Different Functional and Taxonomic Composition of the Microbiome in the Rhizosphere of Two Purslane Genotypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Experiment

2.2. Analyses of Plant Tissue

2.3. DNA Extraction and Illumina Sequencing

2.4. Sequencing Data Processing

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Data Availability

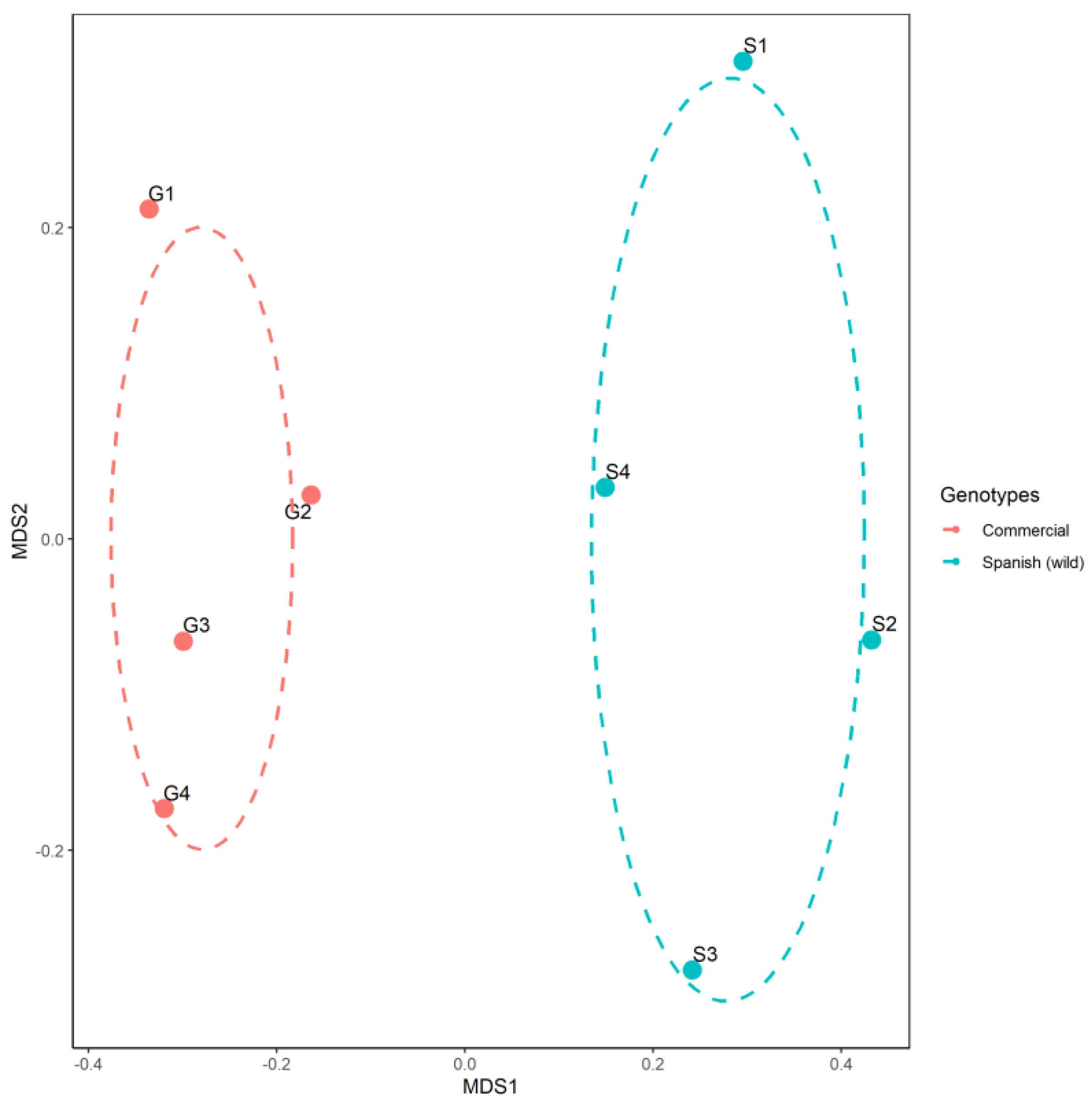

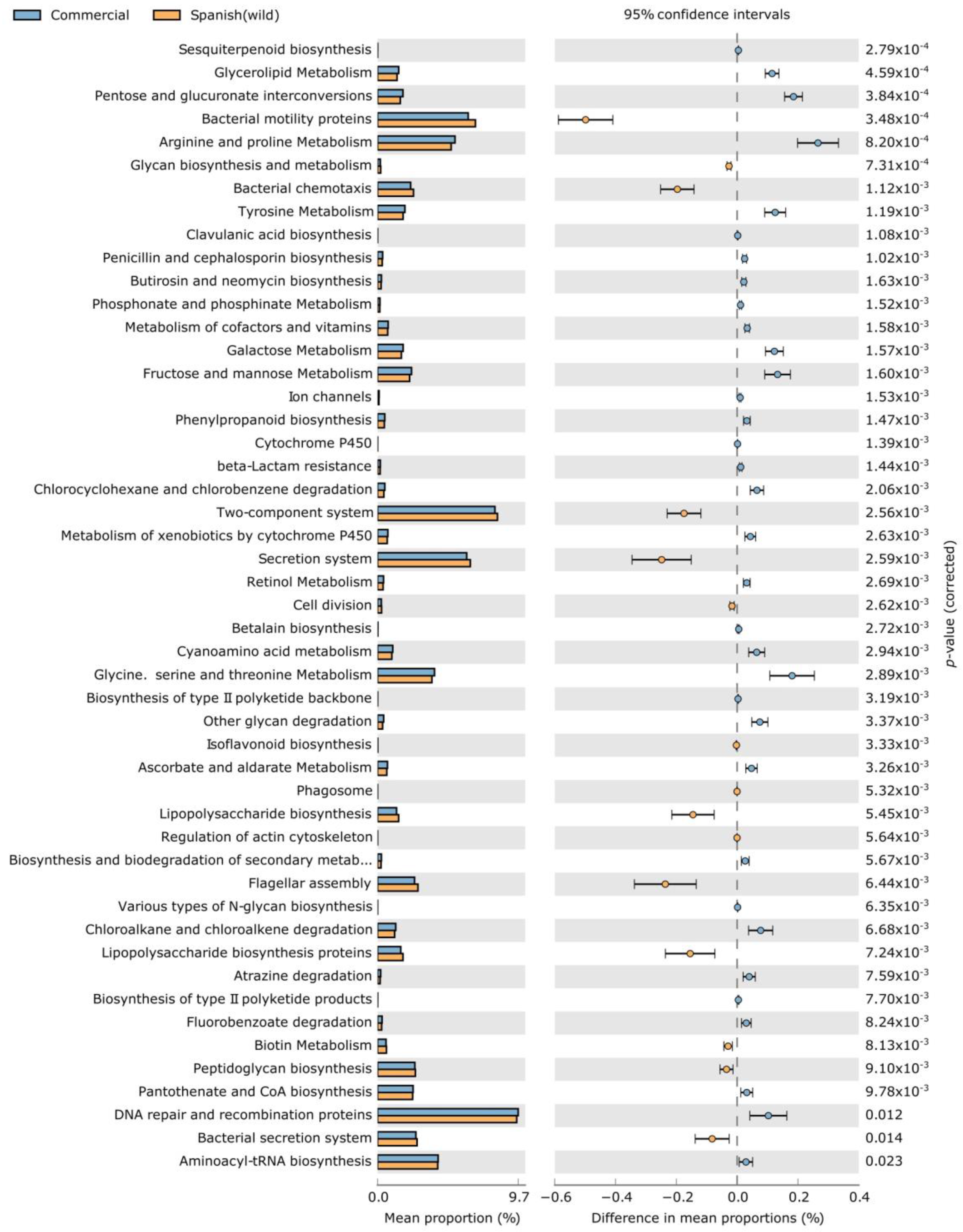

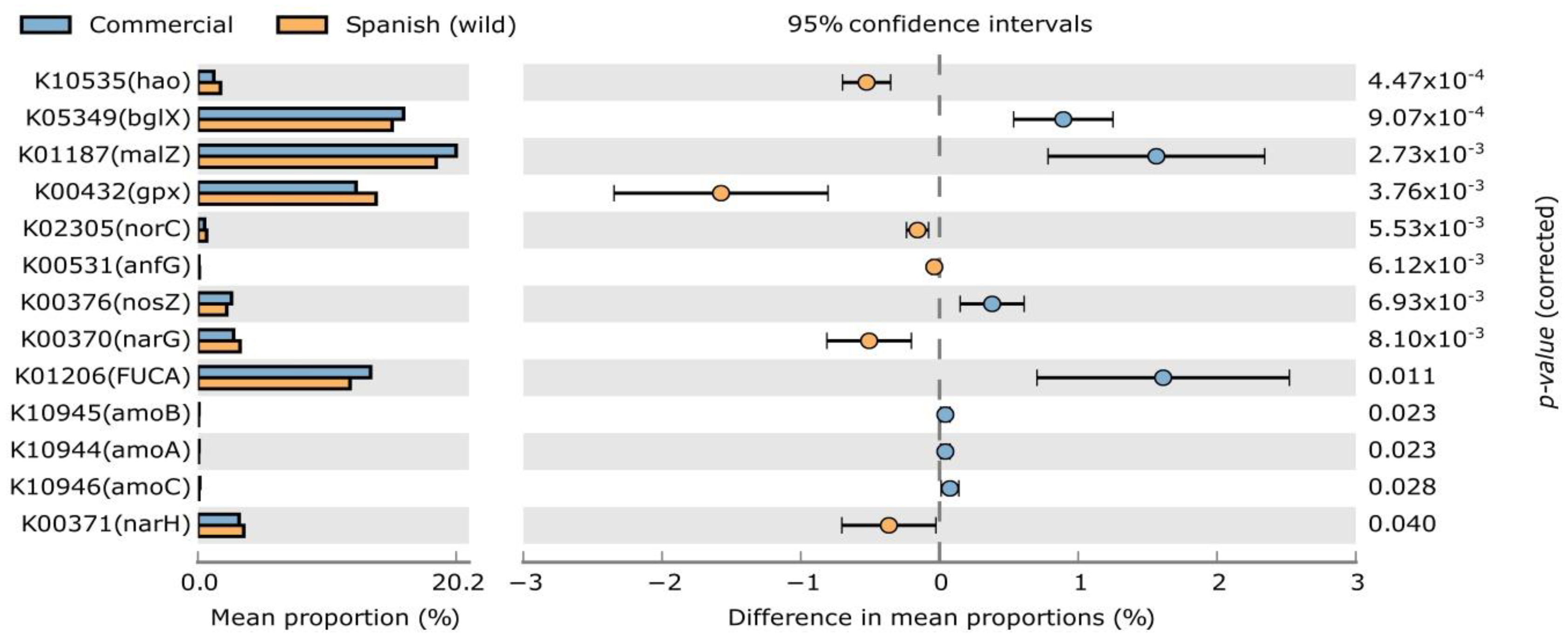

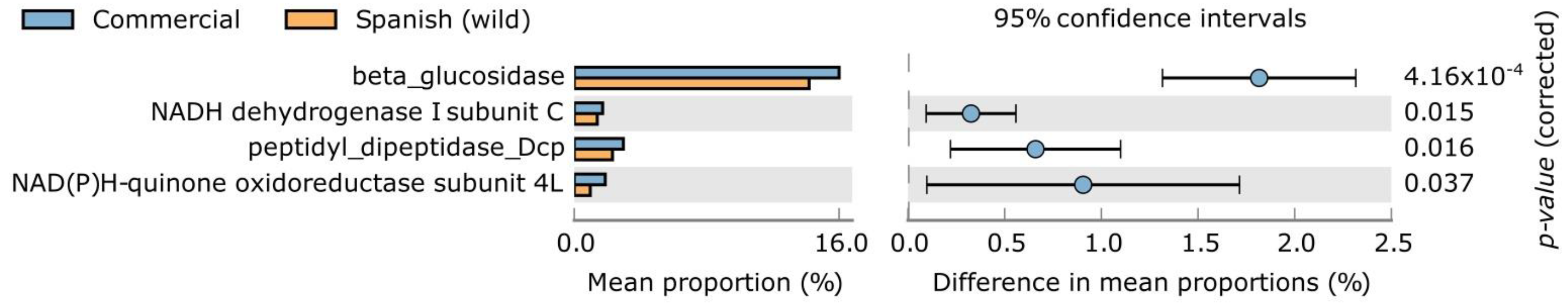

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, C.; Wu, C.; Gao, M.; Wang, Q. A review of root exudates and rhizosphere microbiome for crop production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54497–54510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, L.W.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; de Hollander, M.; Mendes, R.; Tsai, S.M. Influence of resistance breeding in common bean on rhizosphere microbiome composition and function. ISME J. 2018, 12, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, S.M.; Lear, G.; Case, B.S.; Buckley, H.L. The soil microbiome: An essential, but neglected, component of regenerative agroecosystems. iScience 2023, 26, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Shi, H.; Han, C.; Zhong, B.; Wang, Q.; Chan, Z. Physiological changes of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) after progressive drought stress and rehydration. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 194, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.; Karkanis, A.; Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical composition and bioactive compounds of common purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) as affected by crop management practices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-García, C.O.; Volke-Hallera, V.H.; Trinidad-Santosa, A.; Villanueva-Verduzco, C. Change in the contents of fatty acids and antioxidant capacity of purslane in relation to fertilization. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.A.; Karkanis, A.; Fernandes, Â.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.; Ntatsi, G.; Petrotos, K.; Lykas, C.; Khah, E. Chemical Composition and Yield of Six Genotypes of Common Purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.): An Alternative Source of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.A.; Fernandes, Â.; Dias, M.I.; Vasilakoglou, I.B.; Petrotos, K.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Nutritional Value, Chemical Composition and Cytotoxic Properties of Common Purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) in Relation to Harvesting Stage and Plant Part. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Tomita, J.; Nishioka, K.; Hisada, T.; Nishijima, M. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, D.S.; Yourstone, S.; Mieczkowski, P.; Jones, C.D.; Dangl, J.L. Practical innovations for high-throughput amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrmark, K.; Bödeker, I.T.M.; Cruz-Martinez, K.; Friberg, H.; Kubartova, A.; Schenck, J.; Strid, Y.; Stenlid, J.; Brandström-Durling, M.; Clemmensen, K.E.; et al. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region—evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslev, T.G.; Kjøller, R.; Bruun, H.H.; Ejrnæs, R.; Brunbjerg, A.K.; Pietroni, C.; Hansen, A.J. Algorithm for post-clustering curation of DNA amplicon data yields reliable biodiversity estimates. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarenkov, K.; Zirk, A.; Piirmann, T.; Pöhönen, R.; Ivanov, F.; Nilsson, R.H.; Kõljalg, U. Full UNITE+INSD Dataset for Fungi; UNITE Community: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Sato, Y.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package (R Package Version 2.5-5). 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- De Caceres, M.; Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: Indices and statistical inference. Ecology 2009, 90, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Tyson, G.W.; Hugenholtz, P.; Beiko, R.G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3123–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aira, M.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Lazcano, C.; Bååth, E.; Domínguez, J. Plant genotype strongly modifies the structure and growth of maize rhizosphere microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2276–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Münch, P.C.; Weiman, A.; Dröge, J.; Pan, Y.; McHardy, A.C.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and Function of the Bacterial Root Microbiota in Wild and Domesticated Barley. Cell Host Microb. 2015, 17, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, A.K.; Yin, C.; Hulbert, S.H. Community structure, species variation, and potential functions of rhizosphere-associated bacteria of different winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Hewezi, T.; Lebeis, S.L.; Pantalone, V.; Grewal, P.S.; Staton, M.E. Soil indigenous microbiome and plant genotypes cooperatively modify soybean rhizosphere microbiome assembly. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Terán, A.; Navarro-Díaz, M.; Benítez, M.; Lira, R.; Wegier, A.; Ana, E.; Escalante, A.E. Host genotype explains rhizospheric microbial community composition: The case of wild cotton metapopulations (Gossypium hirsutum L.) in Mexico. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, J.L.; Li, J.J.; Li, X.L.; Dai, X.J.; Shen, R.F.; Zhao, X.Q. Distinct Patterns of Rhizosphere Microbiota Associated With Rice Genotypes Differing in Aluminum Tolerance in an Acid Sulfate Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 933722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Widmer, F. Community structure analyses are more sensitive to differences in soil bacterial communities than anonymous diversity indices. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7804–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semchenko, M.; Xue, P.; Leigh, T. Functional diversity and identity of plant genotypes regulate rhizodeposition and soil microbial activity. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, S.C.; Kossmann, J.; Smith, A.M. Starch: Its metabolism, evolution, and biotechnological modification in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameer, S.; Prasad, T.N.V.K.V. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural practices with special reference to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Rasmann, S.; Yue, L.; Lian, F.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z. The effect of biochar amendment on N-cycling genes in soils: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Harrold, D.R.; Claypool, J.T.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W.; Simmons, C.W.; VanderGheynst, J.S. Nitrogen amendment of green waste impacts microbial community, enzyme secretion and potential for lignocellulose decomposition. Process Biochem. 2017, 52, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bayo, J.D.; Hestmark, K.V.; Claypool, J.T.; Harrold, D.R.; Randall, T.E.; Achmon, Y.; Stapleton, J.J.; Simmons, C.W.; VanderGheynst, J.S. The initial soil microbiota impacts the potential for lignocellulose degradation during soil solarization. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 1729–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S. Soil microbes are linked to the allelopathic potential of different wheat genotypes. Plant Soil 2014, 378, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.T.; Landi, L.; Pietramellara, G.; Renella, G. Microbial diversity and soil functions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2003, 54, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firáková, S.; Ṡturdíková, M.; Múcková, M. Bioactive secondary metabolites produced by microorganisms associated with plants. Biologia 2007, 62, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, V.; Selvaraj, G.; Bais, H.P. Functional soil microbiome: Belowground solutions to an aboveground problem. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Shi, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiang, W.; Wang, X. Lechevalieria rhizosphaerae sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from rhizosphere soil of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and emended description of the genus Lechevalieria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 4655–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custer, G.F.; van Diepen, L.T.A.; Stump, W. An Examination of Fungal and Bacterial Assemblages in Bulk and Rhizosphere Soils under Solanum tuberosum in Southeastern Wyoming, USA. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 1, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeda, D.P. The Family Actinosynnemataceae. In The Prokaryotes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 654–668. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, M.; Naziya, B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; AlYahya, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Thriveni, M.C.; Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, S.B.; Aiyaz, M.; et al. Bioprospecting of Rhizosphere-Resident Fungi: Their Role and Importance in Sustainable Agriculture. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella Species as the Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi Present in the Agricultural Soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Jie, X.; Hu, D.; Feng, B.; Yue, K.; et al. Rare fungus, Mortierella capitata, promotes crop growth by stimulating primary metabolisms related genes and reshaping rhizosphere bacterial community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Phyla | IndVal | p-Value | RA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish (wild) purslane | Elusimicrobia | 0.905 | 0.0298 * | 0.07 |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 0.825 | 0.0298 * | 2.39 | |

| Firmicutes | 0.823 | 0.0298 * | 0.19 | |

| WS2 | 0.807 | 0.0298 * | 0.19 | |

| Acidobacteria | 0.745 | 0.0298 * | 6.80 | |

| Proteobacteria | 0.740 | 0.0298 * | 28.2 | |

| Commercial purslane | Deinococcus-Thermus | 1.000 | 0.0298 * | 0.10 |

| Patescibacteria | 0.784 | 0.0298 * | 6.20 | |

| Bacterial genera | IndVal | p-value | RA (%) | |

| Spanish (wild) purslane | Bauldia | 1.000 | 0.0296 * | 0.09 |

| Craurococcus | 1.000 | 0.0296 * | 0.09 | |

| Candidatus Captivus | 0.968 | 0.0296 * | 0.27 | |

| Hirschia | 0.945 | 0.0296 * | 0.10 | |

| Quadrisphaera | 0.887 | 0.0296 * | 0.18 | |

| OM27 clade | 0.885 | 0.0296 * | 0.23 | |

| Haloactinopolyspora | 0.869 | 0.0296 * | 0.11 | |

| AKYG587 | 0.855 | 0.0296 * | 0.23 | |

| Sva0996 marine group | 0.853 | 0.0296 * | 0.11 | |

| Amaricoccus | 0.850 | 0.0296 * | 0.61 | |

| Nordella | 0.846 | 0.0296 * | 0.38 | |

| Pseudonocardia | 0.830 | 0.0296 * | 0.35 | |

| Blastococcus | 0.823 | 0.0296 * | 0.83 | |

| Pedomicrobium | 0.815 | 0.0296 * | 0.63 | |

| Candidatus Alysiosphaera | 0.811 | 0.0296 * | 0.81 | |

| SWB02 | 0.808 | 0.0296 * | 0.45 | |

| Commercial purslane | Brevundimonas | 1.000 | 0.0296 * | 0.44 |

| Truepera | 1.000 | 0.0296 * | 0.05 | |

| Leptolyngbya EcFYyyy.00 | 0.991 | 0.0296 * | 0.004 | |

| Tychonema CCAP_1459.11B | 0.990 | 0.0296 * | 1.90 | |

| Lechevalieria | 0.975 | 0.0296 * | 2.89 | |

| Aeromicrobium | 0.958 | 0.0296 * | 0.68 | |

| Shinella | 0.929 | 0.0296 * | 0.70 | |

| Allorhizobium | 0.916 | 0.0296 * | 0.43 | |

| Aridibacter | 0.886 | 0.0296 * | 0.28 | |

| Streptomyces | 0.881 | 0.0296 * | 3.39 | |

| Nocardioides | 0.881 | 0.0296 * | 1.26 | |

| Herpetosiphon | 0.873 | 0.0296 * | 1.02 | |

| Altererythrobacter | 0.872 | 0.0296 * | 1.87 | |

| Pseudarthrobacter | 0.792 | 0.0296 * | 1.02 |

| Fungal Phyla | IndVal | p-Value | RA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish (wild) purslane | Rozellomycota | 0.860 | 0.0298 * | 1.45 |

| Commercial purslane | Mortierellomycota | 0.879 | 0.0298 * | 19.52 |

| Fungal genera | IndVal | p-value | RA (%) | |

| Spanish (wild) purslane | Byssochlamys | 1.000 | 0.0298 * | 0.06 |

| Metarhizium | 0.970 | 0.0298 * | 0.09 | |

| Wardomycopsis | 0.957 | 0.0298 * | 0.60 | |

| Aspergillus | 0.956 | 0.0298 * | 0.11 | |

| Liua | 0.950 | 0.0298 * | 1.23 | |

| Microascus | 0.947 | 0.0298 * | 0.61 | |

| Purpureocillium | 0.939 | 0.0298 * | 1.40 | |

| Auxarthron | 0.938 | 0.0298 * | 0.08 | |

| Stephanonectria | 0.936 | 0.0298 * | 0.06 | |

| Powellomyces | 0.935 | 0.0298 * | 0.44 | |

| Cladorrhinum | 0.933 | 0.0298 * | 0.51 | |

| Scopulariopsis | 0.930 | 0.0298 * | 0.14 | |

| Saksenaea | 0.898 | 0.0298 * | 0.14 | |

| Agaricus | 0.897 | 0.0298 * | 0.42 | |

| Chaetomium | 0.887 | 0.0298 * | 2.96 | |

| Naganishia | 0.868 | 0.0298 * | 1.89 | |

| Talaromyces | 0.865 | 0.0298 * | 0.08 | |

| Fusarium | 0.800 | 0.0298 * | 27.51 | |

| Commercial purslane | Lachancea | 1.000 | 0.0298 * | 0.02 |

| Gibberella | 0.996 | 0.0298 * | 1.12 | |

| Ulocladium | 0.988 | 0.0298 * | 5.57 | |

| Alternaria | 0.981 | 0.0298 * | 0.86 | |

| Chrysosporium | 0.915 | 0.0298 * | 3.73 | |

| Mortierella | 0.879 | 0.0298 * | 19.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrascosa, A.; Pascual, J.A.; López-García, A.; Romo-Vaquero, M.; Ros, M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Alguacil, M.d.M. Different Functional and Taxonomic Composition of the Microbiome in the Rhizosphere of Two Purslane Genotypes. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13071795

Carrascosa A, Pascual JA, López-García A, Romo-Vaquero M, Ros M, Petropoulos SA, Alguacil MdM. Different Functional and Taxonomic Composition of the Microbiome in the Rhizosphere of Two Purslane Genotypes. Agronomy. 2023; 13(7):1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13071795

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrascosa, Angel, Jose Antonio Pascual, Alvaro López-García, Maria Romo-Vaquero, Margarita Ros, Spyridon A. Petropoulos, and Maria del Mar Alguacil. 2023. "Different Functional and Taxonomic Composition of the Microbiome in the Rhizosphere of Two Purslane Genotypes" Agronomy 13, no. 7: 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13071795

APA StyleCarrascosa, A., Pascual, J. A., López-García, A., Romo-Vaquero, M., Ros, M., Petropoulos, S. A., & Alguacil, M. d. M. (2023). Different Functional and Taxonomic Composition of the Microbiome in the Rhizosphere of Two Purslane Genotypes. Agronomy, 13(7), 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13071795