Pivotal Issues of Water-Based Tourism in Worldwide Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collecting

2.2. Analysis Tools

3. Results

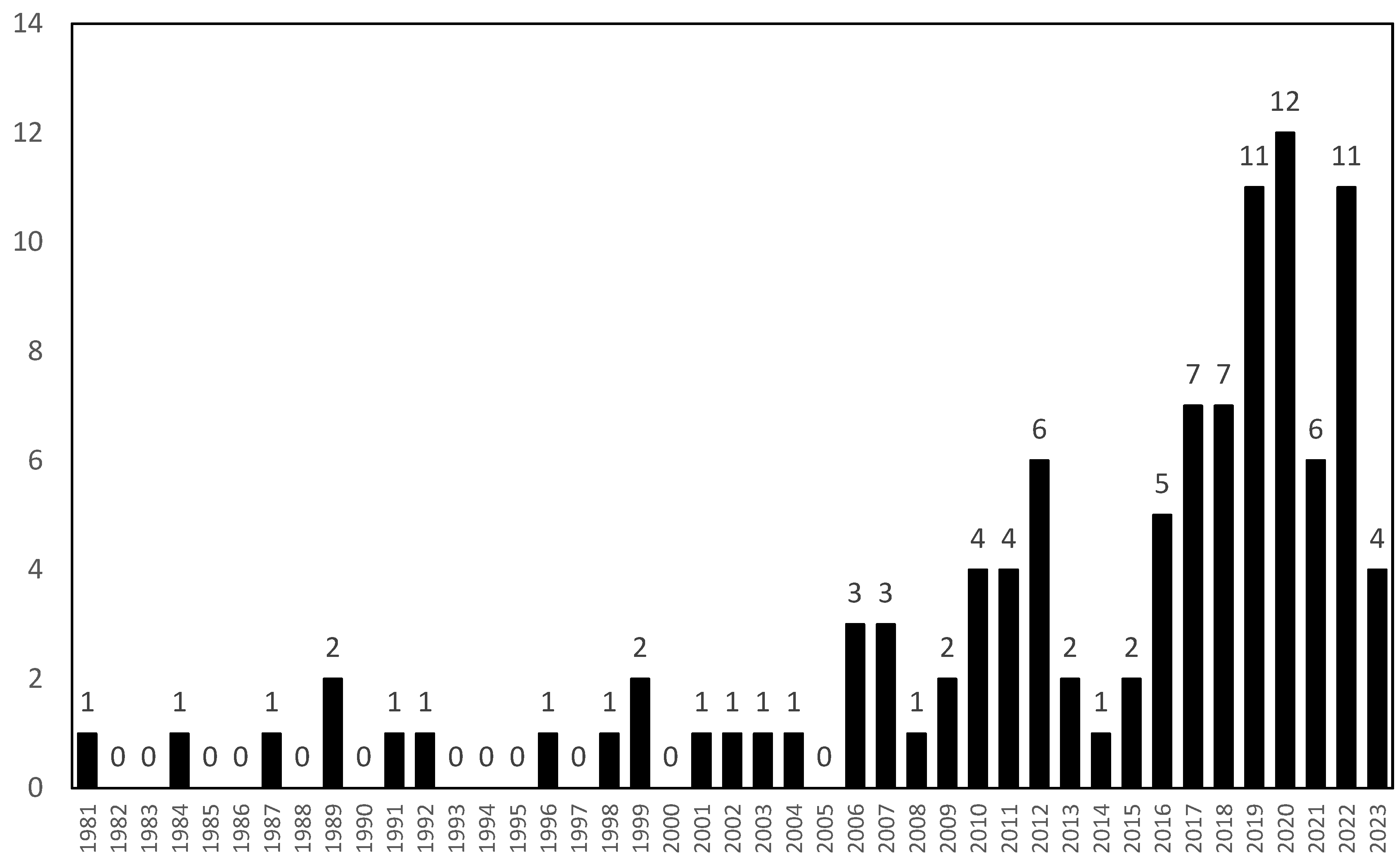

3.1. Annual Number of Water-Based Tourism Document Publication

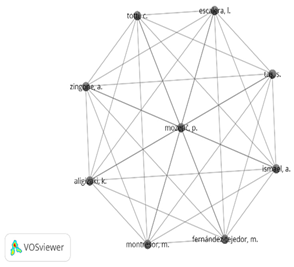

3.2. Author Analysis and Total Document

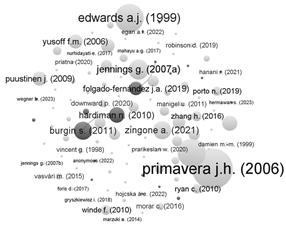

3.3. Citation per Document Analysis

3.4. Subject Area Distribution

3.5. Publisher Distribution

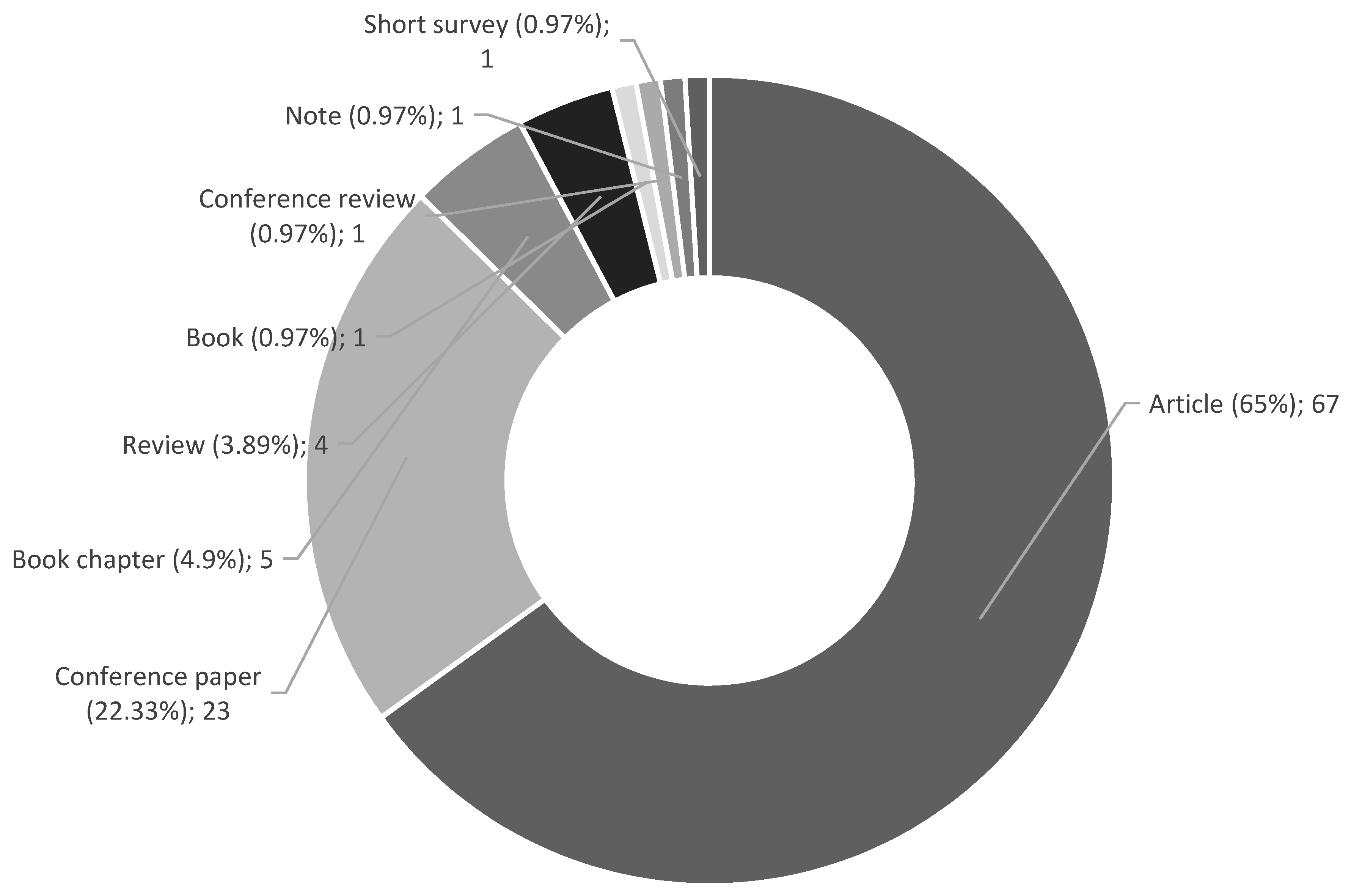

3.6. Document Contribution by Type Distribution

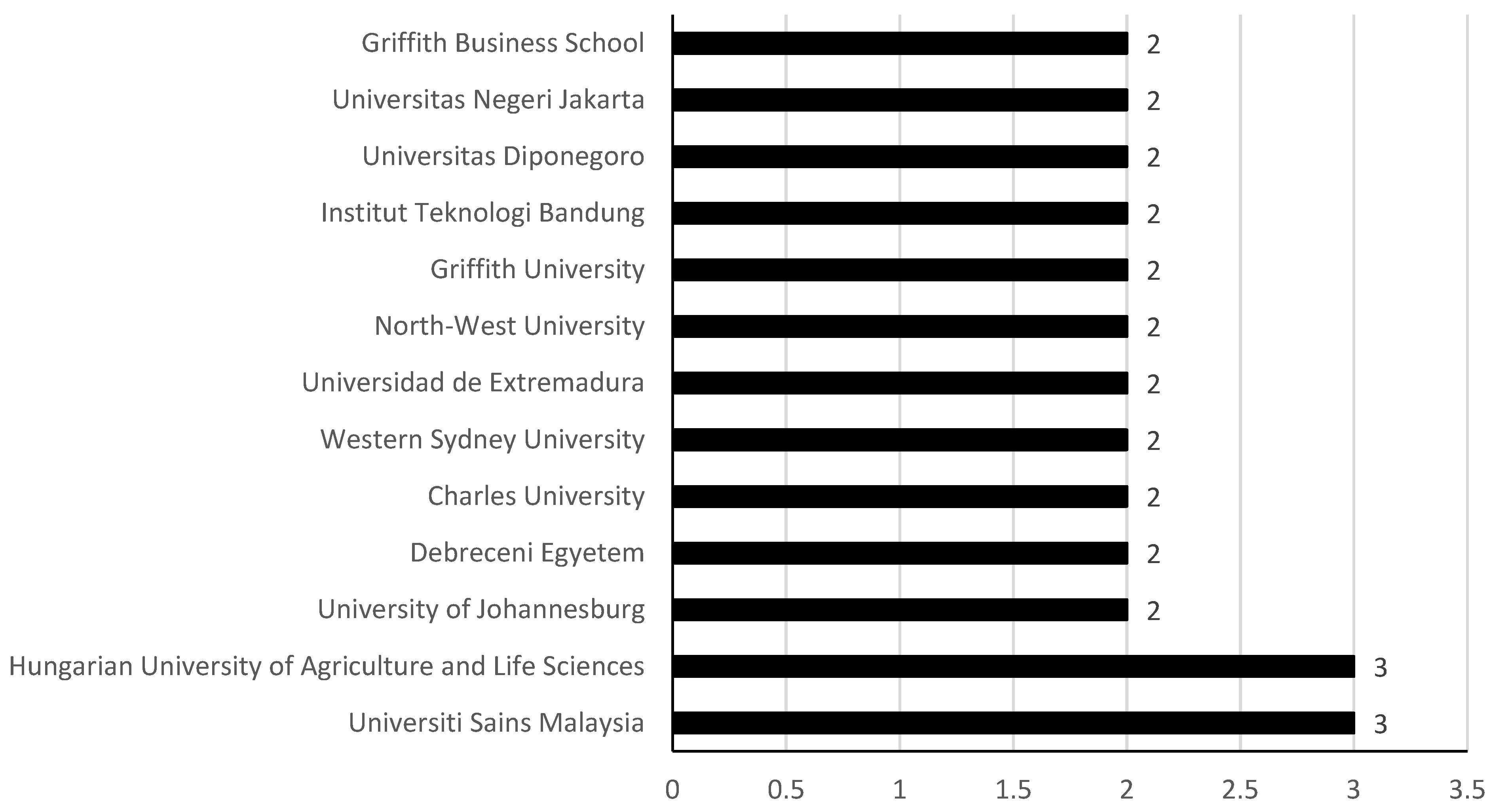

3.7. Document Contribution by Affiliation

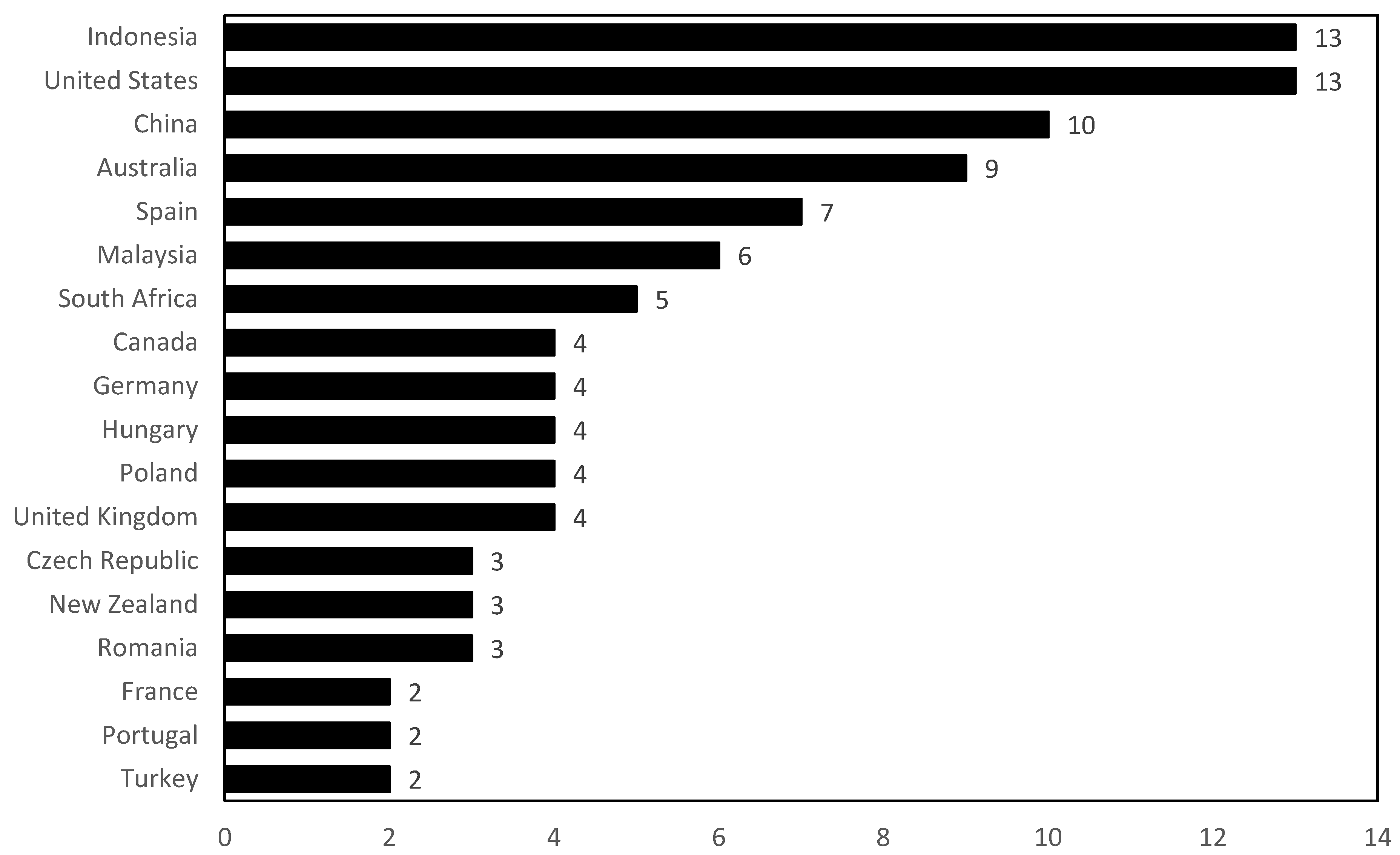

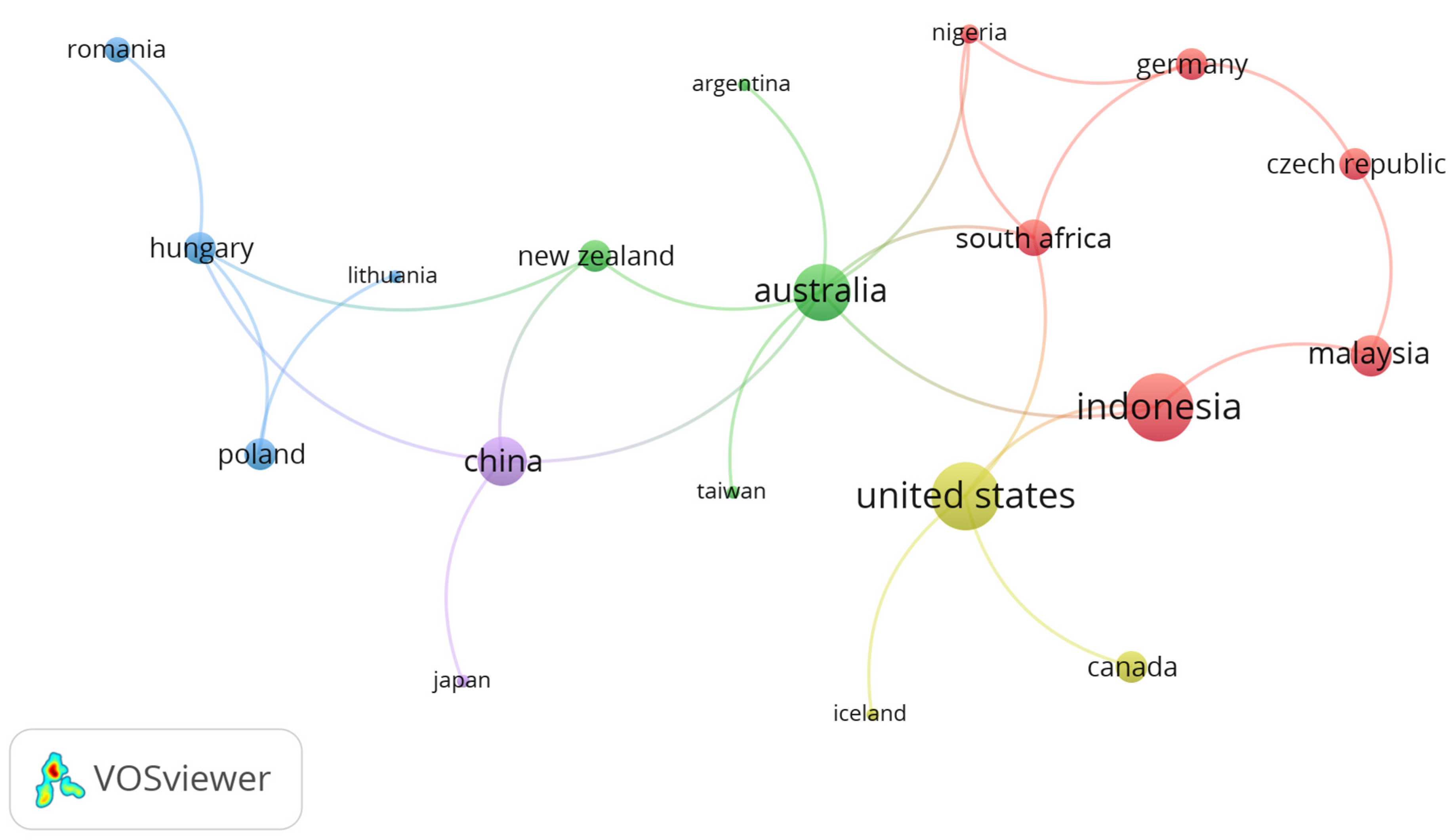

3.8. Countries Distribution

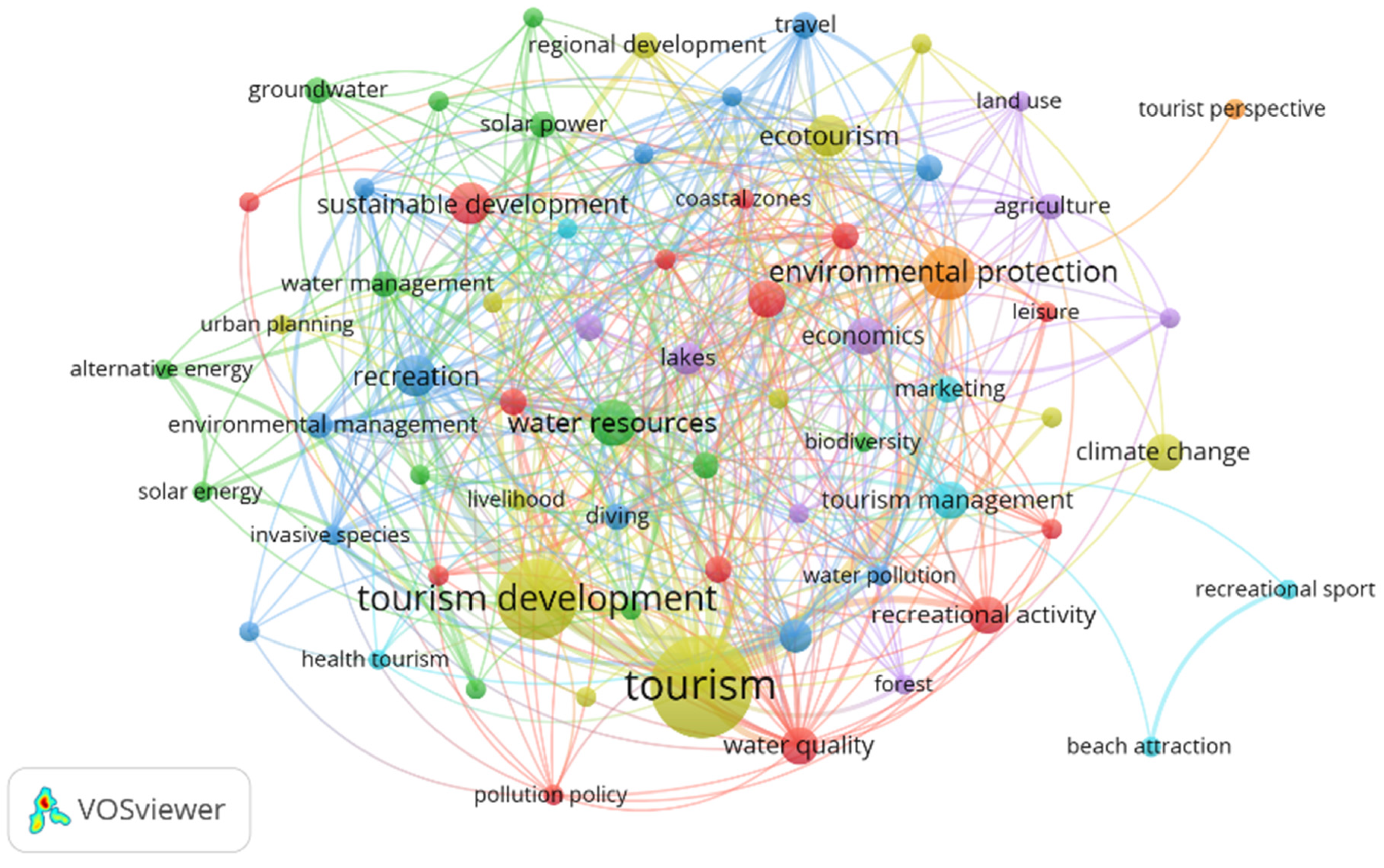

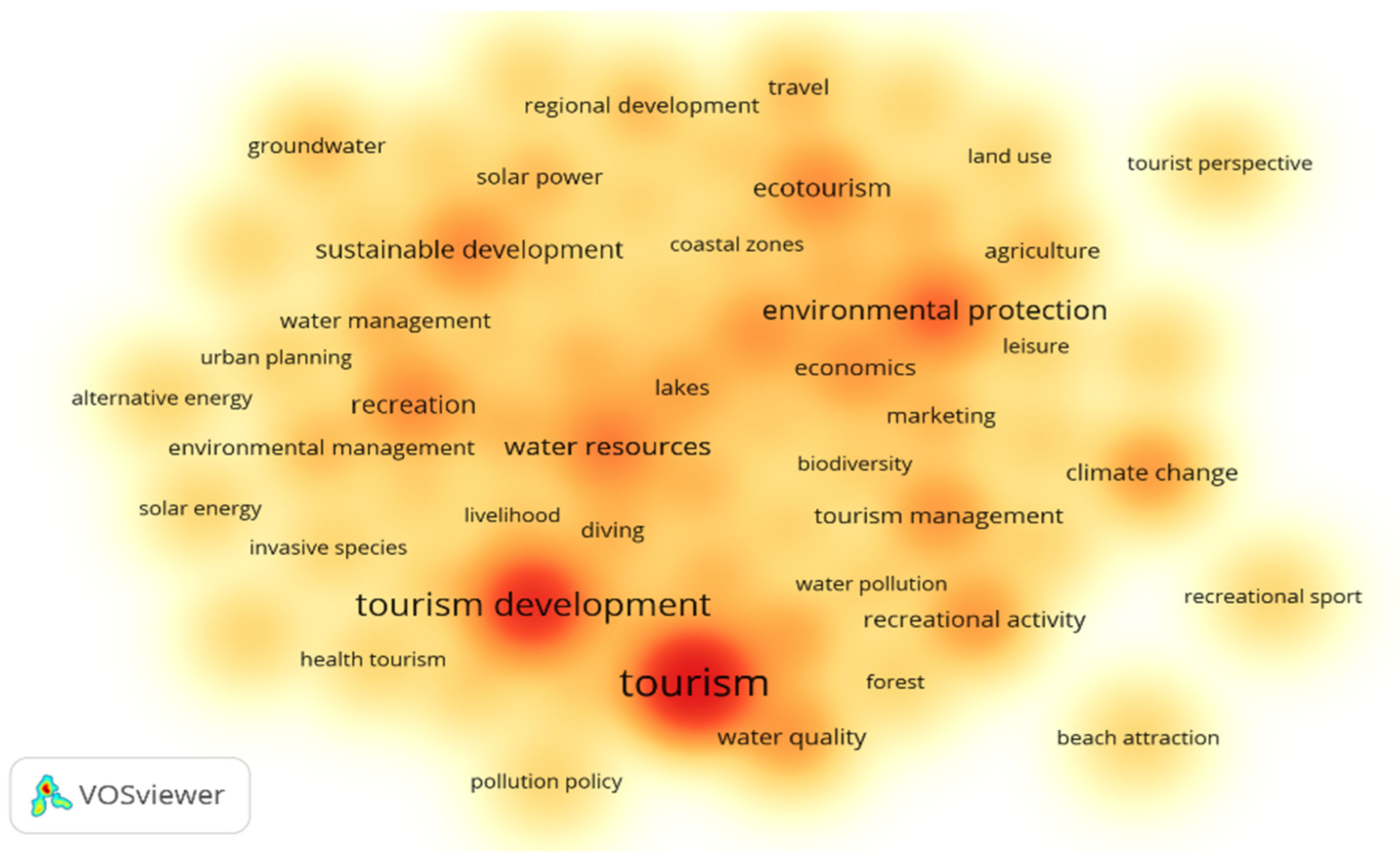

3.9. Network, Overlay, and Density Visualization

3.10. Word Frequencies

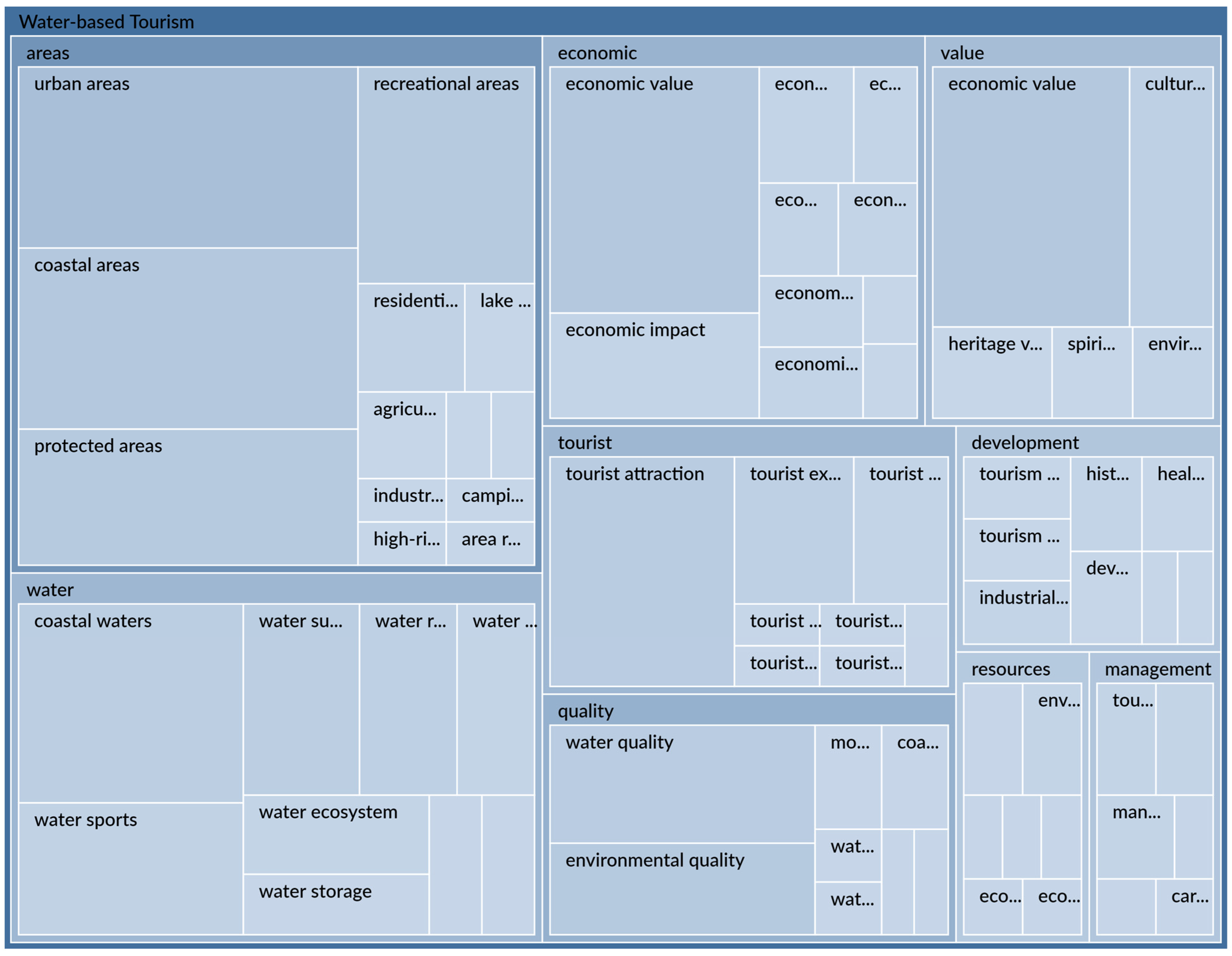

3.11. Pivotal Issue of Water-Based Tourism Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Pivotal Issues of Areas and Water

4.2. Pivotal Issues of Economic, Value, and Tourist

4.3. Pivotal Issues of Quality, Development, Resources, and Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, C.; Peuker-Burkle, E. Water-based tourism on the German Mosel. Ber. Zur Dtsch. Landeskd. 1989, 63, 491–510. [Google Scholar]

- Adekoya, A. Demand for Water-Based Recreational Activities and Tourism Sites in Rural Nigeria. Environ. Educ. Inf. 1991, 10, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G. Water-Based Tourism, Sport, Leisure, and Recreation Experiences. In Water-Based Tourism, Sport, Leisure, and Recreation Experiences; Taylor and Francis: Mount Gravatt, Australia, 2007; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-113634929-4; 075066181X; 978-075066181-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, N. Environmental Protection Culture-Perspective of Tourists in a Water-Based Tourist Destination. In Proceedings of the Current Issues in Hospitality and Tourism Research and Innovations—Proceedings of the International Hospitality and Tourism Conference, IHTC, London, UK, 3–5 September 2012; Universiti Sains Malaysia: George, Malaysia, 2012; pp. 503–507. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaruddin, D.A.; Khan, M.M.A.; Fazil, S.R.; Zulkarnain, Z.; Raman, K. Geological Assessment of Water-Based Tourism Sites in Jeli District, Kelantan, Malaysia. In Springer Water; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wirakusuma, R.M. Water Based Tourism and Recreation Challenges in West Java Province. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Bandung, Indonesia, 8 August 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bandung, Indonesia, 2018; Volume 145. [Google Scholar]

- Mácová, K. Economic Effects of Water-Related Tourism Around the Vltava River Cascade. In Proceedings of the Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Environment Hand in Hand—Proceedings of the 13th Conference, Křtiny, Czech Republic, 9–10 May 2022; Fialová, J., Ed.; Mendel University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2022; pp. 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Vasvári, M.; Boda, J.; Dávid, L.; Bujdosó, Z. Water-Based Tourism as Reflected in Visitors to Hungary’s Lakes. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2015, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprová, K. Water-Related Recreation around the Vltava River and Its Economic Impacts: A Complex Approach. In Proceedings of the Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Sense Hand in Hand, Křtiny, Czech Republic, 13–15 May 2019; Mendel University in Brno: Prague 6, Czech Republic, 2020; pp. 567–571. [Google Scholar]

- Furgała-Selezniow, G.; Jankun-Woźnicka, M.; Woźnicki, P.; Cai, X.; Erdei, T.; Boromisza, Z. Trends in Lakeshore Zone Development: A Comparison of Polish and Hungarian Lakes over 30-Year Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Campón-Cerro, A.M. Water Tourism: A New Strategy for the Sustainable Management of Water-Based Ecosystems and Landscapes in Extremadura (Spain). Land 2019, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downward, P.; Rasciute, S.; Muniz, C. Exploring the Contribution of Activity Sports Tourism to Same-Day Visit Expenditure and Duration. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, C.; Pop, A.-C. Water, Tourism and Sport. A Conceptual Approach. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2016, 18, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.-W.; Huang, H.-C.; Chang, H.-M. An Investigation of Involvement in Serious Leisure, Recreation Specialization, and Sport Tourism of Diving Participants in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the ICIMTR 2012—2012 International Conference on Innovation, Management and Technology Research, Beishiliao, Taiwan, 21–22 May 2012; pp. 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Costa, A. Fluvial Waters and Their Functions for Tourism and Recreation. Recreational and Sport Uses for Rivers and Lakes at Serra Da Estrela (Portugal). In Proceedings of the Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Guarda, Portugal, 2022; Volume 293, pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gaman, G.; Răcăşan, B.S.; Potra, A.C. Tourism and Polycentric Development Based on Health and Recreational Tourism Supply. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2017, 19, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Csobán, K.; Szőllős-Tóth, A.; Sánta, Á.K.; Molnár, C.; Pető, K.; Dávid, L.D. Assessment of the Tourism Sector in a Hungarian Spa Town: A Case-Study of Hajdúszoboszló. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 45, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachinger, M.; Rau, H. Forest-Based Health Tourism as a Tool for Promoting Sustainability: A Stakeholder-Based Analysis of Supply-Side Factors in Tourism Product Development. In CSR, Sustainability, Ethics and Governance; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; University of Applied Forest Sciences: Rottenburg, Germany, 2019; pp. 87–104. ISBN 21967075. [Google Scholar]

- Favot, E.J.; Holeton, C.; DeSellas, A.M.; Paterson, A.M. Cyanobacterial Blooms in Ontario, Canada: Continued Increase in Reports through the 21st Century. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2023, 39, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D.; Weaver, D.B.; Gössling, S.; McLennan, C.; Hadinejad, A. Are Water-Centric Themes in Sustainable Tourism Research Congruent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals? J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1821–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; An, X. Assessment of the Sustainable of Water-Based Tourism on the Basis of Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets. Ekoloji 2019, 28, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kuś, S.; Sierka, E.; Jelonek, I.; Jelonek, Z. Synthetic Analysis of Thematic Studies towards Determining the Recreational Potential of Anthropogenic Reservoirs. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2022, 10, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, W.; Lu, J. Suzhou’s Water Grid as Urban Heritage and Tourism Resource: An Urban Morphology Approach to a Chinese City. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, R.S.; Jenkins, I. Travel Behaviour Substitution for a White-Water Canoe Race Influenced by Climate Induced Stream Flow. Leis. Loisir 2018, 42, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başaran, S.T.; Gökçekuş, H.; Orhon, D.; Sözen, S. Autonomous Desalination for Improving Resilience and Sustainability of Water Management in North Cyprus. Desalin. Water Treat. 2020, 177, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Yan, X.; Alimov, A.; Farmanov, E.; Dávid, L.D. Regional Sustainability: Pressures and Responses of Tourism Economy and Ecological Environment in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabil, M.; Alayan, R.; Lakner, Z.; Dávid, L.D. Enhancing Regional Tourism Development in the Protected Areas Using the Total Economic Value Approach. Forests 2022, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozes, T.A. From the Paradise of Beit Shean Valley to the Contested Landscape of the Valley of Springs: Water Amenities, Environmental Justice, and Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Technion, Israel Institute of Technology: Haifa, Israel, 2022; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mimbs, B.P.; Boley, B.B.; Bowker, J.M.; Woosnam, K.M.; Green, G.T. Importance-Performance Analysis of Residents’ and Tourists’ Preferences for Water-Based Recreation in the Southeastern United States. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Neela, N.M. Adventure Tourists’ Electronic Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM) Intention: The Effect of Water-Based Adventure Experience, Grandiose Narcissism, and Self-Presentation. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 22, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.J. Risk, Competence and Adventure Tourists: Applying the Adventure Experience Paradigm to White-Water Rafters. Leis. Loisir 2001, 26, 2–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, T.V.; Denny, C.B.; Pennisi, L.A. Using Visitors’ Motivations to Provide Learning Opportunities at Water-Based Recreation Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahayu, A.G. Perception Study about Visitors Related to Development of Rowo Bayu Attractions in Kecamatan Songgon Banyuwangi. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Malang, Indonesia, 6–7 March 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Malang, Indonesia, 2017; Volume 70. [Google Scholar]

- Mondok, A.; Kóródi, M.; Kárpáti, J.; Pallás, I.E.; Gogo, F.C.A.; Dávid, L.D. The Contradictious Expectations of the Actors of the Tourism Organizational and Consumer Market in Sustainable Destination Development. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busarova, V. Recreation Potential and Water-Based Recreation Resources in Karelia (Example of the Zaonezhje Area). In Proceedings of the Vide, Tehnologija, Resursi—Environment, Technology, Resources; Rezekne Higher Education Institution: Rēzekne, Latvia, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, A.L.; Rolfe, J.; Cassells, S.; Chilvers, B.L. Potential Changes in the Recreational Use Value for Coastal Bay of Plenty, New Zealand Due to Oil Spills: A Combined Approach of the Travel Cost and Contingent Behaviour Methods. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 228, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunacini, J.; Goralnik, L.; Rutty, M.; Keller, E. Industrial Transitions in Michigan: Stakeholder Perspectives on Water Resources Restoration and Community Vibrancy. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2023, 36, 928–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávid, L. A Vásárhelyi Terv Turisztikai Lehet\Hoségei. Gazdálkodás Sci. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 48, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Duda-Gromada, K.; Bujdosó, Z.; David, L. Lakes, Reservoirs and Regional Development through Some Examples in Poland and Hungary. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2010, 5, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- David, L.; Baros, Z.; Patkos, C.; Tuohino, A. Lake Tourism and Global Climate Change: An Integrative Approach Based on Finnish and Hungarian Case-Studies. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2012, 7, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, G.; Dávid, L.; Bujdosó, Z. A hazai folyók által érintett települések társadalmi-gazdasági vizsgálata [Socio-economic analysis of the municipalities affected by domestic rivers]. Foldrajzi Kozlemenyek 2010, 134, 189–202. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Kapsch, A.E. Tourism in the Mecklenburg Lake District. Geogr. Rundsch. 2019, 71, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M.; van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Large-Scale Comparison of Bibliographic Data Sources: Scopus, Web of Science, Dimensions, Crossref, and Microsoft Academic. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2021, 2, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Côté, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a Curated, High-Quality Bibliometric Data Source for Academic Research in Quantitative Science Studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpulainen, M.; Seppänen, M. Combining Web of Science and Scopus Datasets in Citation-Based Literature Study. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 5613–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Archi, Y.; Benbba, B.; Zhu, K.; El Andaloussi, Z.; Pataki, L.; Dávid, L.D. Mapping the Nexus between Sustainability and Digitalization in Tourist Destinations: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Archi, Y.; Benbba, B.; Nizamatdinova, Z.; Issakov, Y.; Vargáné, G.I.; Dávid, L.D. Systematic Literature Review Analysing Smart Tourism Destinations in Context of Sustainable Development: Current Applications and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archi, Y.E.; Benbba, B. The Applications of Technology Acceptance Models in Tourism and Hospitality Research: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2023, 14, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J. Software Tools for Conducting Bibliometric Analysis in Science: An up- to-Date Review. Prof. Inf. Ción 2020, 29, e290103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajovic, I.; Boh Podgornik, B. Bibliometric Analysis of Visualizations in Computer Graphics: A Study. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markscheffel, B.; Schröter, F. Comparison of Two Science Mapping Tools Based on Software Technical Evaluation and Bibliometric Case Studies. Collnet J. Scientometr. Inf. Manag. 2021, 15, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. Exploratory Bibliometrics: Using VOSviewer as a Preliminary Research Tool. Publications 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkin, S.; Forster, N.; Hodgson, P.; Lhussier, M.; Carr, S.M. Using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS; NVivo) to Assist in the Complex Process of Realist Theory Generation, Refinement and Testing. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, D. Analyzing Qualitative Data Using NVivo. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 435–450. ISBN 978-3-030-16064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.; Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; ISBN 978-1-15264-49993-1. [Google Scholar]

- O’neill, M.; Booth, S.; Lamb, J. Using NvivoTM for Literature Reviews: The Eight Step Pedagogy (N7+1). Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Primavera, J.H. Overcoming the Impacts of Aquaculture on the Coastal Zone. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2006, 49, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.J.; Clark, S. Coral Transplantation: A Useful Management Tool or Misguided Meddling? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1999, 37, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, S.; Hardiman, N. The Direct Physical, Chemical and Biotic Impacts on Australian Coastal Waters Due to Recreational Boating. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Maya, C.; Uche-Marcuello, J.; Martínez-Gracia, A.; Bayod-Rújula, A.A. Design Optimization of a Polygeneration Plant Fuelled by Natural Gas and Renewable Energy Sources. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, A.; Escalera, L.; Aligizaki, K.; Fernández-Tejedor, M.; Ismael, A.; Montresor, M.; Mozetič, P.; Taş, S.; Totti, C. Toxic Marine Microalgae and Noxious Blooms in the Mediterranean Sea: A Contribution to the Global HAB Status Report. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, N.; Burgin, S. Recreational Impacts on the Fauna of Australian Coastal Marine Ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 2096–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heggie, T.W.; Heggie, T.M.; Kliewer, C. Recreational Travel Fatalities in US National Parks. J. Travel Med. 2008, 15, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puustinen, J.; Pouta, E.; Neuvonena, M.; Sievänen, T. Visits to National Parks and the Provision of Natural and Man-Made Recreation and Tourism Resources. J. Ecotourism 2009, 8, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, F.M.; Shariff, M.; Gopinath, N. Diversity of Malaysian Aquatic Ecosystems and Resources. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2006, 9, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikunov, V.S.; Belozerov, V.S.; Antipov, S.O. Evaluation of Tourist Activities and Destination Attraction Capacity Using Geotags. Kartogr. Geoinform. 2019, 18, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciu, M.; Berar, F.A.; Dobrea, R.C.; Dima, C. New Approaches of Managers in the Context of the Vuca World; Mendel University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2020; ISBN 9788075097156. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, K.A.; Paredes Cuervo, D. Water Safety and Water Governance: A Scientometric Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, A.H.; Digun-Aweto, O.; Van Der Merwe, P. Potentials of Coasta Land Marine to Urism in Nigeria. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2018, 13, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, S.; Mihardja, E.; Pambudi, D.A.; Jason, J. Hydrodynamic Model Optimization for Marine Tourism Development Suitability in Vicinity of Poso Regency Coastal Area, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winde, F.; Stoch, E.J. Threats and Opportunities for Post-Closure Development in Dolomitic Gold-Mining Areas of the West Rand and Far West Rand (South Africa—A Hydraulic View Part 2: Opportunities. Water SA 2010, 36, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ľoch, B.; Puškárová, P.; Róth, B.; Marcin, M.; Šándorová, K. Impact of Water Quality on Water Based Activities in Hornád River Basin. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM, Sofia, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017; International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference: Košice, Slovakia, 2017; Volume 17, pp. 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, Q.; El Archi, Y.; Kabil, M.; Remenyik, B.; Dávid, L.D. Tourism Ecological Efficiency and Sustainable Development in the Hanjiang River Basin: A Super-Efficiency Slacks-Based Measure Model Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, N.; Espinola, N. Labor Income Inequalities and Tourism Development in Argentina: A Regional Approach. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 1265–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Huimin, G.; Chon, K. Tourism to Polluted Lakes: Issues for Tourists and the Industry. an Empirical Analysis of Four Chinese Lakes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed Arif, M.; Waqas, A.; Ahmed Butt, F.; Mahmood, M.; Hussain Khoja, A.; Ali, M.; Ullah, K.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Kalam, M.A. Techno-Economic Assessment of Solar Water Heating Systems for Sustainable Tourism in Northern Pakistan. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 5485–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, B.; Meyer, N.; Wolter, C. Paddling Impacts on Aquatic Macrophytes in Inland Waterways. J. Nat. Conserv. 2023, 72, 126331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.M.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M.; Mohammadimanesh, F. Water Quality Monitoring over Finger Lakes Region Using Sentinel-2 Imagery on Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform. In Proceedings of the ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences; Copernicus GmbH: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 5, pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Thi Hong Hanh, V. Canal-Side Highway in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Vietnam—Issues of Urban Cultural Conservation and Tourism Development. GeoJournal 2006, 66, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A. Water, Health, Recreation and Tourism. Water Sci. Technol. 1989, 21, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. Healthy Water-Based Tourism Experiences: Their Contribution to Quality of Life, Satisfaction and Loyalty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; Wilhem Stanis, S.A.; Schneider, I.E.; Heisey, J.J. Crowding and Experience-Use History: A Study of the Moderating Effect of Place Attachment among Water-Based Recreationists. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, O.; Cater, C. Life below Water; Challenges for Tourism Partnerships in Achieving Ocean Literacy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 2428–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhidayati, E.; Buchori, I.; Fariz, T.R. Cellular Automata Modelling in Predicting the Development of Settlement Areas, A Case Study in the Eastern District of Pontianak Waterfront City. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Surabaya, Indonesia, 18 October 2016; Institute of Physics Publishing: Semarang, Indonesia, 2017; Volume 79. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, M.P. Domestic Tourism in Indonesia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1996, 21, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Document | Network |

|---|---|---|

| Bujdosó, Z. | 2 |  |

| Burgin, S. | 2 | |

| Campón-Cerro, A.M. | 2 | |

| Di-Clemente, E. | 2 | |

| Dimmock, K. | 2 | |

| Folgado-Fernández, J.A. | 2 | |

| Handaru, A.W. | 2 | |

| Hardiman, N. | 2 | |

| Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. | 2 | |

| Jennings, G. | 2 | |

| Mardiyati, U. | 2 | |

| Mukhtar, S. | 2 | |

| Nindito, M. | 2 | |

| Yusof, N. | 2 |

| Author | Type | Citation | Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primavera [60] | Article | 349 |  |

| Edwards and Clark [61] | Article | 158 | |

| Rubio-Maya et al. [63] | Article | 154 | |

| Jennings [3] | Book Chapter | 75 | |

| Burgin and Hardiman [62] | Review | 59 | |

| Zingone et al. [64] | Article | 57 | |

| Hardiman and Burgin [65] | Review | 43 | |

| Heggie et al. [66] | Article | 40 | |

| Puustinen et al. [67] | Article | 35 | |

| Yusoff et al. [68] | Review | 33 |

| Subject Area | Document | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Science | 49 | 24.9% |

| Social Sciences | 34 | 17.3% |

| Business, Management and Accounting | 32 | 16.2% |

| Earth and Planetary Sciences | 23 | 11.7% |

| Agricultural and Biological Sciences | 13 | 6.6% |

| Engineering | 12 | 6.1% |

| Energy | 8 | 4.1% |

| Computer Science | 5 | 2.5% |

| Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 5 | 2.5% |

| Medicine | 5 | 2.5% |

| Other | 11 | 5.6% |

| Publisher | Document | % |

|---|---|---|

| IOP Conference Series Earth And Environmental Science | 4 | 3.77% |

| Geojournal Of Tourism And Geosites | 3 | 2.83% |

| Advances In Science Technology And Innovation | 2 | 1.88% |

| Annals Of Tourism Research | 2 | 1.88% |

| International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health | 2 | 1.88% |

| Journal Of Environmental Management | 2 | 1.88% |

| Journal Of Sustainable Tourism | 2 | 1.88% |

| Leisure Loisir | 2 | 1.88% |

| Ocean And Coastal Management | 2 | 1.88% |

| Sustainability Switzerland | 2 | 1.88% |

| Tourism In Marine Environments | 2 | 1.88% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahmat, A.F.; El Archi, Y.; Putra, M.A.; Benbba, B.; Mominov, S.; Liudmila, P.; Issakov, Y.; Kabil, M.; Dávid, L.D. Pivotal Issues of Water-Based Tourism in Worldwide Literature. Water 2023, 15, 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15162886

Rahmat AF, El Archi Y, Putra MA, Benbba B, Mominov S, Liudmila P, Issakov Y, Kabil M, Dávid LD. Pivotal Issues of Water-Based Tourism in Worldwide Literature. Water. 2023; 15(16):2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15162886

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahmat, Al Fauzi, Youssef El Archi, Muhammad Ade Putra, Brahim Benbba, Serik Mominov, Pavlichenko Liudmila, Yerlan Issakov, Moaaz Kabil, and Lóránt Dénes Dávid. 2023. "Pivotal Issues of Water-Based Tourism in Worldwide Literature" Water 15, no. 16: 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15162886

APA StyleRahmat, A. F., El Archi, Y., Putra, M. A., Benbba, B., Mominov, S., Liudmila, P., Issakov, Y., Kabil, M., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Pivotal Issues of Water-Based Tourism in Worldwide Literature. Water, 15(16), 2886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15162886