Abstract

Proper moisture is an essential condition for maintaining the homeostasis of the body, enhancing immunity, and preventing constipation, and it is an indispensable substance for maintaining human life and health. As the bacteria that cause oral disease are affected by water intake, there is a strong relationship between water intake and oral disease. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine the effect of daily water intake on oral disease. The data analyzed were from a seven-year period (2010–2017) from the National Health and Nutrition Survey, conducted annually by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Out of a total of 48,422 people, 134 people in the ‘<1 cup’ group, 27,223 people in the ‘1–4 cups’ group, 14,693 people in the ‘5–7 cups’ group and 6372 people in the ‘>7 cups’ group were selected as subjects. Each time a person drank one less cup of water per day, the prevalence of periodontal disease increased by 1.018 times, the prevalence of dental caries increased by 1.032 times, and the experience of dental caries increased by 1.075 times. Even in Model 2, for which age and gender were adjusted, there was a significant effect. In addition, there was a significant impact in Model 3, which adjusted for oral health behavior, except for permanent caries prevalence. Based on the above results, oral health behavior and state were positive in those who consumed more water per day. Therefore, it is suggested that the government’s active promotion of water intake recommendations and policies should be prepared to include water intake as a component of improving oral health.

1. Introduction

Water accounts for 60% of an adult’s weight. Roughly 70% of the water is distributed within the cells, while the rest is distributed outside the cells in the form of epilepsy, plasma, lymphatic fluid, and other body fluids [1]. This water transports nutrients and waste products as major components of blood and acts as a solvent for various biochemical reactions in the body [2]. In addition, it controls body temperature in the form of sweat, digests food as a component of various digestive fluids, and acts as a lubricant to smoothly move joints and internal organs in the form of synovial fluid and mucus [3,4]. Water also plays a role in protecting the internal organs and fetus in the cerebrospinal fluid and amniotic fluid of pregnant women. Therefore, proper moisture is an essential condition for maintaining the homeostasis of the body, enhancing immunity, and preventing constipation, and it is an indispensable substance in maintaining human life and health [5]. When the balance of water is broken or the body lacks too much water, the human body exhibits a dehydration reaction. If 2% of the total amount of water in the body decreases, we feel thirst, and if it decreases by 2–4%, muscle fatigue is easily induced, and motor and cognitive functions are reduced. If more than 10% is lost, fatal organ damage and clinical shock can result and put a life at risk, whereas a loss of more than 15–20% can worsen dehydration, thereby leading to death [6,7]. Without water, humans can only survive for 2–4 days [5,8,9]; therefore, maintaining adequate moisture is very important. Since 5–10% of water must be exchanged every day, the amount of water required per day depends on body weight, temperature, activity, and body calorie consumption [10,11,12,13]. As such, the total amount of water intake that must be supplied to our body from the outside is 1–3 L, thereby indicating a wide range [14,15]. Although it is recommended to consume 30 mL per kg of body weight [16] or 1 mL of water per kilocalorie [12], the amount of water that adults consume through water or beverages per day is reported as an average of 2 L [17]. Moreover, as age increases, the intake of water decreases, leading to increased vulnerability to many diseases [18]. Lack of water can cause systemic problems, as well as various health-related symptoms in the oral cavity, such as dry mouth, burning in the mouth due to thirst, or low saliva secretion. If these symptoms persist, it can become an environment that causes oral disease [19]. Saliva is not only necessary to maintain the normal function of oral tissues, but also to suppress oral disease occurrence, and if salivary secretion decreases below normal levels, it can cause oral mucosal diseases and oral diseases. When salivation is lowered, salivary buffering capacity and saliva pH are lowered, and this can significantly cause and increase dental caries [20].

Dental diseases are broadly classified into dental caries and periodontal diseases, both of which are caused by microbial infection. Among more than 500 kinds of bacteria present in the oral cavity, the microbe that is most closely related to dental caries is Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans), a decisive causative agent that induces tooth decay by damaging the hard structure of the teeth [20,21,22]. Prevotella intermedia (P. intermedia), one of the major pathogens of periodontal disease, is known to be a powerful causative agent of adult periodontitis, pregnancy gingivitis, and ulcerative gingivitis [23,24], and it has been reported to be found in oral lesions [22,23]. These bacteria are affected by the amount of water intake; the prevalence of P. intermedia, in particular, decreased as the amount of water intake increased [25]. In Hong’s [20] study, it was reported that less P. intermedia causing the periodontal disease was detected in the group drinking 3 to 4 glasses of water per day, and Jung et al. [25] reported that dental caries-causing S. mutans were detected in the group with the least water intake. However, these differences were not significant results and need to be re-confirmed. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the relationship between dental caries and periodontal disease according to the amount of water ingested per day. The majority of studies previously conducted have examined the relationship between water intake and systemic diseases [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and on water intake relationships in the elderly [18,25]. Furthermore, there are few studies on the relationship between oral health behavior and oral health state in all age groups. Therefore, this study aims to compare demographic characteristics, oral health behaviors, and oral health state according to the amount of water intake by using the 7-year data from the National Health and Nutrition Survey, which represents the Korean people, and identify the substantial impact of water intake on periodontal disease and dental caries in order to use the results as fundamental data confirming the importance of water intake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Data for seven years (2010–2017) from the National Health and Nutrition Survey conducted annually by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were analyzed. Before analyzing the panel survey, we accounted for varying sample sizes from 2010 to 2017 and missing values of variables to ensure a balanced dataset. The National Health and Nutrition Survey is a government-designated, statistics-driven study based on Article 17 of the Statistics Act (approval no. 117002). In the 5th round, the 1st year survey is 2010-02CON-21-C, the 2nd year survey is 2013-12EXP-03-5C, and the 3rd year survey is 2012-01EXP-01-2C. In the 6th round, the 1st year survey is 2013-07CON-03-4C, and the second year survey is 2013-12EXP-03-5C. In the 3rd year, the survey was conducted without deliberation by the Research Ethics Review Committee, as it corresponds to the research conducted by the State for public welfare directly pursuant to Subparagraph 1 of Article 2 (2).

2.2. Study Population

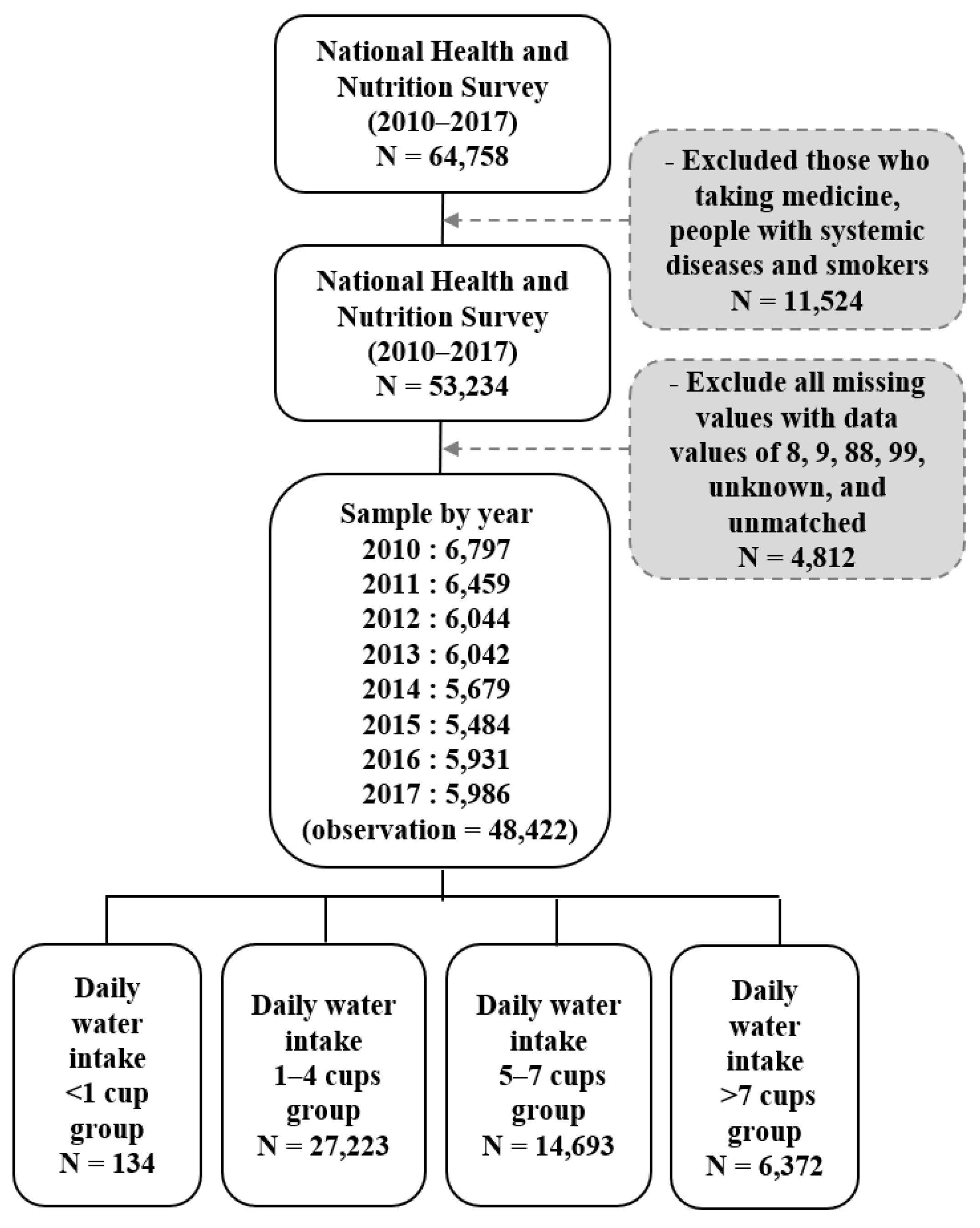

The sampling was performed using a two-stage, stratified, cluster extraction method with probability proportionality. Of the total 64,758, 48,422 people were selected, excluding those who were taking medication, those with systemic diseases, and smokers. Depending on the intake of water, 134 people in the ‘<1 cup’ group, 27,223 people in the ‘1–4 cups’ group, 14,693 people in the ‘5–7 cups’ group and 6372 people in the ‘>7 cups’ group were classified. There were no other ingredients added to the water, and the standard for 1 cup is 200 mL (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow of sample selection in this study.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

We identified demographic characteristics, oral health behaviors, and oral health status as key dependent variables. Demographic characteristics considered were survey year, gender, age, marital status, education, economy, and income, confirmed using the health survey from the National Health and Nutrition Survey. Economy was classified into ‘currently employed’ or ‘unemployed’, and income was classified into ‘low’, ‘middle-low’, ‘middle’, ’middle-high’, and ‘high’. In the oral health behavior section, toothbrushing time consisted of 9 items, and the use of oral health products consisted of 5 items, with 1 for yes and 0 for no. The dental treatment consisted of 9 items, with 1 for the case of receiving treatment and 0 for the case of not receiving treatment. To consider oral health status, chewing inconvenience and experience in toothache were checked, with 1 for yes and 0 for no. Speech problems and chewing problems were measured on a 5-point scale; the higher the score, the less serious the problem. Self-oral health consciousness was also measured on a 5-point scale on which the lower the score, the better. Dental caries and periodontal disease were directly examined by a public health dentist in the province at a mobile examination center. A subject was recorded as having periodontal disease if their periodontal pocket was more than 3 mm deep using a probe. Permanent tooth caries and experience of permanent tooth caries were recorded by checking tooth caries using explorer. The presence of the disease was marked as 1, and the absence of the disease was marked as 0.

2.3.2. Independent Variables

We divided the population into three categories to determine their water intake. In the KNHNS, respondents were asked the question, ‘How much water (mineral water) do you drink per day?’ The unit was measured as ‘cup (200 mL)’, and it was divided into 4 groups as ‘<1 cup’, ‘1–4 cups’, ‘5–7 cups’, ‘>7 cups’ according to water intake.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and complex sampling analysis with stratification variables, colony variables, and weights assigned was applied to all analyses. The comparison of demographic characteristics and oral health behaviors according to 134 people in the ‘<1 cup’ group, 27,223 people in the ‘1–4 cups’ group, 14,693 people in the ‘5–7 cups’ group, and 6372 people in the ‘>7 cups’ group was conducted using a complex sample chi-squared test. Logistic regression analysis and linear regression analysis were performed in order to determine the effect of daily water intake on oral health, and ‘Don’t Know’, ‘Not Applicable’, and ‘Missing Values’ in 8, 9, 88, and 99 were all excluded. Factors affecting the results of regression analysis were identified and analyzed with three models (Model 1: crude model; Model 2: adjusted for age and gender; Model 3: adjusted for oral health behavior). The number of subjects in all tables was presented with an unweighted frequency, and the significance level of the statistical test was set to 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics According to Daily Water Intake

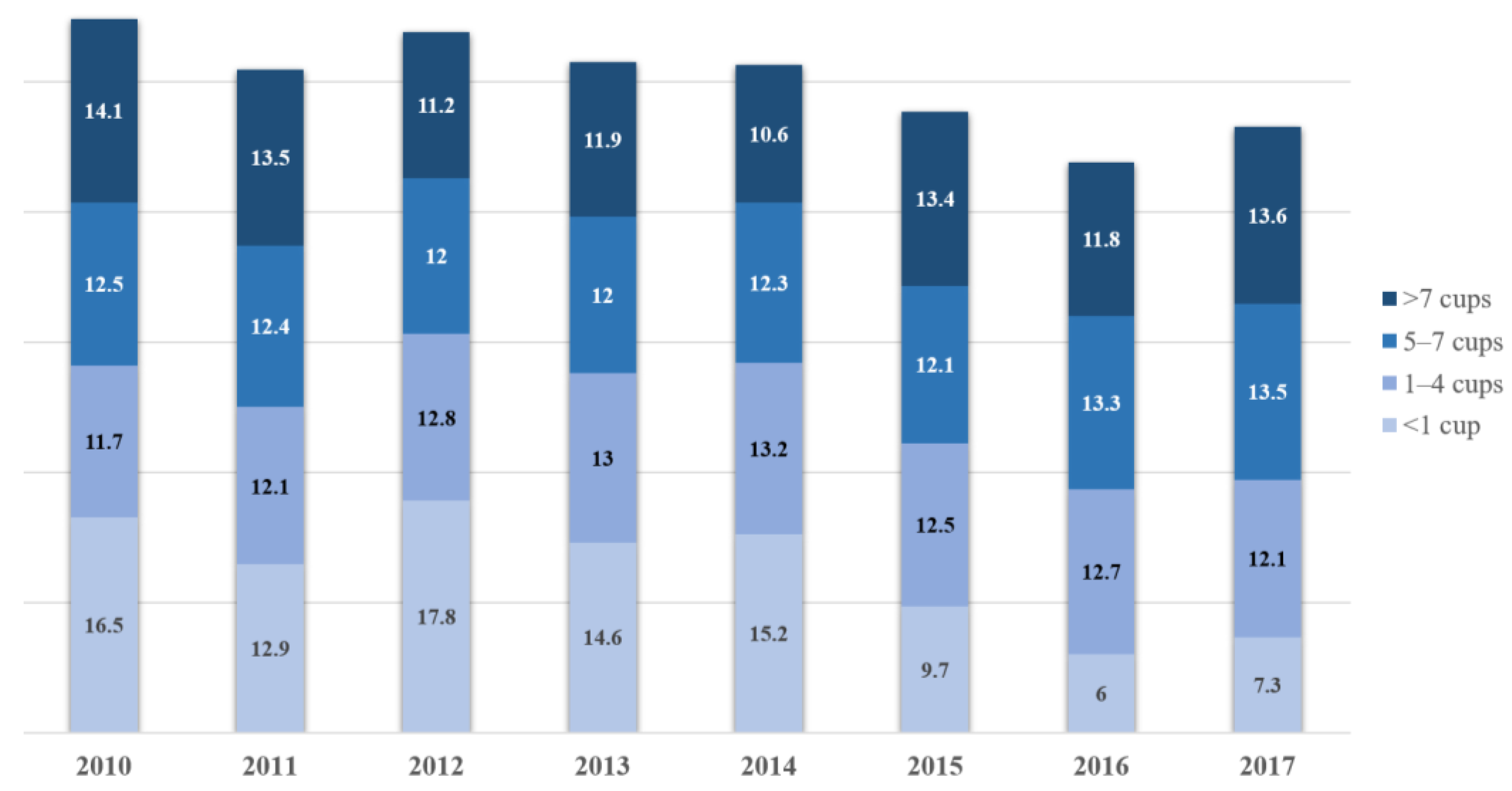

The ratio of the ‘<1 cup’ group was highest in 2012, and the ratio of the ‘1–4 cups’ group was highest in 2014. The ratio of the ‘5–7 cups’ group was highest in 2017, and the ratio of the ‘>7 cups’ group was highest in 2010 (Figure 2). In the ‘<1 cup’ group and ‘>7 cups’ group, the ratio of ‘21–40 years old’ was higher, and in the ‘1–4 cups’ group and ‘5–7 cups’ group, the ratio of ‘41–60 years old’ was higher. In the ‘<1 cup’ group and the ‘1–4 cups’ group, the ratio of women was higher than that of men, and in the ‘5–7 cups’ group and >7 cups’ group, the ratio of men was higher than that of women. As for marital status, the ratio of married people was higher in all groups. In the ‘<1 cup’ group and ‘>7 cups’ group, middle-low income was highest. In the ‘1–4 cups’ group, low income was highest, and in the ‘5–7 cups’ group, middle income was highest. As for education, in the ‘<1 cup’ group, university graduate was highest, and in the ‘1–4 cups’ group, elementary school graduate was highest. In the ‘5–7 cups’ and ‘>7 cups’ groups, high school graduate was highest. In terms of economic activities, employed was higher than currently unemployed regardless of the group. There were significant differences in all items of demographic characteristics (Table 1) (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Percentage of daily water intake by year (%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics according to daily water intake N (%).

3.2. Oral Health Behavior According to Daily Water Intake

In terms of toothbrushing, brushing before dinner and before going to bed was highest in the ‘<1 cup’ group, brushing after breakfast, after lunch, and after dinner was highest in the ‘5–7 cup’ group, and brushed yesterday, brushing before breakfast, before lunch, and after a snack was highest in the ‘>7 cups’ group. There were significant differences in all items. As for the use of oral health products, the use of electric toothbrushes was highest in the ‘<1 cup’ group, the use of oral health products and mouthwash was highest in the ‘5–7 cups’ group, and the use of floss and interdental brush was highest in the ‘>7 cups’ group; there were significant differences in all items except for the use of oral health products. In dental treatment, simple caries treatment and prosthetic treatment were highest in the ‘<1 cup’ group; went to the dentist, oral examination, and periodontal treatment were highest in the ‘5–7 cups’ group; and pulp treatment, oral health care, surgical treatment, and trauma treatment were highest in the ‘>7 cups’ group. There were significant differences in all items except went to the dentist, oral examination, simple caries treatment, trauma treatment, and prosthetic treatment (Table 2) (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Oral health behavior according to daily water intake N (%).

3.3. Oral Health Status According to Daily Water Intake

Chewing inconvenience was highest in the ‘1–4 cups’ group, and the experience in toothache was highest in the ‘<1 cup’ group. It was confirmed that speech and chewing problems were less in the ‘>7 cups’ group, and self-oral health consciousness was worst in the ‘<1 cup’ group. There were significant differences in all items. In addition, the prevalence of periodontal disease increased by 1.018 times, the prevalence of dental caries increased by 1.032 times, and the experience of dental caries increased by 1.075 times each time a person drank one less cup of water per day. Even in Model 2, for which age and gender were adjusted, there was a significant effect. In addition, there was significant impact in Model 3, which adjusted for oral health behavior, except for permanent caries prevalence (Table 3) (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Oral health status according to daily water intake N(%).

4. Discussion

As interest in immunity increases following the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in the effect of water intake on immune function and systemic diseases is growing [26]. Recently, it has been suggested that mild dehydration can lead to changes in various cognitive functions, such as concentration, arousal, and short-term memory [27]. On the other hand, Benton [28] argued that there are very few studies on the effect of dehydration on cognitive function, and confounding factors such as fatigue and body temperature related to dehydration are not well controlled, thereby making it difficult to draw a definite conclusion. While studies on water, systemic diseases, and mental disorders continue, studies confirming the relationship between water and oral disease are mostly those related to bacteria [25] and those limited to the elderly [18,25]. For this reason, it is necessary to expand these studies; as such, this study expanded and investigated subjects by using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Survey representing Korea and analyzed the relationship between water and oral disease through the data from 2010 to 2017.

Women’s water intake was lower than that of men, which is the same result reported in studies conducted in the US and Canada [29,30,31] and is theorized to be a complex result influenced by female hormones [32]. Differences in water intake according to gender are an area requiring further research. In addition, it is necessary to consider socioeconomic aspects to increase water intake, as the water intake was lower in high-income, education, and unemployed states.

In regard to toothbrushing among the oral health behaviors, water intake was high in all groups except for before dinner and before going to bed and was also high in all groups using oral health products except for the use of electric toothbrushes in which water intake was high. This indicates that oral health behavior is good in the group that consumes more water per day, which is consistent with the study of Nam et al. [19] that water intake behavior and oral care behavior are related. However, there is no relationship between tongue brushing, the number of brushings, brushing time, and the use of auxiliary oral hygiene products among oral health behaviors; as a result, further research is deemed necessary. In addition, it was found that the group with high water intake received relatively simple treatments and preventive treatments, and the group with low water intake received more serious treatments. It is theorized that people receive more treatment to maintain and promote oral health due to a higher degree of interest in health, including water intake.

In the oral health status section, the group who consumed less water per day experienced a high incidence of toothache and perceived that they had bad oral health status. In addition, the group with high water intake had no speech problems, chewing problems, or chewing inconvenience. As such, it was confirmed that oral health and water intake are highly related, as oral health problems were low in the group who consumed more water per day. In fact, the prevalence of periodontal disease increased by 1.018 times, the prevalence of dental caries increased by 1.032 times, and the experience of dental caries increased by 1.075 times each time a person drank one less cup of water per day. Although this was analyzed by adjusting for age, gender, and oral health behavior affecting water intake and oral disease, the result was found to be significant, thereby confirming the importance of water intake for oral disease.

Since dental caries and periodontal disease are multifactorial diseases in which several factors act in combination, water intake cannot be limited as the cause of increasing or decreasing the likelihood of oral disease. In addition, periodontal disease was diagnosed when the depth of the periodontal pocket was 3 mm or more in the examination for the prevalence of periodontal disease investigated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. This can lead to overdiagnosis if the depth of the periodontal pocket is 3 mm in the case of prosthetic teeth or implants that are not natural teeth. Nevertheless, it has been confirmed that water intake is highly related to oral diseases, and so it is thought that a recommended intake of water should be included in dietary guidelines to prevent oral diseases considering the importance of water intake. A limitation of this study is that only associations, not causal relationships, can be drawn from the results owing to its cross-sectional design, where investigations are restricted to a certain point within a short window of time. Another limitation is that there are very few previous studies on water intake and oral health behaviors and state for all age groups, so it was somewhat difficult to compare and interpret the results of this study. A final limitation was that we did not consider other sources of hydration (e.g., from other drinks and liquid foods, as well as environmental (micro)/climatic conditions and lifestyles related to hydration, such as humidity and temperature, physical activity, sport, drugs, water fluoridation area, eating habits, etc.) that could influence the results of this study. Therefore, additional research considering the various water sources of the subject is required. Despite these limitations, it is meaningful that this study was analyzed through representative data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to motivate Koreans regarding water intake. Moreover, this study is significant in providing data that can be used for direction setting when establishing policies or business plans for the recommendation of water intake at the national level. The relationship between water intake and oral health requires further and continuous research, and follow-up studies to establish standards of proper water intake in order to lower oral disease are necessary.

5. Conclusions

Based on the above results, people who consumed more water were at lower risk of dental caries and periodontal disease. Additionally, people who consumed more water were at lower risk of poor oral health status. Therefore, it is concluded that the government’s active promotion of water intake recommendations and policies should be prepared to include water intake as important in support of improved oral health.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (In the 5th round, the 1st year survey is 2010-02CON-21-C, the 2nd year survey is 2013-12EXP-03-5C, and the 3rd year survey is 2012-01EXP-01-2C. In the 6th round, the 1st year survey is 2013-07CON-03-4C, and the 2nd year survey is 2013-12EXP-03-5C. In the 3rd year, the survey was conducted without deliberation by the Research Ethics Review Committee, as it corresponds to the research conducted by the State for public welfare directly pursuant to Subparagraph 1 of Article 2 (2).).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This study used the KNHANES data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jéquier, E.; Constant, F. Water as an essential nutrient: The physiological basis of hydration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrier, E.; Vergne, S.; Klein, A.; Poupin, M.; Rondeau, P.; Le Bellego, L.; Armstrong, L.E.; Lang, F.; Stookey, J.; Tack, I. Hydration biomarkers in free-living adults with different levels of habitual fluid consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.S. The effects of gender, obesity rate, nutrition knowledge and dietary attitude on the dietary self-efficacy on adolescents. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2003, 8, 652–657. [Google Scholar]

- Swallow, J.A. Quantitative study of enamel dissolution under conditions of controlled hydrodynamics. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 56, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbalis, J.G. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 17, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1459. [Google Scholar]

- Hillyer, M.; Menon, K.; Singh, R. The effects of dehydration on skill-based performance. Int. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 5, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.C.; Popkin, B.M. Impact of water intake on energy intake and weight status: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, J.L.; Wassner, S.J. Body composition: Salt and water. Pediatr. Rev. 2006, 27, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: Are they appropriate? Pediatrics. 2011, 127, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sawka, M.N.; Latzka, W.A.; Matott, R.P.; Montain, S.J. Hydration effects on temperature regulation. Int. J. Sports Med. 1998, 19, S108–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawka, M.N.; Cheuvront, S.N.; Carter, R. Human water needs. Nutr. Rev. 2005, 63, S30–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, A.; Schoeller, D.A.; Subar, A.F.; Troiano, R.; Schatzkin, A.; Harris, T.; Bauer, D.; Bingham, S.A.; Everhart, J.E.; Newman, A.B.; et al. Water turnover in 458 American adults 40–79 yr of age. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004, 286, F394–F401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate (the US/Canada); Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water; The National Academies Press: Washington DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidester, J.; Spangler, A. Fluid intake in the institutionalized elderly. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 1997, 97, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddes, J.J.; Emmanuel, E.J.; Zuidhoft, M.J. Broiler performance, body weight variance, feed and water intake, and carcass quality at different stocking densities. Poultry Sci. 2002, 81, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pêgo, C.; Guelinckx, I.; A Moreno, L.; Kavouras, S.; Gandy, J.J.; Martinez, H.; Bardosono, S.; Abdollahi, M.; Nasseri, E.; Jarosz, A.; et al. Total fluid intake and its determinants: Cross-sectional surveys among adults in 13 countries worldwide. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong-Esther, C.; Browne, K.; Armstrong-Esther, D.; Sander, L. The institutionalized elderly: Dry to the bone! Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1996, 33, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.M.; Choi, S.H.; Jeon, H.I.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, M.K. The influence of water drinking on oral management behavior and bad breath in college students. AJMAHS 2017, 7, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.H. Study on detection of oral bacteria in the saliva and risk factors of adults. JKAIS 2014, 15, 5675–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, K.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, H.S.; Jin, I. Analysis of gene expression in response to acid stress of streptococcus mutans Isolated from a Korean child. JKAIS 2009, 10, 2990–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, D.F.; Marika, B.; Arthur, C.O. Streptococcus mutans, caries and simulation models. Nutriens 2010, 2, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.N.; Kook, J.K. Development of quantitative real-time PCR primers for detection of development prevotella intermedia. Int. J. Oral Biol. 2015, 40, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, S.Y.; Ku, Y.; Rhyu, I.C.; Hahm, B.D.; Han, S.B.; Choi, S.M.; Chung, C.P. The frequency of detecting prevotella intermedia and prevotella nigrescens in Korean adult periodontitis patients. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2000, 30, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joung, H.Y.; Choi, Y.; Choe, H.J.; Jung, I.H. A Convergence study of Water intake on relationship between Xerostomia, Halitosis, Oral microorganisms in the Elderly. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2019, 10, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, I.Y.; Yun, D.S.; Suh, S.H.; Roh, H.T. Effects of Different Fluid Replacements during Exercise in High Ambient Temperature on Inflammatory Cytokine Responses and Immune Function in Elite Athletes. KJSS 2011, 22, 2076–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; D’Anci, K.E.; Rosenberg, I.H. Water, hydration, and health. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. Dehydration influences mood and cognition: A plausible hypothesis? Nutrients 2011, 3, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kant, A.K.; Graubard, B.I.; Atchison, E.A. Intakes of plain water, moisture in foods and beverages, and total water in the adult US population—Nutritional, meal pattern, and body weight correlates: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, S.; Sherry, B.; O’Toole, T.; Huang, Y. Factors associated with low drinking water intake among adolescents: The Florida Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey, 2007. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2011, 111, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintar, K.D.M.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Charron, D.; Pollari, F.; Fazil, A.; McEwen, S.A.; Nesbitt, A.; Majowicz, S. Water consumption habits of a south-western Ontario community. J. Water Health 2009, 7, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stachenfeld, N.S. Hormonal changes during menopause and the impact on fluid regulation. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).