Mountain Landscape Preferences of Millennials Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study on Western Sichuan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

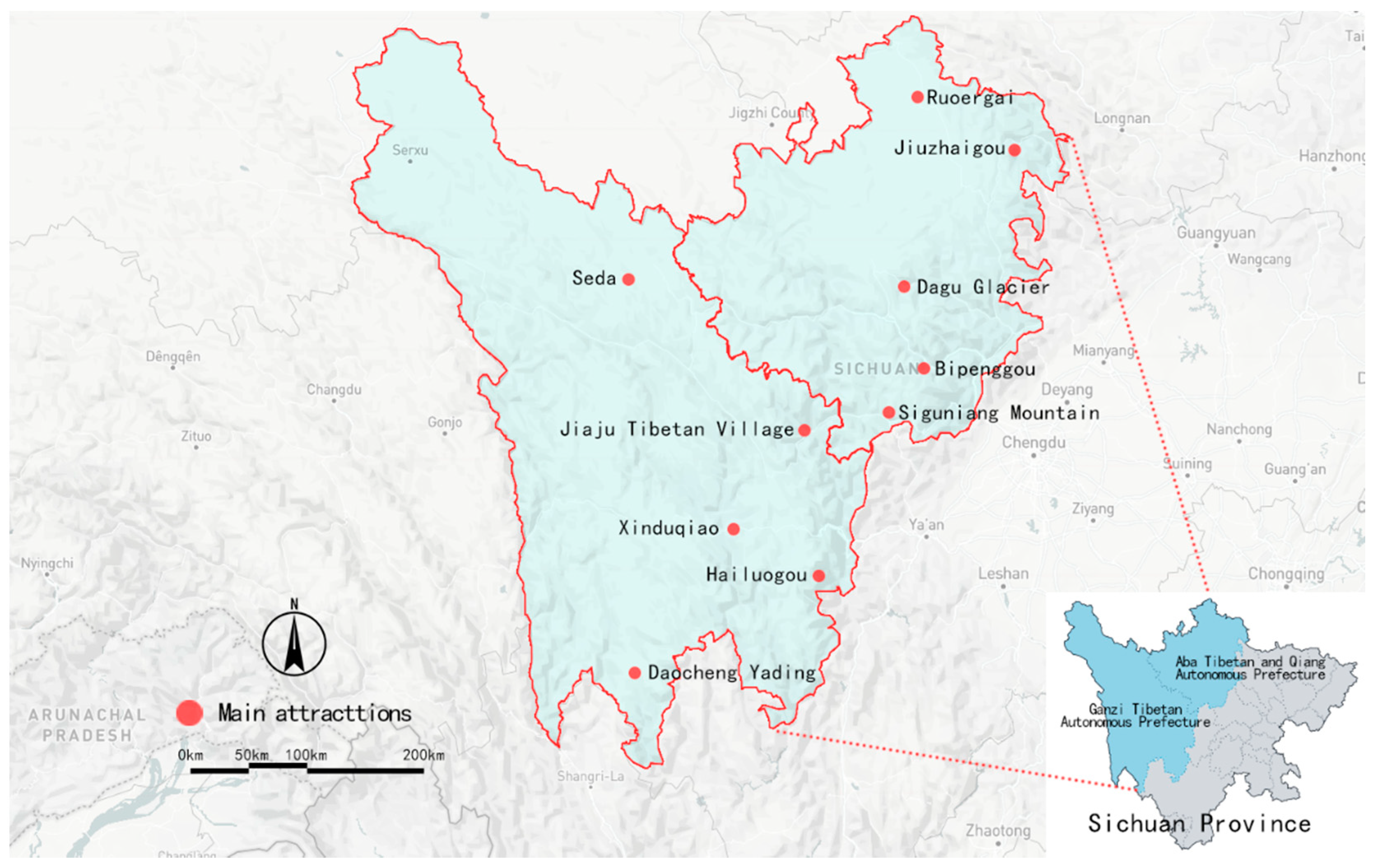

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Statistics

3. Result

3.1. Statistical Characteristics of Millennial Tourists

3.2. Photo Statistics

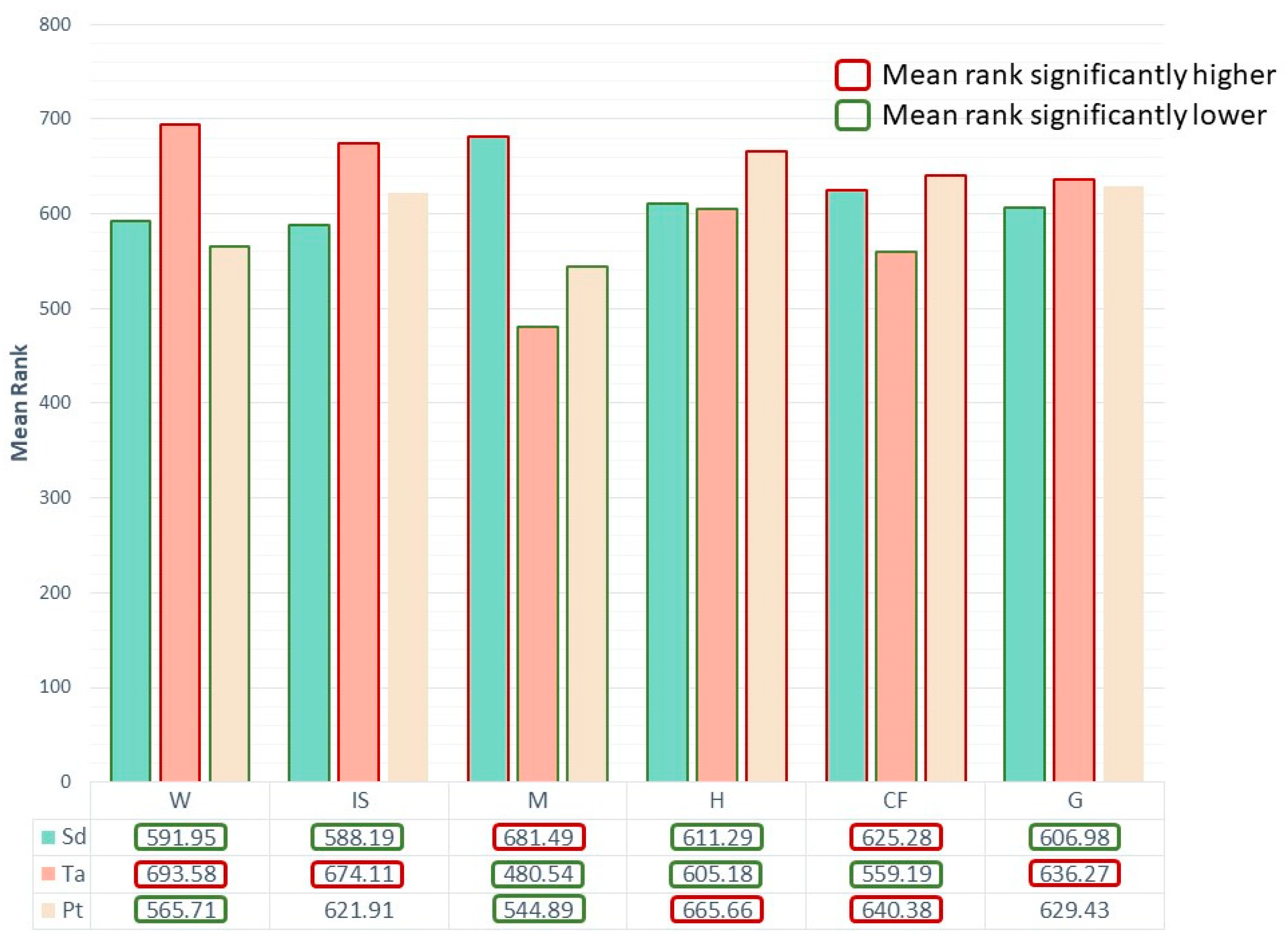

3.3. Analysis of Millennials’ Landscape Preferences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Gender | Transportation | Travel Pattern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Mean Rank | SE | Item | Mean Rank | SE | Item | Mean Rank | SE | |

| NL | Male | 616.04 | 0.414 | Sd | 616.44 | 0.308 | Ind | 587.96 | 0.357 |

| Female | 615.19 | 0.255 | Cy | 688.96 | 0.842 | Wf | 605.82 | 0.326 | |

| Ta | 631.12 | 0.398 | Wfm | 687.26 | 0.705 | ||||

| Pt | 575.18 | 0.478 | Cp | 638.18 | 0.613 | ||||

| HL | Male | 604.22 | 0.236 | Sd | 610.32 | 0.161 | Ind | 643.00 | 0.251 |

| Female | 622.01 | 0.135 | Cy | 618.22 | 0.233 | Wf | 634.05 | 0.182 | |

| Ta | 594.05 | 0.194 | Wfm | 478.02 | 0.143 | ||||

| Pt | 673.23 | 0.386 | Cp | 615.60 | 0.339 | ||||

| F | Male | 626.57 | 0.137 | Sd | 600.22 | 0.103 | Ind | 596.10 | 0.125 |

| Female | 609.11 | 0.091 | Cy | 656.02 | 0.308 | Wf | 613.20 | 0.111 | |

| Ta | 644.75 | 0.150 | Wfm | 689.90 | 0.242 | ||||

| Pt | 632.21 | 0.182 | Cp | 593.98 | 0.217 | ||||

| W | Male | 541.74 | 0.123 | Sd | 591.95 | 0.095 | Ind | 651.32 | 0.134 |

| Female | 658.06 | 0.093 | Cy | 829.38 | 0.349 | Wf | 605.52 | 0.107 | |

| Ta | 693.58 | 0.161 | Wfm | 648.14 | 0.252 | ||||

| Pt | 565.71 | 0.192 | Cp | 563.54 | 0.193 | ||||

| IS | Male | 607.47 | 0.213 | Sd | 588.19 | 0.153 | Ind | 688.22 | 0.218 |

| Female | 620.13 | 0.141 | Cy | 777.30 | 0.533 | Wf | 585.63 | 0.172 | |

| Ta | 674.11 | 0.256 | Wfm | 630.57 | 0.342 | ||||

| Pt | 621.91 | 0.292 | Cp | 590.25 | 0.335 | ||||

| BL | Male | 632.47 | 0.149 | Sd | 606.46 | 0.106 | Ind | 604.64 | 0.113 |

| Female | 605.71 | 0.087 | Cy | 741.50 | 0.340 | Wf | 613.32 | 0.119 | |

| Ta | 631.03 | 0.149 | Wfm | 671.68 | 0.247 | ||||

| Pt | 613.08 | 0.182 | Cp | 594.37 | 0.201 | ||||

| Md | Male | 622.35 | 0.134 | Sd | 681.49 | 0.109 | Ind | 488.41 | 0.076 |

| Female | 611.55 | 0.090 | Cy | 523.16 | 0.154 | Wf | 627.59 | 0.107 | |

| Ta | 480.54 | 0.092 | Wfm | 676.99 | 0.277 | ||||

| Pt | 544.89 | 0.118 | Cp | 736.25 | 0.232 | ||||

| Wt | Male | 665.99 | 0.107 | Sd | 615.56 | 0.099 | Ind | 659.52 | 0.184 |

| Female | 586.37 | 0.089 | Cy | 580.08 | 0.265 | Wf | 605.57 | 0.081 | |

| Ta | 593.27 | 0.100 | Wfm | 575.13 | 0.184 | ||||

| Pt | 656.24 | 0.163 | Cp | 611.74 | 0.201 | ||||

| H | Male | 639.89 | 0.068 | Sd | 611.29 | 0.041 | Ind | 615.95 | 0.065 |

| Female | 601.43 | 0.030 | Cy | 519.00 | 0.000 | Wf | 638.90 | 0.046 | |

| Ta | 605.18 | 0.040 | Wfm | 531.89 | 0.024 | ||||

| Pt | 665.66 | 0.119 | Cp | 597.76 | 0.100 | ||||

| CF | Male | 596.41 | 0.046 | Sd | 625.28 | 0.037 | Ind | 676.94 | 0.051 |

| Female | 626.51 | 0.032 | Cy | 756.34 | 0.187 | Wf | 601.15 | 0.040 | |

| Ta | 559.19 | 0.038 | Wfm | 563.90 | 0.053 | ||||

| Pt | 640.38 | 0.067 | Cp | 608.02 | 0.069 | ||||

| A | Male | 623.02 | 0.126 | Sd | 610.51 | 0.090 | Ind | 606.90 | 0.152 |

| Female | 611.16 | 0.081 | Cy | 501.96 | 0.174 | Wf | 645.27 | 0.103 | |

| Ta | 617.21 | 0.122 | Wfm | 497.40 | 0.073 | ||||

| Pt | 652.45 | 0.218 | Cp | 618.82 | 0.174 | ||||

| FC | Male | 621.18 | 0.029 | Sd | 637.96 | 0.023 | Ind | 596.35 | 0.029 |

| Female | 612.22 | 0.022 | Cy | 556.96 | 0.080 | Wf | 625.26 | 0.027 | |

| Ta | 563.95 | 0.035 | Wfm | 575.29 | 0.052 | ||||

| Pt | 604.54 | 0.045 | Cp | 646.03 | 0.040 | ||||

| G | Male | 606.94 | 0.028 | Sd | 606.98 | 0.018 | Ind | 607.47 | 0.022 |

| Female | 620.44 | 0.016 | Cy | 559.00 | 0.000 | Wf | 625.19 | 0.024 | |

| Ta | 636.27 | 0.030 | Wfm | 576.86 | 0.025 | ||||

| Pt | 629.43 | 0.041 | Cp | 625.75 | 0.036 | ||||

| Variable | (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I–J) | Std. Error | Adjusted Sig. | (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I–J) | Std. Error | Adjusted Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL | Ind | Wfm | −99.302 | 36.301 | 0.0037 | |||||

| HL | Wfm | Cp | −137.577 | 38.187 | 0.002 | |||||

| Wfm | Wf | 156.024 | 31.037 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Wfm | Ind | 164.974 | 34.287 | 0.000 | ||||||

| W | Pt | Ta | 124.823 | 33.411 | 0.001 | |||||

| Sd | Ta | −98.870 | 24.060 | 0.000 | ||||||

| IS | Sd | Ta | −83.555 | 23.857 | 0.001 | Wf | Ind | 102.589 | 24.505 | 0.000 |

| Cp | Ind | 97.964 | 33.525 | 0.021 | ||||||

| M | Sd | Ta | −196.417 | 21.865 | 0.000 | Ind | Wf | −139.184 | 22.395 | 0.000 |

| Pt | Sd | 133.764 | 26.320 | 0.000 | Ind | Wfm | −188.580 | 32.225 | 0.000 | |

| Ind | Cp | −247.845 | 30.639 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Wf | Cp | −108.661 | 27.408 | 0.000 | ||||||

| H | Ta | Pt | −59.430 | 21.824 | 0.019 | Wfm | Ind | 84.062 | 22.994 | 0.002 |

| Sd | Pt | 53.325 | 18.919 | 0.014 | Wfm | Wf | 107.007 | 20.815 | 0.000 | |

| CF | Ta | Sd | 64.642 | 17.072 | 0.000 | Wfm | Ind | 113.042 | 25.438 | 0.000 |

| Ta | Pt | −79.594 | 23.707 | 0.002 | Wf | Ind | 75.793 | 17.679 | 0.000 | |

| Cp | Ind | 68.926 | 24.186 | 0.026 | ||||||

| A | Wfm | Ind | 109.495 | 32.049 | 0.004 | |||||

| Wfm | Cp | −121.415 | 35.694 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Wfm | Wf | 147.863 | 29.011 | 0.000 | ||||||

| FC | Ta | Sd | 72.510 | 14.850 | 0.000 | Wfm | Cp | −70.737 | 24.254 | 0.021 |

| G | Wfm | Wf | 48.331 | 16.473 | 0.020 |

References

- Tian, J.; Ming, Q. Hotspots, progress and enlightenments of foreign mountain tourism research. World Reg. Stud. 2020, 29, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; Shi, X. Study on Characteristic Development Strategies of Mountain Tourism in High Mountain Canyon Area of Hengduan Mountains in Sichuan—Exploring the Development Path of Mountain Tourism in Western China. Econ. Ggography 2012, 32, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delitheou, V.; Alexiou, S. Challenges of Tourism Sustainability in Greek Mountain Regions in Decline. AJHSSR 2021, 5, 448–458. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350889823 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Paunović, I.; Jovanović, V. Implementation of Sustainable Tourism in the German Alps: A Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rita, P.; Brochado, A.; Dimova, L. Millennials’ Travel Motivations and Desired Activities within Destinations: A Comparative Study of the US and the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2034–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, A. From sublime landscapes to white gold: How skiing transformed the Alps after 1930. Environ. Hist. 2014, 19, 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; Truant, E.; Bonadonna, A. Mountain Tourism and Motivation: Millennial Students’ Seasonal Preferences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 2461–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkes, C.A. Farmers’ Markets: A Case for Culinary Tourism. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2012, 10, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.; Makens, J.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 7th ed.; Global Edition; Pearson: London, UK, 2017; p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, N.; Falk, J. Tourism and identity-related motivations: Why am I here (and not there)? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 15, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. Identity and the art museum visitor. J. Art Educ. 2018, 34, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Chasing a myth? Searching for ‘self’ through lifestyle travel. Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michael, N.; Nyadzayo, M.W.; Michael, I.; Balasubramanian, S. Differential roles of push and pull factors on escape for travel: Personal and social identity perspectives. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, D.K.; Stoffman, D. Boom, Bust and Echo 2000: Profiting from the Demographic Shift in the New Millennium; Macfarlane, Walter & Ross: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, L.; Thach, L.; Olsen, J.E. Wowing the Millennials: Creating Brand Equity in the Wine Industry. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2006, 15, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benckendorff, P.; Moscardo, G.; Pendergast, D. Generation Y and travel. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, M. Millennials, Sharing Economy and Tourism: The Case of Seoul. J. Tour. Futures 2018, 4, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonadonna, A.; Giachino, C.; Truant, E. Sustainability and Mountain Tourism: The Millennial’s Perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buckley, R. Sustainability issues in mountain tourism. In Sustainable Mountain Communities; Taylor, L., Ryall, A., Eds.; The Banff Centre: Banff, CAN, 2003; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, J.; Thompson-Carr, A.; Musa, G. Activity, People and Place. In Mountaineering Tourism; Musa, G., Higham, J., Thompson-Carr, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavagnaro, E.; Staffieri, S. A Study of Students’ Travellers Values and Needs in Order to Establish Futures Patterns and Insights. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D. Destabilising Automobility? The Emergent Mobilities of Generation Y. Ambio 2017, 46, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding and Developing Visitor pro-Environmental Behaviors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.E.; Thach, L.; Nowak, L. Wine for My Generation: Exploring How Us Wine Consumers Are Socialized to Wine. J. Wine Res. 2007, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoolman, E.D.; Shriberg, M.; Schwimmer, S.; Tysman, M. Green Cities and Ivory Towers: How Do Higher Education Sustainability Initiatives Shape Millennials’ Consumption Practices? J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieskens, K.F.; Van Zanten, B.T.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verburg, P.H. Aesthetic appreciation of the cultural landscape through social media: An analysis of revealed preference in the dutch river landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 117, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Martín-López, B.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Using Social Media Photos to Explore the Relation between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Landscape Features across Five European Sites. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young Travelers’ Intention to Behave pro-Environmentally: Merging the Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Expectancy Theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Fung, B.C.M.; Chen, Z. Young Chinese Consumers’ Choice between Product-Related and Sustainable Cues-the Effects of Gender Differences and Consumer Innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, A.; Tengxiage, A.; Kadijk, H.; Wright, A.J. Exploring Chinese Millennials’ Experiential and Transformative Travel: A Case Study of Mountain Bikers in Tibet. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of Social Media in Online Travel Information Search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.T.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Li, B. Millennial Tourists’ Environmentally Sustainable Behavior towards a Natural Protected Area: An Integrative Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Shao, L.; Cui, J.; Meng, X. The structure of pull motivations of rural tourism and the segmentation of rural tourists. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2014, 28, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettebone, D.; Newman, P.; Lawson, S.R.; Hunt, L.; Monz, C.; Zwiefka, J. Estimating Visitors’ Travel Mode Choices along the Bear Lake Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1210–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Cheng, A.J.; Hsu, W.H. Travel recommendation by mining people attributes and travel group types from community-contributed photos. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2013, 15, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, M.-I.; Istudor, L.-G. The Role of Social Media and User-Generated-Content in Millennials’ Travel Behavior. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 7, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdeji, I.; Dragin, A. Is Cruising along European Rivers Primarily Intended for Seniors and Workers from Eastern Europe? Geogr. Pannonica 2017, 21, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fall, L.T.; Lubbers, C.A. Promoting America: How Do College-Age Millennial Travelers Perceive Terms for Branding the USA? In Global Place Branding Campaigns across Cities, Regions, and Nations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loda, M.D.; Coleman, B.C.; Backman, K.F. Walking in Memphis: Testing One DMO’s Marketing Strategy to Millennials. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, S.; Inger, R.; Desilvey, C.; Gaston, K.J. Spatial covariance between aesthetic value & other ecosystem services. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wood, S.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Silver, J.M.; Lacayo, M. Using Social Media to Quantify Nature-Based Tourism and Recreation. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlieder, C.; Matyas, C. Photographing a city: An analysis of place concepts based on spatial choices. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2009, 9, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, B.T.; Van Berkel, D.B.; Meentemeyer, R.K.; Smith, J.W.; Tieskens, K.F.; Verburg, P.H. Continental-Scale Quantification of Landscape Values Using Social Media Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12974–12979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richards, D.R.; Friess, D.A. A Rapid Indicator of Cultural Ecosystem Service Usage at a Fine Spatial Scale: Content Analysis of Social Media Photographs. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 53, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.R.; Tunçer, B. Using image recognition to automate assessment of cultural ecosystem services from social media photographs. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 31, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenerelli, P.; Demšar, U.; Luque, S. Crowdsourcing Indicators for Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Geographically Weighted Approach for Mountain Landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hausmann, A.; Toivonen, T.; Slotow, R.; Tenkanen, H.; Moilanen, A.; Heikinheimo, V.; Di Minin, E. Social media data can be used to understand tourists’ preferences for nature-based experiences in protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirilenko, A.P.; Stepchenkova, S.O. Sochi 2014 Olympics on Twitter: Perspectives of Hosts and Guests. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Schönberger, V.; Cukier, K. Big data: A revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think. J. Epid. 2014, 179, 1143–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle, N.; Pentland, A.; Lazer, D. Inferring Friendship Network Structure by Using Mobile Phone Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 15274–15278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. by Klaus Krippendorff. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1984, 79, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B. Description of communication content characteristics test of communication research hypothesis content analysis method. Contemp. Commun. 1999, 6, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Dong, S.; Xue, M. Ecotourism model and benefit analysis in the marginal areas of ethnic minorities in Western Sichuan. Rural. Econ. 2008, 3, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Trade-Offs between Sustainable Tourism Development Goals: An Analysis of Tibet (China). Sustain. Dev 2019, 27, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, S.; Li, B.; Jin, X. Research on Eco-tourism Development Patterns in the Ethnic Regions of Western Sichuan Province under the Comprehensive Tourism Strategy. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2009, 19, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Konu, H.; Laukkanen, T. Predictors of Tourists’ Wellbeing Holiday Intentions in Finland. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Alsawafi, A. Sport Tourism: An Exploration of the Travel Motivations and Constraints of Omani Tourists. Anatolia 2017, 28, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanmei, C. Summarization of Human Tourism Resources in Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. J. Sichuan Univ. Natl. 2013, 22, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; Shi, Q.; Anayeti, A.; Liu, M.; Change, S. Landscape Classification System Based on Climate, Landform, Ecosystem: A Case Study of Xinjiang Area. Shengtai Xuebao/Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 3359–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, A.M.; Guadagno, R.E.; Muscanell, N.L.; Dill, J. Gender Differences in Mediated Communication: Women Connect More than Do Men. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Rashidi, T.H.; Vij, A. X vs. Y: An Analysis of Intergenerational Differences in Transport Mode Use among Young Adults. Transportation 2020, 47, 2203–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teles da Mota, V.; Pickering, C. Using Social Media to Assess Nature-Based Tourism: Current Research and Future Trends. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 30, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Morgan, M.; Song, P. Students’ Travel Behavior: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of UK and China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Litt, E. The tweet smell of celebrity success: Explaining variation in Twitter adoption among a diverse group of young adults. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L. Cultural Tourism in an Ethnic Theme Park: Tourists’ Views. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2011, 9, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Qi, Q. Domestic Tourism Demand of Urban and Rural Residents in China: Does Relative Income Matter? Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Parkins, J.R.; Sherren, K. Using Geo-Tagged Instagram Posts to Reveal Landscape Values around Current and Proposed Hydroelectric Dams and Their Reservoirs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 170, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J. The New Environmental Paradigm and Nature-Based Tourism Motivation. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Category | Subcategory | Landscape Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Natural landscape | Forest | Alpine forest, Low mountain forest, Virgin forest, Slow slope forest |

| Waterscape | Lake, River | |

| Ice and snow | Snow mountain, Snow covered land | |

| Bare land | River beach stone land, Alpine region | |

| Meadow | Sloping fields meadow, Lowland meadow, Pasture meadow, Wild grassland, Lowland meadow | |

| Weather | Sunrise, Sunset, Seas of clouds | |

| Human landscape | Heritage | Building heritage |

| Customs and Festivals | Ethnic customs, Ethnic art, Celebrations, Clothing | |

| Architecture | Residential building, Temple, Villages and towns, Diaolou structure | |

| Folk culture | Folk belief, Religious belief | |

| Gastronomy | Food, Gastronomy esthetic, Dining environment |

| Item | N | Total | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| natural landscape | 1230 | 18,328 | 14.9 |

| human landscape | 1230 | 3039 | 2.47 |

| forest | 1230 | 3748 | 3.05 |

| waterscape | 1230 | 3104 | 2.52 |

| ice and snow | 1230 | 4359 | 3.54 |

| bare land | 1230 | 2869 | 2.33 |

| meadow | 1230 | 1898 | 1.54 |

| weather | 1230 | 2350 | 1.91 |

| heritage | 1230 | 475 | 0.39 |

| customs and festivals | 1230 | 480 | 0.39 |

| architecture | 1230 | 1670 | 1.36 |

| folk culture | 1230 | 255 | 0.21 |

| gastronomy | 1230 | 159 | 0.13 |

| Types | Item | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 450 | 36.6 |

| Female | 780 | 63.4 | |

| Transportation | Self-driving | 767 | 62.4 |

| Cycling | 25 | 2 | |

| Travel agency | 270 | 22 | |

| Public transportation | 168 | 13.7 | |

| Travel pattern | Individual | 288 | 23.4 |

| With friends | 632 | 51.4 | |

| With family members | 143 | 11.6 | |

| Couples | 167 | 13.6 |

| Variable | NL | HL | F | W | IS | BL | M | Wt | H | CF | A | FC | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.002 | 0.803 | 0.708 | 31.992 | 0.385 | 1.708 | 0.336 | 15.289 | 8.358 | 4.181 | 0.409 | 0.505 | 1.645 |

| Transportation | 3.768 | 6.275 | 4.050 | 30.09 | 18.188 | 4.394 | 93.808 | 3.749 | 13.813 | 24.736 | 5.823 | 26.704 | 8.992 |

| Travel pattern | 8.736 | 27.933 | 7.977 | 8.583 | 18.734 | 4.704 | 77.800 | 7.233 | 27.675 | 25.997 | 26.262 | 12.195 | 9.766 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, K.; Yang, M.; Luo, S. Mountain Landscape Preferences of Millennials Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study on Western Sichuan. Land 2021, 10, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111246

Ding K, Yang M, Luo S. Mountain Landscape Preferences of Millennials Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study on Western Sichuan. Land. 2021; 10(11):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111246

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Keying, Mian Yang, and Shixian Luo. 2021. "Mountain Landscape Preferences of Millennials Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study on Western Sichuan" Land 10, no. 11: 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111246

APA StyleDing, K., Yang, M., & Luo, S. (2021). Mountain Landscape Preferences of Millennials Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study on Western Sichuan. Land, 10(11), 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111246