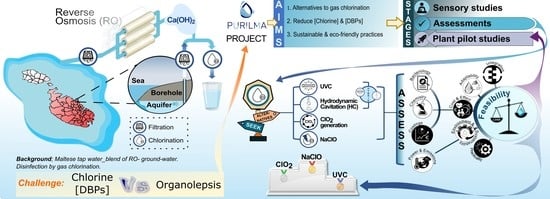

Evaluation of Alternative-to-Gas Chlorination Disinfection Technologies in the Treatment of Maltese Potable Water

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Ultraviolet-light C (UVC) irradiation; the antimicrobial properties of UVC (254 nm) have been demonstrated for a wide range of pathogens [6]. UVC can be easily implemented both at the level of water transfer from the galleries/boreholes to the reservoir, as well as before release to the distribution and reticulation networks, and despite its lack of residual disinfection, it can be combined with chemical processes to achieve greater microbial Log10 reductions in a cost-effective and eco-friendly manner [7]. Additionally, UVC-based treatments contribute negligibly to DBP formation and were shown to attenuate the toxicity of chlorine-derived DBPs [8], thus leaving the water’s organoleptic characteristics unaffected.

- Hydrodynamic cavitation (HC); HC has been emerging as an effective technology of water treatment [9]. HC not only can achieve bacterial reductions in the range of 0.6–5 Log10 without generating DBPs but is also a cost-effective and sustainable method for water softening [10]. It can work synergistically with UVC in the attenuation of dissolved oxygen carbon under advanced oxidation processes [11] and can be combined with electrochlorination for the attenuation of chloroform [12].

- Chlorine dioxide generation; ClO2 (generated in situ) provides an attractive alternative to chlorination as it: (a) is effective at low concentrations (<1 mg/L); (b) is active over a broad pH range (4–10); (c) has a long residual activity; and d) generates fewer harmful DBPs, thus impacting less on the water’s organolepsis [13]. It can be combined with other disinfection technologies, like UVC, to achieve higher microbial reductions [14], and to attenuate DBP formation [15].

- Electrochlorination (NaClO); electrochemically generated sodium hypochlorite will dissociate to hypochlorous acid with subsequent degradation to chlorate and chloride. Though not fundamentally different to gas chlorination, electrochlorination is an attractive technology because: (a) desired end concentrations of active oxidants are generated on site without the need of chlorine gas, thereby reducing transportation and storage necessities and minimising leakage risks [16], (b) it generates less haloacetonitriles than chlorine gas [16], (c) it can remain longer in the distribution system for effective biofilm formation control [16] and (d) it can be combined with physical and chemical disinfection to attenuate DBP formation (Table S7) [15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equipment and Bench-Scale Study Configurations

2.1.1. UVC Set-Up

2.1.2. HC and UVC/HC Set-Up

2.1.3. ClO2 Generation

2.1.4. Eletrochlorination

2.2. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

2.3. Bacterial Inactivation Treatments

2.3.1. UVC

2.3.2. HC and UVC/HC

2.3.3. ClO2 and NaClO

2.4. Colony Counting and Bacterial Inactivation

2.5. Bactericidal Decomposition and Breakpoint Chlorination

2.6. Bacterial Inactivation Kinetics

2.7. Determination of Indicator Parameters and Chemical Analyses

2.8. Statistical Analyses

2.9. Feasibility Assessments

2.9.1. Financial Analyses Assumptions

3. Results

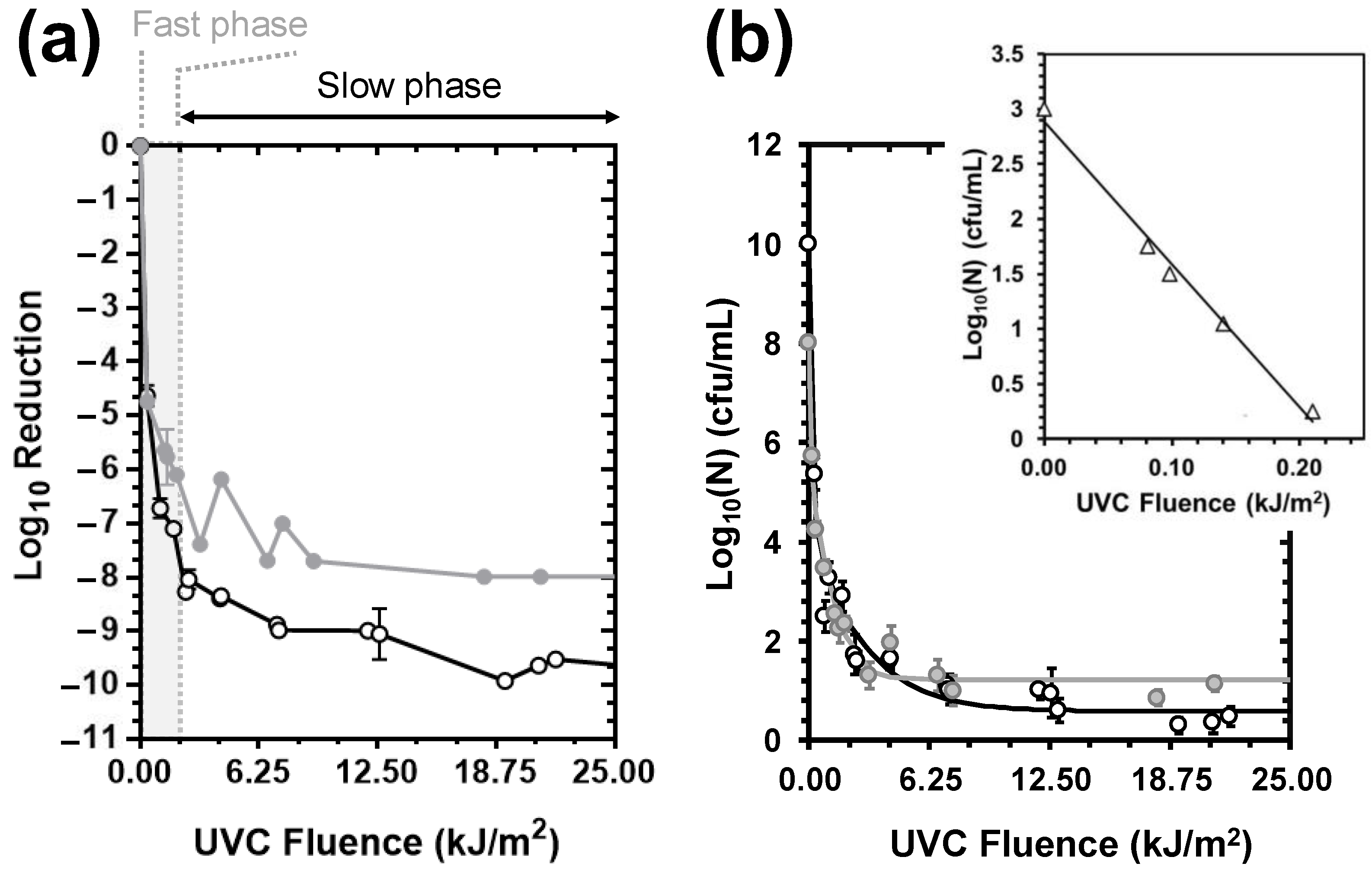

3.1. UVC-Mediated Bacterial Inactivation

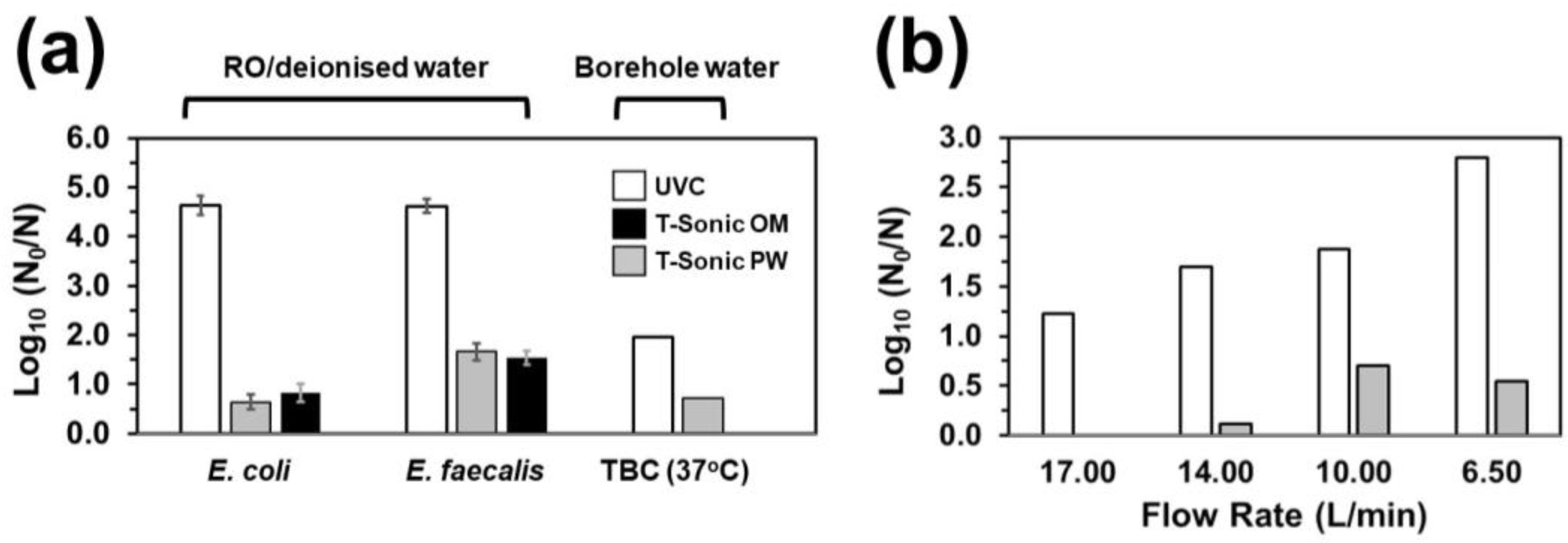

3.2. HC-Mediated Bacterial Inactivation in Borehole Water

3.3. UVC/HC Hybrid Treatment-Mediated Inactivation

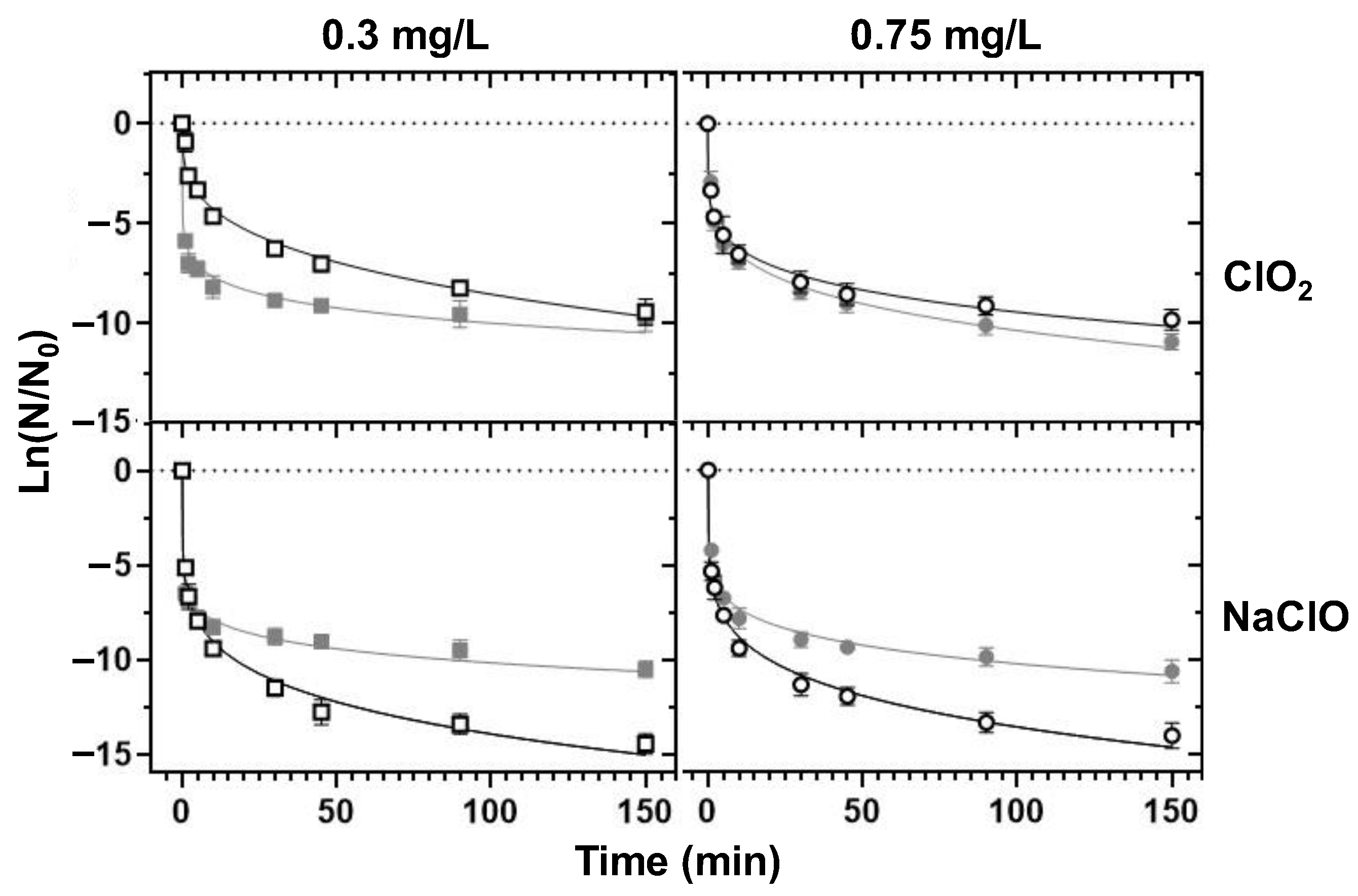

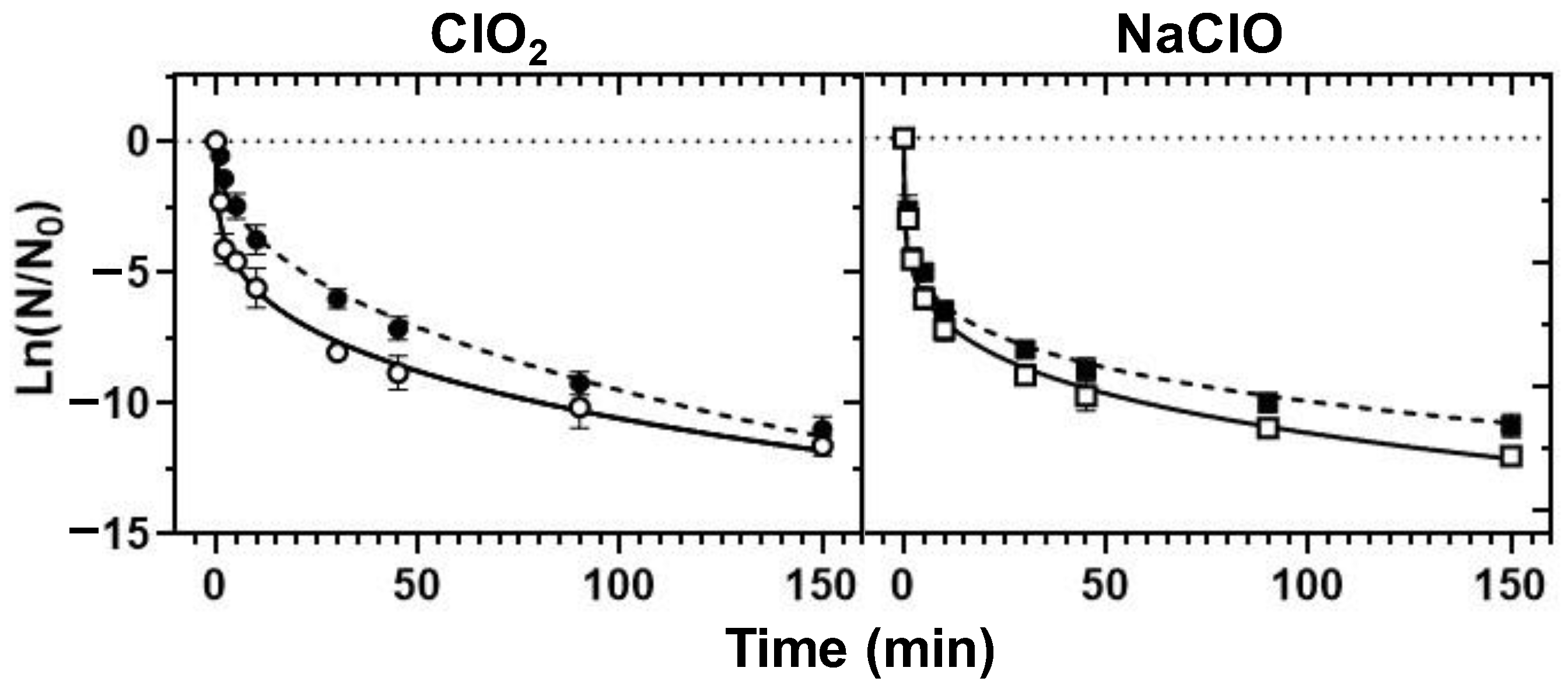

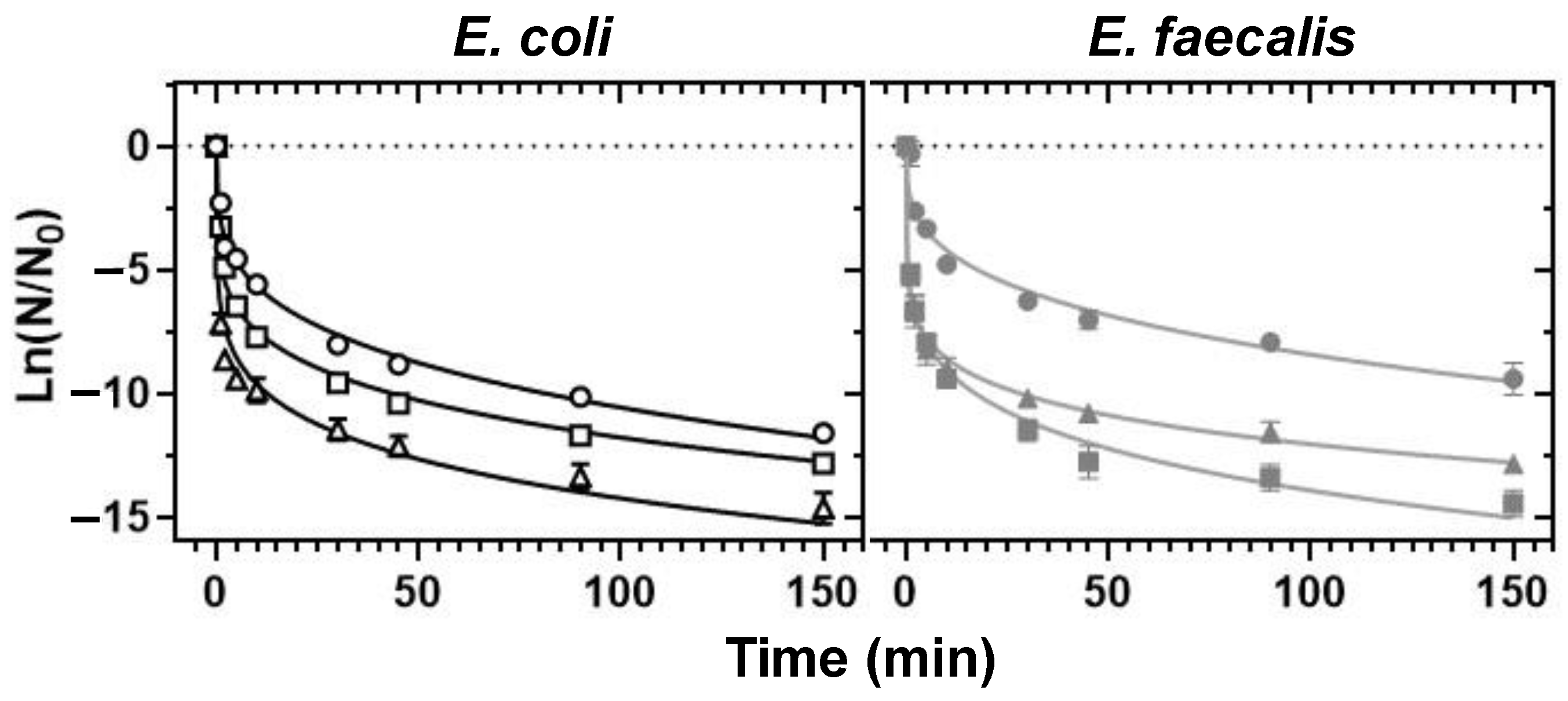

3.4. Chemical Disinfection

3.4.1. Decomposition Half-Lives and Chemical Demand

3.4.2. Decontamination Efficiency

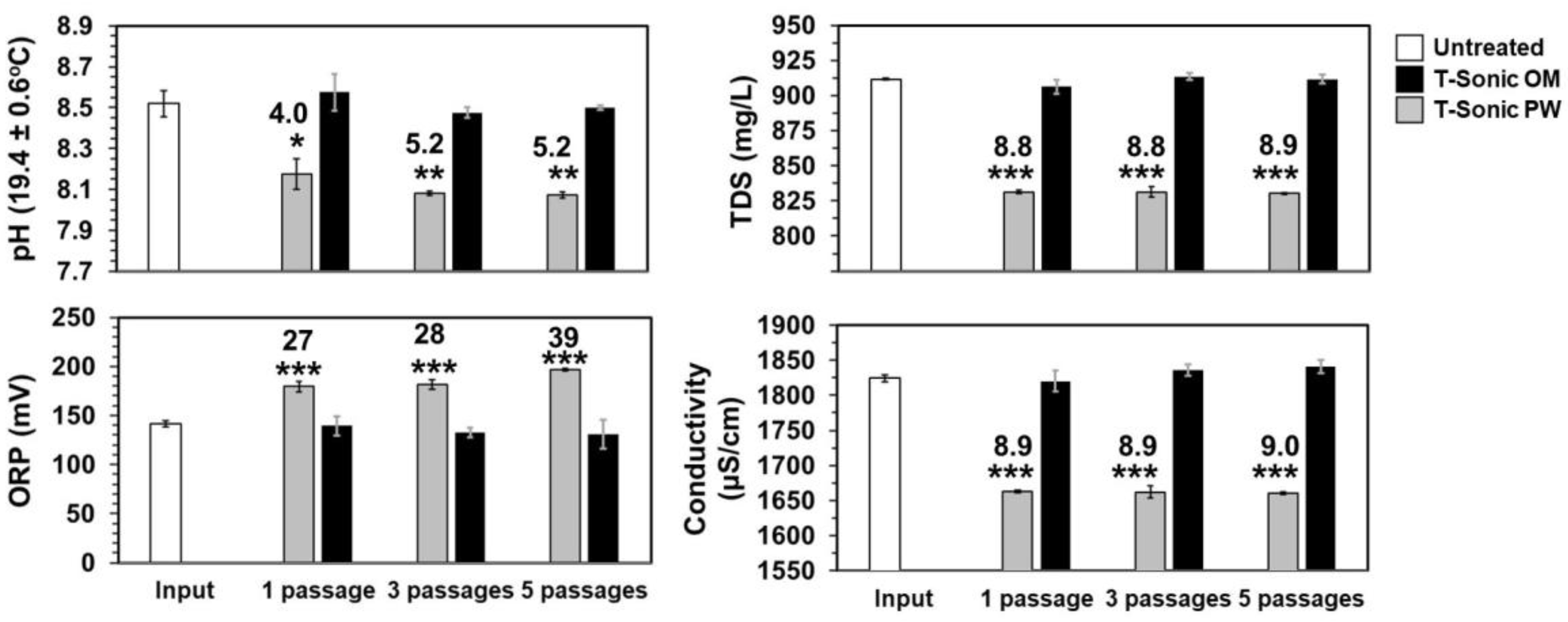

3.5. Chemical Analyses

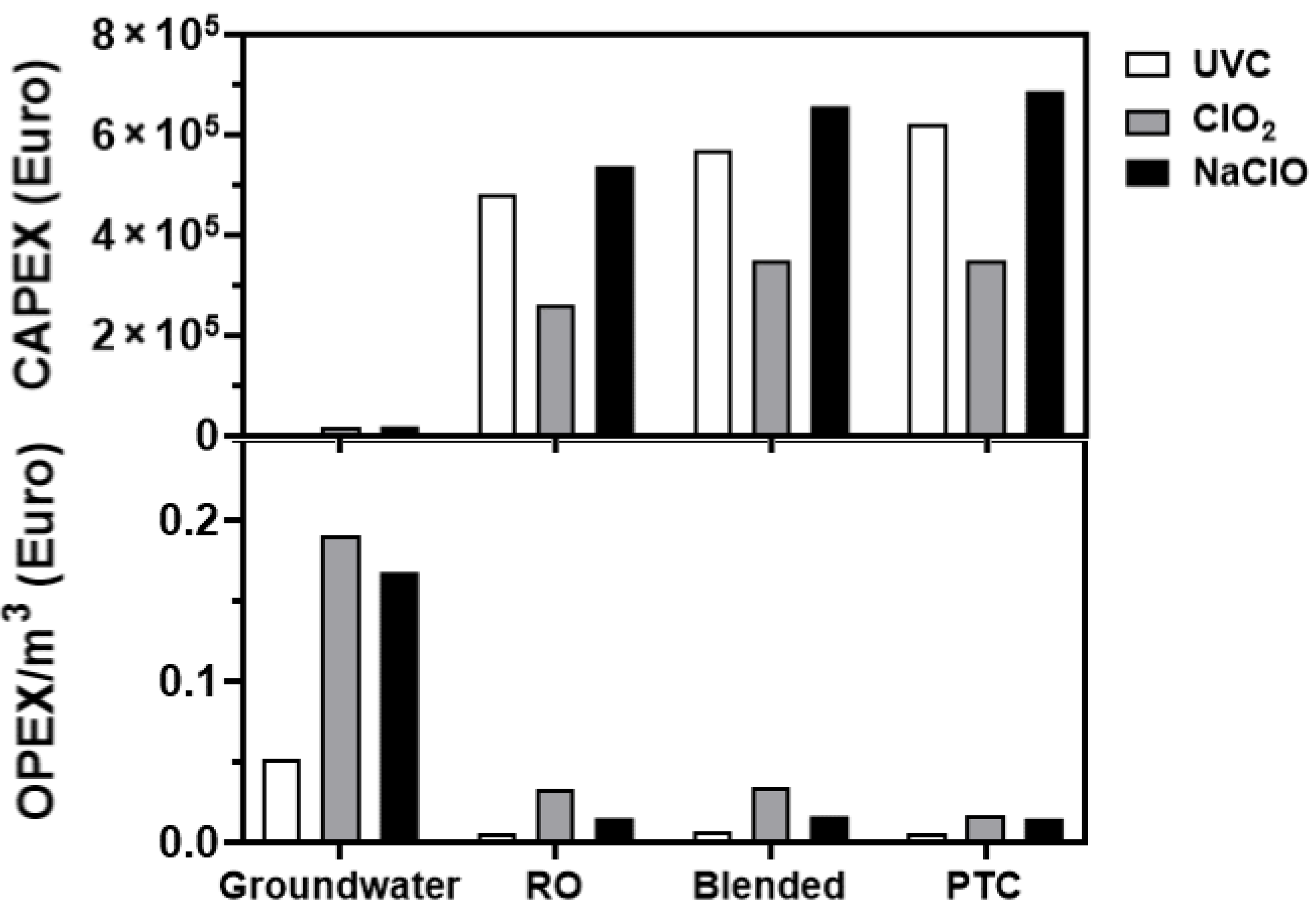

3.6. Cost Analyses

3.7. Feasibility Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Non-Chemical Disinfection

4.2. Chemical Disinfection

4.3. Feasibility Study Outcomes

5. Conclusions

- Of the non-chemical disinfection methods tested, UVC exerted a 4-fold stronger bactericidal activity than HC and was 2-fold more effective in the control of the E. coli load in deionised water than the control of the more resistant E. faecalis.

- Whilst HC failed to achieve a minimum of 2 Log10 inactivation for the tested strains under the set-ups employed in this work, it exerted additive E. coli- and synergistic E. faecalis-inactivation effects to UVC at 9.5 and 15 L/min flow rates and prolonged exposure, respectively.

- The synergistic E. faecalis-inactivation effect to UVC is attributed to HC-mediated oxygen radical generation contributing to oxidative stress that assisted disinfection lethality.

- TDS (9% change), and Ca2+ hardness (14% change) reduction, concomitantly followed the radical generation over prolonged contact times, indicating that HC is valuable for hybrid schemes with UVC, for both disinfection enhancement, inorganic/organic UVC-sleeve fouling, and water hardness control.

- Both physical disinfection technologies generated no toxic DBPs likely to compromise the organoleptic attributes of water. However, absence of stable long-lasting disinfection residual for delaying bacterial recovery, and extended exposure to the treatments, are disadvantageous over chemical inactivation.

- The significant CAPEX costs for implementation of UVC in the treatment of Maltese water, in addition to the infrastructural changes required for its accommodation, make adoption of UVC unlikely.

- ClO2 emerged as a better bactericidal than NaClO in the control of the tested bacteria in borehole water (alkaline pH), whereas NaClO disinfection was ideal in the treatment of RO water (closer-to-neutrality pH).

- ClO2-based borehole water disinfection was associated with chlorate production, whereas NaClO-based disinfection shared the same DBP repertoire with standard chlorination. However, the generated DBPs did not exceed the parametric values of the EU directive.

- The overall better disinfection propensity of NaClO (particularly in the control of E. faecalis-RO load) ranked the technology as the best alternative-to-chlorine-gas disinfection, despite its significant CAPEX costs, followed by ClO2.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stuart, M.E.; Maurice, L.; Heaton, T.H.E.; Sapiano, M.; Micallef-Sultana, M.; Gooddy, D.C.; Chilton, P.J. Groundwater residence time and movement in the Maltese islands—A geochemical approach. Appl. Geochem. 2010, 25, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartfiel, L.; Soupir, M.; Kanwar, R.S. Malta’s Water Scarcity Challenges: Past, Present, and Future Mitigation Strategies for Sustainable Water Supplies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloetscher, F.; Stambaugh, D.; Hart, J.; Cooper, J.; Kennedy, K.; Sher, L.; Ruffini, A.P.; Cicala, A.; Cimenello, S. Use of lime, limestone and kiln dust to stabilize reverse osmosis treated water. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 2013, 3, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Acceptability aspects: Taste, odour and appearance. In Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; Incorporating the First and Second Addenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 10. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK579463/ (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- McDonald, S.; Lethorn, A.; Loi, C.; Joll, C.; Driessen, H.; Heitz, A. Determination of odour threshold concentration ranges for some disinfectants and disinfection by-products for an Australian panel. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2493–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, W.; Yam, W.C.; Huang, H.; Leung, D.Y.C. The efficacy of vacuum-ultraviolet light disinfection of some common environmental pathogens. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Miino, M.C.; Caccamo, F.M.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C.; Sorlini, S. Disinfection of Wastewater by UV-Based Treatment for Reuse in a Circular Economy Perspective. Where Are We at? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Yang, J.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Blatchley, E.R., 3rd. UV-induced effects on toxicity of model disinfection byproducts. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hou, R.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J. Hydrodynamic cavitation as an efficient water treatment method for various sewage: A review. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaokar, G.S.; Khambete, A.K. Fuzzy rule base approach to evaluate performance of hydrodynamic cavitation for borewell water softening. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čehovin, M.; Medic, A.; Scheideler, J.; Mielcke, J.; Ried, A.; Kompare, B.; Žgajnar Gotvajn, A. Hydrodynamic cavitation in combination with the ozone, hydrogen peroxide and the UV-based advanced oxidation processes for the removal of natural organic matter from drinking water. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2017, 37, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, A.; Wu, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, L. Disinfection of bore well water with chlorine dioxide/sodium hypochlorite and hydrodynamic cavitation. Environ. Technol. 2015, 36, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanavaras, P.D.; Themelis, D.G.; Kika, F.S. Review of analytical methods for the determination of chlorine dioxide. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2007, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarotto, J.S.; Júnior, E.; Medeiros, R.C.; Volpatto, F.; Silvestri, S. Sanitary sewage disinfection with ultraviolet radiation and ultrasound. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11531–11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.X.; Ye, W.K.; Xu, B.; Hu, X.J.; Ma, S.X.; Lai, F.; Gao, Y.Q.; Xing, H.B.; Xia, W.H.; Wang, B. Comparison of UV-induced AOPs (UV/Cl2, UV/NH2Cl, UV/ClO2 and UV/H2O2) in the degradation of iopamidol: Kinetics, energy requirements and DBPs-related toxicity in sequential disinfection processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 398, 125570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Byun, S.; Jang, H.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.J. Comparison of disinfectants for drinking water: Chlorine gas vs. on-site generated chlorine. Environ. Eng. Res. 2021, 27, 200543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-T.; Lee, U.-G. Formation of chlorite and chlorate from chlorine dioxide with Han river water. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2004, 21, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzaki, S.; Urano, H.; Yamada, S. Effect of pH on the Efficacy of Sodium Hypochlorite Solution as Cleaning and Bactericidal Agents. J. Surf. Finish. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 58, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, W.J.; Jones, A.C.; Whitehead, R.F.; Zika, R.G. Sunlight-induced photochemical decay of oxidants in natural waters: Implications in ballast water treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3728–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; She, Q.; Cao, G.; Liu, Y.; Chang, V.W.; Tang, C.Y. Regulation, formation, exposure, and treatment of disinfection by-products (DBPs) in swimming pool waters: A critical review. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougé, V.; Allard, S.; Croué, J.-P.; von Gunten, U. In Situ Formation of Free Chlorine During ClO2 Treatment: Implications on the Formation of Disinfection Byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 13421–13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavonen, E.E.; Gonsior, M.; Tranvik, L.J.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Köhler, S.J. Selective chlorination of natural organic matter: Identification of previously unknown disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertova, A.; Miani, A.; Lesma, G.; Rondinini, S.; Minguzzi, A.; Falciola, L.; Ortenzi, M.A. Chlorine Dioxide Degradation Issues on Metal and Plastic Water Pipes Tested in Parallel in a Semi-Closed System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, I.A.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.O. Degradation analysis of polymeric pipe materials used for water supply systems under various disinfectant conditions. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougoutsa, C.; Christophoridis, C.; Zacharis, C.K.; Fytianos, K. Assessment, modeling and optimization of parameters affecting the formation of disinfection by-products in water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 16620–16630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Källén, B.A.; Robert, E. Drinking water chlorination and delivery outcome-a registry-based study in Sweden. Reprod. Toxicol. 2000, 14, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerrebroeck, R.; Horsten, T.; Stevens, C.V. Bromide Oxidation: A Safe Strategy for Electrophilic Brominations. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Study on the Disinfection Efficiency of the Combined Process of Ultraviolet and Sodium Hypochlorite on the Secondary Effluent of the Sewage Treatment Plant. Processes 2022, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Cang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Advantages of a ClO2/NaClO combination process for controlling the disinfection by-products (DBPs) for high algae-laden water. Environ. Geochem. Health 2019, 41, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand, J.L.; Gagnon, G.A. Loss of chlorine, chloramine or chlorine dioxide concentration following exposure to UV light. Aqua 2008, 57, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Covert, T.C.; Wild, D.K.; Berman, D.; Johnson, S.A.; Johnson, C.H. Comparative resistance of Escherichia coli and enterococci to chlorination. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Environ. Sci. Eng. Toxicol. 1993, 28, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artichowicz, W.; Luczkiewicz, A.; Sawicki, J.M. Analysis of the Radiation Dose in UV-Disinfection Flow Reactors. Water 2020, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bridges, D.F.; Lacombe, A.; Wu, V. Fundamental Differences in Inactivation Mechanisms of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Between Chlorine Dioxide and Sodium Hypochlorite. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 923964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrand, J.J.; Gröschel, D.H. Rapid, modified oxidase test for oxidase-variable bacterial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1982, 16, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geeraerd, A.H.; Valdramidis, V.P.; Van Impe, J.F. GInaFiT, a freeware tool to assess non-log-linear microbial survivor curves. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 102, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, I.; Mafart, P. A modified Weibull model for bacterial inactivation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 100, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, A.H.; Molva, C.; Unluturk, S. UV-C light inactivation and modeling kinetics of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores in white grape and apple juices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigelow, W.D.; Esty, J.R. The Thermal Death Point in Relation to Time of Typical Thermophilic Organisms. J. Infect. Dis. 1920, 27, 602–617. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i30082394 (accessed on 17 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Carratalà, A.; Ossola, R.; Bachmann, V.; Kohn, T. Cross-Resistance of UV- or Chlorine Dioxide-Resistant Echovirus 11 to Other Disinfectants. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M. Modeling the dynamic kinetics of microbial disinfection with dissipating chemical agents-a theoretical investigation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, A.; Randall, A.; Reinhart, D.; Daly, L. Effectiveness and kinetics of ferrate as a disinfectant for ballast water. Water Environ. Res. 2008, 80, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benarde, M.A.; Snow, W.B.; Olivieri, V.P.; Davidson, B. Kinetics and mechanism of bacterial disinfection by chlorine dioxide. Appl. Microbiol. 1967, 15, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.; Eaton, A.; Rice, E.; Bridgewater, L. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Footprint 2022. Country Specific Electricity Grid Greenhouse Gas Emission Factors. Available online: https://www.carbonfootprint.com/docs/2022_03_emissions_factors_sources_for_2021_electricity_v11.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simpson, A.; Ranade, V.V. Modelling of hydrodynamic cavitation with orifice: Influence of different orifice designs. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 136, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medir, M.; Giralt, F. Stability of chlorine dioxide in aqueous solution. Water Res. 1982, 16, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aieta, E.M.; Berg, J.D. A Review of Chlorine Dioxide in Drinking Water Treatment. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1986, 78, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noszticzius, Z.; Wittmann, M.; Kály-Kullai, K.; Beregvári, Z.; Kiss, I.; Rosivall, L.; Szegedi, J. Chlorine dioxide is a size-selective antimicrobial agent. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcon, J.; Mortha, G.; Marlin, N.; Molton, F.; Duboc, C.; Burnet, A. New insights into the decomposition mechanism of chlorine dioxide at alkaline pH. Holzforschung 2017, 71, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, I.N.; Francisco, J.S.; Margerum, D.W. New pathways for chlorine dioxide decomposition in basic solution. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 6500–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.M.C.; Lastra, J.M.P.; Andrés Juan, C.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Chlorine Dioxide: Friend or Foe for Cell Biomolecules? A Chemical Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborde, M.; von Gunten, U. Reactions of chlorine with inorganic and organic compounds during water treatment-Kinetics and mechanisms: A critical review. Water Res. 2008, 42, 13–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, W.; Ge, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, X. The reactions of chlorine dioxide with inorganic and organic compounds in water treatment: Kinetics and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 2287–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghernaout, D. Disinfection and DBPs removal in drinking water treatment: A perspective for a green technology. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Lantagne, D. Accuracy, precision, usability, and cost of free chlorine residual testing methods. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Roux, J.; Gallard, H.; Croué, J.P. Chloramination of nitrogenous contaminants (pharmaceuticals and pesticides): NDMA and halogenated DBPs formation. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3164–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, L.C.; Gordon, G. Hypochlorite Ion Decomposition: Effects of Temperature, Ionic Strength, and Chloride Ion. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.Q.; Lin, Y.L.; Xu, B.; Hu, C.Y.; Gao, Z.C.; Liu, Z.; Cao, T.C.; Gao, N.Y. Factors affecting the water odor caused by chloramines during drinking water disinfection. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, A.; Parraga Estrada, K.J.; Chhetri, V.S.; Janes, M.; Fontenot, K.; Beaulieu, J.C. Evaluation of ultraviolet (UV-C) light treatment for microbial inactivation in agricultural waters with different levels of turbidity. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucheli-Witschel, M.; Bassin, C.; Egli, T. UV-C inactivation in Escherichia coli is affected by growth conditions preceding irradiation, in particular by the specific growth rate. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollu, K.; Örmeci, B. UV-induced self-aggregation of E. coli after low and medium pressure ultraviolet irradiation. Photochem. Photobiology. B Biol. 2015, 148, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Andrés, J.; Romero-Martínez, L.; Acevedo-Merino, A.; Nebot, E. Determining disinfection efficiency on E. faecalis in saltwater by photolysis of H2O2: Implications for ballast water treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Chu, X.N.; Liu, L.; Hu, J.Y. Effects of salinity and temperature on inactivation and repair potential of Enterococcus faecalis following medium- and low-pressure ultraviolet irradiation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loraine, G.; Chahine, G.; Hsiao, C.T.; Choi, J.K.; Aley, P. Disinfection of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria using DynaJets ® hydrodynamic cavitating jets. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2012, 19, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupanc, M.; Kosjek, T.; Petkovšek, M.; Dular, M.; Kompare, B.; Širok, B.; Blažeka, Ž.; Heath, E. Removal of pharmaceuticals from wastewater by biological processes, hydrodynamic cavitation and UV treatment. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2013, 20, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Wang, T.; Wang, W.L.; Wu, Q.Y.; Li, A.; Hu, H.Y. UV/chlorine as an advanced oxidation process for the degradation of benzalkonium chloride: Synergistic effect, transformation products and toxicity evaluation. Water Res. 2017, 114, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdala, E.F.; Aquino, M.D.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Vidal, C.B.; do Nascimento, R.F.; de Sousa, F.W. Use of the cavitation hydrodynamics applied to water treatment. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2014, 19, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Watanabe, N.; Inomoto, K.; Kamitakahara, M.; Nakamura, K.; Komai, T.; Tsuchiya, N. Enhancement of aragonite mineralization with a chelating agent for CO2 storage and utilization at low to moderate temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Guo, W.; Lee, W. Formation of disinfection byproducts upon chlorine dioxide preoxidation followed by chlorination or chloramination of natural organic matter. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doederer, K.; Gernjak, W.; Weinberg, H.S.; Farré, M.J. Factors affecting the formation of disinfection by-products during chlorination and chloramination of secondary effluent for the production of high-quality recycled water. Water Res. 2014, 48, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shan, L.; Hu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhong, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J. Biofilm formation potential and chlorine resistance of typical bacteria isolated from drinking water distribution systems. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31295–31304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, K.E.; Reeves-McLaren, N.; Husband, S.; Boxall, J. Uncharted waters: The unintended impacts of residual chlorine on water quality and biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwatondo, M.H.; Silverman, A.I. Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. Indigenous to Wastewater Have Slower Free Chlorine Disinfection Rates than Their Laboratory-Cultured Counterparts. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venczel, L.V.; Likirdopulos, C.A.; Robinson, C.E.; Sobsey, M.D. Inactivation of enteric microbes in water by electro-chemical oxidant from brine (NaCl) and free chlorine. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gupta, V.; Shekhawat, S.S.; Kulshreshtha, N.M.; Gupta, A.B. A systematic review on chlorine tolerance among bacteria and standardization of their assessment protocol in wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofori, I.; Maddila, S.; Lin, J.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. Chlorine dioxide oxidation of Escherichia coli in water—A study of the disinfection kinetics and mechanism. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2017, 52, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virto, R.; Mañas, P.; Alvarez, I.; Condon, S.; Raso, J. Membrane damage and microbial inactivation by chlorine in the absence and presence of a chlorine-demanding substrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5022–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nocker, A.; Lindfeld, E.; Wingender, J.; Schulte, S.; Dumm, M.; Bendinger, B. Thermal and chemical disinfection of water and biofilms: Only a temporary effect in regard to the autochthonous bacteria. J. Water Health 2021, 19, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feasibility Areas | Questions | Answers | Assessment Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Implementation | 1. Can the technology be implemented given the current water characteristics? | Yes | 1 point |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Yes, with provisions 1 | 1–5 provisions (0.75 points) 6–10 provisions (0.5 points) 11–15 provisions (0.25 points) | ||

| 2. Practicality | 1. Is operation easy? | Yes | 1 point |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Yes, with provisions | 1–5 provisions (0.5 points) >5 provisions (0.25 points) | ||

| 2. Is installation easy? | Yes | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Yes, with provisions | 1–5 provisions (0.5 points) >5 provisions (0.25 points) | ||

| 3. Is operation occupationally safe? | Yes | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Yes, with provisions | 1–5 provisions (0.5 points) >5 provisions (0.25 points) | ||

| 4. Is dosing low on maintenance? | Yes | 1 point (≥1 advantage) | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| 3. Adaptability | 1. Does the technology offer flexibility? | Yes | 1 point (≥1 advantage) |

| No | 0 points | ||

| 2. Is the technology easily adaptable in a cost-effective manner? | Yes | 1 point (≥1 advantage) | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| 4. Integration | 1. Is the technology suitable for treatment of RO/blended water? | Yes | 1 point |

| Partly | 0.5 points (1 disadvantage) | ||

| No | 0 points (>1 disadvantage) | ||

| 2. Is the technology suitable for treatment of borehole water? | Yes | 1 point | |

| Partly | 0.5 points (1 disadvantage) | ||

| No | 0 points (> 1 disadvantage) | ||

| 3. Can the technology be combined with other technologies in hybrid schemes? | Yes | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Yes, with provisions | 1–5 provisions (0.75 points) 6–10 provisions (0.5 points) 11–15 provisions (0.25 points) | ||

| 4. Does the technology require specific chemical analyses techniques for monitoring? | Yes | 0 points (≥1 techniques) | |

| No | 1 point | ||

| 5. Environment and Sustainability | 1. How does the technology rank in terms of CO2 emissions? 2 | 1–3 ranks | 3 (1st), 2 (2nd), 1 (3rd) points |

| 4th rank | 0 points | ||

| 2. Is the technology more energy-efficient than gas chlorination? | Yes | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| 3. Would installation of the technology at the reservoir level pose additional environmental effects? | Yes | 0 points | |

| No | 1 point | ||

| 4. Would installation of the technology at the borehole level pose additional environmental effects? | Yes | 0 points | |

| No | 1 point | ||

| 5. Could the technology be powered by alternative energy means? | Yes | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points | ||

| 6. Cost and Effect | 1. Is application of the technology for RO/blended water fit for purpose (safe and clean water for consumption)? | Fully | 1 point |

| No | 0 points | ||

| Partly | 0.5 points | ||

| 2. Is application of the technology for borehole water fit for purpose (safe and clean water for consumption)? | Fully | 1 point | |

| No | 0 points (>2 disadvantages) | ||

| Partly | 0.5 points (2 disadvantage) | ||

| 3. In terms of microbial inactivation, how does the technology perform? | Total points from disinfection assessment | ||

| 4. In terms of by-products, is the technology likely to improve the water’s taste? | Yes | 1 point (1 DBP) | |

| Possibly | 0.5 points (Few DBPs) | ||

| No | 0 points (≥2 DBPs) | ||

| 5. How costly is application of the technology at RO level? | Total points from cost analysis | ||

| 6. How costly is application of the technology at borehole level? | Total points from cost analysis |

| Sample | p | δ (J/m2) | 4D (kJ/m2) | Log10(Nres) (cfu/mL) | R2 adj. | MSE | RMSE | STDEV of Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.24 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.56 ± 0.14 | 0.9803 | 0.1202 | 0.3467 | 0.3464 |

| E. faecalis | 0.34 ± 0.04 (0.0211) 1 | 10.4 ± 6.19 (n.s.) 1 | 0.63 ± 0.06 (0.0188) 1 | 1.08 ± 0.12 (0.0113) 1 | 0.9879 | 0.0581 | 0.2410 | 0.2390 |

| TBC (37 °C) | - | 82.0 ± 0.02 (0.0001) 2 | n.d. 3 | - | 0.9955 | 0.0365 | 0.1910 | 0.1915 |

| Water Source | Treatment | Dose (mg/L) | Organism | kdecay (Min−1) | kdisinfectant (mg−nLn Min−m) | Exposure Time for 4 Log10 Reduction (Min) | m | n | R 2 | Sy.X 1 | STDEV 1 | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blended | Cl2 | 1.1 | E. coli | 0.0001 | 6.76 ± 0.06 2 | 5.99 ± 0.39 2 | 0.146 | 0.512 | 0.9858 | 0.4945 | 0.4853 | 27 |

| 1.1 | E. faecalis | 0.0001 | 5.86 ± 0.06 | 15.84 ± 1.17 | 0.146 | 0.512 | 0.9837 | 0.4825 | 0.4735 | 27 | ||

| RO | ClO2 | 0.3 | E. coli | 0.001 | 3.44 ± 0.06 | 92.77 ± 3.74 | 0.420 | 0.761 | 0.9830 | 0.4947 | 0.4855 | 27 |

| 0.3 | E. faecalis | 0.001 | 2.47 ± 0.05 | 128.6 ± 8.47 | 0.300 | 0.117 | 0.9699 | 0.5462 | 0.5360 | 27 | ||

| 0.75 | E. coli | 0.0016 | 3.53 ± 0.06 | 58.21 ± 3.51 | 0.270 | 0.958 | 0.9786 | 0.5387 | 0.5286 | 27 | ||

| 0.75 | E. faecalis | 0.0016 | 4.85 ± 0.09 | 87.56 ± 8.00 | 0.180 | 0.559 | 0.9674 | 0.5521 | 0.5418 | 27 | ||

| NaClO | 0.3 | E. coli | 0.0026 | 6.31 ± 0.10 | 48.23 ± 3.91 | 0.197 | 0.319 | 0.9734 | 0.5959 | 0.5848 | 27 | |

| 0.3 | E. faecalis | 0.0026 | 7.98 ± 0.09 | 12.48 ± 0.79 | 0.187 | 0.319 | 0.9828 | 0.5700 | 0.5593 | 27 | ||

| 0.75 | E. coli | 0.0019 | 6.12 ± 0.08 | 28.85 ± 1.95 | 0.207 | 0.993 | 0.9794 | 0.5809 | 0.5700 | 27 | ||

| 0.75 | E. faecalis | 0.0019 | 8.19 ± 0.10 | 10.90 ± 0.70 | 0.187 | 1.13 | 0.9822 | 0.5969 | 0.5857 | 27 | ||

| Borehole | ClO2 | 0.3 | E. faecalis | 0.04 | 16.8 ± 0.23 | 49.66 ± 6.07 | 0.115 | 0.856 | 0.966 | 0.5393 | 0.5292 | 27 |

| 0.75 | E. faecalis | 0.0403 | 5.89 ± 0.09 | 55.67 ± 4.52 | 0.200 | 1.17 | 0.9704 | 0.5885 | 0.5775 | 27 | ||

| NaClO | 0.3 | E. faecalis | 0.0019 | 6.09 ± 0.08 | 47.94 ± 4.65 | 0.145 | 0.115 | 0.9729 | 0.5333 | 0.5233 | 27 | |

| 0.75 | E. faecalis | 0.0016 | 7.30 ± 0.08 | 40.34 ± 4.22 | 0.110 | 0.600 | 0.9767 | 0.4529 | 0.4444 | 27 |

| Treatments | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu Directive Value | Untreated Source | UVC1 (17 L/min) | UVC2 (14 L/min) | UVC3 (10 L/min) | UVC4 (6.5 L/min) | HC1 1 (17 L/min) | HC2 1 (14 L/min) | HC3 1 (10 L/min) | HC4 1 (6.5 L/min) | |

| Conductivity (mS/m) | - | 414 ± 41 | 414 ± 41 | 419 ± 42 | 412 ± 41 | 418 ± 42 | 418 ± 42 | 415 ± 42 | 412 ± 41 | 410 ± 41 |

| TOC 2 | no abnormal change | 0.81 ± 0.16 | 0.98 ± 0.20 | 1.08 ± 0.22 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 1.01 ± 0.20 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 1.72 ± 0.34 |

| CaCO3 hardness 2 | - | 630 | 678 | 661 | 655 | 660 | 628 | 603 | 587 | 627 |

| Ca2+ hardness 4 | - | 3.27 | 3.46 | 3.29 | 3.33 | 3.46 | 3.23 | 3.15 | 3.10 | 3.25 |

| Nitrates 2 | 50 | 49.2 ± 7.4 | 46.9 ± 7.0 | 47.3 ± 7.1 | 47.3 ± 7.1 | 47.5 ± 7.1 | 44.8 ± 6.7 | 44.7 ± 6.7 | 47.2 ± 7.1 | 46.7 ± 7.0 |

| Nitrites 2 | 0.5 | <0.30 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 |

| Calcium 2 | - | 131 ± 13 | 139 ± 14 | 132 ± 13 | 134 ± 13 | 139 ± 14 | 129 ± 13 | 126 ± 13 | 124 ± 12 | 130 ± 13 |

| Magnesium 2 | - | 73.6 ± 7.4 | 80.7 ± 8.1 | 80.8 ± 8.1 | 78.3 ± 7.8 | 76.2 ± 7.6 | 74.2 ± 7.4 | 69.9 ± 7.0 | 67.2 ± 6.7 | 73.5 ± 7.4 |

| Chloride 2 | 250 | 1220 ± 183 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | n.m. 3 | 1260 ± 189 | 1270 ± 191 | 1150 ± 173 | 1140 ± 171 |

| Chemical | EU Directive Value | Untreated Source | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClO2 (0.3 ppm) | ClO2 (0.75 ppm) | In Situ NaClO (0.3 ppm) | In Situ NaClO (0.75 ppm) | |||

| Sum of chlorate and chlorite (mg/L) | ≤0.25 natively; ≤0.7 when ClO2 applied | <0.13 | 0.26 | 0.62 | <0.13 | <0.13 |

| Sum of 4 THMs (µg/L) | 100 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 1.28 | 8.98 | 17.8 |

| Dichloroacetonitrile | - | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 0.20 |

| Dibromoacetonitrile | - | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 0.50 | 0.40 |

| Sum of 9 HAAs (µg/L) | - | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 42.2 |

| Sum of chloroacetic acids | - | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 29.1 |

| Sum of 5 HAAs (µg/L) | 60 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 34.7 |

| Chloramines | - | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.07 |

| Chlorate (µg/L) | 250 | <80 | 259 ± 52 | 615 ± 123 | <80 | 94 ± 19 |

| Nitrite (mg/L) | 0.50 | <0.30 | <0.30 | <0.30 | <0.30 | <0.30 |

| Nitrate (mg/L) | 50 | 45.2 ± 6.8 | 45.8 ± 6.9 | 45.6 ± 6.8 | 45.6 ± 6.8 | 45.7 ± 6.9 |

| Antimony (µg/L) | 10 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| Arsenic (µg/L) | 10 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 |

| Boron (mg/L) | 1.5 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| Cadmium (µg/L) | 5.0 | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 |

| Calcium (mg/L) | - | 124 ± 12 | 125 ± 13 | 127 ± 13 | 129 ± 13 | 126 ± 13 |

| Chromium (µg/L) | 25 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| Copper (mg/L) | 2.0 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 |

| Iron (µg/L) | - | 35.9 ± 3.6 | 46.1 ± 4.6 | 46.3 ± 4.6 | 45.8 ± 4.6 | 47 ± 4.7 |

| Lead (µg/L) | 5.0 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.6 |

| Manganese (µg/L) | 50 | 2.78 ± 0.3 | 2.98 ± 0.3 | 3.45 ± 0.4 | 3.05 ± 0.3 | 3.06 ± 0.3 |

| Magnesium (mg/L) | - | 66.9 ± 6.7 | 67.6 ± 6.8 | 67.6 ± 6.8 | 68.8 ± 6.9 | 69.2 ± 6.9 |

| Mercury (µg/L) | 1.0 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 |

| Nickel (µg/L) | 20 | 8.6 ± 0.9 | 10.7 ± 1.1 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 10.2 ± 1.0 |

| Selenium (µg/L) | 20 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 | n.m. 1 |

| Sodium (mg/Lt) | 200 | 503 ± 50 | 523 ± 52 | 510 ± 51 | 520 ± 52 | 511 ± 51 |

| Question | Implementation | Practicality | Adaptability | Integration | Environment and Sustainability | Cost and Effect | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 5.1 4 | 5.2 5 | 5.3 6 | 5.4 7 | 5.5 8 | 6.1 9 | 6.2 | 6.3 10 | 6.4 | 6.5 12 | 6.6 13 | Total | |

| UVC | 0.5 (10) 1 | 1 | 0.5 (3) | 0.5 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 (1) | 0 | 0.75 (3) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 (2) | 17 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 31.25 |

| ClO2 | 0.5 (10) | 0.5 (1) | 0.5 (4) | 0.5 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 2 | 0.75 (3) | 0 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 (1) | 20 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 33.75 |

| NaClO | 0.25 (11) | 0.5 (1) | 0.5 (5) | 0.5 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.75 (3) | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 (2) | 26 | 0.5 11 | 1 | 0 | 37.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Psakis, G.; Spiteri, D.; Mallia, J.; Polidano, M.; Rahbay, I.; Valdramidis, V.P. Evaluation of Alternative-to-Gas Chlorination Disinfection Technologies in the Treatment of Maltese Potable Water. Water 2023, 15, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15081450

Psakis G, Spiteri D, Mallia J, Polidano M, Rahbay I, Valdramidis VP. Evaluation of Alternative-to-Gas Chlorination Disinfection Technologies in the Treatment of Maltese Potable Water. Water. 2023; 15(8):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15081450

Chicago/Turabian StylePsakis, Georgios, David Spiteri, Jeanice Mallia, Martin Polidano, Imren Rahbay, and Vasilis P. Valdramidis. 2023. "Evaluation of Alternative-to-Gas Chlorination Disinfection Technologies in the Treatment of Maltese Potable Water" Water 15, no. 8: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15081450

APA StylePsakis, G., Spiteri, D., Mallia, J., Polidano, M., Rahbay, I., & Valdramidis, V. P. (2023). Evaluation of Alternative-to-Gas Chlorination Disinfection Technologies in the Treatment of Maltese Potable Water. Water, 15(8), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15081450