Form-Based Regulations to Prevent the Loss of Urbanity of Historic Small Towns: Replicability of the Monte Carasso Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Small Towns—Context

1.2. Questions and Goals

- The spatial effects achieved in Monte Carasso can be considered better (more consistent with the place character) than in the neighboring towns;

- The planning procedure and environment of Monte Carasso are replicable, so it is possible to create an abstract model of them, adaptable to local conditions.

1.3. Content

2. Methods

- Building density within the urbanized area (as a relation of the total built-up area in the entire urbanized area);

- Population density (as a ratio of population to the urbanized area);

- The compactness of the town (number of buildings in a zone within a five-minute walk to the central point in relation to the total number of buildings; the focal point was designated in two variants: as the town hall and the geometric center of the urbanized area—“centroid”);

- The scale of buildings (number of buildings with a built-up area exceeding 2000 m2/500 m2).

3. The Monte Carasso Case—Components of Urban Transformation

3.1. Context

3.1.1. Geographical and Historical Location

3.1.2. Luigi Snozzi in Monte Carasso

- High building density;

- Strong and hierarchical structure;

- Clearly delineated city limits;

- Clear separation between private and public space (symbolic, as well as physical and visual);

- Presence of a monumental and symbolic public space;

- Secondary, “subordinated” role of natural elements within the urban fabric [42].

3.2. Elements of the Planning Environment of Monte Carasso

3.2.1. Spatial Planning in Ticino

3.2.2. Urban Code

- Buildings can be built if:

- ⚬

- (…) the land is urbanized. The land is urbanized if there is sufficient access to it and the necessary water, energy, and sewage networks are close enough to be able to conclude a contract without easement;

- ⚬

- The plot must be used rationally and in moderation;

- ⚬

- Interventions on the plot (…) must be carried out taking into account, and respecting, the nature of the plot and the existing urban and architectural structure;

- ⚬

- There must be a reasonable relationship between the built-up and undeveloped areas;

- ⚬

- Only surfaces necessary for the use of the property in accordance with its intended use may be paved.

- Regarding the distance of buildings from the plot boundaries,

- ⚬

- New buildings may be situated:

- ▪

- Without windows—on the border with the neighboring plot;

- ▪

- With windows—2 m from the border.

- ⚬

- From the side of existing buildings, the following distances should be kept:

- ▪

- If there are doors, windows, and other viewing openings in the wall of the neighboring building, 4 m;

- ▪

- If there are windows and other openings that only provide light (not viewing), or if there are no openings, 3 m.

- ⚬

- Owners can agree to reduce the indicated distances (…);

- ⚬

- The distance of new buildings from streets, squares in urbanized zones (…) can be built directly on plot edge.

- In terms of building height,

- ⚬

- (…) Maximum height of new buildings up to 9 m; in addition, an additional 1.5 m may be allocated.

- Regarding fences,

- ⚬

- From the side of streets and squares, the plots must be fenced with a wall of a minimum height of 0.8 m. (…);

- ⚬

- The maximum height of the walls is 2.5 m (…).

- As regards parceling recomposition,

- ⚬

- Within building zones, where the layout of plots does not allow for their rational use, an order to modify the ownership system is introduced.

- Regarding expert commission,

- ⚬

- The city office appoints a commission of three experts to:

- ▪

- Provide advice to private owners on the proper use of plots of land for building purposes;

- ▪

- Check all public and private projects.

3.2.3. Expert Commission

3.3. Auxiliary Activities

3.3.1. Design of Key Urban Elements

3.3.2. Design Examples of the Ordinary Urban Fabric

- Individual shelter—usually house for a single family;

- Urban context, urban fabric—framing, creating walls and boundaries of public space;

- Spatial cases, legal precedent—examining the rules of the code;

- Informative example—educating investors and architects, whereby helping to overcome the patterns of thought that separate the idea of a private residence and the idea of a town.

3.3.3. Design Seminar

4. Spatial Characteristics

4.1. Parameters

4.2. Descriptive Assessment

- A visible border, i.e., a separation of the urban structure from its surroundings, which is a characteristic shared also by Sementina, although there is a visible pressure to develop lower parts of the hills to the north of both settlements;

- An irregular form of public spaces resulting from the organic development of the urban fabric;

- The legible enclosure of public spaces perceived as interiors with annexes;

- A clear definition of spatial privacy through physical separation of a building or a wall;

- Close viewing perspectives provide the ability to perceive details from close distances;

- Spontaneous mobility, without segregating the various modes of transport;

- Exclusive use of large-scale building types for public-use buildings;

- Height of buildings of usually one or two stories, occasionally three;

- “Personalization” of spatial issues, i.e., visibility of individual activity on the scale of the entire town.

5. Discussion

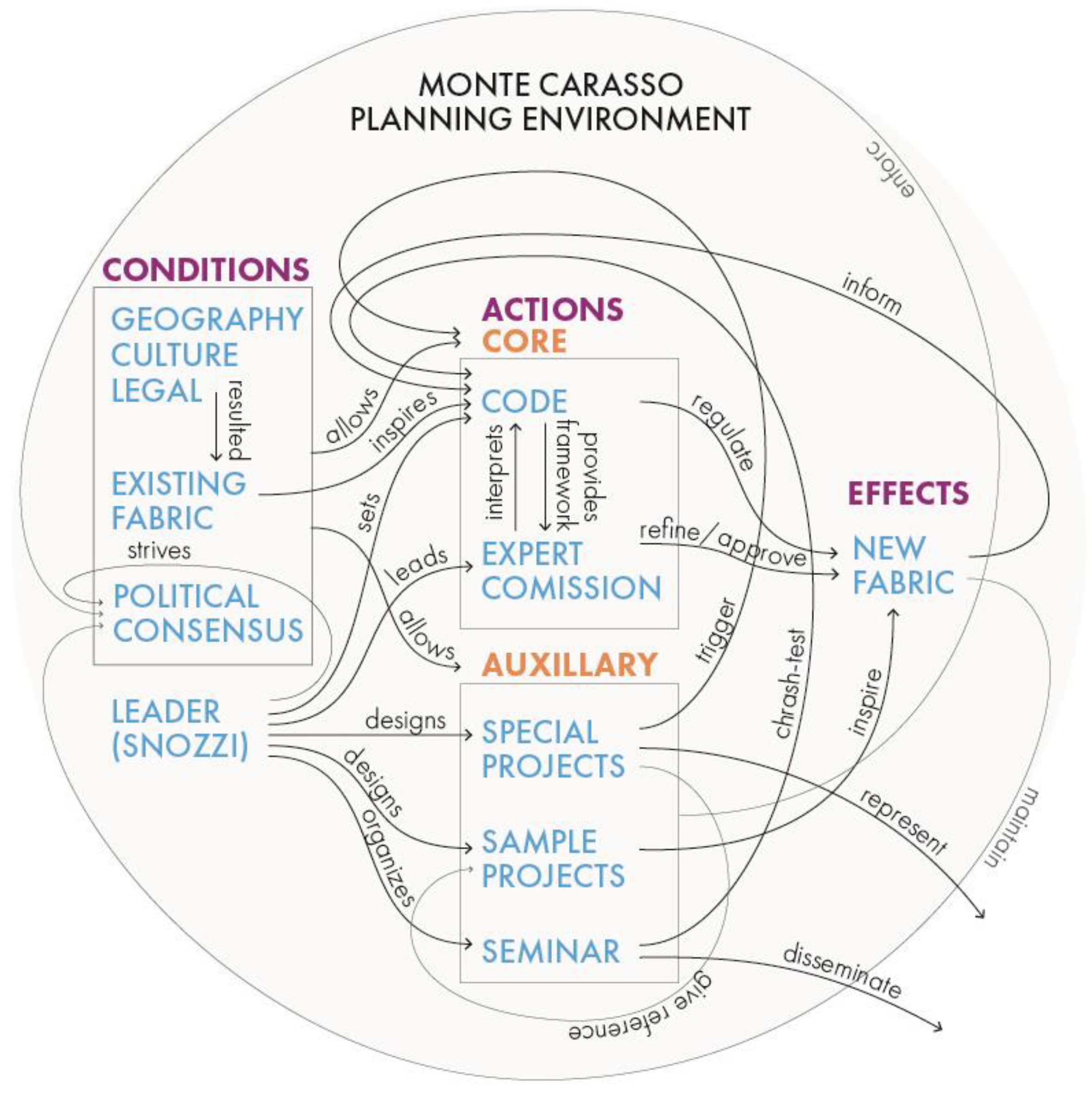

5.1. Mechanics of the Monte Carasso Planning Environment

- Geographic and cultural conditions: As Snozzi himself claimed, followed by scholars [41,57], the civic culture of Switzerland, immersed in geographic context, played an important role in the implementation of the revolutionary planning procedure. Its most relevant elements included trust in institutions, respect for the law, good organization, and individual modesty. Climatic conditions, which could be considered as an important factor influencing the morphology (determined distances and parameters), had some significance, but they could hardly be proven as decisive for the success of the project. This is because similar traditional compact centers can be found in various geographical locations. The overall influence of these contexts is generally hard to assess objectively. They can be considered favorable but not determinant.

- Legal conditions: In particular, the substantial autonomy of local (cantonal, municipal) governments in the Swiss Confederation enabled the use of the described procedure. While the local municipal mandate to control its territory by the planning process is generally a standard in most countries, the differentiation of construction law is much less frequent. This internal differentiation includes basic “technical” norms such as building distances and their relation with the public space. This element seems crucial in the procedure under consideration, as it could not be carried out without the possibility of overriding central building laws and regulations. The morphological provisions of the building code in Monte Carasso concern issues traditionally considered as “planning” (and most often under the authority of local government) such as land-use functions and parameters, but also (and mostly) include building regulations, which are usually regulated at the national level.

- Existing urban fabric: With its legible morphological features, the historical tissue was a direct inspiration for the formulation of rules within urban code. The most important spatial characteristics, such as building typology and its dimensions, the close proximity of buildings, direct access to the buildings from the street, presence of high opaque walls were abstracted and parameterized within the provisions of the local law. The latter, despite the fact that it contains universal features for many historical towns, also has particular features that are typical for this alpine location (e.g., fencing walls). It is, therefore, a certain synthesis of the local building tradition.

- Political consensus: This element was specified as a separate factor in the diagram despite its partial randomness and dependence on the cultural and legal context described above. The urban transformation of Monte Carasso could only have happened with the full support of local authorities. The relationship between an architect (Snozzi) and a politician (Guidotti) is often considered exemplary in this case. It was characterized by the absolute trust in each other’s competence, which made possible and even caused several controversial features of the process: the absence of fair competition among local professionals, top-down approach, and scarcity of local consultations/community engagement practices. It needs to be noted that the political consensus factor is dynamic, i.e., it changes over time. A minimum amount of political consensus is required to start the process, but it is being strengthened with establishing procedures and with its first positive effects. Despite the good results, however, the political consensus is prone to external interference and needs to be taken care of.

- Leader: The role of Luigi Snozzi in the described urban transformation was absolutely central, especially in the first phase. This role consisted of conceiving the whole mechanism as well as developing and organizing it, monitoring and assessing its effects, as well as participating in it as a designer, tutor, and member of an expert commission. On the other hand, the exposed position of an architect may raise some doubts. It can even be seen as authoritarian. However, when assessing its importance, one must take into account that we are not dealing with a typical urban policy but with a pioneering experiment that required high discipline. Indeed the role of Luigi Snozzi was mitigated with time, as the procedure established itself. Partly embedded in this factor is the architect–politician relationship, which is described above. The possibility of such a relationship, however, was the result of the unique approach and moral attitude of Luigi Snozzi.

- Urban code and expert commission: These are key elements and the heart of the entire mechanism. Their main importance lies in their departure from the practice of detailed building regulations toward a model in which general town planning provisions are accompanied by the ad hoc opinions of experts. The relations between objective and subjective criteria are interesting—the code includes both rules with specific parameters (“three floors”, “two meters”, etc.) as well as expressions such as “correct proportions’’ and “character of place”. Such a construction allows the enrichment of the planning process with the concepts that are difficult to parameterize, such as harmony or spatial order. In addition, it is somewhat reminiscent of the historical, vernacular way of creating towns, where the regulations mainly concerned dimensions and distances, while the typology, form, and detail resulted from tradition (well-established collective construction knowledge).

- Special projects: Carrying out large projects had a double role. Firstly, it allowed the most important spatial problems of the city to be addressed in a precise and coordinated way. With the help of the larger resources involved, the key places in the town were developed, in both its center and outskirts. Secondly, these projects had a symbolic meaning, i.e., they allowed for a “new opening” and gave impetus to the planned reform. For this reason, they were crucial to the widespread acceptance and success of the project. In addition, the positive architectural effect of the special projects encouraged individual investors to commission their house designs to Luigi Snozzi.

- Sample projects: It seems that the exemplary implementation of a number of ordinary” projects to visualize the functioning of the new urban code was equally important. Designs of regular urban fabric have proven that it is possible to move away from the typical suburban pattern of single-family housing and that the traditional town form is not outdated. This example allowed the community to accept the new regulations. However, the mere commissioning of Snozzi’s projects was not obvious, and it seems that it was only possible due to the earlier success of his architectural intervention in the center of the town.

- Design Seminar: The role of the seminar for the very process of Monte Carasso’s transformation seems to be secondary. It facilitated the testing of a number of solutions, but they would have probably been implemented without it. It was of greater importance for the popularization of the Monte Carasso case outside its geographical context.

- A new urban fabric: The existence of a certain amount of new (based on the urban code) urban fabric at a specific point in time was critically important. It gave confidence in the new law and allowed the entire construction initiative to be shifted onto new tracks. This created a situation in which investments based on new rules became normal and natural in their context, as opposed to the (previously obvious) suburban types of buildings.

- Outcomes: Recognition and appreciation of the Monte Carasso case beyond its original geographical context were important for its internal acceptance. Even if not immediately understood, controversial urban processes were more easily accepted by residents when they were awarded or presented at prestigious exhibitions.

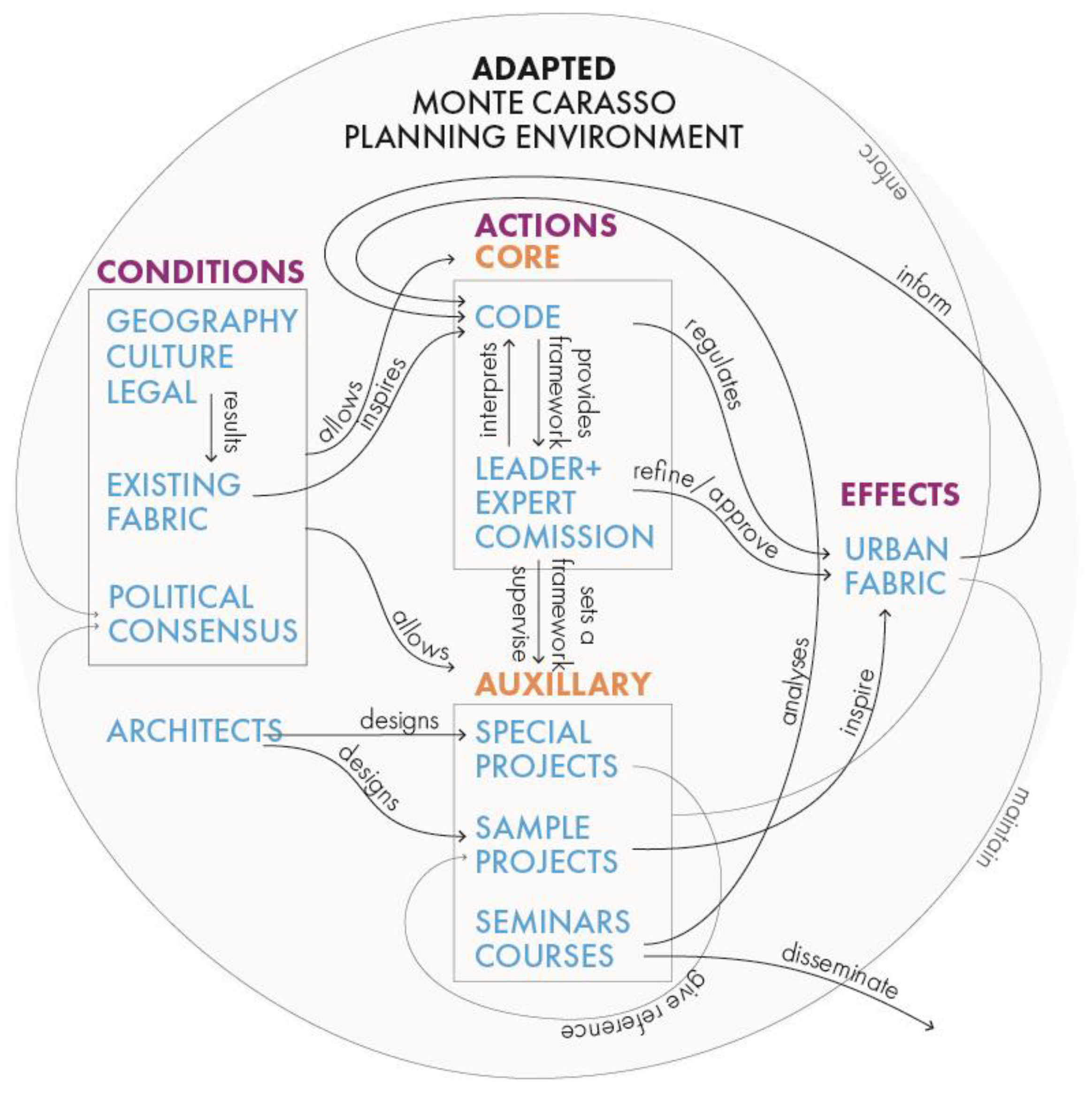

5.2. Potential of Adaptation

- Geographic and cultural conditions: As stated, a similar morphological character could be found in most small-town centers in Europe. Therefore, if historically it was possible to produce compact urban organisms in various geographical conditions, it should also be possible today. Some details, such as the numerical values of parameters or rules regarding the opacity of walls would probably be different depending on the climate and culture, but they would not undermine the essence of the system. The next factor, civic culture, may be of greater importance, as it determines the way of perceiving the top-down regulations. Depending on the tradition of a given country, it would require adapting the methods and schedule of introducing new regulations for each of the target contexts separately.

- Legal conditions: Certain legal autonomy of the local administrative entity is a condition for the application in an individual planning procedure. The mere introduction of unique urban codes for the area of a single town would have to be associated with granting it considerable legislative independence. It seems that it would be easier at the planning level than at the system level. This means that, under the local law, it would be possible to override general building regulations (e.g., exemption, derogation from the need to maintain minimum fire distances). An alternative would be to introduce top-down special technical regulations for the entire settlement category of small towns. Such regulations would take into account the fragmented and compact spatial character of towns (as opposed to large cities or dispersed rural areas). A more complex issue is the possibility of appointing and conferring competences on an expert commission. This moves beyond the planning sphere (even broadly understood along with technical and construction regulations) and concerns the form of the self-government system itself. In summary, it seems that granting considerable decision-making independence to local governments would be the optimal way.

- Existing urban fabric: Examined and analyzed and then synthesized and parameterized, this should be the basis for formulating the principles of local urban law. Such a process should begin with historical research identifying the characteristic features and evolution of the local building culture over time. It would be a morphological study because it concerns the built-up fabric itself, as well as invisible elements, in particular the system of public spaces and the property structure (parcellation). Only in relation to the latter should the three-dimensional form of the city be analyzed—starting from typological issues, through architectural issues (forms and details), and ending with the construction patterns (techniques and materials). Such an analysis necessarily includes some elements of valorization, as not all urban facts are equally relevant (in the context of establishing or revealing patterns).

- 4.

- Political consensus: The introduction of innovative planning regulations that would change the rules of local investment must be fully supported by the local authority. In that sense, it must, in part, be a political project, requiring initial trust and possibly an endorsement of the central government. Political consensus may be considered as the main challenge when a non-standard regulatory solution is introduced [26]. However, with a relatively smaller “decision structure”, small towns may overcome this problem more easily, because fewer people need to be convinced initially. When this occurs, effects could be achieved in a perspective longer than a single term of local government. Ensuring the continuity of the process would be the task of an independent body, a substantive multipartisan commission that would have the capacity to build support around the project, regardless of the ruling option. The feasible mode of functioning of such a commission is one of the main challenges of adapting the described system.

- 5.

- Leader/expert commission/architects: The process of spatial redevelopment of towns needs a guide, especially in the initial phase. In the case of Monte Carasso, the leader was, in a way, self-proclaimed, but in order to replicate such a procedure, his systemic role should be provided. This means that he must be appointed to a specific formal and legal position with substantial power granted. In different European contexts, various positions are devised, such as chief urban architect, urban planner, chairman of the town planning, and architectural commission. It depends on the legal and political structure considered earlier. As in the Monte Carasso case, the leader should be the head of the expert commission. In fact, his/her duties could be distributed among members of the commission. The challenge is to find professionals with sufficient experience, competence, and attitude to sit in the expert commission. An issue worth discussing is the possible sharing of such a body with a group of neighboring towns.

- 6.

- Urban code and expert commission: The two are designed to work together in order to take full advantage of their complementary nature. It seems that in the context of repeating this method elsewhere, it is absolutely necessary to stick to this combination with its fragile balance. The provisions cannot be too rigid so as to not marginalize the role of the committee and reduce it to the role of an “ornament”. They cannot be too open either, as this would give the committee too much power and risk abuse. Considerable caution is required when formulating specific provisions. It seems that the Monte Carasso set of rules can serve as a starting point that could be adapted to local conditions. However, creating a much-nuanced adaptation of these rules could be counterproductive, because the strength of the Monte Carasso urban code lies in its concise synthesis, which is only supplemented by the contribution of the expert commission. The danger of unification of the built environment in many towns as a result of applying similar provisions is a potential problem. However, it seems that despite the significant differences in geographical and cultural contexts, urban/architectural patterns at a basic level (such as those governed by the urban code) are very similar across Europe. Therefore, it should not be a problem for similar provisions to regulate many towns within one region or even a country. It is the role of a commission to skillfully guide it toward distinguishable identities.

- 7.

- Special projects: The implementation of the new planning procedure accompanied by significant special projects proved to be an effective method that is worth repeating. The necessity to invest public money in this type of project is facilitated in the European context by the possibility of applying for targeted subsidies from the European Union (EU). Subsidies for this type of project (particularly the renovation of public spaces in small towns) have been (and are) awarded, as part of a Cohesion Fund [58] or Regional Development Fund [59], particularly in the poorer regions of the EU. Moreover, projects financed in this way were often carried out randomly, without substantive justification [60,61,62], which resulted in questionable quality. Including them in a larger, more structured, and well-thought-out procedure could be beneficial. Such public realizations could become part of a larger project and could be continued in the form of a sophisticated urban policy. It could ensure long-lasting results. Such sustained results, which may be called revitalization, are the intended goal of EU financial support. In the proposed scheme, the role of the leader and the advisory committee would be to prepare this type of investment. This could be accomplished by consulting and selecting its location, organizing a competition, or through a design process, until the commencement of implementation. This means that the creation of an appropriate committee should precede any design and implementation activities—unlike in Monte Carasso.

- 8.

- Sample projects: The existence of appropriate individual projects could be difficult, as it would require encouraging private investors to break down established patterns of thought and action, and experiment by themselves. The model of compact living within the core of a historic town is now less acceptable (or even considered obsolete) than the scattered and suburban model. Perhaps a chance for such exemplary projects in the first phase would be municipal social housing.

- 9.

- Design Seminar: The emergence of a substantive—and at the same time open—discussion on the town spaces provided by student workshops is important from the point of view of the durability of the effects and appropriate social acceptance of the policy pursued. Certain involvement of the local community in these seminars is especially desirable. It would be helpful in reaching a democratic consensus that could counterbalance, to a certain extent, the predominant role of a single leader (Snozzi in the original case).

- 10.

- New urban fabric: An important condition for the success of the process is a critical mass effect. This means a moment when new investments created under the urban code (together with the carried-out special projects) create a compact space or at least a fragment of it. They could be perceived as examples of a renewed, urban quality. Only a promising initial effect would allow the operation to continue. Therefore, a necessary condition is the pre-existence of a certain investment dynamic. Firstly, this means that towns suitable for the introduction of the new planning policy are those characterized by a significant construction initiative, and secondly, that there must be certain restrictions on the expansion of the urbanized zone in order to stimulate their internal compaction.

- 11.

- Outcomes: Cooperation between municipalities is also important, mainly as an exchange of experiences, mutual support, and encouragement. It is also important in the context of the stiffness of the mechanism—while introducing initially controversial compactness, the challenge is to avoid unconvinced investors turning away to build in neighboring towns, where such regulations would not exist.

6. Conclusions

- Two-stage urban regulation: universal written rules and decisions of an expert commission;

- Simplicity: low number of rules and clear wording;

- Regulatory humanism: precise (numerical) provisions, apart from imprecise ones (referring to general concepts and subject to interpretation);

- Subjectivity: making the shape of the space dependent on the subjective opinions of a group of experts;

- Form-based orientation: treating the built form (urban morphology) as the most important planning goal that eventually determines usage and social character;

- Limited manual control: individual special design for priority locations within the town (center and suburbs);

- Specific understanding of heritage: priority of structure (topography, urban patterns, parceling geometry) and typo–morphology (the relationship between building and open space) in relation to form, style, and substance;

- Opening the professional discussion on the town’s urban development to the architects and students of architecture.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knox, P.; Meyer, H. Small Town Sustainability: Economic, Social, and Environmental Innovation; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Hamdouch, A. Small and medium-sized towns in Europe: Conceptual, methodological and policy issues. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat—United Nations Human Settlements Programme. World Cities Report; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Strijker, D. Marginal lands in Europe—Causes of decline. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2005, 6, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănică, A.; Istrate, M.; Tudora, D. (N)ever Becoming Urban? The Crisis of Romania’s Small Towns. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, B.; Kwiatek-Sołtys, A.; Kurek, S. Does the process of shrinking concern also small towns? Lessons from Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 91–105. Available online: https://doi-1org-1000098l80ac7.eczyt.bg.pw.edu.pl/10.2478/quageo-2019-0039 (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Fonseca, M.L. New waves of immigration to small towns and rural areas in Portugal. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeroni, M. Industrial decline and resilience in small towns: Evidence from three European case studies. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirisi, G.; Trócsányi, A. Shrinking small towns in hungary: The factors behind the urban decline in” small scale”. Acta Geogr. Univ. Comen. 2014, 58, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, P.; Elis, V.; Müller, B.; Yamamoto, K. Peripheralisation of small towns in Germany and Japan–Dealing with economic decline and population loss. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, N.; Hart, T. Planning for Small Town Change; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, J.-D. The managerial turn and municipal land-use planning in Switzerland—Evidence from practice, Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Jayne, M. Small cities? Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 683–699. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, H.; Knox, P. Small-town sustainability: Prospects in the second modernity. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinführer, A.; Vaishar, A.; Zapletalová, J. The Small Town in Rural Areas as an Underresearched Type of Settlement. Editors’ introduction to the Special Issue. Eur. Countrys. 2016, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meili, R.; Mayer, H. Small and medium-sized towns in Switzerland: Economic heterogeneity, socioeconomic performance and linkages. Erdkunde 2017, 71, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disch, P. Luigi Snozzi: Costuzioni e Progetti; ADV Publishing: Lugano, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Snozzi, L. Monte Carasso: La Reinvenzione del Sito; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bologna, A. Luigi Snozzi e l’utopia realizzata a Monte Carasso (Canton Ticino): IL villaggio rurale divenuto centro: 1979–2009. Storia Urbana 2014, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzati, G.; Lo Conte, A. Luigi Snozzi a Monte Carasso; Maggioli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrycz, P. The role and responsibility of an architect in small town. In Education for Research—Research for Creativity; Słyk, J., Bezerra, L., Eds.; Wydział Architektury Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; pp. 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. Big data, smart cities and city planning. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2013, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropf, K. Urban tissue and the character of towns. Urban Des. Int. 1996, 1, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, E.; Eberle, D. Density & Atmosphere; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, I. A typomorphological approach to design: The plan for St Gervais. Urban Des. Int. 1999, 4, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, I.; Pattacini, L. From description to prescription: Reflections on the use of a morphological approach in design guidance. Urban Des. Int. 1997, 2, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.; Silva, M.; Samuels, I. Urban morphological research and planning practice: A Portuguese assessment. Urban Morphol. 2014, 18, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L. Chinese Urban Design: The Typomorphological Approach. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, T. Planning Practice and the Shaping of the Urban Pattern. In Teaching Urban Morphology; Oliveira, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. Learning from Italian Typology- and Morphology-Led Planning Techniques: A Planning Framework for Yingping, Xiamen. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talen, E. Design by the rules: The historical underpinnings of form-based codes. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V. The Study of Urban Form: Different Approaches. In Urban Morphology; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A. Planning Small and Mid-Sized Towns: Designing and Retrofitting for Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Open Street Map. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- QGIS Software. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- QuickOSM. Available online: https://docs.3liz.org/QuickOSM/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- ORS Tools Plugin. Available online: https://github.com/GIScience/orstools-qgis-plugin/wiki/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained: Urban-Rural Typology. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Urban-rural_typology) (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a Way of Life. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxiadis, C.A. Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Croset, P.A. Luigi Snozzi and Monte Carasso: A long running experiment. Luigi Snozzi, sul progetto di Monte Carasso. Casabella 1984, 506, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Snozzi, L. Auf den Spuren des Ortes; Museum für Gestaltung: Zuerich, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schwick, C.; Jaeger, J.A.G.; Bertiller, R. Urban Sprawl in Switzerland—Unstoppable? Quantitative Analysis 1935 to 2002 and Implications for Regional Planning; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- TUM, Gruppo di lavoro VAI. Modelli di Insediamento Alpino. Progetti Urbanistici Modello|Qualità Esemplari Specifiche; Comunita di Lavore delle Regioni Alpine: Bolzano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus, J. Do municipal autonomy and institutional fragmentation stand in the way of antisprawl policies? A qualitative comparative analysis of Swiss cantons. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1622–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, R. “…al di là dell’orizzonte c’è la città”—Omaggio a Luigi Snozzi; Lecture. Available online: https://vimeo.com/519563182 (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Larsson, G. Spatial Planning Systems in Western Europe: An Overview; IOS Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Confederation. Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, of 18 April 1999 (Status as of 7 March 2021). Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1999/404/en#art_75 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Swiss Confederation. Federal Act on Spatial Planning (Spatial Planning Act, SPA), of 22 June 1979 (Status as of 1 January 2019). Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1979/1573_1573_1573/en (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- IL Gran Consiglio della Repubblica e Cantone Ticino. Legge Cantonale di Applicazione della Legge Federale sulla Pianificazione del Territorio (del 23 Maggio 1990). Available online: https://www.lexfind.ch/tolv/120246/it (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Muggli, R. Spatial Planningi Switzerland: A Short Introduction; Swiss Planing Association VLP-ASPAN: Bern, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mahaim, R. Le Principe de Durabilite’ et L’ame’Nagement du Territoire. Le Mitage du Territoire àL’épreuve du Droit; Schulthess: Geneve, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Monte Carasso. Norme di Attuazione del Piano Regolatore del Comune di Monte Carasso; REGNAPR. 1992. Available online: https://www.bellinzona.ch/downdoc.php?id_doc=50491&lng=1&i=1&rif=0f0fe771bb (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- El-Geneidy, A.; Grimsrud, M.; Wasfi, R.; Tétreault, P.; Surprenant-Legault, J. New evidence on walking distances to transit stops: Identifying redundancies and gaps using variable service areas. Transportation 2014, 41, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Porta, S.; Romice, O. The “neighborhood unit” on trial: A case study in the impacts of urban morphology. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 8, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snozzi, L.; Merlini, F. L’architettura Inefficiente; Edizioni Sottoscala: Bellinzona, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. Cohesion Fund 2014–2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/cohesion-fund/2014-2020 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- European Commision. European Regional Development Fund 2014–2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/erdf/2014-2020 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Bradley, J. Evaluating the impact of European Union Cohesion policy in less-developed countries and regions. Reg. Stud. 2006, 40, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komornicki, T.; Szejgiec-Kolenda, B.; Degórska, B.; Goch, K.; Śleszyński, P.; Bednarek-Szczepańska, M.; Siłka, P. Spatial planning determinants of cohesion policy implementation in Polish regions. Eur. XXI 2018, 35, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E. Assessing Territorial Impacts of the EU Cohesion Policy: The Portuguese Case. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1960–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasc. Luigi Snozzi Cittadinanza Onoraria. Available online: https://www.carasc.ch/Luigi-Snozzi-cittadinanza-onoraria-2e233c00 (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Cullen, G. Concise Townscape; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| UA | P | PD | NB | BpA | ƩBA | BuD | BFmn | BFmd | NB>500 | NB>2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ha] | [1/ha] | [1/ha] | [m2] | [m2] | [m2] | ||||||

| Monte Carasso | 46.57 | 2872 | 62 | 495 | 10.63 | 82,683 | 0.18 | 167 | 145 | 10 | 0 |

| Sementina | 69.61 | 3217 | 46 | 553 | 7.94 | 117,680 | 0.17 | 212 | 159 | 20 | 4 |

| A. Town Hall as FP | B. Centroid as FP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA | A5min | IA5min | NB5min | A5min | IA5min | NB5min | |

| [ha] | [ha] | [1/ha] | [ha] | [1/ha] | |||

| Monte Carasso | 46.57 | 22.72 | 49% | 260 | 31.88 | 68% | 380 |

| Sementina | 69.61 | 30.11 | 43% | 260 | 36.42 | 52% | 262 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedrycz, P. Form-Based Regulations to Prevent the Loss of Urbanity of Historic Small Towns: Replicability of the Monte Carasso Case. Land 2021, 10, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111235

Pedrycz P. Form-Based Regulations to Prevent the Loss of Urbanity of Historic Small Towns: Replicability of the Monte Carasso Case. Land. 2021; 10(11):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111235

Chicago/Turabian StylePedrycz, Paweł. 2021. "Form-Based Regulations to Prevent the Loss of Urbanity of Historic Small Towns: Replicability of the Monte Carasso Case" Land 10, no. 11: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111235

APA StylePedrycz, P. (2021). Form-Based Regulations to Prevent the Loss of Urbanity of Historic Small Towns: Replicability of the Monte Carasso Case. Land, 10(11), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111235