Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries

Highlights

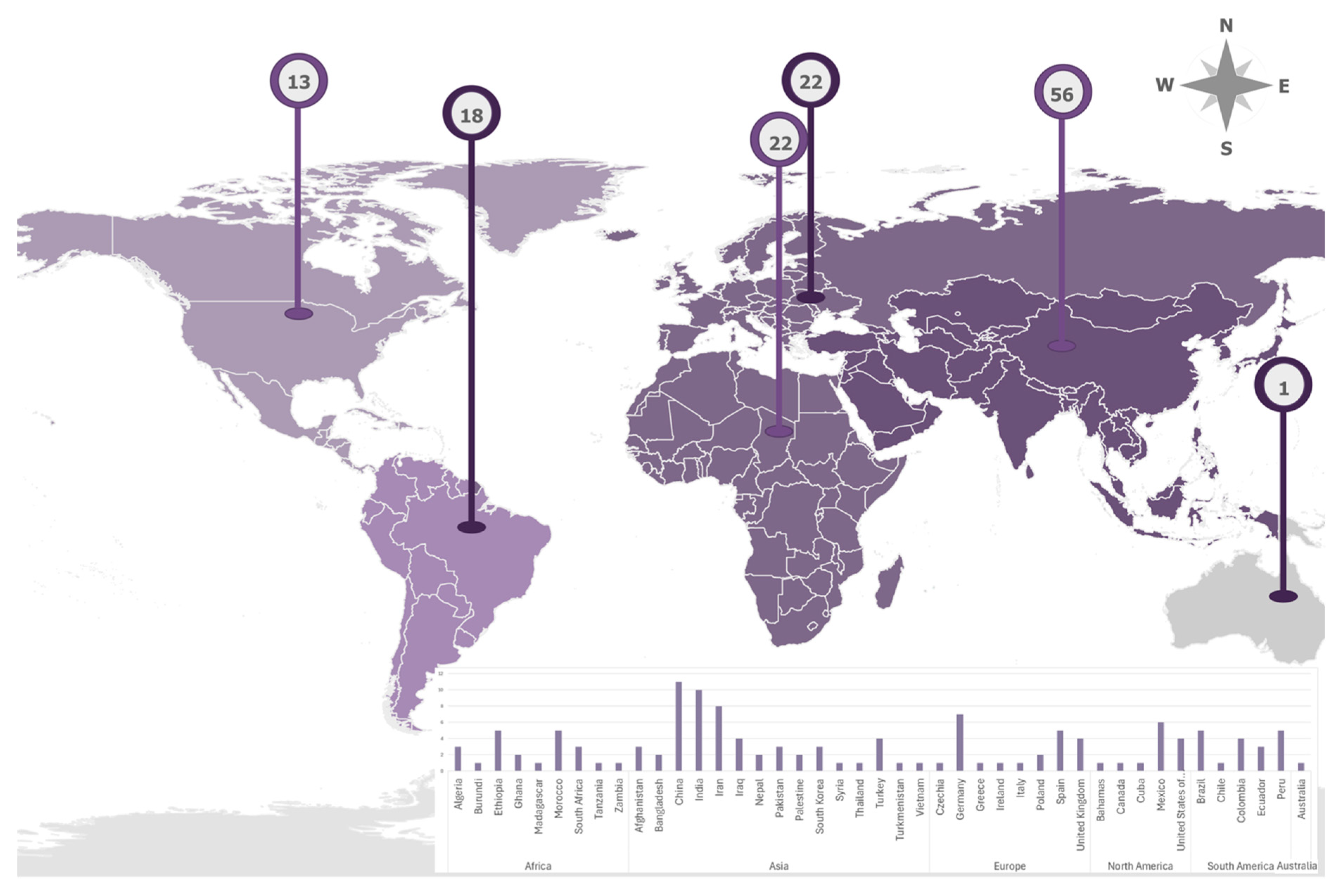

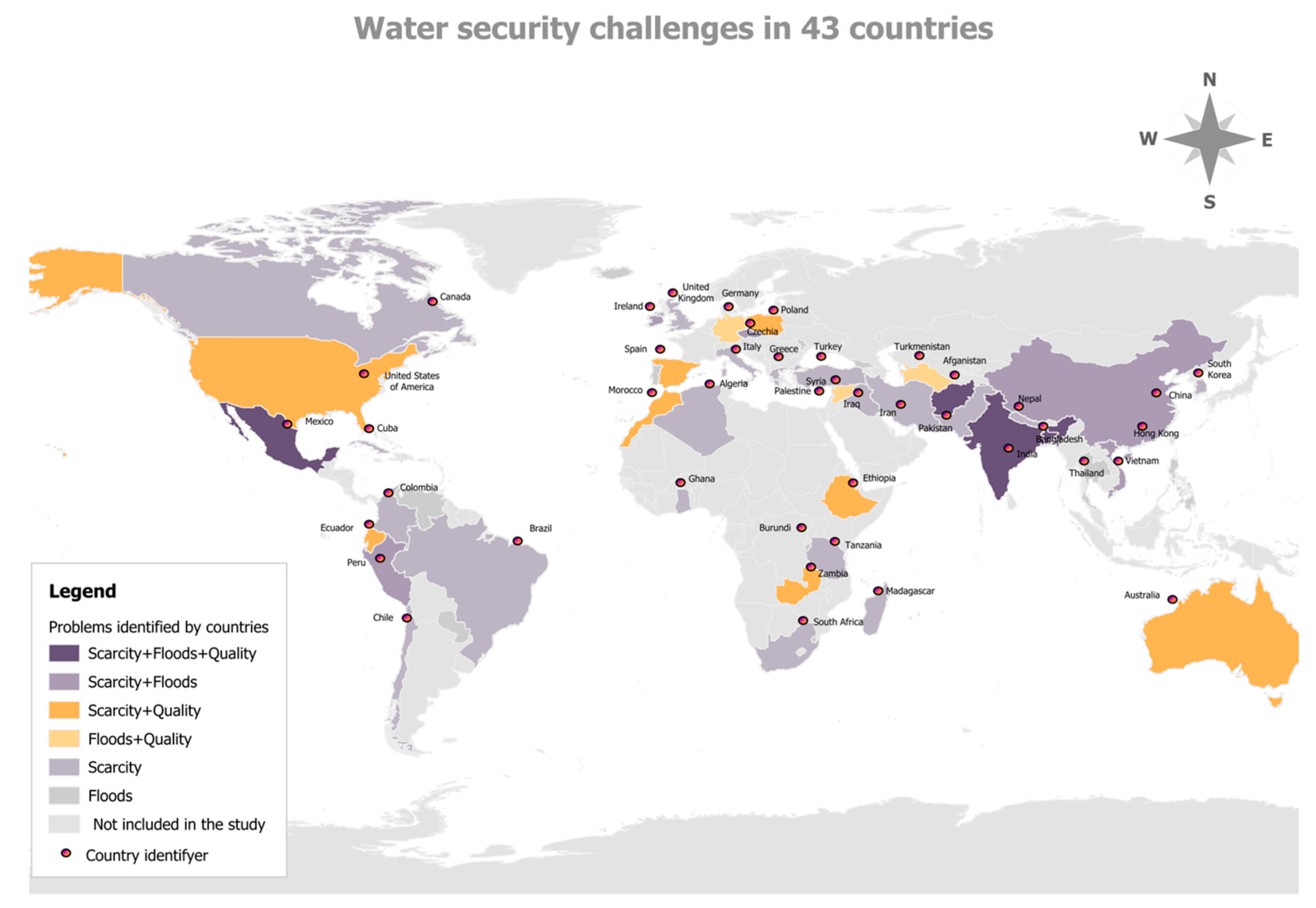

- Managing water-related natural hazards is a significant challenge in all of the countries analyzed.

- Climate change altered the hydrological cycle, leading to significant changes in precipitation and water storage.

- This study identified flash floods, drought, and water quality as the main water security issues.

- It was found that countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, and Mexico are among the most severely affected.

- Sustainable urban planning, improved efficiency, and predictive technology are key strategies that can be employed to boost water security.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Climate change is one of the main catalyzers compromising water security. In this regard, the changes observed over the last decade, including rising temperatures and alterations throughout the hydrological cycle, have intensified the study of water-related issues such as scarcity, floods, and pollution.

- Due to climate variability, spatial and temporal changes in water security issues can occur rapidly, making previously gathered information obsolete in a short period. This can be due to the implementation of solutions to address the problem or because the situation has worsened.

- Territorial Specificity: Only articles that address water security issues within defined national or watershed boundaries were included.

- Data Homogeneity: To prevent bias from regions with extensive publication records, a maximum of eleven articles per country was established. This ensured a more equitable geographical representation.

- Currency and Relevance: When more than eleven relevant articles were identified per country, priority was given to the most recent publications and those articles covering different watersheds to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the water security challenges.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Water Security and Climate Change

3.2. Challenges in Water Security by Regions and Countries

- Scarcity: Algeria [78,79]; Bahamas [10]; Brazil [9,80,81,82,83]; Canada [84]; Chile [85]; Colombia [86,87,88]; Cuba [89]; Ghana [90,91]; Greece [14]; Iran [92,93,94,95,96,97]; Iraq [98,99,100,101]; Italy [102]; Madagascar [103]; Nepal [21,104]; Pakistan [105,106,107]; Palestine [108,109]; South Africa [110,111,112]; South Korea [113,114,115]; Tanzania [116]; Turkey [11,117,118]; United Kingdom [119].

3.3. Response Measures to Guarantee Water Security

3.3.1. Sustainable Urban Planning

3.3.2. Improving Consumption Efficiency

- Adapt water distribution policies to address future demands, guaranteeing adequate water supply for both human consumption and agricultural production, which are essential for food security and economic development [15].

- Introducing improvements in water use efficiency is essential to reduce the vulnerability of communities severely affected by extreme weather events [118,127]. Implementing adjustments in the allocation and use of water across key sectors, such as agriculture and urban consumption, promotes more efficient resource management. This approach helps mitigate the impact of supply shortages [11] and encourages the adoption of measures aimed at ensuring the long-term sustainability of available resources [16], tailored to the specific needs of each productive sector, including agriculture [104,116]. Agricultural water demand can be reduced by applying new irrigation technologies to minimize water losses [101]. The complementarity between rain and irrigation can be a strategy to optimize water use in agriculture [57].

- Transitioning water management from a demand-driven to a supply-driven approach is essential in regions facing water scarcity. Effective water resource management must align with the actual availability of water [128]. Optimizing water use based on both needs and availability is crucial for ensuring long-term water security, particularly during periods of reduced supply [89].

- Implement water-saving policies [40] and promote sustainable agricultural practices, such as planned irrigation and watershed management, to optimize water use in agriculture [26]. Furthermore, it is crucial to invest in water management technologies, such as desalination and artificial recharge, to ensure the future availability of drinking water [10], while promoting the use of deficit irrigation techniques [92].

- Water leakage control involves identifying the main sources of water loss, such as high evapotranspiration, and developing resource management strategies to optimize water use and minimize losses [15,56], for example, a sprinkler irrigation system can improve the annual volume required [49]. Key measures include maintaining infrastructure and adopting more efficient technologies [14,30,47,69,89]. These initiatives can be supported by public and private funding for infrastructure and technology advances aimed at enhancing irrigation efficiency [62,106], for example, improving network performance and the use of desalination [78].

- Reuse of water in irrigation areas as a strategy to maximize the use of available resources. This practice not only helps preserve water but also supports the supply for agricultural activities during periods of low availability [89].

3.3.3. Strategic Land-Use Planning

3.3.4. Applying Technologies to Predict and Monitor Variations in Resource Availability

3.3.5. Planning Based on Temporal Resource Variations

3.3.6. Developing Disaster Containment Infrastructure

3.3.7. Creating Storage Infrastructure

3.3.8. Enhancing Groundwater Use

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Regions | Countries | Water Problems | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Algeria | Water scarcity is intensifying due to population growth, climate change, and urbanization. Reduced rainfall, inefficient irrigation, and over-reliance on groundwater resources exacerbate deficits, threatening agricultural productivity and aquifer recharge rates. | Bessedik et al. [78]; Boudjebieur et al. [79] |

| Burundi | Water insecurity is driven by flood risks stemming from changes in runoff patterns and extreme flow events. These changes impact water availability, seasonal distribution, and agricultural production. | Kim et al. [120] | |

| Ethiopia | Agricultural expansion and climate change intensify water scarcity, impacting agro-food systems, water balance, and sustainability of irrigation. In Ethiopia, the Awash River Basin faces severe water quality issues due to untreated wastewater and agricultural runoff. | Flint et al. [21]; Abera and Ayenew [56]; Kidanewold et al. [57]; Gedefaw and Denghua [58]; Abate et al. [59] | |

| Ghana | The average rainfall over the entire basin is projected to increase in the wet season [July to December] and will be not enough in the dry season [January to June]. Population growth, climate change, and land-use changes, coupled with rising temperatures, are expected to induce water scarcity by 2050, threatening food production and key crops. | Amisigo et al. [90]; Abungba et al. [91] | |

| Madagascar | Despite its high potential for freshwater availability, Madagascar remains vulnerable to water scarcity. Factors such as climate change, land use and cover changes, population growth, and existing policies significantly affect water resources and the livelihoods of communities residing near major river basins. | Zy et al. [103] | |

| Morocco | Land-use changes, including the expansion of agricultural and urban areas, are impacting negatively on water quality and availability of both surface and groundwater. Additional challenges include erosion, biodiversity loss and deficiencies in irrigation technology, all of which place greater pressure on the situation by adding the effects of climate variability. | Gallardo-Cruz et al. [35]; Ben et al. [60]; Nevárez-Favela and Fernández-Reynoso [61]; Andrade et al. [62]; Alitane et al. [63] | |

| South Africa | Current and future limited water supply capacity and availability have the greatest impact on regions such as the Eastern Cape and parts of Mpumalanga, with predictions to exacerbate with climate pattern variability. Additionally, dams and reservoirs are unable to effectively capture and manage projected rainfall increases due to inadequate water storage infrastructure. | Cullis [110]; Vernon et al. [111]; Dlamini et al. [112] | |

| Tanzania | The combined effects of climate change and rising water demand are expected to create a critical water security challenge, especially in the Pangani basin. While projected increases in precipitation may enhance water availability during certain seasons, they are unlikely to be sufficient to meet the growing demands of the agricultural, hydroelectric, and domestic sectors. | Kishiwa et al. [116] | |

| Zambia | The high demand for irrigation water, particularly in the upper and middle sections of the basin, combined with a historical decline in precipitation and elevated evapotranspiration levels, results in severe water shortages, especially during dry seasons. Furthermore, the reduction in aquifer recharge and surface flow, along with the discharge of wastewater from treatment plants, affects water quality and the long-term sustainability of the resource. | Tena et al. [75] | |

| Asia | Afghanistan | The country is facing high vulnerability, low reliability, and limited resilience, especially in the Kabul River basin. Projections suggest that climate change will increase runoff variability, altering precipitation patterns, and amplifying surface runoff, raising the frequency and severity of droughts and floods. As a consequence, water production is projected to fall short of meeting demand. | Saka and Mohammady [15]; Sediqi and Komori [16]; Akhtar et al. [22] |

| Bangladesh | Water insecurity affects parts of the country, with projections indicating a worsening trend, especially in the north-west region with the highest demand increase. This raises concerns regarding unsustainable groundwater use if appropriate management strategies are not implemented. While irrigation water demand is expected to rise in the coming decades, it may subsequently decline due to improved crop yields and population decreases. Vulnerability to both floods and groundwater contamination is projected to increase across both dry seasons and the monsoon climate system, characterized by heavy rainfall. | Raihan et al. [17]; Kirby and Mainuddin [23] | |

| China | Water security risks exhibit significant regional variations, with challenges related to water availability, quality, and climate risks like droughts and floods. While some areas manage resources effectively, others face severe water security deficits. Rising water scarcity, driven by increased demand from urban, economic, agricultural, and industrial sectors, and intensive mining activities have depleted groundwater storage. In densely populated regions, water quality fluctuates significantly, with agricultural runoff and wastewater as primary contaminants. Despite these challenges, positive trends have been observed, such as the Yangtze River Basin’s water security index improving from “unsafe” in 2011 to “relatively safe” by 2019, and similar positive trends in Inner Mongolia and Gansu. | Zhou et al. [1]; Li et al. [2]; Chunxia and Yiqiu [5]; Tang et al. [12]; Deng et al. [40]; Sun et al. [41]; Zhang et al. [42]; Gu et al. [43]; Zhang et al. [44]; Wang et al. [45] | |

| Hong Kong (China) | The region has experienced significant flood events, largely attributable to its natural topography, which limits flood management to a five-year recurrence interval. Historical floods have had a severe impact on Shenzhen and Hong Kong, disrupting local economies and the daily lives of residents. Recurrent flooding of the Shenzhen River has further adversely affected infrastructure, local economies, and communities in both cities. | Yang and Huang [121] | |

| India | Key challenges to water security include low rainfall, high temperatures, and consistently high evaporation rates, exacerbated by inadequate water storage infrastructure. Urbanisation has further reduced pond areas and groundwater recharge volumes. Sub-basins are particularly vulnerable to soil erosion and sedimentation. Projections indicate increased flood vulnerability due to elevated river flow and runoff, influenced by variations in precipitation amount, frequency, and intensity. Additionally, water demand is expected to far exceed supply, posing significant risks to water security. Increased runoff and reduced aquifer recharge exacerbate these issues, impacting water availability for both human consumption and agricultural use. | Ishita and Kamal [24]; Pandi et al. [25]; Sabale et al. [26]; Kumar et al. [27]; Dubey et al. [29]; Nivesh et al. [30]; Jayanthi et al. [31]; Loukika et al. [32] | |

| Iran | Current scenarios reveal that water demand exceeds the available capacity, posing significant risks to agricultural production and urban water supply and the projections are not favourable due to reduction in precipitation and water reservoir, presenting more frequent periods of water scarcity. Groundwater availability is in play due to overexploitation from the three main aquifers and intensive land use. Additionally, climate change is accelerating snowmelt, which, combined with increased evaporation, is contributing to long-term reductions in water availability for storage and use. | Shaabani et al. [92]; Najimi et al. [93]; Moghadam et al. [94]; Sheikha-Bagem et al. [95]; Zare et al. [96]; Salmani et al. [97] | |

| Iraq | Water shortages have been identified due to transboundary retention caused by the Upstream dam construction and water loss of surface irrigation systems. Additionally, population growth, along with industrial and agricultural expansion, has made it increasingly difficult to meet the rising demand for water. Also, the evapotranspiration in a specific period exceeds the system’s capacity to deliver water to meet demands and water availability has been affected with the reduction of flow of the Euphrates River from Turkey, combined with the limited storage capacity. | Hamdi et al. [98]; Saeed et al. [99]; Najm et al. [100]; Abdulhameed et al. [101] | |

| Nepal | Flood risks in the Karnali River basin are significant. Projections indicate a considerable increase in river flow, which, while potentially enhancing water availability, also presents significant risks, notably an elevated potential for flooding and challenges in managing increased water volumes during rainy seasons. Rising minimum and maximum temperatures are expected to accelerate glaciers and snow melt, further altering the basin’s hydrological cycle. Additionally, reliable water sources in Nepal are diminishing due to reduced precipitation and accelerated glacier melt. | Flint et al. [21]; Lamichhane et al. [104] | |

| Pakistan | Water distribution within the basin is unequal, with significant challenges in agricultural areas that are heavily dependent on irrigation. Urban and industrial areas also face persistent water shortages. High unmet water demand is projected, driven by factors such as population growth, agricultural expansion, climate change, and a substantial reduction in water availability. Rising temperatures, reductions in precipitation and increased evaporation rates are expected to further reduce the flow of the Indus and the Kabul basins. | Waqas et al. [105]; Amin et al. [106]; Khalid and Saleem [107] | |

| Palestine | Limited water resource availability and overexploitation, combined with geopolitical challenges, significantly restrict access to additional water supplies. The region exhibits a high degree of vulnerability to both natural and anthropogenic risks, which are further intensified by increasing climate pressures, urbanisation, ongoing conflicts, and a deficit of investment in modern water management infrastructure. | Jabari et al. [108]; Jabari et al. [109] | |

| South Korea | Surface runoff increases, induced by changes in urban area extent and agricultural practices within the catchment, coupled with reduced groundwater recharge and evapotranspiration, suggest a shift in the water balance dynamics. Projections suggest an increase in the frequency and intensity of both meteorological and hydrological droughts, driven by declining precipitation during key seasons and rising temperatures. | Ware et al. [113]; Kim et al. [114]; Lee et al. [115] | |

| Syria | Water availability challenges are driven by rapid population growth, leading to a significant decline in per capita water resources. This situation is expected to worsen under the impacts of climate change, with decreased precipitation, reduced runoff, and diminished flow in the Euphrates River, the region’s main water supply. | Mourad and Alshihabi [76] | |

| Thailand | Water security varies unevenly across different regions. Some areas are expected to see increased water levels, while others may experience reductions. During dry season, rainfall is projected to rise by up to 84%, while increases of up to 11% are anticipated during the wet season. While these precipitation changes could enhance water availability at certain times, they also elevate the risk of extreme events, such as flooding. Such flooding is expected to impact rice paddies, intercropped plantations, and urbanised areas, posing significant challenges for both water management and land use planning. | Satriagasa et al. [122] | |

| Turkey | Projected climate change and population growth impacts on future water availability suggest that the basin is likely to face water shortages driven by both climatic factors and rising demand, particularly from agriculture, the region’s largest water consumer. This includes the prospect of water shortages during dry periods and excessive flows in the wet season. Furthermore, groundwater has been compromised due to overexploitation and changes in recharge capacity. | Yaykiran [11]; Keleş [117]; Taylan [118] | |

| Turkmenistan | Climate change is expected to introduce greater seasonal variability, resulting in severe floods during wet seasons and reduced flow in the Harirud River throughout most seasons. These changes are likely to decrease water quality due to increased nutrient loads, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, and diffuse pollution from untreated agricultural wastewater. The construction of the Salma Dam in Afghanistan has further reduced downstream water flow, significantly impacting water availability in Iran and Turkmenistan. Moreover, the Doosti Reservoir, which supplies water to Mashhad in Iran, is projected to fail in meeting water demand beyond 2036, leading to critical water security challenges for the region. | Nazari [77] | |

| Vietnam | Base flow reduction during the dry season with significant challenge for water availability and Increased runoff during the rainy season with flood risks in downstream urban areas. | Ha and Bastiaanssen [52] | |

| Europe | Czechia | Alterations in land use and agricultural practices have significantly altered the small water cycle, increasing surface runoff and diminishing infiltration, resulting in sedimentation, water scarcity, and localised flooding. These effects are expected to intensify with anticipated increases in temperature and variability in precipitation patterns. | Noreika et al. [39] |

| Germany | Water security risks are primarily focused on the management of extreme events, such as flooding. Deforestation and land use change contribute to water quality degradation, as increased runoff transports higher levels of sediments, nutrients, and pollutants into rivers. This negatively impacts water quality for human consumption, agriculture, and other uses. Furthermore, annual river flows have risen by more than 80%, further compounding water management challenges. | Shukla et al. [4] | |

| Greece | Under the baseline scenario, the Ali Efenti basin faces a significant unmet annual water demand, principally driven by the agricultural sector, its largest water consumer. Simulations of deficit irrigation practices suggest significant potential for annual water savings. Within the urban, tourism, and industrial sectors, one scenario projects further water savings through enhanced distribution network efficiency and a reduction in water losses. | Psomas et al. [14] | |

| Ireland | Climate variability in combination with land cover change amplifies the hydrological response, resulting in more pronounced extremes in both dry and wet conditions. The increasing rate of urbanisation and its alterations in land cover have contributed to the rising frequency of extreme floods and their associated devastations. | Basu et al. [46] | |

| Italy | Significant droughts in the last few years, rising water stress for crops and the ecosystem in general, increase in the number of rain but reduction in overall precipitation. | Bernini et al. [102] | |

| Poland | The economy is heavily reliant on agriculture, where intensive farming practices and climate change are exacerbating water stress, resulting in years with low average precipitation average, classified as “dry” according to the Relative Precipitation Index [RPI]. Furthermore, reservoir water quality is severely compromised by pollution from agricultural activities. | Zlati et al. [64]; Szewczyk et al. [65] | |

| Spain | Water security challenges include water shortages and groundwater overexploitation. Heavily reliant on groundwater for drinking water, agriculture, and drought mitigation in major cities such as Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia, the country faces significant challenges. Hotspots of pronounced groundwater overexploitation include the Upper Guadiana Basin and several basins in Andalusia, where inadequate groundwater management and structural issues exacerbate the problem. In south-eastern Spain, a region experiencing chronic water scarcity, the environmental impacts of blue water consumption for energy crops are particularly severe. Climate change and environmental flow requirements are expected to significantly reduce hydroelectric power production. Under low-adaptation scenarios, the most severe impacts on water security include increased plant water stress, higher flood discharge, hillside erosion, and increased sediment yield. The implementation of more efficient irrigation techniques and adopting Nature-based Solutions [NbS] could reduce water demand. | Gunn and Amelin [66]; Núñez et al. [67]; Garcia et al. [68]; Eekhout et al. [69]; Cheng et al. [70] | |

| United Kingdom | The area is currently facing water security deficits, with demand exceeding supply. This situation is expected to worsen, particularly during the summer months, due to annual increases in demand. These challenges are most acute downstream of the River Dee, notably in cities such as Chester. | Abbas et al. [119] | |

| North America | Bahamas | Water security is unevenly distributed across the island, with some areas facing greater risks than others. The study predicts that risks in Andros will intensify by the end of the century, driven by the combined effects of climate change and population growth. | Holding and Allen [10] |

| Canada | This region is susceptible to severe droughts due to low annual precipitation and the geographic influence of barriers such as the Rocky Mountains. Over recent decades, a 1.7 °C increase in average annual temperature has exacerbated water stress. With 58% of the land dedicated to agriculture, fluctuations in soil moisture and recurrent droughts present significant challenges to regional food security. Projections suggest a future increase in both frequency and severity of agriculture problems. | Zare et al. [84] | |

| Cuba | Extreme drought events during 2011–2012 and 2015–2016 severely reduced water availability. Future decreases in precipitation, driven by climate variability and change, are expected to further compromise water availability, posing significant challenges to agricultural sustainability. Agricultural activities, particularly rice cultivation, remain the primary consumers of water resources. Projections indicate increasing pressures on water resources due to declining precipitation and increasing demand. | Puebla et al. [89] | |

| Mexico | There is a high vulnerability to contamination, water scarcity, and flooding. Insufficient wastewater treatment capacity, inadequate flood protection infrastructure, and inefficient water distribution systems exacerbate issues of water access and quality, negatively affecting overall water security. The conversion of natural areas into agricultural lands has further increased water demand, putting additional strain on water availability. Furthermore, projections indicate an increase in mean annual temperature and a decrease in precipitation due to climate change, leading to more frequent extreme events. These changes are expected to exacerbate water scarcity in certain regions seasonally and elevate the risk of seasonal flooding. | Cortez-Mejía et al. [33]; De La Rosa et al. [34]; Gallardo-Cruz et al. [35]; Leija et al. [36]; Colín-García et al. 37]; Molina-Sánchez and Chávez-Morales [38] | |

| United States of America | Mountain regions experience recurring drought conditions, notably during dry seasons (e.g., East-Taylor in Colorado). Increases in temperature and shifting precipitation, patterns snowmelt leading to increases in stational soil dryness and increases in overall surface runoff from the topographical smoothening. In the Upper Colorado River Basin, there are issues related to water quality and limited availability due to specific disturbances such as wildfires, extreme rainfall, and debris flows. Increased food production is also uncertain as the irrigated area in water-stressed regions is increasing, especially in Southwest United States. | Mital et al. [71]; Edvard [72]; Ridgway et al. [73]; Kompas et al. [74] | |

| South America | Brazil | Water insecurity is exacerbated by groundwater contamination stemming from inadequate sanitation infrastructure. Under global warming scenarios exceeding 1.5 °C, increased evapotranspiration and decreased precipitation are projected to reduce water availability, intensifying water scarcity and vulnerability during dry months. A decline in water availability for human consumption, agriculture, and other uses is anticipated. | Sone et al. [9]; Vieira et al. [80]; Ballarin et al. [81]; Gesualdo et al. [82]; Thomaz et al. [83]; |

| Chile | Changes in land use and land cover are projected to reduce native and mixed forests, agricultural lands, and both young and mature non-native forest plantations. This will reduce soil water storage, diminish water availability, and decrease aquifer recharge due to lower percolation and groundwater flow. Consequently, water security within the region is expected to be negatively affected. | Pereira et al. [85] | |

| Colombia | Projected increases in rainfall variability and intensity exacerbate water security issues. Soil management practices and changes in vegetation cover influence water availability and quality. Agricultural practices are identified as primary contributors to sedimentation and nutrient pollution in groundwater. Also, the decline in forested areas increases surface runoff during peak rainfall periods affecting agricultural productivity and sediment transport. | Valencia et al. [86]; Ortegón et al. [87]; Ruíz et al. [88] | |

| Ecuador | Water availability is under threat due to climate change and land use changes driven by urbanization and agricultural activities. Future scenarios predict increased water deficits caused by rising temperatures, higher evaporation rates, and reduced precipitation. Growing water scarcity is expected, alongside increased agricultural demand, irrigation expansion, and higher energy requirements for water pumping and transport, particularly in the Machángara Basin. Additionally, anthropogenic activities, such as sedimentation and agricultural wastewater discharge, may lead to water eutrophication. | Chengot et al. [13]; Avilés et al. [54]; Ayala et al. [55] | |

| Peru | Current water availability exceeds demand in the Vilcanota-Urubamba, Ambato and Coata basin, and climate change scenarios predict a further increase in availability particularly during the dry season. Population growth and agricultural expansion are the primary drivers of rising demand. jeopardizing water supplies for both human and agricultural use. While some models forecast increased annual precipitation, reductions in critical-month flows intensify the challenge. Additionally, forest cover loss has diminished the basin’s capacity for hydrological regulation, heightening flood risks during the rainy season and reducing base flow during the dry season. | Goyburo et al. [47]; Salomón et al. [48]; Laveriano et al. [49]; Olsson et al. [50]; Paiva et al. [51] | |

| Australia | Australia | Changes in land use and land cover reduce infiltration and exacerbate surface runoff alternating flow patterns also combine with the increases in rainfall intensity. Also, periods of prolonged drought combined with increased water demands and overloading of nutrients from agricultural activities, urban wastewater discharge, soil erosion and sediment transport exacerbate water quality issues. | Das et al. [53] |

References

- Zhou, J.R.; Li, X.Q.; Yu, X.; Zhao, T.C.; Ruan, W.X. Exploring the ecological security evaluation of water resources in the Yangtze River Basin under the background of ecological sustainable development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; He, W.; Jiang, E.; Yuan, L.; Qu, B.; Degefu, D.M.; Ramsey, T.S. Evaluation and prediction of water security levels in Northwest China based on the DPSIR model. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkeba, F.T.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Brauman, K.A.; Kumar, M. Indicator metrics and temporal aggregations introduce ambiguities in water scarcity estimates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Meshesha, T.W.; Sen, I.S.; Bol, R.; Bogena, H.; Wang, J. Assessing impacts of land use and land cover [LULC] Change on stream flow and runoff in Rur Basin, Germany. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ou, D.; Li, Y. A study on spatial variation of water security risks for the Zhangjiakou Region. J. Resour. Ecol. 2021, 12, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, A.K.; Giupponi, C.; Wada, Y. Measuring global water security towards sustainable development goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 124015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Tavares, P.; Acosta, R.; Nobre, P.; Resende, N.C.; Chou, S.C.; de Arruda Lyra, A. Water balance components and climate extremes over Brazil under 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C of global warming scenarios. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhou, G.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Dai, A.; Wang, F.; Gentine, P.; Zhang, G.; Song, Y.; Zhou, D. Rising rainfall intensity induces spatially divergent hydrological changes within a large river basin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, J.S.; Araujo, T.F.; Gesualdo, G.C.; Ballarin, A.S.; Carvalho, G.A.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Wendland, E.C. Water security in an uncertain future: Contrasting realities from an availability-demand perspective. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, S.; Allen, D.M. Risk to water security for small islands: An assessment framework and application. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaykiran, S.; Cuceloglu, G.; Ekdal, A. Estimation of water budget components of the Sakarya River Basin by using the WEAP-PGM model. Water 2019, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Hao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, B.; He, X.; et al. Climate change and water security in the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengot, R.; Zylberman, R.; Momblanch, A.; Salazar, O.V.; Hess, T.; Knox, J.W.; Rey, D. Evaluating the impacts of agricultural development and climate change on the water-energy nexus in Santa Elena [Ecuador]. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 152, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, A.; Panagopulos, Y.; Konsta, D.; Mimikou, M. Designing water efficiency measures in a catchment in Greece using WEAP and SWAT models. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saka, F.; Mohammady, A.J. Future perspective of water budget in the event of three scenarios in Afghanistan using the WEAP program. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 49, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sediqi, M.N.; Komori, D. Assessing water resource sustainability in the Kabul River Basin: A standardized runoff index and reliability, resilience, and vulnerability framework approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, F.; Ondrasek, G.; Islam, M.S.; Maina, J.M.; Beaumont, L.J. Combined impacts of climate and land use changes on long-term streamflow in the Upper Halda Basin, Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Dai, C. Impacts of climate and land use/land cover change on water yield services in Heilongjiang Province. Water 2024, 16, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Shen, B.; Song, X.; Mo, S.; Huang, L.; Quan, Q. Multi-temporal variabilities of evapotranspiration rates and their associations with climate change and vegetation greening in the Gan River Basin, China. Water 2019, 11, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, S.; Chen, C.; Clark, D.B.; Folwell, S.; Gosling, S.N.; Haddeland, I.; Hanasaki, N.; Heinke, J.; Ludwig, F.; Voß, F.; et al. Climate change impact on available water resources obtained using multiple global climate and hydrology models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2012, 3, 1321–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.; Howard, G.; Nijhawan, A.; Poudel, M.; Geremew, A.; Mulugeta, Y.; Lo, E.; Ghimire, A.; Baidya, M.; Sharma, S. Managing climate change challenges to water security: Community water governance in Ethiopia and Nepal. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2024, 11, e00135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, F.; Awan, U.K.; Borgemeister, C.; Tischbein, B. Coupling remote sensing and hydrological model for evaluating the impacts of climate change on streamflow in data-scarce environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, M.; Mainuddin, M. The impact of climate change, population growth and development on sustainable water security in Bangladesh to 2100. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, I.; Jain, K. Simple methodology for estimating the groundwater recharge potential of rural ponds and lakes using remote sensing and GIS techniques: A spatiotemporal case study of Roorkee Tehsil, India. Water Resour. 2020, 47, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, D.; Kothandaraman, S.; Kuppusamy, M. Simulation of water balance components using SWAT model at sub catchment level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabale, R.S.; Bobade, S.S.; Venkatesh, B.; Jose, M.K. Application of Arc-SWAT model for water budgeting and water resource planning at the Yeralwadi Catchment of Khatav, India. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024, 23, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mishra, A.; Singh, U.K. Assessment of land cover changes and climate variability effects on catchment hydrology using a physically distributed model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhwani, K.; Eldho, T.I. Assessing the vulnerability of water balance to climate change at river basin scale in humid tropics: Implications for a sustainable water future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.K.; Kim, J.; Her, Y.; Sharma, D.; Jeong, H. Hydroclimatic impact assessment using the SWAT model in India—State of the art review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivesh, S.; Patil, J.P.; Goyal, V.C.; Saran, B.; Singh, A.K.; Raizada, A.; Malik, A.; Kuriqui, A. Assessment of future water demand and supply using WEAP model in Dhasan River Basin, Madhya Pradesh, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 27289–27302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, S.L.; Keesara, V.R.; Sridhar, V. Prediction of future lake water availability using SWAT and support vector regression (SVR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukika, K.N.; Keesara, V.R.; Buri, E.S.; Sridhar, V. Predicting the effects of land use land cover and climate change on Munneru River Basin using CA-Markov and soil and water assessment tool. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez-Mejía, P.; Tzatchkov, V.; Rodríguez-Varela, J.M.; Llaguno-Guilberto, O.J. Calidad del agua y seguridad ante inundaciones en la gestión sostenible del recurso hídrico. Ing. Agua 2021, 25, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, A.; Valdés-Rodríguez, O.A.; Villada-Canela, M.; Manson, R.; Murrieta-Galindo, R. Caracterizando la seguridad hídrica con enfoque de cuenca hidrológica: Caso de estudio Veracruz, México. Ing. Agua 2021, 25, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Cruz, J.A.; Fernández-Montes De Oca, A.; Rives, C. Detección de amenazas y oportunidades para la conservación en la cuenca baja del Usumacinta a partir de técnicas de percepción remota. Ecosistemas 2019, 28, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leija, E.G.; Valenzuela, S.I.; Valencia, M.; Jiménez, G.; Castañeda, G.; Reyes, H.; Mendoza, M.E. Análisis de cambio en la cobertura vegetal y uso del suelo en la región centro-norte de México. El caso de la cuenca baja del río Nazas. Ecosistemas 2020, 29, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colín-García, G.; Palacios-Vélez, E.; López-Pérez, A.; Bolaños-González, M.A.; Flores-Magdaleno, H.; Ascencio-Hernández, R.; Canales-Islas, E.I. Evaluation of the impact of climate change on the water balance of the Mixteco River Basin with the SWAT model. Hydrology 2024, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Sánchez, C.; Chávez-Morales, J.; Palacios-Vélez, L.O.; Ibáñez-Castillo, L.A. Simulación hidrológica de la cuenca del río Laja con el modelo WEAP. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2022, 13, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreika, N.; Winterová, J.; Li, T.; Krása, J.; Dostál, T. The small water cycle in the czech landscape: How has it been affected by land management changes over time? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Q.; Niu, Z.; Zhu, G.; Jin, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, H. A new socio-hydrology system based on system dynamics and a SWAT-MODFLOW coupling model for solving water resource management in Nanchang City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y. Spatial–temporal variation analysis of water storage and its impacts on ecology and environment in high-intensity coal mining areas. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhu, Y.; Lou, W.; Xie, B.; Sheng, L.; Hu, H.; Zheng, K.; Gu, Q. Temporal stability analysis for the evaluation of spatial and temporal patterns of surface water quality. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Cao, Y.; Wu, M.; Song, M.; Wang, L. A novel method for watershed best management practices spatial optimal layout under uncertainty. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, R.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Xue, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, L. Temporal and spatial variation trends in water quality based on the WPI index in the shallow lake of an arid area: A case study of Lake Ulansuhai, China. Water 2019, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Towards the sustainable development of water security: A new copula-based risk assessment system. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.S.; Gill, L.W.; Pilla, F.; Basu, B. Assessment of variations in runoff due to landcover changes using the SWAT model in an Urban River in Dublin, Ireland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyburo, A.; Rau, P.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Buytaert, W.; Cuadros-Adriazola, J.; Horna, D. Assessment of present and future water security under anthropogenic and climate changes using WEAP model in the Vilcanota-Urubamba Catchment, Cusco, Perú. Water 2023, 15, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomón, M.; Guaman Ríos, C.; Rubio, C.; Galárraga, R.; Abraham, E. Indicadores de uso del agua en una zona de los Andes centrales de Ecuador. Estudio de la cuenca del Río Ambato. Ecosistemas 2008, 17, 72–85. Available online: https://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/114 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Laveriano, E.B.; Huamaní, J.R.; Rosas, M.A. Optimization of water resources to counteract the effects of water deficit using the WEAP Model. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering, Chestmut Conference Centre-University of Torronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–15 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.; Kämäräinen, M.; Santos, D.; Seitola, T.; Tuomenvirta, H.; Haavisto, R.; Lavado-Casimiro, W. Downscaling climate projections for the Peruvian coastal Chancay-Huaral Basin to support river discharge modeling with WEAP. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 13, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, K.; Rau, P.; Montesinos, C.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Bourrel, L.; Frappart, F. Hydrological response assessment of land cover change in a Peruvian Amazonian Basin impacted by deforestation using the SWAT Model. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L.T.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M. Determination of spatially-distributed hydrological ecosystem services (HESS) in the Red River Delta using a calibrated SWAT model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ahsan, A.; Khan, M.H.R.B.; Yilmaz, A.G.; Ahmed, S.; Imteaz, M.A.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Shafiqzzaman, M.; Ng, A.W.M.; Al-Ansari, N. Calibration, validation and uncertainty analysis of a SWAT water quality model. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilés, A.; Palacios, K.; Pacheco, J.; Jiménez, S.; Zhiña, D.; Delgado, O. Sensitivity exploration of water balance in scenarios of future changes: A case study in an Andean regulated river basin. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 141, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Izurieta, J.E.; Beltrán Dávalos, A.A.; Jara Santillán, C.A.; Godoy Ponce, S.C.; Van Wittenberghe, S.; Verrelst, J.; Delegido, J. Spatial and temporal analysis of water quality in High Andean Lakes with Sentinel-2 satellite automatic water products. Sensors 2023, 23, 8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera Abdi, D.; Ayenew, T. Evaluation of the WEAP model in simulating subbasin hydrology in the Central Rift Valley basin, Ethiopia. Ecol. Process 2021, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidanewold, B.B.; Zeleke, E.B.; Michailovsky, C.I.; Seyoum, S. Partitioning blue and green water sources of evapotranspiration using the water evaluation and planning (WEAP) model. Water Pract. Technol. 2023, 18, 2943–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedefaw, M.; Denghua, Y. Simulation of stream flows and climate trend detections using WEAP model in awash river basin. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2211365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, B.Z.; Assefa, T.T.; Tigabu, T.B.; Abebe, W.B.; He, L. Hydrological modeling of the Kobo-Golina River in the data-scarce Upper Danakil Basin, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, S.; Ben Salem, A.; Karmaoui, A.; Yacoubi, M. Vulnerability of water resources to drought risk in southeastern Morocco: Case study of Ziz Basin. Water 2023, 15, 4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevárez-Favela, M.M.; Fernández-Reynoso, D.S.; Sánchez-Cohen, I.; Sánchez-Galindo, M.; Macedo-Cruz, A.; Palacios-Espinosa, C. Comparación de los modelos WEAP y SWAT en una cuenca de Oaxaca. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2021, 12, 358–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Servín, A.G.; Guerrero-García, H.R.; Colín-Martínez, R. Análisis econométrico de la disponibilidad de agua para producción agrícola de riego en México (2003–2015). Ecosistemas 2020, 29, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitane, A.; Essahlaoui, A.; Van Griensven, A.; Yimer, E.A.; Essahlaoui, N.; Mohajane, M.; Chawanda, C.J.; Van Rompaey, A. Towards a decision-making approach of sustainable water resources management based on hydrological modeling: A case study in Central Morocco. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlati, M.L.; Antohi, V.M.; Ionescu, R.V.; Iticescu, C.; Georgescu, L.P. Quantyfing the impact of the water security index on socio-economic development in EU27. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 93, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, M.; Tomczyk, P.; Wiatkowski, M. Water management on drinking water reservoirs in the aspect of climate variability: A case study of the Dobromierz Dam Reservoir, Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Gunn, E.; Vargas Amelin, E. La gobernanza del agua subterránea y la seguridad hídrica en España. In Book El agua en España: Economía y gobernanza; Secretaría de Estado de Presupuestos y Gastos: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 79–102. Available online: https://www.ief.es/docs/destacados/publicaciones/revistas/pgp/101.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Núñez, M.; Pfister, S.; Antón, A.; Muñoz, P.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Rieradevall, J. Assessing the environmental impact of water consumption by energy crops grown in Spain. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, X.; Estrada, L.; Llorente, O.; Acuña, V. Assessing small hydropower viability in water-scarce regions: Environmental flow and climate change impacts using a SWAT+ based tool. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eekhout, J.P.C.; Delsman, I.; Baartman, J.E.M.; van Eupen, M.; van Haren, C.; Contreras, S.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; de Vente, J. How future changes in irrigation water supply and demand affect water security in a Mediterranean catchment. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 297, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.F.; Chen, D.; Wang, B.; Ou, T.; Lu, M. Human-induced warming accelerates local evapotranspiration and precipitation recycling over the Tibetan Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital, U.; Dwivedi, D.; Brown, J.B.; Steefel, C.I. Downscaled hyper-resolution (400 m) gridded datasets of daily precipitation and temperature (2008–2019) for the East–Taylor subbasin (western United States). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4949–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostedt, E.C.E.S. Quantifying Water Security in West Virginia and the Potomac River Basin. Master’s Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2022. Available online: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11389&context=etd (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ridgway, P.; Lane, B.; Canham, H.; Murphy, B.P.; Belmont, P.; Rengers, F.K. Wildfire, extreme precipitation and debris flows, oh my! Channel response to compounding disturbances in a mountain stream in the Upper Colorado Basin, USA. Earth Surf. Process Landf. 2024, 49, 3855–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompas, T.; Che, T.N.; Grafton, R.Q. Global impacts of heat and water stress on food production and severe food insecurity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tena, T.M.; Mwaanga, P.; Nguvulu, A. Hydrological modelling and water resources assessment of Chongwe River Catchment using WEAP model. Water 2019, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, K.A.; Alshihabi, O. Assessment of future Syrian water resources supply and demand by the WEAP model. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari Mejdar, H.; Moridi, A.; Najjar-Ghabel, S. Water quantity–quality assessment in the transboundary river basin under climate change: A case study. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 4747–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessedik, M.; Abdelbaki, C.; Tiar, S.M.; Badraoui, A.; Megnounif, A.; Goosen, M.; Mourad, K.; Baig, M.B.; Alataway, A. Strategic decision-making in sustainable water management using demand analysis and the water evaluation and planning model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjebieur, E.; Ghrieb, L.; Maoui, A.; Chaffai, H.; Chini, Z.L. Long-term water demand assessment using WEAP 21: Case of The Guelma Region, Middle Seybouse (Northeast Algeria). Geogr. Tech. 2021, 16, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.F.B.; Rolim, F.C.; Carvalho, M.N.; Caldas, A.M.; Costa, R.C.A.; Silva, K.S.d.; Parahyba, R.d.B.V.; Pacheco, F.A.L.; Fernandes, L.F.S.; Pissarra, T.C.T. Water security assessment of groundwater quality in an anthropized rural area from the Atlantic forest biome in Brazil. Water 2020, 12, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, A.S.; Sousa Mota Uchôa, J.G.; dos Santos, M.S.; Almagro, A.; Miranda, I.P.; da Silva, P.G.C.; da Silva, G.J.; Gomes Júnior, M.N.; Wendland, E.; Oliveira, P.T.S. Brazilian water security threatened by climate change and human behavior. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2023WR034914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, G.C.; Oliveira, P.T.; Rodrigues, D.B.B.; Gupta, H.V. Assessing water security in the São Paulo metropolitan region under projected climate change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4955–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, F.R.; Miguez, M.G.; De Souza, J.G.; De Moura, G.W.; Fontes, J.P. Water scarcity risk index: A tool for strategic drought risk management. Water 2023, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Azam, S.; Sauchyn, D.; Basu, S. Assessment of meteorological and agricultural drought indices under climate change scenarios in the South Saskatchewan River Basin, Canada. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.O.; Escanilla-Minchel, R.; González, A.C.; Alcayaga, H.; Aguayo, M.; Arias, M.A.; Flores, A.N. Assessment of future land use/land cover scenarios on the hydrology of a coastal basin in South-Central Chile. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.; Villegas, J.C.; Hoyos, N.; Duque-Villegas, M.; Salazar, J.F. Streamflow response to land use/land cover change in the tropical Andes using multiple SWAT model variants. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 54, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortegón, Y.A.C.; Acosta-Prado, J.C.; Acosta Castellanos, P.M. Impact of land cover changes on the availability of water resources in the Regional Natural Park Serranía de Las Quinchas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz-Ordoñez, D.M.; Camacho De Angulo, Y.V.; Pencué Fierro, E.L.; Figueroa Casas, A. Mapping ecosystem services in an Andean Water Supply Basin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla, J.H.; Osorio, M.D.; Gonzalez, F.; Pérez, J.D. Grain sorghum (Sorgum vulgare L. Monech) response to irrigation time and nitrogen fertilizer during two plantation dates. In Book. Revista Ingeniería Agrícola; Instituto de Investigaciones de Ingeniería Agrícola: La. Habana, Cuba, 2016; Volume 6, pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amisigo, B.A.; McCluskey, A.; Swanson, R. Modeling impact of climate change on water resources and agriculture demand in the Volta Basin and other basin systems in Ghana. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6957–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abungba, J.A.; Adjei, K.A.; Gyamfi, C.; Odai, S.N.; Pingale, S.M.; Khare, D. Implications of land use/land cover changes and climate change on Black Volta Basin future water resources in Ghana. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaabani, M.K.; Abedi-Koupai, J.; Eslamian, S.S.; Gohari, S.A.R. Simulation of the effects of climate change, crop pattern change, and developing irrigation systems on the groundwater resources by SWAT, WEAP and MODFLOW models: A case study of Fars province, Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 10485–10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najimi, F.; Aminnejad, B.; Nourani, V. Assessment of climate change’s impact on flow quantity of the mountainous watershed of the Jajrood River in Iran using hydroclimatic models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.H.; Ashofteh, P.S.; Loáiciga, H.A. Optimal water allocation of surface and ground water resources under climate change with WEAP and IWOA modeling. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 3181–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikha-BagemGhaleh, S.; Babazadeh, H.; Rezaie, H.; Sarai-Tabrizi, M. The effect of climate change on surface and groundwater resources using WEAP-MODFLOW models. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Adib, A.; Bajestan, M.S.; Beigipoor, G.H. Non-priority and priority allocation policies in water resources management concerning water resources scarcity using the WEAP model in the catchment area of Fars province. J. Hydraul. Struct. 2022, 8, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, H.; Javadi, S.; Eini, M.R.; Golmohammadi, G. Compilation simulation of surface water and groundwater resources using the SWAT-MODFLOW model for a karstic basin in Iran. Hydrogeol. J. 2023, 31, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, A.A.; Abdulhameed, I.M.; Mawlood, I.A. Application of WEAP model for managing water resources in Iraq: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1222, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Al-Khafaji, M.S.; Al-Faraj, F.A.M.; Uzomah, V. Sustainable adaptation plan in response to climate change and population growth in the Iraqi part of Tigris River Basin. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.B.A.; Abdulhameed, I.M.; Sulaiman, S.O. Improving the cultivated area for the Ramadi Irrigation Project By Using Water Evaluation and Planning Model. Iraqi Acad. Sci. J. 2021, 26, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhameed, I.M.; Sulaiman, S.O.; Najm, A.B.A.; Al-Ansari, N. Optimising water resources management by using water evaluation and planning (WEAP) in the West of Iraq. J. Water Land Dev. 2022, 53, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, A.; Becker, R.; Adeniyi, O.D.; Pilla, G.; Sadeghi, S.H.; Maerker, M. Hydrological implications of recent droughts (2004–2022): A SWAT-based study in an ancient lowland irrigation area in Lombardy, Northern Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zy Harifidy, R.; Zy Misa Harivelo, R.; Hiroshi, I.; Jun, M.; Kazuyoshi, S. A systematic review of water resources assessment at a large river basin scale: Case of the major river basins in Madagascar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, M.; Phuyal, S.; Mahato, R.; Shrestha, A.; Pudasaini, U.; Lama, S.D.; Chapagain, A.R.; Mehan, S.; Neupane, D. Assessing climate change impacts on streamflow and baseflow in the Karnali River Basin, Nepal: A CMIP6 multi-model ensemble approach using SWAT and web-based hydrograph analysis tool. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Khalid, S.; Rasheed, H. Social implications of water scarcity in local community of district Rawalpindi. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Arch. IJSSA 2024, 7, 412–415. Available online: https://www.ijssa.com/index.php/ijssa (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Amin, A.; Iqbal, J.; Asghar, A.; Ribbe, L. Analysis of current and future water demands in the upper indus basin under IPCC climate and socio-economic scenarios using a hydro-economic WEAP model. Water 2018, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Saleem, M.W.; Rashid, M.; Ditthakit, P.; Weesakul, U.; Kaewmoracharoen, M. Integration of the water evaluation and planning system model with the Nash bargaining theory for future water demand and allocation in the Kabul River Transboundary basin under different scenarios. Eng. Sci. 2024, 30, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabari, S.; Shahrour, I.; El Khattabi, J. Assessment of the urban water security in a severe water stress area–application to Palestinian cities. Water 2020, 12, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabari, S.; Shahrour, I.; Khatabi, J. Use of risk analysis for water security assessment. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 295, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, J. A Study: Water security and climate change risks for municipalities. IMIESA 2022, 47, 5–14. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-imiesa_v47_n5_a14 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Nagan, V.; Seyam, M.; Abunama, T. Assessment of long-term water demand for the Mgeni system using Water Evaluation and Planning [WEAP] model considering demographics and extended dry climate periods. Water SA 2023, 49, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, N.; Senzanje, A.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing climate change impacts on surface water availability using the WEAP model: A case study of the Buffalo river catchment, South Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 46, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, H.H.; Chang, S.W.; Lee, J.E.; Chung, I.M. Assessment of hydrological responses to land use and land cover changes in forest-dominated watershed using SWAT model. Water 2024, 16, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Sung, J.H.; Chung, E.S.; Kim, S.U.; Son, M.; Shiru, M.S. Comparison of projection in meteorological and hydrological droughts in the Cheongmicheon Watershed for RCP4.5 and SSP2-4.5. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, M.; Min, J.H.; Na, E.H. Integrated assessment of the land use change and climate change impact on baseflow by using hydrologic model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishiwa, P.; Nobert, J.; Kongo, V.; Ndomba, P. Assessment of impacts of climate change on surface water availability using coupled SWAT and WEAP models: Case of upper Pangani River Basin, Tanzania. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2018, 378, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş Özgenç, E. Evaluation using the SWAT model of the effects of land use land cover changes on hydrological processes in the Gala Lake Basin, Turkey. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 34, e22238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylan, E.D. An Approach for future droughts in Northwest Türkiye: SPI and LSTM methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Xuan, Y.; Bailey, R.T. Assessing climate change impact on water resources in water demand scenarios using SWAT-MODFLOW-WEAP. Hydrology 2022, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Habimana, J.d.D.; Kim, S.-H.; Bae, D.-H. Assessment of climate change impacts on the hydroclimatic response in Burundi Based on CMIP6 ESMs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, G. Study on the mechanism of multi-scalar transboundary water security governance in the Shenzhen River. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriagasa, M.C.; Tongdeenok, P.; Kaewjampa, N. Assessing the implication of climate change to forecast future flood using SWAT and HEC-RAS model under CMIP5 climate projection in Upper Nan Watershed, Thailand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhou, X.; Gu, A. Effects of climate change on hydropower generation in China based on a WEAP model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganoulis, J. A New Dialectical model of water security under climate change. Water 2023, 15, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lu, H.; Wang, B. Benefit distribution mechanism of a cooperative alliance for basin water resources from the perspective of cooperative game theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Bollmann, H.A.; Pasqual Lofhagen, J.C.; Bravo-Montero, L.; Carrión-Mero, P. Approach on water-energy-food (WEF) nexus and climate change: A tool in decision-making processes. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Mu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Yang, R. Ecological water requirement of natural vegetation in the Tarim River Basin based on multi-source data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Jiang, N.; Jin, C.; Nie, T.; Gao, Y.; Meng, F. Analysis of spatial and temporal variation in sustainable water resources and their use based on improved combination weights. Water 2023, 15, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y. Land use intensity alters ecosystem service supply and demand as well as their interaction: A spatial zoning perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R. Determination of river ecological flow thresholds and development of early warning programs based on coupled multiple hydrological methods. Water 2024, 16, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heumer, F.; Grischek, T.; Tränckner, J. Water supply security—Risk management instruments in water supply companies. Water 2024, 16, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza Sanz, D.; Vizcaino Martínez, P. Estimación de caudales ecológicos en dos cuencas de Andalucía: Uso conjunto de aguas superficiales y subterráneas. Ecosistemas 2008, 17, 24–36. Available online: https://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/112 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Campos, J.A.; Da Silva, D.D.; Pires, G.F.; Filho, E.I.F.; Amorim, R.S.S.; de Menezes, F.C.M.; de Melo, C.B.; Lorentz, J.F.; Aires, U.R.V. Modeling environmental vulnerability for 2050 considering different scenarios in the Doce River Basin, Brazil. Water 2024, 16, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principle Measures | Description | Water Security Issues Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable urban planning | Participatory planning based on human needs, environmental impacts, and governmental visions, including the coordinated use of surface and groundwater. | flash floods water scarcity and quality |

| Improving consumption efficiency | Water management based on supply: allocation and use of water in key sectors, adapting to the specific needs of each productive sector and implementing efficiency improvements in consumption. | water scarcity |

| Strategic land-use planning | Water resource planning based on the specific characteristics of each sub-basin (soil type, coverage, and agricultural practices), ensuring a balanced use of resources. | water scarcity; quality |

| Applying technologies to predict availability | The integration of technologies such as remote monitoring, geographic information systems (GIS), and predictive models in water management and planning. | water scarcity |

| Planning based on temporal resource variations | Plan the use and distribution of water resources according to the spatiotemporal patterns of precipitation changes and hydrological responses. | water scarcity |

| Developing disaster resilience infrastructure | Water retention infrastructure to address disasters such as floods, reducing the impact on communities and water resources. | flash floods |

| Creating storage facilities | Planning and construction of water storage facilities, such as reservoirs and dams, to promote aquifer recharge and increase water availability during dry periods. | water scarcity |

| Improving groundwater use | Combine use of Surface runoff and groundwater to maintain ecological flows in river sections that would otherwise be overexploited. | water scarcity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amparo-Salcedo, M.; Pérez-Gimeno, A.; Navarro-Pedreño, J. Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries. Water 2025, 17, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050633

Amparo-Salcedo M, Pérez-Gimeno A, Navarro-Pedreño J. Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries. Water. 2025; 17(5):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050633

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmparo-Salcedo, Maridelly, Ana Pérez-Gimeno, and Jose Navarro-Pedreño. 2025. "Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries" Water 17, no. 5: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050633

APA StyleAmparo-Salcedo, M., Pérez-Gimeno, A., & Navarro-Pedreño, J. (2025). Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries. Water, 17(5), 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050633