Integrated Weed Management in Herbaceous Field Crops

Abstract

:1. Introduction

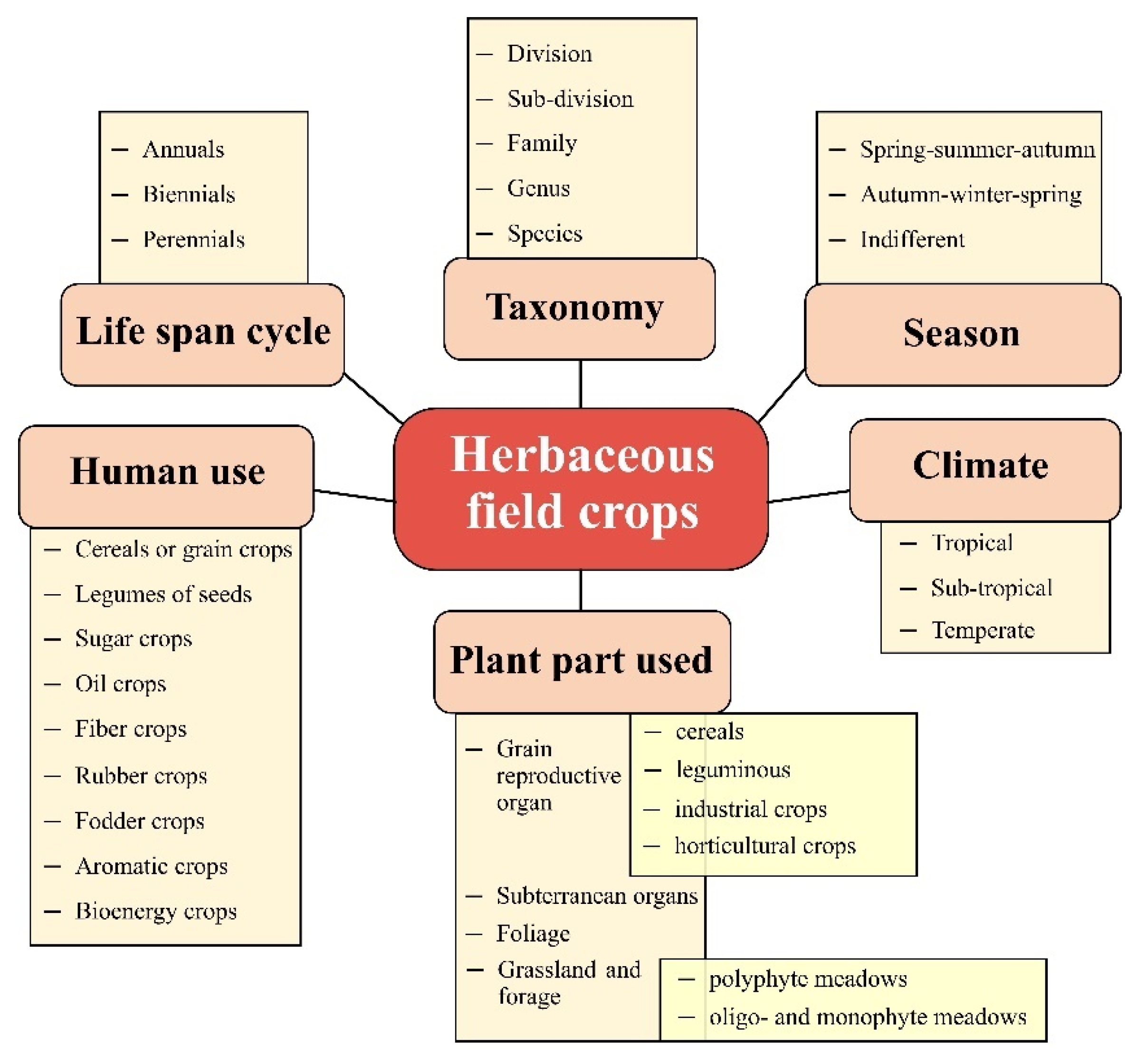

2. Weeds in Agroecosystems

- The ability to germinate under adverse environmental conditions.

- The ability to produce copious and diversified propagation organs, as well as the presence of mechanisms allowing to launch them at a distance and maintain long-viable seeds.

- The high production of seeds (e.g., more than 190,000 seeds plant−1 for Amaranthus retroflexus L. and Portulaca oleracea L.) and discontinuous germination.

- The rapid growth from the vegetative phase to flowering.

- The highly competitive capacity and allelopathic activity.

Harmful and Beneficial Effects of Weeds in Agroecosystems

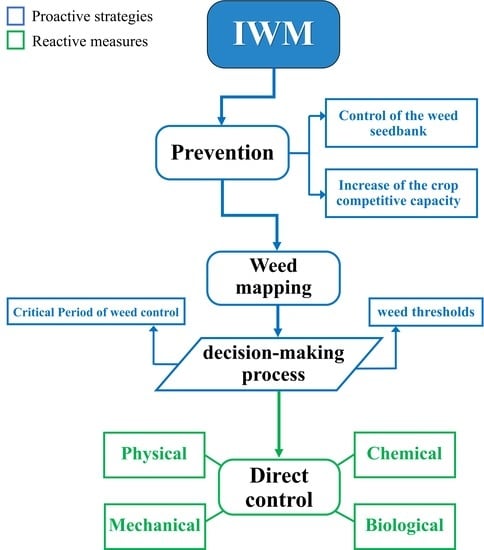

3. Development of an IWM Strategy

4. Preventive Methods

4.1. Control of the Soil Weed Seedbank

4.2. Increase of the Crop Competitive Capacity

5. The Decision-Making Process: from Weed Mapping to Weed Thresholds

6. Direct Methods

6.1. Mechanical Control

6.2. Physical Control

6.3. Biological Control

6.4. Chemical Control

7. Allelopathic Mechanisms for Weed Control

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oerke, E.-C.; Dehne, H.-W. Safeguarding production—Losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Prot. 2004, 23, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.-C. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, A.P.; Muller, F.; Carpy, S. Weed control. In Agrochemicals; Muller, F., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 687–707. [Google Scholar]

- Kraehmer, H.; Baur, P. Weed Anatomy; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Schärer, H.; Collins, A.R. Integrated Weed Management. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Management; Jorgensen, S.E., Ed.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhler, D.D.; Liebman, M.; Obrycki, J.J. Theoretical and practical challenges to an IPM approach to weed management. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Devos, Y.; Beckie, H.J.; Owen, M.D.K.; Tillie, P.; Messéan, A.; Kudsk, P. Integrated weed management systems with herbicide-tolerant crops in the European Union: Lessons learnt from home and abroad. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swanton, C.J.; Weise, S.F. Integrated weed management: The rationale and approach. Weed Technol. 1991, 5, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 21. Programme of Action for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- OJEU. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a fr amework for Community action to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 309, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic, S.Z. Integrated weed management in soybean. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Chauhan, B.S., Mahajan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwat, K.B.; Khan, M.A.; Hashim, S.; Nawab, K.; Khattak, A.M. Integrated weed management in wheat. Pak. J. Bot. 2011, 43, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Frederick, J.R. Integrated weed management strategies for maize (Zea mays) production on the southeastern coastal plains of North America. Crop Prot. 2005, 24, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Chauhan, B.S.; Kumar, V. Integrated weed management in rice. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Chauhan, B.S., Mahajan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, M.N.; Jabran, K.; Unay, A. Integrated weed management in cotton. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Chauhan, B.S., Mahajan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannacci, E.; Lattanzi, B.; Tei, F. Non-chemical weed management strategies in minor crops: A review. Crop Prot. 2017, 96, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.E. Integrated Weed Management in Horticultural Crops. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Chauhan, B.S., Mahajan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.G. Characteristics and modes of origin of weeds. In The Genetics of Colonizing Species; Baker, H.G., Stebbins, G.L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zimdahl, R.L. Fundamentals of Weed Science, 5th ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scavo, A.; Restuccia, A.; Mauromicale, G. Allelopathy: General principles and basic aspects for agroecosystem control. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Gaba, S., Smith, B., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 28, pp. 47–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, J.R.; Foy, C.L. Weed allelopathy, its ecological impacts and future prospects: A review. J. Crop. Prod. 2001, 4, 43–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.H. Allelopathy as a factor in ecological process. Vegetatio 1969, 18, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Abbate, C.; Mauromicale, G. Plant allelochemicals: Agronomic, nutritional and ecological relevance in the soil system. Plant Soil 2019, 442, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.; Ramakrishnan, P.S. Studies on crop-legume behaviour in pure and mixed stands. Agro-Ecosyst. 1975, 2, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, N.; Vatovec, C. Agroecological benefits from weeds. In Weed Biology and Management; Inderjit, Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitters, C.J.T.; Kropff, M.J.; de Groot, W. Competition between maize and Echinochloa crus-galli analysed by a hyperbolic regression model. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1989, 115, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cousens, R. A simple model relating yield loss to weed density. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1985, 107, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, J.T.; Remy, E.A.S.; O’Sullivan, P.A.; Dew, D.A.; Sharma, A.K. Influence of the relative time of emergence of wild oat (Avena fatua) on yield loss of barley (Hordeum vulgare) and wheat (Triticum aestivum). Weed Sci. 1985, 33, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousens, R.; Brain, P.; O’Donovan, J.T.; O’Sullivan, A. The use of biologically realistic equations to describe the effects of weed density and relative time of emergence on crop yield. Weed Sci. 1987, 35, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasieniuk, M.; Maxwell, B.D.; Anderson, R.L.; Evans, J.O.; Lyon, D.J.; Miller, S.D.; Don, W.; Morishita, D.W.; Ogg, A.G.; Seefeldt, S.S.; et al. Evaluation of models predicting winter wheat yield as a function of winter wheat and jointed goatgrass densities. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropff, M.J.; Spitters, C.J.T. A simple model of crop loss by weed competition from early observations on relative leaf area of the weeds. Weed Res. 1991, 31, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropff, M.J.; Lotz, L.A.P. Systems approaches to quantify crop-weed interactions and their application in weed management. Agric. Syst. 1992, 40, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, K.N.; O’Donovan, J.T. Recent weed control, weed management, and integrated weed management. Weed Technol. 2003, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsolus, J.L.; Buhler, D.D. A risk management perspective on integrated weed management. J. Crop. Prod. 1999, 2, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, S.Z.; Jhala, A.; Datta, A. Integrated weed management. In Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, 2nd ed.; Thomas, B., Murray, B.G., Murphy, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Harker, K.N.; O’Donovan, J.T.; Blackshaw, R.E.; Beckie, H.J.; Mallory-Smith, C.; Maxwell, B.D. Our view. Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zanin, G.; Ferrero, A.; Sattin, M. La gestione integrata delle malerbe: Un approccio sostenibile per il contenimento delle perdite di produzione e la salvaguardia dell’ambiente. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.; Grundy, A.C. Non-chemical weed management in organic farming systems. Weed Res. 2001, 41, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Restuccia, A.; Abbate, C.; Mauromicale, G. Seeming field allelopathic activity of Cynara cardunculus L. reduces the soil weed seed bank. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallandt, E.R. How can we target the weed seedbank? Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bàrberi, P. Weed management in organic agriculture: Are we addressing the right issues? Weed Res. 2002, 42, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardina, J.; Herms, C.P.; Doohan, D.J. Crop rotation and tillage systems effects on weed seedbanks. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, J.; Del Monte, J.P.; López-Fando, C. Weed seed bank response to crop rotation and tillage in semiarid agro-ecosystems. Weed Sci. 1999, 47, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauromicale, G.; Lo Monaco, A.; Longo, A.M.G.; Restuccia, A. Soil solarization, a nonchemical method to control branched broomrape (Orobanche ramosa) and improve the yield of greenhouse tomato. Weed Sci. 2005, 53, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Longo, A.M.G.; Lo Monaco, A.; Mauromicale, G. The effect of soil solarization and fumigation on pests and yields in greenhouse tomatoes. Crop Prot. 2012, 37, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, R.; Lo Monaco, A.; Lombardo, S.; Restuccia, A.; Mauromicale, G. Eradication of Orobanche/Phelipanche spp. seedbank by soil solarization and organic supplementation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauromicale, G.; Restuccia, G.; Marchese, M. Soil solarization, a non-chemical technique for controlling Orobanche crenata and improving yield of faba bean. Agronomie 2001, 21, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubin, B.; Benjamin, A. Solar heating of the soils: Involvement of environmental factors in the weed control process. Weed Sci. 1984, 32, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Regve, Y.; Herzlinger, G. Solarization for weed control. Weed Sci. 1983, 31, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, B.; Rasmussen, I.A.; Bàrberi, P. Integrating physical and cultural methods of weed control—Examples from European research. Weed Sci. 2005, 53, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauromicale, G.; Occhipinti, A.; Mauro, R.P. Selection of shade-adapted subterranean clover species for cover cropping in orchards. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauro, R.P.; Occhipinti, A.; Longo, A.M.G.; Mauromicale, G. Effects of shading on chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis of subterranean clover. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2011, 197, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, A.; Onofri, A.; Zanin, G.; Sattin, M. Sistema integrato di gestione della lotta alle malerbe (IWM). In Malerbologia; Catizone, P., Zanin, G., Eds.; Pàtron Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2001; pp. 659–710. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, J.R.; Mohler, C.L. The quantitative relationship between weed emergence and the physical properties of mulches. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemessa, F.; Wakjira, M. Mechanisms of ecological weed management by cover cropping: A review. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 14, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bàrberi, P.; Mazzoncini, M. Changes in weed community composition as influenced by cover crop and management system in continuous corn. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, O.A.; Zhou, X.M.; Cloutier, D.; Coulman, D.C.; Faris, M.A.; Smith, D.L. Cover crops and interrow tillage for weed control in short season maize (Zea mays). Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 12, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.R.; Stoltenberg, D.E.; Posner, J.L.; Hedtcke, J.L. Weed community dynamics and suppression in tilled and no-tillage transitional organic winter rye-soybean systems. Weed Sci. 2014, 62, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; McClelland, M.; Griffith, G.; Bangarwa, S.K.; Still, J. Evaluation of cereal and Brassicaceae cover crops in conservation-tillage, enhanced, glyphosate-resistant cotton. Weed Technol. 2011, 25, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, V.; Mahajan, G.; Jabran, K.; Chauhan, B.S. Role of competition in managing weeds: An introduction to the special issue. Crop Prot. 2017, 95, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E.; Froud-Williams, R.J. Effects of winter wheat cultivars and seed rate on the biological characteristics of naturally occurring weed flora. Weed Res. 2002, 42, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, B.P.; Cope, A.E.; Mortimer, M. Growth traits of diverse rice cultivars under severe competition: Implications for screening for competitiveness. Field Crops Res. 2003, 83, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, B.; Chauhan, B.S.; Thierfelder, C. Weed management in maize using crop competition: A review. Crop Prot. 2016, 88, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannink, J.L.; Orf, J.H.; Jordan, N.R.; Shaw, R.G. Index selection for weed suppressive ability in soybean. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, W.T.; Boykin, D.; Hugie, J.A.; Ratnayaka, H.H.; Sterling, T.M. Spurred anoda (Anoda cristata) interference in wide row and ultra narrow row cotton. Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.R.; Derksen, D.A.; Van Acker, R.C. The ability of 29 barley cultivars to compete and withstand competition. Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willey, R.W.; Heath, S.B. The quantitative relationship between plant population density and crop yield. Adv. Agron. 1969, 21, 281–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.A.; Reddy, K.N.; Zablotowicz, R.M. Weed management in conservation crop production systems. Weed Biol. Manag. 2002, 2, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnic, A.C.; Swanton, C.J. Influence of barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crusgalli) time of emergence and density on corn (Zea mays). Weed Sci. 1997, 45, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaans, L.; Paolini, R.; Baumann, D.T. Focus on ecological weed management: What is hindering adoption? Weed Res. 2008, 48, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, M.; Bastiaans, L.; Baumann, D.T. Weed management in low-external-input and organic farming systems. In Weed Biology and Management; Inderjit, Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müeller-Dombois, D.; Ellenberg, H. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Cristaudo, A.; Restuccia, A.; Onofri, A.; Lo Giudice, V.; Gresta, F. Species–area relationships and minimum area in citrus grove weed communities. Plant Biosyst. 2015, 149, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krähmer, H.; Andreasen, C.; Economou-Antonaka, G.; Holec, J.; Kalivas, D.; Kolářová, M.; Novák, R.; Panozzo, S.; Pinke, G.; Salonen, J.; et al. Weed surveys and weed mapping in Europe: State of the art and future tasks. Crop Prot. 2020, 129, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousens, R. Theory and reality of weed control thresholds. Plant Prot. Q. 1987, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton, C.J.; Weaver, S.; Cowan, P.; Van Acker, R.; Deen, W.; Shreshta, A. Weed thresholds: Theory and applicability. J. Crop. Prod. 1999, 2, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, S.Z.; Datta, A. The critical period for weed control: Revisiting data analysis. Weed Sci. 2015, 63, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, M.R.; Swanton, C.J.; Anderson, G.W. The critical period of weed control in grain corn (Zea mays). Weed Sci. 1992, 40, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Weide, R.Y.; Bleeker, P.O.; Achten, V.; Lotz, L.A.P.; Fogelberg, F.; Melander, B. Innovation in mechanical weed control in crop rows. Weed Res. 2008, 48, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, D.C.; Giles, D.K.; Downey, D. Autonomous robotic weed control systems: A review. Comp. Electron. Agric. 2008, 61, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.G.; Van Acker, R.C.; Friesen, L.F. Critical period of weed control in spring canola. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanton, C.J.; O’Sullivan, J.; Robinson, D.E. The critical weed-free period in carrot. Weed Sci. 2010, 58, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, G.; Javanshir, A.; Khooie, F.R.; Mohammadi, S.A.; Salmasi, S.Z. Critical period of weed interference in chickpea. Weed Res. 2005, 45, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukun, B. Critical periods for weed control in cotton in Turkey. Weed Res. 2004, 44, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursun, N.; Bukun, B.; Karacan, S.C.; Ngouajio, M.; Mennan, H. Critical period for weed control in leek (Allium porrum L.). Hortscience 2007, 42, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitchger, J.A.; Burke, I.C.; Yenish, J.P. The critical period of weed control in lentil (Lens culinaris) in the Pacific Northwest. Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everman, W.J.; Clewis, S.B.; Thomas, W.E.; Burke, I.C.; Wilcut, J.W. Critical period of weed interference in peanut. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadvand, G.; Mondani, F.; Golzardi, F. Effect of crop plant density on critical period of weed competition in potato. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 121, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursun, N.; Akinci, I.E.; Uludag, A.; Pamukoglu, Z.; Gozcu, D. Critical period for weed control in direct seeded red pepper (Capsicum annum L.). Weed Biol. Manag. 2012, 12, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, C.R.; Swanton, C.J.; Weise, S.F. The critical period of weed control in soybean [Glycine max. (L) Merr.]. Weed Sci. 1993, 41, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, S.Z.; Elezovic, I.; Datta, A.; Vrbnicanin, S.; Glamoclija, D.; Simic, M.; Malidza, G. Delay in the critical time for weed removal in imidazolinone-resistant sunflower (Helianthus annuus) caused by application of pre-emergence herbicide. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2013, 59, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.E.; Tan, C.S. Critical period of weed interference in transplanted tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum): Growth analysis. Weed Sci. 1983, 31, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, B.L.; Michaels, T.E.; Hall, M.R.; Swanton, C.J. The critical period of weed control in white bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Weed Sci. 1993, 41, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.P.; Bulson, H.A.J.; Stopes, C.E.; Froud-Williams, R.J.; Murdoch, A.J. The critical weed-free period in organically-grown winter wheat. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1999, 134, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, S.V. Weed management in conservation agriculture systems. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Chauhan, B.S., Mahajan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.R.; Alzugaray, C.; Torres, P.S.; Lewis, P. The effect of different tillage systems on the composition of the seedbank. Weed Res. 1997, 37, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, B.S.; Wilson, H.P.; Hines, T.E. Management programs and crop rotations influence populations of annual grass weeds and yellow nutsedge. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, M.T.; Verdú, A.M.C. Tillage system effects on weed communities in a 4-year crop rotation under Mediterranean dryland conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2003, 74, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rask, A.M.; Kristoffersen, P. A review of non-chemical weed control on hard surface. Weed Res. 2007, 47, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitsuyama, Y.; Ichikawa, S. Possible weed establishment control by applying cryogens to fields before snowfalls. Weed Technol. 2011, 25, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascard, J. Effects of flame weeding on weed species at different developmental stages. Weed Res. 1995, 35, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguë, C.; Gill, J.; Péloquin, G. Thermal control in plant protection. In Physical Control Methods in Plant Protection; Vincent, C., Panneton, B., Fleurat-Lessard, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, J.J.; Zandstra, B.H. Flame weeding effects on several weed species. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeau, S.; Triolet, M.; Wayman, S.; Steinberg, C.; Guillemin, J.P. Bioherbicides: Dead in the water? A review of the existing products for integrated weed management. Crop Prot. 2016, 87, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzländer, M.; Hinz, H.L.; Winston, R.L.; Day, M.D. Biological control of weeds: An analysis of introductions, rates of establishment and estimates of success, worldwide. BioControl 2018, 63, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charudattan, R. Biological control of weeds by means of plant pathogens: Significance for integrated weed management in modern agro-ecology. BioControl 2001, 46, 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.W.; Shaw, R.H.; Sforza, R. Top 20 environmental weeds for classical biological control in Europe: A review of opportunities, regulations and other barriers to adoption. Weed Res. 2006, 46, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.O.; Dayan, F.E.; Romagni, J.G.; Rimando, A.M. Natural products as sources of herbicides: Current status and future trends. Weed Res. 2000, 40, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, F.E.; Owens, D.K.; Duke, S.O. Rationale for a natural products approach to herbicide discovery. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejías, F.J.R.; Trasobares, S.; López-Haro, M.; Varela, R.M.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Calvino, J.J.; Macías, F.A. In situ eco encapsulation of bioactive agrochemicals within fully organic nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41925–41934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, B.; Rasmussen, G. Effects of cultural methods and physical weed control on intrarow weed numbers, manual weeding and marketable yield in direct-sown leek and bulb onion. Weed Res. 2001, 41, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanovic, S.; Datta, A.; Neilson, B.; Bruening, C.; Shapiro, C.A.; Gogos, G.; Knezevic, S.Z. Effectiveness of flame weeding and cultivation for weed control in organic maize. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2016, 32, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Mitschunas, N. Fungal effects on seed bank persistence and potential applications in weed biocontrol: A review. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2008, 9, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlert, K.A.; Mangold, J.M.; Engel, R.E. Integrating the herbicide imazapic and the fungal pathogen Pyrenophora semeniperda to control Bromus tectorum. Weed Res. 2014, 54, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannacci, E.; Tei, F. Effects of mechanical and chemical methods on weed control, weed seed rain and crop yield in maize, sunflower and soybean. Crop Prot. 2014, 64, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiadis, V.P.; Froud-Williams, R.J.; Eleftherohorinos, I.G. Tillage and herbicide treatments with inter-row cultivation influence weed densities and yield of three industrial crops. Weed Biol. Manag. 2012, 12, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, D. Herbicide action and metabolism. In Turf Weeds and Their Control; ASA, CSSA, Eds.; American Society of Agronomy and Crop Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, I. The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Available online: www.weedscience.org (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Christoffers, M.J.; Nandula, V.K.; Mengistu, L.W.; Messersmith, C.G. Altered herbicide target sites: Implications for herbicide-resistant weed management. In Weed Biology and Management; Inderjit, Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, M.; Duke, S.O.; Fedtke, C. Physiology of Herbicide Action; PTR: Prentice Hall, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- LeBaron, H.; Gressel, J. Herbicide Resistance in Plants; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, F.A.; Kirkland, K.J.; Stevenson, F.C. Defining optimum herbicide rates and timing for wild oat (Avena fatua) control in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum). Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Brain, P.; Marshall, E.J.P.; Caseley, J.C. Modelling herbicide dose and weed density effects on crop: Weed competition. Weed Res. 2002, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Abugho, S.B. Interaction of rice residue and PRE herbicides on emergence and biomass of four weed species. Weed Technol. 2012, 26, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, F.A.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Varela, R.M.; Galindo, J.C.G. Allelopathy—A natural alternative for weed control. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesio, F.; Ferrero, A. Allelopathy, a chance for sustainable weed management. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 2010, 17, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Jabran, K.; Cheema, Z.A.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K.H. The role of allelopathy in agricultural pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, M.M. Influence of tillage, crop rotation, and weed management on giant foxtail (Setaria faberi) population dynamics and corn yield. Weed Sci. 1992, 40, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalburtji, K.L.; Gagianas, A. Effects of sugar beet as a preceding crop on cotton. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 1997, 178, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadawi, I.S.; Sarbout, A.K.; Al-Shamma, L.M. Differential allelopathic potential of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) genotypes on weeds and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) crop. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2012, 58, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midya, A.; Bhattacharjee, K.; Ghose, S.S.; Banik, P. Deferred seeding of blackgram (Phaseolus mungo L.) in rice (Oryza sativa L.) field on yield advantages and smothering of weeds. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2005, 191, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, Z.A.; Khaliq, A.; Saeed, S. Weed control in maize (Zea mays L.) through sorghum allelopathy. J. Sustain. Agric. 2004, 23, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.A.; Tawaha, A.M. Allelopathic effect of black mustard (Brassica nigra L.) on germination and growth of wild oat (Avena fatua L.). Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A. Potential of a black walnut (Juglans nigra) extract product (NatureCur®) as a pre- and post-emergence bioherbicide. J. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 33, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabran, K.; Cheema, Z.A.; Farooq, M.; Hussain, M. Lower doses of pendimethalin mixed with allelopathic crop water extracts for weed management in canola (Brassica napus). Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Jabran, K.; Mahajan, G.; Sardana, V.; Chauhan, B.S. Allelopathy for weed control in agricultural systems. Crop Prot. 2015, 72, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruidhof, H.M.; Bastiaans, L.; Kropff, M.J. Cover crop residue management for optimizing weed control. Plant Soil 2009, 318, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Restuccia, A.; Pandino, G.; Onofri, A.; Mauromicale, G. Allelopathic effects of Cynara cardunculus L. leaf aqueous extracts on seed germination of some Mediterranean weed species. Ital. J. Agron. 2018, 13, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scavo, A.; Pandino, G.; Restuccia, A.; Lombardo, S.; Pesce, G.R.; Mauromicale, G. Allelopathic potential of leaf aqueous extracts from Cynara cardunculus L. on the seedling growth of two cosmopolitan weed species. Ital. J. Agron. 2019, 14, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scavo, A.; Pandino, G.; Restuccia, A.; Mauromicale, G. Leaf extracts of cultivated cardoon as potential bioherbicide. Sci. Hort. 2020, 261, 109024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Rial, C.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Varela, R.M.; Mauromicale, G.; Macias, F.A. The extraction procedure improves the allelopathic activity of cardoon (Cynara cardunculus var. altilis) leaf allelochemicals. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Rial, C.; Varela, R.M.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Mauromicale, G.; Macias, F.A. 2019 Influence of genotype and harvest time on the Cynara cardunculus L. sesquiterpene lactone profile. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 6487–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Data | Type of Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Empirical models | |||

| D = weed density i = yield loss per weed m−2 as D→ 0 | Rectangular hyperbola with one parameter | [26] | |

| A = maximum yield loss as D→ ∞ | Rectangular hyperbola with two parameters | [27] | |

| b0 = Y intercept b1 = regression coefficient for X1 X1 = time interval between weed and crop emergence b2 = regression coefficient for density X2 = weed density (plants m−2) | Linear through multiple-regression model | [28] | |

| T = time interval between weed and crop emergence C = nonlinear regression coefficient | Rectangular hyperbola with three parameters and sigmoidal relationship between C and T | [29] | |

| Dc = crop density Dw = weed density Ymax = maximum crop yield | Rectangular hyperbola consisting in two linked hyperbolic equations | [30] | |

| (B) Ecophysiological models | |||

| Lw = relative leaf area of the weed q = relative damage coefficient of the weed on the crop | Rectangular hyperbola with one parameter | [31] | |

| m = maximum yield loss caused by weeds | Rectangular hyperbola with two parameters | [32] |

| Action | Main Effect | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (A) Control of the soil weed seedbank | ||

| Crop rotation | Reduction in weed emergence and germination | The diversification of the crop sequence prevents weeds from adapting and establishing, thus disrupting the establishment of a specialized flora in favour of a multifaceted weed community composed by many species each present at low density. |

| Stale seedbed | Reduction in weed emergence | An earlier seedbed preparation combined with a light irrigation or rainfall and followed by a mechanical, physical or chemical weed control, limits weed emergence in early stages of the crop growing period. |

| Soil solarization | Reduction in weed germination | Solarization allows reaching 50–55 °C at 5 cm soil depth and more than 40 °C in the surface layers, thus preventing seed germination by thermal killing of germinating seeds or inducing seed dormancy. |

| Good agronomic practices | Reduction in seedbank input | Adoption of certified seeds with high pureness rate, cleaning equipment and mechanical tools before moving from field to field, avoid transportation of soil from weed-infested areas, use well-composted manure, filtering irrigation water, field sanification (including uncultivated areas) before weed reproduction. |

| Ploughing | Increase in seedbank output | Ploughing, by influencing the vertical distribution of the seedbank, on one side decreases the germination of buried weed seeds and, on the other side, increases predation and physiological death of weed seeds on the soil surface. |

| Cover cropping, mulching, intercropping and green manuring | Reduction in weed emergence | Living mulches between rows and buried or shallow dead mulches prevent weed germination physically and chemically through allelopathy. |

| (B) Increase of the crop competitive capacity | ||

| Choice of weed-competitive cultivars | Increase in speed soil cover rates in early stages | Choice of cultivars with high root development, early vigour, faster seedling emergence, high growth rates, wide leaf area and allelopathic ability. |

| Crop density | Reduction in weed emergence and biomass | The increase in crop density and the reduction of row spacing influence the weed-crop competition in favour of the crop. |

| Spatial patterns and plant arrangement | Improvement in crop competitive ability for the whole cycle | Narrow-row spacing, bidirectional sowing, twin-row system, etc., contribute in smothering weeds. |

| Crop planting/sowing date | Improvement in crop competitive ability in early stages | A planting/sowing date in correspondence of the most suitable meteorological conditions allows the crop germinating/emerging before weeds and, thus, competing better for nutrients, water, light and space. |

| Crop transplant | Improvement in crop competitive ability in early stages | Transplanted crops have a shorter critical period and an easier mechanical or chemical control than sown crops. |

| Common Name | Binomial Name | CPWC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| canola | Brassica napus L. | 17–38 DAE | [81] |

| carrot | Daucus carota L. | up to 930 GDD when seeded in late April 414 to 444 GDD when seeded in mid to late May | [82] |

| chickpea | Cicer arietinum L. | from 17–24 to 48–49 DAE | [83] |

| corn | Zea mays L. | from the 3rd to 10th leaf stage | [78] |

| cotton | Gossypium hirsutum L. | from 100–159 to 1006–1174 GDD | [84] |

| leek | Allium porrum L. | 7–85 DAE | [85] |

| lentil | Lens culinaris Medik. | 447–825 GDD | [86] |

| penaut | Arachis hypogaea L. | 3–8 weeks after planting | [87] |

| potato | Solanum tuberosum L. | from 19–24 to 43–51 DAE | [88] |

| red pepper | Capsicum annuum L. | 0–1087 GDD (from germination to harvest) | [89] |

| rice | Oryza sativa L. | 30–70 days after transplant | [14] |

| soybean | Glycine max (L.) Merr. | up to 30 DAE | [90] |

| sunflower | Helianthus annuus L. | 14–26 DAE without preherbicide treatment 25–37 DAE with preherbicide treatment | [91] |

| tomato | Solanum lycopersicum L. | 28–35 days after planting | [92] |

| white bean | Phaseolus vulgaris L. | from the second-trifoliolate and first-flower stages of growth | [93] |

| winter wheat | Triticum aestivum L. | 506–1023 GDD | [94] |

| Methods Involved | Type of Integration | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical–Physical | Hoeing–Brush weeding | A combined hoeing close to the row plus vertical brush weeding increases weed control efficiency. | [111] |

| Physical–Mechanical | Banded flaming–Cultivator | A banded flaming intra-row followed by aggressive mechanical cultivation inter-row provides over 90% of weed control in organic maize. | [112] |

| Mechanical–Biological | Reduced tillage–Bioherbicides | In zero- or minimum-tillage systems, weed seeds concentrate in the upper soil layer, thus allowing the surface application of bioherbicides with seed-targeting agents. | [113] |

| Biological–Chemical | Bioherbicide–Herbicide | Combining the pre-emergence inoculation with the fungal pathogen Pyrenophora semeniperda and post-emergence imazapic application limits the spread of cheatgrass. | [114] |

| Chemical–Mechanical | Herbicides–Hoeing | The integration of herbicides intra-row and hoeing inter-row allows halving herbicide’s amount in maize, sunflower and soybean, with no loss in weed control and crop yield. | [115] |

| Chemical–Mechanical | Herbicides–Ploughing | The integration of pre-sowing and pre-emergence herbicides with post-emergence inter-row cultivation increases yields and reduces total weed density in a cotton-sugar beet rotation. | [116] |

| Technique | Allelopathic Source | Target Weeds | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop rotation | Glycine max (L.) Merr., Triticum aestivum L. | Setaria faberi Herrm. | Corn following wheat in a soybean–wheat–corn rotation significantly reduced giant foxtail population. | [128] |

| Intercropping | Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper | Echinochloa colona (L.) Link, Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop, Setaria glauca (L.) Beauv. | Intercropping black gram in a rice field was very effective in suppressing weeds and increasing crop yields. | [131] |

| Mulching | Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench | Cyperus rotundus L., Trianthema portulacastrum L., Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., Convolvulus arvensis L., Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) Willd., Portulaca oleracea L. | Surface-applied sorghum mulch at sowing in maize reduced weed density and dry weight. | [132] |

| Green manure | Brassica nigra L. | Avena fatua L. | Soil incorporation of both roots and shoots of black mustard significantly decreased wild oat emergence, height and dry weight per plant. | [133] |

| Bioherbicide | Juglans nigra L. | Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist, C. bonariensis, P. oleracea, Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth | The black walnut extract-based commercial product (NatureCur®) decreased the germination and seedling growth of target weeds. | [134] |

| Water extract + Herbicide | S. bicolor, Helianthus annuus L., Brassica campestris L. | T. portulacastrum, C. rotundus, Chenopodium album L., Cronopus didymus L. | The combined application of a mixed water extract from sorghum, sunflower and mustard with pendimethalin allows for reducing herbicide rate. | [135] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G. Integrated Weed Management in Herbaceous Field Crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10040466

Scavo A, Mauromicale G. Integrated Weed Management in Herbaceous Field Crops. Agronomy. 2020; 10(4):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10040466

Chicago/Turabian StyleScavo, Aurelio, and Giovanni Mauromicale. 2020. "Integrated Weed Management in Herbaceous Field Crops" Agronomy 10, no. 4: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10040466

APA StyleScavo, A., & Mauromicale, G. (2020). Integrated Weed Management in Herbaceous Field Crops. Agronomy, 10(4), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10040466