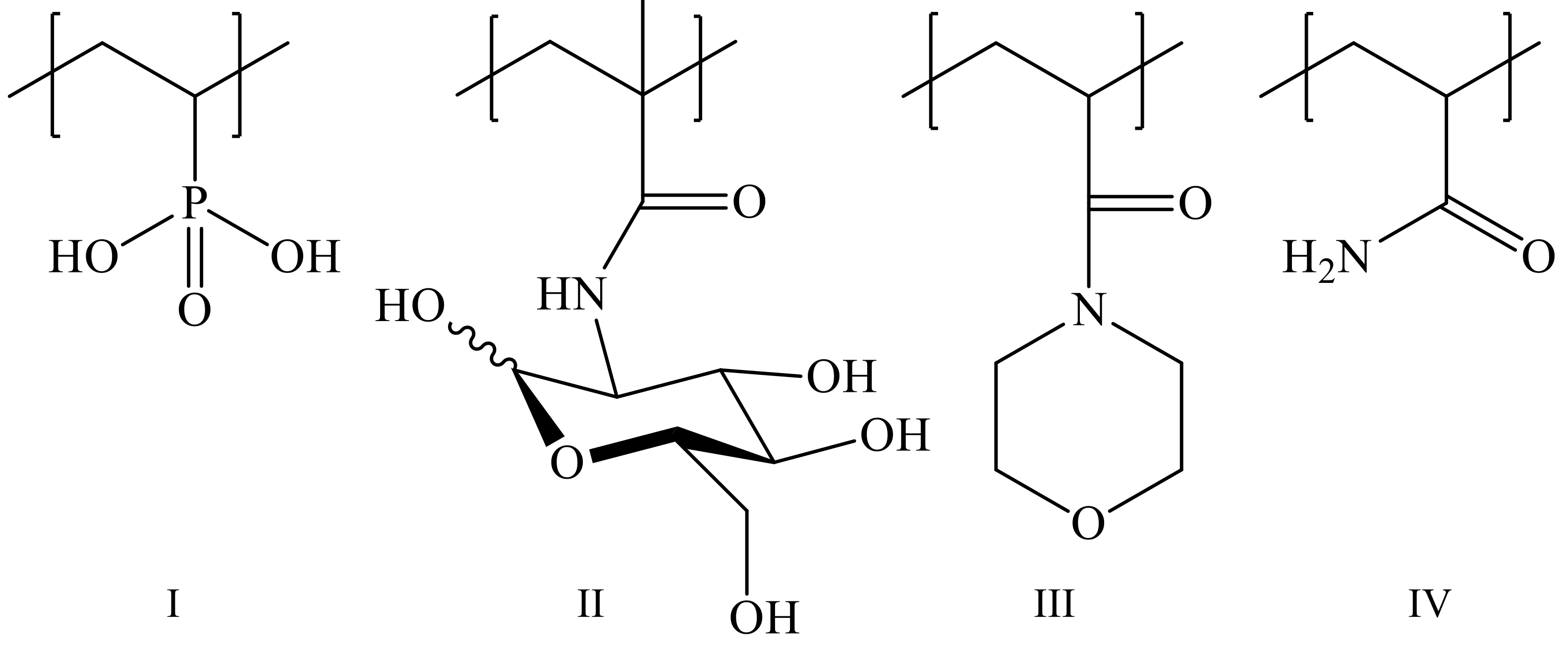

New Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid with Hydrophilic Monomers and Their Eu3+ Complexes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of (Co)Polymers

2.2.2. Compositions of Copolymers

2.2.3. IR Spectroscopy

2.2.4. Determination of Molecular Masses of Polymers

2.2.5. Synthesis of Complexes with Eu3+

2.2.6. UV-Vis Spectra

2.2.7. Excitation and Luminescence Spectra

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macarie, L.; Ilia, G. Poly(Vinylphosphonic Acid) and Its Derivatives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingratta, M.; Elomaa, M.; Jannasch, P. Grafting Poly(Phenylene Oxide) with Poly(Vinylphosphonic Acid) for Fuel Cell Membranes. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Anstice, M.; Wilson, A.D. The Glass Polyphosphonate Cement: A Novel Glass-Ionomer Cement Based on Poly(Vinyl Phosphonic Acid). Clin. Mater. 1991, 7, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.E.; Zhong, X.; Youle, P.J.; Wang, Q.G.; Wimpenny, I.; Downes, S.; Hoyland, J.A.; Watts, D.C.; Gough, J.E.; Budd, P.M. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Vinylphosphonic Acid- Co -Acrylic Acid) Copolymers for Application in Bone Tissue Scaffolds. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2656–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Young, D.J.; Liu, M.; Wu, C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Loh, X.J. Toward the Prevention of Coronavirus Infection: What Role Can Polymers Play? Mater. Today Adv. 2021, 10, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandock, F.; Riber, C.F.; Röcker, A.; Müller, J.A.; Harms, M.; Gajda, P.; Zuwala, K.; Andersen, A.H.F.; Løvschall, K.B.; Tolstrup, M.; et al. Macromolecular Antiviral Agents against Zika, Ebola, SARS, and Other Pathogenic Viruses. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivas, B.L.; Pereira, E.; Gallegos, P.; Homper, D.; Geckeler, K.E. Metal Ion Binding Capability of the Water-Soluble Poly(Vinyl Phosphonic Acid) for Mono-, Di-, and Trivalent Cations. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 92, 2917–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzoun-Zada, S.; Jaber, Q.Z.; Fridman, M. Guiding Drugs to Target-Harboring Organelles: Stretching Drug-Delivery to a Higher Level of Resolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15584–15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünzli, J.-C.G. Lanthanide Light for Biology and Medical Diagnosis. J. Lumin. 2016, 170, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, J.; Minko, T. Polymer–Drug Conjugates: Progress in Polymeric Prodrugs. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 359–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clearfield, A. Coordination Chemistry of Phosphonic Acids with Special Relevance to Rare Earths. J. Alloys Compd. 2006, 418, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, S.I. Intramolecular Energy Transfer the Fluorescence of Complexes of Europium. J. Chem. Phys. 1942, 10, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utochnikova, V.V. The Use of Luminescent Spectroscopy to Obtain Information about the Composition and the Structure of Lanthanide Coordination Compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 398, 113006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasova, T.N.; Zhuravskaya, O.N.; Bezrukova, M.A.; Dobrodumov, A.V.; Panarin, E.F. Water-Soluble Polymer Ligands for Binding of Terbium Ions. Dokl. Chem. 2020, 492, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Akar, A.; Köken, N.; Kızılcan, N. Polymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid, Acrylonitrile, and Methyl Acrylate and Their Nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, B.; Strandberg, C.; Szabo, A.; Wegner, G. Copolymers and Hydrogels Based on Vinylphosphonic Acid. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 2785–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Jang, J. Synergistic UV-Curable Flame-Retardant Finish of Cotton Using Comonomers of Vinylphosphonic Acid and Acrylamide. Fibers Polym. 2017, 18, 2328–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavlak, S.; Güner, A.; Rzayev, Z.M.O. Functional Terpolymers Containing Vinylphosphonic Acid: The Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Vinylphosphonic Acid-Co-Styrene-Co-Maleic Anhydride). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 3617–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemi, H.; Bozkurt, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Vinylpyrrolidone-Co-Vinylphosphonic Acid) Copolymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2004, 40, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Meyer, W.H.; Gutmann, J.; Wegner, G. Proton Conducting Copolymers on the Basis of Vinylphosphonic Acid and 4-Vinylimidazole. Solid State Ion. 2003, 164, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Manhart, A.; Deniz, N.; Kaltbeitzel, A.; Wagner, M.; Brunklaus, G.; Meyer, W.H. Vinylphosphonic Acid Homo- and Block Copolymers: Vinylphosphonic Acid Homo- and Block Copolymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2009, 210, 1903–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzhikov, V.A.; Diederichs, S.; Nazarova, O.V.; Vlakh, E.G.; Kasper, C.; Panarin, E.F.; Tennikova, T.B. Water-Soluble Aldehyde-Bearing Polymers of 2-Deoxy-2-Methacrylamido-D-Glucose for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 108, 2386–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, V.N. Transport Methods. In Rigid-Chain Polymers. Hydrodynamic and Optical Properties in Solution; Consultants Bureau: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 87–146. ISBN 978-0-306-11020-7. [Google Scholar]

- Macarie, L.; Pekar, M.; Simulescu, V.; Plesu, N.; Iliescu, S.; Ilia, G.; Tara-Lunga-Mihali, M. Properties in Aqueous Solution of Homo- and Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid Derivatives Obtained by UV-Curing. Macromol. Res. 2017, 25, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamai, R.; Shirosaki, Y.; Miyazaki, T. Biomineralization Behavior of a Vinylphosphonic Acid-Based Copolymer Added with Polymerization Accelerator in Simulated Body Fluid. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2015, 3, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nandi, U.S.; Ghosh, P.; Palit, S.R. Water as a Chain-Transferring Agent in Vinyl Polymerization. Nature 1962, 195, 1197–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelyukh, A.I.; Ushakova, V.N.; Panarin, E.F. Effect of Solvent on Molecular Weight of Polyvinylpyrrolidone in Radiation-Initiated Vinylpyrrolidone Polymerization with Low Conversions. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 1995, 68, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, M.; Ross, S.D. Linear Method for Determining Monomer Reactivity Ratios in Copolymerization. J. Polym. Sci. 1950, 5, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelen, T.; TÜd[Otilde]s, F. Analysis of the Linear Methods for Determining Copolymerization Reactivity Ratios. I. A New Improved Linear Graphic Method. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A—Chem. 1975, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, B.; Meyer, W.H.; Wagner, M.; Wegner, G. Synthesis, Microstructure, and Acidity of Poly(Vinylphosphonic Acid). Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 1719–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latva, M.; Takalo, H.; Mukkala, V.-M.; Matachescu, C.; Rodríguez-Ubis, J.C.; Kankare, J. Correlation between the Lowest Triplet State Energy Level of the Ligand and Lanthanide(III) Luminescence Quantum Yield. J. Lumin. 1997, 75, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, N.; Georges, J. Comprehensive Study of the Luminescent Properties and Lifetimes of Eu3+ and Tb3+ Chelated with Various Ligands in Aqueous Solutions: Influence of the Synergic Agent, the Surfactant and the Energy Level of the Ligand Triplet. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2003, 59, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinovskaya, I.V. Spectral-Luminescence Properties of Europium(III) Compounds with Two Different β-Diketones. Opt. Spectrosc. 2018, 124, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, K.P.; Tsaryuk, V.I.; Pekareva, I.S.; Sokolnicki, J.; Klemenkova, Z.S. Europium and Terbium Ortho-, Meta-, and Para-Methoxybenzoates: Structural Peculiarities, Luminescence, and Energy Transfer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2011, 219, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaryuk, V.I.; Zhuravlev, K.P.; Vologzhanina, A.V.; Kudryashova, V.A.; Zolin, V.F. Structural Regularities and Luminescence Properties of Dimeric Europium and Terbium Carboxylates with 1,10-Phenanthroline (CN = 9). J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2010, 211, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Conditions of Copolymerization a | Characteristics of Copolymers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M2] | [M1]:[M2], mol.% | [M1 + M2], wt.% | Solvent | I b | [I], wt.% of [M1 + M2] | Yield, % | [M1], mol.% | MSD × 10−3 | |

| 1 c | – | 100:0 | 80 | H2O | AMP | 1 | 54 | 100 | 30 |

| 2 | MAG | 25:75 | 10 | H2O | AMP | 2 | 86 | 6 | 117 |

| 3 | MAG | 50:50 | 10 | DMFA | AIBN | 2 | 71 | 12 | 20 |

| 4 | MAG | 90:10 | 10 | H2O | AMP | 2 | 29 | 53 | 5 |

| 5 | 4-AM | 25:75 | 20 | Methanol | AIBN | 2 | 76 | 13 | 77 |

| 6 | 4-AM | 25:75 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 2 | 82 | 14 | 310 |

| 7 | 4-AM | 50:50 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 1 | 38 | 56 | 33 |

| 8 | 4-AM | 90:10 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 1 | 27 | 97 | 10 |

| 9 | AA | 25:75 | 20 | Methanol | AIBN | 2 | 77 | 13 | 40 |

| 10 | AA | 25:75 | 20 | DMFA | AIBN | 2 | 93 | 28 | 25 |

| 11 | AA | 25:75 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 2 | 74 | 14 | 240 |

| 12 | AA | 50:50 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 1 | 56 | 31 | 70 |

| 13 | AA | 90:10 | 20 | H2O | AMP | 1 | 11 | 63 | 7 |

| Solution | I614 (U = 400) |

|---|---|

| Eu3+/4-AM-VPA copolymer | n/d |

| Eu3+/TTA | 1 |

| Eu3+/PHEN | <1 |

| Eu3+/4-AM-VPA copolymer/TTA | 186 |

| Eu3+/4-AM-VPA copolymer/PHEN | 72 |

| Eu3+/4-AM-VPA copolymer/TTA/PHEN | 2434 |

| N (Table 1) | M2 | I614 Copolymer/TTA | I614 Copolymer/TTA/PHEN | ITTA+PHEN/ITTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4-AM | 92 | 1272 | 14 |

| 3 | MAG | 18 | 944 | 52 |

| 11 | AA | 3 | 204 | 68 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazarova, O.; Chesnokova, E.; Nekrasova, T.; Zolotova, Y.; Dobrodumov, A.; Vlasova, E.; Fischer, A.; Bezrukova, M.; Panarin, E. New Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid with Hydrophilic Monomers and Their Eu3+ Complexes. Polymers 2022, 14, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030590

Nazarova O, Chesnokova E, Nekrasova T, Zolotova Y, Dobrodumov A, Vlasova E, Fischer A, Bezrukova M, Panarin E. New Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid with Hydrophilic Monomers and Their Eu3+ Complexes. Polymers. 2022; 14(3):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030590

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazarova, Olga, Elena Chesnokova, Tatyana Nekrasova, Yulia Zolotova, Anatoliy Dobrodumov, Elena Vlasova, Andrei Fischer, Marina Bezrukova, and Eugeniy Panarin. 2022. "New Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid with Hydrophilic Monomers and Their Eu3+ Complexes" Polymers 14, no. 3: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030590

APA StyleNazarova, O., Chesnokova, E., Nekrasova, T., Zolotova, Y., Dobrodumov, A., Vlasova, E., Fischer, A., Bezrukova, M., & Panarin, E. (2022). New Copolymers of Vinylphosphonic Acid with Hydrophilic Monomers and Their Eu3+ Complexes. Polymers, 14(3), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030590