The MAMs Structure and Its Role in Cell Death

Abstract

:1. Introduction

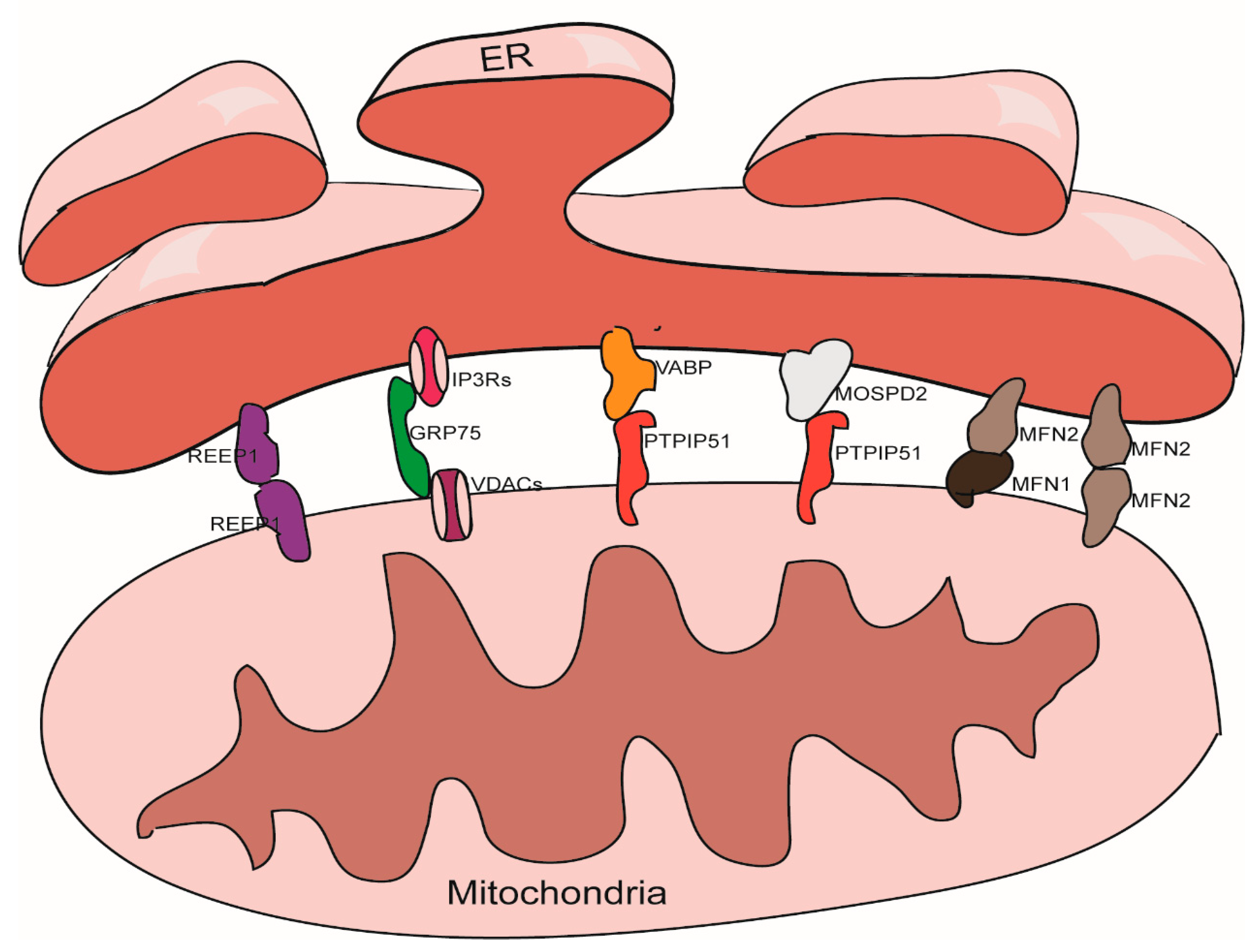

2. The Structural Characteristics of MAMs

3. The Structure Maintenance of MAMs

3.1. The IP3Rs-Grp75-VDACs Complex

3.2. The VAPB-PTPIP51 Complex

3.3. The Mfn1/Mfn2 Complex

3.4. The MOSPD2-PTPIP51 Complex

3.5. REEP1

3.6. Other Proteins Involved in MAMs Maintance

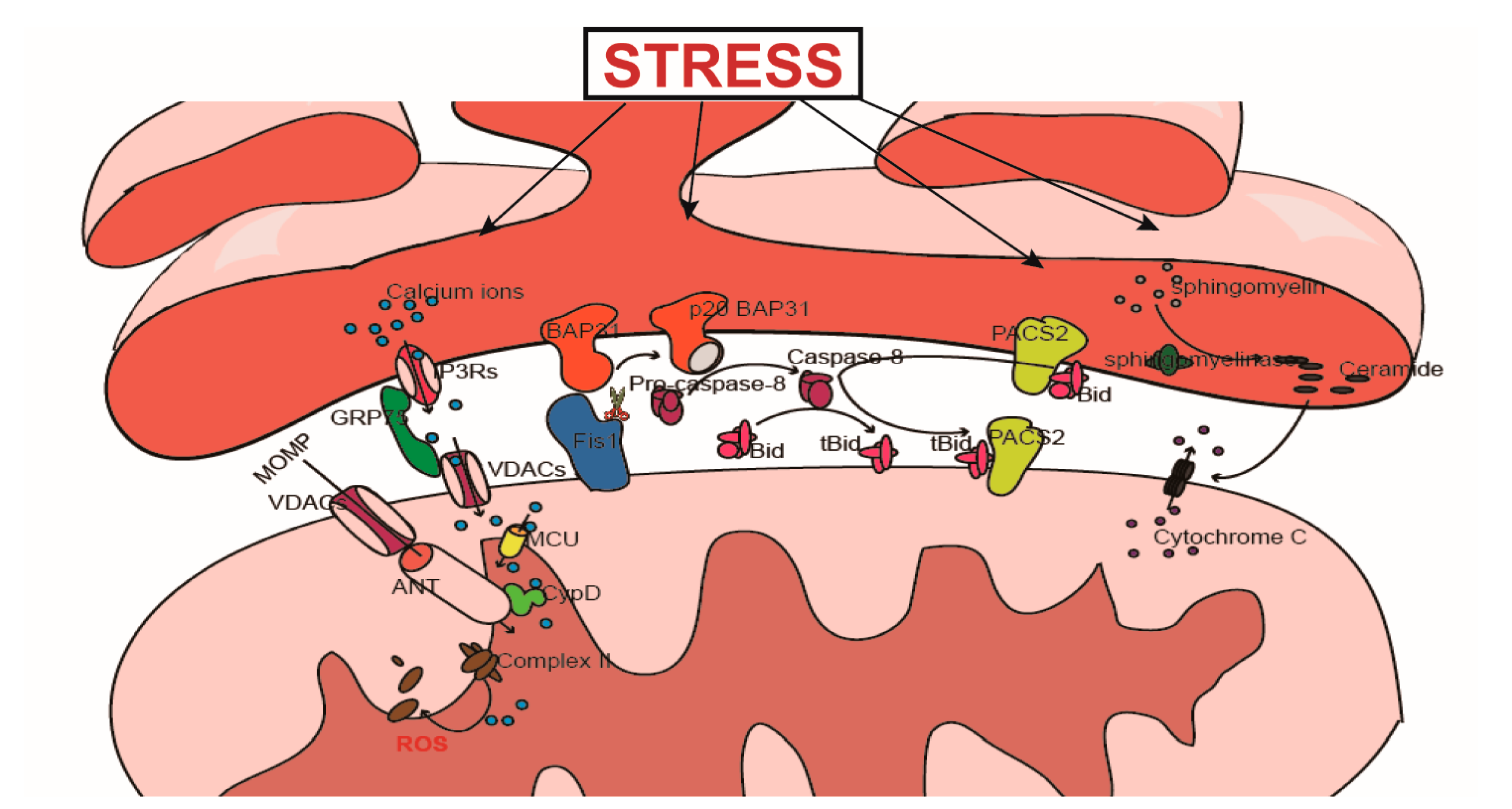

4. MAMs and Cell Death

4.1. Ca2+-Mediated Signal Transduction and Cell Death

4.1.1. The Physiological Role of Ca2+

4.1.2. The Regulatory Effect of MAMs on Ca2+ Transfer

The IP3Rs-Grp75-VDACs Complex

SERCAs

MCU

| Functions in MAMs | Proteins | Other Functions |

|---|---|---|

| α-Synuclein | Unknown | |

| CypD | Regulation of MPTP [121] | |

| DJ-1 | Antioxidant stress, chaperon activity, transcriptional regulation, degradation of proteins [122] | |

| FATE1 | Tolerance to cellular stress [123] | |

| FUNDC1 | Acts as mitophagy receptor [124] | |

| Structure maintenance | NogoB | Regulation of ER morphology [69] |

| PERK | Participating in ERS [125] | |

| PDK4 | Regulation of cellular metabolism and mitochondrial function [126] | |

| Presenilin-2 | Involved in cell adhesion, apoptosis and several cell-signaling processes [127] | |

| TDP-43 and FUS | RNA processing and transportation [128] | |

| TG2 | Modification of proteins [63] | |

| TpMs | Unknown | |

| Akt | Regulation of cell growth and differentiation [129] | |

| Bcl2 | Regulation of apoptosis [13] | |

| Bcl-xl | Regulation of apoptosis [13] | |

| Bok | Regulation of apoptosis and mitochondrial fusion/fission [130] | |

| BRCA1 | A tumor suppressor, repair of DNA damage [107,131] | |

| Caveolin-1 | Participating in the regulation of the cell cycle and cellular senescence, proliferation and invasion, cell death as well as membrane composition, lipid homeostasis and metabolism [132] | |

| ERO1α | Protein folding [133] | |

| MCL1 | Regulation of apoptosis [13] | |

| Regulating function of IP3Rs | mTORC2 | Participating in multiple cellular processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation [134] |

| NCS1 and WFS1 | Contributing to the maintenance of intracellular calcium homeostasis and regulation of calcium-dependent signaling pathways [135]; regulation of ER stress signaling [108] | |

| PML | Functions as a tumor suppressor and also involved in multiple cellular activities [136] | |

| PTEN | Tumor suppressor and metabolic regulator [137] | |

| Ras | Participating in proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, senescence, and metabolism [138] | |

| Sig1-R | Regulation of ER stress, function of mitochondria, and oxidative stress, etc., [139] | |

| Tespa1 | signaling molecule in thymocyte development [140] | |

| Bcl2 | Regulation of apoptosis [13] | |

| CHOP | Participating in ER stress and apoptosis regulation [141] | |

| Regulating function of SERCAs | ERO1α and SEPN1 | Regulation of protein folding and secretion and inhibiting apoptosis, and regulates tumor progression [142]; regulation of oxidative stress [143] |

| P53 | Multiple roles in cellular activities [144] | |

| PMX1 | Participating in protein folding [116,145] | |

| S1Ts | Variants of SERCA1 [119,120] |

4.2. PACS2 Participates in the Transduction of Apoptosis Signals from the ER to the Mitochondria

4.3. The Role of LIPID Metabolism in the Transduction of Apoptosis Signals

4.4. The Fis1-BAP31 Complex Is Involved in the Transduction of Apoptosis Signals

4.4.1. The Relationship between Fis1 and Apoptosis

4.4.2. Fis1-BAP31 Participates in Apoptosis Signal Transduction from the Mitochondria to the ER

5. Methods of Detection

5.1. Fluorescence Microscopy

5.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

5.3. Gradient Centrifugation

5.4. The Functional Evaluation of MAMs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACAT1/SOAT1 | Acyl-Coenzyme A: Cholesterol Acyltransferase-1 |

| ACS | Fatty acid CoA ligase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AIF | Apoptosis inducing factor |

| Akt | Serine/threonine-protein kinases |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| ATAD3A | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3A |

| ATF4 | Activating Transcription Factor 4 |

| BAP31 | B-cell receptor associated protein 31 |

| Bip | Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein |

| BRCA1 | Breast cancer susceptibility gene |

| CypD | Cyclophilin D |

| IRE1 | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| eIF2α | eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2α |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERO1α | Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1-α |

| ERS | Endoplasmic reticulum stress |

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| FADD | Fas-associating protein with a novel death domain |

| FasL | Fas ligand |

| FATE1 | Fetal and adult testis expressed 1 |

| Fis1 | Mitochondrial fission 1 |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| FUNDC1 | FUN14 domain containing 1 |

| FUS | Fused in sarcoma |

| Grp75 | 75 KDa Glucose-regulated protein |

| GSK-3b | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| IP3Rs | Inositol1,4,5-trisphosphatereceptors |

| MAMs | Mitochondria associated membranes |

| MCU | Mitochondrial Ca(2+) uniporter |

| Mfn1/2 | Mitofusins 1/2 |

| MOSPD2 | Motile sperm domain-containing protein 2 |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| mTORC2 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex2 |

| NCS1 | Nucleobase cation symporter-1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| PACS2 | Phosphoacidic cluster sorting protein 2 |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PDK4 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 |

| PERK | Protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PTPIP51 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase interacting protein 51 |

| REEP1 | Receptor expression-enhancing protein 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RyRs | Ryanodine receptors |

| SEPN1 | Selenoprotein N |

| SERCAs | Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium-ATPases |

| Sig-R | ECF sigma factor sigma(R) |

| S1Ts | Exon 4 and/or exon 11 spliced SERCA1 splice variants |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA binding protein 43 |

| TG2 | Transglutaminase 2 |

| TMX1 | Transmembrane thioredoxin-related protein 1 |

| TNFR1 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 |

| TpMs | Trichoplein keratin filament binding protein |

| TRADD | TNF receptor-associated death domain |

| VABP | Vitamin A binding protein |

| VDAC | Voltage-dependent anion channel |

| WASF3 | Wiskott-Aldridge syndrome family 3 |

| WFS1 | Wolfram syndrome type 1 |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1 |

References

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, R.; Sinibaldi, F.; Cozza, P.; Polticelli, F.; Fiorucci, L. Cytochrome c: An extreme multifunctional protein with a key role in cell fate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 136, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korga, A.; Korobowicz, E.; Dudka, J. Role of mitochondrial protein Smac/Diablo in regulation of apoptotic pathways. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski 2006, 20, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vande Walle, L.; Lamkanfi, M.; Vandenabeele, P. The mitochondrial serine protease HtrA2/Omi: An overview. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bano, D.; Prehn, J.H.M. Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) in Physiology and Disease: The Tale of a Repented Natural Born Killer. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Low, R.L. Mitochondrial Endonuclease G function in apoptosis and mtDNA metabolism: A historical perspective. Mitochondrion 2003, 2, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.D.; Sorensen, C.S. The caspase-activated DNase: Apoptosis and beyond. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcy, M.S. Cell death: A review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantari, C.; Walczak, H. Caspase-8 and bid: Caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, J.; O’Neill, K.L.; Gurumurthy, C.B.; Quadros, R.M.; Tu, Y.; Luo, X. Cleavage by Caspase 8 and Mitochondrial Membrane Association Activate the BH3-only Protein Bid during TRAIL-induced Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 11843–11851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voskoboinik, I.; Whisstock, J.C.; Trapani, J.A. Perforin and granzymes: Function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Watari, H.; AbuAlmaaty, A.; Ohba, Y.; Sakuragi, N. Apoptosis and molecular targeting therapy in cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 150845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siddiqui, W.A.; Ahad, A.; Ahsan, H. The mystery of BCL2 family: Bcl-2 proteins and apoptosis: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rafiuddin-Shah, M.; Tu, H.C.; Jeffers, J.R.; Zambetti, G.P.; Hsieh, J.J.; Cheng, E.H. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1348–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.S.; Blower, M.D. The endoplasmic reticulum: Structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braakman, I.; Hebert, D.N. Protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a013201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quon, E.; Sere, Y.Y.; Chauhan, N.; Johansen, J.; Sullivan, D.P.; Dittman, J.S.; Rice, W.J.; Chan, R.B.; Di Paolo, G.; Beh, C.T.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites integrate sterol and phospholipid regulation. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.S. Calcium Signaling: From Basic to Bedside. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1131, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesley, S.J.; Fisher, P.R. Mitochondria in Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Desagher, S.; Martinou, J.C. Mitochondria as the central control point of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Trojel-Hansen, C.; Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doghman-Bouguerra, M.; Lalli, E. ER-mitochondria interactions: Both strength and weakness within cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Rouiller, C. Close topographical relationship between mitochondria and ergastoplasm of liver cells in a definite phase of cellular activity. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1956, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannella, C.A. The relevance of mitochondrial membrane topology to mitochondrial function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rizzuto, R.; Pinton, P.; Carrington, W.; Fay, F.S.; Fogarty, K.E.; Lifshitz, L.M.; Tuft, R.A.; Pozzan, T. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science 1998, 280, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Missiroli, S.; Morciano, G.; Rimessi, A.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and cell death. Cell Calcium 2018, 69, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurlaro, R.; Munoz-Pinedo, C. Cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 2640–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardner, B.M.; Pincus, D.; Gotthardt, K.; Gallagher, C.M.; Walter, P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a013169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giacomello, M.; Pellegrini, L. The coming of age of the mitochondria-ER contact: A matter of thickness. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filadi, R.; Theurey, P.; Pizzo, P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease: Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium 2017, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordas, G.; Renken, C.; Varnai, P.; Walter, L.; Weaver, D.; Buttle, K.F.; Balla, T.; Mannella, C.A.; Hajnoczky, G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, A.; Williamson, C.D.; Wong, D.S.; Bullough, M.D.; Brown, K.J.; Hathout, Y.; Colberg-Poley, A.M. Quantitative proteomic analyses of human cytomegalovirus-induced restructuring of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts at late times of infection. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011, 10, M111-009936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poston, C.N.; Krishnan, S.C.; Bazemore-Walker, C.R. In-depth proteomic analysis of mammalian mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM). J. Proteom. 2013, 79, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janikiewicz, J.; Szymanski, J.; Malinska, D.; Patalas-Krawczyk, P.; Michalska, B.; Duszynski, J.; Giorgi, C.; Bonora, M.; Dobrzyn, A.; Wieckowski, M.R. Mitochondria-associated membranes in aging and senescence: Structure, function, and dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parys, J.B.; Vervliet, T. New Insights in the IP3 Receptor and Its Regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1131, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Nishizawa, M.; Onodera, O. Roles of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in spinocerebellar ataxias. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazure, N.M. VDAC in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabadkai, G.; Bianchi, K.; Varnai, P.; De Stefani, D.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Cavagna, D.; Nagy, A.I.; Balla, T.; Rizzuto, R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 175, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rapizzi, E.; Pinton, P.; Szabadkai, G.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Vandecasteele, G.; Baird, G.; Tuft, R.A.; Fogarty, K.E.; Rizzuto, R. Recombinant expression of the voltage-dependent anion channel enhances the transfer of Ca2+ microdomains to mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 159, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tubbs, E.; Theurey, P.; Vial, G.; Bendridi, N.; Bravard, A.; Chauvin, M.A.; Ji-Cao, J.; Zoulim, F.; Bartosch, B.; Ovize, M.; et al. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) integrity is required for insulin signaling and is implicated in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3279–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Honrath, B.; Metz, I.; Bendridi, N.; Rieusset, J.; Culmsee, C.; Dolga, A.M. Glucose-regulated protein 75 determines ER-mitochondrial coupling and sensitivity to oxidative stress in neuronal cells. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thoudam, T.; Ha, C.M.; Leem, J.; Chanda, D.; Park, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, J.H.; Choi, Y.K.; Liangpunsakul, S.; Huh, Y.H.; et al. PDK4 Augments ER-Mitochondria Contact to Dampen Skeletal Muscle Insulin Signaling during Obesity. Diabetes 2019, 68, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinay Kumar, C.; Kumar, K.M.; Swetha, R.; Ramaiah, S.; Anbarasu, A. Protein aggregation due to nsSNP resulting in P56S VABP protein is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 354, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekura, K.; Nishimoto, I.; Aiso, S.; Matsuoka, M. Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked P56S mutation of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB/ALS8). J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 30223–30233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vos, K.J.; Morotz, G.M.; Stoica, R.; Tudor, E.L.; Lau, K.F.; Ackerley, S.; Warley, A.; Shaw, C.E.; Miller, C.C. VAPB interacts with the mitochondrial protein PTPIP51 to regulate calcium homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoica, R.; De Vos, K.J.; Paillusson, S.; Mueller, S.; Sancho, R.M.; Lau, K.F.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Lin, W.L.; Xu, Y.F.; Lewis, J.; et al. ER-mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTD-associated TDP-43. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qiao, X.; Jia, S.; Ye, J.; Fang, X.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. PTPIP51 regulates mouse cardiac ischemia/reperfusion through mediating the mitochondria-SR junction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formosa, L.E.; Ryan, M.T. Mitochondrial fusion: Reaching the end of mitofusin’s tether. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Brito, O.M.; Scorrano, L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 2008, 456, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alford, S.C.; Ding, Y.; Simmen, T.; Campbell, R.E. Dimerization-dependent green and yellow fluorescent proteins. ACS Synth. Biol. 2012, 1, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naon, D.; Zaninello, M.; Giacomello, M.; Varanita, T.; Grespi, F.; Lakshminaranayan, S.; Serafini, A.; Semenzato, M.; Herkenne, S.; Hernandez-Alvarez, M.I.; et al. Critical reappraisal confirms that Mitofusin 2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tether. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11249–11254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cosson, P.; Marchetti, A.; Ravazzola, M.; Orci, L. Mitofusin-2 independent juxtaposition of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria: An ultrastructural study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2174–E2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herrera-Cruz, M.S.; Simmen, T. Cancer: Untethering Mitochondria from the Endoplasmic Reticulum? Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Mattia, T.; Wilhelm, L.P.; Ikhlef, S.; Wendling, C.; Spehner, D.; Nomine, Y.; Giordano, F.; Mathelin, C.; Drin, G.; Tomasetto, C.; et al. Identification of MOSPD2, a novel scaffold for endoplasmic reticulum membrane contact sites. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Cho, I.T.; Schoel, L.J.; Cho, G.; Golden, J.A. Hereditary spastic paraplegia-linked REEP1 modulates endoplasmic reticulum/mitochondria contacts. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 78, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Area-Gomez, E.; Rub, C.; Liu, Y.; Magrane, J.; Becker, D.; Voos, W.; Schon, E.A.; Przedborski, S. alpha-Synuclein is localized to mitochondria-associated ER membranes. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cali, T.; Ottolini, D.; Negro, A.; Brini, M. alpha-Synuclein controls mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17914–17929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gomez-Suaga, P.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Gonzalez-Polo, R.A.; Fuentes, J.M.; Niso-Santano, M. ER-mitochondria signaling in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ottolini, D.; Cali, T.; Negro, A.; Brini, M. The Parkinson disease-related protein DJ-1 counteracts mitochondrial impairment induced by the tumour suppressor protein p53 by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 2152–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Fujioka, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, X. DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 25322–25328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, R.; Paillusson, S.; Gomez-Suaga, P.; Mitchell, J.C.; Lau, D.H.; Gray, E.H.; Sancho, R.M.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; De Vos, K.J.; Shaw, C.E.; et al. ALS/FTD-associated FUS activates GSK-3beta to disrupt the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and ER-mitochondria associations. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eletto, M.; Rossin, F.; Occhigrossi, L.; Farrace, M.G.; Faccenda, D.; Desai, R.; Marchi, S.; Refolo, G.; Falasca, L.; Antonioli, M.; et al. Transglutaminase Type 2 Regulates ER-Mitochondria Contact Sites by Interacting with GRP75. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 3573–3581 e3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerqua, C.; Anesti, V.; Pyakurel, A.; Liu, D.; Naon, D.; Wiche, G.; Baffa, R.; Dimmer, K.S.; Scorrano, L. Trichoplein/mitostatin regulates endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria juxtaposition. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillard, M.; Tubbs, E.; Thiebaut, P.A.; Gomez, L.; Fauconnier, J.; Da Silva, C.C.; Teixeira, G.; Mewton, N.; Belaidi, E.; Durand, A.; et al. Depressing mitochondria-reticulum interactions protects cardiomyocytes from lethal hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Circulation 2013, 128, 1555–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Ma, Z.; Mao, X.; Huang, K.; Xie, Z.; Zou, M.H. Binding of FUN14 Domain Containing 1 With Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor in Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes Maintains Mitochondrial Dynamics and Function in Hearts In Vivo. Circulation 2017, 136, 2248–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Presenilin 2 Modulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Coupling by Tuning the Antagonistic Effect of Mitofusin 2. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doghman-Bouguerra, M.; Granatiero, V.; Sbiera, S.; Sbiera, I.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Brau, F.; Fassnacht, M.; Rizzuto, R.; Lalli, E. FATE1 antagonizes calcium- and drug-induced apoptosis by uncoupling ER and mitochondria. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutendra, G.; Dromparis, P.; Wright, P.; Bonnet, S.; Haromy, A.; Hao, Z.; McMurtry, M.S.; Michalak, M.; Vance, J.E.; Sessa, W.C.; et al. The role of Nogo and the mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum unit in pulmonary hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 88ra55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munoz, J.P.; Ivanova, S.; Sanchez-Wandelmer, J.; Martinez-Cristobal, P.; Noguera, E.; Sancho, A.; Diaz-Ramos, A.; Hernandez-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastian, D.; Mauvezin, C.; et al. Mfn2 modulates the UPR and mitochondrial function via repression of PERK. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 2348–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Vliet, A.R.; Agostinis, P. When under pressure, get closer: PERKing up membrane contact sites during ER stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeresh, P.; Kaur, H.; Sarmah, D.; Mounica, L.; Verma, G.; Kotian, V.; Kesharwani, R.; Kalia, K.; Borah, A.; Wang, X.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria crosstalk: From junction to function across neurological disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Sagua, R.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Kuzmicic, J.; Gutierrez, T.; Lopez-Crisosto, C.; Quiroga, C.; Diaz-Elizondo, J.; Chiong, M.; Gillette, T.G.; Rothermel, B.A.; et al. Cell death and survival through the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial axis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chami, M.; Checler, F. Alterations of the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Calcium Signaling Molecular Components in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, H.; Vervliet, T.; Missiaen, L.; Parys, J.B.; De Smedt, H.; Bultynck, G. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-isoform diversity in cell death and survival. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2164–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rizzuto, R.; Simpson, A.W.; Brini, M.; Pozzan, T. Rapid changes of mitochondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature 1992, 358, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomello, M.; Drago, I.; Bortolozzi, M.; Scorzeto, M.; Gianelle, A.; Pizzo, P.; Pozzan, T. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasen, J.C.; Olsen, L.F.; Hallett, M.B. Cell surface topology creates high Ca2+ signalling microdomains. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Dubinin, M.V.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Mironova, G.D. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Transport: Mechanisms, Molecular Structures, and Role in Cells. Biochemistry 2019, 84, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Territo, P.R.; Mootha, V.K.; French, S.A.; Balaban, R.S. Ca2+ activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: Role of the F0/F1-ATPase. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000, 278, C423–C435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glancy, B.; Willis, W.T.; Chess, D.J.; Balaban, R.S. Effect of calcium on the oxidative phosphorylation cascade in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2793–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitani, Y.; Behrooz, A.; Dubyak, G.R.; Ismail-Beigi, F. Stimulation of GLUT-1 glucose transporter expression in response to exposure to calcium ionophore A-23187. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 269, C1228–C1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Baldassari, F.; Bononi, A.; Bonora, M.; De Marchi, E.; Marchi, S.; Missiroli, S.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; Suski, J.M.; et al. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and apoptosis. Cell Calcium 2012, 52, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinton, P.; Ferrari, D.; Rapizzi, E.; Di Virgilio, F.; Pozzan, T.; Rizzuto, R. The Ca2+ concentration of the endoplasmic reticulum is a key determinant of ceramide-induced apoptosis: Significance for the molecular mechanism of Bcl-2 action. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2690–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, M.; Jones, K.; Sartori, G.; Schiavone, M.; Antonucci, S.; Kucharczyk, R.; di Rago, J.P.; Franchin, C.; Arrigoni, G.; Forte, M.; et al. The Unique Cysteine of F-ATP Synthase OSCP Subunit Participates in Modulation of the Permeability Transition Pore. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, M.S.; Schwall, C.T.; Pazarentzos, E.; Datler, C.; Alder, N.N.; Grimm, S. Mitochondrial Ca2+ influx targets cardiolipin to disintegrate respiratory chain complex II for cell death induction. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchi, S.; Marinello, M.; Bononi, A.; Bonora, M.; Giorgi, C.; Rimessi, A.; Pinton, P. Selective modulation of subtype III IP3R by Akt regulates ER Ca2+ release and apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Szado, T.; Vanderheyden, V.; Parys, J.B.; De Smedt, H.; Rietdorf, K.; Kotelevets, L.; Chastre, E.; Khan, F.; Landegren, U.; Soderberg, O.; et al. Phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by protein kinase B/Akt inhibits Ca2+ release and apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2427–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marchi, S.; Rimessi, A.; Giorgi, C.; Baldini, C.; Ferroni, L.; Rizzuto, R.; Pinton, P. Akt kinase reducing endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release protects cells from Ca2+-dependent apoptotic stimuli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 375, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Betz, C.; Stracka, D.; Prescianotto-Baschong, C.; Frieden, M.; Demaurex, N.; Hall, M.N. Feature Article: mTOR complex 2-Akt signaling at mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) regulates mitochondrial physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12526–12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagiwara, A.; Cornu, M.; Cybulski, N.; Polak, P.; Betz, C.; Trapani, F.; Terracciano, L.; Heim, M.H.; Ruegg, M.A.; Hall, M.N. Hepatic mTORC2 activates glycolysis and lipogenesis through Akt, glucokinase, and SREBP1c. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, C.; Ito, K.; Lin, H.K.; Santangelo, C.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Lebiedzinska, M.; Bononi, A.; Bonora, M.; Duszynski, J.; Bernardi, R.; et al. PML regulates apoptosis at endoplasmic reticulum by modulating calcium release. Science 2010, 330, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bononi, A.; Bonora, M.; Marchi, S.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; Giorgi, C.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Pinton, P. Identification of PTEN at the ER and MAMs and its regulation of Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in a protein phosphatase-dependent manner. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monaco, G.; Decrock, E.; Akl, H.; Ponsaerts, R.; Vervliet, T.; Luyten, T.; De Maeyer, M.; Missiaen, L.; Distelhorst, C.W.; De Smedt, H.; et al. Selective regulation of IP3-receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis by the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 versus Bcl-Xl. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbel, N.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1-based peptides interact with Bcl-2 to prevent antiapoptotic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 6053–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eckenrode, E.F.; Yang, J.; Velmurugan, G.V.; Foskett, J.K.; White, C. Apoptosis protection by Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 modulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13678–13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Shah, K.; Bradbury, N.A.; Li, C.; White, C. Mcl-1 promotes lung cancer cell migration by directly interacting with VDAC to increase mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and reactive oxygen species generation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schulman, J.J.; Wright, F.A.; Kaufmann, T.; Wojcikiewicz, R.J. The Bcl-2 protein family member Bok binds to the coupling domain of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and protects them from proteolytic cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25340–25349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assefa, Z.; Bultynck, G.; Szlufcik, K.; Nadif Kasri, N.; Vermassen, E.; Goris, J.; Missiaen, L.; Callewaert, G.; Parys, J.B.; De Smedt, H. Caspase-3-induced truncation of type 1 inositol trisphosphate receptor accelerates apoptotic cell death and induces inositol trisphosphate-independent calcium release during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 43227–43236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, A.; Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P.; Betenbaugh, M.J. Bcl-2 family in inter-organelle modulation of calcium signaling; roles in bioenergetics and cell survival. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2014, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, L.; Niu, F.; Liao, K.; Buch, S. Role of Sigma-1 Receptor in Cocaine Abuse and Neurodegenerative Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 964, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca2+ signaling and cell survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raggi, C.; Diociaiuti, M.; Caracciolo, G.; Fratini, F.; Fantozzi, L.; Piccaro, G.; Fecchi, K.; Pizzi, E.; Marano, G.; Ciaffoni, F.; et al. Caveolin-1 Endows Order in Cholesterol-Rich Detergent Resistant Membranes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sundivakkam, P.C.; Kwiatek, A.M.; Sharma, T.T.; Minshall, R.D.; Malik, A.B.; Tiruppathi, C. Caveolin-1 scaffold domain interacts with TRPC1 and IP3R3 to regulate Ca2+ store release-induced Ca2+ entry in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C403–C413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rimessi, A.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Pinton, P. H-Ras-driven tumoral maintenance is sustained through caveolin-1-dependent alterations in calcium signaling. Oncogene 2014, 33, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedgepeth, S.C.; Garcia, M.I.; Wagner, L.E., 2nd; Rodriguez, A.M.; Chintapalli, S.V.; Snyder, R.R.; Hankins, G.D.; Henderson, B.R.; Brodie, K.M.; Yule, D.I.; et al. The BRCA1 tumor suppressor binds to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors to stimulate apoptotic calcium release. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 7304–7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Angebault, C.; Fauconnier, J.; Patergnani, S.; Rieusset, J.; Danese, A.; Affortit, C.A.; Jagodzinska, J.; Megy, C.; Quiles, M.; Cazevieille, C.; et al. ER-mitochondria cross-talk is regulated by the Ca2+ sensor NCS1 and is impaired in Wolfram syndrome. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delprat, B.; Maurice, T.; Delettre, C. Wolfram syndrome: MAMs’ connection? Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Fujimoto, T.; Ota, T.; Ogawa, M.; Tsunoda, T.; Doi, K.; Hamabashiri, M.; Tanaka, M.; Shirasawa, S. Tespa1 is a novel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding protein in T and B lymphocytes. FEBS Open Bio 2012, 2, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Fujimoto, T.; Tanaka, M.; Shirasawa, S. Tespa1 is a novel component of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes and affects mitochondrial calcium flux. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 433, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Mongillo, M.; Chin, K.T.; Harding, H.; Ron, D.; Marks, A.R.; Tabas, I. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, C.; Bonora, M.; Sorrentino, G.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; Suski, J.M.; Galindo Ramirez, F.; Rizzuto, R.; Di Virgilio, F.; Zito, E.; et al. p53 at the endoplasmic reticulum regulates apoptosis in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, C.; Bonora, M.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; Ramirez, F.G.; Morciano, G.; Morganti, C.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Mammano, F.; Pinton, P. Intravital imaging reveals p53-dependent cancer cell death induced by phototherapy via calcium signaling. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krols, M.; Bultynck, G.; Janssens, S. ER-Mitochondria contact sites: A new regulator of cellular calcium flux comes into play. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 214, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raturi, A.; Gutierrez, T.; Ortiz-Sandoval, C.; Ruangkittisakul, A.; Herrera-Cruz, M.S.; Rockley, J.P.; Gesson, K.; Ourdev, D.; Lou, P.H.; Lucchinetti, E.; et al. TMX1 determines cancer cell metabolism as a thiol-based modulator of ER-mitochondria Ca2+ flux. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 214, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dremina, E.S.; Sharov, V.S.; Kumar, K.; Zaidi, A.; Michaelis, E.K.; Schoneich, C. Anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 interacts with and destabilizes the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). Biochem. J. 2004, 383, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marino, M.; Stoilova, T.; Giorgi, C.; Bachi, A.; Cattaneo, A.; Auricchio, A.; Pinton, P.; Zito, E. SEPN1, an endoplasmic reticulum-localized selenoprotein linked to skeletal muscle pathology, counteracts hyperoxidation by means of redox-regulating SERCA2 pump activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chami, M.; Gozuacik, D.; Lagorce, D.; Brini, M.; Falson, P.; Peaucellier, G.; Pinton, P.; Lecoeur, H.; Gougeon, M.L.; le Maire, M.; et al. SERCA1 truncated proteins unable to pump calcium reduce the endoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration and induce apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chami, M.; Oules, B.; Szabadkai, G.; Tacine, R.; Rizzuto, R.; Paterlini-Brechot, P. Role of SERCA1 truncated isoform in the proapoptotic calcium transfer from ER to mitochondria during ER stress. Mol. Cell 2008, 32, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fayaz, S.M.; Raj, Y.V.; Krishnamurthy, R.G. CypD: The Key to the Death Door. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijioka, M.; Inden, M.; Yanagisawa, D.; Kitamura, Y. DJ-1/PARK7: A New Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maxfield, K.E.; Taus, P.J.; Corcoran, K.; Wooten, J.; Macion, J.; Zhou, Y.; Borromeo, M.; Kollipara, R.K.; Yan, J.; Xie, Y.; et al. Comprehensive functional characterization of cancer-testis antigens defines obligate participation in multiple hallmarks of cancer. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Chen, L.; Gao, R.; Liu, L.; et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy 2016, 12, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohno, M. PERK as a hub of multiple pathogenic pathways leading to memory deficits and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 141, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.; Lee, I.K. Mechanisms of Vascular Calcification: The Pivotal Role of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 31, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Schubert, D. Presenilin-interacting proteins. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2002, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, A.; Buratti, E. Physiological functions and pathobiology of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS proteins. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138 (Suppl. 1), 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathidevi, S.; Munirajan, A.K. Akt in cancer: Mediator and more. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 59, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.J.; Szczesniak, L.M.; Bunker, E.N.; Nelson, H.A.; Roe, M.W.; Wagner, L.E., 2nd; Yule, D.I.; Wojcikiewicz, R.J.H. Bok regulates mitochondrial fusion and morphology. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 2682–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Snyder, R.R.; Hankins, G.D.; Boehning, D. Structure-Function Of The Tumor Suppressor BRCA1. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ketteler, J.; Klein, D. Caveolin-1, cancer and therapy resistance. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2092–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shergalis, A.G.; Hu, S.; Bankhead, A., 3rd; Neamati, N. Role of the ERO1-PDI interaction in oxidative protein folding and disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 210, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, T.; Lupse, B.; Maedler, K.; Ardestani, A. mTORC2 Signaling: A Path for Pancreatic beta Cell’s Growth and Function. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 904–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckel, G.R.; Ehrlich, B.E. NCS-1 is a regulator of calcium signaling in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.S.; Kao, H.Y. PML: Regulation and multifaceted function beyond tumor suppression. Cell Biosci. 2018, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Stiles, B.L. PTEN: Tumor Suppressor and Metabolic Regulator. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slack, C. Ras signaling in aging and metabolic regulation. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2017, 4, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Penke, B.; Fulop, L.; Szucs, M.; Frecska, E. The Role of Sigma-1 Receptor, an Intracellular Chaperone in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, M.; Lei, L.; Ji, J.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, L.; Lou, J.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Tespa1 is involved in late thymocyte development through the regulation of TCR-mediated signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tang, J.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Z. New insights into the roles of CHOP-induced apoptosis in ER stress. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2014, 46, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, J.; Jin, J.; Qu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F. ERO1alpha inhibits cell apoptosis and regulates steroidogenesis in mouse granulosa cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 511, 110842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzer, D.; Varone, E.; Chernorudskiy, A.; Schiarea, S.; Missiroli, S.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P.; Canato, M.; Germinario, E.; Nogara, L.; et al. A maladaptive ER stress response triggers dysfunction in highly active muscles of mice with SELENON loss. Redox Biol. 2019, 20, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptenko, O.; Prives, C. p53: Master of life, death, and the epigenome. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 955–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y.; Hirota, K. Transmembrane thioredoxin-related protein TMX1 is reversibly oxidized in response to protein accumulation in the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Open Bio 2017, 7, 1768–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, T.M.; Kim, J.H.; Granger, D.A.; Vance, J.E.; Coleman, R.A. Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 1, 4, and 5 are present in different subcellular membranes in rat liver and can be inhibited independently. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 24674–24679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rusinol, A.E.; Cui, Z.; Chen, M.H.; Vance, J.E. A unique mitochondria-associated membrane fraction from rat liver has a high capacity for lipid synthesis and contains pre-Golgi secretory proteins including nascent lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 27494–27502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, I.C.M.; Morciano, G.; Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska, M.; Aguiari, G.; Pinton, P.; Potes, Y.; Wieckowski, M.R. The mystery of mitochondria-ER contact sites in physiology and pathology: A cancer perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, T.D.; Obeid, L.M. Ceramide and apoptosis: Exploring the enigmatic connections between sphingolipid metabolism and programmed cell death. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalfant, C.E.; Szulc, Z.; Roddy, P.; Bielawska, A.; Hannun, Y.A. The structural requirements for ceramide activation of serine-threonine protein phosphatases. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, J.; Berra, E.; Municio, M.M.; Diaz-Meco, M.T.; Dominguez, I.; Sanz, L.; Moscat, J. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for kappa B-dependent promoter activation by sphingomyelinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19200–19202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, B.; Delikat, S.; Bayoumy, S.; Lin, X.H.; Basu, S.; McGinley, M.; Chan-Hui, P.Y.; Lichenstein, H.; Kolesnick, R. Kinase suppressor of Ras is ceramide-activated protein kinase. Cell 1997, 89, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saddoughi, S.A.; Ogretmen, B. Diverse functions of ceramide in cancer cell death and proliferation. Adv. Cancer Res. 2013, 117, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Freter, C. Lipid metabolism, apoptosis and cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 924–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stiban, J.; Caputo, L.; Colombini, M. Ceramide synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum can permeabilize mitochondria to proapoptotic proteins. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siskind, L.J.; Kolesnick, R.N.; Colombini, M. Ceramide channels increase the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane to small proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 26796–26803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coleman, R.A.; Lewin, T.M.; Van Horn, C.G.; Gonzalez-Baro, M.R. Do long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases regulate fatty acid entry into synthetic versus degradative pathways? J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2123–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Karbowski, M.; Smith, C.L.; Youle, R.J. Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5001–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alirol, E.; James, D.; Huber, D.; Marchetto, A.; Vergani, L.; Martinou, J.C.; Scorrano, L. The mitochondrial fission protein hFis1 requires the endoplasmic reticulum gateway to induce apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 4593–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, T.; Fox, R.J.; Burwell, L.S.; Yoon, Y. Regulation of mitochondrial fission and apoptosis by the mitochondrial outer membrane protein hFis1. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 4141–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnoult, D.; Grodet, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Estaquier, J.; Blackstone, C. Release of OPA1 during apoptosis participates in the rapid and complete release of cytochrome c and subsequent mitochondrial fragmentation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 35742–35750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, W.; Pu, Y.; Luo, K.Q.; Chang, D.C. Temporal relationship between cytochrome c release and mitochondrial swelling during UV-induced apoptosis in living HeLa cells. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iwasawa, R.; Mahul-Mellier, A.L.; Datler, C.; Pazarentzos, E.; Grimm, S. Fis1 and Bap31 bridge the mitochondria-ER interface to establish a platform for apoptosis induction. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Area-Gomez, E.; Schon, E.A. On the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: The MAM Hypothesis. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Nguyen, M.; Chang, N.C.; Shore, G.C. Fis1, Bap31 and the kiss of death between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sivaguru, M.; Urban, M.A.; Fried, G.; Wesseln, C.J.; Mander, L.; Punyasena, S.W. Comparative performance of airyscan and structured illumination superresolution microscopy in the study of the surface texture and 3D shape of pollen. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2018, 81, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elgass, K.D.; Smith, E.A.; LeGros, M.A.; Larabell, C.A.; Ryan, M.T. Analysis of ER-mitochondria contacts using correlative fluorescence microscopy and soft X-ray tomography of mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2795–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csordas, G.; Weaver, D.; Hajnoczky, G. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Contactology: Structure and Signaling Functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Lackner, L.L.; West, M.; DiBenedetto, J.R.; Nunnari, J.; Voeltz, G.K. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science 2011, 334, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murley, A.; Lackner, L.L.; Osman, C.; West, M.; Voeltz, G.K.; Walter, P.; Nunnari, J. ER-associated mitochondrial division links the distribution of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in yeast. eLife 2013, 2, e00422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Whiteus, C.; Xu, C.S.; Hayworth, K.J.; Weinberg, R.J.; Hess, H.F.; De Camilli, P. Contacts between the endoplasmic reticulum and other membranes in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4859–E4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Chen, Y.; Miao, G.; Zhao, H.; Qu, W.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; et al. The ER-Localized Transmembrane Protein EPG-3/VMP1 Regulates SERCA Activity to Control ER-Isolation Membrane Contacts for Autophagosome Formation. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 974–989.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williamson, C.D.; Wong, D.S.; Bozidis, P.; Zhang, A.; Colberg-Poley, A.M. Isolation of Endoplasmic Reticulum, Mitochondria, and Mitochondria-Associated Membrane and Detergent Resistant Membrane Fractions from Transfected Cells and from Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Primary Fibroblasts. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2015, 68, 3.27.1–3.27.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, I.T.; Adelmant, G.; Lim, Y.; Marto, J.A.; Cho, G.; Golden, J.A. Ascorbate peroxidase proximity labeling coupled with biochemical fractionation identifies promoters of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16382–16392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hung, V.; Lam, S.S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Guzman, G.; Mootha, V.K.; Carr, S.A.; Ting, A.Y. Proteomic mapping of cytosol-facing outer mitochondrial and ER membranes in living human cells by proximity biotinylation. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrera-Cruz, M.S.; Simmen, T. Over Six Decades of Discovery and Characterization of the Architecture at Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 997, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, J.; Janikiewicz, J.; Michalska, B.; Patalas-Krawczyk, P.; Perrone, M.; Ziolkowski, W.; Duszynski, J.; Pinton, P.; Dobrzyn, A.; Wieckowski, M.R. Interaction of Mitochondria with the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Plasma Membrane in Calcium Homeostasis, Lipid Trafficking and Mitochondrial Structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; He, Y.; Lan, B.; Sun, L.; Gao, Y. The MAMs Structure and Its Role in Cell Death. Cells 2021, 10, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10030657

Wang N, Wang C, Zhao H, He Y, Lan B, Sun L, Gao Y. The MAMs Structure and Its Role in Cell Death. Cells. 2021; 10(3):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10030657

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Nan, Chong Wang, Hongyang Zhao, Yichun He, Beiwu Lan, Liankun Sun, and Yufei Gao. 2021. "The MAMs Structure and Its Role in Cell Death" Cells 10, no. 3: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10030657