Post-Consumer Recycled PET: A Comprehensive Review of Food and Beverage Packaging Safety in Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Production of Virgin PET

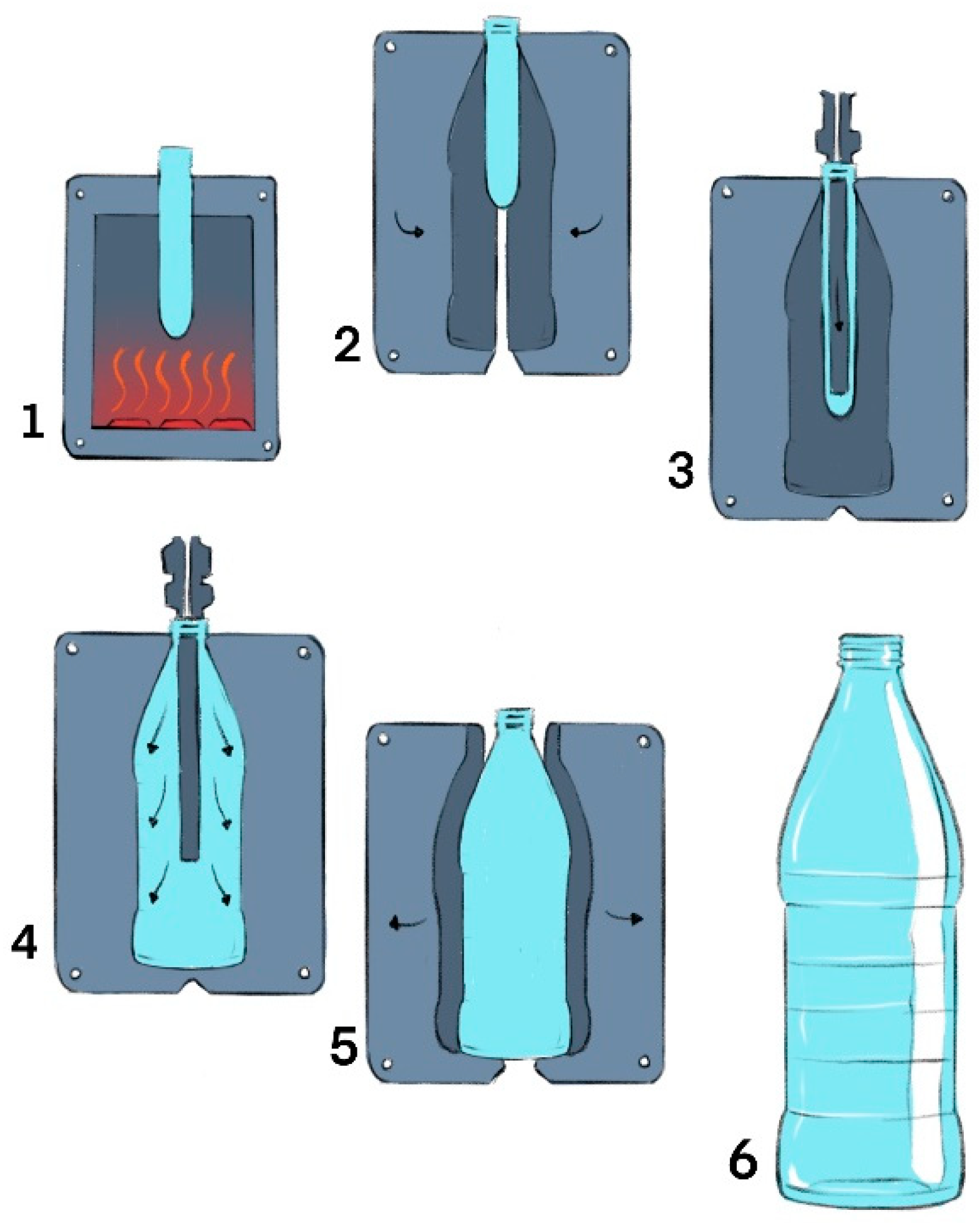

3. Injection and Blow Molding

4. Reverse Logistics

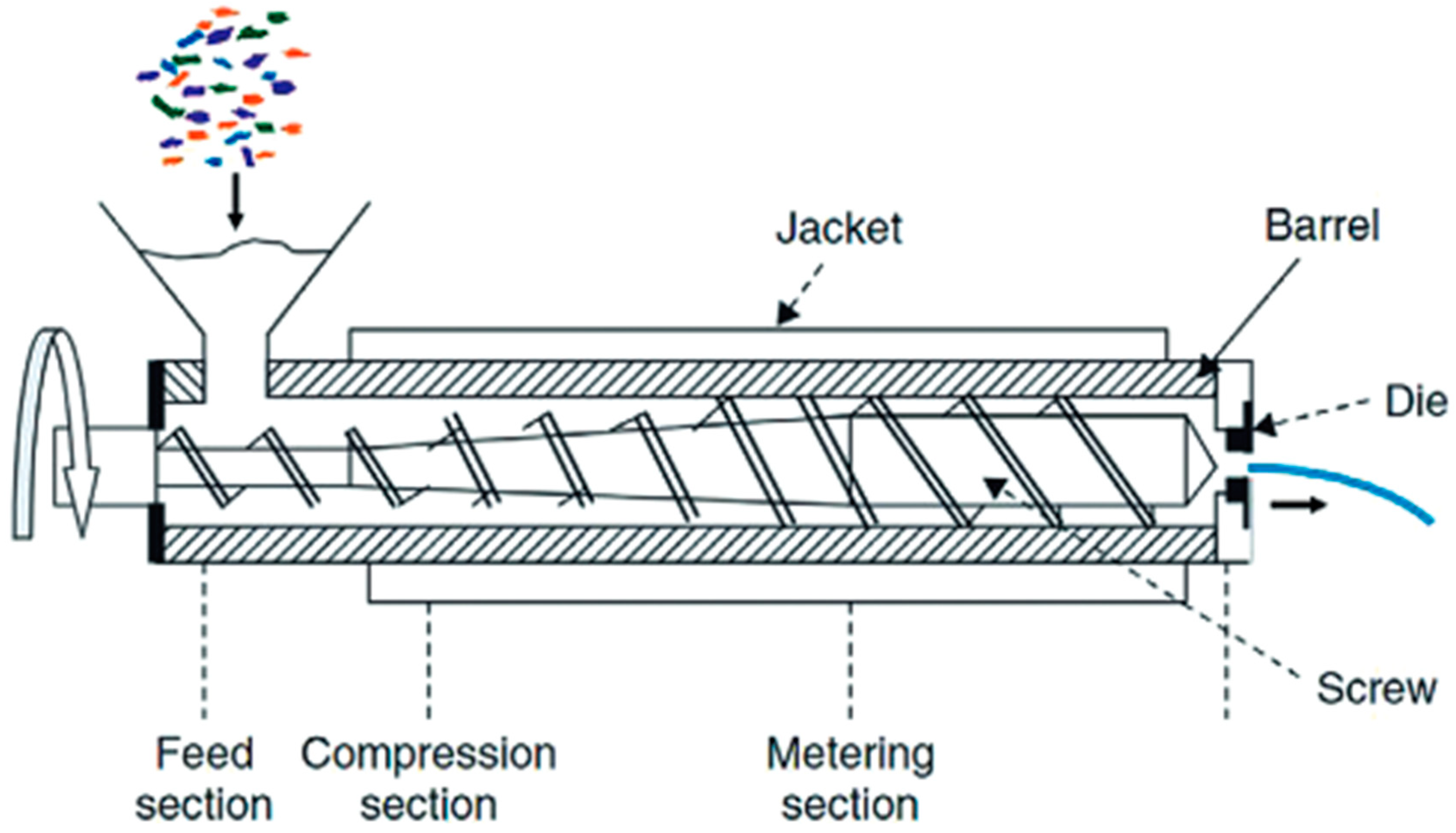

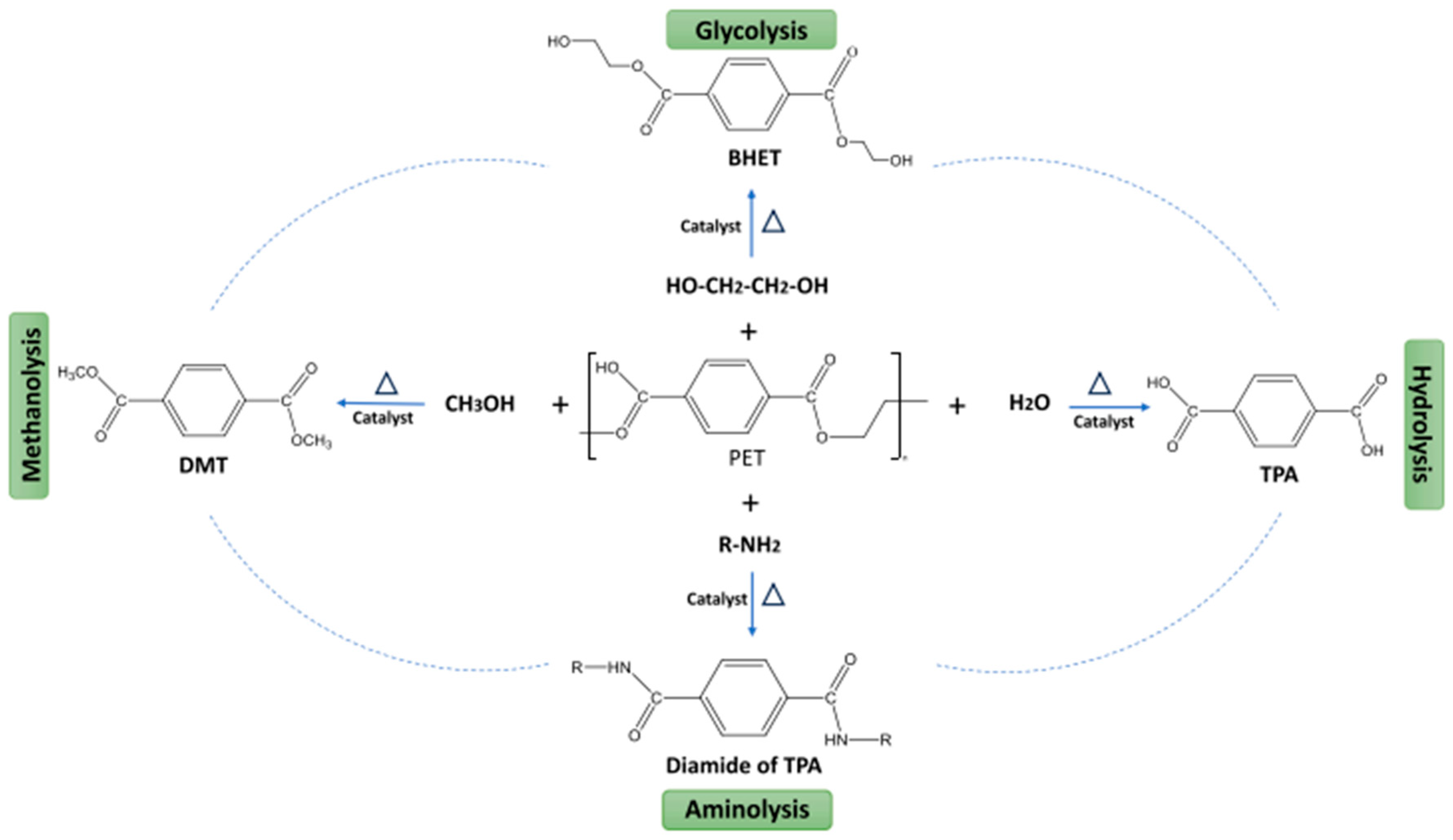

5. Mechanical and Chemical Recycling of PET

6. Legislation and Contaminants of PET-PCR

6.1. Positive List and Migration Limits of Contaminants from Virgin PET and PCR

6.2. Requirements for the Safety of Food Contact Packaging

6.3. Challenge Test of PET-PCR for Food Contact

6.4. Requirements for Notification to ANVISA of Food-Grade PET-PCR Resin and Food-Grade PET-PCR Packaging

- (a)

- Recycling technology with high decontamination efficiency;

- (b)

- Food-grade PET-PCR resin;

- (c)

- Food-grade PET-PCR packaging or precursor article for food-grade PET-PCR packaging.

- (a)

- Technology involved: detailed description of the physical and/or chemical recycling technologies applied to the processing of post-consumer PET and/or industrial waste.

- (b)

- International background: history of the use of these technologies in other countries, highlighting the regulations and practices adopted to ensure the quality of recycled PET.

- (c)

- Technology validation: results of validation tests (such as challenge tests) demonstrating the effectiveness of the technology in removing contaminants, recognized by entities such as the FDA (USA) and EFSA (European Union).

- (d)

- Letters of no objection: documents issued by agencies such as the FDA that attest to the safety of using food-grade PET-PCR resin, validating the technology and ensuring the safety of the recycled material for food contact.

- (a)

- Process flowchart: specification of the equipment and processes used in the manufacture of the packaging or precursor article.

- (b)

- Material specification: details about the PET-PCR resin (supplier and notification to ANVISA), additives, and pigments used.

- (c)

- Type of packaging: statement regarding the type of packaging to be produced and its conditions of use (single-layer, returnable, etc.).

- (d)

- Food specification: details of the foods to be packaged and the percentages of PET-PCR resin, pigments, and additives.

- (e)

- Analysis reports: results of total and specific migration (monomers, acetaldehyde, metals, aromatic amines) and volatile profile.

- (f)

- Notification form: completed according to the ANVISA model.

- (g)

- Sanitary licensing: document from the manufacturer proving compliance with the health authority.

6.5. Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIASs) in PET-PCR

| Origin | Food/Food Simulant | NIAS | Highlights | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 3% (m/v) acetic acid solution in water. 10% (v/v) ethanol solution in water. 95% (v/v) ethanol solution in water. | Cyclic and linear oligomers. |

| [77] |

| Netherlands | Mineral water. | 2-methyl-1,3-dioxolane, limonene, acetone, butanone, furan, benzene and styrene. |

| [78] |

| Denmark | Parmesan cheese, sausages, roast chicken. | Acetophenone, benzophenone, 1-hydroxycyclohexyl-1-phenylketone, acetaldehyde, acetophenone, 2-methyl-1,3-dioxolane, benzene, styrene, hexadecenamide, edodecenamide and oligomers. |

| [79] |

| China | Recycled PET flakes with solvent. | Naphthalene-d8, dimethyl terephthalate, diisobutyl thalate, methyl stearate, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, benzothiazole, dimethyl phthalate, 1,2-diphenoxyethane, 2-hydroxyethylmethyl terephthalate, ethylene terephthalate cyclic dimer, benzene and substituted derivatives. |

| [75] |

| Brazil | 3% (m/v) acetic acid solution in water. 10% (v/v) ethanol solution in water. 95% (v/v) ethanol solution in water. | Bis(7-methyloctyl) hexanedioate, 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid diisononyl ester, 2,5-bis(5-tert-butyl-2-benzoxazolylthiophene, (Z)-octadec-9-enamide |

| [80] |

7. Future Perspectives for PET-PCR

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okunola, A.A.; Kehinde, I.O.; Oluwaseun, A.; Olufiropo, E.A. Public and Environmental Health Effects of Plastic Wastes Disposal: A Review. J. Toxicol. Risk Assess. 2019, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Verma, A.; Shome, A.; Sinha, R.; Sinha, S.; Jha, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Shubham; Das, S.; et al. Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Ecosystem Services, Sustainable Development Goals, and Need to Focus on Circular Economy and Policy Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L.; Coltro, L.; Dantas, F.B.; Vieira, R.P. Research on Food Packaging and Storage. Coatings 2022, 12, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Bedi, R.; Kaith, B.S. Composite Materials Based on Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate and Their Properties–A Comprehensive Review. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 219, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, R. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) in the Packaging Industry. Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda, P.; Hanan, J.C.; Lawrence, J.G.; Allahkarami, M. Sustainability Performance of Polyethylene Terephthalate, Clarifying Challenges and Opportunities. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombre, C.; Rigou, P.; Wirth, J.; Chalier, P. Aromatic Evolution of Wine Packed in Virgin and Recycled PET Bottles. Food Chem. 2015, 176, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajaj, R.; Abu Jadayil, W.; Anver, H.; Aqil, E. A Revision for the Different Reuses of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Water Bottles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, C.; Purbey, R.; Bora, D.; Chetia, P.; Maheswari, R.U.; Duarah, R.; Dutta, K.; Sadiku, E.R.; Varaprasad, K.; Jayaramudu, J. A Review on Sustainable PET Recycling: Strategies and Trends. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Resolução de Diretoria Colegiada (RDC) N°20, de 26 de Março de 2008; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira da Indústria do PET (ABIPET) Reciclagem de PET Mantém Crescimento Mesmo com os Desafios da Coleta Seletiva. Available online: https://abipet.org.br (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- FDA. Use of Recycled Plastics in Food Packaging (Chemistry Considerations): Guidance for Industry; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bezeraj, E.; Debrie, S.; Arraez, F.J.; Reyes, P.; Van Steenberge, P.H.M.; D’hooge, D.R.; Edeleva, M. State-of-the-Art of Industrial PET Mechanical Recycling: Technologies, Impact of Contamination and Guidelines for Decision-Making. RSC Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigotti, R.; Giannone, N.; Asteggiano, A.; Mecarelli, E.; Dal Bello, F.; Medana, C. Release of Selected Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS) from PET Food Contact Materials: A New Online SPE-UHPLC-MS/MS Multiresidue Method. Separations 2022, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, A.; Kishi, E.; Ooshima, T.; Kakutani, N.; Abe, Y.; Mutsuga, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yamano, T. Determination of Potential Volatile Compounds in Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottles and Their Short- and Long-Term Migration into Food Simulants and Soft Drink. Food Chem. 2022, 397, 133758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimel, K.G.; Hwang, R.; Dinh, D.; Donnell, M.T.; More, S.; Fung, E. Evaluation of Chemicals Leached from PET and Recycled PET Containers into Beverages. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreier, V.N.; Odermatt, A.; Welle, F. Migration Modeling as a Valuable Tool for Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization of Polyethylene Terephthalate Oligomers. Molecules 2022, 28, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, B.; Kusano, Y.; Cederberg, T.L.; Jensen, L.K.; Granby, K.; Pedersen, G.A. Chemical Characterization of Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate Films Used for Food Contact Applications. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, E.D.; Lopes, J.A.; Corredig, M. Chemical Testing of Mechanically Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate for Food Packaging in the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.E.; Lee, J. Polyethylene Terephthalate Production from a Carbon Neutral Resource. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 469, 143210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyataka, P.H.M.; Marangoni Júnior, L.; Brito, A.C.A.; Pallone, J.A.L. Migration of Antimony from Polyethylene Terephthalate Bottles to Mineral Water: Comparison between Test Conditions Proposed by Brazil and the European Union. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyataka, P.H.M.; Dantas, T.B.H.; Brito, A.C.A.; Júnior, L.M.; Pallone, J.A.L. Evaluation of Different Transport and Distribution Conditions on Antimony Migration from PET Bottles to Mineral Water. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 48, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaja, F.; Pavel, D. Recycling of PET. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 1453–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Robin, J.J.; Boutevin, B.; Re, C.E.; Ma, P. Study of thermal and mechanical properties of virgin and recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate) before and after injection molding. Eur. Polym. J. 1999, 36, 2075–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmann, D. PET Use in Blow Molded Rigid Packaging. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook: Processing, Sustainability, Materials, and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 809–835. ISBN 9780323886673. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel, B. Optimisation of Mould Surface Temperature and Bottle Residence Time in Mould for the Carbonated Soft Drink PET Containers. Polym. Test. 2017, 60, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, S.; Gugliuzzo, C.; Mirabella, E.F.; Puglisi, C.; Scamporrino, A.A.; Zampino, D.C.; Samperi, F. Characterization of VOCs and Additives in Italian PET Bottles and Studies on Potential Functional Aldehydes Scavengers. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga, H.H.; Sinha, D.K.; Getachew, A.; Workneh, M.; Rathee, D.S. Multi-Response Optimization of Process Parameters in Stretch Blow Molding of PET Plastic Bottles. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. D 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringayil Joseph, T.; Azat, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Moini Jazani, O.; Esmaeili, A.; Kianfar, E.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Recycling: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiler, B.C.; de Ignácio, P.S.A.; Pacagnella Júnior, A.C.; Anholon, R.; Rampasso, I.S. Reverse Logistics System Analysis of a Brazilian Beverage Company: An Exploratory Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, H.; Dey Sarkar, B.; Joshi, P.; Ghag, N.; Choubey, V.; Jagtap, S. Navigating Barriers to Reverse Logistics Adoption in Circular Economy: An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Development. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2024, 12, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, Y.; Siswanto, N.; Vanany, I. Reverse Logistics toward a Circular Economy: Consumer Behavioral Intention toward Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Recycling in Indonesia. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebehy, P.C.P.W.; Andrade dos Santos Lima, S.; Novi, J.C.; Salgado, A.P. Reverse Logistics Systems in Brazil: Comparative Study and Interest of Multistakeholders. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, T.M.; Castro, R.; Gobbo, J.A. PET Containers in Brazil: Opportunities and Challenges of a Logistics Model for Post-Consumer Waste Recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.L.; Chaves, G.d.L.D.; Ribeiro, G.M. Reverse Logistics Network for Municipal Solid Waste Management: The Inclusion of Waste Pickers as a Brazilian Legal Requirement. Waste Manag. 2015, 40, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri, P.; Cerqueira-Streit, J.A.; Batista, L.C. Reverse Logistics and the Sectoral Agreement of Packaging Industry in Brazil towards a Transition to Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABIPET as Etapas da Reciclagem. Available online: https://abipet.org.br (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Hoffmann, J.; Glückler, J. Technology Evolution in Heterogeneous Technological Fields: A Main Path Analysis of Plastic Recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, Y.-H.V.; Sobkowicz, M.J.; Xie, D. Recent Advances in Biological Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Plastic Wastes. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, N.A.S.; Muhamad, F.; Abd Razak, N.A.; Zeimaran, E. Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate Wastes: A Review of Technologies, Routes, and Applications. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 2355–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dul, S.; Lehner, S.; Jovic, M.; Gaan, S.; Heuberger, M.; Hufenus, R.; Gooneie, A. Mechanical Recycling of PET Containing Mixtures of Phosphorus Flame Retardants. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 194, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Worrell, E. Plastic Recycling. In Handbook of Recycling: State-of-the-Art for Practitioners, Analysts, and Scientists; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 497–510. ISBN 9780323855143. [Google Scholar]

- Plastics Recyclers Europe RecyClass-Recyclability Evaluation Protocol for PET Bottles. 2025. Available online: https://recyclass.eu/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Schyns, Z.O.G.; Shaver, M.P. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Morott, J.T.; Alshetaili, A.S.; Tiwari, R.V.; Majumdar, S.; Repka, M.A. Influence of Degassing on Hot-Melt Extrusion Process. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 80, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, J.-M.; Soltani, I.; Negrier, K.; Lee, P.C. Recyclability of Post-Consumer Polystyrene at Pilot Scale: Comparison of Mechanical and Solvent-Based Recycling Approaches. Polymers 2023, 15, 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachner, S.; Aigner, M.; Miethlinger, J. A Heuristic Method for Modeling the Initial Pressure Drop in Melt Filtration Using Woven Screens in Polymer Recycling. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2019, 59, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszun, D.; Spychaj, T. Chemical Recycling of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, M.; Jalilian, M.; Shahbaz, K. Chemical Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate: A Mini-Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Enayati, M. Dual Catalytic Activity of Antimony (III) Oxide: The Polymerization Catalyst for Synthesis of Polyethylene Terephthalate Also Catalyze Depolymerization. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 206, 110180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomasi, G.; Aquilino, R.; Brouwer, M.; De Gisi, S.; Smeding, I.; Todaro, F.; Notarnicola, M.; Thoden van Velzen, E.U. Strategies to Enhance the Circularity of Non-Bottle PET Packaging Waste Based on a Detailed Material Characterisation. Waste Manag. 2024, 186, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.H.; Auras, R.; Vorst, K.; Singh, J. An Exploratory Model for Predicting Post-Consumer Recycled PET Content in PET Sheets. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, H.; Schweiz, B. New Opportunities for PCR by Restabilization. 1995. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316715394_New_Opportunities_for_PCR_by_Restabilization (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Pinter, E.; Welle, F.; Mayrhofer, E.; Pechhacker, A.; Motloch, L.; Lahme, V.; Grant, A.; Tacker, M. Circularity Study on Pet Bottle-to-Bottle Recycling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-C.; Halley, P.J.; Gilbert, R.G. Mechanism of Degradation of Starch, a Highly Branched Polymer, during Extrusion. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2855–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, F.N.; Teófilo, E.T.; Rabello, M.S.; Silva, S.M.L. Chain Extension and Degradation during Reactive Processing of PET in the Presence of Triphenyl Phosphite. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2007, 47, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneie, A.; Simonetti, P.; Salmeia, K.A.; Gaan, S.; Hufenus, R.; Heuberger, M.P. Enhanced PET Processing with Organophosphorus Additive: Flame Retardant Products with Added-Value for Recycling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 160, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.M.; Berrard, C.; Daoud, N.; Saillard, P.; Peyroux, J.; Vitrac, O. Assessment of Chemical Risks and Circular Economy Implications of Recycled PET in Food Packaging with Functional Barriers. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.J.P.; Oliveira, D.S.B.L.; Oliveira, L.S.B.L.; Bezerra, B.S. Life Cycle Comparative Assessment of Pet Bottle Waste Management Options: A Case Study for the City of Bauru, Brazil. Waste Manag. 2021, 119, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRASIL. Informe Técnico n. 71, de 11 de Fevereiro de 2016; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- INMETRO. Regulamento Técnico Mercosul Sobre a Lista Positiva de Monômeros e Polímeros Autorizados Para a Elaboração de Embalagens e Equipamentos Plásticos Em Contato Com Alimentos; INMETRO: Brasília, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Resolução No 105, de 19 de Maio de 1999; Estabelece o Regulamento Técnico Sobre a Utilização de Materiais e Objetos Plásticos que Entrem em Contato com Alimentos; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil RDC No. 52, of November 23, 2010, Regulates the Use of Dyes in Plastic Packaging and Equipment Intended to Be in Contact with Food; National Health Surveillance Agency-ANVISA: Brasília, Brazil, 2010.

- Brazil Resolution RDC n 326 from 3 December 2019. Establishes the Positive List of Additives Intended for the Production of Plastic Materials and Polymeric Coatings in Contact with Food and Other Provisions; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

- Brazil Resolution RDC n 589 from 20 December 2021. Provides for Migration on Materials, Packaging and Plastic Equipment Intended to Come into Contact with Food; National Health Surveillance Agency-ANVISA: Brasília, Brazil, 2021.

- Paulo, H.M.; Marisa Padula, K. Requisitos Para Notificação Na Anvisa de Resina de PET-PCR Grau Alimentício e Embalagens de PET-PCR Grau Alimentício. Informativo 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Resolução de Diretoria Colegiada (RDC) N°51, de 26 de Novembro de 2010; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2010.

- Palkopoulou, S.; Joly, C.; Feigenbaum, A.; Papaspyrides, C.D.; Dole, P. Critical Review on Challenge Tests to Demonstrate Decontamination of Polyolefins Intended for Food Contact Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução RDC n° 843, de 22 de Fevereiro de 2024. In Regularização de Alimentos e Embalagens Sob Competência Do Sistema Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (SNVS) Destinados à Oferta No Território Nacional; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Instrução Normativa-IN n° 281, de 22 de Fevereiro de 2024. In Estabelece a Forma de Regularização Das Diferentes Categorias de Alimentos e Embalagens, e a Respectiva Documentação Que Deve Ser Apresentada; BRASIL: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lambré, C.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; Mengelers, M.; Mortensen, A.; et al. Scientific Guidance on the Criteria for the Evaluation and on the Preparation of Applications for the Safety Assessment of Post-consumer Mechanical PET Recycling Processes Intended to Be Used for Manufacture of Materials and Articles in Contact with Food. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodytska, O.; Cabanes, A.; Fullana, A. Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS) in Recycled Plastics. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undas, A.K.; Groenen, M.; Peters, R.J.B.; van Leeuwen, S.P.J. Safety of Recycled Plastics and Textiles: Review on the Detection, Identification and Safety Assessment of Contaminants. Chemosphere 2023, 312, 137175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxabide, A.; Young, B.; Bremer, P.J.; Kilmartin, P.A. Non-Permanent Primary Food Packaging Materials Assessment: Identification, Migration, Toxicity, and Consumption of Substances. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4130–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Miao, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y. Novel Selection of Recycled PET Surrogates Based on Non-Targeted Screening of Non-Intentionally Added Substances and Chemometrics. Microchem. J. 2024, 206, 111469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyathiar, P.; Kumar, P.; Carpenter, G.; Brace, J.; Mishra, D.K. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottle-to-Bottle Recycling for the Beverage Industry: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubeda, S.; Aznar, M.; Nerín, C. Determination of Oligomers in Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Samples by UPLC-MS-QTOF. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 2377–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoden van Velzen, E.U.; Brouwer, M.T.; Stärker, C.; Welle, F. Effect of Recycled Content and RPET Quality on the Properties of PET Bottles, Part II: Migration. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2020, 33, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Corredig, M.; Uysal Ünalan, I.; Tsochatzis, E. Untargeted Screening of NIAS and Cyclic Oligomers Migrating from Virgin and Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Food Trays. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 41, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, C.; Freire, M.T.D.A.; Nerín, C.; Bentayeb, K.; Rodriguez-Lafuente, A.; Aznar, M.; Reyes, F.G.R. Migration of Residual Nonvolatile and Inorganic Compounds from Recycled Post-Consumer PET and HDPE. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S. Pyrolysis and beyond: Sustainable Valorization of Plastic Waste. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 21, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Aguirre-Villegas, H.A.; Allen, R.D.; Bai, X.; Benson, C.H.; Beckham, G.T.; Bradshaw, S.L.; Brown, J.L.; Brown, R.C.; Cecon, V.S.; et al. Expanding Plastics Recycling Technologies: Chemical Aspects, Technology Status and Challenges. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 8899–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substance | Restriction or Specification |

|---|---|

| Terephthalic acid | SML = 7.5 mg/kg (expressed as terephthalic acid) |

| Isophthalic acid | SML = 5 mg/kg (expressed as isophthalic acid) |

| Dimethyl isophthalate | SML = 0.05 mg/kg |

| Mono- and diethylene glycol | SML = 30 mg/kg |

| Acetaldehyde | SML = 6 mg/kg |

| Food Classification |

|---|

| Non-acidic aqueous foods (pH > 4.5) |

| Acidic aqueous foods (pH < 4.5) |

| Fatty foods (containing fat or oils among their components |

| Alcoholic foods (alcohol content greater than 5% (v/v)) Dry food |

| Food Classification | Food Simulant |

|---|---|

| Only non-acidic aqueous foods | A |

| Only acidic aqueous foods | B |

| Only alcoholic foods | C |

| Only fatty foods | D or D’ |

| Non-acidic and alcoholic aqueous foods | C |

| Acidic and alcoholic aqueous foods | B and C |

| Non-acidic aqueous foods containing fats and oils | A and D or D’ |

| Acidic aqueous foods containing fats and oils | B and D or D’ |

| Non-acidic, alcoholic and fatty aqueous foods | C and D or D’ |

| Acidic, alcoholic and fatty aqueous foods | B, C and D or D’ |

| Non-fatty dry foods | No migration test required |

| Fatty dry foods | D or D’ |

| Characteristic | Substance |

|---|---|

| Volatile and polar | Chloroform Chlorobenzene 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Diethyl ketone |

| Volatile and non-polar | Toluene |

| Heavy metal | Copper (II) 2-ethyl hexanoate |

| Non-volatile and polar | Benzophenone Methyl salicylate |

| Non-volatile and non-polar | Tetracosane Lindane Methyl stearate Phenyl cyclohexane 1-Phenyldecane 2,4,6-Trichloroanisole |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcelino, C.S.; Gomes, V.E.d.S.; Marangoni Júnior, L. Post-Consumer Recycled PET: A Comprehensive Review of Food and Beverage Packaging Safety in Brazil. Polymers 2025, 17, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17050594

Marcelino CS, Gomes VEdS, Marangoni Júnior L. Post-Consumer Recycled PET: A Comprehensive Review of Food and Beverage Packaging Safety in Brazil. Polymers. 2025; 17(5):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17050594

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcelino, Carolina Soares, Vitor Emanuel de Souza Gomes, and Luís Marangoni Júnior. 2025. "Post-Consumer Recycled PET: A Comprehensive Review of Food and Beverage Packaging Safety in Brazil" Polymers 17, no. 5: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17050594

APA StyleMarcelino, C. S., Gomes, V. E. d. S., & Marangoni Júnior, L. (2025). Post-Consumer Recycled PET: A Comprehensive Review of Food and Beverage Packaging Safety in Brazil. Polymers, 17(5), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17050594