Abstract

Catalytic oxidation is a key technology for the conversion of petroleum-based feedstocks into useful chemicals (e.g., adipic acid, caprolactam, glycols, acrylates, and vinyl acetate) since this chemical transformation is always involved in synthesis processes. Millions of tons of these compounds are annually produced worldwide and find applications in all areas of chemical industries, ranging from pharmaceutical to large-scale commodities. The traditional industrial methods to produce large amounts of those compounds involve over-stoichiometric quantities of toxic inorganic reactants and homogeneous catalysts that operate at high temperature, originating large amounts of effluents, often leading to expensive downstream processes, along with nonrecovery of valuable catalysts that are loss within the reactant effluent. Due to the increasingly stringent environmental legislation nowadays, there is considerable pressure to replace these antiquate technologies, focusing on heterogeneous catalysts that can operate under mild reactions conditions, easily recovered, and reused. Parallelly, recent advances in the synthesis and characterization of metal complexes and metal clusters on support surfaces have brought new insights to catalysis and highlight ways to systematic catalysts design. This review aims to provide a comprehensive bibliographic examination over the last 10 years on the development of heterogeneous catalysts, i.e., organometallic complexes or metal clusters immobilized in distinct inorganic supports such as zeolites, hierarchical zeolites, silicas, and clays. The methodologies used to prepare and/or modify the supports are critically reviewed, as well as the methods used for the immobilization of the active species. The applications of the heterogenized catalysts are presented, and some case-studies are discussed in detail.

1. Industrial Hydrocarbon Oxidation Reactions

Catalytic oxidation reactions are of high industrial relevance since many important commodities have synthesis paths involving oxidation. To understand their relevance, we can just refer to adipic acid, with a global production of over 4 million tons and expect to exceed a $8 billion USD global market by 2025 [1].

If like some authors [2] we include ammoxidation (a process using ammonia and oxygen) and oxychlorination (a process using hydrogen chloride and oxygen) used, respectively, in the production of acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride monomers, the industrial importance of oxidation reactions is even higher.

Despite the focus of this manuscript being on hydrocarbon oxidation reactions, it is also worth mentioning the industrial importance of alcohols oxidation, namely methanol and ethanol to produce, correspondingly, formaldehyde (e.g., Formox process) and 1,3-butadiene [3].

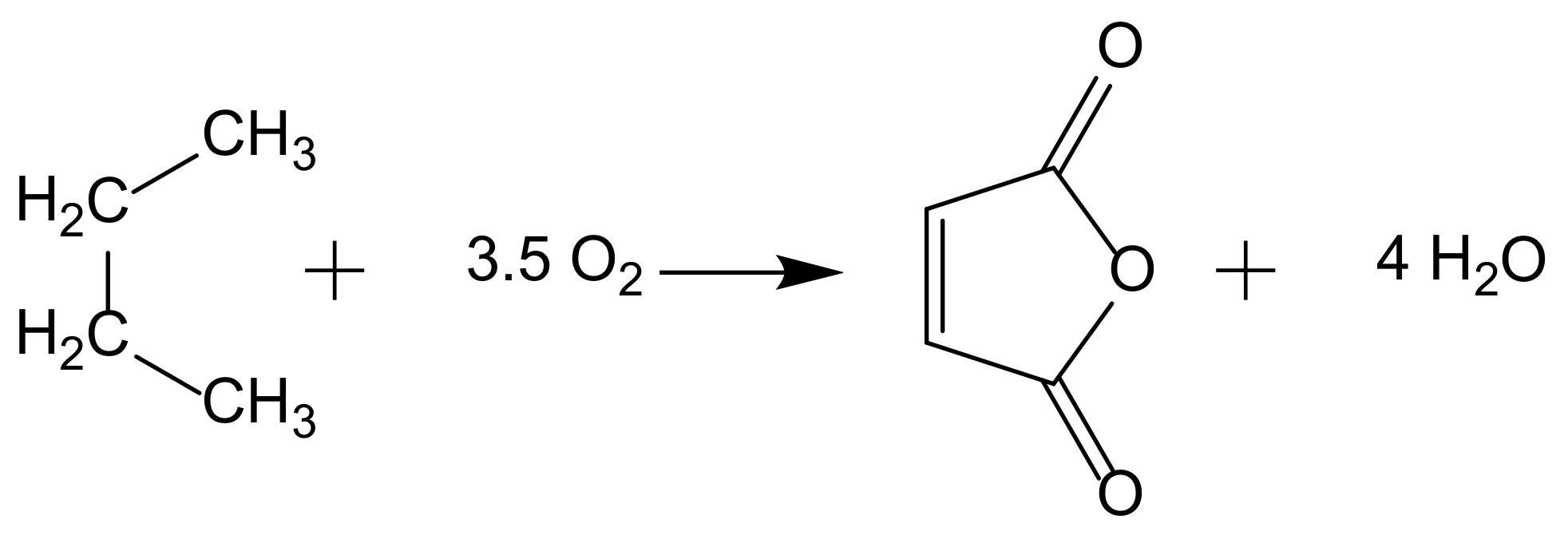

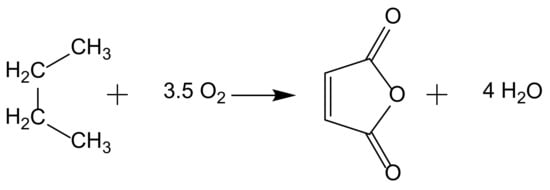

When addressing hydrocarbon oxidation reactions, there are several significant industrial applications. The direct oxidation of alkanes is an attractive alternative to oxidation via olefins; however, only two industrial processes have been implemented, and other alkanes oxidations are only at the research or pilot plant status. One of these reactions is the production of maleic anhydride from n-butane (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Maleic anhydride synthesis from n-butane oxidation.

This process uses supported (VO)2P2O7 as heterogenous catalyst and achieves high weight yields (ca. 95%) replacing a previous method with benzene. In both methods, butane (or benzene) is fed into a stream of hot air, and the mixture passes through a catalyst bed at high temperature. Fixed, fluidized, and transport bed reactors technologies have been implemented in different industrial plants to address different technical difficulties [4].

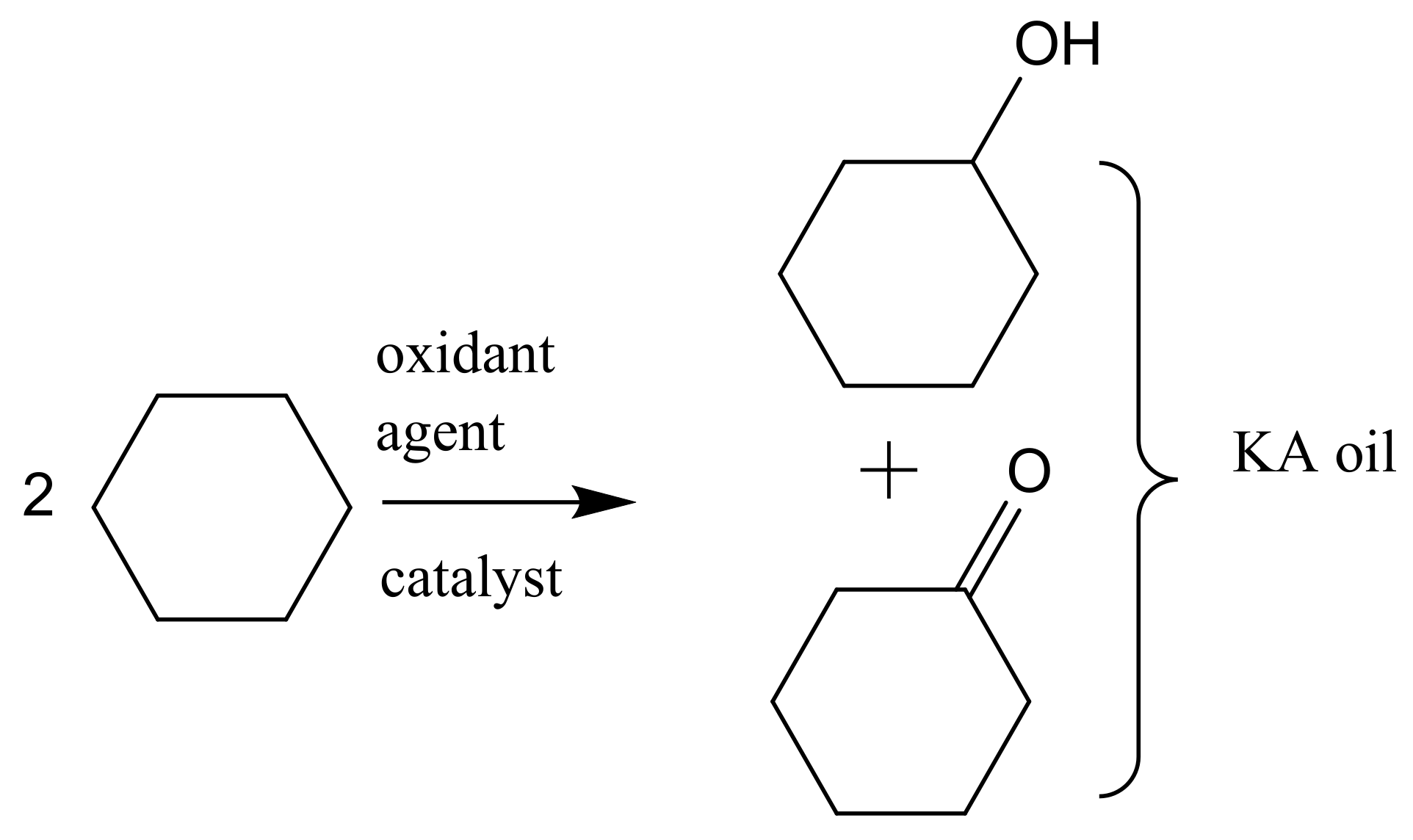

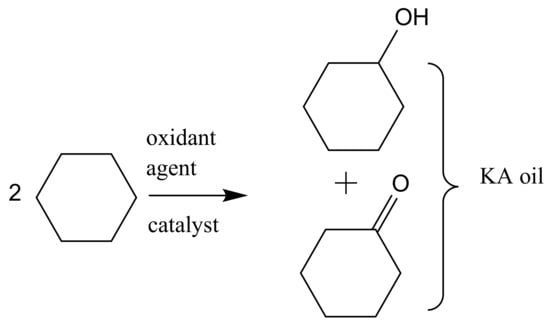

Another example of alkane oxidation but in the liquid phase with homogeneous catalysis is the oxidation of cyclohexane into a mixture of cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone (also known as KA oil), which are intermediates in the manufacture of nylon-6 and nylon-6,6. KA oil is mainly obtained through the oxidation of cyclohexane using air or peroxide as the oxidant agent. In the present industrial conditions, liquid phase oxidation of cyclohexane is achieved at about 165 °C and O2 pressures of 8–15 bar in the presence of manganese or cobalt naphthenates as catalysts (Figure 2). To avoid oxidative side reactions, a short retention time is used to assure 80–85% selectivity; thus, the conversion is limited to 10–11% per cycle, requiring separation and refeeding of the unconverted cyclohexane. Additionally, the currently used homogeneous catalysts are difficult to separate from the reaction media, leading to serious environmental pollution. [5]

Figure 2.

Oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone (KA oil).

There are several industrial alkenes oxidation processes, and two of the major products obtained by these methods are ethylene oxide and acetaldehyde. Both chemicals are produced from ethylene and are in turn raw materials to produce other compounds such as ethylene glycol, diethylene glycol, triethylene glycol (from ethylene oxide) and acetic acid, acetate esters, and pyridine derivatives (from acetaldehyde).

The current ethylene oxide production process was developed in the middle of the 20th century and uses finely dispersed metallic silver together with alkali and alkaline earth metals promoters, on ultrapure aluminum oxide, i.e., a low surface area support. There are two variations of this process: one uses air and the other oxygen, and both use fixed bed reactors which consist of large bundles of thousand tubes, each with a length of approximately 10 m and an internal diameter of 20–50 mm. The temperature and the pressure range between 200 and 300 °C and 15 and 25 bar, respectively.

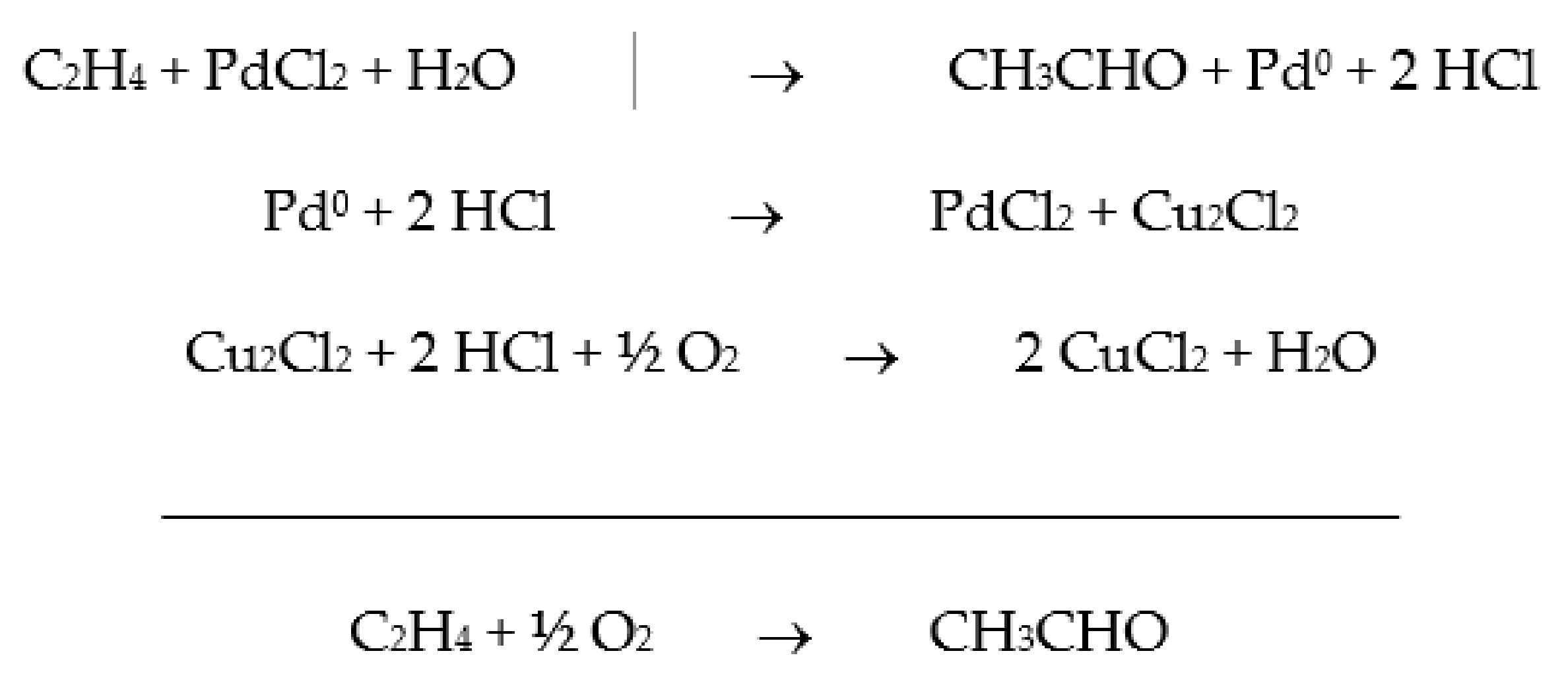

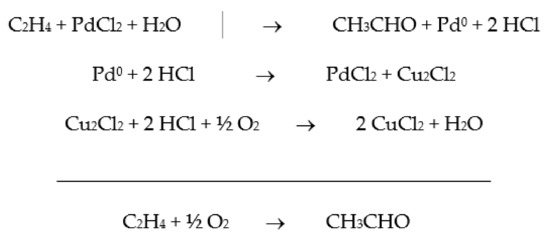

The oxidation of ethylene to acetaldehyde, known as the Wacker process, was one of the first industrial homogeneous catalytic process (Scheme 1). The catalyst is a two-component aqueous solution consisting of PdCl2 and CuCl2, and from the proposed mechanism, O2 is not directly involved.

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism for the ethylene oxidation to acetaldehyde.

The process is a two-phase gas/liquid system, and there are variations in different industrial units, with some using a single-step process and others a two-step process. Each solution has different operational conditions and advantages.

As the final examples of substrates used in industrial hydrocarbon oxidation reactions, we can include the oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons. Even though benzene oxidation is still not near industrial application, due to increasing ring activation with oxidation and further reactions, other molecules are already used.

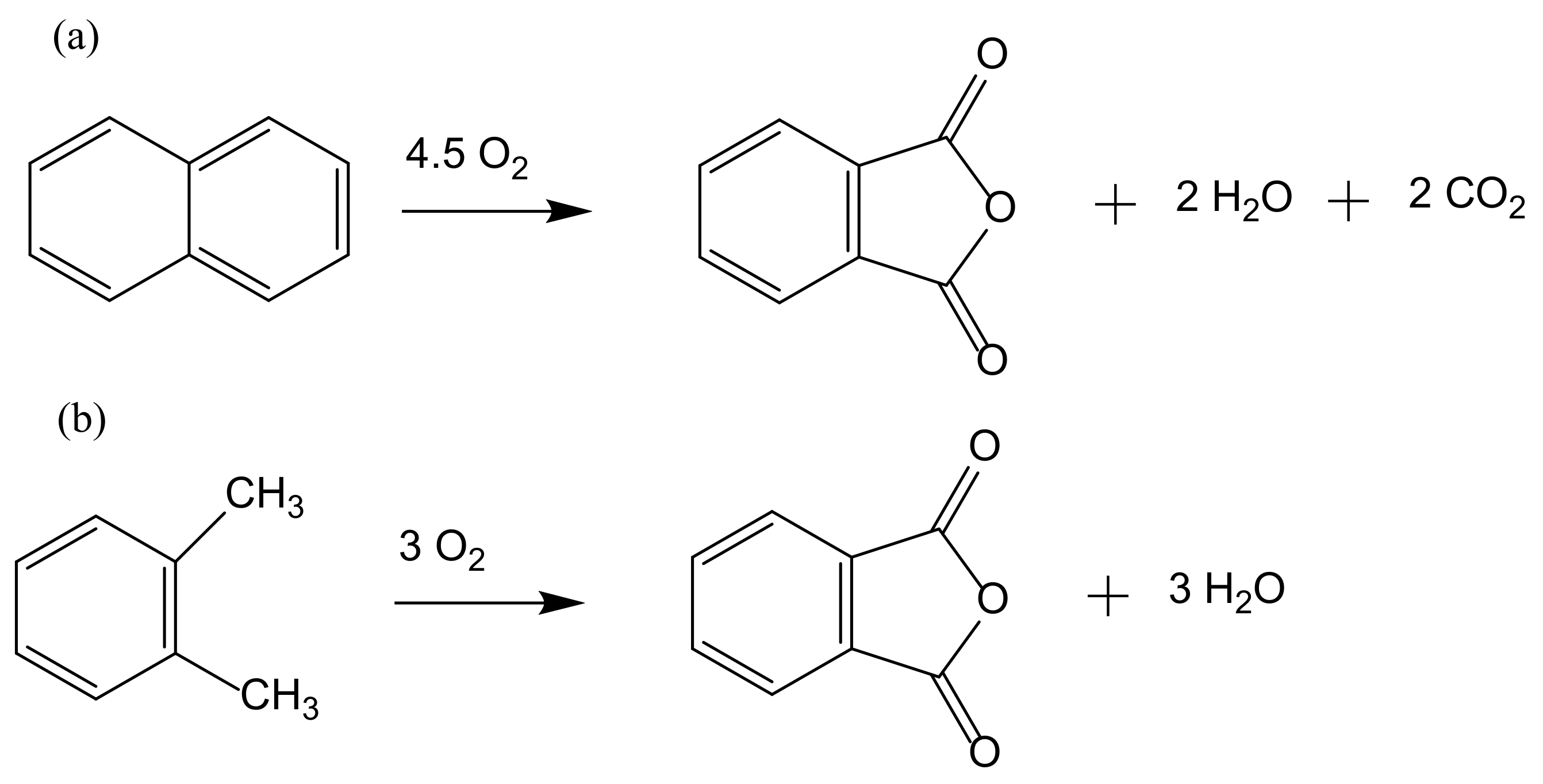

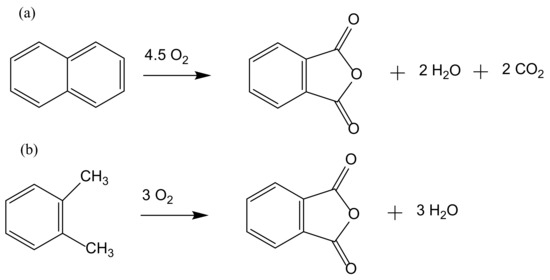

The production of phthalic anhydride, a precursor of phthalate esters plasticizers, dyestuffs, and pharmaceuticals, is based on the oxidation reaction of naphthalene. Initially, the process was liquid phase based but was subsequently replaced by a cleaner gas phase process using mercury salt as a catalyst. A variation of this process uses o-xylene instead of naphthalene with further variations in the used catalysts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Oxidation of naphthalene (a) and o-xylene (b) to phthalic anhydride.

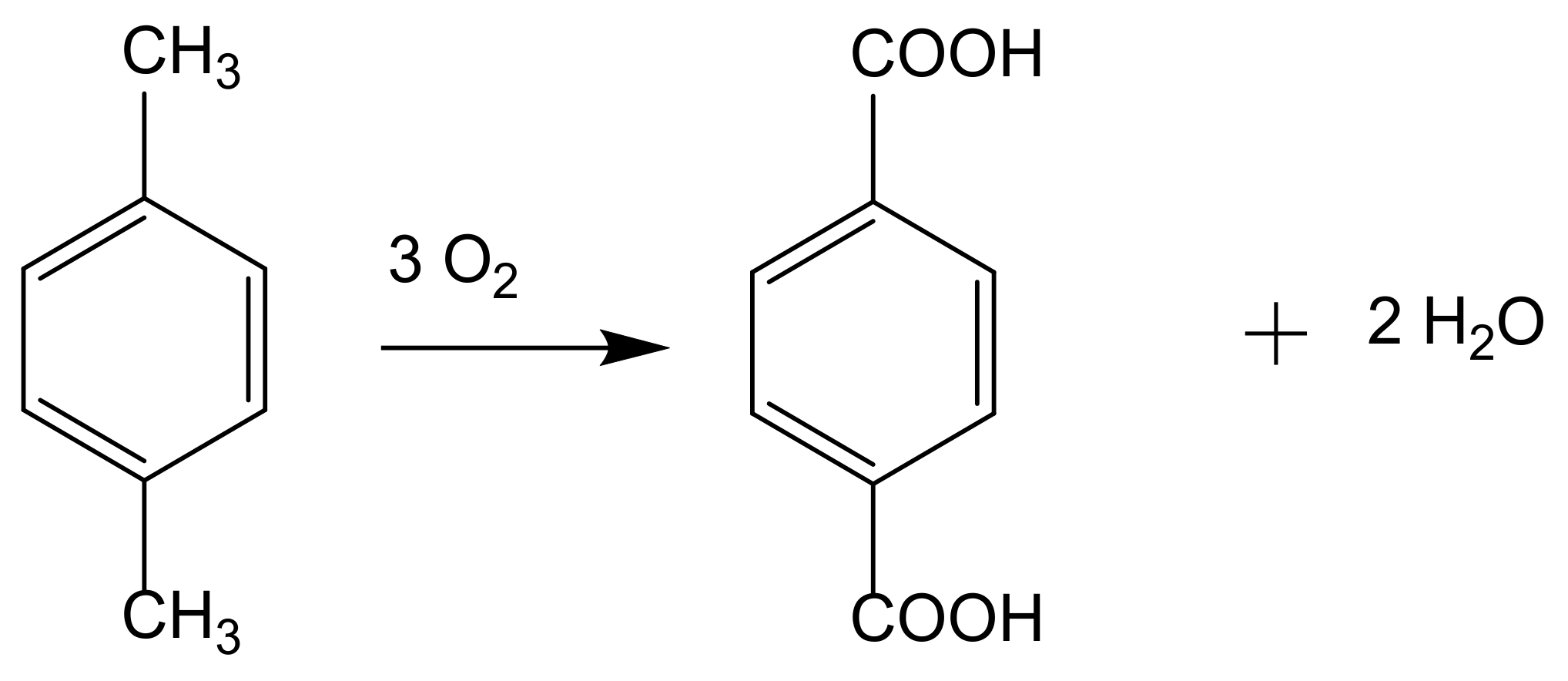

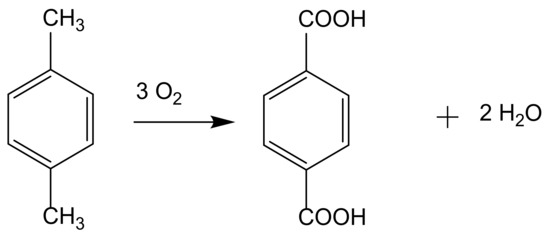

A xylene isomer is also used in one of the most important industrial oxidation reactions, the production of terephthalic acid from p-xylene (Figure 4). The relevance of terephthalic acid is based on being the precursor to polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the highest volume synthetic fiber. Since the 1960s, terephthalic acid has been mainly produced by the Amoco process; this homogeneous catalytic process uses soluble cobalt salt (acetate or naphthenate) simultaneously with manganese or bromide ions [3,4].

Figure 4.

Terephthalic acid production from p-xylene oxidation.

2. From Homogeneous to Heterogenized Catalysts

The development of sustainable methods for the catalytic oxidation reactions of hydrocarbons-alkanes, alkenes, and aromatics is an important scientific challenge with significant technological potential. As mentioned previously, these reactions usually occur in the presence of traditional homogeneous catalysts, such as transition and neat metals or their salts, as well as mineral acids and complexes, due to their high activity and selectivity to the desired products. However, the intensive use of these catalysts is rather controversial due to the difficult separation and recovery of the catalyst from the reaction media. The immobilization of catalytic active species in solid supports is a possible strategy to overcome some of the disadvantages of homogeneous processes. Heterogenized catalysts are easily recovered from the reaction media, without expensive separation processes and large amounts of solvents involved, with the additional advantage of allowing the reuse of the catalyst in several cycles. These are, in fact, the main objectives that one expects to achieve through the immobilization of homogeneous catalysts, but some additional benefits may also be obtained, namely when porous supports are considered. In this case, the confinement effects may enhance the interaction of the substrate with the catalyst. However, the porosity of the support may also impose some diffusional constrains that, especially when voluminous subtracts are considered, can result in an extensive loss of activity. In the case of complexes, the immobilization on solid supports has another additional benefit since it prevents dimerization phenomena that are some of the most common causes of homogeneous catalysts deactivation.

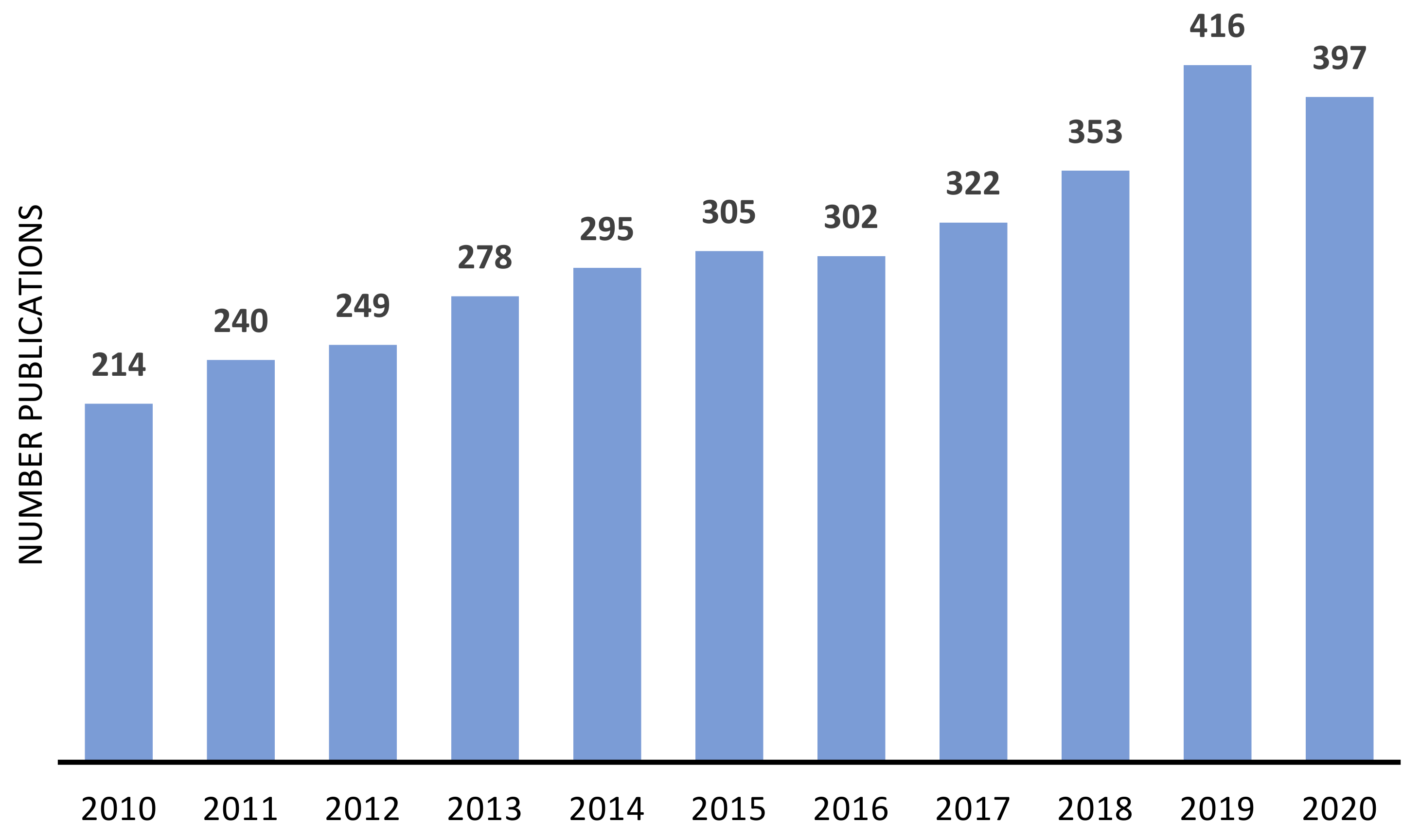

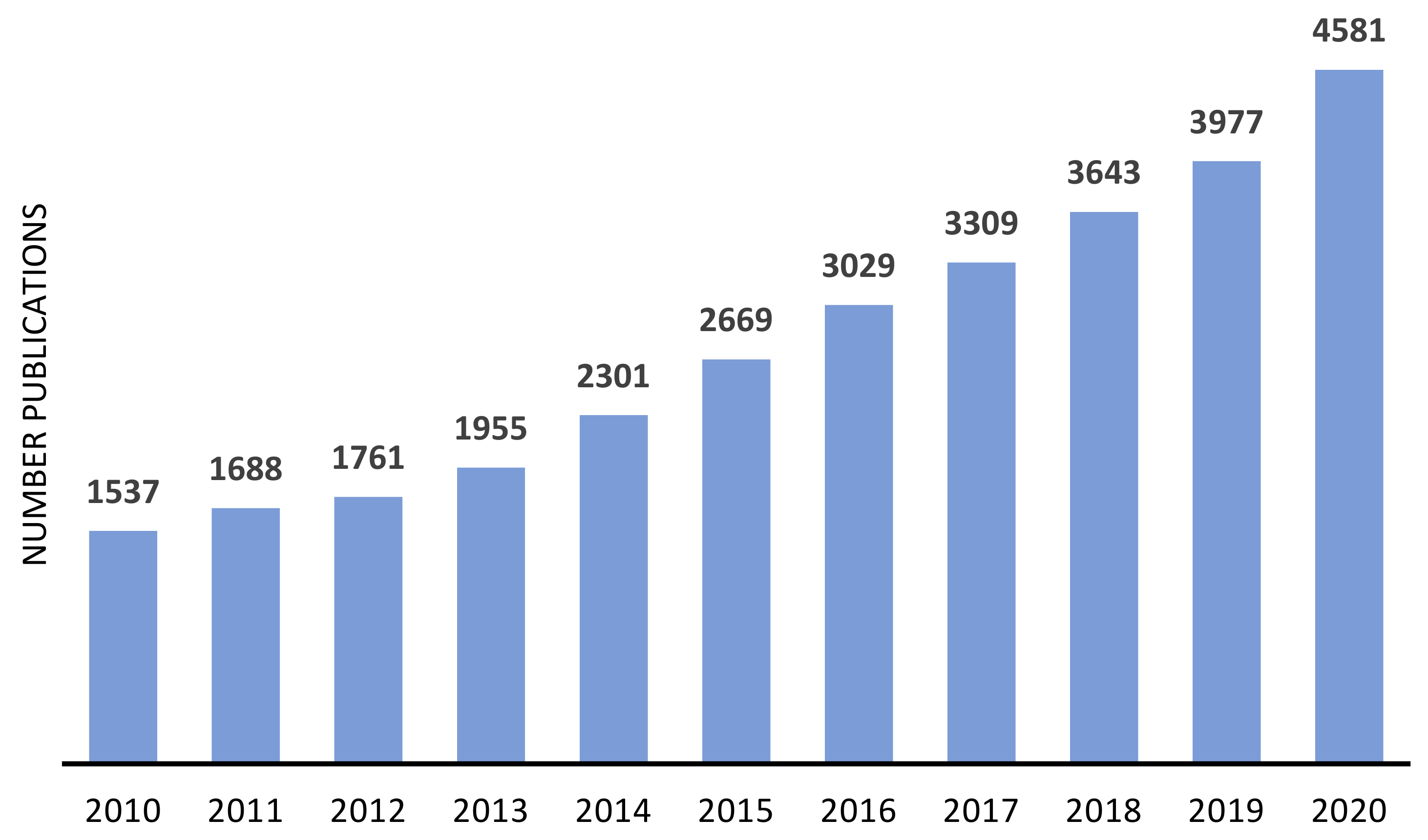

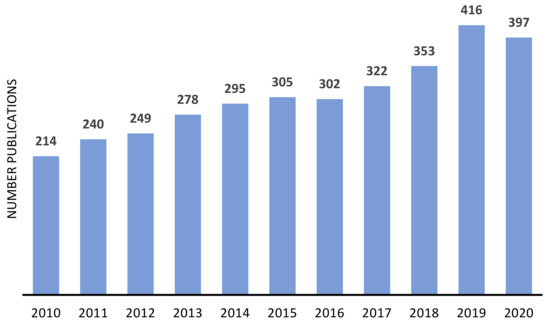

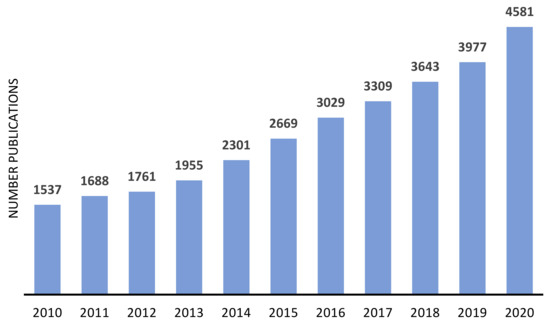

The advantages of immobilized catalyst have been attracting the attention of both industrial and academic researchers, as demonstrated by the number of publications focused on the heterogenization of metal or metal complexes, on zeolites and similar materials, in the last decade (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In both cases, the number of publications presents a continuous growing, being more consistent in the case of metal-supported catalysts.

Figure 5.

Approximate annual number of publications on immobilized metal complexes on zeolites and other similar materials since 2010. Source: ISI Web of Knowledge, 29 September 2021. Search terms: “immobilized metal complexes” OR “anchored metal complexes” OR “heterogenized metal complexes”.

Figure 6.

Approximate annual number of publications on metal supported on zeolites and other similar materials, since 2010. Source: ISI Web of Knowledge, 29 September 2021. Search terms: “metal-supported catalysts”.

3. Zeolites and Related Materials as Support for the Heterogenization of the Catalysts

Zeolites are microporous, crystalline aluminosilicate materials known since 1756 when the stilbite structure was identified by the Swedish mineralogist Crönstedt. This class of materials is composed of corner-sharing TO4 tetrahedra, where T represents Si or Al. Adjacent SiO4 and AlO4−tethraedra are bridged by oxygen atoms that are arranged in a regular way, giving a three-dimensional system of cages and pores with dimensions comprised in the microporous range, i.e., between 3 and 20 Å, which is responsible by the “molecular sieving” property [6].

Zeolites were firstly considered as mineralogical curiosities and only became industrial important after the studies performed by Barrier and Milton in the 1940s [7,8], reporting the successful synthesis of numerous zeolite structures. Since then, zeolites have been widely used mainly as adsorbents, ion exchangers, and, especially, as heterogeneous catalysts or as catalyst supports. Nowadays, according to the International Zeolite Association (IZA), which catalogues all zeolite structures, which can be consulted at Reference [9], there are more than 240 synthetic zeolites and 67 natural zeolites.

To maintain the electroneutrality of the zeolite framework, the presence of a compensation cation, such as Na+, is required, giving the ability to act as ion-exchange materials with a large application in detergents industry as water-softening agents. When the compensation cation is H+, the zeolite has a high content of Brönsted acid sites, allowing one to catalyze many reactions involving hydrocarbons. Allying a strong acidity with other unique properties, such as structural, thermal, mechanical, and chemical stability, makes zeolites ideal heterogeneous catalysts for gas-phase reactions that are typically conducted at temperatures higher than 300 °C. In fact, most of the current large-scale commercial processes in the petroleum refining and petrochemical industries use zeolite-based catalysts [10]. These processes involve cracking, isomerization, and transalkylation reactions. After several catalytic cycles, the catalysts may become deactivated due to the adsorption of products, byproducts, or the formation of coke, but in many cases, zeolites can easily be reactivated by performing thermal treatments. In addition, when they are exhausted and at the end of their regeneration cycles, they can be used as precursors for producing concrete [11], new adsorbent materials for the withdrawing of pollutants from the environment [12], or even new catalysts [13].

The catalysts can be classified according to the nature of their active sites as intrinsic, when the active sites are naturally present in the composition of the catalyst, for example Brönsted or Lewis acid sites in zeolites, or supported catalysts when the active sites are introduced on a solid support that has no catalytic activity on the targeted reaction [8]. As mentioned before, the immobilization of a catalysts/catalyst precursor is a common procedure, combining the advantages of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts. The mechanical stability and high porosity of zeolite structures makes them very interesting supports with great advantages for certain immobilization methodologies and for recycling and reuse procedures. Most of the studies report the immobilization of metal complexes [14,15,16,17,18] and metal particles [19,20,21], which are the topics of the present review, but the immobilization of other species (out of the scope of this review) such as enzymes [22,23] has also been presented.

3.1. Hierarchical Zeolites

The strictly microporous nature of zeolite structures is responsible for the various types of shape selectivity that are fundamental to increasing the yield of a desired product. A classic example of shape selectivity is an important petrochemical reaction catalyzed by ZSM-5 zeolite (MFI structure): the transformation of m-xylene into o-xylene and, especially, p-xylene, which is the building block to produce polyethylene (PET)-based products. In this case, opposing the thermodynamic equilibrium where the more stable m-xylene is favored, the diffusional limitations for the molecular transport of m-xylene and o-xylene lead to the conversion of these two more voluminous isomers into the most valuable p-xylene [8,24]. Despite the importance of shape selectivity in several reactions catalyzed by zeolites, their native microporosity can also impose diffusion constraints that will limit the catalytic performance, especially in the presence of bulky molecules. Within the past two decades, intense attention has been devoted to the enhancement of accessibility of active sites in microporous zeolite frameworks. Although a large number of strategies have been proposed and demonstrated, the production of these hierarchical materials can be classified into two major categories: synthesis procedures, also called “bottom-up”, or postsynthesis procedures, also called “top-down”[25].

3.1.1. Bottom-Up Strategies

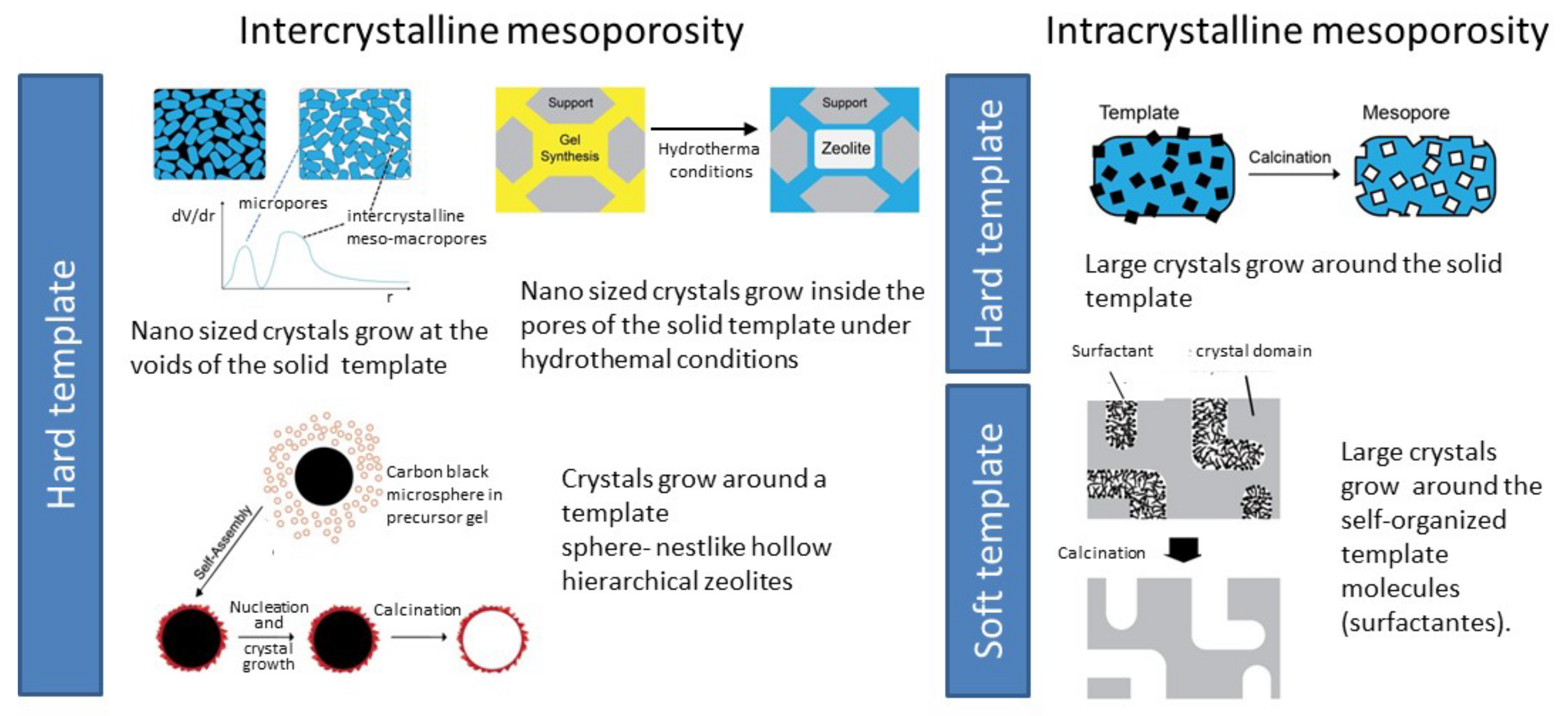

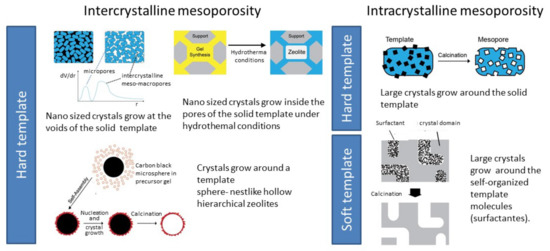

To introduce a supplementary pore system, usually mesopores, several strategies involve the addition of hard or soft templates to the synthesis gel, allowing the crystallization of the zeolites around those templates, giving intracrystalline mesoporosity. Alternatively, the crystal can grow at the confined space between particles, originating small crystals where the mesopores appear as the consequence of the particle stacking (intracrystalline mesoporosity), as schematized in Figure 7. In both cases, after synthesis, the templates are removed by combustion, exposing the mesopores.

Figure 7.

Overview of the various bottom-up synthesis methodologies to obtain hierarchical zeolites.

Table 1 resumes some representative examples regarding the application of hard and soft templating strategies for the synthesis of hierarchical zeolites. A few examples, related with the targeted reactions of this review, are briefly mentioned in the following section, and selected case-studies are discussed in detail ahead.

Table 1.

Examples of recent studies on bottom-up processes used to synthetize hierarchical zeolite structures.

Hard Templating

The first studies concerning bottom-up strategies reported the use of solid templates by Madsen and Jacobsen in 1999. The authors used carbon black particles to develop mesoporosity in MFI zeolite structure using different synthesis strategies and obtained nanosized zeolite crystals with intercrystalline mesoporosity [26] and, later, mesopore zeolite crystals with intracrystalline mesopores [27]. Following the same procedure, Koekkoek and coworkers [29] reported the use of uniform size carbon black particles (BP2000) to act as a solid template along with Fe(NO3)3.9H2O for the synthesis of hierarchical Fe/ZSM-5 and obtained materials with uniform mesopore size distribution. The hierarchical catalysts exhibit superior catalytic performance, especially in terms of stability, in the selective oxidation of benzene to phenol. Soon, the same synthesis strategies were applied to a wide range of zeolite structures, as can be seen in Table 1. However, as some carbon black had a wide range of particle size, leading to randomly oriented or cavern-like mesopores, other carbon materials soon emerged as possible templates, such as, carbon nanotubes [34] or nanofibers [31], as well as the application of other materials such as polymers [43], or even more creative biological materials, such as starch [40], wood cells [41], or even leaves and stems of plants [42]. The use of these materials as templates brings the advantage of being abundant and relatively inexpensive, as well as offering a great diversity of shapes and sizes. A different, but also sustainable, approach was recently reported Li et al. [13] that used a wasted zeolite catalysts (coke-spent MFI zeolite) to produce hierarchical SSZ-13 zeolites (CHA structure), providing an efficient procedure to transform a waste zeolite catalyst into a new and valuable hierarchical zeolite.

Soft Templating

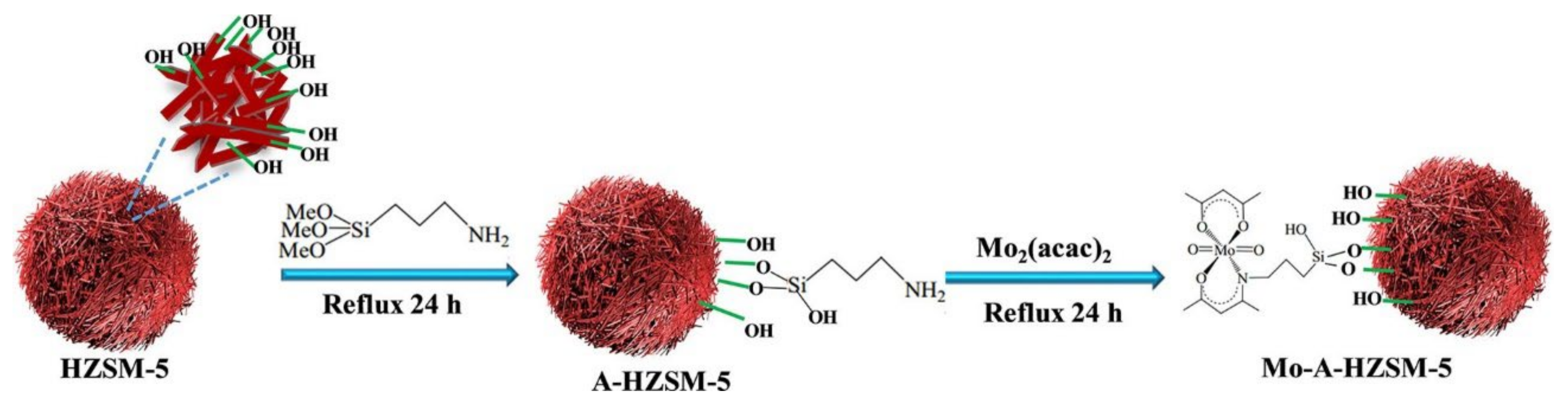

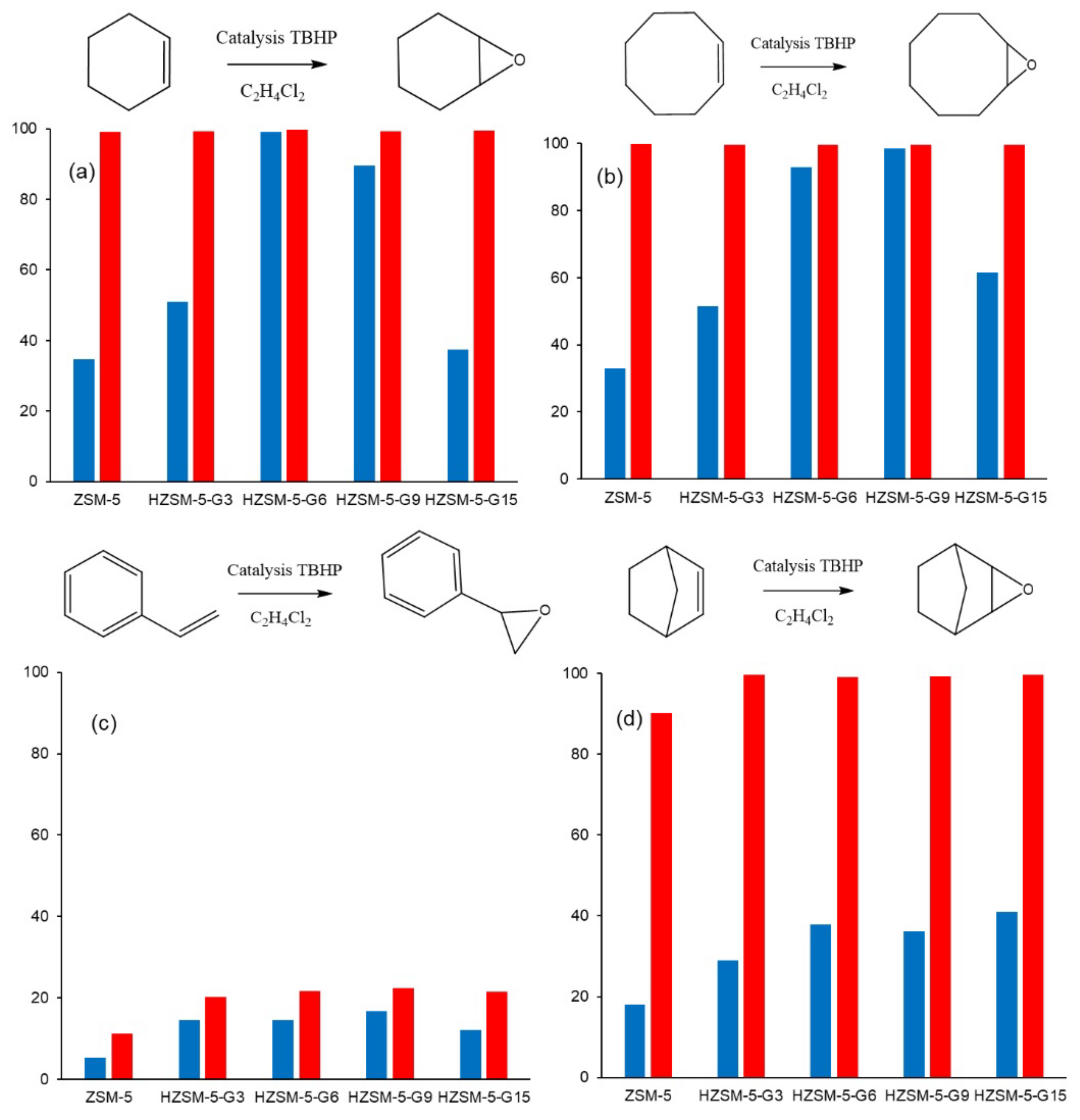

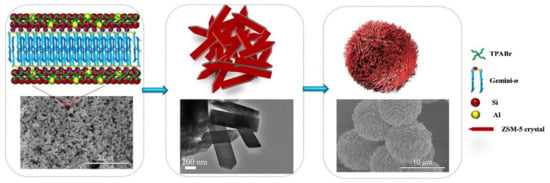

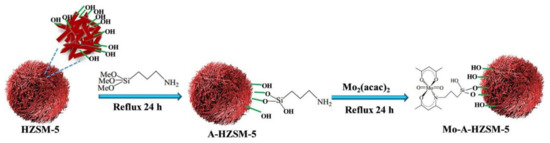

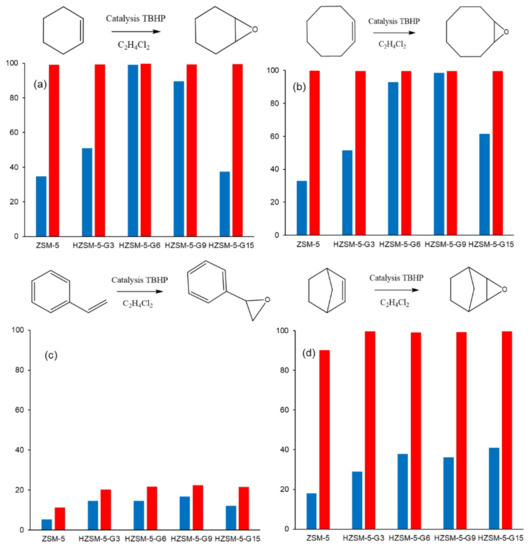

As an alternative to the use of solid materials as templates, the use of macromolecules has also been reported to produce hierarchical zeolites. The name “soft” comes from the fact that the extraporous system is generated by the presence of a macromolecule/surfactant that is added during the synthesis of the zeolite structure. Soft templating strategies can be categorized into primary or secondary methods. In the first case, all components including the soft template are introduced at the beginning of the synthesis, whereas in the second case the surfactant is added prior to the hydrothermal step [59]. The first methodology produced hierarchical zeolites with a high degree of mesoporosity. However, this strategy uses, frequently, surfactants that are not commercially available, as they prepared prior to zeolite synthesis, making this method expensive [25]. An example was recently reported by Li and coworkers [48] who prepared a series of Gemini surfactants to act as surfactants that were added directly to the synthesis gel to produce hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite (see Figure 8). The obtained materials with abundant intercrystalline mesoporosity contained a large amount of hydroxyl groups on the crystal surface that were used to immobilize a molybdenum compound and, later, used as supported catalysts for epoxidation of alkenes.

Figure 8.

Proposed formation process for the synthesis of HZSM-5 using Gemini-n as a mesoporous structure directing agent. Reproduced with permission from Reference [48]. Copyright (2021), Wiley-VCH GmbH.

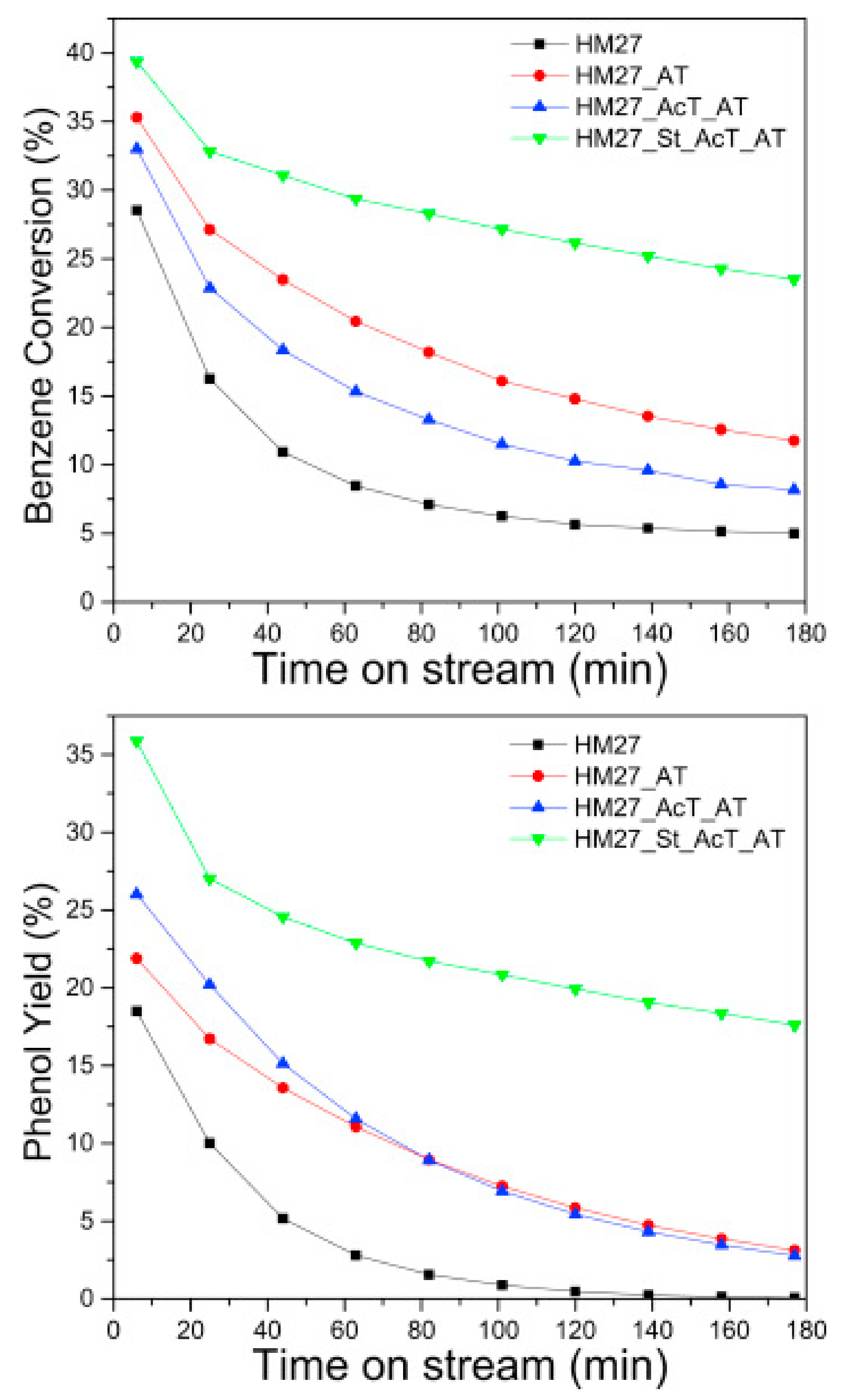

In secondary methods, a two-step synthesis procedure is carried out: on the first step, the zeolite synthesis gel is left to age in the absence of the surfactant at temperature around 100 °C for different periods of time to form seeds (subnanocrystals), and in the second step, a solution of the surfactant is added to direct the self-assembly of precrystalline zeolite units during the hydrothermal synthesis. This methodology was successfully used by Narayanan et al. [56] who added a nonionic surfactant (Triton-X, commercial designation of polyethylene glycol tert-octylphenyl ether) as mesoporogen template to the zeolite seeds, before the hydrothermal step. The textural analysis showed the presence of meso- and macro-pores without intensively destroying the microporosity, which allowed a significant higher conversion and reusability in the liquid phase oxidation of toluene. A variation of the secondary method consists of the creation of additional porosity in zeolites through the generation of biphasic emulsions. According to this methodology, a mixture containing the surfactant and an aqueous phase undergoes a phase-separations in order to obtain a stable biphasic emulsion [53,54]. A successful example of this procedure is described by Koekkoek et al. [55], where hierarchical MFI zeolite was prepared in the presence of TPOAC (dimethyloctadecylammonium chloride) surfactant in methanol (60% w/w), followed by the addition of an iron precursor solution. The Fe hierarchical ZSM-5 catalysts, made up from very small microporous zeolite domains with sizes below 50 nm integrated into highly mesoporous particles, were used in selective oxidation of benzene. As a final remark, it must be mentioned, in agreement with Schwieger et al. [25], that secondary methodologies are dual, since they can also be understood as Post-synthesis treatments, attending that the generation of the additional porosity occurs after the crystallization of the zeolite seeds.

Besides the approaches mentioned before, hierarchical zeolites can also be prepared using microwave radiation, which is a low-frequency form of electromagnetic energy that is commonly used to speed up slow reactions where high activation energies are required. The synthesis of hierarchical zeolites and zeotypes (i.e., crystalline structures based on the zeolite frameworks but with other elements than Al and Si, as is the case of SAPO, a silicoaluminium phosphate) using microwave radiation takes advantage of the reduced time needed to accomplish the crystallization step; thus, small crystals are obtained with intercrystalline porosity that results from crystal stacking. An extensive review concerning the synthesis of several zeolite structures and related materials using microwave radiation was presented by Tompsett et al. [60].

3.1.2. Top-Down Strategies

Postsynthesis or top-down strategies comprise the treatments performed on previously synthesized zeolites, aiming to modify its porosity through the creation of a secondary pore system, generally mesopores. Some strategies are low cost since they involve cheap and common reactants to modify the zeolite porosity. On the other hand, the starting materials are generally commercial and robust structures with consolidated properties in adsorption and catalysis fields. The most common strategy to develop mesoporosity in a presynthesized zeolite is the demetallation, i.e., the removal of T atoms, either aluminum (dealumination), or silicon (desilication). Unfortunately, a common drawback of these procedures is that they may lead to significant mass losses that are reflected in significant impact on zeolite crystallinity and acidity. This is particularly important in more sensitive zeolite structures; thus, a careful choice of the experimental conditions, such as temperature, acid/base concentration, and duration of the treatment, is fundamental for obtaining hierarchical porosity, not disregarding other important properties such as crystallinity and acidity.

Table 2 displays some representative examples concerning strategies to attain demetallation in zeolite structures, that is, dealumination and desilication. Some examples are briefly mentioned in the following section, and selected case studies are analyzed in more detailed in the catalytic applications section.

Table 2.

Examples of recent studies on dealumination and desilication processes used to prepare hierarchical zeolite structures.

Dealumination

Dealumination is the oldest postsynthesis treatment that was originally developed to control the number and strength of acid sites in low-silica zeolites, through the increase in their Si/Al ratio. The procedure, firstly explored by Barrer and Makki in the 1960s [76], consists of the selective removal of Al atoms from the zeolite framework, leading to the creation of vacancies that constitute the additional porosity, mainly mesopores. Further, the hydrothermal stabilization of the zeolite structure is also achieved. There are several review papers that report dealumination procedures in several zeolite structures [25,77,78,79,80], being the larger number of publications dedicated to FAU structure due to the important industrial application of dealuminated Y zeolite in the fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) process [81].

The routes for extracting aluminum from a zeolite structure can be classified into two general groups: hydrothermal treatments and treatments employing chemical agents, mostly acids. Nevertheless, hydrothermal treatments, especially steaming are, by far, the most explored methodology, which is not surprising, considering that this method is used to produce ultrastable Y zeolite (USY), which is the base catalyst for the FCC process [81]. Acid treatments are also widely explored, as the main dealumination procedure or, more commonly, as a second step treatment to enable the removal of extra framework material formed during the hydrothermal process. Independently of the dealumination method used, the mesopores are created by the extraction of Al from the zeolite framework, which is responsible for the zeolite acidity. Accordingly, a decrease in the number of acid sites is always observed [77,82]. Still, an increase in the strength of the acid sites is also attained, until a certain level of dealumination is performed.

Desilication

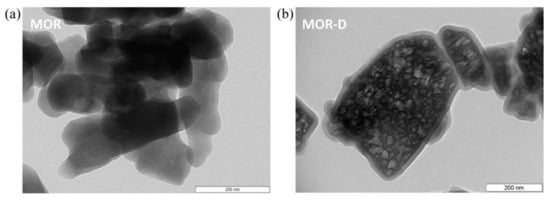

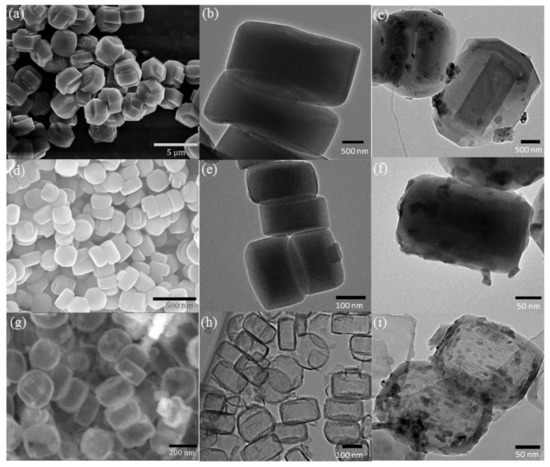

Desilication is an alternative demetallation strategy that consists of the selective removal of Si atoms from the zeolite framework, generally using NaOH as a desilicating agent. This method was first mentioned in the literature with the purpose of modifying the Si/Al ratio of zeolites structures, without significant impact on the zeolite acidity, as opposed to dealumination procedures [83,84]. Nevertheless, the presence of mesoporosity was only mentioned in 2000 by Ogura et al. [85]. The authors submitted ZSM-5 to an alkaline treatment with NaOH solution and reported the presence of mesopores without significant damage of the original microporous structure. In spite of the great amount of research concerning the desilication method being dedicated to ZSM-5 (MFI structure), due to the expressive number of papers and reviews published by the Pérez-Ramirez group [68,69,86,87,88,89], an identical procedure has also been applied to a large number of zeolite structures (see Table 2). For example, MOR structure was subjected to an optimization of the desilication conditions by changing the temperature, base concentration, and duration of the treatment [90]. Figure 9 shows the corrosion of the crystals (lighter zones of the right TEM image) as a consequence of the treatment that leads to the development of mesoporosity.

Figure 9.

TEM images of (a) parent (MOR) and (b) desilicated MOR (MOR-D) zeolites. Reproduced with permission from Reference [90]. Copyright (2013) Elsevier B.V.

The desilication procedures performed over several zeolite structures soon revealed that the experimental conditions used (e.g., NaOH concentration, temperature and duration of the treatment) had different impact, depending on the zeolite structure [70]. It was also found that the Si/Al ratio of the parent zeolite structure is an important parameter to account for desilication treatments. Verboekend and coworkers [69] deeply studied the effect of this parameter and found that for low Si/Al ratios an acid-washing subsequent to the desilication treatment is required, with the purpose of removing aluminum-rich debris to restore the occluded porosity. This effect was observed also in MWW (Si/Al = 13.8) [72] or BEA (Si/Al = 12.5) [73]. On the other hand, for high Si/Al ratios or even in the case of pure silica materials, such as silicalite-1, the addition of organic molecules, such as tetraalkylammonium cations with NaOH, was successfully reported [91,92]. These organic molecules act as “pore directing agents”, PDAs, which partially cover the outer surface of the zeolite crystals, allowing a controlled desilication of the zeolites, preserving their properties, such as crystallinity and microporosity [69]. These organic molecules can also act as “softer desilication agents” when compared with NaOH, allowing one to perform desilication treatments over sensitive zeolites structures, namely BEA, as successfully reported by Holm et al. [71]. An additional advantage of using organic bases as desilicating agents is that the method allows one to combine desilication and ion exchange in only one procedure, whereas a second step of ion exchange is needed after desilication with NaOH to ensure that the final material is in the protonic form.

Desilication treatments in the presence of microwave radiations has also been reported as an effective postsynthesis method to modify the porosity of zeolites and zeotypes. The first study was firstly published in 2009 by Abelló and Pérez-Ramírez [93] where the desilication of ZSM-5 in the presence of NaOH was effectively performed in a few minutes irradiation time. The same methodology was later extended to other zeolite structures such as MOR [75] or MWW [72]. In all cases, hierarchical materials were obtained, and the time needed for the treatments was substantially shortened. However, in some cases, the textural modifications were distinct depending on the heat source: when conventional heating was used an increase in the mesoporous volume was observed whereas on the presence of microwave radiation an enlargement of the microporosity was verified [75].

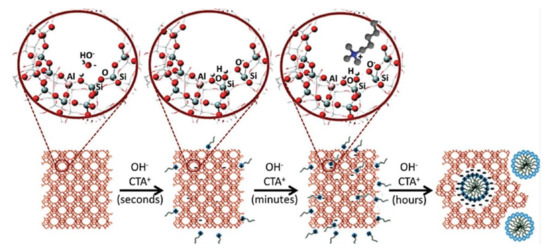

Surfactant-Templated Zeolites

In spite of a high number of publications concerning the effective preparation of hierarchical zeolites through desilication methods, as well as the significant number of well-succeeded catalytic applications, it was also reported that one of the disadvantages of conventional desilication is the poor control of the mesoporosity, that is, the shape, size, connectivity and location of the mesopores, especially in the presence of strong bases such as NaOH [72]. Thus, current trends in the development of hierarchical materials are focused on controlling the mesoporosity through the combination of several methods to tune the hierarchical porosity and related properties of zeolites. An important contribution in this topic was given by Garcia-Martinez and coworkers [94,95,96,97] who proposed that hierarchical zeolites can be prepared by a postsynthesis treatment involving a base and a surfactant. Using optimized parameters of concentration, temperature, time, and pH, the silica dissolution takes place just locally, and the surfactant micelles lead to the rearrangement of the released zeolite subunits into an ordered meso structure, due to a local rearrangement mechanism. This effect was firstly described by Ivanova et al. [98] and, later, by Wang et al. [99], who described the treatment of MOR zeolite using solutions of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and NaOH with different concentrations and observed that, for high base concentrations, the zeolite microporosity was completely removed and replaced by a mesoporous MCM-41 type material. On the other hand, when low base concentration was used, the zeolite recrystallizes, exhibiting both micro- and meso-pores; that is, a hierarchical MOR zeolite was developed. Garcia Martinez et al. [94] applied identical strategy and made a clearer interpretation of the local crystal rearrangement phenomena. By performing a mild treatment to Y zeolite (FAU structure) using NH4OH base solution and CTAB, followed by a hydrothermal treatment, under autogenous pressure. The resulting material presented, not only a higher mesoporosity, but its mesopore size distribution was more uniform, keeping the crystal size and morphology intact (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the different steps involved in the surfactant-templating of zeolites: (i) the hydroxyl groups react with the zeolite network to generate negatively charged sites (Si–O–Si + OH− > SiO− +Si–OH); (ii) the cationic surfactant molecules are attracted inside the zeolite by electrostatic interaction; and (iii) the surfactant molecules self-assemble in micelles inside the zeolite crystals, forming the mesoporosity. Adapted with permission from Reference [97]. Copyright (2020) Wiley-VCH GmbH.

The same strategy has been applied to other zeolite structures, such as MOR [100], BEA, MFI, and LTA [101], as well as the exploration of other surfactants and bases [100,102,103]. Recently, Mendoza-Castro et al. [97] critically reviewed the surfactant-templated methodology, from the optimization of experimental parameters to the extension of this methodology to a large number of zeolite structures, focusing on their use for industrial purposes. In this scope, the most relevant application is the mesostructured Y zeolite as FCC catalysts that is already use on industrial scale by Rive Technology Inc. since 2006 [94,104], but other applications were recently reported, including the synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds through Friedel–Crafts alkylation reactions using surfactant-templated USY [105].

Mechanochemistry

Mechanochemistry is a versatile method to induce several types of transformations on zeolites and related materials, especially milling, which deals with high energy/speed processes. According to the review paper of Majano et al. [106], the precise control of the energy supplied to the materials by the mechanochemical method allows several types of transformations, by the interaction of the solid with the surrounding species. For example, ion exchange or catalysis is favored when low energies are applied. On the other hand, total amorphization or even recrystallization occur in the presence of high energies. The modification of textural properties through mechanochemistry generally occurs when medium energies are applied, leading to the fragmentation and partial destruction of crystal/crystal aggregates. The few examples available on the literature include the wet ball milling of Y zeolite reported by Akçay et al. [107], where the authors highlighted the importance of the operating parameters of the ball mill, such as ball size, milling speed, and time, as well as the presence/absence of solvent. For instance, it was observed that when faster milling speed was applied, smaller particles were obtained, with wider particle size distributions, but the crystallinity was hardly affected. On the other hand, using a small ball diameter, very small particles were obtained after a long milling time, with narrower pore size distribution. Finally, the presence of solvent resulted in high crystalline material when compared with dry ball milling performed under the same conditions. Hernandez-Ramírez et al. [108] described the synthesis of hierarchical Y zeolite–carbon composites using a new seeding technique based on milling carbonized olive seeds and coconut fibers coupled with commercial Y zeolite. More recently, Ferreira et al. [109] modified SAPO-11 zeotype through ball milling aiming to modify their textural properties by optimizing the milling time. The authors found that after 60 min milling a partial destruction and disaggregation of the crystal aggregates is optimized leading to an increase in the external surface area but keeping the acidity properties. This allows one to improve the catalytic behavior of SAPO-11 based materials since the access of the reacting species to the pore openings of SAPO-11 structure is improved.

Delamination and Pillaring

Layered materials are made of a consecutive repetition of individual layers or sheets located in parallel spatial planes, bonded through electrostatic interactions (van der Waals or hydrogen bonds). These open structures, with high surface area, are constituted by crystalline ordered (pillared zeolites) or disordered (delaminated zeolites); however, it must be mentioned that the application of these methods is not restricted to zeolite and zeotypes but is also successfully applied to other types of materials, namely clay minerals.

The pillaring process is known for a long time due to its application in clays, hydrotalcites and other inorganic lamellar materials and consists of the permanent covalent-type intercalation of materials with organic inorganic or the combination of them into the interlayer space. The process allowed one to considerably increase the surface area of the pristine material due to the creation of a bidimensional pore system upon the intercalation of the pillaring species (e.g., Kegin type cation [AI1304(OH)(24+x)(H2O)(12−x)](7−x)+) followed by calcination to obtain stable pillars. Even though nowadays these materials continue to be explored, the greatest number of studies based on pillared-clays immobilized complexes dates from the beginning of this century [110,111]. More recently, some application for zeolites has been reported. Accordingly, the materials possess their native microporosity and additional porosity obtained by the expansion of the layers that can be customized depending on the size of the pillars. The first and most cited example of pillared zeolitic material is MCM-36, which is obtained from the intercalation of MCM-22 precursor [112]. The preparation of this material follows the classic protocol that includes an initial swelling step through cationic exchange with alkyl-ammonium species (C16TMA+OH−), which are placed in the interlayer space. Secondly, the swollen precursor is pillared in an inert atmosphere using tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), which is finally hydrolyzed, and then, in a final step, the sample is calcined to decompose the surfactant and obtain stable pillars, that expand permanently, originating intercrystalline mesoporosity between the layers [113]. Following the same methodology, Liu et al. [114] synthesized Sn-MCM-56, obtained from delaminated Sn-MWW and found significant improvements to the diffusion of bulky molecules when compared in the presence of microporous zeolites. The use of this method to produce other pillared zeolite structures is rather scarce. An example using the MFI structure was reported by Na et al. [115] who reported the successful pillarization without the swelling step to obtain a 3-D ordered hierarchical MFI structure, where the diameter of the mesoporous formed can be easily controlled according to the surfactant tail length. In addition, concerning the pillarization of MFI structure, Zhang et al. [116] described a process of three-dimensional nanosheet assembly by the repetitive branching of orthogonally connected nanosheets of MFI. The house-of-cards type of rearrangement of the nanosheets creates a permanent network of mesopores with 2–7 nm, along with a high surface area with great potentialities for catalytic applications involving bulky molecules.

In opposition to pillared materials, delaminated zeolites are made of disordered layers. Thus, the mesoporosity is obtained from the random stacking of these layers. The delamination process involves the treatment of the zeolite precursor with an alkaline solution in the presence of surfactants to expand the interlayer distance. Then, the suspension is submitted to sonication to promote the complete separation of the layers and, finally, the delaminated material is calcined to remove the surfactant. Inside the family of delaminated zeolites, ITQ-2 was the first and still the most cited delaminated material [117]. The preparation method comprises the swelling and exfoliation of MCM-22 precursor and individual layers of about 2.5 nm of thickness, with a high external surface area of more than 700 m2 g−1 being obtained. Examples of other delaminated materials referred to in the literature are ITQ-6 [118] and ITQ-18 [119], obtained from FER and NU-6(2) precursors, respectively.

Despite delamination and pillaring being effective strategies to obtain hierarchical structures, with some proven catalytic applications, the scale-up production of these materials is still challenging due to the high costs of the surfactant used. In addition, the significant loss of material that occurs, especially during the delamination process, because of the high surfactant content and alkalinity used that leads to the dissolution of the zeolite structure, is also a drawback when compared to other strategies to produce hierarchical materials.

3.2. Mesoporous Silicas and Composite Hierarchical Materials

Mesoporous molecular sieves (MMS) are characterized by high surface area (800–1400 m2 g−1), large pore volumes, and tunable pore dimensions (2–50 nm). The arrival of the first member of the M41S family in 1991, designated as MCM-41 [120], carries great expectations for possible applications of these materials in catalysis and adsorption, overcoming the limitations of zeolites due to their intrinsic microporosity. Later, other related mesoporous silica materials, namely MCM-48, MCM-50, and SBA-15, were synthesized [121]. Recently, more robust mesoporous silica materials have been presented, such as, TUD-1 [122], FDU-12 [123], or KIT-6 [124]. However, despite MMS materials possessing large pores when compared to zeolites, which allows for improving molecular diffusion, and some improvement on the stability having been attained in the last years, their lack of acidity hinders the application of these materials to a wide range of catalytic reactions, when compared with traditional zeolites [121], limiting their use mainly as catalyst supports.

Composite materials are characterized by a mixture between a zeolite, which contributes to its characteristic microporosity, and another material that must be porous itself, or alternatively, contributes to the generation of intercrystalline porosity due to particle stacking. Schwieger et al. [25] reviewed several combinations of composite materials: the simplest approach is the shaped zeolitic bodies, comprising the mixture of a powder zeolite with a binder material, that, after compacting and shaping operations, originates pellets, beads, cylinder, etc., with interparticle macropores on the packed bed level, when used as reactor/column filling. More technological approaches include coating strategies where a support surface is functionalized with a zeolitic material, originating hierarchically organized materials with two or three levels of porosity. The preparation of these materials can be performed according to two strategies: ex situ coating where a layer of a presynthesized zeolite is deposited on a support such as alumina foams [125] or cordierite monoliths [126] and in situ coating comprising the direct hydrothermal synthesis of a zeolite on a support surface. In this later case, the supports can be classified as inert or reactive: in the first case, the crystallization of the zeolite takes place at the external surface of the support keeping it unchanged [127], but on the other hand, in the presence of reactive supports such as SiO2 or Al2O3, a fraction of the support is consumed with consequent incorporation and intergrowth between the zeolite layer and the residual support material [128,129]. Recently, the combination of a microporous zeolite with a mesoporous material has gained much attention, comprising a core–shell system where the core is made of zeolitic microporous material surrounded by a mesoporous shell. These composite materials combine two organized pore systems: a microporous zeolite containing the active sites enwrapped in a mesoporous material with large transport channels, leading to an improvement on both catalytic and adsorption behavior. Examples of core–shell materials can be found on the literature using several zeolite structures such as MFI [130,131] FAU [132], and MWW [133] enwrapped by mesoporous molecular sieves such as SBA-15 and MCM-41, bringing a new opportunity for the application of these mesoporous molecular sieves.

4. Immobilization Methodologies

4.1. Complexes

Several methodologies can be used to immobilize metal complexes on solid supports and a possible systematization can be made considering the type of complex–support interaction: (i) covalent bonding; (ii) physical adsorption or electrostatic interaction; and (iii) encapsulation.

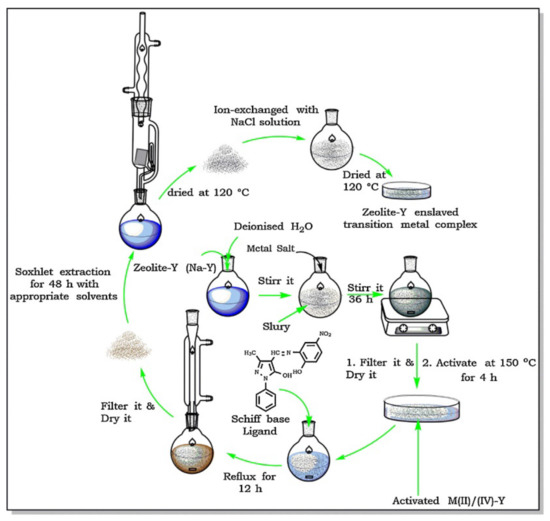

When zeolite structures are used, encapsulation by flexible ligand method is a quite common synthesis methodology. This “ship-in-a-bottle” strategy is basically a two-step process that takes advantage of the ion exchange properties of zeolites and of their pore network characteristics, namely the presence of large cavities accessible through windows narrow enough to hinder complex leaching, which explains that FAU structures are specially suitable to prepare immobilized catalysts by this method and are in fact those selected for this purpose [14,15,16,18]. The scheme reproduced in Figure 11 was presented by N.C. Desai et al. [16] to illustrate the preparation of several metal complexes immobilized on Y zeolite by the flexible ligand method. Catalyst preparation starts with the ion exchange of the as-synthesized zeolite (Na-Y) with the metal salt, to obtain what is designated in scheme by M(IV)/(II)-Y, being M = Fe, Co, Ni, etc. The exchanged solid is then made to react with the ligand—in this study, a Schiff base, refluxing the mixture to promote the complex synthesis. The catalyst is then washed by Soxhlet extraction, back-exchanged with a NaCl solution to eliminate uncoordinated metal, and finally washed and dried. The complex formed inside the Y zeolite supercages is too bulky to spread out so it cannot leach into the liquid phase during the catalytic assay. On the other hand, the space available inside the 1.3 nm diameter large cavity of the Y zeolite is enough to accommodate the complex and to allow the diffusion of substrates and products no larger than 0.74 nm, i.e., the pore opening value. The catalysts prepared proved to be active for styrene oxidation and in the case of the best performing catalysts reuse tests shown that a short fall in the activity was observed only in the second cycle, attributed to the leaching of a small fraction of the immobilized complex, which was not observed in subsequent reuse cycles.

Figure 11.

Scheme of the experimental procedure to encapsulate complexes on Y zeolite by flexible ligand method. Reproduced with permission from Reference [16] Copyright (2016) Elsevier B. V.

Other types of structures imply other synthesis approaches such as, for example, covalent bonding or electrostatic interaction that are widely used when large pore solid supports, such as mesopore silicas, are considered. To apply this synthesis methodology, it is necessary that the solid surface has functional groups that can react with the complex (either with the metal or with the ligands) during the immobilization, which is promoted by refluxing the mixture support-complex, typically overnight. The final steps are the usual washing and drying processes [74,100].

The catalysts obtained by this method have leaching as their main disadvantage, which can attain values as higher than about 50%, as reported in the study where Fe-scorpionates immobilized of NaOH treated MOR were tested for cyclohexane oxidation [90]. This result was interpreted as indicative of an electrostatic interaction of the complex with the support.

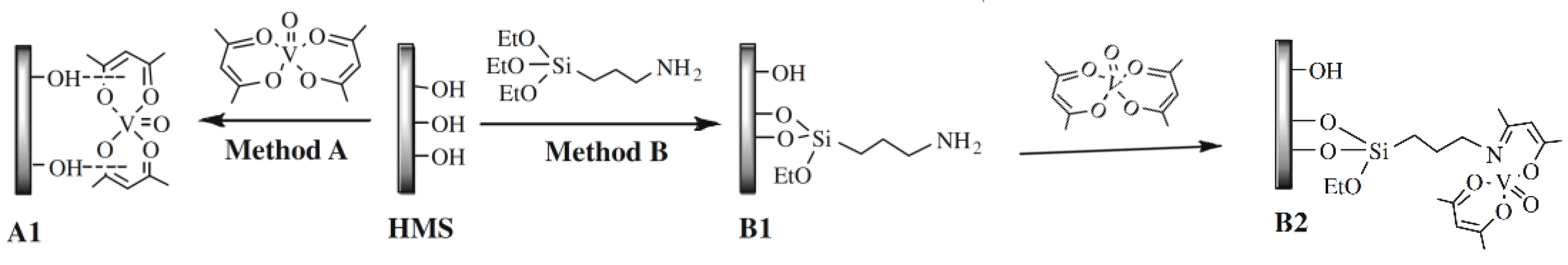

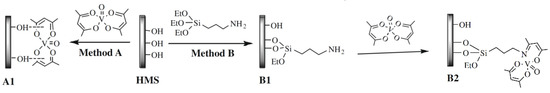

On the other hand, as consequence of the immobilization, the electronic structure of the homogeneous catalysts is modified, and consequently, its performance is not the same as that of the homogeneous counterpart. This is clearly shown by the results reported by Jarrais et al. [134] for [VO[acac)2] immobilized on a ordered mesoporous silica (HMS). The catalysts were tested for geraniol epoxidation, and while the homogenous assays resulted in a total conversion of the substrate after 1h of contact time, when the catalyst obtained by direct immobilization (method A in Figure 12) was used, only 17% of substrate conversion was obtained after 48 h of reaction. To overcome this disadvantage, it is common to consider the use of a linker, that is, a molecule that has a moiety that forms a covalent bond with the support and a moiety that can coordinate with the complex (either with the metal or with the ligand), which is then immobilized. This approach was also followed by Jarrais et al. [134] to prepare catalyst B2 using APTES (3-aminopropyl- triethoxysilane) as a linker. In this case, there are more preparation steps, since the synthesis starts with the solid functionalization with the linker, after what the modified solid support is then refluxed with the solution containing the complex. The more elaborated synthesis process resulting in a much better catalytic performance than that of material A1, since after 48 h a total conversion of geraniol was attained not only with the fresh catalyst but also in the fifth reuse cycle.

Figure 12.

Methodologies for [VO(acac)2] immobilization onto HMS materials. Adapted with permission from Reference. [134] Copyright (2009) Elsevier B. V.

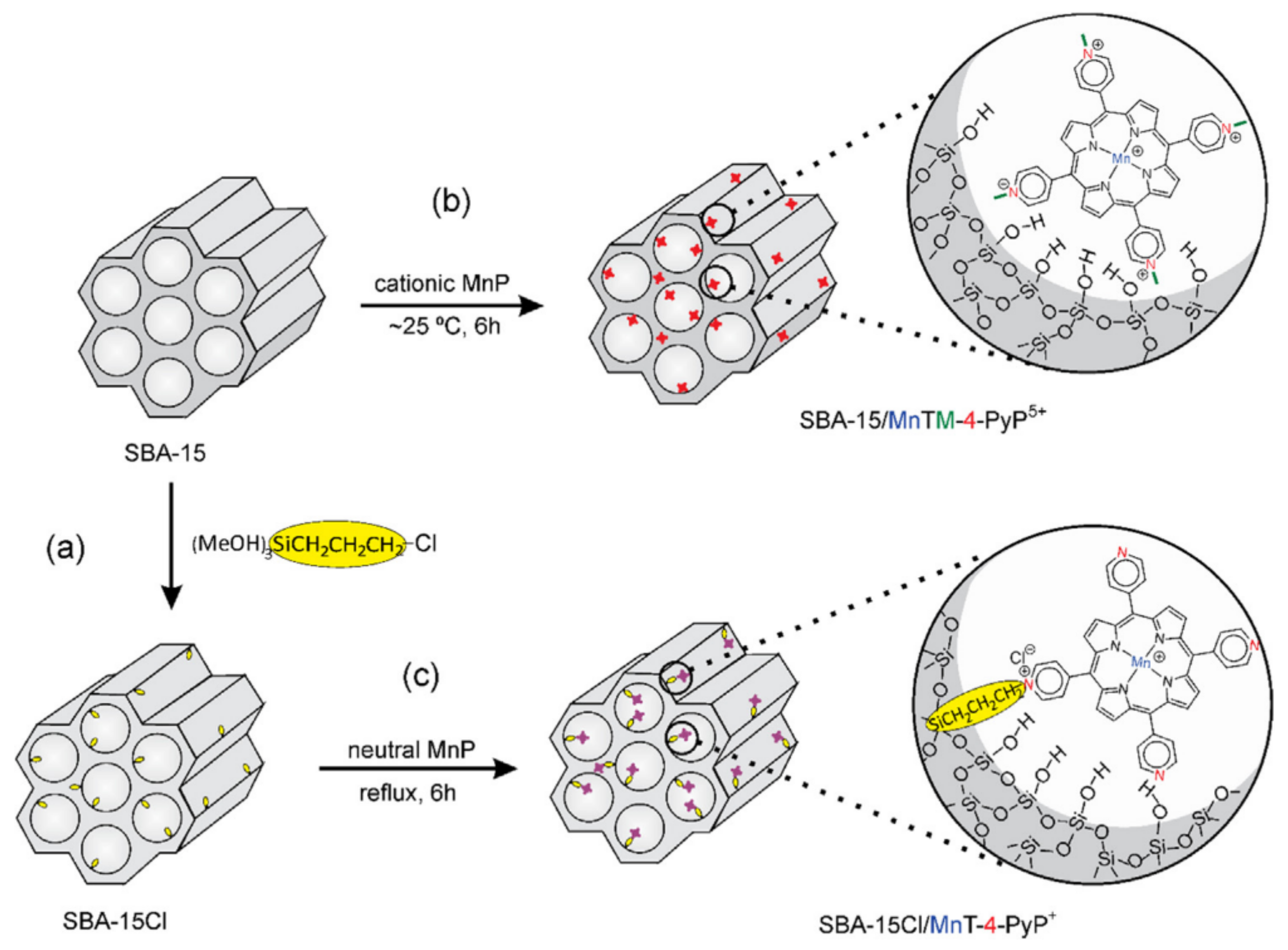

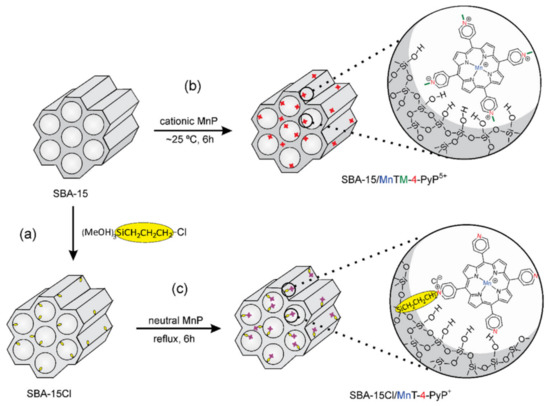

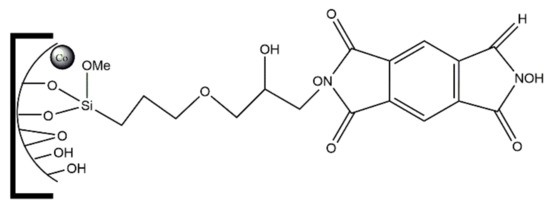

Another example of how the abundance of Si-OH surface groups of HMS are used to immobilized organometallic complexes using a linker is provided by Pinto et al. [135]. These authors used ordered mesoporous silica SBA-15 and its correspondent chloropropyl-functionalized silica (SBA-15Cl) as supports for immobilization of different neutral and charged Mn porphyrins (MnP) (Figure 13). The resulting MnP-supported materials with MnP loadings of 0.3% w/w were obtained in these materials, and the heterogenized systems SBA-15/MnTM-X-PyPCl5 and SBA-15Cl/MnT-X-PyPCl (X = 2, 3, 4) and nonimmobilized neutral MnP isomers were successfully evaluated as catalysts for cyclohexane oxidation using iodosylbenzene (PhIO) as oxygen donor, as is discussed in Section 5.

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of the synthetic routes for (a) preparation of support SBA-15Cl by the silanization of SBA-15 with CPTS, (b) immobilization of MnTM-4-PyPCl5 on SBA-15 by electrostatic interaction, and (c) anchorage of MnT-4-PyPCl on SBA-15Cl by covalent bonding. The two classes of heterogenized catalysts are illustrated with the para MnP isomers. Reproduced with permission from Reference [135]. Copyright (2016) Elsevier B.V.

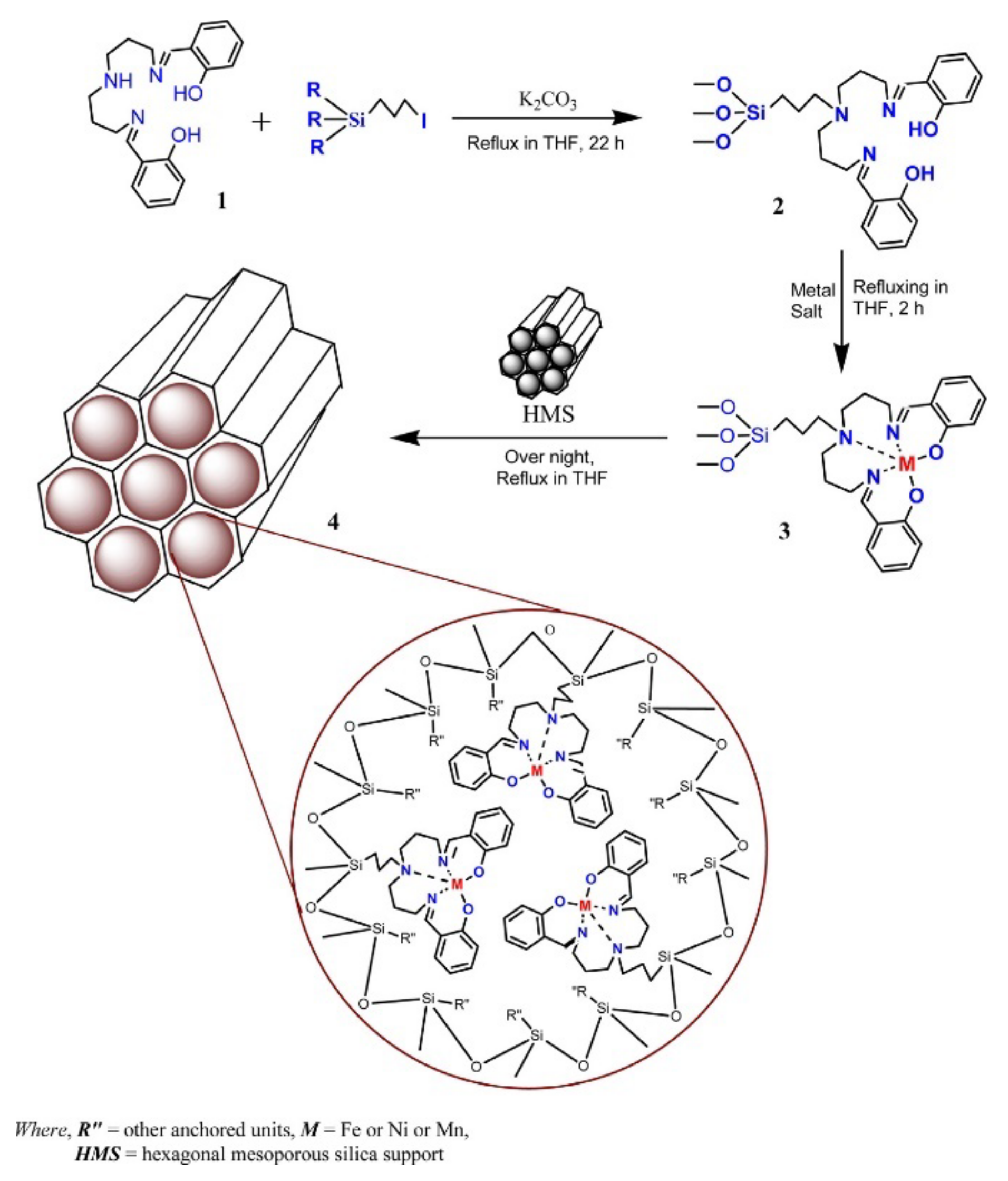

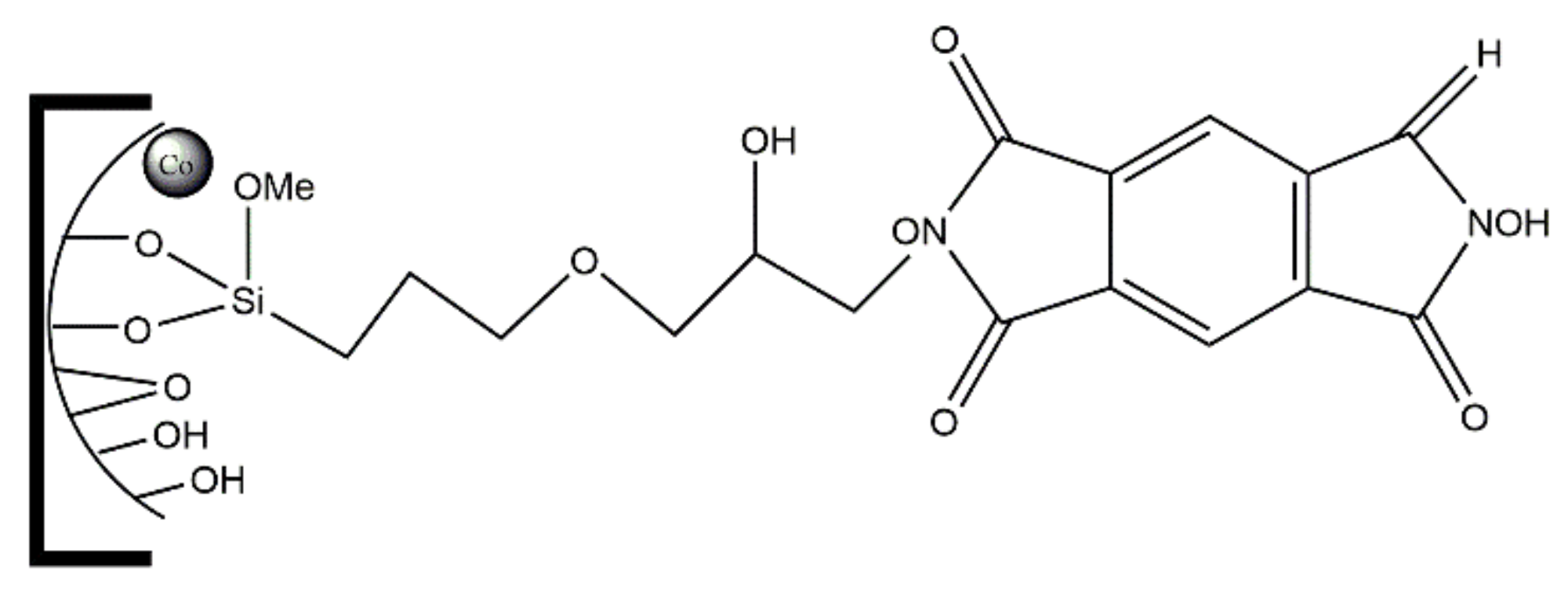

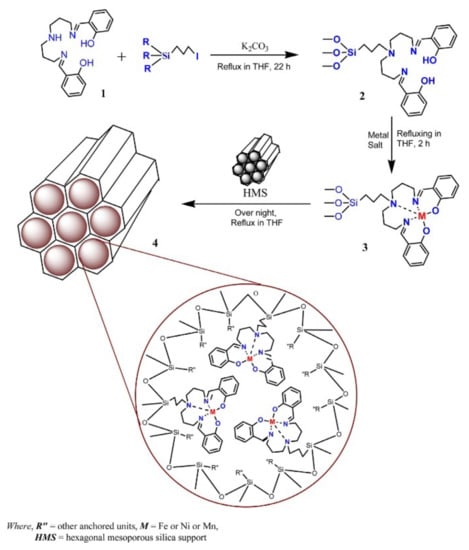

A different approach for the immobilization by covalent bonding with a linker is illustrated in the scheme in Figure 14, reproduced from the study by Machado and co-workers [136]. In this work the linker reacted with the ligand (step 1) that was further used in the complex synthesis (step 3). During the reflux of the complex solution with the mesopore silica HMS (step 4), the linker reacted with surface groups of the support leading to the immobilization of the complex. This procedure minimizes the changes in the electronic structure of the homogeneous catalysis and eventual constraints due to the solid surface proximity.

Figure 14.

Scheme of the experimental procedure to immobilize Fe, Ni, or Mn complexes on HMS–hexagonal mesoporous silica though covalent bonding. Reproduced with permission from Reference [136] Copyright (2013) Elsevier B.V.

Even though in the literature, there are examples of immobilization by covalent bonding with a linker with various materials, namely carbon materials [137,138], inorganic solids like clays or clay-derived materials [134,139,140] and especially silicas are actually the most currently used supports when this immobilization process is envisaged due to the high amount of hydroxyl surface functionalities of these materials [111,135].

Lastly, it must be noted that the longer reaction time needed when immobilized catalysts in porous materials are used is a common result due to the presence of diffusion steps which are not present in homogeneous assays.

4.2. Metal Particles

The immobilization of metal particles in zeolites and other porous materials can be made by two distinct strategies: postsynthetic methods and confinement during synthesis. In the first case, the metals are introduced after the complete synthesis of the zeolite framework, whereas the second method deals with the co-crystallization of the zeolite and the metal precursors, followed by an in situ reduction to obtain the metal particles [19].

The postsynthesis immobilization is simple and widely used. It deals with contacting the support with a solution containing the soluble metal precursor and can be made by two methods [141]: (i) using an excess of solution (ion exchange) [142,143] or (ii) using the minimum amount of solution needed to fill the porosity of the material (incipient wetness impregnation) [144,145]. Upon these procedures, the material is dried and submitted to a thermal treatment in the presence of hydrogen to promote the reduction of the metal precursors into its active state, where special care should be taken during this procedure to avoid metal sintering. To avoid this step, an alternative method comprising the contact between two solids can be performed. In this case, the zeolite and the inert support containing the dispersed metal are put in contact through mechanic mixing using a simple mortar or, more sophisticatedly, a ball mill to allow an improved contact between the two solids [30,109,146].

In pure microporous zeolites, the dimension of the confined metal particles is restricted to a few nanometers, that is, limited by the dimension of the pores [147]. In the presence of small size metal particles, their diffusion is allowed inside the pores; even so, this is only facilitated in the presence of large pore zeolite structures such as BEA, MOR, or FAU, where the metal particles can be encapsulated inside the pores. For larger particles or in the presence of medium to small pore zeolites, a large amount of metal is restricted to be fixed to the external surface of the zeolite crystals.

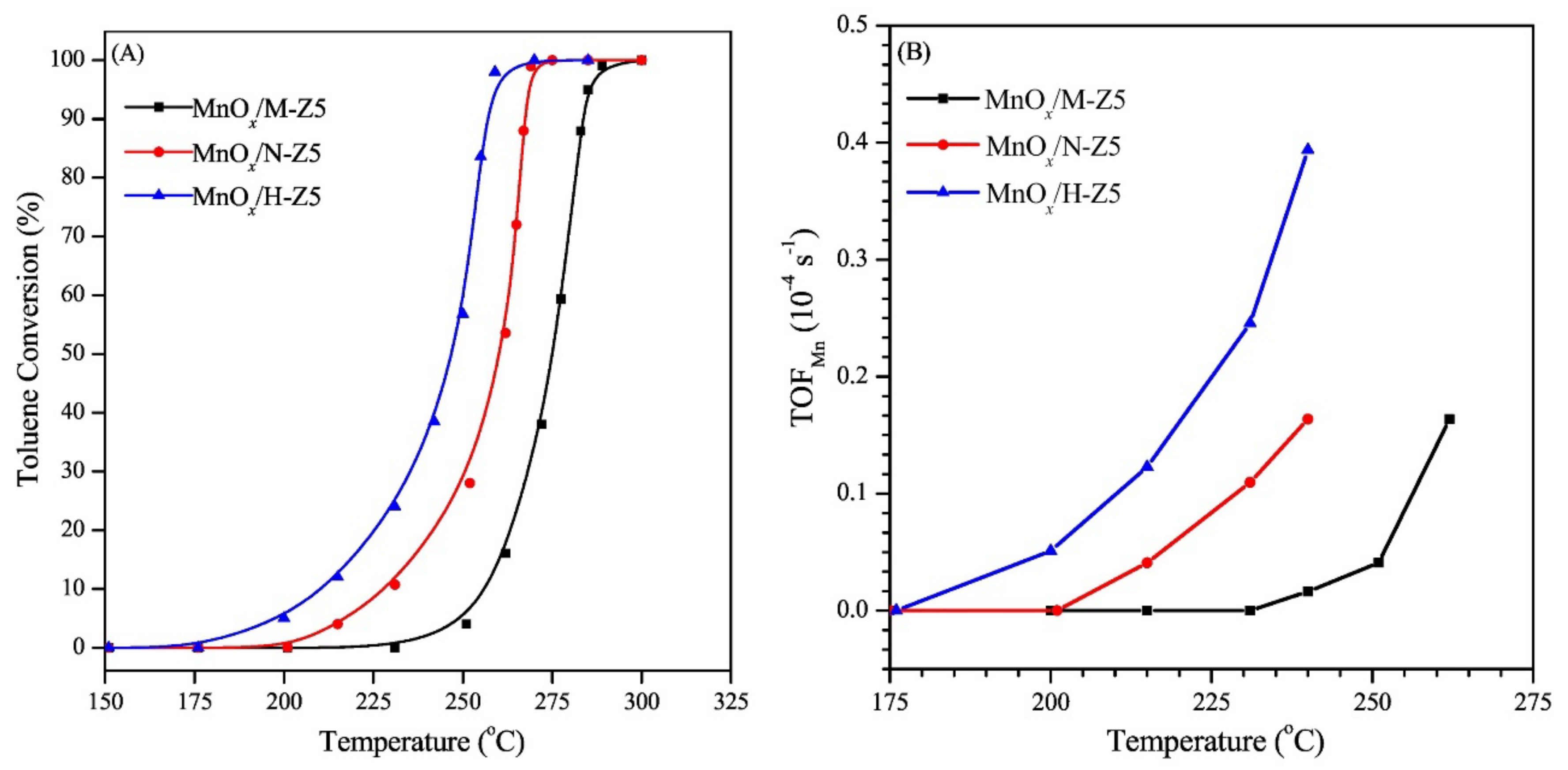

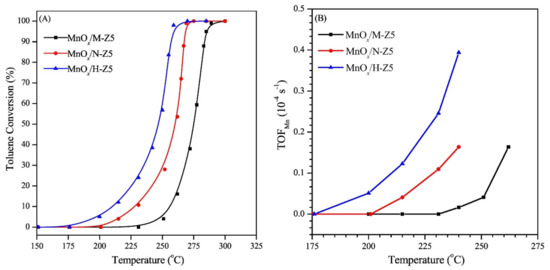

To overcome this limitation, the use of supports with hierarchical porosity has been revealing promising results. For instance, Wang et al. [148] reported what they called a “fish in the hole” strategy to trap Pd nanoparticles in FAU, BEA, and MFI zeolite structures. The authors performed a thermal treatment at 700 °C for a slight dealumination to create “traps” with diameter of 20–30 nm. Upon mixing the Pd precursors with the “trap”, rich zeolite and further heat treatment, the metal particles became confined at the “traps”, preventing the metal aggregation, even under harsh thermal conditions. In another study, hierarchical MOR was prepared through alkaline treatments followed by acid treatment, originating an effective support for the introduction of Pt nanoparticles [149]. The Pt loaded on hierarchical MOR showed superior metal dispersion when compared with the pristine microporous MOR, giving superior catalytic performance for toluene combustion and long-term stability (60 °C) making this material a promising catalyst for real application in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) control.

Metal sites can also be introduced inside zeolite crystals during synthesis. In this case, as-synthesized metal particles or soluble metal precursors are mixed with the zeolite synthesis gel. Upon the crystallization step, the material is calcined to remove organic species and reduced under hydrogen atmosphere to form the metal sites [55,57].

An important issue to successfully confine metal particles during the synthesis is to accomplish an adequate balance between the simultaneous crystallization of both the zeolite and the metal clusters to obtain a homogeneous dispersion and size of inside the zeolite crystals. To achieve this goal, a judicious choice of the experimental conditions of the synthesis (e.g., alkalinity, silica source), as well as the type of metal or metallic precursor, is mandatory [19].

5. Catalytic Applications

This section presents the catalytic applications of coordination compounds or metals particles immobilized at inorganic supports whose synthesis/modification was described in Section 3.

Among commercial zeolites, FAU structure is the most cited material used as catalyst support. This can be explained by the presence of large supercavities in its structure that can accommodate large species. The introduction of mesoporosity in zeolites, leading to the so-called hierarchical materials (see Section 3.1), as well as the use of purely mesoporous materials (see Section 3.2) allowed one to overcome the accessibility limitation of commercial zeolite and triggered the applications of these porous materials as catalytic supports. Representative examples are summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, and relevant examples follow.

Table 3.

Catalytic applications of commercial/hierarchical zeolites and other related materials as catalysts support for oxidation of alkanes.

Table 4.

Catalytic applications of commercial/hierarchical zeolites and other related materials as catalyst supports for oxidation of alkenes.

Table 5.

Commercial/hierarchical zeolites and related materials applications as catalytic supports for the oxidation of aromatics.

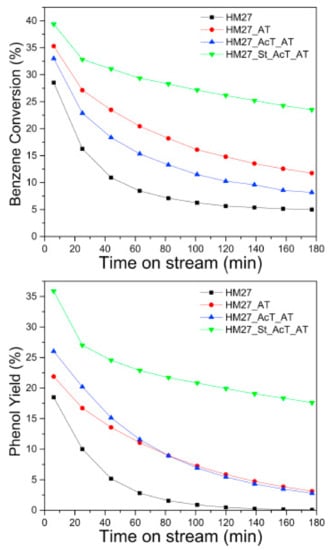

5.1. Oxidation of Alkanes

Reports on the oxidation of alkanes are scarce due to the low reactivity of this class of hydrocarbons. The most relevant reactions are the synthesis of maleic anhydride from n-butane and, by far, the oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone. The homogeneous oxidation of cyclohexane is highly important due to the industrial relevance of its products. In fact, as explained in detail in Section 1, the mixture of cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone is an intermediate in the synthesis of nylon-6 and nylon-6,6. However, the current industrial catalysts lead to very low cyclohexane conversions to achieve moderate selectivities. Thus, the large number of papers concerning metal catalysts immobilized in several supports devoted to this reaction is not surprising (see Table 3). Selected examples are discussed in more detail ahead.

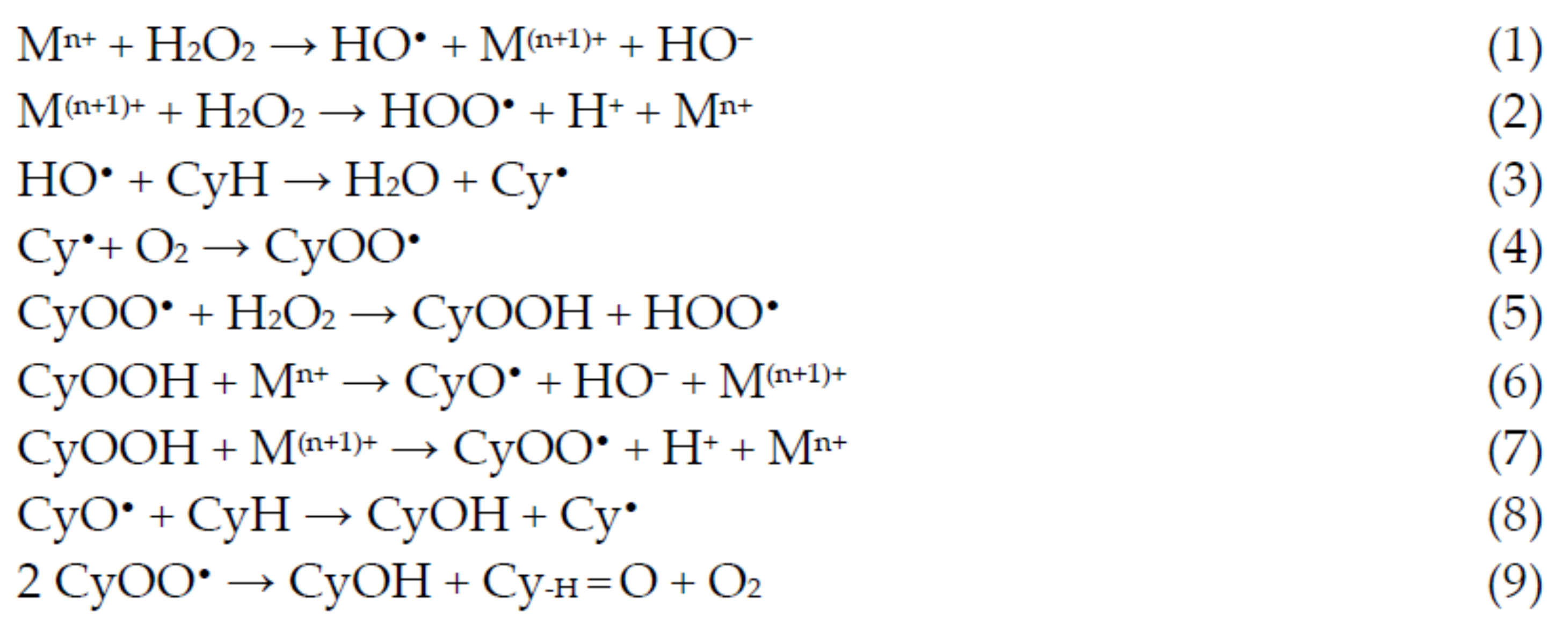

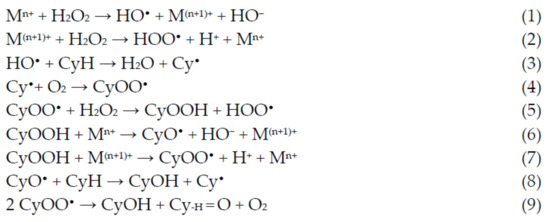

An alternative to the industrial process that has been explored in the last years is the room temperature oxidation, using peroxides instead of dioxygen (for example, using its formally equivalent, hydrogen peroxide). This oxidation occurs through the formation of cyclohexyl hydroperoxide (CyOOH) as the primary product, which further evolves into the mixture of cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone (see Figure 2, Section 1). Several experiments and theoretic calculations revealed that the reaction should proceed through free-radical pathways, where the catalyst does not interact directly with the substrate but instead with the oxidant (reactions 1 and 2, Scheme 2), forming radicals such as the hydroxyl which, in turn, abstracts one hydrogen atom from the cyclohexane (reaction 3, Scheme 2), starting the propagation chain that leads to the desired products, cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone (reactions 8 and 9, Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Radical mechanism accepted for the catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone.

In a significant number of publications, Y zeolite (FAU structure) is used as support, as its characteristic supercages allow the immobilization of bulky active species (mainly complexes). For example, Chetan and coworkers [151] described the successful synthesis of Y zeolite entrapped transition metal complexes of general formula [M(SFCH)·xH2O]-Y [M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni (x = 3) or Cu (x = 1); H2SFCH = (E)-N′-(2-hydroxybenzylidene)furan-2-carbohydrazide] by flexible ligand method as evidenced by several characterization techniques including inductively coupled plasma/ optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), elemental analyses, (FT-IR, electronic and X-ray diffraction) spectroscopic studies, low-temperature N2 adsorption, and SEM. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were also performed to address the relaxed geometry, bond angle and length, dihedral angle, highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap, and electronic density of states of H2SFCH ligand and its neat transition metal complexes. It was concluded that complexes [M(SFCH)·xH2O] are suitable in size for the zeolite channels, which confined the complex and restricted it from coming out of the supercages of Y zeolite. The catalytic activity of [M(SFCH)·xH2O]-Y for the liquid-phase oxidation of cyclohexane by hydrogen peroxide was evaluated. Among the tried metals, [Cu(SFCH)·H2O]-Y catalyst exhibited the highest conversion (45.1%) and selectivity (84.5%), which agrees with the calculated HOMO–LUMO gap and Fermi energy (higher for the copper complexes). The effect of encapsulation on the stability of [Cu(SFCH)·H2O] was assessed through recycling experiments of [Cu(SFCH)·H2O]-Y. The conversion of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone on first (43.6%) and second (42.3%) reuses of the catalyst was marginally reduced compared with the obtained in first cycle (45.1%), which may be due to some blockage of the zeolite channels during the first cycle.

The use of hierarchical supports has been reported in recent years, where the mesoporosity created through several strategies is considered a positive effect to improve the anchorage of catalytic active bulky species and prevent their leaching during consecutive cycles.

An illustrative example is the anchorage of the C-scorpionate iron(II) complex [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] (pz = pyrazol-1-yl) on a commercial (MOR) or desilicated (MOR-D) mordenite zeolite modified through a classic alkaline treatment with NaOH, reported by Martins et al. [90]. The catalytic behavior of the immobilized iron(II) complex for the oxidation of cyclohexane by hydrogen peroxide (30% aqueous solution) in a slightly acidic medium was evaluated. The metal content, quantified by ICP, of the immobilized [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] at the desilicated support ([FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@MOR-D) was 0.28%, whereas in the case of the commercial zeolite, ([FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@MOR) was 0.40%. Thus, it appears that, under the experimental conditions used for the desilication of MOR support, some of the surface active sites were lost, affecting the interaction of the iron(II) complex with the zeolite. However, the desilication treatment promoted a significant development of mesoporosity along with a small reduction of the microporous volume. This indicates that the mesoporosity results mainly from the corrosion of the external surface of the crystals, leading to the development of intercrystalline mesoporosity, along with some decrease in the microporous volume. Complex immobilization led to an important decrease in all the textural parameters of the zeolitic supports, indicating that the voluminous complex is mainly immobilized at the intercrystalline mesoporosity created during the desilication procedure.

The hybrid material [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@MOR-D provided a noticeable catalytic activity (TONmax = 2.90 × 103) for the selective oxidation of cyclohexane leading to an overall (cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone) yield of 38% after 10 h reaction at room temperature. Thus, the desilicated support allowed the existence of the Fe(II) complex in the intercrystalline mesoporosity of the modified zeolite and originated a significant enhancement of the accessibility of the reactants, leading to a superior catalytic activity. Moreover, [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@MOR-D was easily recovered from the reaction medium and reused. However, only 54% of its initial catalytic activity was preserved after the first reuse run, indicating the occurrence of leaching during the catalytic reaction or the catalyst recovery process and a weak type of electrostatic interaction between the complex and the support.

A more sophisticated postsynthesis treatment to obtain hierarchical zeolites with an accurate control of the size and shape of mesopores is the surfactant templated methodology, where the zeolite is submitted to an alkaline treatment in the presence of a surfactant, under autogenous pressure, as discussed in detail above (see Section 3.1.2). Van-Dúnem et al. [100] applied this postsynthesis methodology to Y zeolite using several alkaline agents (NaOH, NH4OH and TPAOH) in the presence of CTAB surfactant. The obtained materials present a hierarchical structure with enlarged micropores (supermicropores, especially when TPAOH and NH4OH were used) and mesopores, preserving most of the original microporosity.

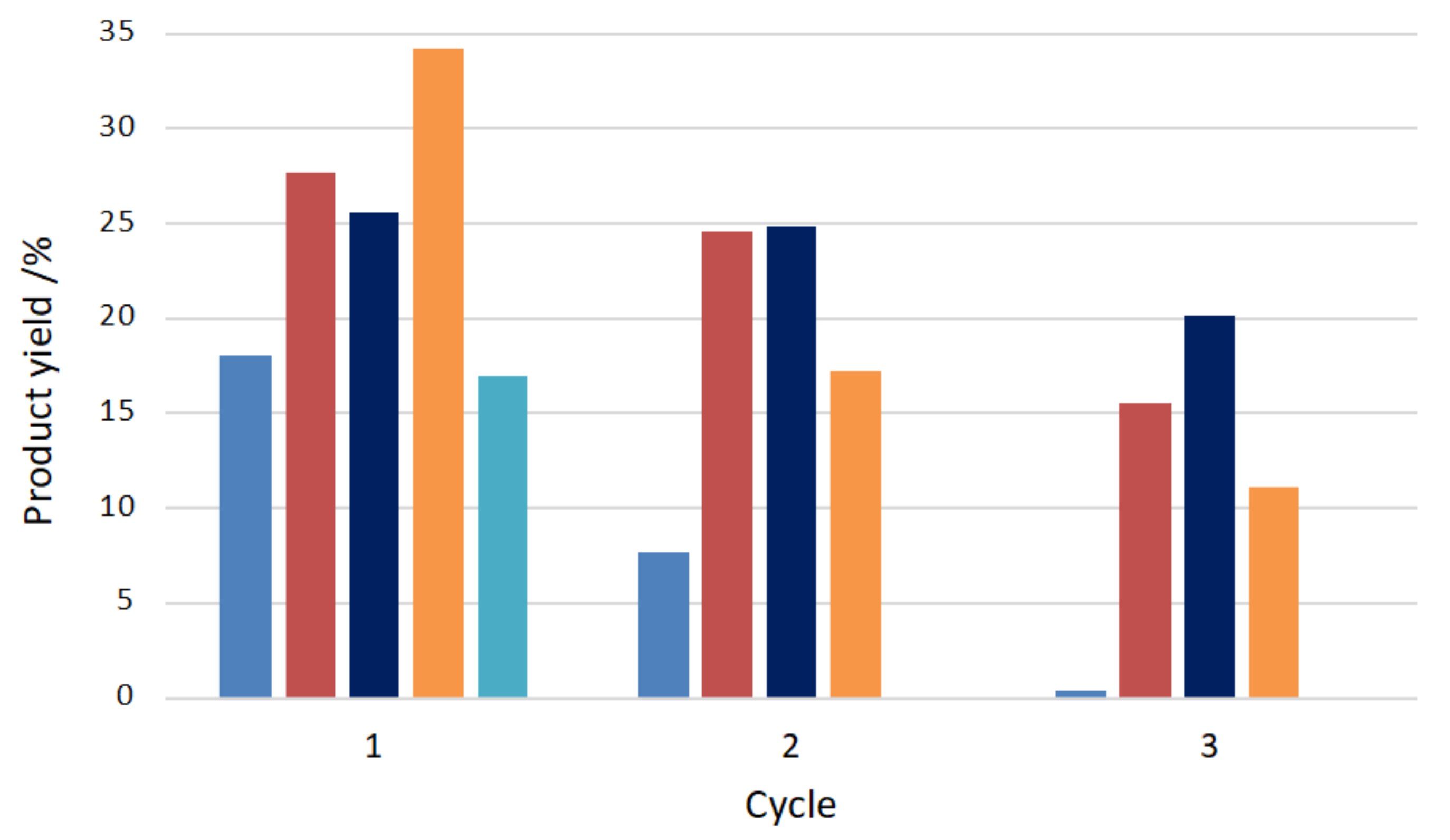

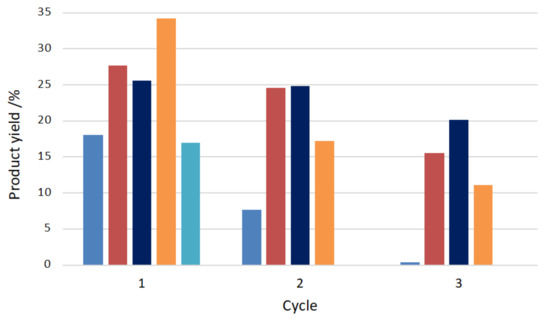

The anchorage of the C-scorpionate iron(II) complex [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] at the above hierarchical materials ([FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y, [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NaOH, [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NH4OH, and [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_TPAOH) led, in all the cases, to a slight reduction of the characteristic microporosity of the zeolitic structure. The authors observed that the effect of the immobilization on larger porosity (supermicropores) for samples [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y and [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NaOH was minimal (porosity values identical to the exhibited by the zeolitic supports), indicating that [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] should be dispersed on the outer surface of the crystals. However, for the supported catalysts [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NH4OH and [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_TPAOH at least a fraction of the iron(II) complex should be located inside the supermicropores and narrow mesopores. The catalytic performance of the prepared hybrid materials was tested toward the oxidation of cyclohexane by hydrogen peroxide at room temperature for 24 h. Yields of cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone up to 34% were attained with concomitant turnover numbers (TONs) up to 271. The hybrid catalysts were easily recovered from the reaction medium and reused in three consecutive catalytic cycles (Figure 15). Their performance appeared to be related with the porosity differences observed in the hierarchical materials. When the complex anchorage occured mainly at the outer surface of the support ([FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y and [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NaOH), high leaching after the first catalytic cycle was observed. The location of a fraction of the iron(II) complex inside the zeolite supermicropores and narrow mesopores favored catalysts recyclability, especially in the case of [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NH4OH. The predominance of the Fe(II) oxidation state on the recycled catalysts was detected by XPS, in agreement with the regeneration of the initial oxidation state of the catalysts in the proposed mechanism of cyclohexane oxidation (see Scheme 2).

Figure 15.

Effect on the products yield of cyclohexane oxidation of the anchorage of the C-scorpionate iron(II) complex [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] at the Y zeolite hierarchical materials: ■—[FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y, ■—[FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_TPAOH), ■—[FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NH4OH, ■—[FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@Y_NaOH, and ■—[FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}] [100].

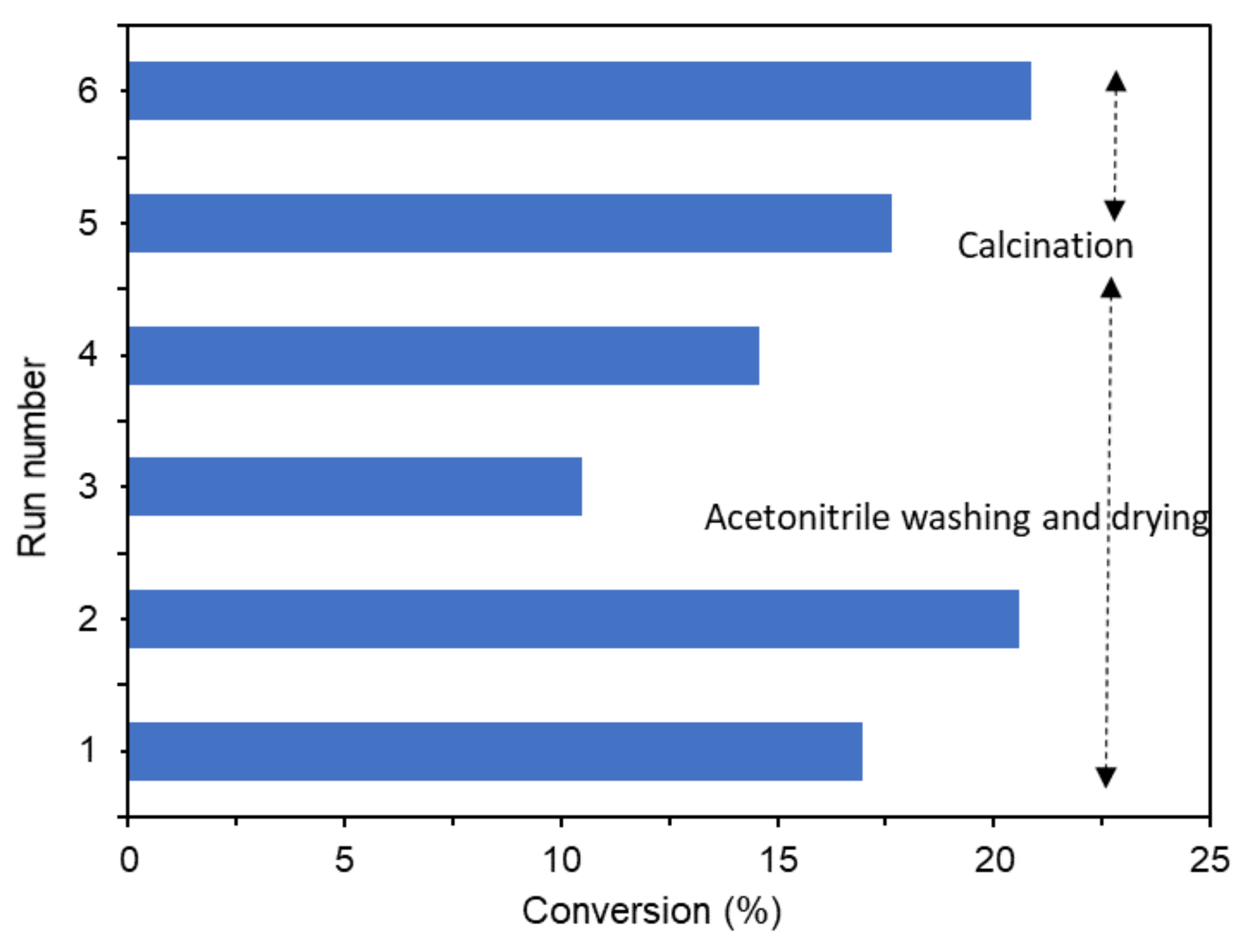

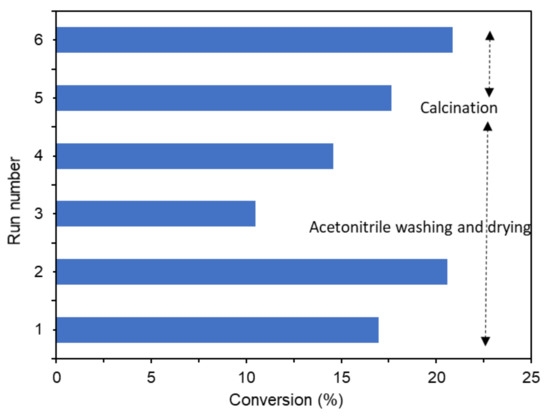

More recently, another work addressing this topic was reported by Ottaviani et al. [103], where MOR zeolite was modified by using NaOH and TPAOH in the presence of CTAB surfactant. The hierarchical zeolite support was used to immobilize the B-scorpionate dioxido-vanadium(V) complex [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}] (pz = pyrazol-1-yl), affording three hybrid catalysts: [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR, [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR_NaOH, and [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR_TPAOH. As expected, the alkaline-surfactant treatment provided a mesopore network, along with a significant change in the textural characteristics of the materials, especially when the strongest base NaOH was used. The vanadium-loaded zeolitic material [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR_NaOH performed as an efficient catalyst for the oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone using TBHP (70% aq. solution), at room temperature, in a slightly acidic medium. A maximum overall yield of 52% was achieved with concomitant TON values up to 6.2×102. The attained yield in the presence of [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR_NaOH is considerably higher than the achieved (38%) by the above hybrid C-scorpionate catalyst [FeCl2{κ3-HC(pz)3}]@MOR-D [100]. Moreover, [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]@MOR_NaOH was easily recovered and reused in up to four consecutive cycles, where the first decrease (18%) in the oxidation yield is observed but without significant leaching of [VO2{κ3-HB(3,5-Me2pz)3}]. The authors assign the catalytic activity decrease to some adsorption phenomena that may cause diffusional constraints and restrict the access the complex immobilized at the mesoporosity of the zeolitic material.

The results obtained in the above independent studies [100,103] show that the careful choice of the basic agents used during the treatments assisted by CTAB surfactant play a key role on the effective anchorage of the metal complex and, consequently, on the number of catalytic cycles that can be effectively performed by the supported catalyst.

Mesoporous silicas are of great interest as catalyst supports due to their large surface area and uniform mesopore size distribution which facilitates the anchorage of voluminous species and accelerates mass transfer. Moreover, as it was already mentioned, the abundance of Si-OH groups on the surface of some materials surface makes them excellent materials for surface modification. An illustrative example of the role of mesoporous silicas as supports for metal complexes is provided by Pinto et al. [135]. The application of ordered mesoporous silica SBA-15 and its derived chloropropyl-functionalized silica SBA-15Cl as supports for anchorage of different neutral and charged manganese porphyrins was investigated (see Figure 13). Here, 0.3% w/w complex loadings were obtained for the hybrid materials evaluated as catalysts for cyclohexane oxidation using iodosylbenzene (PhIO) as oxidant. The performance of the SBA-15Cl/MnT-X-PyPCl (X = 2, 3, 4) catalysts was as good as the observed for homogeneous systems, pointing out that catalyst deactivation did not occur upon the anchorage process. However, a change in selectivity (relative to the homogeneous reaction) was observed, as an increase of ca. 10% of cyclohexanol yield was reported by the heterogenization of the catalyst. These results indicate an effective participation of the inorganic matrix, even though, the authors state some difficulty in rationalizing the influence of the support. Nevertheless, as SBA-15Cl exhibits a lipophilic character (due to the hydrophobic nature of the pendant carbon chain), cyclohexane approach should be favored, whereas the one of cyclohexanol product (more polar) may be prevented, thus justifying the increase in the alcohol production and the decrease in cyclohexanone yield, when compared with the homogeneous system. The strong interaction between the manganese porphyrin complexes and the mesoporous silica systems (SBA-15 and SBA-15Cl) was confirmed by their low leaching from the supports even after extensive washings. Moreover, the heterogenized catalysts exhibited high resistance against oxidative decomposition as no considerable changes in their efficiency was detected by reuse in consecutive catalytic cycles.

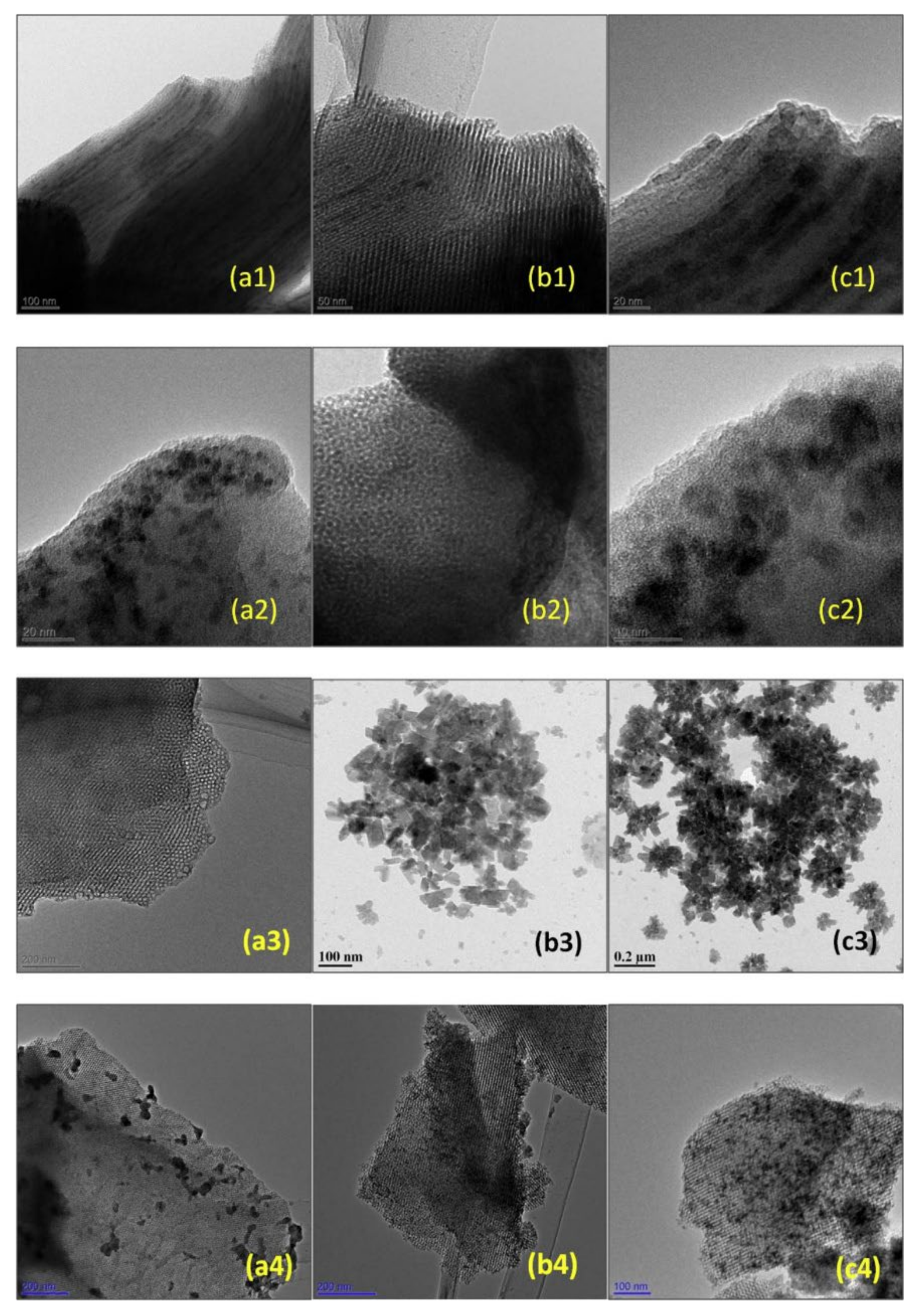

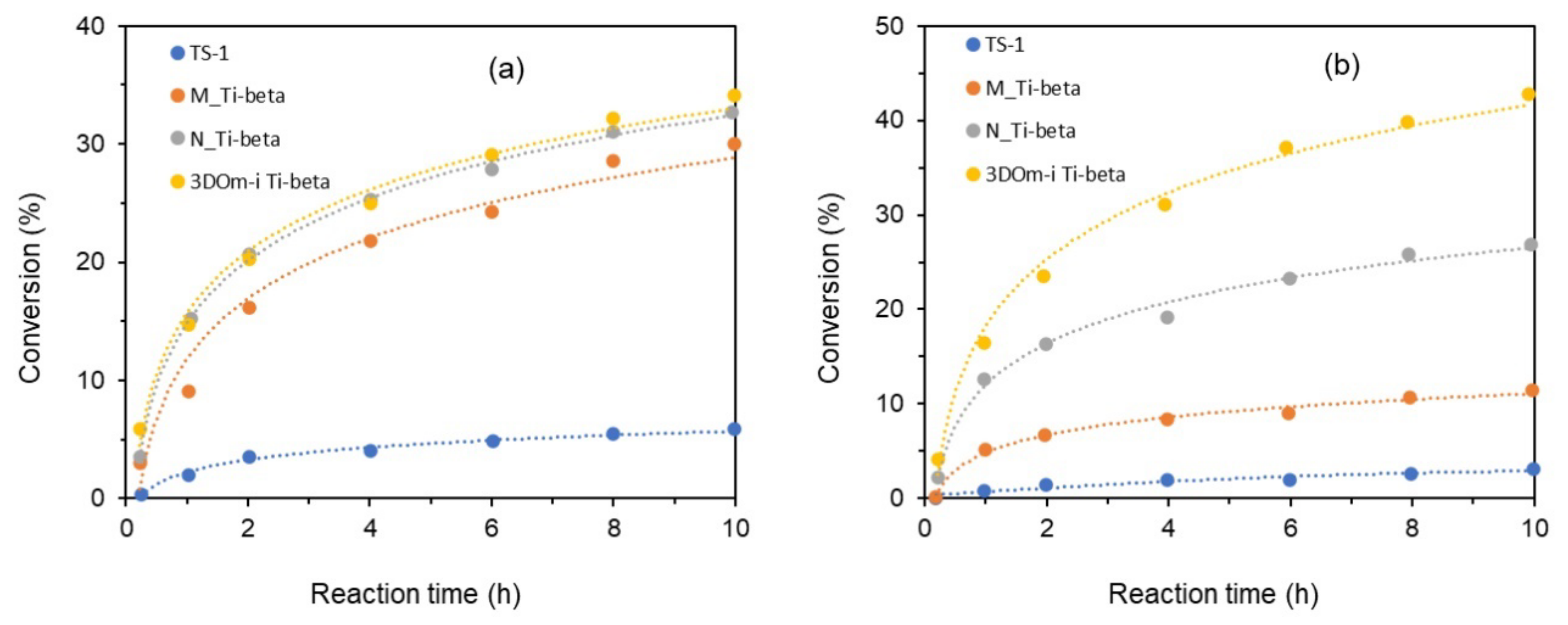

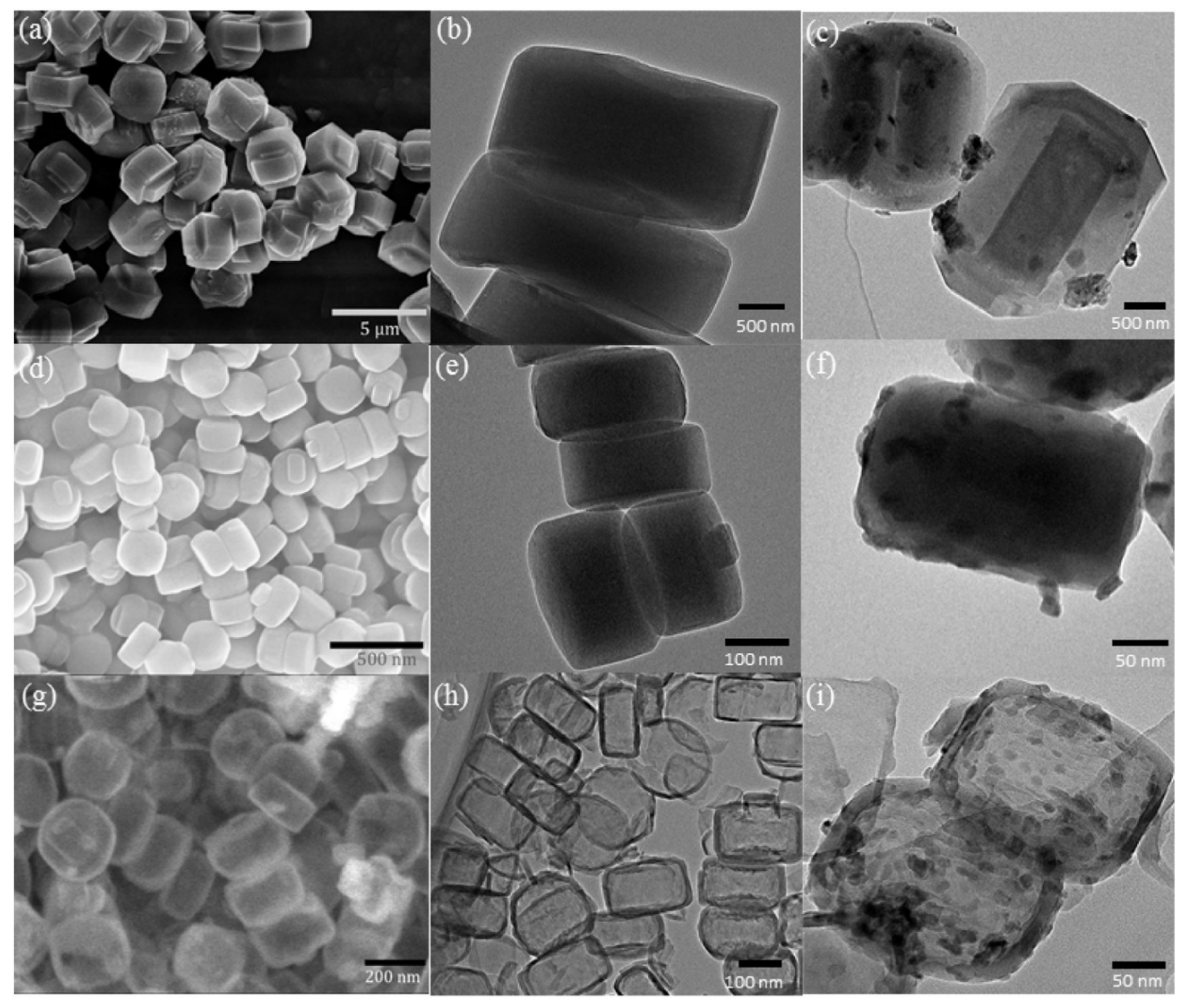

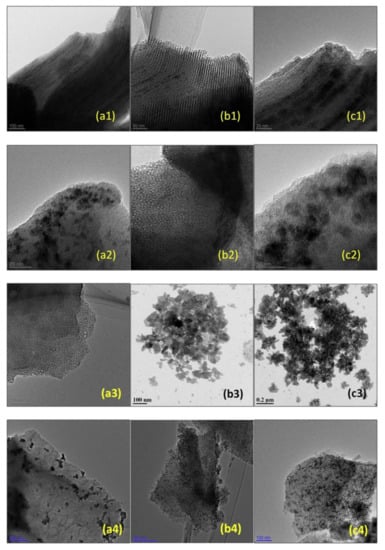

Mesoporous silicas can also be used as effective supports for metal oxide catalysts. The potentialities of several materials were studied. For example, Unnarkat et al. [157] compared the performance of three mesoporous silicas as supports–SBA-15, KIT-6, and FDU-12 for immobilizing the cobalt-molybdenum oxide CoMoO4 and their use in the liquid phase oxidation of cyclohexane by molecular oxygen. The catalysts were characterized by several techniques, including TEM, where the good dispersion of the active species (not uniform) in the mesopores of the support is clearly observed, as well as the typical channel structure of SBA-15, the cubical pore structure for KIT-6, and the hexagonal pore structure for FDU-12 (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

TEM images (a1,b1,c1) 20%CoMo/SBA-15; (a2,b2,c2) 20%CoMo/KIT-6; (a3) FDU-12; (b3,c3) 20%CoMo/FDU-12; (a4) 5%CoMo/KIT-6; (b4) 10%CoMo/KIT-6; (c4) 20%CoMo/KIT-6. Reproduction with permission from Reference [157]. Copyright (2017) Elsevier B.V.

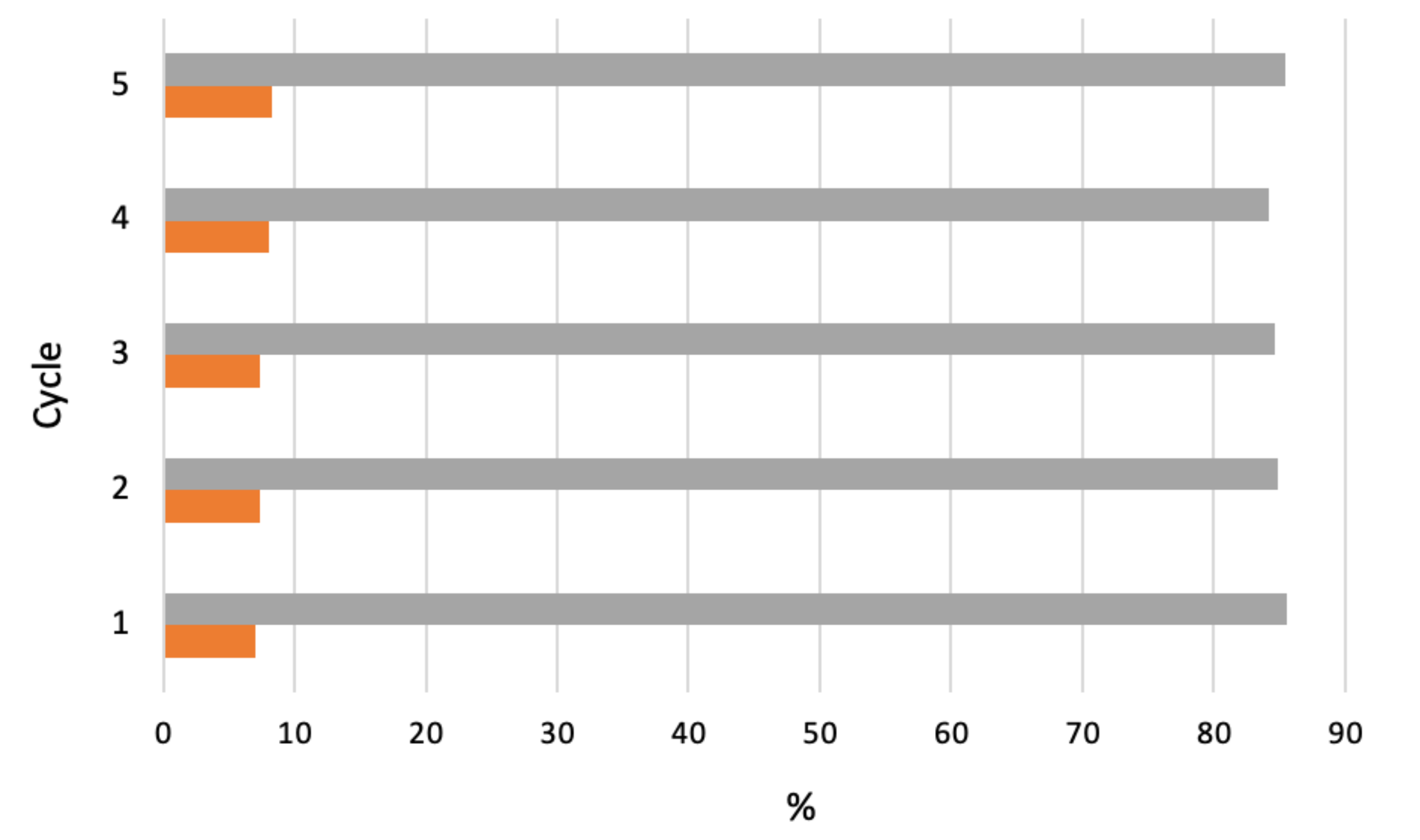

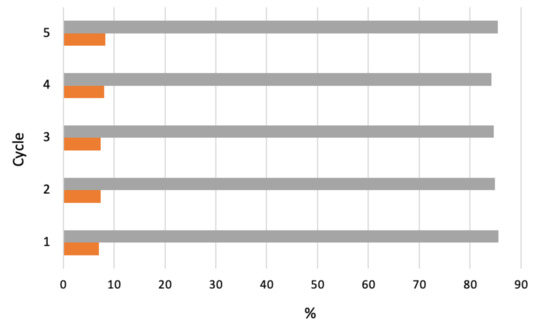

The catalyst performance as function of catalyst loading, pore size, or calcination temperature was studied for each support at 150 °C, 1.0 MPa O2 pressure and 800 rpm stirring. Among the supported catalysts, 20%CoMo/FDU-12 showed the highest activity (up to 8% conversion) for a selectivity of 85% for the cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol mixture. The silica-supported oxide exhibited deactivation, apparently due to adsorption of reaction products. However, a deactivated catalyst could be successfully regenerated by recalcination, which prompted its reuse in a further (up to four) cycle, retaining activity and selectivity over consecutive cycles (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Effect of four cycles of recalcination–reuse of 20%CoMo/FDU-12 catalyst on cyclohexane conversion (■) and selectivity (■) to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone [157].

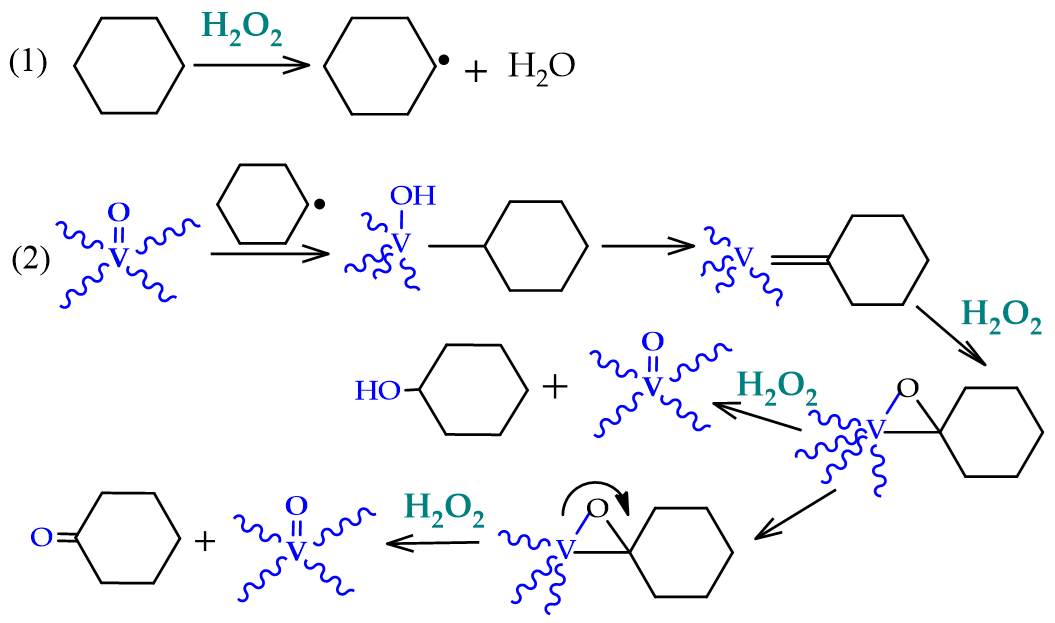

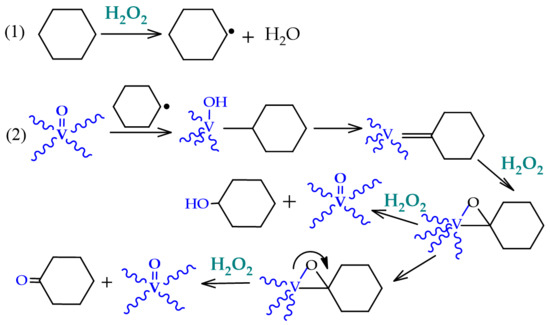

Mesoporous silica KIT-6 presents a unique structure with 3D interpenetrating bicontinuous networks of channels, offering a huge number of active sites as well as high resistance to form clusters, thus attracting a significant interest to act as catalyst support. Rezaei et al. [156] immobilized vanadium phosphate (mainly VOHPO40·5H2O phases) at KIT-6 [(VO)2P2O7 phase after calcination] and applied it for the oxidation of cyclohexane by hydrogen peroxide. The characterization of the supported catalysts by N2 adsorption isotherms revealed a considerable decrease in the surface area and pore volume upon vanadium phosphate loading, suggesting their location inside KIT-6 pores, which agrees with the observed increase in pores diameter.

The authors report a cyclohexane conversion and selectivity toward cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone of 19.3% and 69.9%, respectively, after 4 h reaction with 1:4 cyclohexane: H2O2 molar ratio at 65°C and using 27 wt.% catalyst vanadium loading. The corresponding proposed reaction mechanism is depicted in Figure 18. No significant change in activity or selectivity was found in the first three consecutive catalytic cycles. Then, a lower conversion of cyclohexane (without selectivity loss) was detected. The stability of the VPK-6 immobilized catalyst appears to be due to the high dispersion of vanadium phosphate in the support, as shown by SEM. Moreover, the nature of the textural characteristics for the catalyst after being reused five times remains unchanged, although the surface area and pore volume values present a decrease, most likely due to some blockage of the support pores.

Figure 18.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the oxidation of cyclohexane catalyzed by vanadium phosphate immobilized at KIT-6. Reproduction with permission from Reference [156]. Copyright (2017) Elsevier B.V.

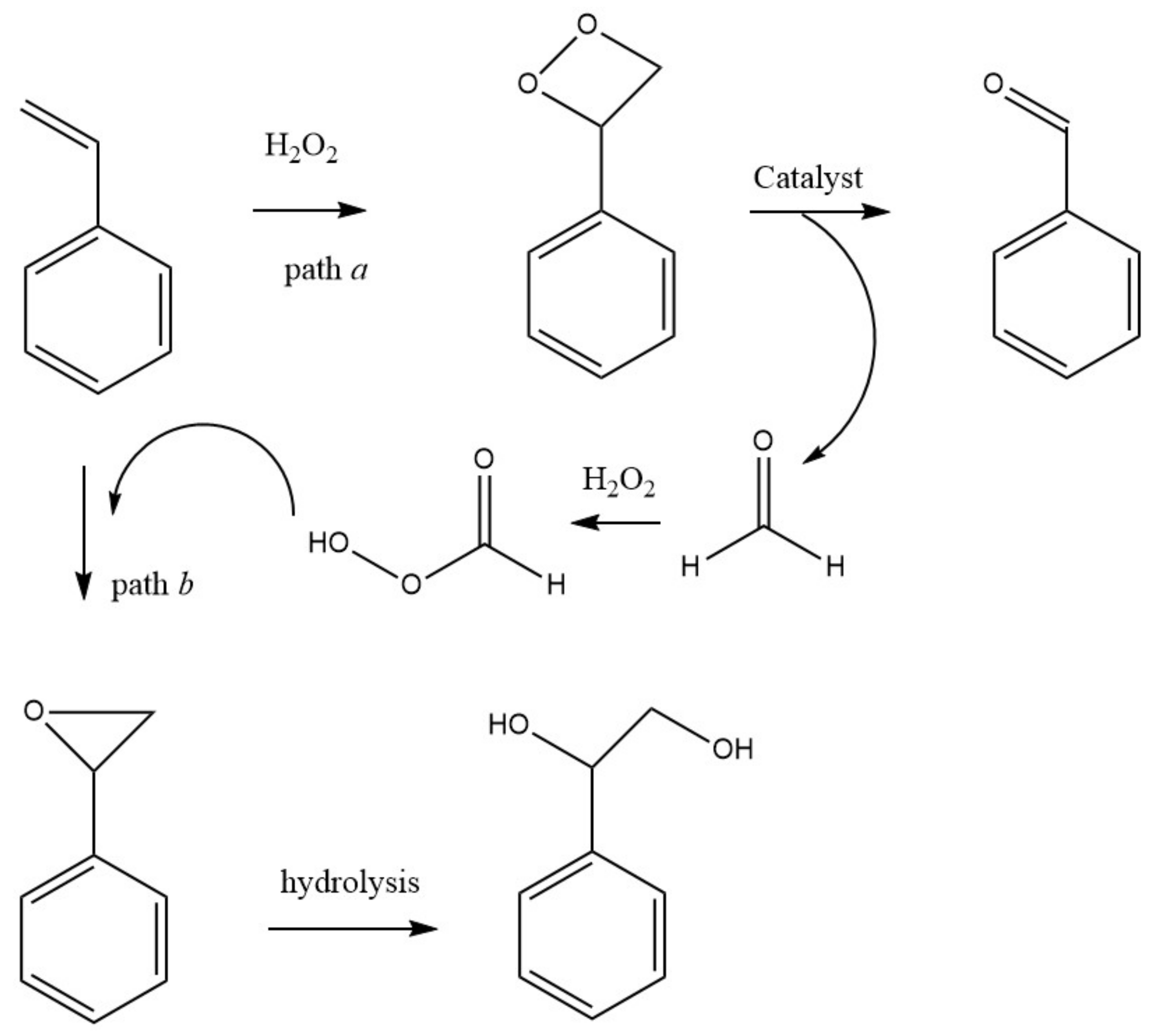

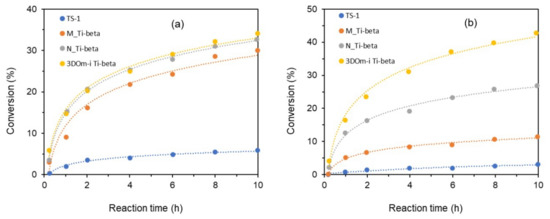

5.2. Oxidation of Alkenes

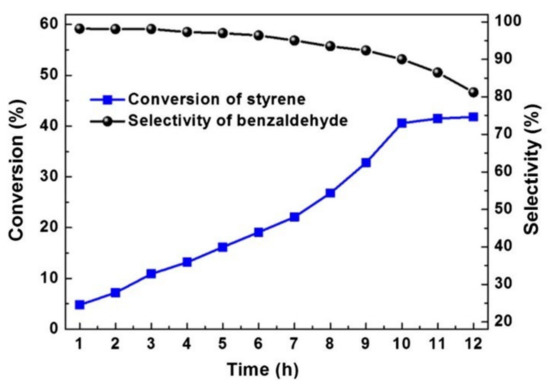

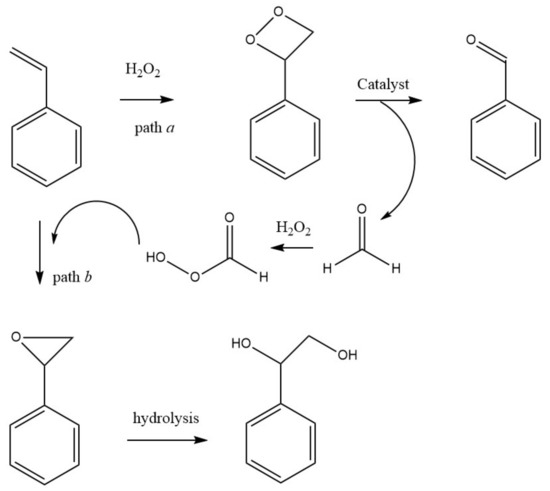

Alkenes are more reactive molecules than alkanes. Therefore, their range of oxidation reactions is also wider. Representative examples of reactions that occur in the presence of metal or metal complexes supported on zeolites and related materials are presented in Table 4. Selected examples are discussed in more detail ahead. It is worth mentioning that styrene oxidation is also considered in this topic because the transformation occurs in the double bond of the vinyl group.

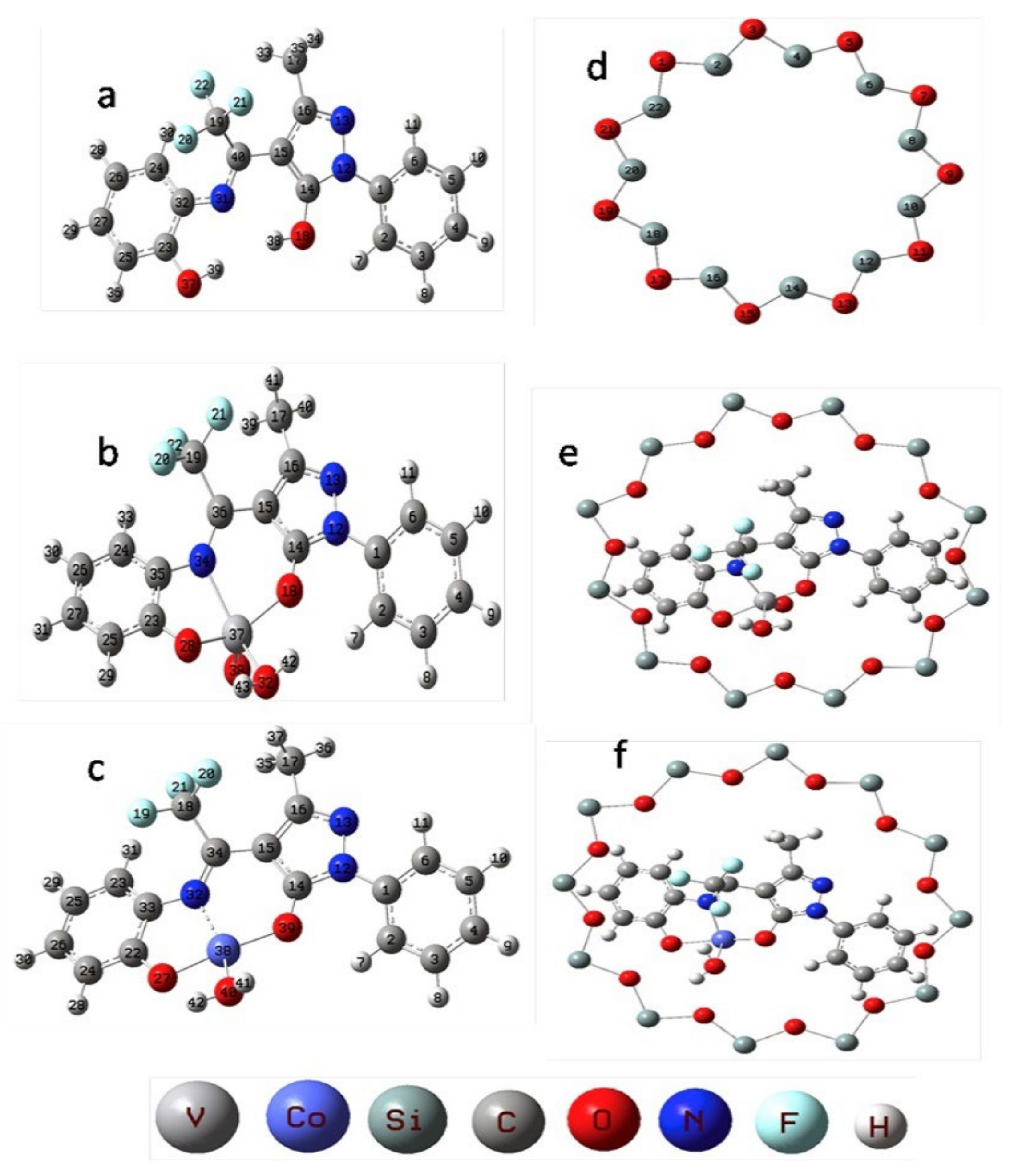

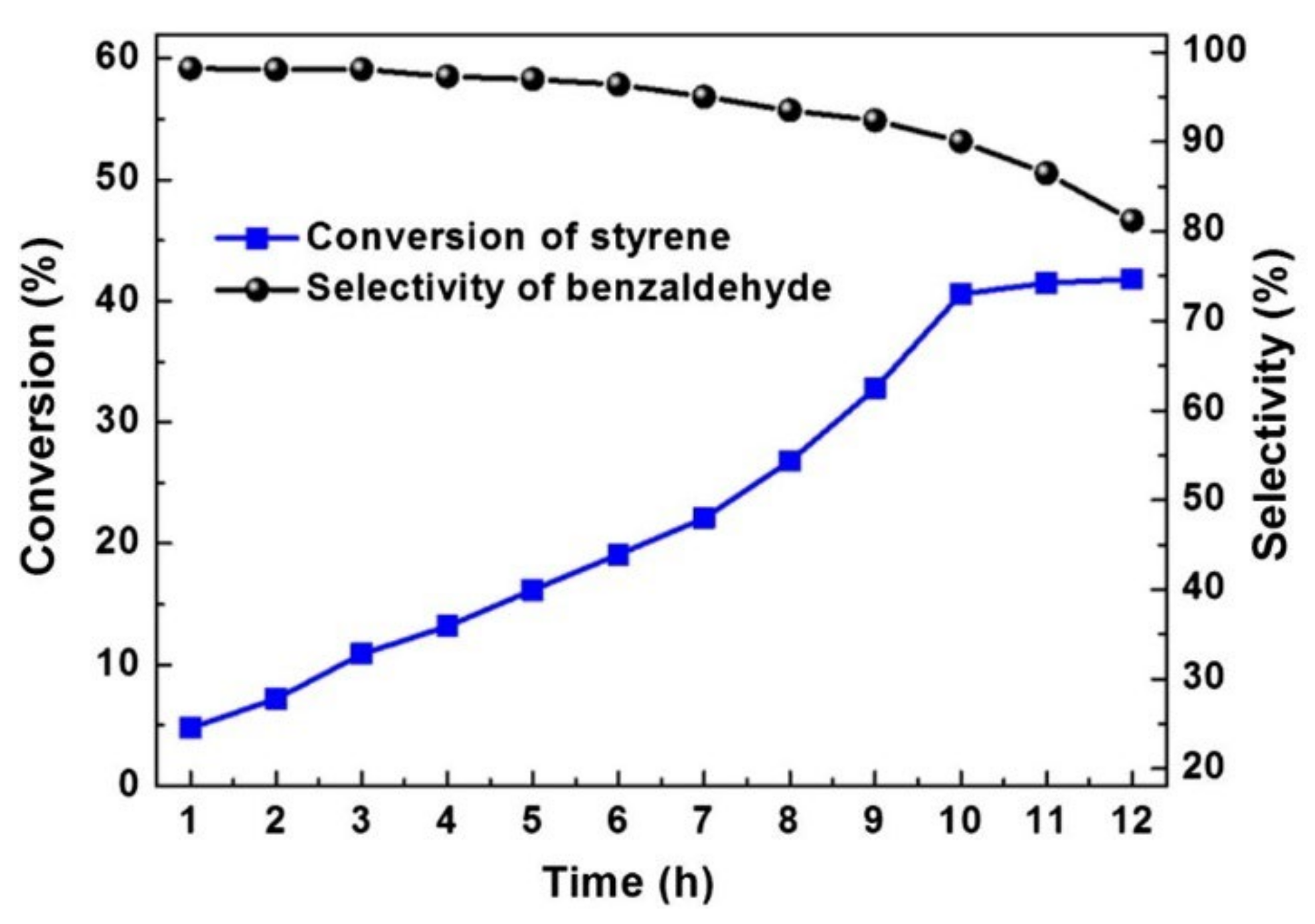

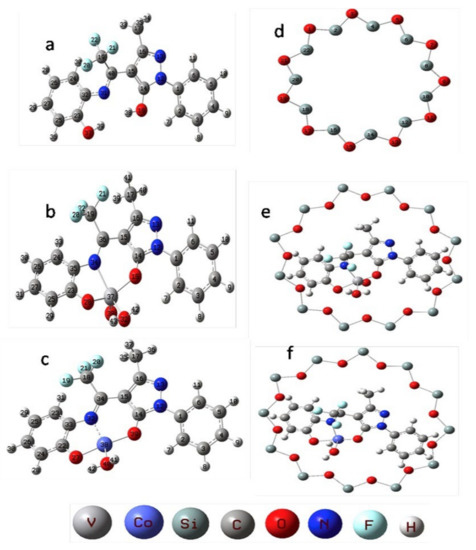

Following the same trend as for reactions involving alkanes, the most used native microporous zeolite as catalytic support is FAU structure (see Table 4), taking advantage of the presence of the supercages that can effectively anchor voluminous catalysts through the flexible ligand method. For example, Modi and co-workers [162] applied Y zeolite entrapped VO2+ or Co(II) pyrazalone complexes bearing the Schiff base ligand L, [VO(L)∙H2O] and Co(L)∙H2O]·H2O (H2L = (Z)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-(2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)imino)ethyl)-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) (Figure 19 a-c) as catalysts for the oxidation of styrene by H2O2. The metal complexes were entrapped in the supercages of the Y zeolite by the flexible ligand procedure, leading to [VO(L)∙H2O]-Y and [Co(L)∙H2O]-Y materials (Figure 19 e-f). The catalytic ability of the hybrid materials [VO(L)∙H2O]-Y and [Co(L)∙H2O]-Y was evaluated under the effect of different experimental variables (amount of catalyst, substrate and oxidant mole ratios, solvents, and reaction time) and compared with the homogeneous systems. [VO(L)·H2O]-Y was found to be the best catalyst, achieving 82% conversion of styrene and high benzaldehyde selectivity (54.9%) along with expected minor amounts of styrene glycol, styrene oxide, and phenyl acetic acid (35.9, 6.7 and 2.4%, respectively). The superior catalytic activity of [VO(L)·H2O]-Y was studied by DFT, highlighting that vanadium-based complex is molecularly more stable and chemically more reactive, led to higher catalytic activity compared to the cobalt analogous. Moreover, [VO(L)·H2O]-Y was recyclable five times with no significant loss of activity.

Figure 19.

Structures for (a) Schiff base H2L; (b) [VO(L)∙H2O]; (c) [Co(L)∙H2O]·H2O; (d) Y zeolite pore opening; (e) [VO(L)∙H2O]-Y and (f) [Co(L)∙H2O]-Y. Reproduction with permission from Reference [162]. Copyright (2017) Elsevier B.V.

Following the same strategy for the immobilization of the active species at the microporous Y zeolite support, Godhani et al. [17], besides testing the catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane (Table 3), also performed the oxidation of cyclohexene by H2O2, in acetonitrile at 80 °C for 18 h) using the prepared catalysts [M(L)]-Y (M = Co(II) or Cu(II); L = Schiff bases). The immobilized metal complexes (within the Y zeolite nanovoids) extensively catalyzed the cyclohexene oxidation to 2-cyclohexen-1-one and 2-cyclohexen-1-ol and were easily recovered and reused without loss of activity and the selectivity for the allylic products. Moreover, the heterogenized catalysts were found highly selective for oxidation of benzene, styrene, limonene, and α-pinene with a moderate conversion.