Abstract

The medicinal and aromatic plant (MAP) sector in Italy is a niche sector that is growing in terms of both primary production and consumption. These products seem to be important to address several global challenges, including climate change, biodiversity conservation, drought solutions, product diversification, product innovations, and the development of rural areas (rural tourism in primis). This study utilised the Delphi method to identify key factors and possible strategies that could be adopted for the future (the next 3–5 years) of the national MAP supply chain. The research involved the collaboration of 26 experts. Individual interviews, based on a semi-structured questionnaire, were carried out during the first round of the study. The information and the collected data were then analysed and depicted in a mental map. The Italian MAP sector suffers from competition from lower-cost imported products. Despite this, the experts predicted an expansion of the MAP sector regarding aromatic herbs and certain derivative products, such as dietary supplements, biocides, and essential oils. The experts anticipated the need to increase the adoption of digital innovations, of developing agreements among the actors of the supply chain, and of investing in the training of supply chain actors.

1. Introduction

The cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) is growing on the international market, especially concerning spices, herbs, and essential oils [1]. By promoting the cultivation of these plants, farmers, particularly those in the most disadvantaged and marginalised geographical areas, can potentially unlock new and sustainable business opportunities. This presents them with a chance to tap into emerging markets [2]. In addition, because of the effects of climate change, which are modifying the agro-ecological conditions in the Mediterranean basin, the introduction of MAPs could represent a rational and possible solution to limit and slow down these phenomena.

These crops could be used to replace or complement monocultures, thus increasing agricultural biodiversity and restoring the fertility of soils. Moreover, most of these MAPs are collected from the wild [3]—approximately 2000 species (1200 native varieties) in the Mediterranean area [4]—and are crucial for economic development and rural employment [5,6,7,8].

From an economic perspective, they provide essential inputs for the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and perfume industries, as well as for agribusiness [9], and are traded as commodities or as processed products on international markets.

The ongoing substantial growth in the worldwide demand for MAPs has presented exporting nations with a chance to improve their participation in this sector by developing alternative processing techniques [1]. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data on the economic worth of MAPs, which may be either wild or farmed, since much of the trade occurs informally [10,11]. According to recent statistics from FAOSTAT [12], the global cultivated area of MAPs in 2021 amounted to 12.7 million hectares throughout the world (2.4% in Europe); the harvested production was equal to 90.8 million tonnes (5.5% in Europe); the imports reached approximately 9 million tonnes and 21.2 million USD (of which 36% and 38% were from Europe, respectively); and the exports reached 9.2 million tonnes and 21 million USD (of which 26.6% and 28% were from Europe, respectively). In order to complete the quantitative picture of the MAP market, the following additional data are proposed. Today, the MAP trade is worth more than 68 billion USD [13]. The European Union (EU) imports MAPs worth around 1 billion USD from Asia and Africa [14]. Furthermore, the statistics for the 2011–2020 period indicate that MAP exports increased by 5% and reached 68.5 million USD [13].

In Italy, approximately 24,000 ha are cultivated with MAPs (of which 6200 ha are organic). Most of the production (35.5%) is found in four regions: Marche, Apulia, Emilia-Romagna, and Tuscany [15,16]. Although there are about 150 cultivated species, most of the MAP production (70%) is collected from the wild. The production of MAPs has now reached 4000 tonnes (excluding coriander), and 350 tonnes of essential oils are produced, mainly from bergamot. The estimated value of the production is 235 million EUR. However, Italy also imports 7000 tonnes of MAPs and their derivatives, for a total value of 47 million EUR. Of the 300 marketed species, 26,000 tonnes are exported [16].

In general, processors or farmers sell dried MAPs to wholesalers, who then distribute the product to other industries or retailers. Only small retailers or supermarkets offer fresh MAPs. Unlike fresh MAPs, dried MAPs may be kept for a long period and exported as a result of their low moisture content. Considering the environmental and economic opportunities that may be derived from these crops, it is of great importance to forecast the evolution of the market.

2. Theoretical Background of the Research and Its Objectives

This study aimed at gathering the viewpoints of national experts in the MAP sector in Italy to assess their understanding of the current state of the national MAP industry to identify the obstacles to and the necessary actions for the growth of the sector and to investigate future market trends and developments in the MAP supply chain in Italy while acknowledging the challenge of making accurate predictions. The study also dealt with the future evolution of the MAP sector by implementing a two-round Delphi study of the Italian MAP supply chain.

2.1. Delphi-Based Literature on Crops and Agricultural Production

Foresight is one of the most attractive fields of study [17]. It is used to design appropriate strategies to achieve specific goals. Various methodological techniques can be employed in the agricultural sector to contextualise the concerns of future scenarios that involve stakeholders [18]. Among these, the Delphi method is particularly relevant since it yields substantial findings in both qualitative and quantitative terms. It is a useful methodological approach to building future scenarios on specific themes [19]. The process relies on the results of several rounds of questionnaires submitted to a pool of experts. This method allows the participants to reach a mutual agreement or consensus [20]. As noted by Landeta [21], there exists a contrast between the seemingly simple nature of the Delphi method and the actual effort and complexity required for its execution. The traditional design of the Delphi method incorporates several distinct characteristics [22], it involves an iterative process (which requires experts to be consulted at least twice for each question), ensures participant anonymity, necessitates controlled feedback, and yields a statistical response from the group. This implies that all the collected opinions contribute to the final response and can be analysed using quantitative and statistical methods.

The Delphi method is a fairly common technique in the scientific community, especially in the social sciences and business fields [20]. It has been extensively utilised to evaluate different scenarios [23,24,25], and it is widely used in strategic planning and forecasting in the manufacturing industry and entrepreneurship [26,27]. In addition, this technique has also been used to analyse the agricultural sector [28,29], as well as various agri-food markets [30,31,32,33,34]. However, only a limited number of researchers have used this strategy to investigate the production and commercialisation of MAPs. Taghouti et al. [5] recently examined the current state of the MAP sector in the most productive Mediterranean countries. They highlighted future challenges, in particular those concerning product certification and labelling, market development, research, and processing. Noorhosseini et al. [35] studied the drivers and inhibitors of MAP cultivation in an Iranian metropolis. The primary issues they identified, via the Delphi method, included the lack of knowledge about the production of MAPs, the absence of herbalist businesses in the provinces, and the lack of collaboration between research centres and environmental authorities.

The objective of the present study was to employ the Delphi method to anticipate future MAP market scenarios, with a focus on the Italian market.

2.2. Objectives

On the basis of the existing literature, and given the growing importance of the MAP sector, the main purpose of this study was to build the market scenario for MAPs for the next 5–10 years in order to better understand the expectations and potential of the sector. Two other objectives were to identify any critical issues and the drivers of the development of the whole supply chain and to develop useful strategies for the future of the Italian MAP supply chain. In this regard, the study considered the following issues: a scenario analysis of the major competing countries, the primary challenges that have to be faced, and the outlook of the future market. A two-round Delphi method was used, starting from the current situation of the MAP sector in Italy. Through this methodology, the authors were able to shape, through the perceptions and opinions of experts, reliable future trends that could have an impact on the MAP sector.

3. Procedures and Participants

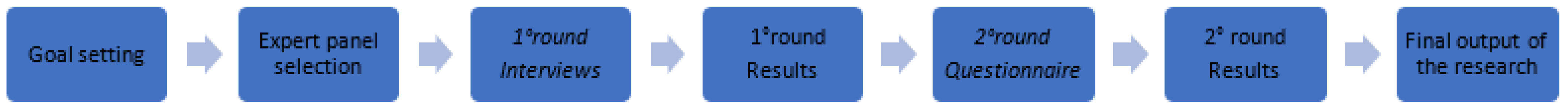

The Delphi survey method was carried out in two steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the adopted method.

The experts were classified into the following categories, with the number of respondents indicated in brackets: agricultural entrepreneurs (six); processors (seven); herbalists (three); traders (three); nurserymen (one); landscape architects (one); representatives of federations/associations (three); and ministerial employees (two).

Table 1 illustrates the steps of the survey and the types of questions the experts were asked.

Table 1.

Two-step Delphi survey.

3.1. First Round

The first round was conducted between January and March 2022. Several scientific articles regarding the MAP supply chain were consulted and studied in depth. A group of experts was then identified to tackle the task and 26 key informants were selected.

There is no consensus on the correct number of participants to use in a Delphi survey [35]. Some scholars propose that between five and twenty panellists are satisfactory [36]. Other authors believe that a small number of experts may not be representative and suggest that the larger the panel, the more reliable it is [37]. However, there are those in the scientific community who argue that the Delphi technique does not require expert panels to be representative for statistical purposes since representativeness is evaluated by the quality of the panel rather than its size [38].

The choice of the experts who are invited to participate in a survey is a very important aspect and, probably, the key to the success of the entire process [39]. This choice is critical, not only in terms of cooperation with the researcher who is leading the process but also, especially, in terms of the experts’ expertise and knowledge on the topic, because the results will depend on these aspects. The selected participants all worked in different stages of the MAP supply chain, which made this approach interesting, as it offered a range of different viewpoints.

Once the experts had been identified, individual open interviews, based on a semi-structured questionnaire, were carried out. Given the number of participants and their wide geographic distribution, each was interviewed online through the WebEx platform. Each response was noted, and, at the same time, all the interviews were recorded. The interviews lasted about 45 min each on average, and the contents of the interviews were analysed carefully at a later stage. The use of the online platform facilitated the data collection process. Considering the need to gather opinions from geographically distant participants, it would have taken much longer if face-to-face interviews had been conducted.

The second-round questionnaire was constructed on the basis of this information and the collected data, which were depicted in a mental map.

3.2. Second Round

This phase lasted from April 2022 to July 2022. The results of the survey were processed using Google Forms, and the responses were handled completely anonymously. The group of experts had to provide their opinions about certain statements by expressing their agreement or disagreement using a 5-level Likert scale, e.g., completely disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, completely agree.

There has been some criticism concerning the anonymity of experts in the responses to questionnaires as being a potential cause of biased results since they may feel that they do not have to invest the necessary time and energy to answer the questions [35]. However, according to other authors, the anonymity underlying Delphi research encourages participants to be honest, and this in turn mitigates the risk of the “halo effect” [40], which is when the opinions of dominant or prominent key informants receive greater credibility [41].

The answers to each item by the experts were transformed into arithmetic means: values of ≤3.00 were considered of ‘lesser importance’, values from >3.00 to ≤3.50 were considered of ‘medium importance’, and values of >3.50 were considered of ‘major importance’. A value of 3.00 was chosen because it represented about 60% of the answers, while 3.5 was chosen as it corresponded to 70% of the answers. Moreover, according to previous studies [21], answers with a higher IQR than 2.0 were not analysed because this value indicates that the agreement (consensus) between the experts is too low.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. First-Round Results

We reported the results of the first round in a mental map, which is a useful strategy to obtain a clear and comprehensive view of the main concepts that emerged during the interviews and their connections. A mental map is structured with nodes that radiate out from a central concept. In the present case, the nodes are the main topics that arose from the interviews with the experts. We obtained 10 nodes related to the MAP supply chain and these nodes were connected, through branches, to keywords (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Thematic nodes and topics identified during the first round.

The results were used to identify and summarise the potential outcomes of the general consensus with regard to the four topics listed below:

- Competitors and consumers of Italian MAP production;

- Market evolution of MAPs in Italy;

- Critical factors of the Italian MAP supply chain;

- Future developments and suggestions to improve the Italian MAP supply chain.

A more structured, closed-ended questionnaire, consisting of 26 questions, was administered in the second phase to collect more quantitative data.

4.2. Second-Round Results

The results of the second round were analysed to draw up the future scenario of the Italian MAP sector over the next 3–5 years. Each topic collected a certain number of answers in the questionnaire. The answers were analysed, and the arithmetic mean, the standard deviation, and the interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for each of them.

4.2.1. Competitors in Italian MAP Production

As far as international competitiveness is concerned (Table 2), the experts believed that the main competitors were countries that border the Mediterranean Sea, both outside the EU, including Turkey, Israel, and North African countries, and within the EU. The largest MAP-growing area within the EU is in Poland, followed by Hungary and Romania [16].

Table 2.

Competing producing countries.

Nevertheless, the role of other EU Mediterranean countries is equally important. Over the next five years, Spain, Portugal, and Greece will compete actively in the MAP sector. This opinion of the experts has been confirmed by many authors [18]. Moreover, these outcomes can be fully corroborated by the growing increase in the cultivated areas of MAPs [17,18,42]. The primary European MAP production countries are Bulgaria (20.2%), Spain (19.4%), Italy (8.4%), Poland (7.0%), and Turkey (10.0%). Moreover, the productions in France, Greece, Hungary, Albania, and Finland are also noteworthy [43,44,45]. Many MAPs originate from the Mediterranean area (rosemary, sage, oregano, thyme, peppermint, and garlic) where they are either cultivated or collected from the wild. It has been estimated that 80% of the MAPs in this area are collected from the wild, thus underlining the role they play in rural development [9,46]. In addition, it has been concluded that Asian countries, especially China, will become even more relevant. This appears to be in line with a study on the opportunities for Italian MAPs outlined in the 2018 legislation [47]. As pointed out by most of the experts, the key competition for Italian MAP products is from low-cost imports, despite the superior quality of the Italian products [48]. Furthermore, competition from Latin American and South African countries should not be ruled out in the next few years.

4.2.2. The Market Evolution of MAPs

The experts were then asked to identify which countries presented the best opportunities for market growth in the near future (Table 3). According to our results, a positive trend can be expected for the consumption of Italian MAPs in EU countries that are traditional consumers: Central European countries, primarily Germany, but also France and Holland and, albeit to a lesser extent, Scandinavian countries. This trend is confirmed by official statistics: the European MAP market, albeit only for the primary production of MAPs, is valued at 4–5 million EUR (about 400,000–450,000 tonnes of herbs and dried herbs and more than 100,000 tonnes of essential oils) [12].

Table 3.

Future market expansion.

MAPs are marketed in many forms, including fresh, dried, and as herbal teas, and many are used to extract high-value chemicals, such as essential oils [49,50,51]. At present, about 25% of newly marketed medications are derived from natural compounds, the vast majority of which are MAPs [52]. Consequently, any increase in domestically processed MAPs is expected to be absorbed by the international market for use as dietary supplements (mean of 3.52), spices, essential oils, and aromatic herbs. The respondents also forecasted that infusions and biocides will experience significant growth in the near future (Table 4).

Table 4.

Expected growth of MAP industries on the international market.

The forecasted development of biocides is largely due to the introduction of new regulations in the US and EU which limit the use of synthetic pesticides [53]. The experts hypothesised that the market opportunities for liqueurs, pet foods, and ornamental potted plants would not grow significantly, as evidenced by their low mean values. Our findings seem to be partially consistent with the existing statistics and literature. It is believed that more than three-quarters of the world’s population consume MAPs [9] and that the worldwide trade in MAPs is expanding at an annual growth rate of 10–12% [54].

4.2.3. Critical Factors of the Italian MAP Supply Chain

The subsequent analysis of the MAP supply chain at a national level identified several critical factors (Table 5).

Table 5.

Critical factors of the Italian MAP supply chain.

The increasing competition from imported products is closely linked to their lower price. Although the bargaining power of distributors is not a critical factor, the low selling prices of MAP are, as evidenced in studies and documents linked to the Ministry of Agriculture [48]. The selling prices of the primary production, that is, dried herbs in general and also processed ones, are considered low compared to the cost of production. In Italy, most of the national production is concentrated in small and marginal (mainly hilly or mountainous) areas, which produce low yields and have little to no mechanisation [48].

The lack of coordination among producers was indicated as the most critical factor (mean of 3.68). The lack of coordination hinders, among other things, the possibility of producers presenting themselves to buyers with a sufficient critical mass of products, which should translate into better prices. This was followed by the joint purchase of machinery and equipment for the initial processing, which should result in a reduction in the cost of production and the need for improved promotional activities [48,55].

Knowledge, which in our study refers to cultivation (agronomic) and the first and second processing techniques (both at a farm level and at a processing level), seems to have barely been highlighted. There was no consensus among the experts about this issue, as indicated by the high IQR values. Regarding knowledge, it should be recalled that the literature, in general, highlighted a link between knowledge and the cultivation of MAPs. It was revealed that the amount of knowledge has a significant impact on the interest of farmers in MAP farming [56]. In addition, Suganthi [57] and Nagar [58] argued that a proper understanding of MAP cultivation by farmers would lead to an increased acceptance of MAPs, a theory that was subsequently validated by Abadi et al. [59] who demonstrated that the knowledge variable has the most impact on the adoption of MAP cultivation.

The experts also indicated a lack of supply chain agreements, which prevents producers from adjusting the quantity and quality of production, determining the species cultivated, defining the prices, and developing collective brands and promotion activities, as pointed out by Manzo et al. [48]. In this regard, the recent national legislation on MAPs (drawn up in the year 2018) offers the possibility of creating regional and/or national brands [47]. Supply chain agreements can be used to increase coordination among the operators and could allow the internal market to be better managed.

4.2.4. Future Developments and Suggestions to Improve the MAP Supply Chain in Italy

Finally, the experts were asked to identify the main strategies that could be adopted to develop and improve the Italian MAP supply chain (Table 6). Although working on a closed supply chain was not considered useful to relaunch the sector, the importance of cooperation among producers was pointed out. In fact, ‘cooperation among producers’ was indicated as the most important strategy to improve the supply chain (mean of 3.96). This was followed by the necessity of training courses for supply chain operators. The introduction of digital innovation and, more in general, of high-level technologies also received high consensus (mean of 3.44).

Table 6.

Actions that could be taken to improve the Italian MAP supply chain.

Cooperation among producers is important to enlarge the size of the supply chain and to allow Italian producers to be more competitive. This result appears to be fully confirmed by the current literature [60,61]. In fact, the number of agricultural plots owned by locals, the size of the land [62], and the relative land use are the factors that have the most influence on the consumption and trade of MAPs in numerous regions [63]. Moreover, the proportion of farm income has a beneficial impact on the possibility of adopting actions to extend the cultivation area and of adopting new crops [63,64,65,66,67,68].

In regard to training, a general consensus emerged about the need for more in-depth investments to encourage the entrance of younger and better trained entrepreneurs; age and level of education have emerged as important factors. Abadi et al. [62] and Spina et al. [69] suggested that younger farmers have a greater understanding of land management measures and are more familiar with innovations and the adoption of new cultivation technologies.

Digital innovation also received a great deal of attention in identifying actions that could improve the MAP supply chain. This aspect may be traced back to what was mentioned about the need to increase coordination between producers and operators in the supply chain. New technologies and, in particular, the possibility of creating a national platform where data on production, processing and trading companies, quantities and types of MAPs, costs and prices, imports and exports, promotion initiatives, etc., could be displayed was considered essential to overcome the chronic lack of statistical data on the sector and the lack of information exchange between operators [48].

According to the experts, to promote an expansion of the supply chain, it would be necessary to investigate the potential of MAPs to maximise their value, promote their sustainable production, and facilitate their trade for the benefit of farmers and the environment. There are two components that underlie the production of MAPs: pull effects and push effects. Pull effects are those elements that entice farmers to plant MAPs, such as attractive prices, fixed market channels, price guarantees, and producer group monopolies in the cultivation of these commodities [70].

The push factors, on the other hand, are driven by the volatility of the net revenue of conventional seasonal crops. Hence, more structured governance could allow further growth of the supply chain. Only a few studies have explored the governance of the global MAP value chain [71].

The second-round results pointed out that the cultivation of MAPs in Italy can be expected to increase in the near future. The trend of aromatic plants such as thyme, oregano, rosemary, and sage appears to be particularly significant, but also that of helichrysum and mint. Only three species had a result that was ‘not significant’: hypericum, rhubarb, and liquorice, the latter of which is typically produced in southern Italy (Table 7).

Table 7.

MAP species with the greatest potential in Italy and the preservation of biodiversity.

On the other hand, when considering the number of marketed species, only a few hundred are expected to be derived from cultivation [72], thus demonstrating that most commercialised plant species are still gathered from natural areas.

This study has also endorsed the link between MAPs and biodiversity preservation. The importance of MAPs, regarding biodiversity preservation, is always considered to justify or to ask for public intervention for the MAP sector at a national-EU level [73]. In addition, these plants provide numerous environmental benefits. One of the extra benefits of these plants is that they thrive in water-deficient environments [74]. Indeed, the essential oil yield/quality and antioxidant and insecticidal ability of MAPs are enhanced in water deficiency situations [75].

Moreover, MAPs are essential components of ecosystems; hence, sustainable harvesting procedures should be used to establish a balance between sustainable management and commercialisation in order to conserve and perpetuate biodiversity [9,76].

The trade in MAPs leads to an increase in the agricultural GDP of all the nations that have an agricultural basis or natural vegetation-rich regions. Indeed, this type of crop has been recommended in rural regions as a means of increasing revenues and resolving agro-food preservation difficulties [77]. The importance of MAPs for rural areas has also been pointed out in Italy where they occur in 20.6% of the territory and interest 47.2% of the population [16]. However, specific interventions for this sector have never been foreseen within the EU rural development policies, and MAPs have been excluded from other direct interventions by the EU.

The national MAP sector has benefited from certain rural development subsidies (Rural Development Programmes for 2014–2020) under specific measures, such as biodiversity conservation and production diversification [73,78], and it has been included in policies directed towards the forestry sector, as they are non-wooden forestry products (NWFP) and, as such, are included in agroforestry programmes [6].

The economic indicators of MAPs are influenced, both locally and globally, by a variety of socio-economic, cultural, environmental, and geographical aspects [79]. There are numerous places in Italy where MAPs, many of which are typical, local species or varieties recognised for their high quality, have always been cultivated. Mint from Piedmont, liquorice from Calabria, and saffron from Abruzzo are just a few examples. Currently, cultivation in typical areas is often promoted through initiatives, most of which are local and often uncoordinated, of various kinds (e.g., festivals, fairs, and educational trails). These initiatives have used MAPs as a common denominator to promote territories [55].

Moreover, the ability of MAPs to increase the proportion of a farm’s income can have a beneficial effect on the possibility of adopting actions to extend a cultivation area and adopt new crops [64,65,66,67,68]. It has been underlined in several studies that MAPs can contribute to the integration of farm income and the diversification of production. Moreover, MAPs are crops that are mainly grown on small plots and often with a ‘female connotation’ [73,80].

Finally, an obstacle to the development of the Italian MAP sector is the lack of sufficient statistical and economic data at a national level, and the results of only a few studies that have taken into account certain specific realities, a few species, and even dated data are available. On the other hand, there has clearly been a renewed interest in MAPs in recent years given the many initiatives that have been put in place, especially at a regional level (e.g., Basilicata and Abruzzo).

5. Conclusions

It is of crucial importance to investigate the potential of MAPs in order to maximise their value, promote their sustainable production, and facilitate their trade for the benefit of farmers and the environment. We have attempted to move in the direction of “how it is” and “how it could be”, without having the pretension of the oracle, from whom Delphi takes its name.

The medicinal plant-based industry is a promising sector and a potential source of enormous economic growth [81]. Thanks to their different possible uses, MAPs have entered different markets, including the food industry, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, landscape architecture, etc. Moreover, in the last 20 years or so, there has been an increasing tendency towards the use of medicines derived from MAPs rather than medicines of chemical origin [82]. It has been estimated that pharmaceutical products derived from MAPs will grow globally to about 39.6 billion USD by 2022, with a growth rate of 6.1% per year for the 2017–2022 four-year period [1].

MAPs are low-input crops, they do not require large quantities of water since they adapt well to the different microclimates of the Italian and Mediterranean areas. Consequently, the ecology of the territory benefits from their cultivation. It has also been shown that these plants have a positive effect on the Mediterranean environment, as they play an active role in protecting the soil against erosive, climatic, and atmospheric phenomena. The most environmentally aware companies are currently looking for crops that require low management inputs; MAPs fully satisfy these requirements and they provide access to new and interesting markets and emerging job opportunities.

The MAP sector in Italy is less important than those of other crops, but it is growing—the cultivated area tripled from approximately 8000 to 24,000 ha in the 2010–2016 period—[15,16] and it is of interest, for now, mainly in rural and otherwise marginal areas. The average farm size is, in general, modest. Production, which is concentrated in four regions, is generally recognised as being of high quality, and many species constitute typical and local ‘market niches’.

Our study considered several aspects of the Italian MAP supply chain with the aim of providing suggestions for private and public operators for the future development (3–5 years) of the industry. It has emerged that the national MAP sector suffers from competition from lower-priced productions. This is due to the high production costs where cultivation is, which is, in general, practised in small plots and hilly or mountainous areas. Therefore, the possibility of mechanisation is limited. The main competitors are and will continue to be other Mediterranean (EU or non-EU) countries and Eastern European ones.

The experts have predicted an expansion in the cultivation of MAPs in Italy, especially for aromatic herbs (e.g., thyme, rosemary, and sage) and in general of their market, with an increase in exports mainly to northern EU countries and also to Germany. Supplements, essential oils, aromatic herbs, spices, and biocides will provide future market opportunities.

In spite of this positive trend, the Italian MAP supply chain suffers from several shortcomings, most of which are of an organisational nature. As pointed out by the experts, there are no coordinated actions between the players in the sector and there is a lack of supply chain agreements. A possible defence strategy is the training of farmers and increasing the amount of information they have at their disposal. This strategy could also include information about digital innovations and actions to support the expansion of the supply chain.

Currently, the interest in and the initiatives for the MAP sector are increasing (at both a national and regional level), and are linked to the development of rural or, more in general, marginal areas. Recent MAP legislation (2018) has drawn up regulations at a national level concerning cultivation and collection from the wild, defined what MAPs are, established a varietal register of MAPs, promoted the creation of collective brands, and included MAPs in the category of ‘agricultural activities’. Several regions, in collaboration with producers and their organisations, have also supported interventions to organise the supply chain (at a local or regional level). In addition, knowledge of the sector should be improved, from a statistical point of view.

In short, it has emerged from our study that the Italian MAP sector, despite its highlighted shortcomings, is expanding as a result of the growing interest in what is ‘natural’, the role of marginal areas, and the economic dimension of the market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.D., D.S. and G.D.V.; Methodology, D.S. and G.D.V.; Software, D.S.; Validation, M.D., D.S. and C.B.; Formal analysis, R.C., D.S. and M.H.; Investigation, R.C., D.S. and M.H.; Data curation, C.B., R.C. and G.D.V.; Writing—original draft preparation, D.S., G.D.V., M.H. and C.B.; Writing—review and editing, D.S., G.D.V., M.H., C.B. and R.C.; Supervision, M.D., G.D.V. and C.B.; Validation, M.D. and G.D.V.; Visualisation, G.D.V. and C.B.; Project administration, M.D.; Funding acquisition, M.D. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the PIAno di inCEntivi per la Ricerca di Ateneo (PIACERI) UNICT 2020/22 line 2 project, University of Catania (5A722192154) and the Local Research Fund 2022, and the University of Torino (person in charge of the scientific activities: Cinzia Barbieri).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (M.H.).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the experts involved in the research. Thanks are also due to Marguerite Jones for the English language revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ITC. Marketing Manual and Web Directory for Organic Spices, Culinary Herbs and Essential Oils, 2nd ed.; Technical Paper; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vita, G.; Spina, D.; De Cianni, R.; Carbone, R.; D’Amico, M.; Zanchini, R. Enhancing the extended value chain of the aromatic plant sector in Italy: A multiple correspondence analysis based on stakeholders’ opinions. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Mongin, C.; Hoxha, V.; Lerin, F. From total state to anarchic market: Management of medicinal and aromatic plants in Albania. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosta, R.A.; Moghaddasi, R.; Hosseini, S.S. Export target markets of medicinal and aromatic plants. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2017, 7, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Taghouti, I.; Cristobal, R.; Brenko, A.; Stara, K.; Markos, N.; Chapelet, B.; Hamrouni, L.; Buršić, D.; Bonet, J.A. The Market Evolution of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: A Global Supply Chain Analysis and an Application of the Delphi Method in the Mediterranean Area. Forests 2022, 13, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Emery, M.R.; Corradini, G.; Živojinović, I. New values of non-wood forest products. Forests 2020, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutke, S.; Bonet, J.A.; Calado, N.; Calvo-Simon, J.; Taghouti, I.; Redondo, C.; de Arano, I.M. Innovation networks on Mediterranean non wood forest products. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P. The medicinal and aromatic plants business of Uttarakhand: A mini review of challenges and directions for future research. Nat. Resour. Forum 2020, 44, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucholas, J.; Ukhanova, M.; Greinwald, A.; Luick, R. Wild collection of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) for commercial purposes in Poland-a system’s analysis. Herba Polonica 2021, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadou, K.; Sarropoulou, V.; Krigas, N.; Maloupa, E. In vitro propagation of Primula veris L. subsp. veris (Primulaceae): A valuable medicinal plant with ornamental potential. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 2020, 5, 532–539. [Google Scholar]

- Patelou, E.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Polidoros, A.N.; Mylona, P.V. Genetic diversity and structure of Sideritis raeseri Boiss. & Heldr. (Lamiaceae) wild populations from Balkan Peninsula. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2020, 16, 100241. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TCL (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Türkekul, B.; Yildiz, Ö. Medicinal and aromatic plants production, marketing and foreign trade. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Iksad Publishing House: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; pp. 3–43. ISBN 978-625-8007-73-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, W.; Rai, S.N.; Birla, H.; Singh, S.S.; Dilnashin, H.; Rathore, A.S.; Singh, S.P. The global economic impact of neurodegenerative diseases: Opportunities and challenges. In Bioeconomy Sustainable Development; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- CREA (Council for Agricultural Research and Analysis of Agricultural Economics). Annuario dell’Agricoltura italiana 2018; CREA: Roma, Italy, 2020; pp. 219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Borsotto, P. Piante Officinali Produzione e Consumo: La Competitività Delle Aziende Italiane. Convegno Piante Officinali: Aspetti Normative, Economici, Agronomici e di Trasformazione. Università degli Studi di Teramo. 11 luglio 2021. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/en/web/politiche-e-bioeconomia/-/piante-officinali (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Egfjord, K.F.H.; Sund, K. A modified Delphi method to elicit and compare perceptions of industry trends. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbà, A.S.; Di Vita, G.; Allegra, V. Strategy development for Mediterranean pot plants: A stakeholder analysis. Qual. Access Success 2013, 14, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. (Eds.) The Delphi Method, 3-12; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vita, G.; Allegra, V.; Zarbà, A.S. Building scenarios: A qualitative approach to forecasting market developments for ornamental plants. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2015, 15, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J.; Barrutia, J. People consultation to construct the future: A Delphi application. Int. J. Forecast. 2011, 27, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Kleer, R.; Piller, F.T. Predicting the future of additive manufacturing: A Delphi study on economic and societal implications of 3D printing for 2030. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 117, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, M.M.; Wright, G. Delphi method. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 1–16. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118445112.stat07879 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Féart, C.; Mann, G.; Viña, J.; Chatterji, S.; Chodzko-Zajko, W.; Gonzalez-Colaço Harmand, M.; Bergman, H.; Carcaillon, L.; Nicholson, C.; et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: A Delphi method based consensus statement. The frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Wright, R.W. International entrepreneurship: Research priorities for the future. Int. J. Glob. Small Bus. 2009, 3, 90–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Gracht, H.A.; Darkow, I.L. Scenarios for the logistics services industry: A Delphi-based analysis for 2025. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 127, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkonen, P.; Kaivo-oja, J.; Aakkula, J. Delphi expert panels in the scenario-based strategic planning of agriculture. Foresight 2006, 8, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, C.; Gabbai, M.; Zorini, L.O.; Pugh, B. Participatory scenarios for exploring the future: Insights from cherry farming in South Patagonia. Outlook Agric. 2012, 41, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; Fischer, A.R.H.; Wentholt, M.T.A.; Marvin, H.J.P.; Ooms, B.W.; Coles, D.; Rowe, G. The use of Delphi methodology in agrifood policy development: Some lessons learned. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Climent, V.; Apetrei, A.; Chaves-Ávila, R. Delphi method applied to horticultural cooperatives. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 1266–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badghan, F.; Namdar, R.; Valizadeh, N. Challenges and opportunities of transgenic agricultural products in Iran: Convergence of perspectives using Delphi technique. Agric. Food Secur. 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliach, D.; Vidale, E.; Brenko, A.; Marois, O.; Andrighetto, N.; Stara, K.; Martínez de Aragón, J.; Colinas, C.; Bonet, J.A. Truffle market evolution: An application of the Delphi method. Forests 2021, 12, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorhosseini, S.A.; Fallahi, E.; Damalas, C.A. Promoting cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for natural resource management and livelihood enhancement in Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 4007–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozuni, M.; Jonas, W. An introduction to the morphological Delphi Method for design: A tool for future-oriented design research. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2017, 3, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.S.; Stroud, W.J. General panel sizing computer code and its application to composite structural panels. AIAA J. 1979, 17, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.H.; Terry, H.R. Opportunities and obstacles for distance education in agricultural education. J. Agric. Educ. 1998, 39, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. Expert opinions in forecasting: The role of the Delphi technique. In Principles of Forecasting: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gundumogula, M. Importance of focus groups in qualitative research. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Moser, R. Biases in future-oriented Delphi studies: A cognitive perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 105, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, A.B.; Freitas, S. The Delphi method for future scenarios construction. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 5785–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/APRO_CPNHR/default/table?lang=enindustrial crop—Aromatic medicinalcrop (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Güney, O.I. Consumption attributes and preferences on medicinal and aromatic plants: A consumer segmentation analysis. Cienc. Rural 2019, 49, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.D.; Martinos, K.; Skoufogianni, E.; Danalatos, N.G. Medicinal and aromatic plants diversity in Greece and their future prospects: A review. Agric. Sci. 2016, 4, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S.; Bayramoglu, M.M. The trade and use of some medical and aromatic herbs in Turkey. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2013, 7, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. New 2018 Legislation for MAP in Italy. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 10, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, A.; Di Renzo, L.; Pistelli, L.; Colombo, M.L.; Dalfrà, S. La filiera delle piante officinali; Universitalia: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 259–292. ISBN 8865076674. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, R.; Žabka, M.; Vrchotová, N.; Tříska, J. Effect of foliar nutrition on the essential oil yield of Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, R.; Loying, R.; Sarma, N.; Munda, S.; Pandey, S.K.; Lal, M. A comparative study on antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, genotoxicity, anti-microbial activities and chemical composition of fruit and leaf essential oils of Litsea cubeba Pers from North-east India. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, C.M.; Coelho, K.P.; Luz, T.R.S.A.; Silveira, D.P.B.; Coutinho, D.F.; de Moura, E.G. Effect of different water application rates and nitrogen fertilisation on growth and essential oil of clove basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, U.B.; Lamsal, P.; Ghimire, S.K.; Shrestha, B.B.; Dhakal, S.; Shrestha, S.; Atreya, K. Climate change-induced distributional change of medicinal and aromatic plants in the Nepal Himalaya. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achimón, F.; Beato, M.; Brito, V.D.; Peschiutta, M.L.; Herrera, J.M.; Merlo, C.; Pizzolitto, R.R.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Zunino, M.P. Efecto insecticida y repelente de aceites esenciales obtenidos de la flora aromática argentina. Bol. Soc. Argent Bot. 2022, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITC. List of Exporters for the Selected Product. 2016. Available online: http://www.trade map.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Máthé, Á.; Hassan, F.; Kader, A.A. Medicinal and aromatic plants of the world. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants World; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vashishtha, U. An Assessment of Knowledge and Adoption of Chilli (Capsicum annum L.) Production Technology in Udaipur District of Rajasthan; MPUAT: Udaipur, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suganthi, N. Empowerment of Farmers through Cultivation of Medicinal Plants a Critical Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Madras, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nagar, S.N. Knowledge and adoption of recommended coriander cultivation technology among the farmers of Atru tehsil in Baran district of Rajasthan. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, MPUAT, Udaipur, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, B.; Azizi-Khalkheili, T.; Morshedloo, M.R. Farmers’ behavioral intention to cultivate medicinal and aromatic plants in farmlands: Solutions for the conservation of rangelands. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 75, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.; Ianuario, S.; Chinnici, G.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; D’Amico, M. Endogenous and exogenous determinants of agricultural productivity: What is the most relevant for the the competitiveness of the Italian agricultural systems? AGRIS On-Line Pap. Econ. Inform. 2018, 10, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Pilato, M.; Allegra, V.; Zarbà, A.S. Owner motivation in small size family farms: Insights from an exploratory study on the ornamental plant industry. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2019, 38, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, B.; Azizi-Khalkheili, T.; Morshedlooc, M.R. What factors determine the conversion of wild medicinal and aromatic resources to cultivated species? An intention and behavior analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Rauf, A. Medicinal plants: Economic perspective and recent developments. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 31, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, L. Study of factors affecting rapeseed area expansion in Kerman Province. Agric. Econ. Res. 2011, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Timpanaro, G.; Di Vita, G.; Foti, V.T.; Branca, F. Landraces in Sicilian peri-urban horticulture: A participatory approach to Brassica production system. In Proceedings of the VI International Symposium on Brassicas and XVIII Crucifer Genetics Workshop, Catania, Italy, 12–16 November 2012; pp. 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dashti, G.; Hayati, B.; Bakhshy, N.; Ghahremanzadeh, M. Analysis of factors affecting canola plantation development in Tabriz and Marand counties, Iran. Int. J. Agric. Manag. Dev. 2017, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ukamaka, A.T.; Umezinwa, F.N.; Okoli, I.M. Impact of improved ginger technologies on the income of cooperative farmers in Southern Kaduna, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Sumerianz. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.; Hansra, B.S.; Burman, R.R. Determinants and income generation from improved varieties in lower shivalik range of Uttarakhand, India. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, D.; Vindigni, G.; Pecorino, B.; Pappalardo, G.; D’Amico, M.; Chinnici, G. Identifying themes and patterns on management of horticultural innovations with an automated text analysis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandresh, G.; Vaidya, M.K.; Sharma, R.; Dogra, D. Economics of production and marketing of important medicinal and aromatic plants in mid hills of Himachal Pradesh. Econ. Aff. 2014, 55, 364–378. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Yang, B.; Dong, M.; Wang, Y. Crossing the roof of the world: Trade in medicinal plants from Nepal to China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, U.W.E.; Leaman, D.; Cunningham, A.B. A comparison of cultivation and wild collection of medicinal and aromatic plants under sustainability aspects. Frontis 2006, 17, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, C. Public Funds Disbursement for the MAP Sector: 2007–2013. Med. Aromat. Plants 2015, 5, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Litskas, V.; Chrysargyris, A.; Stavrinides, M.; Tzortzakis, N. Water-energy-food nexus: A case study on medicinal and aromatic plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Laoutari, S.; Litskas, V.D.; Stavrinides, M.C.; Tzortzakis, N. Effects of water stress on lavender and sage biomass production, essential oil composition and biocidal properties against Tetranychus urticae (Koch). Sci. Hortic. 2016, 213, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindigni, G.; Mosca, A.; Bartoloni, T.; Spina, D. Shedding light on peri-urban ecosystem services using automated content analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, H.; Aldosari, A.; Ali, A.; de Boer, H.J. Economic benefits of high value medicinal plants to Pakistani communities: An analysis of current practice and potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulak, M. Bibliometric analysis of studies in medicinal and aromatıc plants for rural development. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelvaga, Latvia, 23–25 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, U.; Iqbal, S.; Sohail, M.I.; Samreen, T.; Ashraf, M.; Akmal, F.; Siddiqui, A.; Ahmad, I.; Naveed, M.; Khan, N.I.; et al. A comprehensive review on emerging importance and economical potential of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) in current scenario. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 34, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, M. How do small rural food-processing firms compete? A resource-based approach to competitive strategies. Agric. Food Sci. 2004, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gunjan, M.; Naing, T.W.; Saini, R.S.; Ahmad, A.; Naidu, J.R.; Kumar, I. Marketing trends & future prospects of herbal medicine in the treatment of various disease. World J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 4, 132–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B. Problems and Prospects of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Cultivation and Marketing: A Case Study from Sarlahi District. Master’s Dissertation, University of Tribhuran, Pakhara, Nepal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vines, G. Herbal Harvests with a Future: Towards Sustainable Sources for Medicinal Plants; Plantlife International: Salisbury, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).