Design Strategies for Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Derived Materials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Methyl-based Substituents | ||

MeOx 2-methyl-2-oxazoline |  (F3)MeOx 2-trifluoromethyl-2-oxazoline |  (MeS)MeOx 2-(methyl-thio)-methyl-2-oxazoline |

| Ethyl-based Substituents | ||

EtOx 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline |  (BuO)EtOx 2-(2′-butoxy)ethyl-2-oxazoline |  (Carb)EtOx 2-(carbazolyl)ethyl-2-oxazoline |

(F3/MeO/Ph)EtOx 2-(2′,2′,2′-trifluoro-1′-methoxy-1′-phenyl)ethyl-2-oxazoline |  Et≡PhOx(Bn) (S)-4-benzyl-2-(ethynyl-phenyl)-2-oxazoline |  (Gal-S)EtOx 2-[2-(2′′,3′′,4′′,6′′-tetra-hydroxyl-β-d-galactopyrano-sylthio)ethyl]-2-oxazoline |

(5OAc∙Gal-S)EtOx 2-[2-(2′′,3′′,4′′,6′′-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyrano-sylthio)ethyl]-2-oxazoline |  (SH)EtOx 2-2′-mercaptoethyl-2-oxazoline |  (SBz)EtOx 2-[2′-(4′′-methoxy-benzyl)thio]ethyl-2-oxazoline |

(Py)EtOx 2-(2′-N-pyrrolidonylethyl)-2-oxazoline | ||

| Propyl-based Substituents | ||

nPrOx 2-n-propyl-2-oxazoline |  cPrOx 2-cyclo-propyl-2-oxazoline |  iPrOx 2-iso-propyl-2-oxazoline |

iPr=Ox 2-iso-prop-2′-enyl-2-oxazoline |  (OH)iPrOx 2-(2′-hydroxy-iso-propyl)-2-oxazoline |  (OH)nPrOx 2-(3′-hydroxy-n-propyl)-2-oxazoline |

(OSiMe2tBu)iPrOx 2-[(tert-butyl-dimethyl-silyl-oxy)-1-methyl-ethyl]-2-oxazoline |  (ester)nPrOx 2-(2′-methoxycarbonyl-ethyl)-2-oxazoline |  (MeO-EO1)nPrOx 2-(3′-methoxymonoethylene-glycol)-n-propyl-2-oxazoline |

(MeO-EO3)nPrOx 2-(3′-methoxytriethylene-glycol)-n-propyl-2-oxazoline |  (DiOxal)nPrOx 2-[3-(1,3)-dioxolan-2-yl-n-propyl]-2-oxazoline |  (CHO)nPrOx 2-(4-oxobutyl)-2-oxazoline |

| Butyl-based Substituents | ||

iBuOx 2-iso-butyl-2-oxazoline |  nBuOx(Et) 2-n-butyl-4-ethyl-2-oxazoline |  nBu≡Ox 2-n-but-3′-inyl-2-oxazoline |

tBuOx 2-tert-2-butyl-2-oxazoline |  (Cl-Ph)cBuOx 2-[1′-(4′′-chlorophenyl)-cyclo-butyl]-2-oxazoline |  (imid2PdI2)nBuOx 2-(4′-Bis(1′′,3′′-dimethyl-imidazoline-2-ylidene)-palladium(II) diiodide)-2-butyl-2-oxazoline |

(COOH)nBuOx 5-(2-oxazoline-2-yl)-pentanoic acid | ||

| Pentyl-based Substituents | ||

nPeOx 2-n-pentyl-2-oxazoline |  nPe≡Ox 2-n-pent-4′-enyl-2-oxazoline |  (bipy)nPeOx 2-(5′-(4′′-methyl-[2,2′-bipyridin]-4-yl)-n-pentyl)-2-oxazoline |

(Et)nPeOx 2-1′-ethyl-n-pentyl-2-oxazoline |  (NH2)nPeOx 2-5′-amino-n-pentyl-2-oxazoline |  (NHBoc)nPeOx Boc-protected 2-5′-amino-n-pentyl-2-oxazoline |

(OH)nPeOx 2-5′-hydroxyl-n-pentyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Hexyl-based Substitutents | ||

nHxOx 2-n-hexyl-2-oxazoline |  (bipy)nHxOx 2-(6′-(4′′-methyl-[2,2'-bipyridin]-4-yl)-n-hexyl)-2-oxazoline |  (9F)nHxOx: 2-(1′H,1′H,2′H,2′H)-perfluoro-n-hexyl-2-oxazoline |

(imid2PdI2)nHxOx 2-(4′-bis(1′′,3′′-dimethyl-imidazoline-2-ylidene)-palladium(II) diiodide)-2-n-hexyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Heptyl-based Substitutents | ||

nHpOx 2-n-heptyl-2-oxazoline |  (bipy)nHpOx 2-(7′-(4′′-methyl-[2,2′-bipyridin]-4-yl)-n-heptyl)-2-oxazoline |  (Et)HpOx 2-(3′-ethyl-n-heptyl)-2-oxazoline |

(MeMe)nHp= =Ox 2′,6′-dimethylhepta-1′,5′-dienyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Octyl-based Substitutents | ||

nOctOx 2-n-octyl-2-oxazoline |  (bipy)nOctOx 2-(5′-(4′′-methyl-[2,2′-bipyridin]-4-yl)-n-octyl)-2-oxazoline |  (imid2PdI2)nOctOx 2-(4′-Bis(1′′,3′′-dimethyl-imidazoline-2-ylidene)-palladium(II) diiodide)-2-n-octyl-2-oxazoline |

| Nonyl-based Substitutents | ||

nNonOx 2-n-nonyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Decyl-based Substitutents | ||

nDecOx 2-n-decyl-2-oxazoline |  (Gal-S)nDecOx 2-[2-(2′′,3′′,4′′,6′′-tetra-hydroxyl-β-d-galacto-pyranosylthio) decenyl]-2-oxazoline |  (5OAc∙Gal-S)nDecOx 2-[2-(2′′,3′′,4′′,6′′-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galacto-pyranosylthio) decenyl]-2-oxazoline |

| Decyl-based Substitutents | ||

nDec=Ox 2-n-dec-9′-enyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Undecyl-based Substitutents | ||

nUndOx 2-n-undecyl-2-oxazoline | ||

| Phenyl-based Substitutents | ||

PhOx 2-phenyl-2-oxazoline |  (tBu)PhOx 2-4′-tert-butyl-2-phenyl-2-oxazoline |  (2F)PhOx 2-2′,6′-difluorphenyl-2-oxazoline |

(F3CS)PhOx 2-[4′-(trifluoromethyl)-thio]phenyl-2-oxazoline |  (2I)PhOx(Bz) (S)-2-(3′,5′-diiodophenyl)-4-benzyl-2-oxazoline |  (2I)PhOx(Ph) (S)-2-(3′,5′-diiodophenyl)-4-phenyl-2-oxazoline |

(NH2)PhOx 2-4′-aminophenyl-2-oxazoline |  1,3-PhOxOx 2,2′-(1,3-phenylene)-bis(2-oxazoline) |  1,4-PhOxOx 2,2′-(1,4-phenylene)-bis(2-oxazoline) |

PhOx(iPr) (S)-4-iso-propyl-2-phenyl-2-oxazoline |  PhOx(Et) (R)-4-ethyl-2-phenyl-2-oxazoline |  PhOx(Ph) (R)-2,4-diphenyl-2-oxazoline |

(OH)PhOx o/m/p-(2-oxazoline-2-yl)-phenol |  (OBn)2PhOx 2-(3,5-bis(benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-oxazoline |  (thiophen)PhOx(Et) (R)-4-ethyl-2-(4-(thiophen-3-yl)phenyl)-2-oxazoline |

| Benzyl-based Substitutents | ||

BzOx 2-benzyl-2-oxazoline |  (CF3)BzOx 2-(4′-trifluoromethyl)benzyl-2-oxazoline | |

| Others | ||

FurOx 2-furan-2′-yl-2-oxazoline |  Soy= =Ox 2-heptadeca-9,13-dien-1-yl-2-oxazoline |  2,6-PyOxOx 2,2′-(2,6-pyridylene)-bis(2-oxazoline) |

OxOx 2,2′-bis-2-oxazoline | ||

2. Initiators and Terminating Agents

2.1. Unconventional Initiators

2.1.1. Metal Cations as Initiators

2.1.2. Iodine-Based Initiators

2.1.3. Advanced Organic Initiators

2.2. Initiators and Terminating Agents with Targeted Properties

2.2.1. Functionalization of Poly(2-oxazoline)s with Tracers

2.2.2. Functionalization of Poly(2-oxazoline)s with Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic End-Groups

2.2.3. Telechelic Poly(2-oxazoline)s as Antimicrobially Active Compounds

2.2.4. Functionalization of Poly(2-oxazoline)s with Non-Olefinic Reactive End-Groups

2.2.5. Functionalization of Poly(2-oxazoline)s with End-Groups Containing Unsaturated C–C Bonds

2.2.6. Telechelic Poly(2-oxazoline)s for Biological Applications

2.3. Macroinitiators for the Synthesis of Linear (co-) Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Usage of End-Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s as Macroinitiators

2.3.1. Poly(2-oxazoline)-co-poly(ε-caprolactone)s

2.3.2. Poly(2-oxazoline)-co-poly(lactid)s

2.3.3. Copoly(2-oxazoline)-co-poly(amino acid)s

2.3.4. Other Copolymers Containing Blocks of Copoly(2-oxazoline)s

2.3.5. Covalent Attachment to/Supramolecular Assembly with Cyclodextrins and other Cavitands

2.3.6. Combination of CROP and Controlled-Radical Polymerizations

2.4. Grafting of Brush- and Comblike Structures

2.4.1. Grafting from Pending 2-oxazoline Units

2.4.2. Grafting from Surfaces

2.4.3. Grafting from Heteropolymer Side-Chains

2.4.4. Grafting-onto Polymers

2.4.5. Grafting onto Surfaces

2.5. Star-Shaped Polymers Obtained from Using Macroinitiators

2.5.1. Multifunctional Tosylate and Triflate Initiators

2.5.2. Star-Shaped Poly(2-oxazoline) Structures Comprising Cyclodextrins

2.5.3. Further Multifunctional Initiators

2.5.4. Hyperstar Polymers and Second Generation Star Geometries

3. Synthesis of Poly(2-oxazoline)-Based Homo- and Copolymers

3.1. Homopoly(2-oxazoline)s and Homopolymers with Pending 2-Oxazoline Groups

3.1.1. Unconventional Solvents for the Performance of the CROP of 2-oxazolines

3.1.2. Synthesis of Monomers and the Corresponding Poly(2-oxazoline)s

3.1.3. LCST, UCST, and Glass-Transition Temperature of Homo Poly(2-oxazoline)s in Solution

3.1.4. Optical Rotation of Polymers with Pending 2-Oxazolinyl Substituents

3.1.5. Optical Rotation of Poly(2-oxazoline)s

3.2. Block Copoly(2-oxazoline)s

3.2.1. Block Copoly(2-oxazoline)s Containing a Block of pPhOx

3.2.2. Self-Assembly of Diblock Copoly(2-oxazoline)s

3.2.3. Self-Assembly of Triblock Copoly(2-oxazoline)s

4. Polymeranalogous Reactions

4.1. Polymeranalogous Reactions of poly(2-oxazoline)s Excluding (Partial) Hydrolysis

4.1.1. Click-Reactions Involving Olefinic Moieties

4.1.2. Click-Reactions Involving Alkines

4.1.3. Functional Groups with Protonable Functionalities/Acidic Protons in the Side-Chains

4.1.4. Various Polymeranalogous Reactions

4.2. Polymeranalogous Reactions Preceded by (Partial) Hydrolysis

4.2.1. Toxicity Studies of Poly(2-oxazoline)s and pEIs

4.2.2. Partial Hydrolysis: Copolymers Containing Units of pEI

4.2.3. Fully Hydrolyzed Poly(2-oxazoline)s

4.2.4. Antimicrobial Activity of (Partially) Hydrolyzed Poly(2-oxazoline)s

5. Conclusions

- The synthesis and polymerization of a large number of 2-oxazoline monomers has been reported during the last decade, enabling for the straight-forward synthesis of homo- and copoly(2-oxazoline)s with tailor made properties.

- Non-conjugated double bonds in the side-chains of poly(2-oxazoline)s do not need to be protected during the polymerization; alcohols, amines, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids in the poly(2-oxazoline) side-chains nonetheless need to be protected during the polymerization in order not to lose control of the polymerization and/or observe crosslinking of the polymer chains.

- Polymeranalogous click-reactions such as the thiol-ene reaction and the Huisgen cycloaddition further expand the range of functionalized poly(2-oxazoline)s.

- Despite the large number of 2-oxazoline monomers known, MeOx and EtOx are still in the main focus of investigations due to their water solubility and FDA approval; unambiguously, poly(2-oxazoline)s are considered as novel high-potential polymers for biomedic(in)al applications.

- In particular the choice and employment of dedicated functionalized initiators and terminating agents has been investigated recently, opening the pathway for semitelechelic and telechelic poly(2-oxazoline)s that have been successfully used as macroinitiators.

- The hydrolysis of poly(2-oxazoline)s, yielding pEI and pEI-stat-poly(2-oxazoline) random copolymers, is currently under thorough investigation, aimed at the development of novel carrier materials for biological applications.

- Telechelic poly(2-oxazoline)s and (partially) hydrolyzed poly(2-oxazoline)s display antimicrobial activity.

- Due to the control, the so-called livingness or at least quasi-livingness, of the CROP of poly(2-oxazoline)s, also complex polymer structures and architectures such as dendrimers, combs, brushes, star-shape and hyperbranched designs can be synthesized.

- The solubility and “solution behavior” of 2-oxazoline-based polymers and copolymers can be fine-tuned over a broad range, implying the formation of aggregates and their architecture (with relevance to biological applications) and paving the way to (micellar) catalysis with immobilized catalysts.

- Benefiting from the straight-forward and highly-effective synthesis of tailor-made poly(2-oxazoline)s and (co-)poly(ethylene imine)s, these classes of polymers are about to establish themselves as “common” polymers for advanced/biological applications, with high relevance as well as in the areas of complexation and supramolecular assemblies.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Tomalia, D.A.; Sheetz, D.P. Homopolymerization of 2-alkyl- and 2-aryl-2-oxazolines. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 1966, 4, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, W.; Aufderhaar, E.; Diepers, W.; Feinauer, R.; Nehring, R.; Thier, W.; Hellmann, H. Recent syntheses and reactions of cyclic imidic esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1966, 5, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiya, T.; Narisawa, S.; Maeda, T.; Fukui, K. Ring-opening polymerisation of 2-substituted 2-oxazolines. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Lett. 1966, 4, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiri, T.G.; Levy, A.; Litt, M. Polymerization of cyclic imino ethers. I. Oxazolines. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Lett. 1967, 5, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, C.; Bodner, T.; Stelzer, F.; Wiesbrock, F. One decade of microwave-assisted polymerizations: Quo vadis? Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 254–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, T.; Ellmaier, L.; Schenk, V.; Albering, J.; Wiesbrock, F. Delocalized π-electrons in 2-oxazoline rings resulting in negatively charged nitrogen atoms: Revealing the selectivity during the initiation of cationic ring-opening polymerizations. Polym. Int 2011, 60, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, M.; Fischer, D.; Kissel, T. Recent advances in rational gene transfer vector design based on poly(ethylene imine) and its derivatives. J. Gene Med. 2005, 7, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, M.; Schubert, S.; Ochrimenko, S.; Fischer, D.; Schubert, U.S. Branched and linear poly(ethylene imine)-based conjugates: Synthetic modification, characterization, and application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4755–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thünemann, A.F. Polyelectrolyte-surfactant complexes (synthesis, structure, and material aspects). Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 1473–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.M.; Wiesbrock, F. Strategies for the synthesis of poly(2-oxazoline)-based hydrogels. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 1632–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Guillerm, B.; Monge, S.; Lapinte, V.; Robin, J.-J. How to modulate the chemical structure of polyoxazolines by appropriate functionalization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 1600–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Han, Y.; Schulz, A.; Tong, J.; He, Z.; Kabanov, A.V.; Jordan, R. Poly(2-oxazoline)s as polymer therapeutics. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 1613–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R. Poly(2-oxazoline)s: A polymer class with numerous potential applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7978–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Schlaad, H. Bioinspired poly(2-oxazoline)s. Polymers 2011, 3, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaad, H.; Diehl, C.; Gress, A.; Meyer, M.; Demirel, A.L.; Nur, Y.; Bertin, A. Poly(2-oxazoline)s as smart bioinspired polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S. Ethylenimine polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1990, 15, 751–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Uyama, H. Poly(alkylenimine) derivatives: A variety of possible applications. Polym. News 1991, 16, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Aoi, K.; Okada, M. Polymerization of oxazolines. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1996, 21, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Uyama, H. Polymerization of cyclic imino ethers: From its discovery to the present state of the art. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.; Schubert, U.S. Poly(2-oxazolines) in biological and biomedical application contexts. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 1504–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Schubert, U.S. Parallel kinetic investigation of 2-oxazoline polymerizations with different initiators as basis for designed copolymer synthesis. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 1830–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, M.-E.; Vougioukalakis, G.C.; Hadjichristidis, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Metallocene-mediated cationic ring-opening polymerization of 2-methyl- and 2-phenyl-oxazoline. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 2520–2527. [Google Scholar]

- Buzin, P.; Schwarz, G.; Kricheldorf, H.R. Cationic polymerizations of 2-alkyloxazolines catalyzed by bismuth salts. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 4777–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, R.M.; Becer, C.R.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Acetyl halide initiator screening for the cationic ring-opening polymerization of 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2008, 209, 794–800. [Google Scholar]

- Guillerm, B.; Monge, S.; Lapinte, V.; Robin, J.-J. Novel investigations on kinetics and polymerization mechanism of oxazolines initiated by iodine. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 5964–5970. [Google Scholar]

- Volet, G.; Amiel, C.; Auvray, L. Interfacial properties of a diblock amphiphilic copolymer: Poly(isobutylvinyl ether-b-2-methyl-2-oxazoline). Macromolecules 2003, 36, 3327–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaied, O.; Delaite, C.; Hurtrez, G.; Joubert, M.; Dumas, P. Oxazoline-terminated macromonomers by the alkylation of 2-methyl-2-oxazoline. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2005, 43, 2440–2447. [Google Scholar]

- Reif, M.; Jordan, R. α,ω-Functionalized poly(2-oxazoline)s bearing hydroxyl and amino functions. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2011, 212, 1815–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Becer, C.R.; Baumgaertel, A.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Preparation of methacrylate end-functionalized poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) macromonomers. Des. Monomers Polym. 2009, 12, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; McAlvin, J.E.; Fraser, C.L.; Thomas, E.L. Iron cluster and microstructure formation in metal-centered star block copolymers: Amphiphilic iron tris(bipyridine)-centered polyoxazolines. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, K.; Vollrath, A.; Schaefer, H.W.; Poehlmann, T.G.; Biskup, C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Hornig, S.; Schubert, U.S. Multifunctional poly(2-oxazoline) nanoparticles for biological applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 31, 1869–1873. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner, F.C.; Luxenhofer, R.; Blechert, B.; Jordan, R.; Essler, M. Synthesis, biodistribution and excretion of radiolabeled poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s. J. Contr. Rel. 2007, 119, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R.; Park, J.-Y.; Advincula, R.C.; Winnik, F.M. Temperature-dependent interfacial properties of hydrophobically end-modified poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline)s assemblies at the air/water interface and on solid substrates. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 340, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R.; Maltseva, E.; Thünemann, A.F.; Tanaka, F.; Winnik, F.M. Temperature response of self-assembled micelles of telechelic hydrophobically modified poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s in water. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, G.; Chanthavong, V.; Wintgens, V.; Amiel, C. Synthesis of monoalkyl end-capped poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) and its micelle formation in aqueous solution. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5190–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, G.; Deschamps, A.-C.L.; Amiel, C. Association of hydrophobically α,ω-end-capped poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) in water. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, G.; Amiel, C. Polyoxazoline adsorption on silica nanoparticles mediated by host-guest interactions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 91, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, G.; Auvray, L.; Amiel, C. Monoalkyl poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) micelles. A small-angle neutron scattering study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 13536–13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, D.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Q. Formation of the crystalline inclusion complex between γ-cyclodextrin and poly(N-acetylethylenimine). Polymer 2002, 43, 2625–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Hutter, N.; Jordan, R. Effect of end group polarity upon the lower critical solution temperature of poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline). Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008, 286, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, V.G.; Bonifácio, V.D.B.; Raje, V.P.; Casimiro, T.; Moutinho, G.; da Silva, C.L.; Pinho, M.G.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A. Oxazoline-based antimicrobial oligomers: Synthesis by CROP using supercritical CO2. Macromol. Biosci. 2011, 11, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschinski, C.J.; Tiller, J.C. Poly(oxazoline)s with telechelic antimicrobial functions. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschinski, C.J.; Barnert, S.; Theobald, A.; Schubert, R.; Kleinschmidt, F.; Hoffmann, A.; Saalwächter, K.; Tiller, J.C. Insights in the antibacterial action of poly(methyloxazoline)s with a biocidal end group and varying satellite groups. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar]

- Waschinski, C.J.; Herdes, V.; Schueler, F.; Tiller, J.C. Influence of satellite groups on telechelic antimicrobial functions of polyoxazolines. Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 5, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiper, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. New terpyridine macroligands as potential synthons for supramolecular assemblies. Eur. Polym. J. 2010, 46, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Fang, Z.; Pasut, G.; Veronese, F.M.; Viegas, T.X. Selective conjugation of poly(2-ethyl 2-oxazoline) to granulocyte colony stimulating factor. J. Contr. Rel. 2012, 159, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoshi, T.; Hiramitsu, S.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamoto, Y. Columnar stacks of star- and tadpole-shaped polyoxazolines having triphenylene moiety and their applications for synthesis of wire-assembled gold nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 3042–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissault, B.; Kichler, A.; Leborgne, C.; Jarroux, N.; Cheradame, H.; Guis, C. Amphiphilic poly[(propylene glycol)-block-(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)] copolymers for gene transfer in skeletal muscle. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoenescu, R.; Meier, W. Vesicles with asymmetric membranes from amphiphilic ABC triblock copolymers. Chem. Commun. 2002, 3016–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijten, M.W.M.; Haensch, C.; van Lankvelt, B.M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Clickable poly(2-oxazoline)s as versatile building blocks. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2008, 209, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haensch, C.; Erdmenger, T.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Hoeppener, S.; Schubert, U.S. Fast surface modification by microwave assisted click reactions on silicon substrates. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8019–8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerca, V.V.; Nicolescu, F.A.; Vasilescu, D.S.; Albu, A.M.; Vuluga, D.M. Synthesis and structure of 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline macromonomers with styryl end-groups. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. B 2009, 71, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Volet, G.; Lav, T.-X.; Babinot, J.; Amiel, C. Click-chemistry: An alternative way to functionalize poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2011, 212, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemseghed, M.G.; Servello, J.; Hundt, N.; Sista, P.; Biewer, M.C.; Stefan, M.C. Amphiphilic block copolymers containing regioregular poly(3-hexylthiophene) and poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Glassner, M.; Kempe, K.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Barner-Kowollik, C. One-pot synthesis of cyclopentadienyl endcapped poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) and subsequent ambient temperature Diels-Alder conjugations. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10620–10622. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke, K.; Jordan, R.; Hommes, P.; Nuyken, O.; Naumann, C.A. Lipopolymers from new 2-substituted-2-oxazolines for artificial cell membrane constructs. Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 5, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Pasut, G.; Dalla Via, L.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Veronese, F.M. Synthesis and characterization of poly(2-ethyl 2-oxazoline)-conjugates with proteins and drugs: Suitable alternatives to PEG-conjugates? J. Contr. Rel. 2008, 125, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Luxenhofer, R.; Yi, X.; Jordan, R.; Kabanov, A.V. Protein modification with amphiphilic block copoly(2-oxazoline)s as a new platform for enhanced cellular delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 984–992. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny, S.; Fik, C.P.; Averesch, N.J.H.; Tiller, J.C. Organosoluble enzyme conjugates with poly(2-oxazoline)s via pyromellitic acid dianhydride. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 159, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Caponi, P.F.; Qiu, X.-P.; Vilela, F.; Winnik, F.M.; Ulijn, R.V. Phosphatase/temperature responsive poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline). Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Chiang, P.-R.; Shen, C.-R.; Hong, W.-H.; Hsiue, G.-H. Extended release of bevacizumab by thermosensitive biodegradable and biocompatible hydrogel. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, T.; Karjalainen, T.; Malin, M.; Peräkorpi, K.; Tuominen, J.; Seppälä, J.; Järvinen, K. Drug release profiles from and degradation of a novel biodegradable polymer, 2,2-bis(2-oxazoline) linked poly(ε-caprolactone). Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 16, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen, M.; Malin, M.; Tarvainen, T.; Saarimäki, T.; Seppälä, J.; Järvinen, K. Effects of block length on the enzymatic degradation and erosion of oxazoline linked poly-ε-caprolactone. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 31, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen, T.; Malin, M.; Suutari, T.; Pöllänen, M.; Tuominen, J.; Seppälä, J.; Järvinen, K. Pancreatin enhanced erosion of and macromolecule release from 2,2-bis(2-oxazoline)-linked poly(ε-caprolactone). J. Contr. Rel. 2003, 86, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.C.; Kim, C.; Kwon, I.C.; Chung, H.; Jeong, S.Y. Polymeric micelles of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(ε-caprolactone) copolymer as a carrier for paclitaxel. J. Contr. Rel. 2003, 89, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, W.; Ma, S.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Y. Synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-poly(d,l-lactide)-poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2007, 7, 4149–4159. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen, T.; Karjalainen, T.; Malin, M.; Pohjolainen, S.; Tuominen, J.; Seppälä, J.; Järvinen, K. Degradation of and drug release from a novel 2,2′-bis(2-oxazoline) linked poly(lactic acid) polymer. J. Contr. Rel. 2002, 81, 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiue, G.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Lo, C.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Li, J.-P.; Yang, J.-L. Environmental-sensitive micelles based on poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-b-poly(l-lactide) diblock copolymer for application in drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 317, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Hsiue, G.-H. New amphiphilic poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)/poly(l-lactide) triblock copolymers. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Hsiue, G.-H. Polymeric micelles with a pH-responsive structure as intracellular drug carriers. J. Contr. Rel. 2005, 108, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Obeid, R.; Scholz, C. Synthesis and self-assembly of well-defined poly(amino acid) endcapped poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline). Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3797–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-W.; Lee, H.-F.; Huang, C.-F.; Huang, C.-J.; Chang, F.-C. Synthesis and self-assembly of helical polypeptide-random coil amphiphilic diblock copolymer. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 3108–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Schlaad, H. Poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline)-poly(l-glutamate) block copolymers through ammonium-mediated NCA polymerization. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 3967–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Winnik, F.M. Synthesis of diblock copolymers consisting of hyaluronan and poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline). Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2043–2046. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H.; Wang, W.T.; Hsiue, G.-H. Development of polyion complex micelles for encapsulating and delivering amphotericin B. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3352–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemechko, P.; Renard, E.; Volet, G.; Colin, C.S.; Guezennec, J.; Langlois, V. Functionalized oligoesters from poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate)s containing reactive end group for click chemistry: Application to novel copolymer synthesis with poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline). React. Funct. Polym. 2012, 72, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Celebi, O.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, Y.; McGrath, J.E.; Riffle, J.S. Synthesis and characterization of polyoxazoline-polysulfone triblock copolymers. Polymer 2011, 52, 4718–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacman, M.J.; Barron, K.A.; Theogarajan, L.S. Clickable amphiphilic triblock copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halacheva, S.; Price, G.J.; Garamus, V.M. Effects of temperature and polymer composition upon the aqueous solution properties of comblike linear poly(ethylene imine)/poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-based polymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 7394–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nèry, L.; Lefebvre, H.; Fradet, A. Chain extension of carboxy-terminated aliphatic polyamides and polyesters by arylene and pyridylene bisoxazolines. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2004, 205, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadermann, J.; Komber, H.; Erber, M.; Däbritz, F.; Ritter, H.; Voit, B. Diblock copolymer formation via self-assembly of cyclodextrin and adamantyl end-functionalized polymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Giles, M.D.; Liu, S.; Laurent, B.A.; Hoskins, J.N.; Cortez, M.A.; Sreerama, S.G.; Gibb, B.C.; Grayson, S.M. A versatile and modular approach to functionalisation of deep-cavity cavitands via ‘‘click’’ chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9036–9038. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.; Voit, B. Synthesis and characterization of well-defined block copolymers by combining controlled radical and cationic polymerization. Macromol. Symp. 2009, 275–276, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becer, C.R.; Paulus, R.M.; Höppener, S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Fustin, C.-A.; Gohy, J.-F.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-b-poly(styrene) copolymers via a dual initiator route combining cationic ring-opening polymerization and atom transfer radical polymerization. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5210–5215. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Krieg, A.; Paulus, R.M.; Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Becer, C.R.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Thermal properties of oligo(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) containing comb and graft copolymers and their aqueous solutions. Macromol. Symp. 2011, 308, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.; Weber, C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Becer, C.R.; Schubert, U.S. Block copolymers of poly(2-oxazoline)s and poly(meth)acrylates: A crossover between cationic ring-opening polymerization (CROP) and reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT). ACS Macro. Lett. 2012, 1, 776–779. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, L.; Volet, G.; Amiel, C. Well-defined polyoxazoline-based alkoxyamines as efficient macroinitiators in nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization of styrene. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 4785–4793. [Google Scholar]

- Jerca, V.V.; Nicolescu, F.A.; Vasilescu, D.S.; Vuluga, D.M. Synthesis of a new oxazoline macromonomer for dispersion polymerization. Polym. Bull. 2011, 66, 785–796. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.A.; Malins, E.L.; Becer, C.R. Investigations on the combination of cationic ring opening polymerization and single electron transfer living radical polymerization to synthesize 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline block copolymers. Aust. J. Chem. 2012, 65, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.; Böhme, L.M.; Schmidt-Naake, G. Modification of polyacrylonitrile particles and grafted films with oxazolines. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2005, 206, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.; Schmidt-Naake, G. Cationic grafting of oxazolyl copolymers with 2-methyl and 2-phenyl oxazoline. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2004, 205, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Luxenhofer, R.; Jordan, R. Thermoresponsive poly(2-oxazoline) molecular brushes by living ionic polymerization: Kinetic investigations of pendant chain grafting and cloud point modulation by backbone and side chain length variation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2012, 213, 973–981. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Huber, S.; Schulz, A.; Luxenhofer, R.; Jordan, R. Cylindrical molecular brushes of poly(2-oxazoline)s from 2-isopropenyl-2-oxazoline. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 2215–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-H.; Yang, B.-X.; Goh, S.H. Covalent functionalization of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) by reactive melt blending. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerca, V.V.; Nicolescu, F.A.; Baran, A.; Anghel, D.F.; Vasilescu, D.S.; Vuluga, D.M. Synthesis and characterization of side-chain oxazoline-methyl methacrylate copolymers bearing azo-dye. React. Funct. Polym. 2010, 70, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Neuwirth, T.; Kempe, K.; Ozkahraman, B.; Tamahkar, E.; Mert, H.; Becer, C.R.; Schubert, U.S. 2-Isopropenyl-2-oxazoline: A versatile monomer for functionalization of polymers obtained via RAFT. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Steenachers, M.; Luxenhofer, R.; Jordan, R. Bottle-brush brushes: Cylindrical molecular brushes of poly(2-oxazoline) on glassy carbon. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 5345–5351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Pompe, T.; Amin, I.; Luxenhofer, R.; Werner, C.; Jordan, R. Tailored poly(2-oxazoline) polymer brushes to control protein adsorption and cell adhesion. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 926–936. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, N.A.; Reitinger, A.; Zhang, N.; Steenackers, M.; Williams, O.A.; Garrido, J.A.; Jordan, R. Microstructured poly(2-oxazoline) bottle-brush brushes on nanocrystalline diamond. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 4360–4366. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-H.; An, Y.-C.; Choi, D.-S.; Lee, M.-J.; Kim, K.-M.; Lim, J.-H. Fabrication of a nano-porous polyoxazoline-coated tip for scanning probe nanolithography. Macromol. Symp. 2007, 249–250, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz, B.; Gunes, D.; Bicak, N. Preparation of crosslinked poly(2-bromoethyl methacrylate) microspheres and decoration of their surfaces with functional polymer brushes. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; ten Brummelhuis, N.; Junginger, M.; Xie, Z.; Lu, Y.; Taubert, A.; Schlaad, H. Diversified applications of chemically modified 1,2-polybutadiene. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, J.C.; Zschoche, S.; Komber, H.; Krahl, F.; Arndt, K.-F.; Voit, B. New thermo-sensitive graft copolymers based on a poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) backbone and functional polyoxazoline grafts with random and diblock structure. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 706–716. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, J.; Zschoche, S.; Komber, H.; Schmaljohann, D.; Voit, B. Synthesis and characterization of thermoresponsive graft copolymers of NIPAAm and 2-alkyl-2-oxazolines by the “grafting from” method. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7330–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschoche, S.; Rueda, J.C.; Binner, M.; Komber, H.; Janke, A.; Arndt, K.-F.; Lehmann, S.; Voit, B. Reversibly switchable pH- and thermoresponsive core-shell nanogels based on poly(NiPAAm)-graft-poly(2-carboxyethyl-2-oxazoline)s. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2012, 213, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zschoche, S.; Rueda, J.; Boyko, V.; Krahl, F.; Arndt, K.-F.; Voit, B. Thermo-responsive nanogels based on poly[NIPAAm-graft-(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)]s crosslinked in the micellar state. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2011, 211, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Guillerm, B.; Darcos, V.; Lapinte, V.; Monge, S.; Coudane, J.; Robin, J.-J. Synthesis and evaluation of triazole-linked poly(ε-caprolactone)-graft-poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) copolymers as potential drug carriers. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2879–2881. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Becer, C.R.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Lower critical solution temperature behavior of comb and graft shaped poly[oligo(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)methacrylate]s. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 2965–2971. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Becer, C.R.; Guenther, W.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Dual responsive methacrylic acid and oligo(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) containing graft copolymers. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Konradi, R.; Pidhatika, B.; Mühlebach, A.; Textor, M. Poly-2-methyl-2-oxazoline: A peptide-like polymer for protein-repellent surfaces. Langmuir 2008, 24, 613–616. [Google Scholar]

- Poe, G.D.; McCormick, C.L. Synthesis, complex formation, and dilute-solution associative behavior of linear poly(methacrylic acid)-graft-poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline). J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 2520–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zheng, S. Poly(ethylene imine)-graft-poly(ethylene oxide) brush-like copolymers: Preparation, thermal properties, and selective supramolecular inclusion complexation with α-cyclodextrin. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2008, 46, 2296–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidhatika, B.; Möller, J.; Benetti, E.M.; Konradi, R.; Rakhmatullina, E.; Mühlebach, A.; Zimmermann, R.; Werner, C.; Vogel, V.; Textor, M. The role of the interplay between polymer architecture and bacterial surface properties on the microbial adhesion to polyoxazoline-based ultrathin films. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 9462–9472. [Google Scholar]

- Pidhatika, B.; Rodenstein, M.; Chen, Y.; Rakhmatullina, E.; Mühlebach, A.; Acikgöz, C.; Textor, M.; Konradi, R. Comparative stability studies of poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) and poly(ethylene glycol) brush coatings. Biointerphases 2012, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, M.; Rueda, J.C.; Uhlmann, P.; Müller, M.; Simon, F.; Stamm, M. Facile approach to grafting of poly(2-oxazoline) brushes on macroscopic surfaces and applications thereof. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeldt, F.; Tanaka, M.; Pagnoni, L.; Jordan, R. Static and dynamic swelling of grafted poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s. Langmuir 2002, 18, 4908–4914. [Google Scholar]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Bezen, M.; Jordan, R. Kinetic investigations on the polymerization of 2-oxazolines using pluritriflate initiators. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Kickelbick, G.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and crystal structures of multifunctional tosylates as basis for star-shaped poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)s. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, 773–783. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczuk, A.; Kronek, J.; Bosowska, K.; Trzebicka, B.; Dworak, A. Star poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)s-synthesis and thermosensitivity. Polym. Int. 2011, 60, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Adeli, M.; Kalantari, M.; Zarnega, Z.; Kabiri, R. Cyclodextrin-based dendritic supramolecules; new multivalent nanocarriers. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 2756–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, M.; Zarnegar, Z. Linear-dendritic copolymers as nanocatalysts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Adeli, M.; Zarnegar, Z.; Kabiri, R. Amphiphilic star copolymers containing cyclodextrin core and their application as nanocarrier. Eur. Polym. J. 2008, 44, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, M.; Schubert, U.S. Terpyridines as supramolecular initiators for living polymerization methods. Macromol. Symp. 2002, 177, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, G.L.; Edwards, J.M.; Payne, S.J.; Klinkenberg, J.L.; Gioeli, D.G.; Demas, J.N.; Fraser, C.L. Ruthenium(II) tris(bipyridine)-centered poly(ethylenimine) for gene delivery. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2829–2835. [Google Scholar]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Star-shaped poly(2-oxazoline)s by dendrimer endcapping. Aust. J. Chem. 2011, 64, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Jeerupan, J.; Ogoshi, T.; Hiramitsu, S.; Umeda, K.; Nemoto, T.; Konishi, G.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamoto, Y. Star-shaped poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) using by reactive bromoethyl group modified calix[4]resorcinarene as a macrocyclic initiator. Polym. Bull. 2008, 59, 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, R.; Yin, J. Amphipathic hyperbranched polymeric thioxanthone photoinitiators (AHPTXs): Synthesis, characterization and photoinitiated polymerization. Polymer 2009, 50, 3917–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausnitzer, C.; Voit, B.; Komber, H.; Voigt, D. Poly(ether amide) dendrimers via nucleophilic ring-opening addition reactions of phenol groups toward oxazolines: Synthesis and characterization. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 7065–7074. [Google Scholar]

- Däbritz, F.; Lederer, A.; Komber, H.; Voit, B. Synthesis and characterization of two classes of hyperstar polymers bearing hyperbranched cores grafted with linear arms. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Sanchez, C.; Lobert, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Microwave-assisted homogeneous polymerizations in water-soluble ionic liquids: An alternative and green approach for polymer synthesis. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2007, 28, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Macedo, C.V.; da Silva, M.S.; Casimiro, T.; Cabrita, E.J.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A. Boron trifluoride catalyzed polymerisation of 2-substituted-2-oxazolines in supercritical carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 948–953. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Lobert, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Screening the synthesis of 2-substituted-2-oxazolines. J. Comb. Chem. 2009, 11, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Lobert, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and characterization of a series of diverse poly(2-oxazoline)s. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 3829–3838. [Google Scholar]

- Rettler, E.F.-J.; Kranenburg, J.M.; Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Thermal, mechanical, and surface properties of poly(2-N-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2012, 211, 2443–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; van Kuringen, H.P.C.; van der Put, J.P.W.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Temperature induced solubility transitions of various poly(2-oxazoline)s in ethanol-water solvent mixtures. Polymers 2010, 2, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortez, M.A.; Grayson, S.M. Thiol-ene click functionalization and subsequent polymerization of 2-oxazoline monomers. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4081–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasu, A.; Kojima, H. Synthesis and ring-opening polymerizations of novel S-glycooxazolines. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 5953–5960. [Google Scholar]

- Diab, C.; Akiyama, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Winnik, F.M. Microcalorimetric study of the temperature-induced phase separation in aqueous solutions of poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazolines). Macromolecules 2004, 37, 2556–2562. [Google Scholar]

- Katsumoto, V.; Tsuchiizu, A.; Qiu, X.-P.; Winnik, F.M. Dissecting the mechanism of the heat-induced phase separation and crystallization of poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline) in water through vibrational spectroscopy and molecular orbital calculations. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 3531–3541. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel, A.L.; Meyer, M.; Schlaad, H. Formation of polyamide nanofibers by directional crystallization in aqueous solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8622–8624. [Google Scholar]

- Bloksma, M.M.; Weber, C.; Perevyazko, I.Y.; Kuse, A.; Baumgärtel, A.; Vollrath, A.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Poly(2-cyclopropyl-2-oxazoline): From rate acceleration by cyclopropyl to thermoresponsive properties. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 4057–4064. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Jacobs, S.; Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Fijten, M.M.W.M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Rational design of an amorphous poly(2-oxazoline) with a low glass-transition temperature: Monomer synthesis, copolymerization, and properties. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4098–4104. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, C.; Dambowsky, I.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schlaad, H. Self-assembly of poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s by crystallization in ethanol-water mixtures below the upper critical solution temperature. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 1753–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Thijs, H.M.L.; Jochems, M.J.H.C.; van Lankvelt, B.M.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Schubert, U.S. Tuning the LCST of poly(2-oxazoline)s by varying composition and molecular weight: Alternatives to poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)? Chem. Commun. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, M.; Filippov, S.K.; Panek, J.; Novakova, M.; Mackova, H.; Kucka, J.; Vetvicka, D.; Ulbrich, K. Polyoxazoline thermoresponsive micelles as radionuclide delivery systems. Macromol. Biosci. 2010, 10, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Pánek, J.; Filippov, S.K.; Hrubý, M.; Rabyk, M.; Bogomolova, A.; Kučka, J.; Štěpánek, P. Thermoresponsive nanoparticles based on poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s and pluronic F127. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Bloksma, M.M.; Bakker, D.J.; Weber, C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. The effect of Hofmeister salts on the LCST transition of poly(2-oxazoline)s with varying hydrophilicity. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 724–728. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanatraicharoen, P.; Shintaku, K.; Yamabuki, K.; Oishi, T.; Onimura, K. Synthesis and chiroptical properties of helical poly(phenylacetylene) bearing optically active chiral oxazoline pendants. Polymer 2012, 53, 2567–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanatraicharoen, P.; Yamabuki, K.; Oishi, T.; Onimura, K. Synthesis and characterization of optically active poly(phenylene-ethynylene)s containing chiral oxazoline derivatives. Polym. J. 2012, 44, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Xi, X.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Z. Optically active polymethacrylamides bearing a bulky oxazoline pendant: Synthesis and characterization. React. Funct. Polym. 2007, 67, 636–643. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, X.; Jiang, L.; Sun, W.; Shen, Z. Synthesis and anionic polymerization of optically active N-phenylmaleimides bearing bulky oxazoline substituents. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 2592–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, L.; Jiang, L.; Sun, W.; Shen, Z. A novel optically active diblock copolymer composed of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly[N-{o-(4-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1,3-oxazol-2-yl)phenyl}maleimide]: Synthesis, micellization behavior, and chiroptical property. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Yashima, E. Solvent-induced chiroptical changes in supramolecular assemblies of an optically active, regioregular polythiophene. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 4590–4601. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Yashima, E. Metal-induced supramolecular chirality in an optically active polythiophene aggregate. Chem. Eur. J. 2002, 8, 4027–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloksma, M.M.; Hendrix, M.M.R.M.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Ordered chiral structures in the crystals of main-chain chiral poly(2-oxazoline)s. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4654–4659. [Google Scholar]

- Bloksma, M.M.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Main-chain chiral copoly(2-oxazoline)s. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesbrock, F.; Hoogenboom, R.; Leenen, M.A.M.; Meier, M.A.R; Schubert, U.S. Investigation of the living cationic ring-opening polymerization of 2-methyl-, 2-ethyl-, 2-nonyl-, and 2-phenyl-2-oxazoline in a single-mode microwave reactor. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5025–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesbrock, F.; Hoogenboom, R.; Leenen, M.; van Nispen, S.F.G.M.; van der Loop, M.; Abeln, C.H.; van den Berg, A.M.J.; Schubert, U.S. Microwave assisted synthesis of a 4²-membered library of diblock copoly(2-oxazoline)s and chain-extended homo poly(2-oxazoline)s and their thermal characterization. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7957–7966. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Wiesbrock, F.; Huang, H.; Leenen, M.A.; Thijs, H.M.; van Nispen, S.F.; van der Loop, M.; Fustin, C.-A.; Jonas, A.M.; Gohy, J.-F.; Schubert, U.S. Microwave-assisted cationic ring-opening polymerization of 2-oxazolines: A powerful method for the synthesis of amphiphilic triblock copolymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 4719–4725. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesbrock, F.; Hoogenboom, R.; Leenen, M.A.; Thijs, H.M.; Huang, H.; Fustin, C.-A.; Guillet, P.; Gohy, J.-F.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and aqueous micellization of amphiphilic tetrablock copoly(2-oxazoline)s. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 2837–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Jochems, M.J.H.C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and properties of gradient copolymers based on 2-phenyl-2-oxazoline and 2-nonyl-2-oxazoline. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 6433–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Thijs, H.M.L.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Van Lankvelt, B.M.; Schubert, U.S. One-pot synthesis of 2-phenyl-2-oxazoline-containing quasi-diblock copoly(2-oxazoline)s under microwave irradiation. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg, J.M.; Thijs, H.M.L.; Tweedie, C.A.; Hoeppener, S.; Wiesbrock, F.; Hoogenboom, R.; Van Vliet, K.J.; Schubert, U.S. Correlating the mechanical and surface properties with the composition of triblock copoly(2-oxazoline)s. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fustin, C.-A.; Thijs-Lambermont, H.M.L.; Hoeppener, S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S.; Gohy, J.-F. Multiple micellar morphologies from tri- and tetrablock copoly(2-oxazoline)s in binary water-ethanol mixtures. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 3095–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebicka, B.; Koseva, N.; Mitova, V.; Dworak, A. Organization of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(2-phenyl-2-oxazoline) copolymers in water solution. Polymer 2010, 51, 2486–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustin, C.-A.; Lefèvre, N.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S.; Gohy, J.-F. Micellization of poly(2-oxazoline)-based quasi-diblock copolymers on surfaces. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2007, 208, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar]

- Kumm, C.; Fik, C.P.; Meuris, M.; Dropalla, G.J.; Geltenpoth, H.; Sickmann, A.; Tiller, J.C. Well-defined amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline) ABA-triblock copolymers and their aggregation behavior in aqueous solution. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, R.; Sato, T.; Terao, K.; Qiu, X.-P.; Winnik, F.M. Self-association of a thermosensitive poly(alkyl-2-oxazoline) block copolymer in aqueous solution. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 6111–6119. [Google Scholar]

- Casse, O.; Shkilnyy, A.; Linders, J.; Mayer, C.; Häussinger, D.; Völkel, A.; Thünemann, A.F.; Dimova, R.; Cölfen, H.; Meier, W.; et al. Solution behavior of double-hydrophilic block copolymers in dilute aqueous solution. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4772–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.T.T.; Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Kjoniksen, A.-L. Thermoresponsive poly(2-oxazoline) block copolymers exhibiting two cloud points: Complex multistep assembly behavior. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4337–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fustin, C.A.; Lefèvre, N.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S.; Gohy, J.-F. Surface micellization of poly(2-oxazoline)s based copolymers containing a crystallizable block. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 332, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, R.; Komenda, T.; Bonné, T.B.; Lüdtke, K.; Mortensen, K.; Pranzas, P.K.; Jordan, R.; Papadakis, C.M. Micellar structures of hydrophilic/lipophilic and hydrophilic/fluorophilic poly(2-oxazoline) diblock copolymers in water. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2008, 209, 2248–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotre, T.; Zarka, M.T.; Krause, J.O.; Buchmeiser, M.R.; Weberskirch, R.; Nuyken, O. Design and application of amphiphilic polymeric supports for micellar catalysis. Macromol. Symp. 2004, 217, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyken, O.; Persigehl, P.; Weberskirch, R. Amphiphilic poly(oxazoline)s–synthesis and application for micellar catalysis. Macromol. Symp. 2002, 177, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hoogenboom, R.; Leenen, M.A.M.; Guillet, P.; Jonas, A.M.; Schubert, U.S.; Gohy, J.-F. Solvent-induced morphological transition in core-cross-linked block copolymer micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar]

- Bonné, T.B.; Lüdtke, K.; Jordan, R.; Papadakis, C.M. Effect of polymer architecture of amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline) copolymers on the aggregation and aggregate structure. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2007, 208, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Sanchez, C.; Gohy, J.-F.; D’Haese, C.; Thijs, H.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Controlled thermoreversible transfer of poly(oxazoline) micelles between an ionic liquid and water. Chem. Commun. 2008, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Baumgaertel, A.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Design of new amphiphilic triblock copoly(2-oxazoline)s containing a fluorinated segment. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 5100–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Schulz, A.; Roques, C.; Li, S.; Bronich, T.K.; Batrakova, E.V.; Jordan, R.; Kabanov, A.V. Doubly amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline)s as high-capacity delivery system for hydrophobic drugs. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4972–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Brooks, E.; Montemagno, C.D. Synthesis and characterization of nanoscale biomimetic polymer vesicles and polymer membranes for bioelectronics applications. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfelder, D.; Fischer, K.; Schmidt, M.; Nuyken, O.; Weberskirch, R. Poly(2-oxazoline)s functionalized with palladium carbene complexes: Soluble, amphiphilic polymer supports for C–C coupling reactions in water. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; He, Z.; Schulz, A.; Bronich, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Luxenhofer, R.; Kabanov, A.V. Synergistic combinations of multiple chemotherapeutic agents in high capacity poly(2-oxazoline) micelles. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 2302–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. A green approach for the synthesis and thiol-ene modification of alkene functionalized poly(2-oxazoline)s. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, S.; Kurek, A.; Baur, M.A.; Auernheimer, J.; Nuyken, O. Polymer-bound thiol groups on poly(2-oxazoline)s. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2007, 28, 608–615. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Microwave-assisted cationic ring-opening polymerization of a soy-based 2-oxazoline monomer. Green Chem. 2006, 8, 895–899. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, K.; Neuwirth, T.; Czaplewska, J.; Gottschaldt, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Poly(2-oxazoline) glycopolymers with tunable LCST behavior. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar]

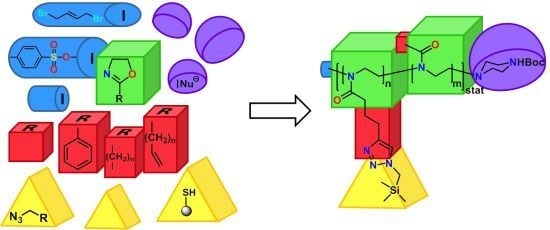

- Kempe, K.; Hoogenboom, R.; Jaeger, M.; Schubert, U.S. Three-fold metal-free efficient “click” reactions onto a multifunctional poly(2-oxazoline) designer scaffold. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 6424–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakisch, L.; Komber, H.; Böhme, F. Multifunctional coupling agents: Synthesis and model reactions. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2003, 41, 655–667. [Google Scholar]

- Gress, A.; Völkel, A.; Schlaad, H. Thio-click modification of poly[2-(3-butenyl)-2-oxazoline]. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 7928–7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, C.; Schlaad, H. Polyoxazoline-based crystalline microspheres for carbohydrate-protein recognition. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 11469–11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, E.; Lligadas, G.; Ronda, J.C.; Galià, M.; Cádiz, V. Poly-2-oxazoline-derived polyurethanes: A versatile synthetic approach to renewable polyurethane thermosets. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, C.; Schlaad, H. Thermo-responsive polyoxazolines with widely tuneable LCST. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, K.; Weber, C.; Babiuch, K.; Gottschaldt, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Responsive glycol-poly(2-oxazoline)s: Synthesis, cloud point tuning, and lectin binding. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2591–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Jordan, R. Click chemistry with poly(2-oxazoline)s. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 3509–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, N.; Schlaad, H. Stimuli-responsive star polymers through thiol-yne core functionalization/crosslinking of block copolymer micelles. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzenrieder, F.; Luxenhofer, R.; Retzlaff, M.; Jordan, R.; Finn, M.G. Stabilization of virus-like particles with poly(2-oxazoline)s. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2601–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, S.; Auernheimer, J.; Jordan, R.; Kessler, H.; Nuyken, O. First poly(2-oxazoline)s with pendant amino groups. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2006, 207, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronek, J.; Luston, J.; Kronekova, Z.; Paulovicova, E.; Farkas, P.; Petrencikova, N.; Paulovicova, L.; Janigova, I. Synthesis and bioimmunological efficiency of poly(2-oxazoline)s containing a free amino group. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010, 21, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubmann, C.; Luxenhofer, R.; Cesana, S.; Jordan, R. First aldehyde-functionalized poly(2-oxazoline)s for chemoselective ligands. Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 5, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luston, J.; Kronek, J.; Böhme, F. Synthesis and polymerization reactions of cyclic imino ethers. I. Ring-opening homopolyaddition of AB-type hydroxyphenyl-substituted 2-oxazolines. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.O.; Zarka, M.T.; Anders, U.; Weberskirch, R.; Nuyken, O.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Simple synthesis of poly(acetylene) latex particles in aqueous media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5965–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarka, M.T.; Nuyken, O.; Weberskirch, R. Polymer-bound, amphiphilic Hoveyda-Grubbs-type catalyst for ring-closing metathesis in water. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004, 25, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L.; Tong, Q.; Yan, M. Evaluation of photochemically immobilized poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) thin films as protein-resistant surfaces. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 3463–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Bonami, L.; Du Prez, F.E.; Hoogenboom, R. Linear poly(alkyl ethylene imne) with varying side chain length: Synthesis and physical properties. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Lautenschlaeger, C.; Kempe, K.; Tauhardt, L.; Schubert, U.S.; Fischer, D. Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) as alternative for the stealth polymer poly(ethylene glycol): Comparison of in vitro cytotoxicity and hemocompatibility. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Sahay, G.; Schulz, A.; Alakhova, D.; Bronich, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Kabanov, A.V. Structure-property relationship in cytotoxicity and cell uptake of poly(2-oxazoline) amphiphiles. J. Contr. Rel. 2011, 153, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kuringen, H.P.C.; Lenoir, J.; Adriaens, E.; Bender, J.; de Geest, B.G.; Hoogenboom, R. Partial hydrolysis of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) and potential implications for biomedical applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; van der Woerdt, F.S.; Baumgaertel, A.; Bonami, L.; Du Prez, F.E.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Linear poly(ethylene imine)s by acidic hydrolysis of poly(2-oxazoline)s: Kinetic screening, thermal properties, and temperature-induced solubility transitions. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niko, Y.; Konishi, G. Polymer-chain-induced tunable luminescence properties: Amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline)s possessing a N,N,-dialkylpyrene-1-carboxamide chromophore in the side chain. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2327–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiue, G.-H.; Chiang, H.-Z.; Wang, C.-H.; Juang, T.-M. Nonviral gene carriers based on diblock copolymers of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) and linear polyethylenimine. Bioconjug. Chem. 2006, 17, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lim, J.-H.; Kim, K.-M. Synthesis and characterization of novel hybrid polyoxazoline-grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 116, 2937–2943. [Google Scholar]

- Lambermont-Thijs, H.M.L.; Heuts, J.P.A.; Hoeppener, S.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Selective partial hydrolysis of amphiphilic copoly(2-oxazoline)s as basis for temperature and pH responsive micelles. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kuringen, H.P.C.; de la Rosa, V.R.; Fijten, M.W.M.; Heuts, J.P.A.; Hoogenboom, R. Enhanced selectivity for the hydrolysis of block copoly(2-oxazoline)s in ethanol-water resulting in linear poly(ethylene imine) copolymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Shkilnyy, A.; Tiersch, B.; Taubert, A.; Menzel, H. Preparation, characterization, and thermal gelation of amphiphilic alkyl-poly(ethyleneimine). Langmuir 2009, 25, 10558–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.M.B.; Johnson, M.A.; Boedicker, J.Q.; Hatton, T.A.; Hammond, P.T. Synthesis and bulk assembly behavior of linear-dendritic rod diblock copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 2784–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Ren, J. Covalent immobilization of ultrathin polymer films by thermal activation of perfluorophenyl azide. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhende, V.P.; Samanta, S.; Jones, D.M.; Hardin, I.R.; Locklin, J. One-step photochemical synthesis of permanent, nonleaching, ultrathin antimicrobial coatings for textiles and plastics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.-J.; Prucker, O.; Groh, E.; Wallrath, A.; Dahm, M.; Rühe, J. Surface-attached polymer monolayers for the control of endothelial cell adhesion. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002, 198–200, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, N.; Keul, H.; Heine, E.; Moeller, M. From multifunctionalized poly(ethylene imine)s toward antimicrobial coatings. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2874–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Kaltenhauser, V.; Mühlbacher, I.; Rametsteiner, K.; Kren, H.; Slugovc, C.; Stelzer, F.; Wiesbrock, F. Poly(2-oxazoline)-derived contact biocides: Contributions to the understanding of antimicrobial activity. Macromol. Biosci. 2013, 13, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Rossegger, E.; Schenk, V.; Wiesbrock, F. Design Strategies for Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Derived Materials. Polymers 2013, 5, 956-1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym5030956

Rossegger E, Schenk V, Wiesbrock F. Design Strategies for Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Derived Materials. Polymers. 2013; 5(3):956-1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym5030956

Chicago/Turabian StyleRossegger, Elisabeth, Verena Schenk, and Frank Wiesbrock. 2013. "Design Strategies for Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Derived Materials" Polymers 5, no. 3: 956-1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym5030956

APA StyleRossegger, E., Schenk, V., & Wiesbrock, F. (2013). Design Strategies for Functionalized Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Derived Materials. Polymers, 5(3), 956-1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym5030956