An Interpretable CatBoost Model Guided by Spectral Morphological Features for the Inversion of Coastal Water Quality Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

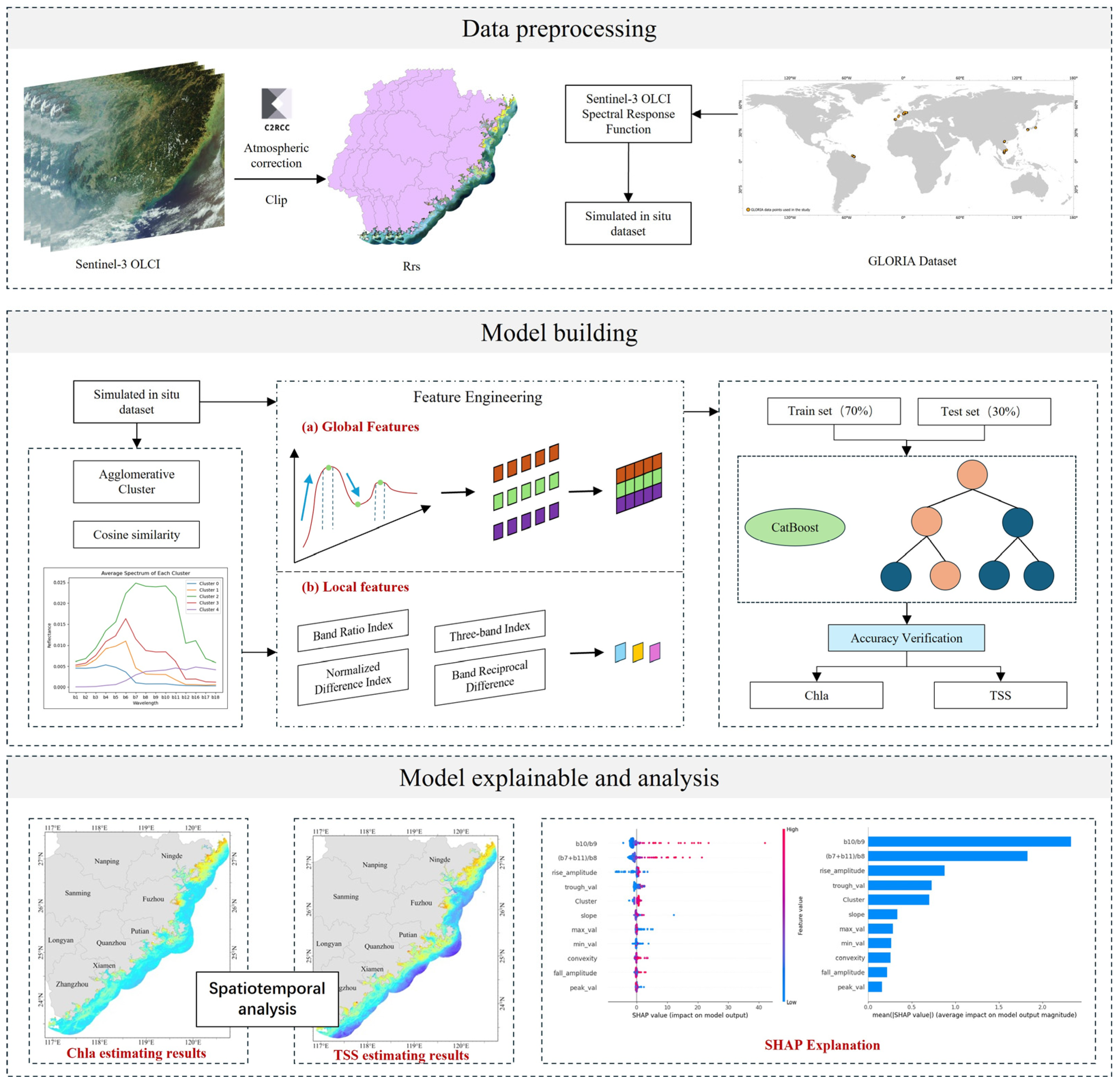

2. Study Area and Data Preprocessing

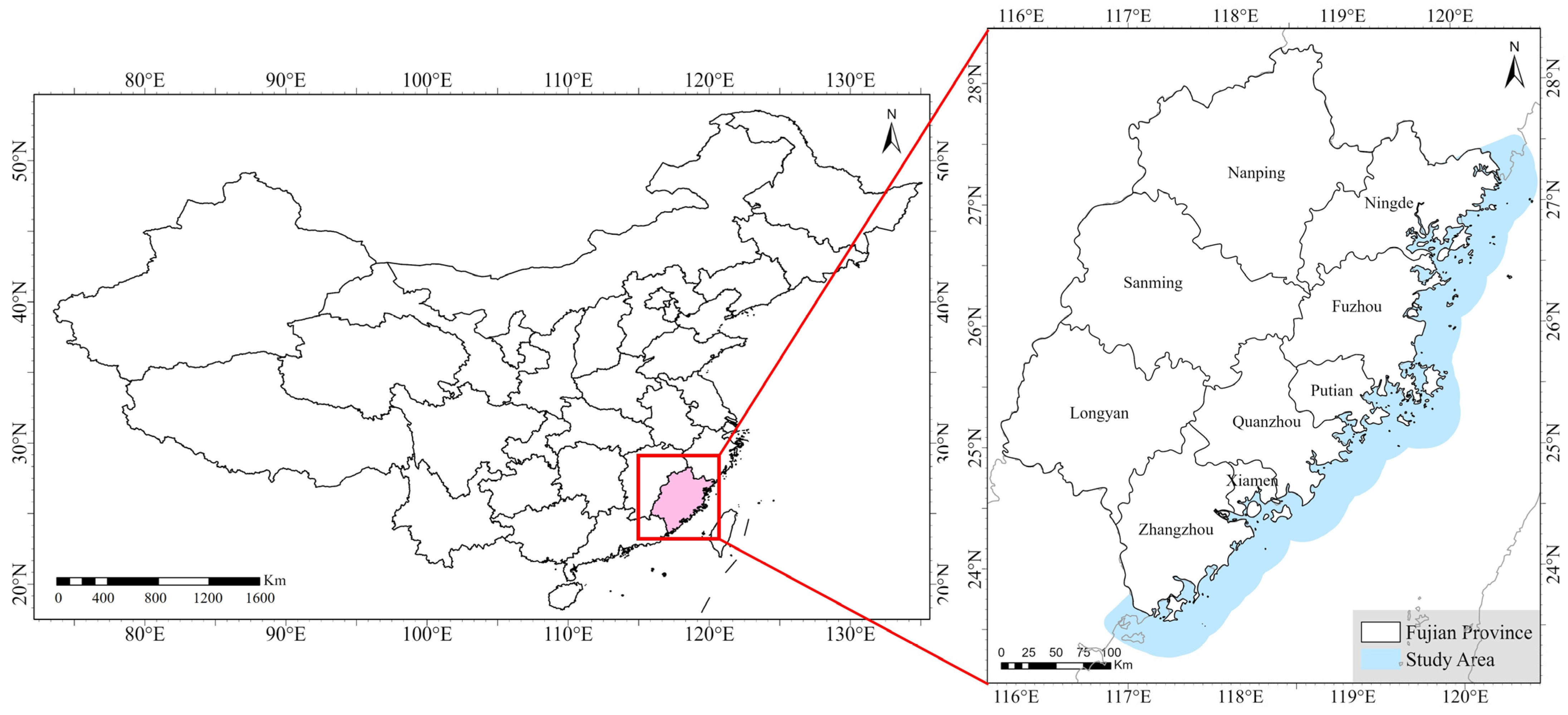

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sentinel-3 OLCI Data Processing

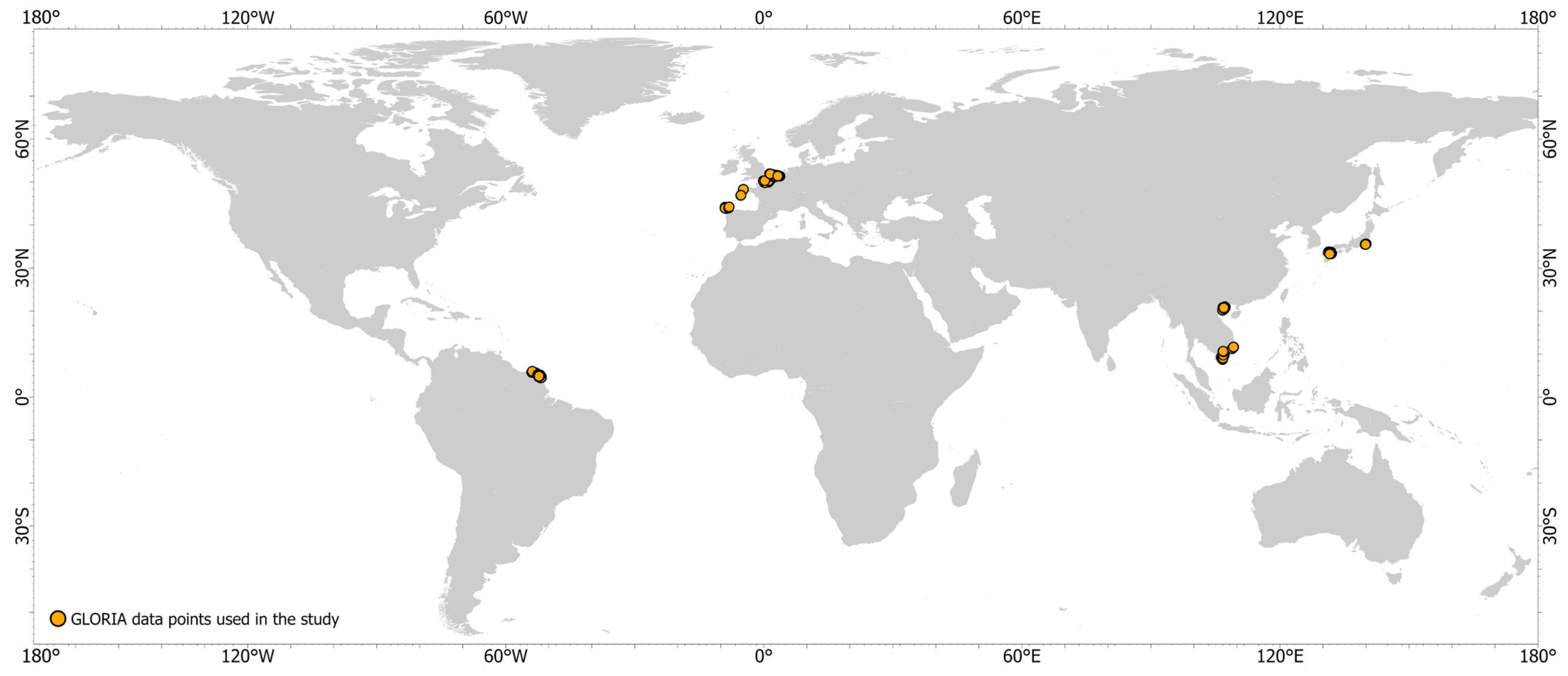

2.3. GLORIA Dataset Simulates in Situ Data

3. Methods

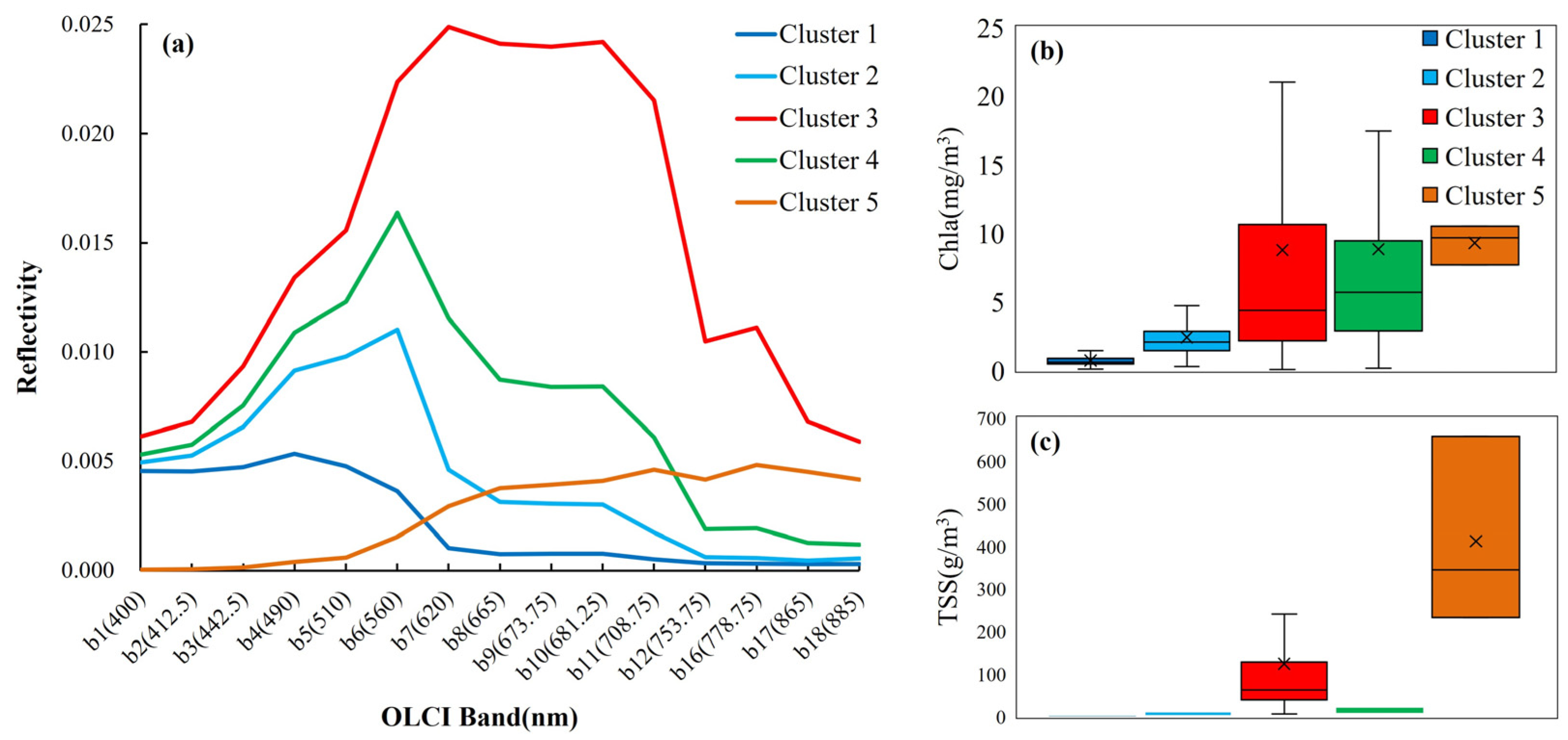

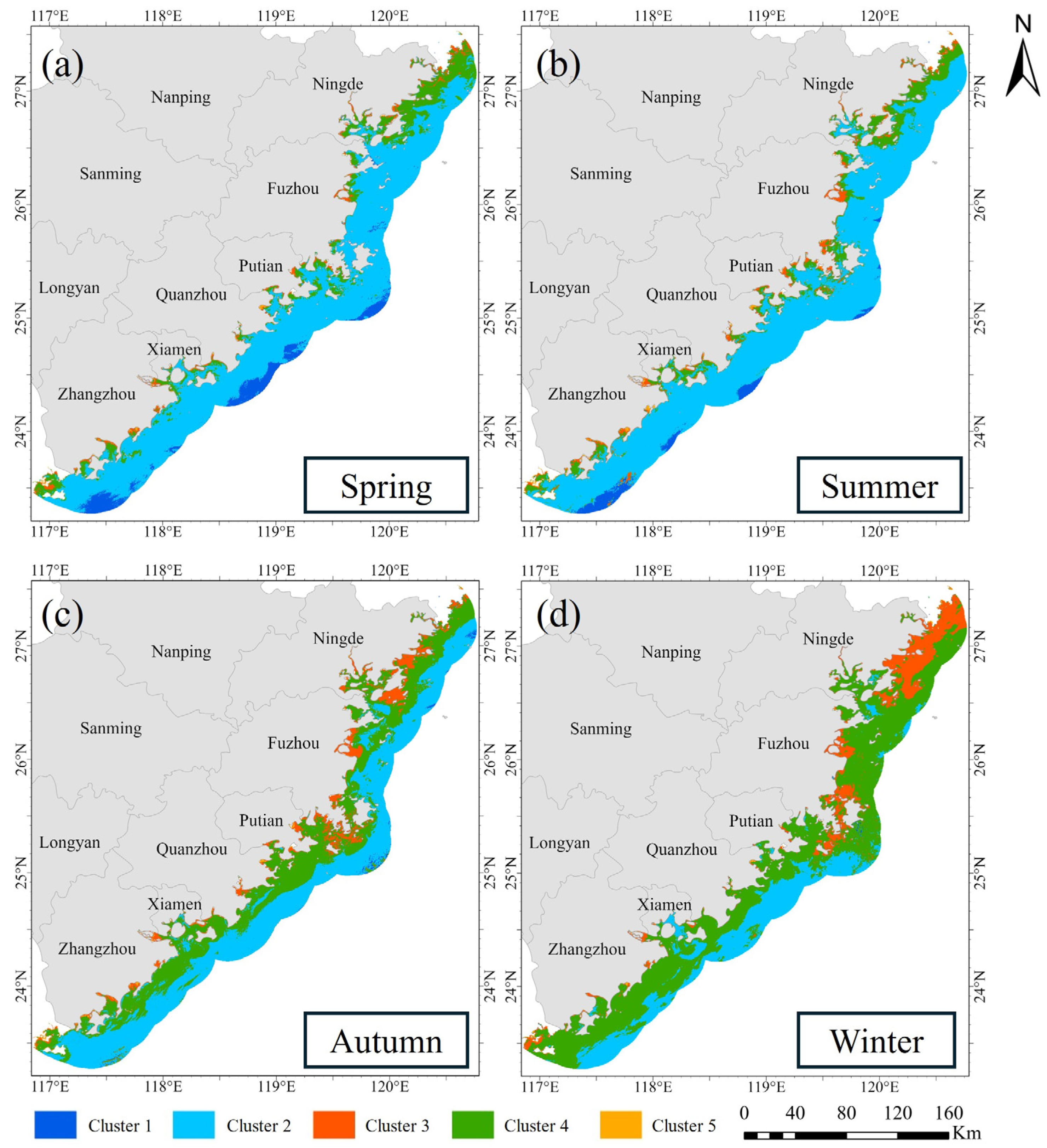

3.1. Water Spectral Classification

3.2. Model Building

3.2.1. Feature Engineering

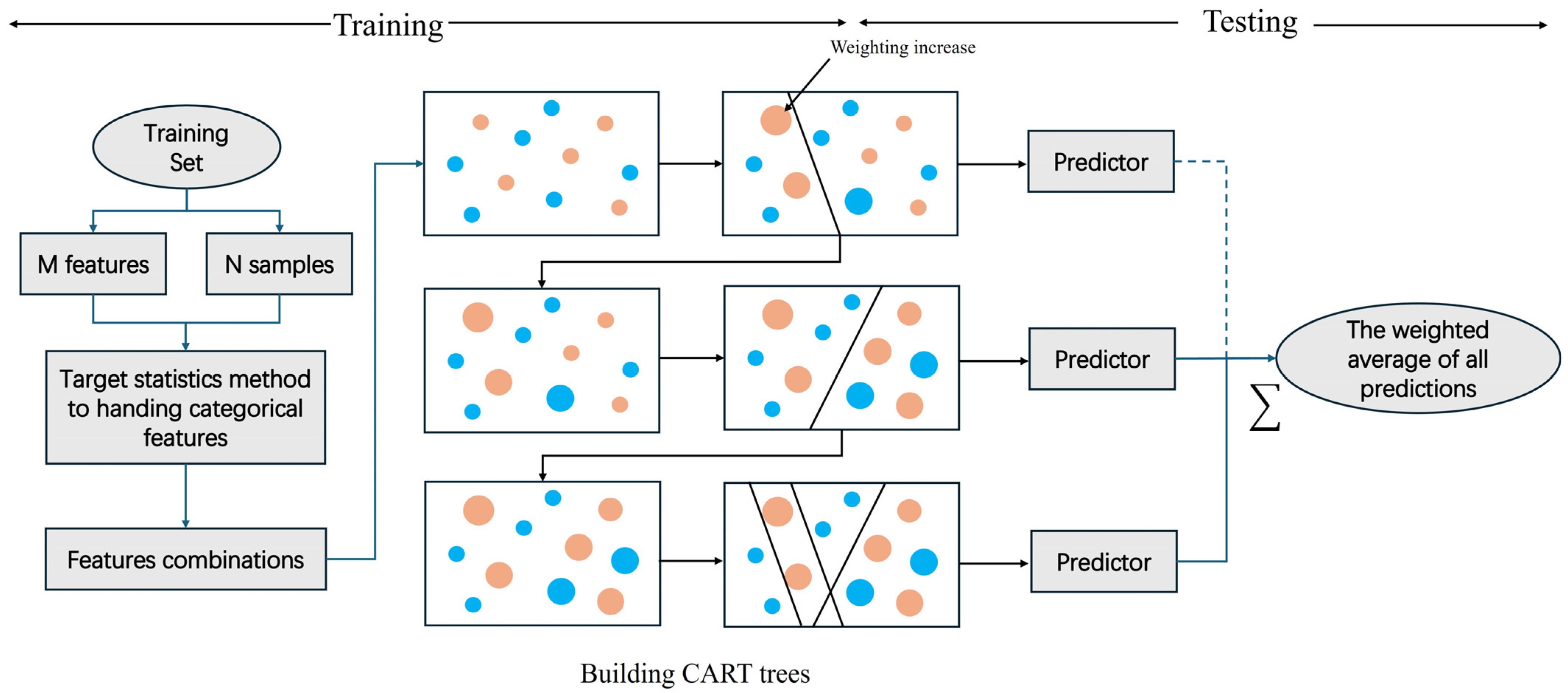

3.2.2. CatBoost

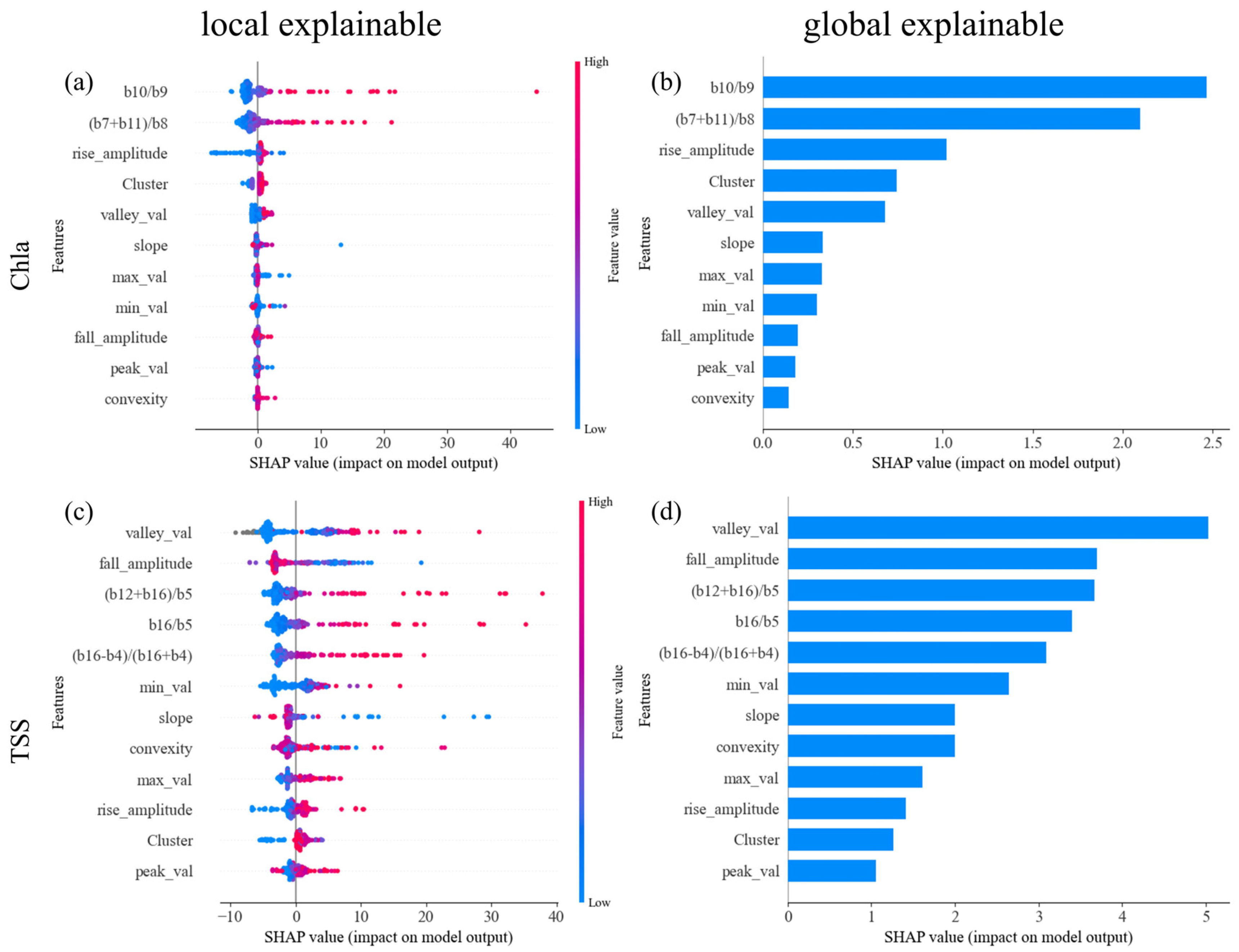

3.3. Model Interpretation by SHAP Model

4. Results and Discussion

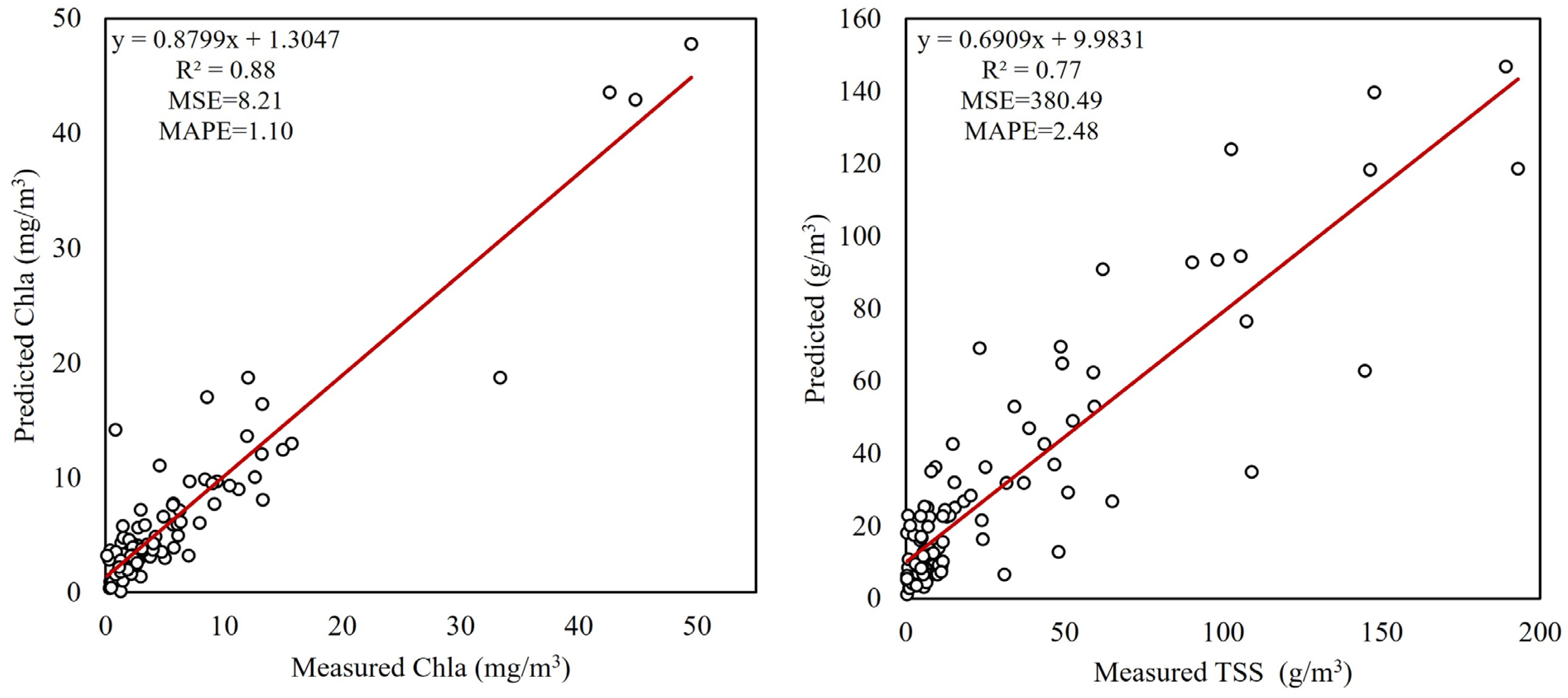

4.1. Model Accuracy and Explanation

4.2. Chla and TSS Inversion Using OLCI

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, N.D.; Megonigal, J.P.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Bailey, V.L.; Butman, D.; Canuel, E.A.; Diefenderfer, H.; Ganju, N.K.; Goñi, M.A.; Graham, E.B. Representing the function and sensitivity of coastal interfaces in Earth system models. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, T.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, Y. Assessing ecological risks caused by human activities in rapid urbanization coastal areas: Towards an integrated approach to determining key areas of terrestrial-oceanic ecosystems preservation and restoration. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, D.; Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Guan, B.; Wang, X.; Zhan, C.; Wang, Z.; Qu, F. Environmental threats induced heavy ecological burdens on the coastal zone of the Bohai Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Gu, W. Macroalgal blooms caused by marine nutrient changes resulting from human activities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Hasan, H.A.; Othman, A.R.; Ismail, N.I. Aquaculture industry: Supply and demand, best practices, effluent and its current issues and treatment technology. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottet, A.; George, C.; Drillet, G.; Lauro, F.M. Aquaculture in coastal urbanized areas: A comparative review of the challenges posed by Harmful Algal Blooms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 2888–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, X.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, X.; Li, Q.; Su, J.; Ittekkot, V. Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Wei, J.; Mu, B.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, X. Remote sensing of chlorophyll a concentration in turbid coastal waters based on a global optical water classification system. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 163, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Matsushita, B.; Pahlevan, N.; Gurlin, D.; Lehmann, M.K.; Fichot, C.G.; Schalles, J.; Loisel, H.; Binding, C.; Zhang, Y. Remotely estimating total suspended solids concentration in clear to extremely turbid waters using a novel semi-analytical method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberioon, M.; Brom, J.; Nedbal, V.; Souček, P.; Císař, P. Chlorophyll-a and total suspended solids retrieval and mapping using Sentinel-2A and machine learning for inland waters. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezonik, P.L.; Bouchard, R.W., Jr.; Finlay, J.C.; Griffin, C.G.; Olmanson, L.G.; Anderson, J.P.; Arnold, W.A.; Hozalski, R. Color, chlorophyll a, and suspended solids effects on Secchi depth in lakes: Implications for trophic state assessment. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Alikas, K.; Anstee, J.; Barbosa, C.; Binding, C.; Bresciani, M.; Cremella, B.; Giardino, C.; Gurlin, D. Simultaneous retrieval of selected optical water quality indicators from Landsat-8, Sentinel-2, and Sentinel-3. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Peng, Y.; Jia, K.; Hicks, B.J. Remote sensing big data for water environment monitoring: Current status, challenges, and future prospects. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, S.; Tiwari, S.P. Modeling ocean surface chlorophyll-a concentration from ocean color remote sensing reflectance in global waters using machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Shi, K.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Chena, X.; Zheng, F. Assessment of NIR-red algorithms for observation of chlorophyll-a in highly turbid inland waters in China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 93, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurlin, D.; Gitelson, A.A.; Moses, W.J. Remote estimation of chl-a concentration in turbid productive waters—Return to a simple two-band NIR-red model? Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 3479–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fang, L.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Huang, W. Evaluation of a three-band model for estimating chlorophyll-a concentration in tidal reaches of the Pearl River Estuary, China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.; Xue, Y. Remote sensing evaluation of total suspended solids dynamic with Markov model: A case study of inland reservoir across administrative boundary in South China. Sensors 2020, 20, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Zha, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, M. A Landsat 8 OLI-based, semianalytical model for estimating the total suspended matter concentration in the slightly turbid Xin’anjiang Reservoir (China). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, N.A.; Hoa, P.V.; Thao, G.T.P.; Duan, H.D.; Thu, P.M. Evaluation of Chlorophyll-a estimation using Sentinel 3 based on various algorithms in southern coastal Vietnam. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Li, Y.; Zha, Y.; Sun, D.; Huang, C.; Lu, H. A four-band semi-analytical model for estimating chlorophyll a in highly turbid lakes: The case of Taihu Lake, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Qin, B. Monitoring water quality using proximal remote sensing technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, C. Urban river water quality monitoring based on self-optimizing machine learning method using multi-source remote sensing data. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Du, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, F. Water quality Chl-a inversion based on spatio-temporal fusion and convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Jacinthe, P.A.; Liu, G.; Li, S.; Shang, Y.; Tao, H.; Fang, C.; Lyu, L. Remote estimates of suspended particulate matter in global lakes using machine learning models. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X. Knowledge-guided mixture density network for chlorophyll-a retrieval and associated pixel-by-pixel uncertainty assessment in optically variable inland waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhang, K.; Bagheri, M.; Burken, J.G.; Gu, A.; Li, B.; Ma, X.; Marrone, B.L.; Ren, Z.J.; Schrier, J.; et al. Machine learning: New ideas and tools in environmental science and engineering. Environ. Sci. 2021, 55, 12741–12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Lu, D. Developing a New Method to Rapidly Map Eucalyptus Distribution in Subtropical Regions Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Forests 2024, 15, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Park, J.; Zhao, K.; Londo, A.; Khanal, S. Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms and Water Quality Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Satellite Imagery with Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, C.; Doerffer, R.; Peters, M.; Kerstin, S.; Embacher, S.; Ruescas, A. Evolution of the C2RCC neural network for Sentinel 2 and 3 for the retrieval of ocean colour products in normal and extreme optically complex waters. In Proceedings of the Living Planet Symposium, Prague, Czech Republic, 9 May 2016; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Doerffer, R.; Schiller, H. The MERIS Case 2 water algorithm. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Wu, W. Estimating coastal chlorophyll-a concentration from time-series OLCI data based on machine learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, F.; Hunt, B.P.; Jacoby, D.; Costa, M. Performance of OLCI Sentinel-3A satellite in the Northeast Pacific coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.K.; Gurlin, D.; Pahlevan, N.; Alikas, K.; Anstee, J.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Barbosa, C.C.F.; Binding, C.; Bracher, A.; Bresciani, M.; et al. GLORIA-A globally representative hyperspectral in situ dataset for optical sensing of water quality. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, R.; Shen, F.; Liu, J. HY-1C/D CZI image atmospheric correction and quantifying suspended particulate matter. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, Y.; Bi, S.; Lei, S.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Zeng, S.; Lyu, H. Urban water quality assessment based on remote sensing reflectance optical classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gu, M.; Gong, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; He, Z. An advanced remote sensing retrieval method for urban non-optically active water quality parameters: An example from Shanghai. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, M.; Um, T.-W.; Khan, A.; Khan, U. Automatic detection system of olive trees using improved K-means algorithm. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.W.; Minallh, N.; Ahmad, N.; Abid, S.A.R.; Khan, M.A.A. K-Means and ISODATA clustering algorithms for landcover classification using remote sensing. Sindh Univ. Res. J.-SURJ 2016, 48, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhai, Q. Improved k-means and spectral matching for hyperspectral mineral mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 91, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.R.; Blömer, J.; Kuntze, D.; Sohler, C. Analysis of agglomerative clustering. Algorithmica 2014, 69, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. Learning similarity with cosine similarity ensemble. Inf. Sci. 2015, 307, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Cui, T.; Runa, A.; Pan, X.; Zhao, W.; Xiang, J.; Cao, M. Robust remote sensing retrieval of key eutrophication indicators in coastal waters based on explainable machine learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tian, S.; Huang, J.J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z. Performance of deep learning in mapping water quality of Lake Simcoe with long-term Landsat archive. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 183, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Reiter, M.; Munyei, N. Estimation of chlorophyll-a concentrations in diverse water bodies using ratio-based NIR/Red indices. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2017, 6, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoto, J.; Blanco, A.; Argamosa, R.; Medina, J. Pasig river water quality estimation using an empirical ordinary least squares regression model of Sentinel-2 satellite images. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 46, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.; Gad, M.; Farouk, M.; Saleh, A.H.; Hussein, H.; Elmetwalli, A.H.; Elsherbiny, O.; Moghanm, F.S.; Moustapha, M.E.; Taher, M.A. Using optimized two and three-band spectral indices and multivariate models to assess some water quality indicators of Qaroun Lake in Egypt. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, E.M.L.M.; Steffen, C.A.; Braga, C.Z.F. Results of a laboratory experiment relating spectral reflectance to total suspended solids. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 36, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 6637–6647. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhou, H. Evaluation of CatBoost method for prediction of reference evapotranspiration in humid regions. J. Hydrol. 2019, 574, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Fu, B.; Li, S.; Lao, Z.; Deng, T.; He, W.; He, H.; Chen, Z. Monitoring multi-water quality of internationally important karst wetland through deep learning, multi-sensor and multi-platform remote sensing images: A case study of Guilin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Explainable heat-related mortality with random forest and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrina, G.D.; Duarte, L.T.; Grabisch, M. A k-additive Choquet integral-based approach to approximate the SHAP values for local interpretability in machine learning. Artif. Intell. 2023, 325, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S.; Nie, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Hao, F.; Fu, H.Y. Monitoring of chlorophyll-a and suspended sediment concentrations in optically complex inland rivers using multisource remote sensing measurements. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, R.E.; Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Boss, E.; Gurlin, D.; Alikas, K.; Kangro, K.; Kudela, R.M.; Vaičiūtė, D. A hyperspectral inversion framework for estimating absorbing inherent optical properties and biogeochemical parameters in inland and coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Wu, Q.; Liu, P.; Hu, W.; Huang, B.; Shi, B.; Zhou, Y.; Kwon, B.-O.; Choi, K.; Ryu, J. Ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments and water from the coastal areas of the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, G.; Peng, M.; Wei, A.; Zhao, Y.; Soetaert, K. Unraveling seasonal and interannual nutrient variability shows exceptionally high human impact in eutrophic coastal waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2023, 68, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, H.; Huang, J.J.; Tian, S.; Zhang, Z. A hybrid decomposition and Machine learning model for forecasting Chlorophyll-a and total nitrogen concentration in coastal waters. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Duan, H.; Feng, L.; Ma, R.; Xue, K. Climate-and human-induced changes in suspended particulate matter over Lake Hongze on short and long timescales. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Combination | Expression | Chla | Expression | TSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRI | 0.69 | 0.73 | ||

| BRD | 0.41 | 0.32 | ||

| NDI | 0.68 | 0.70 | ||

| TBI | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| Parameters | Ranges | Optimal Values |

|---|---|---|

| iterations | [1, +∞] | 1000 |

| learning_rate | [0, 1] | 0.01 |

| depth | [1, +∞] | 3 |

| loss_function | RMSE, Logloss, MAPE, Poisson | RMSE |

| l2_leaf_reg | [1, +∞] | 1 |

| Factor | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chla (mg/m3) | Average value | 7.93 | 6.75 | 9.31 | 8.65 |

| Standard deviation | 2.61 | 1.81 | 3.67 | 3.45 | |

| TSS (g/m3) | Average value | 46.45 | 35.55 | 56.85 | 51.56 |

| Standard deviation | 13.75 | 14.59 | 14.30 | 13.67 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H. An Interpretable CatBoost Model Guided by Spectral Morphological Features for the Inversion of Coastal Water Quality Parameters. Water 2024, 16, 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16243615

Chen B, Chen Y, Chen H. An Interpretable CatBoost Model Guided by Spectral Morphological Features for the Inversion of Coastal Water Quality Parameters. Water. 2024; 16(24):3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16243615

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Baofeng, Yunzhi Chen, and Hongmei Chen. 2024. "An Interpretable CatBoost Model Guided by Spectral Morphological Features for the Inversion of Coastal Water Quality Parameters" Water 16, no. 24: 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16243615

APA StyleChen, B., Chen, Y., & Chen, H. (2024). An Interpretable CatBoost Model Guided by Spectral Morphological Features for the Inversion of Coastal Water Quality Parameters. Water, 16(24), 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16243615