Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction for the Preparation of Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Typical Procedure of Organoselenium-Mediated Controlled Radical Polymerization

2.4. Typical Procedure of Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Addition of PS-Se to PEGMA

2.5. Fabrication of PS-Se-b-PEGMA Micelles

2.6. Chemical Oxidation of PS-Se-b-PEGMA Micelles by H2O2

2.7. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Study of the Micelles

2.8. Drug Loading

2.9. Oxidation-Responsive Drug Release

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Organoselenium-Mediated Controlled Radical Polymerization

3.2. Reaction Condition Optimization of Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction

3.3. Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction of PS-Se-1 and PEGMAs with Different Molecular Weights

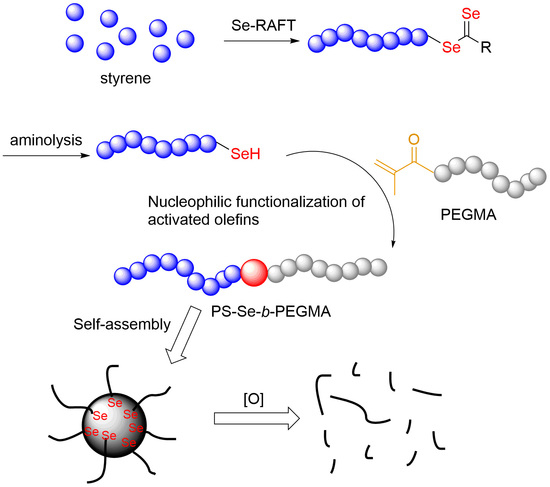

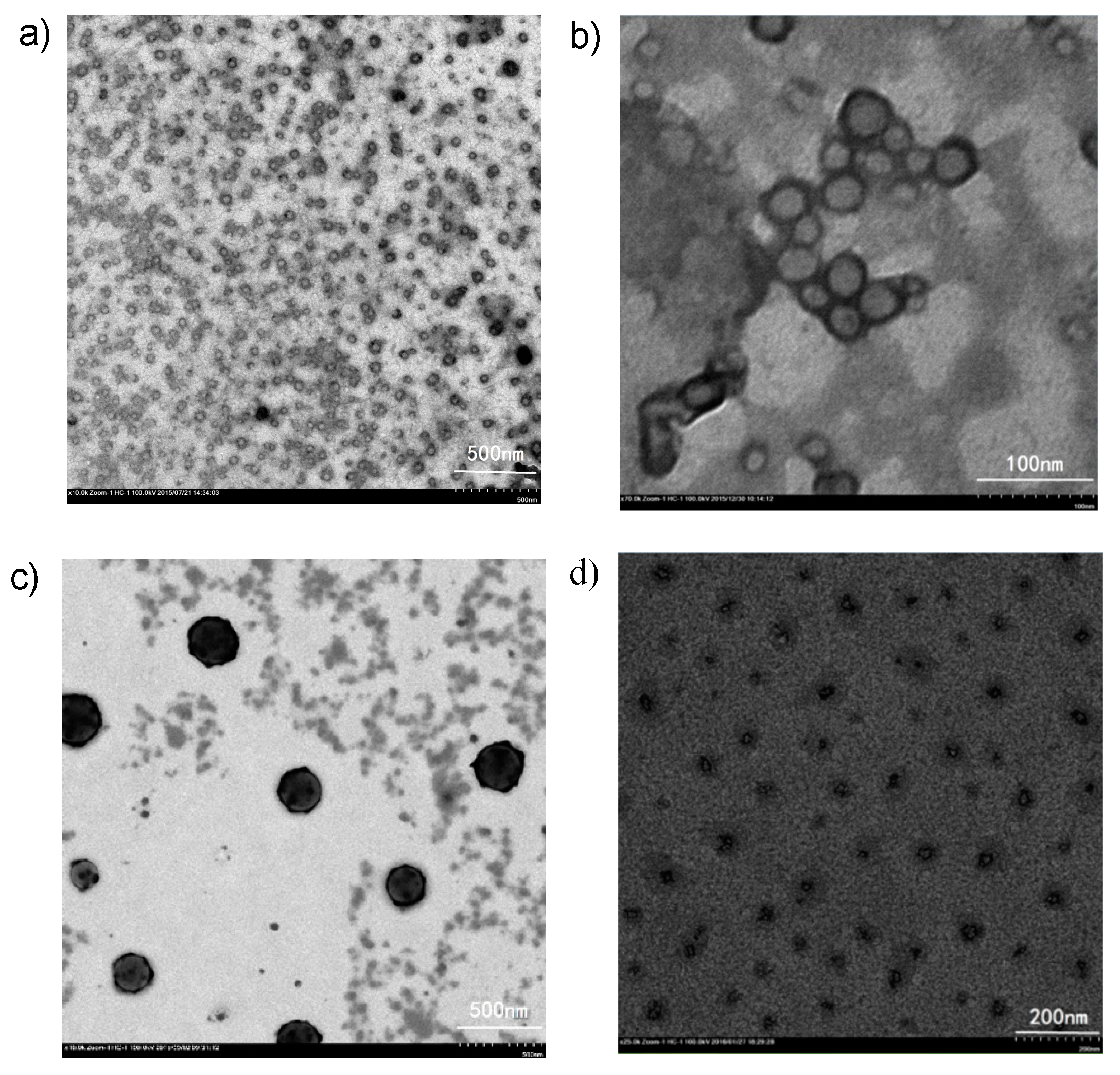

3.4. Self-Assembly of PS-Se-1-b-PEGMA950 Before and After Oxidation

3.5. Cytotoxicity Test

3.6. Drug Loading and Oxidation-Responsive Drug Release

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wirth, T. Organoselenium Chemistry: Modern Developments in ORGANIC Synthesis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000; Volume 208. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.H.; Li, T.Y.; Lu, C.J.; Xu, H.P. Selenium-Containing Polymers: Perspectives toward Diverse Applications in Both Adaptive and Biomedical Materials. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7435–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.P.; Cao, W.; Zhang, X. Selenium-Containing Polymers: Promising Biomaterials for Controlled Release and Enzyme Mimics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketia-Yawson, B.; Jung, A.R.; Nguyen, H.D.; Lee, K.K.; Kim, B.; Noh, Y.Y. Difluorobenzothiadiazole and Selenophene-Based Conjugated Polymer Demonstrating an Effective Hole Mobility Exceeding 5 cm(2) V-1 s(-1) with Solid-State Electrolyte Dielectric. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 32492–32500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.Q.; Li, M.M.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, H.K.; Geng, Y.H. Near-infrared absorbing non-fullerene acceptors with selenophene as pi bridges for efficient organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 8059–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Song, E.; Lee, S.B.; Kang, I.N.; Cho, K.; Hwang, D.H. Effect of methyl substitution on the diketopyrrolopyrrole-based semiconducting polymers for organic thin film transistors. Org. Electron. 2018, 56, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.J.; Shi, G.Z.; Yuan, J.Y.; Glenn, E.; Wang, H.Q.; Ma, W.L. New Semiconducting Polymer Based on Benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b′]diselenophene Donor and Diketopyrrolopyrrole/Isoindigo Acceptor Unit: Synthesis, Characterization and Photovoltaics. Chin. J. Chem. 2015, 33, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, R.S.; Meager, I.; Nikolka, M.; Kirkus, M.; Planells, M.; Schroeder, B.C.; Holliday, S.; Hurhangee, M.; Nielsen, C.B.; Sirringhaus, H.; et al. Chalcogenophene Comonomer Comparison in Small Band Gap Diketopyrrolopyrrole-Based Conjugated Polymers for High-Performing Field-Effect Transistors and Organic Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; An, T.K.; Hong, J.A.; Yun, H.J.; Kim, R.; Chung, D.S.; Park, C.E.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, S.K. Effect of Selenophene in a DPP Copolymer Incorporating a Vinyl Group for High-Performance Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Tsai, C.E.; Lai, Y.Y.; Liang, W.W.; Hsu, S.L.; Hsu, C.S.; Cheng, Y.J. A New Pentacyclic Indacenodiselenophene Arene and Its Donor-Acceptor Copolymers for Solution-Processable Polymer Solar Cells and Transistors: Synthesis, Characterization, and Investigation of Alkyl/Alkoxy Side-Chain Effect. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 7715–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Son, S.K.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.K.; Shin, W.S.; Moon, S.J.; Kang, I.N. Synthesis and Characterization of New Selenophene-Based Donor-Acceptor Low-Bandgap Polymers for Organic Photovoltaic Cells. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khim, D.; Lee, W.H.; Baeg, K.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Kang, I.N.; Noh, Y.Y. Highly stable printed polymer field-effect transistors and inverters via polyselenophene conjugated polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 12774–12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.B.; Cao, W.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.P. Visible-Light-Induced Self-Healing Diselenide-Containing Polyurethane Elastomer. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7740–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.B.; Fan, F.Q.; Sun, C.X.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.P. Visible Light-Induced Plasticity of Shape Memory Polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 33169–33175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.N.; Jin, Y.; Lai, S.Q.; Shi, L.J.; Fan, W.H.; Pan, J.Z. Near-infrared light triggered shape memory and self-healable polyurethane/ functionalized graphene oxide composites containing diselenide bonds. Polymer 2018, 158, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.W.; Aguirresarobe, R.H.; Irusta, L.; Ruiperez, F.; Matxain, J.M.; Pan, X.Q.; Aramburu, N.; Mecerreyes, D.; Sardon, H.; Zhu, J. Aromatic diselenide crosslinkers to enhance the reprocessability and self-healing of polyurethane thermosets. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 3641–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemeskel, B.Z.; Addisu, K.D.; Prasannan, A.; Mekuria, S.L.; Kao, C.Y.; Tsai, H.C. Synthesis and characterization of diselenide linked poly(ethylene glycol) nanogel as multi-responsive drug carrier. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 449, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Ma, N.; Ren, H.F.; Xu, H.P.; Li, Z.B.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, X. Oxidation-Responsive Micelles Based on a Selenium-Containing Polymeric Superamphiphile. Langmuir 2010, 26, 14414–14418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.K.; Chen, Q.X.; Lu, H.G.; An, J.X.; Zhu, H.J.; Yan, X.J.; Li, W.; Gao, H. Near-infrared AIEgen-functionalized and diselenide-linked oligo-ethylenimine with self-sufficing ROS to exert spatiotemporal responsibility for promoted gene delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 6660–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, S.A.; Patil, M.P.; Kim, D.W.; Le, C.M.Q.; Ahn, B.H.; Kim, G.D.; Lim, K.T. Near-infrared light-responsive, diselenide containing core-cross-linked micelles prepared by the Diels-Alder click reaction for photocontrollable drug release application. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 4813–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.B.; Zhu, C.Z.; Xu, J. Multiple stimuli-responsive selenium-functionalized biodegradable starch-based hydrogels. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.H.; Ji, S.B.; Xu, H.P. Diselenide covalent chemistry at the interface: Stabilizing an asymmetric diselenide-containing polymer via micelle formation. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6708–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, S.A.; Le, C.M.Q.; Kim, D.W.; Cao, X.T.; Jeong, Y.T.; Lim, K.T. Synthesis and characterization of diselenide crosslinked polymeric micelles via Diels-Alder click reaction. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2018, 662, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, H.; Bolton, E.F. Synthesis of Selenium Condensation Polymers Using Bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) Selenide and Bis(2-Aminoethyl) Selenide. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1970, 14, 2319–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuten, B.T.; Bloesser, F.R.; Marshall, D.L.; Michalek, L.; Schmitt, C.W.; Blanksby, S.J.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Polyselenoureas via Multicomponent Polymerizations Using Elemental Selenium as Monomer. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Li, Y.; Ren, H.F.; Xu, H.P.; Li, Z.B.; Zhang, X. Selenium-containing block copolymers and their oxidation-responsive aggregates. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, W.H.H.; Salzman, M.N. Methods in Selenium Chemistry 4. Synthetic Approaches to Polydiselenides. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1972, 192, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.P.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, X. Dual Redox Responsive Assemblies Formed from Diselenide Block Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiefari, J.; Chong, Y.K.; Ercole, F.; Krstina, J.; Jeffery, J.; Le, T.P.T.; Mayadunne, R.T.A.; Meijs, G.F.; Moad, C.L.; Moad, G.; et al. Living free-radical polymerization by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer: The RAFT process. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5559–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.S.; Takagi, K.; Kunisada, H.; Yuki, Y. Synthesis of star polystyrene by radical polymerization with 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(p-tert-butylphenylselenomethyl)benzene as a novel photoiniferter. Eur. Polym. J. 2003, 39, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Z.P.; Zhu, X.L. New Selenium-Based Iniferter Agent for Living Free Radical Polymerization of Styrene Under UV Irradiation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 2211–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, D.J. A guide to the synthesis of block copolymers using reversible-addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.L. Facile synthesis of well-defined redox responsive diselenide-labeled polymers via organoselenium-mediated CRP and aminolysis. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.X.; Lu, W.H.; Gao, F.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhu, X.L. Diselenide-Labeled Cyclic Polystyrene with Multiple Responses: Facile Synthesis, Tunable Size, and Topology. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2016, 37, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, B.K.; Du, Z.Z.; Lang, M.D. A Versatile Strategy to Main Chain Sulfur/Selenium-Functionalized Polycarbonates by Macro-Ring Closure of Diols and Subsequent Ring-Opening Polymerization. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.Q.; Driessen, F.; Zhu, X.L.; Du Prez, F.E. Selenolactone as a Building Block toward Dynamic Diselenide-Containing Polymer Architectures with Controllable Topology. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Xu, Y.; Yan, B.K.; Hou, J.Q.; Du, Z.Z.; Lang, M.D. Well-Defined Selenium-Containing Aliphatic Polycarbonates via Lipase-Catalyzed Ring-Opening Polymerization of Selenic Macrocyclic Carbonate Monomer. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.D.; Zhu, J.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhou, N.C.; Cheng, Z.P.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.L. Organoselenium compounds: Development of a universal "living" free radical polymerization mediator. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 3453–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.H.; An, X.W.; Gao, F.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, N.C.; Zhang, Z.B.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhu, X.L. Highly Efficient Chain End Derivatization of Selenol-Ended Polystyrenes by Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2017, 218, 1600485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Huo, F.; Xu, H.P. Selenium-Containing Polymer@Metal-Organic Frameworks Nanocomposites as an Efficient Multiresponsive Drug Delivery System. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1605465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Time (h) | Conv. (%) | Mn,SECa (g mol−1) | Mn,thb (g mol−1) | Mn,NMRc (g mol−1) | Ð a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (PS-Se-1) | 2 | 27.6 | 1900 | 1800 | 2100 | 1.20 |

| 2 (PS-Se-2) | 4 | 37.5 | 4200 | 4200 | 4400 | 1.17 |

| Entry | Time (d) | Catalyst | R b | Conv. c (%) | Mn,SECd (g mol−1) | Ð d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | - | 1:1 | 24.8 | 3100 | 1.14 |

| 2 | 2 | - | 1:1 | 23.0 | 3400 | 1.11 |

| 3 | 4 | - | 1:1 | 50.0 | 3500 | 1.12 |

| 4 | 6 | - | 1:1 | 31.7 | 3400 | 1.11 |

| 5 e | 4 | - | 1:1 | 22.4 | 3700 | 1.10 |

| 6 f | 4 | - | 1:1 | 14.6 | 3700 | 1.11 |

| 7 | 4 | 10% DBU | 1:1 | 25.9 | 3500 | 1.10 |

| 8 | 4 | 10% Et3N | 1:1 | 22.8 | 3400 | 1.11 |

| 9 | 4 | - | 1:2 | 64.0 | 3500 | 1.11 |

| 10 | 4 | - | 1:10 | 85.0 | 3700 | 1.11 |

| 11 | 4 | - | 1:50 | 46.0 | 3500 | 1.12 |

| Entry | PEGMA (g mol−1) | Conv. (%) a | Mn,SEC (g mol−1) b | Ð b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (PS-Se-1-b-PEGMA320) | 320 | 95.4 | 2700 | 1.09 |

| 2 (PS-Se-1-b-PEGMA500) | 500 | 90.2 | 3200 | 1.09 |

| 3 (PS-Se-1-b-PEGMA950) | 950 | 85.0 | 3700 | 1.11 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, X.; Lu, W.; Zhu, J.; Pan, X.; Zhu, X. Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction for the Preparation of Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers. Polymers 2019, 11, 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11050827

An X, Lu W, Zhu J, Pan X, Zhu X. Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction for the Preparation of Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers. Polymers. 2019; 11(5):827. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11050827

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Xiaowei, Weihong Lu, Jian Zhu, Xiangqiang Pan, and Xiulin Zhu. 2019. "Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction for the Preparation of Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers" Polymers 11, no. 5: 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11050827

APA StyleAn, X., Lu, W., Zhu, J., Pan, X., & Zhu, X. (2019). Selenol-Based Nucleophilic Reaction for the Preparation of Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers. Polymers, 11(5), 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11050827