertész, S.; Gangasalam, A. Titanium dioxide doped hydroxyapatite incorporated photocatalytic membranes for the degradation of chloramphenicol antibiotic in water. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Tomaszewska, M.; Morawski, A.W. A new photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) for removal of azo-dye Acid Red 18 from water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2005, 59, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Morawski, A.W. Hybridization of photocatalysis and membrane distillation for purification of wastewater. Catal. Today 2006, 118, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Tomaszewska, M.; Morawski, A.W. Removal of azo-dye Acid Red 18 in two hybrid membrane systems employing a photodegradation process. Desalination 2006, 198, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Toyoda, M.; Inagaki, M.; Tryba, B.; Morawski, A.W. Application of carbon-coated TiO2 for decomposition of methylene blue in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 140, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Toyoda, M.; Tsumura, T.; Inagaki, M.; Morawski, A.W. Comparison of effectiveness of methylene blue decomposition using pristine and carbon-coated TiO2 in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. Desalination 2007, 212, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Morawski, A.W.; Toyoda, M.; Inagaki, M. Effectiveness of photodecomposition of an azo dye on a novel anatase-phase TiO2 and two commercial photocatalysts in a photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S.; Morawski, A.W. Integration of photocatalysis with ultrafiltration or membrane distillation for removal of azo dye direct green 99 from water. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2009, 12, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darowna, D.; Grondzewska, S.; Morawski, A.W.; Mozia, S. Removal of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs from primary and secondary effluents in a photocatalytic membrane reactor. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, H.J.; Yang, G.X.; Liu, W.H.; Huo, Y.N.; Xie, Z.L.; Li, H.X. Coupling system of Ag/BiOBr photocatalysis and direct contact membrane distillation for complete purification of N-containing dye wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Santarelli, F. Intensification of water detoxification by integrating photocatalysis and pervaporation. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 2007, 129, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Zhang, X.T.; Tryk, D.A. TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, O.; Huisman, C.L.; Reller, A. Photoinduced reactivity of titanium dioxide. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2004, 32, 33–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Green, M.; Just, M.; Li, Y.Y.; Chen, X.B. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials for photocatalysis. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 193003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, K.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2012, 13, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiam, S.L.; Pung, S.Y.; Yeoh, F.Y. Recent developments in MnO2-based photocatalysts for organic dye removal: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 5759–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetchakun, K.; Wetchakun, N.; Sakulsermsuk, S. An overview of solar/visible light-driven heterogeneous photocatalysis for water purification: TiO2- and ZnO-based photocatalysts used in suspension photoreactors. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratova, M.; Redfern, J.; Verran, J.; Kelly, P.J. Highly efficient photocatalytic bismuth oxide coatings and their antimicrobial properties under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 239, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasekou, C.P.; Moustakas, N.G.; Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martinez, L.M.; Figueiredob, J.L.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, A.M.T.; Dona-Rodriguez, J.M.; Romanos, G.E.M.; Falaras, P. Ceramic photocatalytic membranes for water filtration under UV and visible light. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 178, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horovitz, I.; Avisar, D.; Baker, M.A.; Grilli, R.; Lozzi, L.; Di Camillo, D.; Mamane, H. Carbamazepine degradation using a N-doped TiO2 coated photocatalytic membrane reactor: Influence of physical parameters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 310, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, B.; Chen, W.P.; Liu, J.D.; An, J.J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Sillanpaa, M. Continuous removal of tetracycline in a photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) with ZnIn2S4 as adsorption and photocatalytic coating layer on PVDF membrane. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 364, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Tsumura, T.; Kinumoto, T.; Toyoda, M. Graphitic carbon nitrides (g-C3N4) with comparative discussion to carbon materials. Carbon 2019, 141, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Cui, J.; Kuang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, W. Ti3+-TiO2/g-C3N4 mesostructured nanosheets heterojunctions as efficient visible-light-driven photocatalysts. J. Catal. 2018, 357, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Sun, F.Q.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y. Novel mpg-C3N4/TiO2 nanocomposite photocatalytic membrane reactor for sulfamethoxazole photodegradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Tran, Q.B.; Ly, Q.V.; Hai, L.; Le, D.T.; Tran, M.B.; Tam Ho, T.T.; Nguyen, X.C.; Shokouhimehrh, M.; Vo, D.-V.N.; et al. Enhanced visible photocatalytic degradation of diclofen over N-doped TiO2 assisted with H2O2: A kinetic and pathway study. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8361–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, M.; Fattahi, M.; Ghalamchi, L.; Vatanpour, V. Systematic comparison of sono-synthesized Ce-, La- and Ho-doped ZnO nanoparticles and using the optimum catalyst in a visible light assisted continuous sono-photocatalytic membrane reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 56, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.N.; Xie, Z.L.; Wang, X.D.; Li, H.X.; Hoang, M.; Caruso, R.A. Methyl orange removal by combined visible-light photocatalysis and membrane distillation. Dye. Pigment. 2013, 98, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropietro, T.F.; Meringolo, C.; Poerio, T.; Scarpelli, F.; Godbert, N.; Di Profio, G.; Fontananova, E. Multistimuli Activation of TiO2 α-alumina membranes for degradation of methylene blue. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 11049–11057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Sanchez, M.; Lavorato, C.; Puche, M.; Fornes, V.; Molinari, R.; Garcia, H. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation by Using Dye-Sensitized Graphene Oxide as a Photocatalyst. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16774–16783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, C.; Primo, A.; Molinari, R.; Garcia, H. N-Doped Graphene Derived from Biomass as a Visible-Light Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Generation from Water/Methanol Mixtures. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, X.; Shao, L.; Zeng, H. Super hydrophilic composite membrane with photocatalytic degradation and self-cleaning ability based on LDH and g-C3N4. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, G. Synthesis of a hydrophilic alpha-sulfur/PDA composite as a metal-free photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2017, 54, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, S.; Ananthakrishnan, R. Metal-free-photocatalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol by resin-supported dye under the visible irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2011, 105, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.; Garcia-Lopez, E.; Marci, G.; Loddo, V.; Yurdakal, S.; Augugliaro, V.; Palmisano, L. Advances in selective conversions by heterogeneous photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7074–7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Poerio, T.; Argurio, P. One-step production of phenol by selective oxidation of benzene in a biphasic system. Catal. Today 2006, 118, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Caruso, A.; Poerio, T. Direct benzene conversion to phenol in a hybrid photocatalytic membrane reactor. Catal. Today 2009, 144, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. Photocatalytic reduction of acetophenone in membrane reactors under UV and visible light using TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 274, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-R.; Dizon, G.V.C.; Yamada, K.; Liu, C.-Y.; Venault, A.; Lin, H.-Y.; Yoshida, M.; Hu, C. Sulfur-doped g-C3N4 nanosheets for photocatalysis: Z-scheme water splitting and decreased biofouling. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 567, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrollahi, N.; Ghalamchi, L.; Vatanpour, V.; Khataee, A. Photocatalytic-membrane technology: A critical review for membrane fouling mitigation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 93, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, V.; Camera-Roda, G.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, G.; Palmisano, L.; Parrino, F.; Puma, M.A. Synthesis of vanillin in water by TiO2 photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 111, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Cardillo, A.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L.; Parrino, F. Improvement of membrane performances to enhance the yield of vanillin in a pervaporation reactor. Membranes 2014, 4, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koe, W.S.; Lee, J.W.; Chong, W.C.; Pang, Y.L.; Sim, L.C. An overview of photocatalytic degradation: Photocatalysts, mechanisms, and development of photocatalytic membrane. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2522–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Said, K.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Karim, Z.A.; Abdullah, M.S.; Usman, J.; Raji, Y.O. Innovation in membrane fabrication: Magnetic induced photocatalytic membrane. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 113, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.J.; Hu, Y.; Yu, M.J.; Lian, C.; Gao, M.X.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.W.; Wang, S.B. Nitrogen-doped carbon encapsulating molybdenum carbide and nickel nanostructures loaded with PVDF membrane for hexavalent chromium reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 344, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atienzar, P.; Primo, A.; Lavorato, C.; Molinari, R.; Garcia, H. Preparation of Graphene Quantum Dots from Pyrolyzed Alginate. Langmuir 2013, 29, 6141–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jian, X.; Yang, H.M.; Song, X.L.; Liang, Z.H. A photocatalytic graphene quantum dots-Cu2O/bipolar membrane as a separator for water splitting. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3075–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, P.; Wen, P.; Wang, H.; Xu, G.; Han, Y. C-doped Cr2O3/NaY composite membrane supported on stainless steel mesh with enhanced photocatalytic activity for cyclohexane oxidation. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 6552–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Mtz-Enriquez, A.I.; Garcia, C.R.; Coutino-Gonzalez, E.; Oliva, A.I.; Vallejo, M.A.; Cordova, T.; Gomez-Solis, C.; Oliva, J. Efficient hydrogen generation by ZnAl2O4 nanoparticles embedded on a flexible graphene composite. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniamer, M.; Aroujalian, A.; Sharifnia, S. Photocatalytic membrane reactor for simultaneous separation and photoreduction of CO2 to methanol. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, R.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; He, X.; Li, S.; Li, L. Optofluidic membrane microreactor for photocatalytic reduction of CO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 2457–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, J.W.; Schütz, J.A.; Grundy, L.; Des Ligneris, E.; Yi, Z.; Kong, L.; Pozo-Gonzalo, C.; Ionescu, M.; Dumée, L.F. Inorganic Nanoparticles/Metal Organic Framework Hybrid Membrane Reactors for Efficient Photocatalytic Conversion of CO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 35010–35017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, A.; Pomilla, F.R.; Marci, G.; Garcia-Lopez, E.I.; Fontananova, E.; Palmisano, L.; Barbieri, G. CO2 reduction by C3N4-TiO2 Nafion photocatalytic membrane reactor as a promising environmental pathway to solar fuels. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.B.; Yuan, X.Z.; Zeng, G.M.; Wu, Z.B.; Liang, J.; Chen, X.H.; Leng, L.J.; Wang, H. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible-light photocatalytic degradation of refractory pollutant. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 221, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, L.B.; Wei, Y.Y.; Xue, J.; Chen, H.; Ding, L.; Caro, J.; Wang, H.H. Water Transport with Ultralow Friction through Partially Exfoliated g-C3N4 Nanosheet Membranes with Self-Supporting Spacers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8974–8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomilla, F.R.; Brunetti, A.; Marci, G.; Garcia-Lopez, E.I.; Fontananova, E.; Palmisano, L.; Barbieri, G. CO2 to Liquid Fuels: Photocatalytic Conversion in a Continuous Membrane Reactor. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 8743–8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanourakis, S.K.; Pena-Bahamonde, J.; Bandara, P.C.; Rodrigues, D.F. Nano-based adsorbent and photocatalyst use for pharmaceutical contaminant removal during indirect potable water reuse. Npj Clean Water 2020, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.-V.; Wu, J.C.S. Photoreduction of CO2 to fuels under sunlight using optical-fiber reactor. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, R.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; An, L.; Ye, D.; He, X.; Li, S.; Li, L. An optofluidic planar microreactor for photocatalytic reduction of CO2 in alkaline environment. Energy 2017, 120, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; An, L.; Ye, D.; He, X.; Wang, Z. High-performance optofluidic membrane microreactor with a mesoporous CdS/TiO2 SBA-15@carbon paper composite membrane for the CO2 photoreduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 316, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, J.H.; Wen, F.Y.; Li, C. A visible-light-driven transfer hydrogenation on CdS nanoparticles combined with iridium complexes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7080–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.J.; Xu, G.R.; Zhang, B.H.; Gong, J.R. High selectivity in visible-light-driven partial photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol into benzaldehyde over single-crystalline rutile TiO2 nanorods. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 115, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Liu, W.S.; Wang, C.C.; Perng, T.P. Photocatalysis and Hydrogen Evolution of Al- and Zn-Doped TiO2 Nanotubes Fabricated by Atomic Layer Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 33287–33295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.A.; Chen, C.C.; Ma, W.H.; Zhao, J.C. Visible-Light-Induced Aerobic Oxidation of Alcohols in a Coupled Photocatalytic System of Dye-Sensitized TiO2 and TEMPO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9730–9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, P.; Xu, G.; Ma, D.; Qiu, P. NH2-MIL-125(Ti)/TiO2 composites as superior visible-light photocatalysts for selective oxidation of cyclohexane. Mol. Catal. 2018, 452, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, R.; Li, J.; Gao, S.; Cao, R. CdS/NH2-UiO-66 hybrid membrane reactors for the efficient photocatalytic conversion of CO2. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 20152–20160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PMR Configuration | Support | Photocatalyst | Pollutant | Main Results | Ref. Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photocatalyst immobilized on the membrane | 11 commercial polymeric membranes | TiO2 P25 | 4-nitrophenol | 50% photodegradation after 5 h with immobilized photocatalyst 80% photodegradation with suspended photocatalyst | [84] 2000 |

| Three integrative-type PMRs vs. a split type PMR | 11 commercial polymeric membranes | TiO2 P25 | 4-nitrophenol | Split-type configuration appeared to be the most promising for industrial applications: PMR optimization can be obtained by sizing separately the “photoreactor” and the “membrane cell”. Limits: membrane fouling and light scattering by photocatalyst particle | [104] 2002 |

| Suspended vs. entrapped TiO2 | NTR7410 membrane vs. home prepared photocatalytic membrane | TiO2 P25 | Congo red Patent Blue | Slurry PMR was significantly more efficient than the PMR with entrapped photocatalyst. Solutions with high concentration of dyes can be treated by a continuous process obtaining good permeate fluxes and quality. Limit: membrane fouling | [103] 2004 |

| Photocatalyst entrapped in the membrane | Cellulose triacetate (CTA) and polysulfone (PSF) membranes | TiO2 P25 | Congo red | TiO2 was always more efficient when used in suspension | [85] 2005 |

| Slurry integrative-type PMR | 10 polymeric membranes | TiO2 | - | polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), hydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) membranes showed the greatest stability. Limits: membrane fouling and light scattering by photocatalyst particle. | [102] 2006 |

| Submerged PMR air bubbling | Submerged hollow fiber module | nanostructured TiO2/silica gel | Fulvic acid | Effective reduction in membrane fouling. Photocatalyst concentration and air flow significantly affect system performance | [114] 2006 |

| Photocatalyst coated on the membrane | Porous ceramic tube | TiO2 | Acid Red 4 | Photodegradation obtained with the dead-end system was three/five times higher than cross-flow system. Increasing photodegradation with increasing catalyst loading and light intensity, to a catalyst loading limiting value. | [101] 2008 |

| Submerged PMR air bubbling and membrane back-flushing | Submerged hollow fiber membrane (HFM) module | TiO2 | Acid Red 1 (AR1) | Simultaneous AR1 degradation and complete photocatalyst recovery. Air bubbling was effective in controlling membrane fouling. Critical permeate flux 40 L m−2 h−1. Flux < 40 L m−2 h−1 gave reversible fouling, easily removed by membrane back-flushing with the permeate, Flux > 40 L m−2 h−1 gave irreversible fouling. The control of membrane fouling depends mainly by membrane back-flushing parameters, i.e., frequency, duration and intensity. | [115] 2014 |

| Submerged PMR air bubbling and membrane back-flushing | Flat-sheet PVDF membrane | TiO2 P25 | Virus bacteriophage f2 | Filtration flux and permeation mode (continuous or intermittent), significantly affect system performance. Best operating conditions: intermittent suction mode, filtration flux of 40 L m−2 h−1, 99.99% virus inactivation, good control of membrane fouling. Above the “critical” value of the filtration flux, irreversible fouling was observed. | [48] 2015 |

| Photocatalyst entrapped in the membrane | Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) | TiO2 | - | Limited membrane stability: the tensile strength of the TiO2/PVDF membranes decreased after 30 days of UV irradiation | [99] 2017 |

| Photocatalyst coated on the membrane | Kaolin powder | TiO2 nanoparticles | Humic acids | 98.6% photodegradation good antifouling self-cleaning performance good membrane photostability | [100] 2018 |

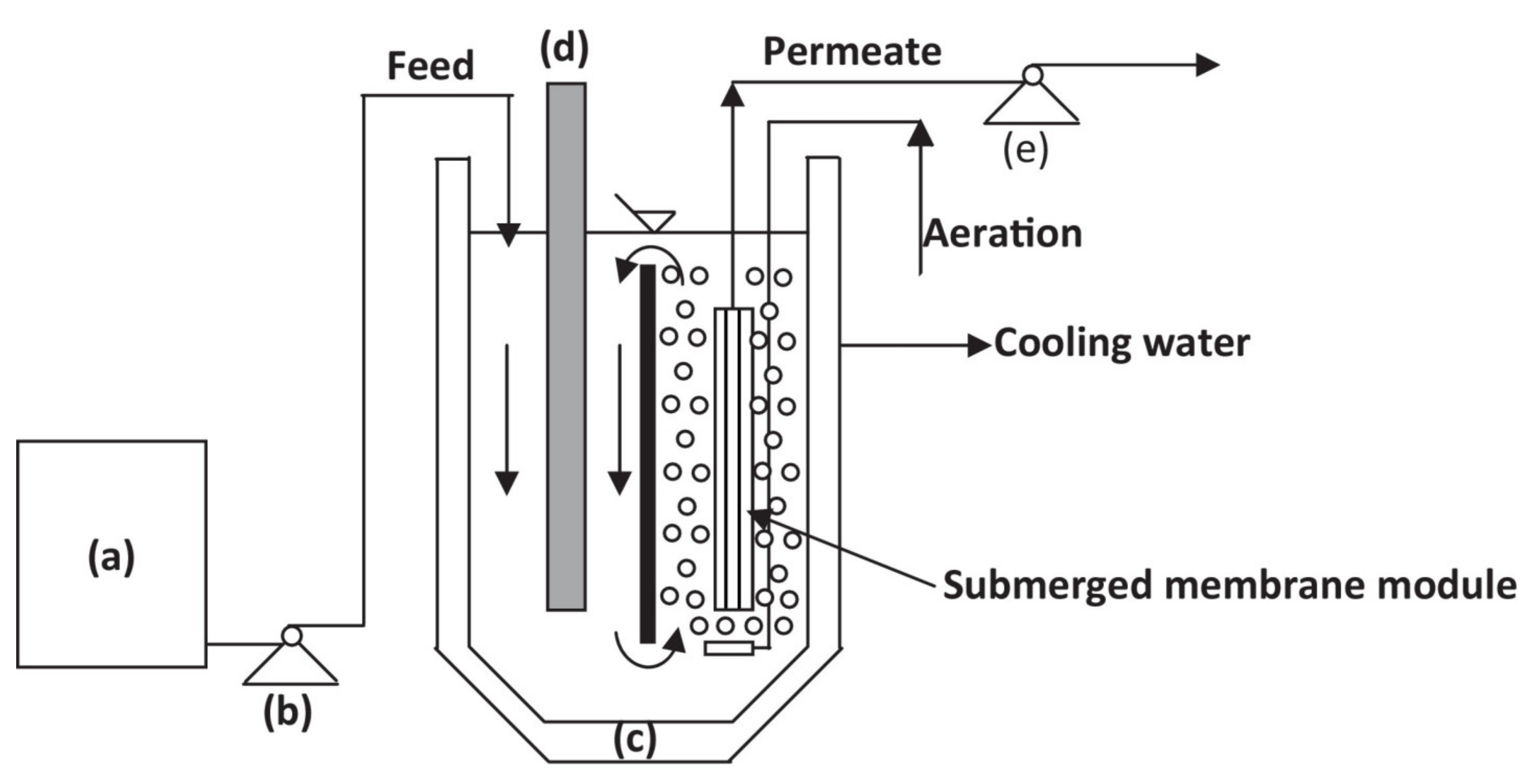

| Submerged PMR with suspended and immobilized photocatalyst and air bubbling | MF ceramic membrane | N–TiO2 | Diclofenac | SPMR with suspended catalyst showed better DCF removal. SPMRs with suspended and immobilized N–TiO2 have both advantages and disadvantages. Advantage of slurry-SPMR: the reaction rate can be enhanced by increasing the photocatalyst. Disadvantage of slurry-SPMR: higher membrane fouling. | [41] 2020 |

| SPMR | Hollow fiber microfiltration (MF) membrane module | Fe(III)-ZnS/g-C3N4 photo-Fenton catalyst | p-nitrophenol (PNP) | 91.6% PNP under simulated solar light irradiation, 10 mg L−1 PNP concentration in the feed, initial pH 5, catalyst dosage 1.0 g L−1, H2O2 concentration 170 mg L−1, aeration rate 0.50 m3 h−1, 4 h of irradiation. The photocatalyst was completely rejected by the MF membrane. | [116] 2021 |

| Hollow titanium dioxide nanofibers (HTNF) | Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofibers | TiO2 | Bisphenol A (BPA) | photocatalytic degradation of BPA 97.3% | [122] 2021 |

| Integrated photocatalysis-adsorption-membrane separation in a rotating reactor | GO | Ag@BiOBr | RhB | The rejection rate of RhB in the case of Ag@BiOBr/AC/GO membrane was always maintained up to about 100% | [123] 2021 |

| Low-pressure cross-flow lab-scale photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) | Polysulfone (PSf) membranes | TiO2-HAP | Chloramphenicol (CAP) | Degradation of 61.59% for the PSf/4 wt% TiO2-HAP nanocomposite membrane. | [124] 2021 |

| PMR Configuration | Support | Photocatalyst | Pollutant | Main Results | Ref. Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPC + DCMD | membrane module 9 polypropylene capillary membranes | TiO2-P25 | Acid Red18 (AR18) Acid Yellow 36 (AY36) Direct Green 99 (DG99) | The presence of TiO2 and dye did not affect the permeate flux, regardless of TiO2 and dye concentrations. The MD step was very effective in rejecting the photocatalyst particles and the dye and other non-volatile compounds: so, the turbidity of distillate was similar to that of ultrapure water, regardless of the TiO2 concentrations. The high energetic consumption of MD must be considered. | [58] 2007 |

| HPC + dialysis | hollow fibers module (polyacrylonitrile or polysulfone) plate and frame module (cellophane) | TiO2-P25 | 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,4-DHBA) | Advantage 1: operation at ambient temperature. Advantage 2: no transmembrane pressure TMP → no membrane fouling. The membrane allows to maintain the TiO2 photocatalyst in the photocatalytic compartment and allows to extract the organic compounds from the turbid water. Despite these potentialities, this system was not considered elsewhere. | [60] 2007 |

| HPC + PV | GFT Sulzer Chemtech MEM 1070 | TiO2-P25 | 4-chlorophenol (4-CP) | PV positively influences HPC, and concurrently the PV takes advantage from the HPC. Drawback 1: around 50% 4-CP degradation. Drawback 2: the photodegradation intermediates are removed from the reacting environment to the permeate at a high PV rate, resulting in insufficient mineralization because of the limited residence time into the photoreactor. Drawback 3: the permeate solution, containing these by-products, need to be opportunely treated. | [134] 2007 |

| HPC + DCMD | membrane module 9 polypropylene capillary membranes | TiO2-P25 | diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen sodium salts | The efficiency of drugs removal depends on the feed matrix: ultrapure water > tap water > secondary effluent > primary effluent. No drugs were detected in distillate, 99% DOC removal for both PE and SE, and no permeate flux decline for TW and SE. During PE treatment a significant flux decline (50–60%) was observed. Then, the PE should be pre-treated before the PMR. The high energetic consumption of MD must be considered. | [132] 2014 |

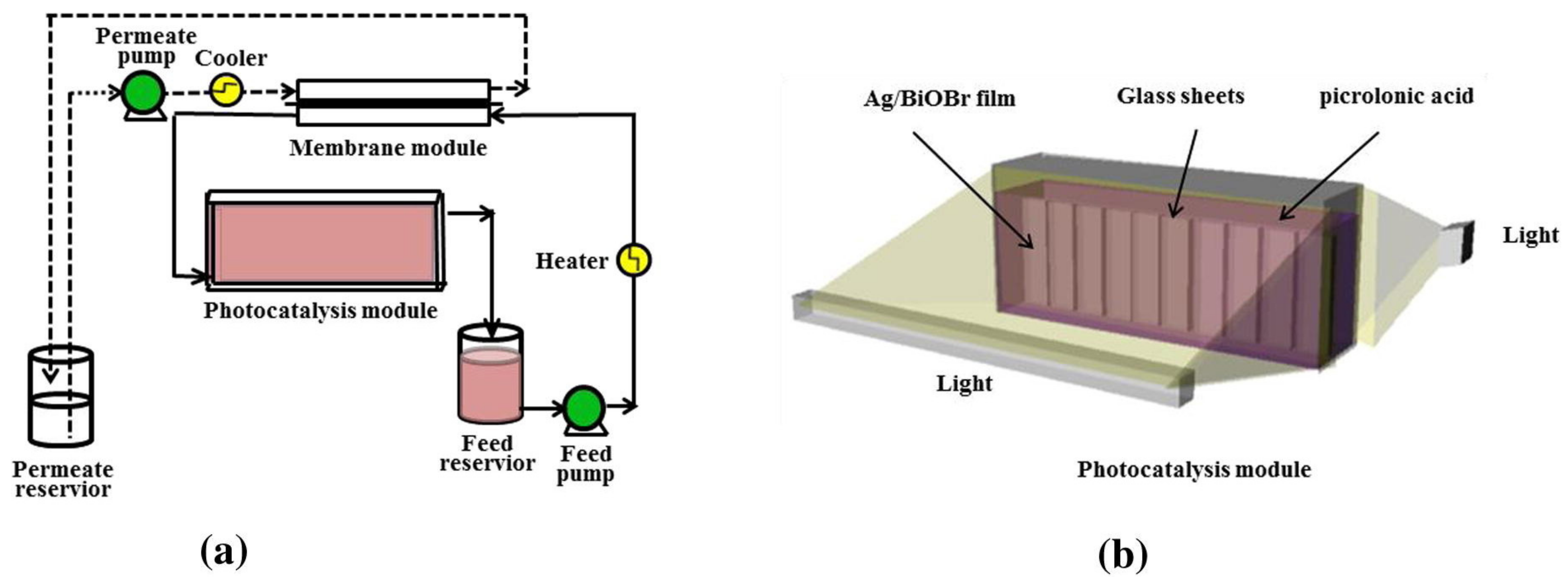

| HPC + DCMD | polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane | Ag/BiOBr | picrolonic acid | Ag/BiOBr photocatalyst mineralized PC into CO2 and inorganic nitrogen species under visible light irradiation. Simultaneously MD permitted us to produce high-quality water as the distillate. The PTFE membrane stopped the passage of picrolonic acid and nitrogen species into the distillate. The high energetic consumption of MD must be considered. | [133] 2017 |

| PMR Configuration | Support | Photocatalyst | Pollutant | Main Results | Ref. Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPC + MD | microporous hydrophobic flat sheet PTFE membrane | flower-like BiOBr microspheres | Methyl Orange | High efficiency for MO photodegradation. High quality permeate with constant flux. No membrane fouling. The high energetic consumption of MD limited its coupling with HPC for water and wastewater treatment. | [150] 2013 |

| Photocatalyst coated on the membrane | ceramic UF membranes | N-TiO2 GO-TiO2 organic shell layered TiO2 | Methylene Blue (MB) and Methyl orange (MO) | 29% and 15% MB and MO degradations by using the membrane coated with N-TiO2 under visible light irradiation. | [142] 2015 |

| Photocatalyst coated on the membrane | commercial α-Al2O3 photocatalytic membrane | N-TiO2 | Carbamazepine | Degradation rates of “flow through” the membrane > degradation rates “flow tangential to” the surface of the membrane. Enhanced photoactivity of N-doped TiO2-coated membranes under UV wavelengths, and activity under visible light. A disadvantage of coated PMRs: the photocatalytic degradation is controlled by pollutant diffusion to the catalytic surface. The increase of the mass transfer with increasing water flux was limited by membrane properties. | [143] 2016 |

| Photocatalyst deposited on the membrane | α-Al2O3 membranes | TiO2 | MB | Complete MB degradation in only 40 min under solar light irradiation. | [155] 2017 |

| Photocatalyst coated on the membrane | PVDF membrane | ZnIn2S4 | Tetracycline | Removal efficiency > 92% was maintained for 36 h of continuous operation (under influent and effluent flux of 26.09 L m−2 h−1) with 100 μg L−1 drug concentration. Good membrane stability: the surface and structure of PVDF membrane were not affected by the photocatalytic process. | [144] 2018 |

| Photocatalyst immobilized in the membrane | polysulfone membrane | novel mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride/titanium dioxide (mpg-C3N4/TiO2) nanocomposite | Sulfamethoxazole | Sulfamethoxazole was degraded into 7 non-toxic and pharmaceutically inactive by-products by the PMR technology. Satisfactory sulfamethoxazole SMX removal efficiency was obtained by operating with the membrane named PSf-3 (with 1% mpg-C3N4/TiO2 loading) for 30 h of consecutive irradiation. Good membrane stability: membrane provided a stable support with high integrity and flexibility after solar irradiation. The prepared photocatalytic membrane has a great potential to be applied in water treatment industry. | [147] 2018 |

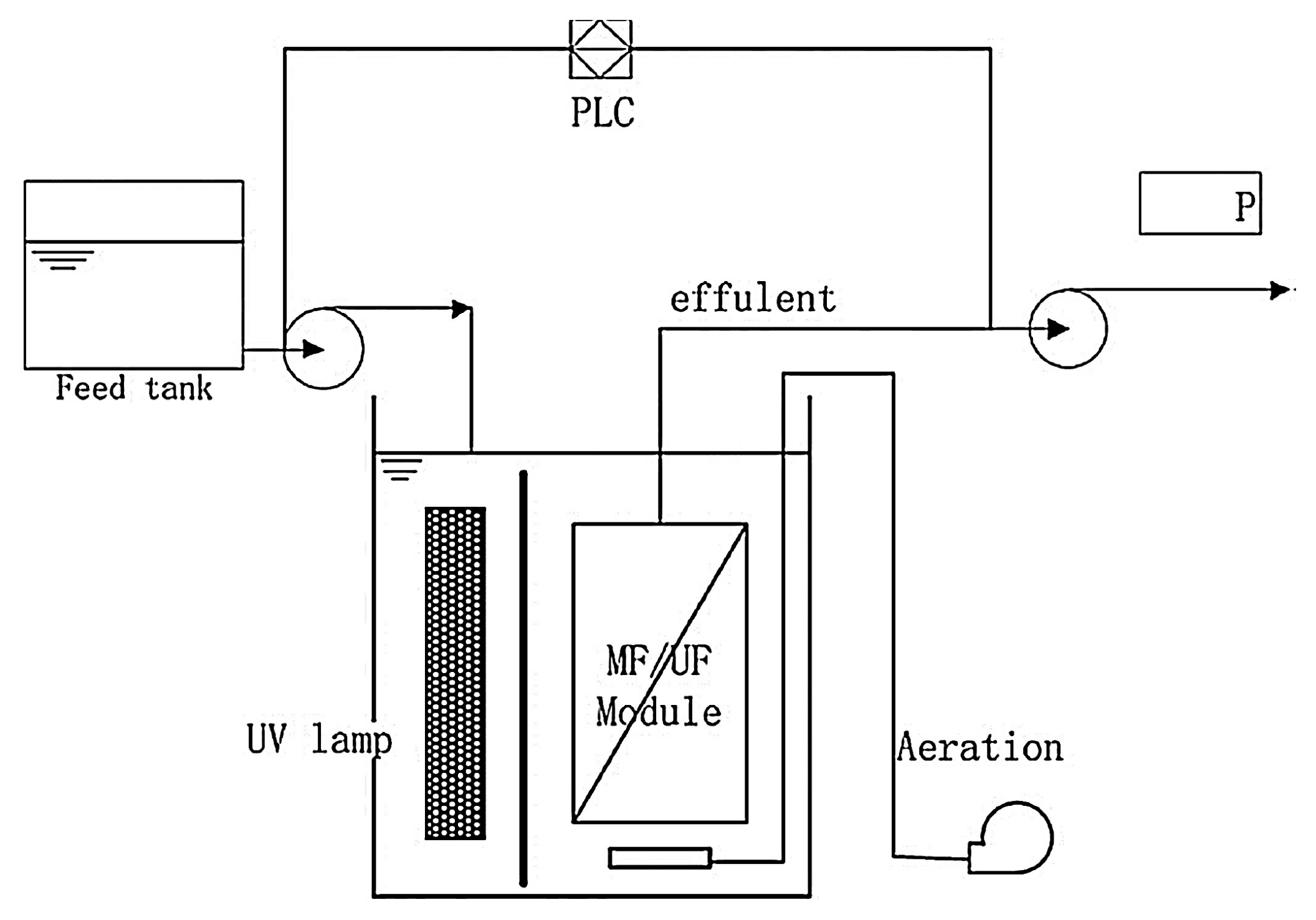

| SMPR with suspended photocatalyst | polypropylene hollow fiber membrane | Ce-ZnO nanoparticles | Reactive Orange 29 | In the best conditions, 97.84% of dye removal was achieved in the continuous flow visible light SPMS reactor. GC-Mass, COD and TOC analyses demonstrated the degradation and mineralization of RO29. The Ce-ZnO nanocomposite showed a favorable antibacterial behavior against positive and negative bacteria. | [149] 2019 |

| SMPR with suspended photocatalyst | MF ceramic membrane | N-TiO2 | Diclofenac | The efficiency of the photocatalytic process decreased by increasing the initial concentration of the drug while it was improved by adding H2O2. | [148] 2020 |

| PVDF/LDH@g-C3N4@PDA/GO composite membrane | PVDF | C3N4 | Methylene blue (MB), rhodamine b (RhB), gasoline, diesel, and petroleum | Rejection rates of methylene blue (MB), rhodamine B (RhB), gasoline, diesel, and petroleum ether were 100%, 94.61%, 96.74%, 93.22%, and 92.35%, respectively | [154] 2021 |

| PMR or Membrane Type | Photocatalyst | Application | Main Results | Ref. Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical-fiber reactor under sunlight | TiO2–SiO2 | CO2 reduction | Methane production rates of 0.177 mmol gcat−1 h−1 | [180] 2008 |

| Optical-fiber reactor under sun light | Cu–Fe/TiO2–SiO2 | CO2 reduction | Methane production rates 0.279 mmol gcat−1 h−1 | [180] 2008 |

| Polypropylene | TiO2 | Benzene oxidation to phenol | Extraction percentage of around 24% | [159] 2009 |

| Nonporous PEBAX 2533 by coupling HPC and PV | TiO2 | Photocatalytic oxidation of trans-ferulic acid to vanillin | High permeability toward VA (transmembrane flux about 3.31 gVA h−1 m2) | [163] 2012 |

| PEBAX membrane pervaporation | TiO2 | Synthesis of vanillin | Enrichment factor of VA improved | [164] 2014 |

| Polypropylene | TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 | Hydrogenation of acetophenone | Q% equal to 21.91%, productivity 4.44 mg g−1 h−1 vs. 2.96 mg g−1 h−1 of PMR vs. batch reactor | [160] 2015 |

| GQDs–Cu2O/BPM with catalyst inside the interlayer | GQDs–Cu2O | Water splitting | Membrane impedances and pH gradient formation decreased | [169] 2016 |

| Optofluidic microreactor with TiO2/carbon paper composite membrane | TiO2 | CO2 photoreduction | Methanol production yield of 111 μmol gcat−1. | [173] (2016) |

| Photocatalyst within zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF 8) | TiO2 and Cu-TiO2 | CO2 photoconversion | Methanol yield by 70% and CO yield by 233% | [174] (2017) |

| Polypropylene | Pd/TiO2/FAU | Hydrogenation of acetophenone | Productivity 99.6 mg gTiO2 −1 h−1 vs. 22 mg gTiO2−1 h−1 of PMR vs. batch reactor under visible light, Q% around 25% | [21] 2017 |

| Optofluidic planar microreactor irradiated by a 100 W LED (365 nm) | TiO2 film | CO2 reduction | methanol yield 454.6 mmol gcat−1 h−1 | [181] 2017 |

| Optofluidic membrane microreactor with simulated sun light | CdS/20 wt% TiO2/SBA-15 | CO2 reduction | 1022l mole gcat−1 h−1 obtained by using CdS/20 wt% TiO2/SBA-15 at 0.4 M NaOH concentration, | [182] 2017 |

| Membrane matrix | CdS/NH2-UiO-66 | CO2 reduction | improved CO2 photocatalytic reduction under visible light irradiation (521.9 mmol g−1 of CO produced) | [188] 2018 |

| Polycarbonate membrane | Zn doped TiO2 nanotubes | Hydrogen production | 6 times higher photocatalytic hydrogen production rate than pure TiO2 | [185] 2018 |

| Composite membrane supported on stainless steel mesh | C-doped Cr2O3/NaY | Cyclohexane oxidation | Selectivity to KA oil 99.73%, conversion efficiency of cyclohexane 0.93%. | [170] 2018 |

| Continuous photocatalytic reactor irradiated by UV light | Exfoliated C3N4-TiO2 photo-catalyst embedded in a dense Nafion matrix. | CO2 reduction | MeOH production 45 μmol gcatalyst−1 h−1. | [175] 2019 |

| Water splitting and biofouling reduction | S-doped g-C3N4 | Water splitting | H2 and O2 evolution rates in the system were 24.6 and 14.5 µmol−1 h−1. Biofouling reduction. | [161] 2020 |

| Photocatalytic membrane reactor (dialysis) | TiO2 | Photocatalytic oxidation of trans-ferulic acid to vanillin | The total amount of vanillin produced after 5 h in the membrane reactor was more than one-third higher than in the photocatalytic reactor without dialysis. | [59] 2020 |

| GAZO composite | ZnAl2O4 | Hydrogen generation | Hydrogen generation rates of 4640 and 2860 μmol g−1 h−1 were obtained for ZAO powder and GAZO composite, respectively. | [171] 2020 |

| Two-layer photocatalytic membranes: polyethersulfone-TiO2 (PES-TiO2) and poly-ether-block-amide (PEBAX-1657) | TiO2 | Conversion of CO2 | Methanol production yield about 697 μmol gcat−1 h−1 in the presence of water at 5 wt% of TiO2 nanoparticle contents, 3 mL min−1 of water flow rate and 8.84 W cm−2 of light power. | [172] 2021 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. The Evolution of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors over the Last 20 Years: A State of the Art Perspective. Catalysts 2021, 11, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11070775

Molinari R, Lavorato C, Argurio P. The Evolution of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors over the Last 20 Years: A State of the Art Perspective. Catalysts. 2021; 11(7):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11070775

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolinari, Raffaele, Cristina Lavorato, and Pietro Argurio. 2021. "The Evolution of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors over the Last 20 Years: A State of the Art Perspective" Catalysts 11, no. 7: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11070775

APA StyleMolinari, R., Lavorato, C., & Argurio, P. (2021). The Evolution of Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors over the Last 20 Years: A State of the Art Perspective. Catalysts, 11(7), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11070775