Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Research Regarding Community Satisfaction

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Research Method

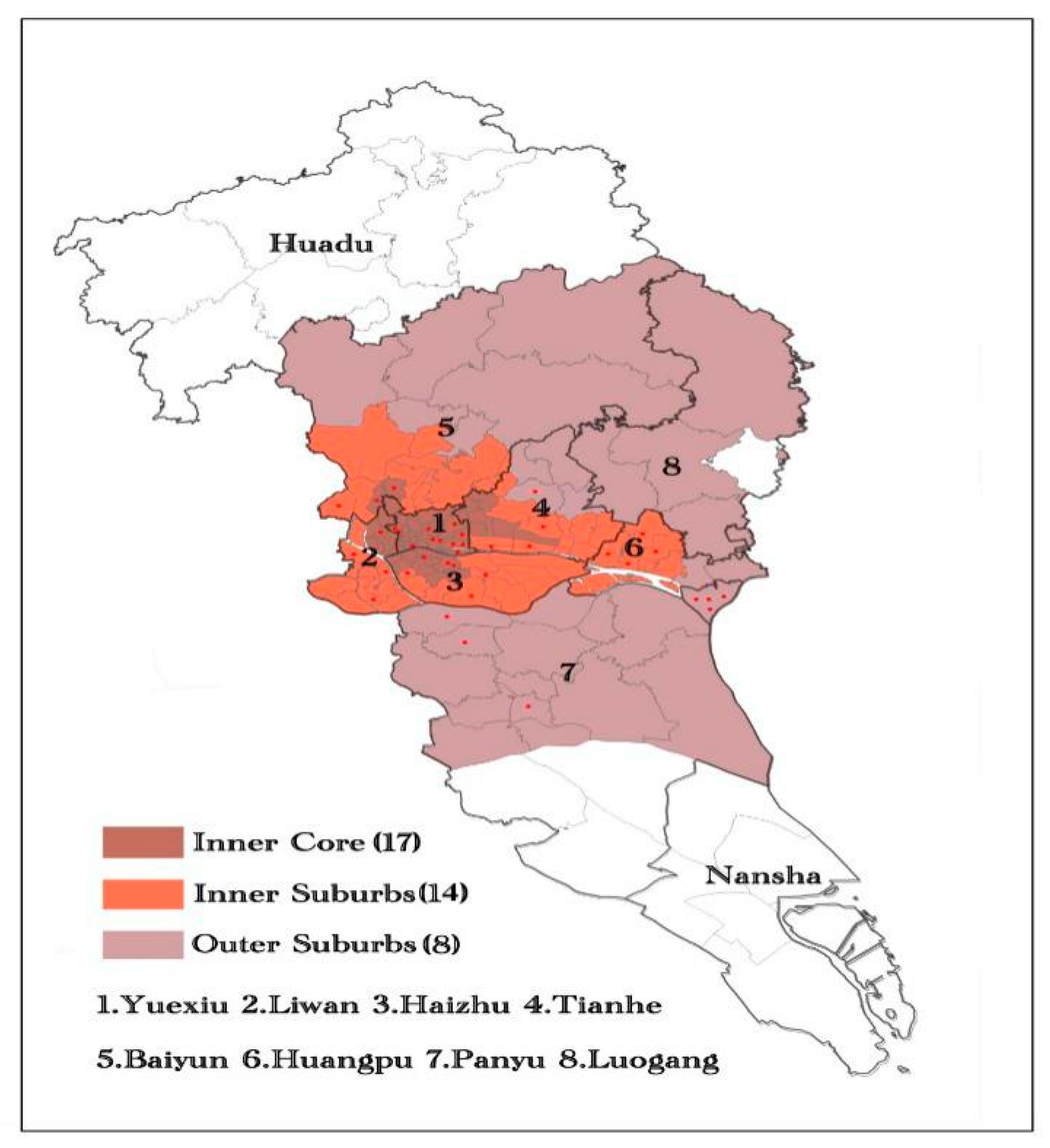

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures of Community Satisfaction and Independent Variables

- i.

- Mobility pattern, i.e., change in housing type. According to the sorting scheme in the literature review, three mobility patterns can be identified: 1. from urban village, public housing and self-settlement to commodity housing community (Upgrade 1), 18.23%; 2. from work-unit/privatized public housing community to community housing community (Upgrade 2), 26.59%; 3. moved between same or similar type of community or from higher-standard community to lower-standard community (Level or Downgrade), 55.18%. Because in the total sample, respondents rarely experience the downgrade move (only 0.48%), we merge the level move and the downgrade move into one type.

- ii.

- Migration direction. It is also represented by three categories, that is inward moves (10.66%), outward moves (17.90%), within-zone moves (71.44%).

- iii.

- The motivation for the move and length of residence. Because of the nature of the survey, motivations of the move are missing. Further studies are needed on this reason in our future research. The average length of residence of the sample is 7.03 years.

4. Empirical Analysis and Findings Discussions

4.1. Level-1 Variables: Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Elements of Mobility Experience

4.2. Level-2 Variables: Characteristics of the Present Neighborhood (Reflection of Aggregated Outcomes of Individuals’ Residential Moves)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Deng, F.F. Residential mobility in Chinese cities: A longitudinal analysis. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 625–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yi, D.; Clark, W.A.V. Multiple Home Ownership in Chinese Cities: An Institutional and Cultural Perspective. Cities 2020, 97, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Lin, Z. China’s Housing Reform and Labor Market Participation. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.B.; Chen, Z.N.; Yan, X.P. Comparisons of Related Characteristics for Residential Mobility in Different Phases in Transitional Guangzhou. Trop. Geogr. 2009, 2, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Mao, S. Exploring residential mobility in Chinese cities: An empirical analysis of Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3718–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mao, S.; Du, H. Residential mobility and neighbourhood attachment in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2019, 51, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, G. Neighbourhood Attachment in Dynamic Perspective: Changing People and Changing Contexts; The Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Residential relocation under market-oriented redevelopment: The process and outcomes in urban China. Geoforum 2004, 35, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Breitung, W.; Li, S. The Changing Meaning of neighborhood Attachment in Chinese Commodity Housing Estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2439–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M.; Song, Y.-L. Redevelopment, Displacement, Housing Conditions, and Residential Satisfaction: A Study of Shanghai. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2009, 41, 1090–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chiang, L.; Li, S. The place attachment of residents displaced by urban redevelopment projects in Shanghai. Issues Stud. 2012, 48, 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, B. Residential satisfaction in traditional and redeveloped innercity neighborhood: A tale of two neighborhoods in Beijing. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Lin, Z. Does housing unaffordability crowd out elites in Chinese superstar cities? J. Hous. Econ. 2019, 45, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, S. Is It Really Just a Rational Choice? The Contribution of Emotional Attachment to Temporary Migrants’ Intention to Stay in the Host City in Guangzhou. China Rev. 2012, 12, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Logan, J. Do rural migrants ‘float’in urban China? Neighbouring and neighborhood sentiment in Beijing. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2973–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, F.; Wang, D. Changes in residential satisfaction after home relocation: A longitudinal study in Beijing, China. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.C.; Hesser, G.W. Residential satisfaction composition a land contextual correlates. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebuarni, R.; Al-Abed, A. Satisfaction level with neighbourhood in low income public housing in Yemen. Prop. Manag. 2000, 18, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, S.; Kaplan, R.; Hunter, M.R. How does perception of nearby nature affect multiple aspects of neighborhood satisfaction and use patterns? Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, D. Environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: An exploration of mismatched neighborhood characteristics in the Twin Cities. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2016, 150, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theodori, G. Community attachment, satisfaction, and action. Community Dev. 2004, 35, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J. What is the ‘neighbourhood’ in neighbourhood satisfaction? Comparing the effects of structural characteristics measured at the micro-neighbourhood and tract levels. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2517–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Cerin, E. Are perceptions of the local environment related to neighborhood satisfaction and mental health in adults? Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amole, D. Residential satisfaction in students’ housing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, Y.S. Residential mobility within Guangzhou city, China, 1990–2010: Local residents versus migrants. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2014, 55, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P. Why Families Move; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.A.V.; Ledwith, V. Mobility, Housing Stress, and Neighbourhood Contexts: Evidence from Los Angeles. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, W.A.V.; Withers, S.D. Family migration and mobility sequences in the United States: Spatial mobility in the context of the life course. Demogr. Res. 2007, 17, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tucker, C.; Marx, J.; Long, L. “Moving on”: Residential mobility and children’s school lives. Sociol. Educ. 1998, 71, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ham, M. Housing behaviour. In Handbook of Housing Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2012; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bolan, M. The mobility experience and neighborhood attachment. Demography 1997, 34, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temelová, J.; Slezáková, A. The changing environment and neighbourhood satisfaction in socialist high-rise panel housing estates: The time-comparative perceptions of elderly residents in Prague. Cities 2014, 37, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, N. Hispanic neighbourhood satisfaction in new and established metropolitan destinations. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2953–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Yip, N. Neighborhood and neighbouring in contemporary Guangzhou. J. Contemp. China 2007, 16, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M. Life Course and Residential Mobility in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2004, 36, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Folmer, H. Determinants of residential satisfaction in urban China: A multi-group structural equation analysis. Urban. Stud. 2016, 54, 1407–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. The complex relationship between neighbourhood types and migrants’ socio-economic integration: The case of urban China. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2019, 35, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B.; Leighton, B. Networks, Neighborhoods, and Communities Approaches to the Study of the Community Question. Urban Aff. Rev. 1979, 14, 363–390. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B.; Wong, D. Changing urban residential patterns of Chinese migrants: Shanghai, 2000–2010. Urban. Geogr. 2015, 36, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wei, Y.D. Population Distribution and Spatial Structure in Transitional Chinese Cities: A Study of Nanjing. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2006, 47, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. Effects of Involuntary Residential Relocation on Household Satisfaction in Shanghai, China. Urban. Policy Res. 2013, 31, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, S.M. Becoming homeowners: The emergence and use of online neighbourhood forums in transitional urban China. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Logan, J.R. Growth on the Edge: The New Chinese Metropolis. In Urban China in Transition; Logan, J.R., Ed.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Corrado, G.; Corrado, L.; Santoro, E. On the Individual and Social Determinants of Neighborhood Satisfaction and Attachment. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flaherty, J.; Brown, R.B. A Multilevel Systemic Model of Community Attachment: Assessing the Relative Importance of the Community and Individual Levels. Am. J. Sociol. 2010, 116, 503–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wu, F. Moving to the Suburbs: Demand-Side Driving Forces of Suburban Growth in China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2013, 45, 1823–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, N.M.; Leung, T.T.F.; Huang, R. Impact of Community on Personal Well-Being in Urban China. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2013, 39, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, F. Housing and land financialization under the state ownership of land in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Stuck in the suburbs? Socio-spatial exclusion of migrants in Shanghai. Cities 2017, 60, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Fu, Q. Deciphering the Civic Virtue of Communal Space Neighborhood Attachment, Social Capital, and Neighborhood Participation in Urban China. Environ. Behav. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Classification | Obs. | Mean/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community satisfaction | 1662 | 3.75 | |

| Personal level | |||

| Age | Years of age (Years) | 1662 | 44.76 |

| Gender | Male | 728 | 43.80 |

| Female | 934 | 56.20 | |

| Hukou | Local | 1188 | 71.48 |

| Non-local | 474 | 28.52 | |

| Income | Family income (ten thousand Yuan) | 1662 | 14.36 |

| Education | Years of schooling (Years) | 1662 | 12.04 |

| Child in house | Yes | 920 | 55.35 |

| No | 742 | 44.65 | |

| Tenure | Yes | 1329 | 79.96 |

| No | 333 | 20.04 | |

| Job rank | Clerical/technical worker | 228 | 13.72 |

| Manual/services worker | 239 | 14.38 | |

| others | 835 | 50.24 | |

| Administration/professional | 359 | 21.60 | |

| Length of residence | Years of residence (Years) | 1662 | 7.19 |

| Mobility pattern | U1: Urban village, self-settlement, privatized public housing-commodity housing | 303 | 18.23 |

| U2: Work-unit/reform housing-Commodity housing | 442 | 26.59 | |

| L or D: Commodity housing-Commodity housing and others | 917 | 55.18 | |

| Migration direction | Inward move (Suburbs-inner city) | 175 | 10.66 |

| Outward move (Inner city-suburbs) | 294 | 17.90 | |

| Within-zone move | 1173 | 71.44 | |

| Community level | |||

| Built environment | 3.51 | ||

| Community composition | Percentage of homeowners | 0.81 | |

| Percentage of migrants | 0.35 | ||

| Community stability | Percentage of people having lived here pass five years | 0.62 | |

| Community scale | Population size of the community | 1967 |

| Percent “Extremely Satisfied” | Mean | Component | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| (a) Transport convenience | 68.42 | 3.83 | 0.536 |

| (b) Overall architectural design | 46.93 | 3.44 | 0.658 |

| (c) Cleaning | 52.86 | 3.50 | 0.790 |

| (d) Responsiveness of estate management company to individual requests | 44.04 | 3.32 | 0.755 |

| (e) Maintenance of public facilities in community (like lifts and water pumps) | 50.06 | 3.43 | 0.783 |

| (f) Responsible security guards | 54.78 | 3.53 | 0.730 |

| Community Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| (Constant) | 3.125 | |

| Level-1 variables | ||

| Age | 0.010 | |

| Gender | 1 = male; 0 = female | 0.047 |

| Hukou | 1 = local; 0 = non-local | 0.081 |

| Income | 0.001 | |

| Education | −0.013 | |

| Child in house | 1 = yes;0 = no | −0.008 |

| Tenure | 1 = homeowner;0 = tenant | 0.061 * |

| Occupation (reference = Manual/services worker) | Clerical/technical worker | −0.005 |

| Administration/professional | 0.099 | |

| others | 0.090 | |

| Length of residence | 0.012 ** | |

| Mobility pattern (reference = Commodity housing-Commodity housing and others) | U1: Urban village, self-settlement, etc.-commodity housing | 0.036 * |

| U2: Work-unit/reform housing-Commodity housing | 0.317 ** | |

| Migration direction (reference = Within-zone move) | Inward move | 0.115 |

| Outward move | −0.586 | |

| Level-2 variables | ||

| Built environment | 0.395 *** | |

| Community composition | Percentage of homeowners | 0.006 * |

| Percentage of migrants | −0.001 | |

| Community stability | 0.072 | |

| Community scale | −0.011 | |

| Interaction terms | ||

| Income×Mobility pattern (reference = L or D: Commodity housing-Commodity housing and others) | U1: Urban village, self-settlement, etc.-commodity housing | −0.007 |

| U2: Work-unit/reform housing-Commodity housing | 0.008 * | |

| Child in house×Mobility pattern (reference = L or D: Commodity housing-Commodity housing and others) | U1: Urban village, self-settlement, etc.-commodity housing | −0.019 |

| U2: Work-unit/reform housing-Commodity housing | 0.142 * | |

| Age×Migration direction (reference = Within-zone move) | Inward move | 0.002 |

| Outward move | −0.006 * | |

| Income×Migration direction (reference = Within-zone move) | Inward move | 0.016 ** |

| Outward move | −0.004 | |

| Education×Migration direction (reference = Within-zone move) | Inward move | 0.032 |

| Outward move | 0.016 ** | |

| Child in house×Migration direction (reference = Within-zone move) | Inward move | 0.065 * |

| Outward move | −0.156 * | |

| Age×Community stability | 0.001 *** | |

| Random effects | ||

| Var(_cons) | 0.020 | |

| Var(residual) | 0.612 | |

| Model fix statistics | ||

| 2 Log Likelihood | 3620 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, S.; Chen, J. Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Land 2021, 10, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070741

Mao S, Chen J. Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Land. 2021; 10(7):741. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070741

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Sanqin, and Jie Chen. 2021. "Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China" Land 10, no. 7: 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070741

APA StyleMao, S., & Chen, J. (2021). Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Land, 10(7), 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070741