Abstract

Levansucrases are key enzymes responsible for the synthesis of β-2,6-linked fructans, found in plants and microbes, especially in bacteria. Levansucrases have been applied in the production of levan biopolymer and fructooligosaccharides (FOSs) using sucrose as a substrate as well as in reducing sugar levels in fruit juice. As a result, levansucrases that are active at low temperatures are required for industrial applications to maintain product stability. Therefore, this work firstly reports the novel cold-active levansucrase (SacBPk) isolated from a sucrolytic bacterial strain, P. koreensis HL12. The SacBPk was classified into glycoside hydrolase family 68 subfamily 1 (GH68_1) and comprised a single catalytic domain with the Asp104/Asp267/Glu362 catalytic triad. Interestingly, the recombinant SacBPk demonstrated cold-active levansucrase activity at low temperatures (on ice and 4–40 °C) with the highest specific activity (167.46 U/mg protein) observed at 35 and 40 °C in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0. SacBPk mainly synthesized levan polymer as the major product (129 g/L, corresponding to 25.8% of total sugar) with a low number of short-chain FOSs (GF2–4) (12.8 g/L, equivalent to 2.5% of total sugar) from 500 g/L sucrose after incubating at 35 °C for 48 h. These results demonstrate the industrial application potential of SacBPk levansucrase for levan and FOSs production.

1. Introduction

Fructooligosaccharides (FOSs) are short-chain oligomers of D-fructofuranosyl residues linked by β-(2,6)-linkages, comprising 2–10 fructose units (DP 2–10). FOSs represent non-digestible oligosaccharides with prebiotic properties that promote the growth of beneficial gut microbes [1,2,3]. In contrast, levan is a homopolysaccharide composed of D-fructofuranosyl residues linked by β-(2,6)-linkages with varying degrees of β-(2,1)-branching depending on the origin. Levan-type fructans are primarily synthesized by bacterial enzymes, while linear levan is also produced by some plant species, for example timothy grass (Phleum pratense) and orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata). In addition to its prebiotic potential [4,5], levan is a thermally stable biopolymer (>300 °C) with film-forming and emulsifying capabilities, as well as water- and oil-holding capacity, demonstrating its industrial application in food products, food packaging, and next-generation polymer technology [6,7,8,9,10]. Importantly, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of levan have also been previously reported [11].

FOSs and levan are enzymatically synthesized from sucrose, which is a building block made of levansucrase enzymes found in plants and microbial species. Levansucrases (EC 2.4.1.10) are fructosyltransferases (FTFs) that catalyze the cleavage of glycosidic linkages in sucrose, forming a covalent fructosyl–enzyme complex and releasing glucose. The fructosyl molecule is subsequently transferred to the acceptor molecule by connecting them with β-2,6 glycosidic linkages through transfructosylation reaction, resulting in the synthesis of short-chain oligomers of fructooligosaccharides (FOSs) and long-chain levan biopolymer [12,13,14]. Levansucrases have been generally classified into glycoside hydrolase family 68 (GH68) together with inulosucrases (EC 2.4.1.9) that synthesize inulin-type fructans, which is a linear fructosyl polymer linked with β-2,1 glycosidic linkage. According to the carbohydrate active enzyme classification in the CAZy database (www.cazy.org) updated on 17 December 2024, the members in glycoside hydrolase family 68 (GH68) were divided into two subfamilies: subfamily 1 and 2 [15,16]. The members of the GH68_1 subfamily include levansucrases from genera such as Bacilli, Geobacillus, Priestia, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus. Examples of these are Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus licheniformis BK1, Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168, Geobacillus stearothermophilus ATCC 12980, Lactobacillus gasseri DSM 20077, Priestia megaterium DSM 319, and Streptococcus mutans GS5, which are closely related to microbial inulosucrases (EC 2.4.1.9). Levansucrases classified into the GH68_2 subfamily are found in Erwinia amylovora EA7/74, Erwinia tasmaniensis Et1/99, Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus PAL3, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato str. DC3000, and Zymomonas mobilis subsp. mobilis ATCC 10988. Levansucrases typically contain a single GH68 catalytic domain that resembles a five-bladed β-propeller structure, enclosing a funnel-like central cavity that is negatively charged at the substrate binding site.

This work is the first to describe the sequence and structural annotation of levansucrase (SacBPk) from P. koreensis HL12, as well as its biochemical properties, providing a better understanding of the function of SacBPk in the levansucrase operon identified in the P. koreensis HL12 genome [17]. The recombinant SacBPk exhibited cold-active levansucrase activity, catalyzing FOSs and levan synthesis at low temperatures (on ice and at 4–40 °C), highlighting its potential for industrial-scale applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. In Silico Sequence and Structural Annotation of SacBPk from P. koreensis HL12

The genome analysis of sucrose-utilizing P. koreensis HL12 strain revealed the identification of levansucrase (sacBPk) and endo-levanase (levBk) encoding genes, which are associated with levan and L-FOSs biosynthesis, within the levansucrase operon [17]. The endo-levanase (LevBk), belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 32 (GH32), comprises two domains: the N-terminal β-propeller substrate-binding pocket with a five-bladed structure and the C-terminal β-sandwich structure [18]. The recombinant LevBk specifically cleaved levan from timothy grass into short-chain L-FOSs with a degree of polymerization (DP) of 2–4. To gain a better understanding of the enzymatic pathway involved in sucrose utilizing in P. koreensis HL12, the structure and function of levansucrase (SacBPk) from P. koreensis HL12 were subsequently analyzed in this study.

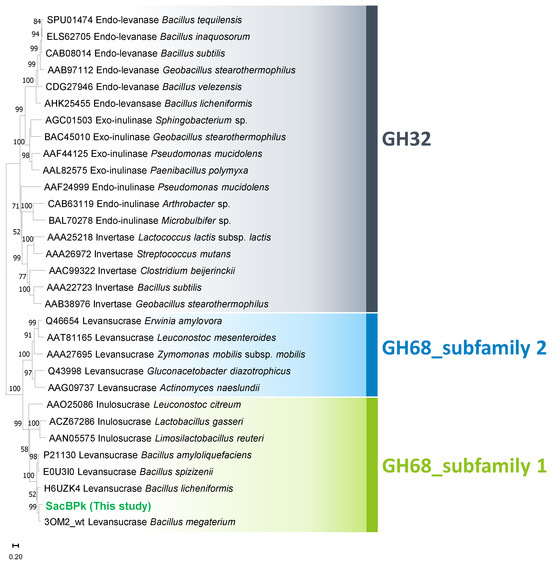

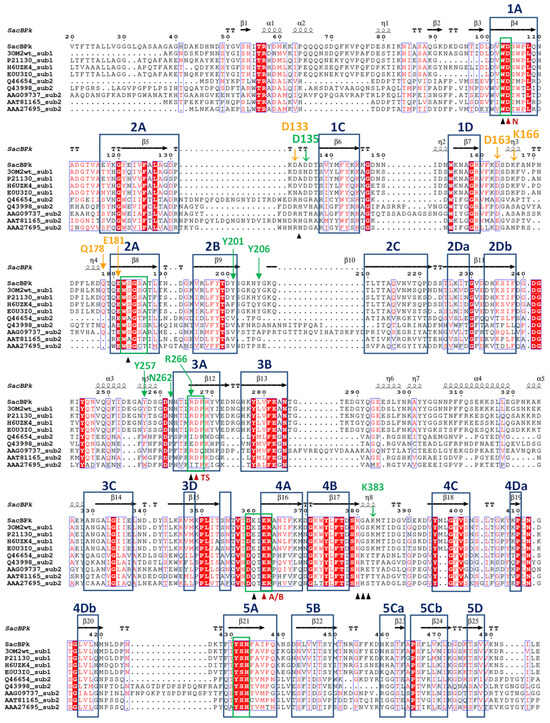

According to sequence annotation, the full sacBPk gene is 1479 bp in length and encodes for 493 amino acids. At the N-terminus, there are 36 amino acids corresponding to the Sec signal peptide (probability 0.96), facilitating the release of SacBPk outside of the cell, which is consistent with findings in other Gram-positive bacteria [14,19]. The catalytic domain of levansucrase is classified into glycoside hydrolase family 68 (GH68) at the C-terminus. SacBPk is closely related to GH68 from P. megaterium (accession number WP_129707399.1) with 82% identity and 91% similarity, which is followed by GH68 from Priestia aryabhattai (accession number WP_048018546.1) with 82% identity and 90% similarity. Evolutionary analysis, compared to the previously biochemically described GH32 and GH68 homologs, classified SacBPk as levansucrase in GH68 subfamily 1, placing it in the same clade as levansucrases from Bacilli (Figure 1). Notably, it is distinctly from subfamily 2 members, which include E. amylovora, G. diazotrophicus, Actinomyces naeslundii, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and Z. mobilis. Furthermore, the GH68 subfamily classification, based on Hornung & Terrapon (2023) [15], along with the amino acid sequence analysis of levansucrase subfamily 1 and 2 (Figure 2), revealed distinct residues in conserved motifs between the two subfamilies. These residues could serve as distinguishing features for classifying the levansucrase GH68 subfamily. The highly conserved sequences in the regions 82IKNIXSA88, 164SDKF167, 211LTTAQVNX218, 329ANGALGIIELN339, and 383KMTIDG388 (numbering for SacBPk) were found exclusively in the SacB GH68 subfamily 1 but were absent in subfamily 2. In contrast, the FRDP region was only found in SacB, which belongs to GH68 subfamily 2 from E. amylovora, G. diazotrophicus, A. naeslundii, L. mesenteroides, and Z. mobilis. This finding suggested that these regions play a role in guiding and differentiating levansucrase subfamilies. A sequence and secondary structural-based comparison of bacterial levansucrases revealed that SacBPk exhibits overall structural similarity to previously characterized levansucrases with conserved motifs (Figure 2). The highly conserved sequence motifs of GH68, which may represent key residues in the central framework of the β-propeller structure of SacBPk, were identified, including motifs 103WD104, 182WSGS185, 266RDP268, 359DEIER363, and 431YSH433, which are homologous residues in SacB from Bacillus megaterium [20].

Figure 1.

Evolutionary analysis of SacBPk levansucrase from P. koreensis HL12 comparing with the 18 homologs of GH32 and 12 homologs of GH68. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 5000 replicates bootstrap test. Bar represents sequence divergence.

Figure 2.

Structural-based sequence alignment of SacBPk levansucrase from P. koreensis HL12 and previously biochemical characterized levansucrases classified as GH68_subfamily 1 and subfamily 2. GH68_subfamily 1 levansucrases are wild-type levansucrases from B. megaterium (3OM2), B. amyloliquefaciens (P21130), B. licheniformis (H6UZK4), and Bacillus spizizenii (E0U3I0). GH68_subfamily 2 levansucrases are levansucrases from E. amylovora (Q46654), G. diazotrophicus (Q43998), A. naeslundii (AAG09737), L. mesenteroides (AAT81165), and Z. mobilis (AAA27695). Highly conserved amino acid residues are shown in the blue box. Secondary structures indicated above are assigned according to the predicted model of SacBPk. The proposed catalytic triad residues Asp104/Asp267/Glu362 are indicated by red triangles, and the neighboring residues are indicated by black triangles. The OB1 and OB2 surface residues were indicated in green and orange color, respectively.

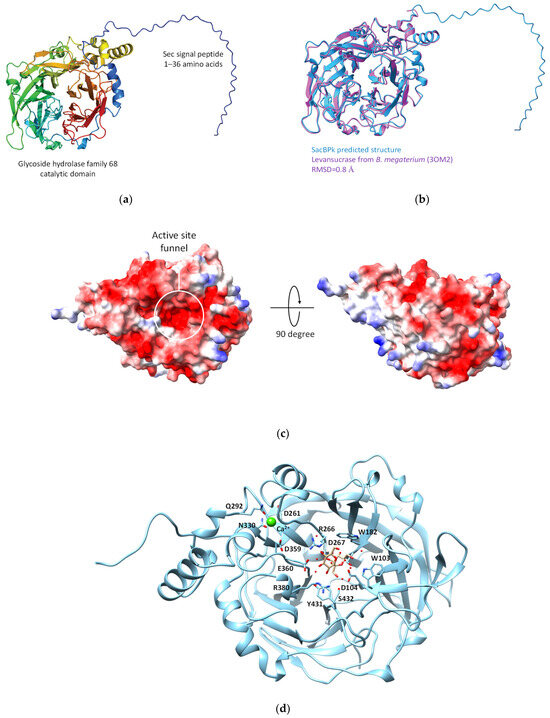

Subsequently, the three-dimensional model of SacBPk was predicted using AlphaFold 2. The structure assessment of the predicted SacBPk model revealed similarity with an RMSD of 0.80 Å [21,22] when compared with the levansucrase from B. megaterium (PDB: 3OM2) [23] (Figure 3a,b). According to the structure annotation, SacBPk features a single domain with a five-bladed β-propeller architecture, where each blade is composed of four antiparallel β-strands adopting the classical “W” topology. The active site is located at the bottom of the central cavity, and a funnel-like opening facilitates access to a deep, negatively charged pocket on the surface. The putative catalytic triad residues Asp104/Asp267/Glu362, located in the central active site, act as the nucleophile, acid–base, and transition-state stabilizer, respectively (Figure 3c,d). These residues are identical to those in other levansucrases, such as those from B. subtilis, Bacillus velezensis, B. megaterium, G. diazotrophicus, E. tasmaniensis, and Brenneria sp. [23,24,25,26,27].

Figure 3.

The predicted three-dimensional model of SacBPk levansucrase from P. koreensis HL12. (a) Cartoon representation Sec signal peptide link with GH68 catalytic domain at the C-terminus. (b) The structure comparison between SacBPk (blue color) and experimental model levansucrase from B. megaterium (3OM2) (purple color). (c) The electrostatic structure represents the cleft of an active site on the protein surface. (d) The proposed key amino acid residues involving in the sucrose binding site of SacBPk.

In addition, the superimposition of SacBPk with the coordinates of SacB from B. subtilis (PDB ID: 6VHQ; D86A/E342A mutant in the presence of levan-type FOSs), which has been shown to clearly identify five substrate-binding subsites via site-directed mutagenesis [26], supports defining the −1, +1, +2, +3, OB1 site surface and the OB2 site of SacBPk. The amino acid residues implicated in substrate-binding subsites, shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, revealed that all SacBPk residues were identical to those in SacB from B. subtilis (SacBBs) with the exception of F182 and N115, which were substituted by Y201 and D133 in SacBPk. F182 (numbering of B. subtilis SacB) interacts with fructosyl 4 through a hydrogen bond and engages in a hydrophobic interaction at the +3 subsite. In SacBBs, substituting F182 with alanine, tryptophan, or tyrosine disrupts acceptor positioning, reducing the catalytic rate and limiting the low molecular weight (LMW) product size to 3.3 kDa. However, F182Y does not affect the Michaelis–Menten constants (Km) or high molecular weight (HMW) levan formation [26].

Table 1.

The proposed key residues for levenhexaose interaction identified in the OB1 site surface of SacBPk from P. koreensis HL12.

In this homologous residue, phenylalanine was identified in B. subtilis and B. licheniformis, which generate products with a degree of polymerization (DP) ranging from 2 to 70 and an average molecular weight (MW) distribution of 6.8 kDa. In contrast, B. megaterium, which contains tyrosine, predominantly produces LMW levans with DPs of 2 to 20 [23,26]. Interestingly, Y201, a residue identical to F182, was found at the +3 subsite and OB1 site surface of SacBPk from P. koreensis HL12 (Figure 2 and Table 1), corresponding to residues in B. megaterium, B. amyloliquefaciens, and G. stearothermophilus [26]. This location differs significantly between the two GH68 subfamilies: tyrosine or phenylalanine is found in subfamily 1, whereas valine is primarily found in subfamily 2.

Within the OB2 site, five residues—N115, D145, K148, Q159, and E162—which are conserved in enzymes from Gram-positive bacteria particularly within the Bacillaceae family, including SacBBs, stabilize the levanhexaose molecule through the direct interactions of hydrogen bonds facilitated by the side chains of these residues [26]. Notably, the amino acid residues D133, D163, K166, Q178, and E181 found in SacBPk exhibited similarity to those in SacBBs (Figure 2 and Table 1) with the exception of D133 (homologous to N115), which replaces asparagine with aspartate, a critical residue for the formation of a hydrogen bond with fructosyl 1.

2.2. Recombinant SacBPk Production and Biochemical Characterization

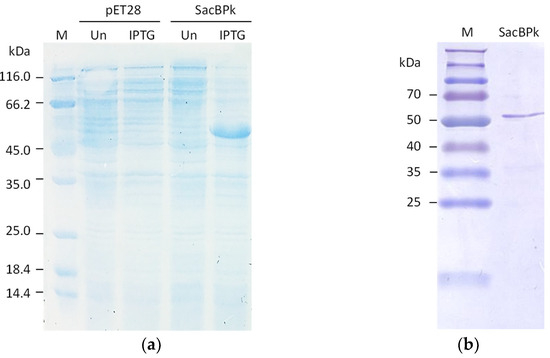

The full-length levansucrase (sacBPk) gene from the P. koreensis was heterologously expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) expression system as a soluble form after induction with 0.25 mM IPTG at 25 °C for 3 h, resulting in the expected molecular weight of 54 kDa (Figure 4a). Regarding protein purification, nearly 90% homogeneity of purified SacBPk was obtained using nickel affinity chromatography (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

The SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant SacBPk. (a) The expression of SacBPk comparing with pET28a(+) empty vector. The cell lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing the empty vector and the recombinant pET28a(+) harboring sacBPk gene was analyzed on a 12% (w/v) acrylamide gel. UN represents an uninduced condition. IPTG indicates induction with 0.25 mM IPTG. (b) Purification of SacBPk using affinity chromatography.

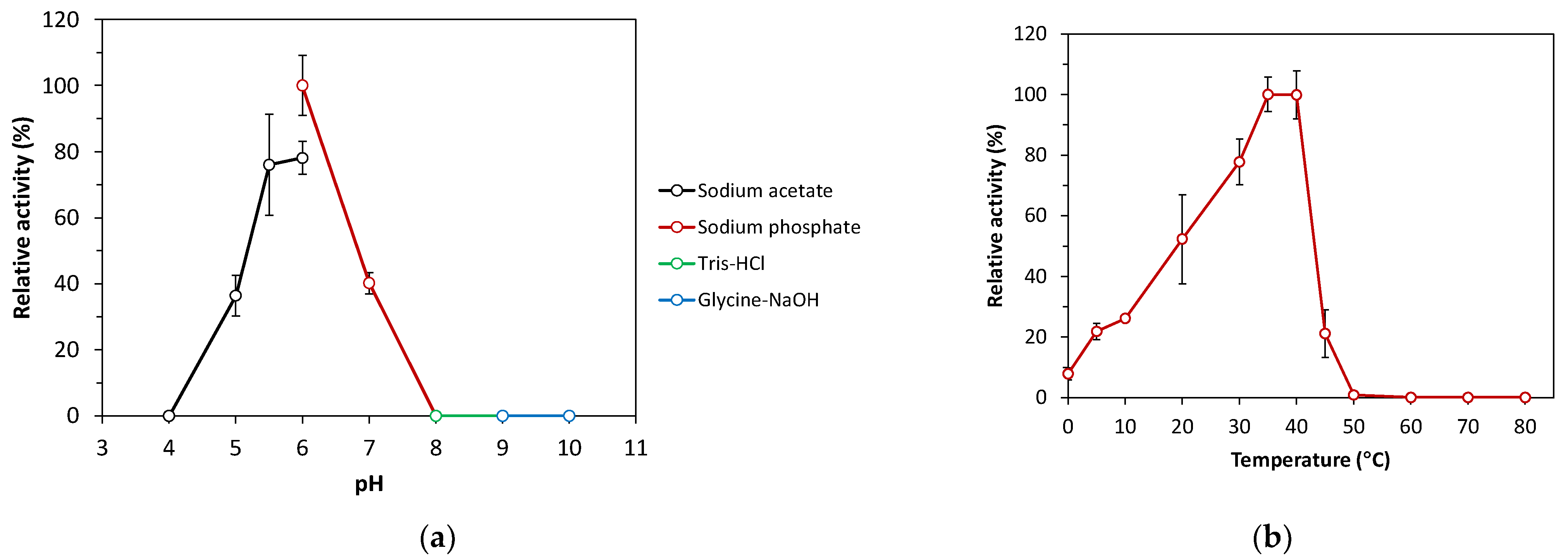

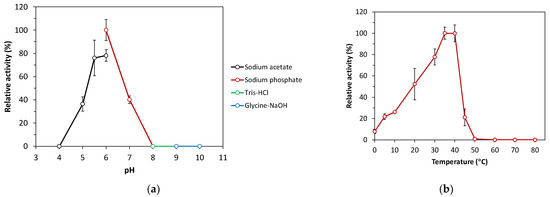

The recombinant SacBPk exhibited enzymatic activity toward sucrose without intrinsic endo-levanase and endo-inulinase activities toward timothy grass levan and chicory inulin, respectively. Based on the hydrolytic activity of levansucrase toward sucrose, SacBPk worked optimally within a broad range, with peak activity at 35 and 40 °C, which was followed by 30 °C (77% residual activity) under optimal pH condition in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 (Figure 5a,b). These findings are consistent with other recombinant microbial levansucrases, which are optimally active between 30 and 60 °C: for example, levansucrases from B. megaterium (37 °C), B. licheniformis 8-37-0-1 (45 °C), and Brenneria goodwinii (40 °C) [28,29]. Remarkably, SacBPk also demonstrated levansucrase activity at low temperature, ranging from 4 to 20 °C (22–52% residual activity) with 8% residual activity in the reaction incubated on ice. In contrast, the activity of sacB from B. velezensis BM-2 and B. subtilis ZW019 dramatically decreased to below 30% relative at 20 °C [27,30,31], while G. stearothermophilus retained 20–30% of its initial activity between 17 and 27 °C [32]. Interestingly, among the SacB discovered in subfamily 1, including those of G. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis, SacBPk from P. koreensis exhibits the highest potential for cold-active levansucrase.

Figure 5.

Effect of pH and temperature on the levansucrase activity of recombinant SacBPk. (a) Optimal pH analysis of SacBPk. The hydrolysis activity was analyzed toward sucrose at 35 °C for 10 min in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.0–6.0, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0–8.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0–9.0, and 50 mM Glycine-NaOH buffer pH 9.0–10.0. (b) The optimal temperature analysis was performed by incubating the reaction on ice (0 °C) and different temperatures (4–80 °C) for 10 min in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0. The experiment has been carried out with six replicates.

Regarding the effect of pH, SacBPk exhibited enzymatic activity in a mild acidic pH range between 5.0 and 6.0 with the highest activity at pH 6.0, which was followed by pH 5.5 (78% residual activity) and 5.0 (36% residual activity). These results correspond with previously reported microbial levansucrases, which are generally active under the acidic conditions below pH 7.0 [33]. However, some levansucrases exhibit a broader pH range; for instance, the levansucrase from Bacillus aryabhattai is most active at pH 8.0, while the levansucrase from Lactobacillus reuteri performs best at pH levels below 5.0 [33]. The highest specific activity of SacBPk was 167.46 U/mg protein in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 at 35 °C. Regarding kinetic characterization, the maximum velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis–Menten coefficient (Km) of the purified SacBPk toward sucrose were 28.54 ± 0.25 µmole/mg/min and 46.15 ± 2.78 mM, respectively. The low Km values indicate a strong enzyme–substrate affinity. When Km values for hydrolysis (KmH) exceed Km values for transfructosylation (KmT), hydrolysis rates are much lower than VmaxH at low substrate concentrations, favoring transfructosylation—unless Vmax for transfructosylation (VmaxT) is much lower than Vmax for hydrolysis (VmaxH). Although Psor-LS is more efficient at hydrolyzing sucrose, its higher KmH compared to Cedi-LS means that at low substrate concentrations, Cedi-LS may show higher hydrolysis rates due to better substrate affinity [34]. The Km values for the hydrolysis and transfructosylation reaction on sucrose are in the range of 7–202 mM in levansucrase, such as B. licheniformis RN-01 LsRN (Km 7.14 mM), B. licheniformis 8-37-0-1WT (Km 33.3 mM), E. tasmaniensis (Km 50.5 mM), B. subtilis (KmH 8.3 mM, KmT 57.6 mM), Pseudomonas orientalis (KmH 117 mM), and Celerinatantimonas diazotrophica (KmH 57 mM, KmT 202 mM) [27,34,35].

2.3. Evaluation of Fructooligosaccharides and Levan Production from Sucrose

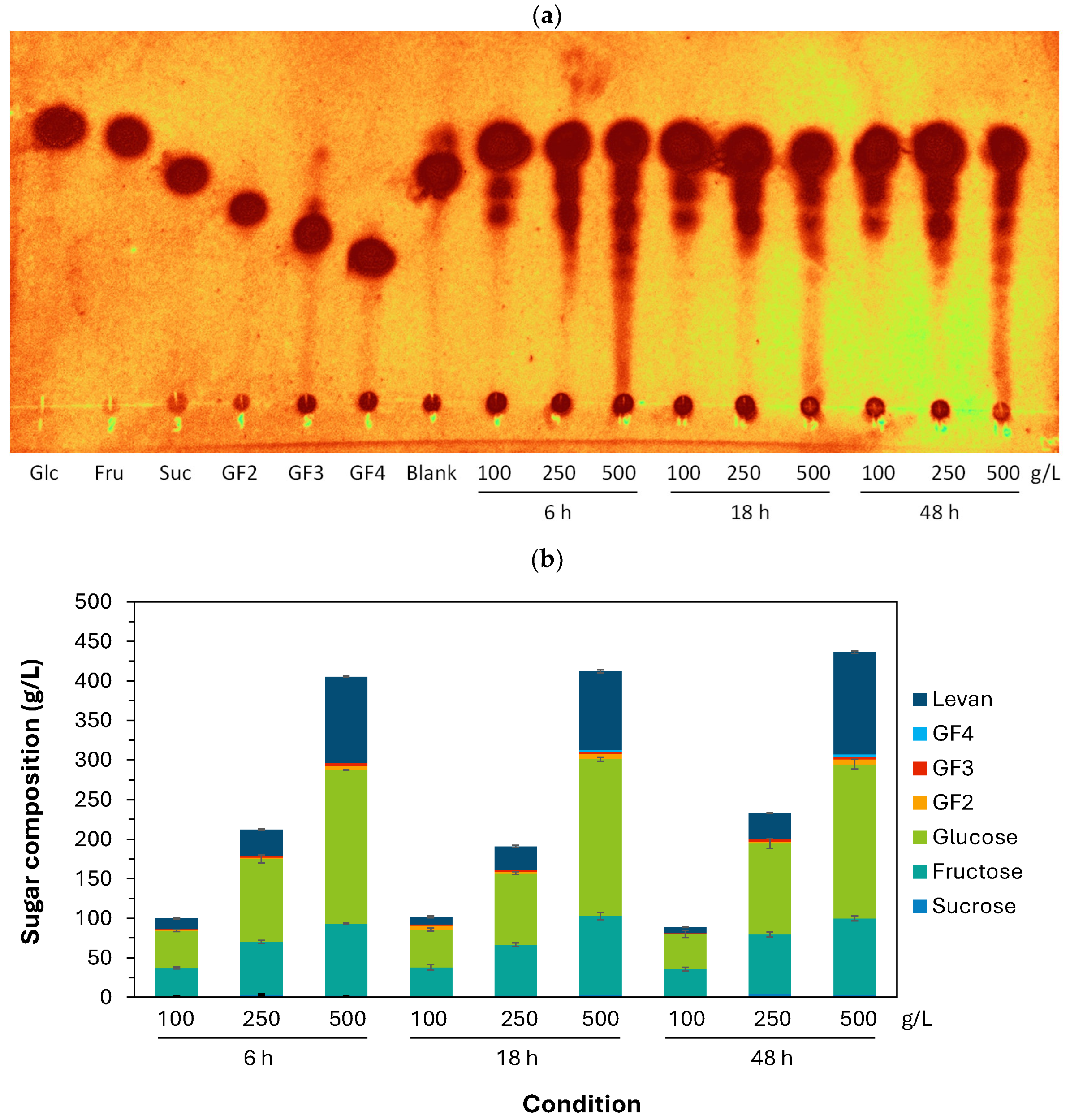

Regarding the functional evaluation of recombinant SacBPk, short-chain FOSs and levan were synthesized from 100, 250, and 500 g/L sucrose after incubation at 35 °C for 6–48 h (Figure 6a,b). The sugar profile analyzed by TLC and HPLC revealed that sucrose at all substrate concentrations (100–500 g/L) was almost completely hydrolyzed within 6 h, releasing short-chain FOSs with varying degrees of polymerization, with GF2–3 as the majority and a minority of GF4 and larger oligomers in the reactions containing 500 g/L after 18 and 48 h. The highest yield of short-chain FOSs was 12.8 g/L, which was composed of GF2 (6.1 g/L), GF3 (3.9 g/L), and GF4 (2.8 g/L), obtained from 500 g/L at 48 h. Interestingly, levan production efficiency gradually increased with sucrose concentration with an average of 10, 31, and 112 g/L of levan synthesized from 100, 250, and 500 g/L initial sucrose concentration, respectively. The highest levan yield (129 g/L equivalent to 28.3% conversion) was obtained from 500 g/L sucrose after incubating at 35 °C for 48 h. Furthermore, SacBPk demonstrated the highest productivity, with 18.22 g levan/h (109 g/L at 6 h) (Table 2), compared to previous reports from B. goodwinii, L. reuteri LTH5448, B. subtilis ZW019, Brenneria sp. EniD312, B. velezensis BM-2, and B. licheniformis 8-37-0-1 [27,31,36,37,38]. This result highlights the exceptional efficiency of SacBPk from P. koreensis for short-term levan production.

Figure 6.

The product profile analysis of FOSs and levan synthesis by recombinant SacBPk from P. koreensis HL12. (a) The qualitative product profile analyzed by TLC method. (b) The sugar profile and content analysis using the HPLC method. The sugar standards are glucose (Glc), fructose (Fru), sucrose (Suc), 1-Kestose (GF2), 1,1-Kestotetraose (GF3), and 1,1,1-Kestopentaose (GF4).

Table 2.

Comparison of levan synthesis using recombinant bacterial levansucrases.

However, all experimental conditions resulted in high levels of glucose and fructose with 44.4–47.8 g/L of glucose and 34.7–36.0 g/L of fructose released from 100 g/L, which was followed by 250 g/L (glucose 90.7–115.0 g/L, fructose 64.0–75.2 g/L) and 500 g/L (glucose 194.2–198.0 g/L, fructose 90.9–99.7 g/L). Regarding the product profile, SacBPk predominantly synthesized levan polymer (129 g/L, corresponding to 25.8% of total sugar) with a low quantity of FOSs (12.8 g/L, equivalent to 2.5% of total sugar), demonstrating the enzymatic specificity of SacBPk, which favored the elongation reaction over short-chain FOSs (GF2-4) synthesis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals, Bacterial Strains, and Plasmids

The expression vector pET28a (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for recombinant enzyme expression under the control of a T7 promoter. The DNA cloning host strain was E. coli DH5a, and recombinant protein expression was carried out using E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). Megazyme supplied the substrates and chemical standards for analysis (timothy grass levan, chicory inulin, 1-Kestose (GF2), 1,1-Kestotetraose (GF3), and 1,1,1-Kestopentaose (GF4) (Wicklow, Ireland).

3.2. Sequence and Structure Annotation

The 493 amino acids of full-length SacBPk from P. koreensis HL12 were analyzed by comparing them to amino acid sequences in the NCBI database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). The signal peptide was predicted using SignalP 6.0 [39], and conserved domain annotation was performed against the Conserved Domains Database (CDD) [40]. Sequence alignment was carried out using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw; accessed on 22 January 2025) [41]. The evolutionary relationship of SacBPk, compared with 18 homologs of GH32 and 12 homologs of GH68, was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with a 5000 replicates bootstrap test in MEGA 11 software [42]. Structural-based sequence alignment between SacBPk in comparison with GH68_subfamily 1 and subfamily 2 was subsequently analyzed using ESPript 3 [43]. To elucidate the three-dimensional structure of SacBPk, the prediction through homology modeling based on multiple sequence alignment with no gap was carried out using AlphaFold in the ChimeraX 1.9 [44,45,46], which was followed by the quantitative evaluation of the predicted structure by superimposition with the X-crystallography structure of levansucrase (SacB) from B. megaterium (PDB 3OM2) using Matchmaker in ChimeraX 1.9 [47]. The VADAR and MolProbity were used to evaluate the stereochemical quality and structural geometry of the SacBPk predicted model [48,49]. Protein structure analysis and visualization were conducted using Chimera 1.17.3 [50].

3.3. Identification of Levansucrase (sacBPk) Gene from P. koreensis HL12

The genomic DNA of P. koreensis HL12 was extracted using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The full-length levansucrase gene (sacBPk) was amplified from genomic DNA of P. korensis HL12 using SacBPk/F (5′-ATGAAAGCAAACTCAACGAAAGCA-3′) and SacBPk/R (5′-CTTATCTTCCGTTA ACTGACCTTG-3′) primers designed based on the levansucrase gene (contig no. 4022) found in the P. koreensis HL12 genome [17] using the Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the following step: pre-denaturation (95 °C for 5 min), followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 30 s), and extension (72 °C for 2 min), and a final extension step (72 °C for 10 min). The PCR product was purified using a GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and cloned into pJET1.2/blunt vector (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and transformed into the E. coli DH5α cloning host. The sequence of the sacBPk gene was subsequently analyzed by the Sanger sequencing method (Macrogen, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The putative signal peptide and cleavage site in sacBPk gene was predicted using the SignalP 6.0 based on neural network models and deep learning algorithms [39]. The evolutionary tree of SacBPk levansucrase from P. koreensis HL12, comparing with the 18 homologs of GH32 and 12 homologs of GH68, was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with a 5000 replicate bootstrap test using MEGA 11 software [42]. An amino acid sequence alignment was performed by the ClustalW program [41].

3.4. Recombinant Plasmid Construction and Protein Production

For recombinant plasmid construction, a full-length sacBPk gene was amplified using primers SacBPk/NdeI/F (5′-GCCATATGAAAGCAAACTCAACGAAAGCA-3′) and SacBPk/XhoI/R (5′-GCCTCGAGCTTATCTTCCGTTAACTGACCTTG-3′) incorporated with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, respectively. The sacBPk gene fragment was cloned into pET28a plasmid and subsequently transformed into E. coli DH5α and selected on LB agar supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. After the sequence verification, the pET28sacBPk plasmid was transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) expression host for protein production. The transformants were selected and validated by colony PCR with gene-specific primers.

The SacBPk was produced by culturing 1% (v/v) of overnight inoculum in 800 mL LB broth containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C, 200 rpm until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.5 to 0.8. The expression was induced by adding 0.25 mM IPTG and further incubated at 25 °C for 3 h. The cell was harvested using centrifugation at 8000× g at 4 °C for 10 min and resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, which was followed by cell disruption by sonication (VCX 750 Ultrasonic Processors, Sonics Ultrasonic Vibra Cell, CT, USA) using an amplitude of 60% with pulse on/off 10 s, 4 min. The soluble protein fraction was then isolated using centrifugation at 12,000× g at 4 °C for 30 min. The purification of SacBPk with 6xHis-tag at the C-terminus was conducted using a HisTrapTM FF affinity column (GE Healthcare, Danderyd, Sweden) that was pre-equilibrated with binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole) and subsequently eluted with the elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 500 mM NaCl and 100 mM imidazole). The protein was then desalted using 10 kDa Macrosep® Centrifugal Filters (Pall, Port Washington, NY, USA). The protein pattern and concentration were analyzed using 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), respectively.

3.5. Enzyme Activity Assay and Biochemical Characteristics Analysis

Levansucrase activity was analyzed based on the amount of liberated glucose from the hydrolysis α-1,2 glycosidic bond of sucrose using the 3,5-dinitrosalisylic acid (DNS) method [51]. One milliliter of reaction mixture contained an appropriate dilution of enzyme in 1% (w/v) of sucrose dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0. The reaction was incubated at 35 °C for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm after heat inactivation at 100 °C for 10 min. One unit of levansucrase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmole of glucose per minute [38,52,53]. To investigate the biochemical characteristics of recombinant SacBPk, the effect of temperature on levansucrase activity was examined over a temperature range of 0 °C (on ice) to 80 °C for 10 min, using 1% (w/v) sucrose dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 as a substrate. The optimal pH of SacBPk was investigated in various pH values ranging from 4.0 to 10.0 in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.0–6.0, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0–8.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0–9.0, and 50 mM glycine-sodium hydroxide pH 9.0–10.0 at 35 °C for 10 min. The experiments were carried out with six replicates. The enzyme kinetic evaluation was performed by incubating 0.4 ug of the enzyme with varying sucrose concentration (1 to 20 mg/mL) dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 at 35 °C for 5–45 min. The Km and Vmax were calculated according to the Michaelis–Menten equation using SigmaPlot 12.0.

3.6. FOSs and Levan Biopolymer Synthesis

The transfructosylation performance of recombinant SacBPk was analyzed using sucrose as a substrate. The reaction contained 5 μg of SacBPk incubated with varying sucrose concentrations of 100, 250, and 500 mg/mL in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 at 35 °C with shaking at 1000 rpm using a Thermomixer C (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 6, 18, and 48 h. The reaction was then inactivated by boiling at 100 °C for 10 min. The sugar profile released from the hydrolysis reaction was analyzed using thin layer chromatography (TLC) at room temperature, using TLC Silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in a mobile phase mixture of n-butanol, acetic acid, and distilled water (5:2:3 ratio). The spot was visualized by developing solution containing 0.1% (w/v) orcinol in a mixture of ethanol and sulfuric acid (95:5 ratio). The color was further developed by heating the TLC plate at 100 °C until the spots appeared, after which the TLC plate was visualized using TLC Explorer (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For the quantification of mono- and oligosaccharides in the reaction, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was conducted. The sample was dissolved in 65% (v/v) acetonitrile, filtered with a 0.2 μm syringe filter, and analyzed using an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with a Shodex Asahipak NH2P-50 4E column (Shodex, Tokyo, Japan) at 40 °C. The system was equipped with a refractive index (RID) detector using 65% (v/v) acetonitrile as the mobile phase with a flow rate 0.7 mL/min. For all analyses, glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), fructose (Sigma-Aldrich), sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich), 1-Kestose (GF2) (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland), 1,1-Kestotetraose (GF3) (Megazyme), and 1,1,1-Kestopentaose (GF4) (Megazyme) were used as standards.

4. Conclusions

Novel cold-active levansucrase (SacBPk) from the P. koreensis HL12 strain was analyzed both structurally and biochemically in this study. The enzyme specifically catalyzed the conversion of sucrose into levan polymer as the major product and short-chain FOSs at a wide range of substrate concentrations (100–500 g/L). It exhibited the highest levan productivity with 18.2 g levan/h at 6 h of reaction time. Our findings suggest that the cold-active activity of SacBPk makes it a promising biocatalyst for low-temperature processing applications, such as in the fruit juice and beverage industry, to reduce sucrose content and increase the production of FOSs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and B.B.; methodology, H.L., N.P., T.K., S.T. and B.B.; software, P.J. and B.B.; validation, H.L. and B.B.; formal analysis, H.L., P.J. and B.B.; investigation, H.L. and B.B.; resources, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and B.B.; writing—review and editing, H.L., N.P., T.K., P.J., S.T. and B.B.; visualization, P.J. and B.B.; supervision, H.L. and B.B.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fundamental Fund fiscal year 2024, Thammasat University.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Enzyme Technology Research Team, National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology and Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Thammasat University. The authors acknowledge support from S.M. Chemical Supplies Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand) for providing TLC Explorer for TLC visualization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- Ahmad, W.; Nasir, A.; Prakash, S.; Hayat, A.; Rehman, M.U.; Khaliq, S.; Akhtar, K.; Anwar, M.A.; Munawar, N. In vitro and in vivo interventions reveal the health benefits of levan-type exopolysaccharide produced by a fish gut isolate Lactobacillus reuteri FW2. Life 2025, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondarenko, O.M.; Ivask, A.; Kahru, A.; Vija, H.; Titma, T.; Visnapuu, M.; Joost, U.; Pudova, K.; Adamberg, S.; Visnapuu, T.; et al. Bacterial polysaccharide levan as stabilizing, non-toxic and functional coating material for microelement-nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Biosynthesis and prebiotic activity of a linear levan from a new Paenibacillus isolate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamberg, K.; Tomson, K.; Talve, T.; Pudova, K.; Puurand, M.; Visnapuu, T.; Alamäe, T.; Adamberg, S. Levan enhances associated growth of Bacteroides, Escherichia, Streptococcus and Faecalibacterium in fecal microbiota. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, A.A.; Elattal, N.A.; Amin, M.A.; Ali, A.E.; Mansour, N.M.; Awad, G.E.A.; Farrag, A.R.H.; Esawy, M.A. In vivo assessment of possible probiotic properties of Bacillus subtilis and prebiotic properties of levan. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummaleti, G.; Sarma, C.; Kalakandan, S.K.; Gazula, H.; Sivanandham, V.; Anandharaj, A. Characterization of levan produced from coconut inflorescence sap using Bacillus subtilis and its application as a sweetener. LWT 2022, 154, 112697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouallegue, A.; Sabbah, M.; Di Pierro, P.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Bourhia, M.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S. Properties of active levan-bitter vetch protein films for potential use in food packaging applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42787–42796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavegowda, N.; Baek, K.-H. Advances in functional biopolymer-based nanocomposites for active food packaging applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.A.; Hassan, R.A.; Abdou, A.M.; Elsaba, Y.M.; Aloufi, A.S.; Sonbol, H.; Korany, S.M. Bio_fabricated levan polymer from Bacillus subtilis MZ292983.1 with antibacterial, antibiofilm, and burn healing properties. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira, E.C.; Rebouças, J.S.; Pinheiro, I.O.; Formiga, F.R. Levan-based nanostructured systems: An overview. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 580, 119242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, R.; Siddartha, G.; Sundhar Reddy, C.H.; Harish, B.S.; Janaki Ramaiah, M.; Uppuluri, K.B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory levan produced from Acetobacter xylinum NCIM2526 and its statistical optimization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 123, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Fleites, C.; Ortiz-Lombardia, M.; Pons, T.; Tarbouriech, N.; Taylor, E.J.; Arrieta, J.G.; Hernandez, L.; Davies, G.J. Crystal structure of levansucrase from the Gram-negative bacterium Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus. Biochem. J. 2005, 390, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Futterer, K. Structural framework of fructosyl transfer in Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2003, 10, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oner, E.T.; Hernandez, L.; Combie, J. Review of levan polysaccharide: From a century of past experiences to future prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornung, B.V.H.; Terrapon, N. An objective criterion to evaluate sequence-similarity networks helps in dividing the protein family sequence space. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1010881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakarn, H.; Prongjit, D.; Mhuantong, W.; Trakarnpaiboon, S.; Bunterngsook, B. Exploring levansucrase operon regulating levan-type fructooligosaccharides (L-FOSs) production in Priestia koreensis HL12. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakarn, H.; Bunterngsook, B.; Jaikaew, P.; Kuantum, T.; Wansuksri, R.; Champreda, V. Functional characterization of recombinant endo-levanase (LevBk) from Bacillus koreensis HL12 on short-chain levan-type fructooligosaccharides production. Protein J. 2022, 41, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchert, T.V.; Nagarajan, V. Structure-function studies on the Bacillus myloliquefaciens levansucrase signal peptide. In Genetics and Biotechnology of Bacilli; Zukowski, M.M., Ganesan, A.T., Hoch, J.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Homann, A.; Biedendieck, R.; Götze, S.; Jahn, D.; Seibel, J. Insights into polymer versus oligosaccharide synthesis: Mutagenesis and mechanistic studies of a novel levansucrase from Bacillus megaterium. Biochem. J. 2007, 407, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R. Methods of protein structure comparison. Methods Mol Biol 2012, 857, 231–257. [Google Scholar]

- Strube, C.P.; Homann, A.; Gamer, M.; Jahn, D.; Seibel, J.; Heinz, D.W. Polysaccharide synthesis of the levansucrase SacB from Bacillus megaterium is controlled by distinct surface motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17593–17600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polsinelli, I.; Caliandro, R.; Demitri, N.; Benini, S. The structure of sucrose-soaked levansucrase crystals from Erwinia tasmaniensis reveals a binding pocket for levanbiose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ni, D.; Hou, X.; Pijning, T.; Guskov, A.; Rao, Y.; Mu, W. Crystal structure of levansucrase from the Gram-negative bacterium Brenneria provides insights into its product size specificity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 5095–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raga-Carbajal, E.; Diaz-Vilchis, A.; Rojas-Trejo, S.P.; Rudino-Pinera, E.; Olvera, C. The molecular basis of the nonprocessive elongation mechanism in levansucrases. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y. Cloning and expression of levansucrase gene of Bacillus velezensis BM-2 and enzymatic synthesis of levan. Processes 2021, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Fu, F.; Zhao, R.; Jin, L.; He, C.; Xu, L.; Xiao, M. A recombinant levansucrase from Bacillus licheniformis 8-37-0-1 catalyzes versatile transfructosylation reactions. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneli, C.; Biedendieck, R.; David, F.; Jahn, D.; Wittmann, C. High yield production of extracellular recombinant levansucrase by Bacillus megaterium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3343–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhao, F.; Yin, N.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y. Biosynthesis and structural characterization of levan by a recombinant levansucrase from Bacillus subtilis ZW019. Waste Biomass Valori. 2022, 13, 4599–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, B.; Mu, W. Efficient biosynthesis of levan from sucrose by a novel levansucrase from Brenneria goodwinii. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthanavong, L.; Tian, F.; Khodadadi, M.; Karboune, S. Properties of Geobacillus stearothermophilus levansucrase as potential biocatalyst for the synthesis of levan and fructooligosaccharides. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013, 29, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Ni, D.; Zhang, W.; Guang, C.; Mu, W. A review of fructosyl-transferases from catalytic characteristics and structural features to reaction mechanisms and product specificity. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guang, C.; Zhang, X.; Ni, D.; Zhang, W.; Xu, W.; Mu, W. Identification of a thermostable levansucrase from Pseudomonas orientalis that allows unique product specificity at different temperatures. Polymers 2023, 15, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Soto, M.E.; Porras-Domínguez, J.R.; Rodríguez-Alegría, M.E.; Morales-Moreno, L.A.; Díaz-Vilchis, A.; Rudiño-Piñera, E.; Beltrán-Hernandez, N.E.; Rivera, H.M.; Seibel, J.; López Munguía, A. Implications of the mutation S164A on Bacillus subtilis levansucrase product specificity and insights into protein interactions acting upon levan synthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, J.; Lu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Xiao, M. Isolation, structural characterization and immunological activity of an exopolysaccharide produced by Bacillus licheniformis 8-37-0-1. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5528–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, D.; Xu, W.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Mu, W. Biosynthesis of levan from sucrose using a thermostable levansucrase from Lactobacillus reuteri LTH5448. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Ni, D.; Yu, S.; Zhang, T.; Mu, W. Insights into hydrolysis versus transfructosylation: Mutagenesis studies of a novel levansucrase from Brenneria sp. EniD312. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gislason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, A.; Mohamedali, A.; Ranganathan, S. Protocol for Protein Structure Modelling. Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology: ABC of Bioinformatics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 252–272. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. A Publ. Protein Soc. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. A Publ. Protein Soc. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Huang, C.C.; Ferrin, T.E. Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF Chimera. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, L.; Ranjan, A.; Zhang, H.; Monzavi, H.; Boyko, R.F.; Sykes, B.D.; Wishart, D.S. VADAR: A web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3316–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.J.; Headd, J.J.; Moriarty, N.W.; Prisant, M.G.; Videau, L.L.; Deis, L.N.; Verma, V.; Keedy, D.A.; Hintze, B.J.; Chen, V.B.; et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. A Publ. Protein Soc. 2018, 27, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 2002, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Qi, X.; Hart, D.J.; Gao, H.; An, Y. Expression and characterization of levansucrase from Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghith, K.S.; Dahech, I.; Belghith, H.; Mejdoub, H. Microbial production of levansucrase for synthesis of fructooligosaccharides and levan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).