1. Introduction

The notion of regionalism has resurfaced in the transitional China [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The state-orchestrated regional approach has been recognized as one of the most salient features in China’s “new urbanization” [

1,

5]. While the formations of city-region [

6] for urban agglomeration, urban unification (e.g., twin-city), metropolitanization, and urban clusters have enhanced regional competitiveness of China, the regionalization of economy did not effectively counter the fierce intercity competition, governance fragmentation, and rising regional inequalities [

1,

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. According to the report of the State Council in 2020, it is essential to promote the coordinated development of large, medium, and small cities to resolve regional imbalances. This requires new regional efforts of provincial and local governments to formulate strategies of cooperation and build regional institutions of intercity cooperation, coordination, and integration, instead of competition [

1].

The regional cooperation focusing on the theme of “city-helps-city” has emerged as a new type of spatial political economy in China and was actively promoted by the central government. In 2002, when President Xi worked as the governor in Zhejiang, the provincial government issued the Opinions on Implementing Mountain-Sea Project [

12] to address the problems of rising regional disparities, insufficient linkages, and uncoordinated development between developed coastal areas and the poor mountainous region within Zhejiang. Municipalities in Zhejiang were paired by the provincial government for interjurisdictional cooperation. In 2021, the regional cooperation of “city-helps-city” was upscaled [

13] to the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region to stimulate cooperation crossing provincial boundaries. To advance regional integration, cities in the developed provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Shanghai, have been mandated to aid less-developed cities in Anhui province.

The cooperation of “city-helps-city” represents different theoretical understandings of city-regionalism [

14,

15], regional governance [

1], and state rescaling [

16]. City-regionalism sees intercity cooperation as the response to the enhancement of global competitiveness. It is formed through state spatial selectivity or (regional) scale-building for the purpose of enhancing regional competitiveness [

17]. The famous notion of “new state space” [

16,

17] suggests the inevitable overconcentration of state resources (e.g., policies, authorities, funding, etc.) in large cities or city-regions and the consequent spatial divergence under this regional trend. Moreover, intercity cooperation is also regarded as the manifestation of “new regionalism” to engage different actors in a process of (regional) scale-building and solve the regulatory deficits in regional governance. Thus, cooperation is contingent upon the “distribution of politics” [

18,

19]. However, disadvantaged actors are often caught isolated or marginalized in these regional affairs, and a widened regional gap is assumed.

By contrast, the unique regional cooperation of “city-helps-city” represents the new norm of China’s regionalism. This type of cooperation is intrinsically associated with the redistributive regime of intergovernmental relations [

20,

21] and has been pursued for the coordination, integration, and regional equity rather than the competition under growth politics [

3,

4]. Different from the direct top–down spatial redistribution of higher-level government or the bottom–up collaboration based on local interests [

5,

22,

23,

24], “city-helps-city” is a mix of the vertical and horizontal regional governance approaches. State or provincial government promotes, orchestrates, and mandates the tasks of cooperation to ensure the legitimacy of this regional strategy [

1,

3]. The implementation still relies on local practices of interjurisdictional cooperation that might be geographically distant and not confined to the metropolitan areas among adjacent localities [

22]. Therefore, this type of cooperation cannot only remedy the crisis of previous spatial development, but also broaden the scope of regional cooperation. It resonates with Brenner [

17] and Wu [

1] on the periodization of regionalism that more spatially redistributive focuses are expected in the later stages of state spatial rescaling.

In this study, we focus on the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project in Zhejiang province, which is the national pilot region for “common prosperity” and the critical component of YRD integration. Our research question is to examine how regional cooperation of “city-helps-city” correlates with interjurisdictional linkages and reshapes city network structure of the region. We employed population flow to represent the interjurisdictional linkages of county pairs in Zhejiang to capture the regional centrality of localities. The flows of production factors such as labor, capital, information, and technology are considered as concomitants with population flow [

25] to reflect the functional correlations among cities [

26]. Our study assumes that regional cooperation of economic production, social affairs, and institutional arrangements under the Mountain-Sea projects are expected to enhance these linkages through various collaborative activities, especially for the backward places in the mountainous region of Zhejiang. To this end, we examine our hypothesis from three dimensions: the diversity of cooperation fields (scope), the intensity of different cooperation focuses (depth), and the legitimacy of cooperation.

Location-based big data [

27,

28] from China Mobile is employed to capture population flow in real-time. Our study comprehensively adopts methodologies of social network analysis, text semantic analysis, and regression models to identify the patterns of interjurisdictional linkages (dependent variables), the crucial information of Mountain-Sea cooperation (independent variables) and the correlations between these two. We propose the perspective of regional cooperation on “city-helps-city” to understand the intercity linkages that are not confined to geographic neighbors, especially for the less-developed areas. The aim is to contribute to the theoretical and empirical understanding of “city-helps-city” cooperation as the new spatial political economy in the transitional China and to provide implications on combating regional inequalities through intercity cooperation.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 puts forward a conceptual framework about the dimensions of the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project and possible mechanisms of the impacts on population flow.

Section 3 introduces the research area, data source, and analytical methodologies.

Section 4 demonstrates the spatial patterns of interjurisdictional population flow in Zhejiang, the Mountain-Sea Cooperation, and their correlations in the regression models.

Section 5 discusses relevant cases to elaborate the empirical results of regression models. The last section summarizes the paper and draws conclusions.

2. Conceptual Framework

During the past century, the processes of capitalist globalization have provoked distortions in the urban and regional development to exacerbate inequalities not only within the city but also at the intercity scale. Within the city, gentrification, economic segregation, and corporate controls, etc. [

29,

30], have brought about eviction to working-class people and undermined social injustice. For example, the transnational capitalist class (TCC) can control where people live, consume, and think through “icon projects”, thereby solidifying their own interests [

29]. Such inequalities are more pronounced in the “Alpha City”, such as London or New York City [

30,

31]. Moreover, the capitalist urbanization has promoted the winner-takes-all model that increased regional inequalities of winning and losing cities.

Therefore, it is crucial to address the increasing inequality under capitalist urbanization. Integrated planning should be prompted to engage a broader range of stakeholders representing the marginalized groups, facilitate capacity-building, and improve policy frameworks in the backward areas [

32]. The cooperation of different stakeholders on mega-events can also bring about positive social impacts on promoting skill training in disadvantaged people, enhancing social inclusion, etc. [

33]. Urban redevelopment, e.g., on brownfield infrastructure, needs to be cautious to the neoliberalism and its unequal and exclusionary impacts [

34].

As for the spatial dimension of inequalities, regional cooperation has been largely promoted. Regional cooperation refers to the type of development that occurs when two or more jurisdictions cross boundaries to form collaborations for short-term or long-term benefits in economic, ecological, or social fields [

35,

36]. Generally, existing studies have divided regional cooperation into three types: economic, social, and institutional [

10,

36,

37]. For example, Pan et al. explored the impacts of these three dimensions on urban land-use efficiency and indicated the potential mechanism behind them [

36]. Interjurisdictional cooperation is an effective way to promote coordinated economic development, joint construction, and sharing of public services and facilities, and finally realize balanced regional development.

The “city-helps-city” [

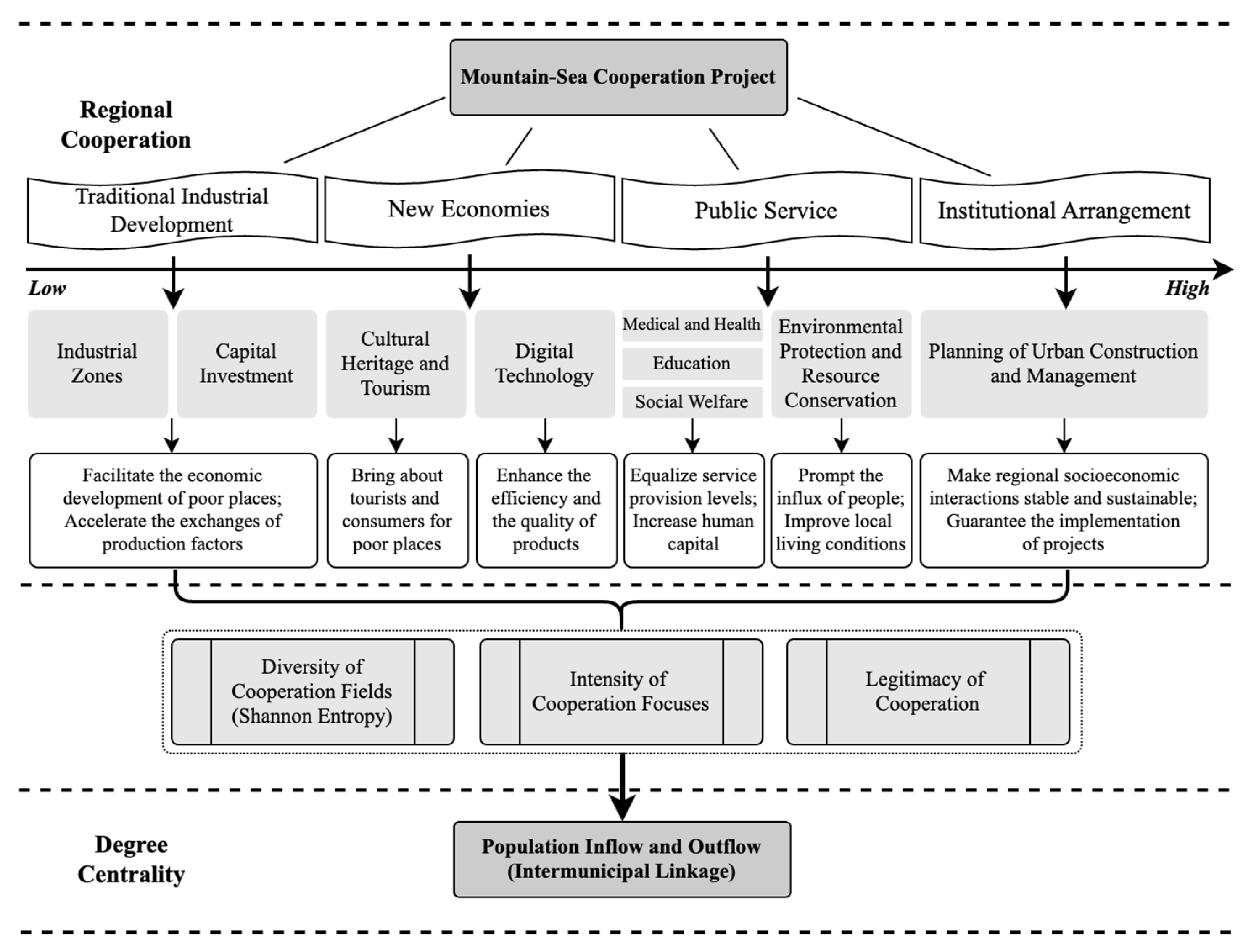

10], as an emerging mode of cooperation in China, vigorously bridges the regional gap and promotes the development of poorly developed cities under the assistance of their partners. Regional cooperation of the Mountain-Sea projects in Zhejiang can be conceptually separated into four dimensions of cooperation (see

Figure 1), including industrial development, new economies, social affairs of public services and environment, and institutional arrangements.

Industrial cooperation is the most common type of collaboration [

38,

39]. It involves fields of manufacturing, agriculture, and forestry, etc. The shortage of land quotas incentivizes the developed localities to collaborate with less-developed places that can adequately supply physical space for development [

36]. For example, developed and underdeveloped municipalities may jointly build industrial parks in underdeveloped regions, which can facilitate the economic development of disadvantaged places and accelerate the exchanges of production factors [

8,

9].

The cooperation on new economies is regarded as a more effective strategy. Less-developed counties can celebrate its endowed ecological and cultural resources. Transforming the value of the endowment into the value of development is one of the primary targets for interjurisdictional cooperation. This kind of cooperation brings about tourists and consumers to poor places, thereby stimulating ecological or cultural tourism and service industries. For example, the cooperation to organize mega-events can prominently brand the hosting city and promote its tourism and trade [

33]. Additionally, cooperation on digital technology is also common. For manufacturers, the efficiency and quality of products would be highly enhanced by intelligent manufacturing technology. Retails, especially for the agricultural products in impoverished and less connected areas, can also benefit. For instance, digital platforms of e-commerce are useful in advertising agricultural products of poverty counties through online streaming and fill the information gap between suppliers and demanders.

Social service is intimately related to the daily lives of people, especially on healthcare, education, and social welfare [

40]. The provisions of social services are dramatically uneven among counties with different capacities. Poor counties are more likely to suffer from the lack of social infrastructure, such as universities, research institutions, and healthcare facilities [

41,

42]. The collaboration on environmental protection and beautification are also pursued as complimentary tactics to prompt the influx of people and improve local living conditions. The cooperation on social services is expected to greatly equalize the levels of service provisions, increase human capital, and enable people in poor counties to have more opportunities in human development (e.g., jobs, education, health), thereby driving more population flow between developed and less-developed counties.

The institutional cooperation on spatial or regional planning enhances the stability and sustainability of socioeconomic interactions across regions [

43,

44]. Industrial and social cooperation is concomitant with regional or spatial planning of infrastructure construction (e.g., transportation planning) for people’s commuting across localities [

43,

45]. Institutionalized cooperation further legitimizes initiatives, programs, and proposals of collaboration, which can guarantee the implementation of projects. Under the guidance of planning, policy, or agreement, the patterns and measures of cooperation are clearly stipulated to support intercity connections and coordinated regional development [

1].

We establish a framework that proposes the insightful perspective of regional cooperation, especially the “city-helps-city” scheme, to understand the intercity population flow and the linkages of backward places in Zhejiang. Moreover, this study sheds light on how regional cooperation of Mountain-Sea project reshapes the structure of the city network by engaging less-developed localities in regional production networks and service together with institutional arrangements. This type of cooperation differs from the conventional cooperation types in that it not only goes beyond the collaboration between geographic neighbors, but also has been orchestrated by the central and provincial government to have institutional legitimacy. Therefore, we suppose that the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project has reconfigured the spatial structure of interjurisdictional networks in Zhejiang province and offers new insights on reducing spatial disparity in regional development.

4. Results

This study examines the correlation between the population flow (dependent variables) at county-level and key dimensions of interjurisdictional cooperation (independent variables) for the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project in Zhejiang. In

Section 4.1, we start with the descriptive analysis on dependent variables of county population inflows and outflows that are generated by social network analysis.

Section 4.2 further illustrates the features of independent variables of the intensity of different cooperation focuses, the diversity of cooperation fields, and the legitimacy of cooperation based on the text semantic analysis. Then,

Section 4.3 reports the results of our regression models to demonstrate whether and how the three dimensions of cooperation affect population flows between the poverty counties and other places under the Mountain-Sea Project. More interpretation on the results is given in this section as well.

4.1. Dependent Variables: The Population Flow of Municipalities (County-Level) in Zhejiang

Figure 3 shows the uneven patterns of interjurisdictional linkages of population flow (boldness of the lines) in Zhejiang province. Stronger interjurisdictional linkages mainly concentrate in four metropolitan areas: Hangzhou metropolitan area in the north, Ningbo metropolitan area in the northeast, Jinhua-Yiwu metropolitan area in the central region, and Wenzhou metropolitan area in the south. Central cities in these four metropolitan regions are core areas for population agglomeration and function as major engines of city-regional development. The red lines in

Figure 3 indicate that there are several subcenters that exhibit higher strengths of linkages to adjacent counties. Most of them are the hinterland of the metropolitan regions that enjoy the privileges of locations, such as “Changxing County–Wuxing District–Nanxun District”, “Linhai City–Jiaojiang District–Luqiao District–Wenling City”, “Cixi City–Yuyao City”, etc. The attractiveness of these functional nodes can be attributed to their comparative advantages in certain resource endowment and cultural heritage.

Although interjurisdictional linkages are not strong in the nonmetropolitan regions, there are still plenty of blue and yellow lines connecting mountainous counties to other municipalities. According to

Figure 4, this type of linkages overcomes the geographical limitations and mainly arises in the northwestern poverty region, e.g., Jiangshan City, Changshan County, and Kaihua County. Most of these lines bridge poverty counties with the provincial capital Hangzhou or some municipalities (e.g., Jiashan County) in Jiaxing that are next to Shanghai. By contrast, some poverty counties are more connected to their adjacent metropolitan cities (

Appendix A). For example, Cangnan County is well connected with its neighboring districts in the metropolitan city of Wenzhou. This pattern is also obvious for Jinhua-Yiwu metropolitan cities where short lines connect neighboring poverty counties (e.g., Wuyi County, Longyou County, and Yongkang County). Nevertheless, a large number of isolated poverty counties remain, which lack interactions with other municipalities. That is to say, these population flows are primarily intrajurisdictional within poverty counties. In this study, we expect the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project (

,

,

) to be correlated with interjurisdictional linkages between poverty counties and other municipalities (

.

4.2. Independent Variables: Mountain-Sea Cooperation in Zhejiang

We identified key information based on the news data from the website of the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project as our main explanatory variables. Through text semantic analysis, we grouped similar information and identified nine important cooperation fields (

Table 1). The focuses not only cover the economic cooperation in traditional fields but also embody collaborations on social affairs and institutional arrangements. The word counts for each cooperation field were calculated to represent the focuses of policies, programs, and projects under Mountain-Sea cooperation.

Word counts of the nine cooperation fields, shown in

Figure 5, representing the intensity of cooperation focuses, were used as our independent variables (

). The shares of each field are illustrated in

Figure 5 for the top 20 well-connected county pairs (interjurisdictional population flow). Pairs are arranged along the x-axis as their population flows decrease. The size of circles denotes the intensity of different cooperation focuses (

). It is assumed that higher intensity of cooperation fields is associated with more population inflow or less population outflow of poverty counties.

According to

Figure 5, the economic cooperation (black and gray circles) is often promoted through the co-building of industrial or agricultural parks, enclaves of industrial parks, retail and marketing, and capital investment. Economic cooperation, as the foundation for other types of collaborations, tends to be evenly distributed across county pairs. In addition, the pink and blue circles indicate that the cultural heritage and tourism together with digital technology account for a fair amount in the cooperation. This result suggests a common collaborative trend in new economy, the essential role of cultural heritage in tourism development, and the impacts of digital technology (e.g., digital platform) in promoting e-commerce in poverty counties.

Additionally,

Figure 5 also shows that cooperation on social affairs is one important component of the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project. Medical, educational, and social welfare services are at the top of

Figure 5, correlating with more population flow (top 20) and reinforced linkages of county pairs. However, cooperation on environmental governance is not strong in the displayed county pairs. The institutional cooperation, which is symbolized with yellow circles in the figure, is believed to offer the legitimacy through interjurisdictional agreement, regional or spatial plan, joint-issued policies, and forums of political leaders, etc., to ensure the implementation of projects.

Meanwhile, based on the news data from the official Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project website, we identified other model variables, as shown in

Table 1. Our models also include the diversity of cooperation fields (

), which is measured by Shannon entropy. The average diversity score for each county pair is 2.5 and a higher Shannon entropy value suggests that “city-helps-city” cooperation involves more fields. The diversity of cooperation may promote comprehensive development of poverty counties and avert population loss. The dummy variable of whether a county pair is mandated by the provincial government under the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project is used as the proxy for the legitimacy of interjurisdictional collaboration (

). The mandated county pair is expected to be more effective to conduct the mission, that is, to promote the development of poverty counties. We also control for the geographic (

) and economic (

) distance between counties in the cooperation pair. Greater distance is usually accompanied with higher cost of travel and communication that inhibits population flow, while the economic gap may drive people in poverty counties to flow into the developed places for better opportunities.

4.3. Model Results: The Impact of Mountain-Sea Cooperation on Population Flow in Zhejiang

Table 2 presents the cross-sectional regression model results on how the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project shapes the patterns of population outflow (from the poverty counties) and inflow (to the poverty counties). The interjurisdictional linkages of population are expected to be contingent upon the diversity of cooperation fields, different focuses of cooperation, and the legitimacy of cooperation. As for the geographical distance and economic gap between paired counties, they either facilitate or hinder the connections between localities. The purpose is to interrogate whether poverty counties can improve their positions in the regional network through cooperation with other municipalities, stimulated by the Mountain-Sea Project. The R-squared of Outflow and Inflow models is, respectively, 0.5986 and 0.6375, suggesting our models have relatively high goodness of fit.

According to

Table 2, the geographical distance (

) hinders the commuting between poverty counties in the mountainous area and other developed places, while the economic gap of county pair (

) accelerates both inflow and outflow of population. The diversity of cooperation fields (

), measured by Shannon entropy values, which is one of the primary explanatory variables, proved to be useful in restraining the outflow of population from impoverished counties. However, the expanding scope of cooperation fields does not work in bringing more inflow to poverty counties.

The interjurisdictional linkages of population flow also depend on policy focuses in cooperation fields (). As for the economic collaborations ) in traditional fields, according to the news data, joint construction on industrial zones and enclave industrial parks can speed the industrial development and create more jobs in poverty counties, thereby reducing the outflow of population. However, despite the increased economic opportunities in poverty counties, this type of economic collaboration has little effect on attracting people to these counties based on our model results. Capital investment ) that has been brought into poverty counties by Mountain-Sea cooperation is neither correlated with the outflow nor the inflow of population.

Our models further captured the cooperation on new types of economy, including cultural heritage and tourism and digital technology. The cooperation examples of the news data highlight that cooperation on cultural heritage and tourism

) fits the development of some poverty counties, where the legacies of culture and history provide privileged resources for tourism. This type of cooperation is effective to drive both population outflow and inflow, and it can comprehensively improve the interjurisdictional linkages of poverty counties according to the results in

Table 2. In addition, the news data also suggest that cooperation on digital technology

) is pursued for the purpose of facilitating connections between poverty counties and other places via digital platforms for retailing and investment, technical assistance for manufacturing, etc. However, our model results indicate that this variable is not significant in influencing population flow. This leads us to further consider whether the promotion of digital technology in poverty counties under the guide of the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project is working. These days, one significant phenomenon in China is that some residents (especially farmers) in backward areas have limited digital literacy and insufficient willingness to accept and take advantage of digital technology, which may diminish its effectiveness.

Moreover, the intermunicipal cooperation that goes beyond the economic affairs is found in our models to strongly promote the development of poverty places and increase their linkages with other parts of Zhejiang. Cooperation on educational (

) and medical

) services is expected to bring about more equitable provision of critical public services, which can promote human well-being in backward counties.

Table 2 indicates that cooperation on educational and medical services drives people in poverty counties to flow toward more-developed areas to seek for better opportunities. The cooperation examples in the news data illustrate how these cooperation programs contribute to the exchange of premium educational and medical resources (e.g., teachers, labor trainers, doctors, etc.) between poverty counties and the developed areas. Therefore, cooperation on educational and medical services empowers poverty counties with more human capital, which is equipped with competitive labor skills and improved health conditions. Additionally, our regression models display that cooperation on medical service is essential to driving a two-way linkage to have people commuting between county pairs. Nonetheless, collaborations on social welfare

) and environmental governance

) produce little effect on driving more population flow. These mixed results suggest that the focuses of current social cooperation between Mountain-Sea paired counties are limited to the educational and medical services, while cooperation in other fields have not yielded significant effects and should be given additional attention.

The institutional legitimacy of cooperation matters as well. Specifically, our models reveal that mandated cooperation () under the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project has positive effects on driving population flow and interjurisdictional linkages of poverty counties. Policy documents from the higher-level government endow cooperation with institutional legitimacy, to ensure that proposed initiatives are reasonable and the collaboration programs are effective. We also expect that intermunicipal agreement, regional or spatial planning, joint forums of political leaders, etc., ) can institutionalize the collaboration of county pairs to guarantee the legitimacy of projects and protect the benefits of poverty counties. However, it is not significant in our models. The fragmented institutional settings in China may undermine the implementation of regional or spatial plans, and the conflicts of interjurisdictional interests can also be detrimental to the linkages of counties.

6. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the regional cooperation of Mountain-Sea projects and how this “city-helps-city” scheme correlates with the interjurisdictional linkages (population flow) of poverty localities with other places in Zhejiang. Based on the location-based big data and the news data of Mountain-Sea cooperation, we are able to use social network analysis to measure interjurisdictional linkages between poverty counties and other places (dependent variable), and adopt text semantic analysis to identify the vital information of their collaborations (main explanatory variables) for our regression models.

The network structure of population flow is uneven in Zhejiang, that is, mainly concentrated in the four major metropolitan regions. However, the descriptive analysis of dependent variables shows that poverty counties in the mountainous regions also have connections with other municipalities of developed regions. These linkages are not confined to the geographic neighbors. The results of regression models further confirm that the linkages are associated with interjurisdictional cooperation that is stimulated by the Mountain-Sea projects. The diversity of cooperation fields, the intensity of different cooperation focuses, and the legitimacy of cooperation are found to have differentiated effects on the linkages of the backward counties with other developed places. Particularly, regional collaborations on cultural tourism and public services of education and health are essential to increasing the regional stances of poverty counties through the enhancement of their comparative advantages and human capital. Though we expect that the legitimacy matter for the effectiveness of cooperation, the institutional cooperation of spatial planning and regional agreement has not yielded significant impacts on stimulating more interjurisdictional population flow. Therefore, we suggest that regional cooperation, especially the “city-helps-city” projects, should take both the scope and depth of cooperation into account for future improvement and highlight the importance of institutional legitimacy-building, especially by the higher-level government to ensure the effectiveness of cooperation policies.

Emphasis on coordinated regional development is a prominent feature in the new urbanization of China. We see the rising importance of the state-orchestrated regional cooperation that focuses on “city-helps-city” for spatial redistribution and regional balance rather than simply fostering “new state space” for competitiveness. Our paper contributes to the empirical and theoretical understandings of this unique regional institution of “city-helps-city” in China. Through this study, we offer an important perspective of state-orchestrated regional cooperation to address spatial disparity and provide theoretical understanding on this spatial regime of “city-helps-city” cooperation. There are several policy implications that arise from the findings of our research.

First, the “city-helps-city” cooperation represents an attempt to combine the vertical and horizontal approaches in regional governance that can be learned by other countries and regions. It differs from the direct top–down spatial redistribution of higher-level government (the spatial Keynesianism) or the purely bottom–up collaboration based on local interests (the new regionalism). It is intrinsically redistributive for the coordination, integration, and regional equity, and often goes beyond the geographical adjacency. Within the context of capitalist globalization, we see the necessity for bridging the gap between global cities or metropolitan cities that are more favored by international capitals and the developing, declining, and backward places that are left behind in the intercity competition. Therefore, to involve stakeholders in less-developed areas, policymakers should develop the discourse and regime of development that consider space and emphasize the region. The spatial regime of “city-helps-city” cooperation represents this transformation and becomes an important reminder for other countries and regions when making policies to reduce regional inequality.

Second, when formulating regional cooperation policies, especially the “city-helps-city” projects, policymakers should give attention to legitimacy-building as well as scope and depth of cooperation. Our discussion highlights the significant role of higher-level government for promoting, orchestrating, and mandating cooperation to ensure the legitimacy of this regional strategy, thereby improving the scope and depth of cooperation. In this sense, the legal and regulatory system along with cooperation initiatives should be developed within a comprehensive realm of policymaking. The policy design needs to ensure the implementation of cooperation projects and provide guidelines of long-term evaluation on projects. For the developed municipalities, they should undertake more responsibilities in helping less-developed counterparts for more balanced regional development, particularly regarding improvement in education, healthcare, and technology development. On the other hand, backward places should be aware of their comparative advantages, e.g., cultural and natural resources, and strategically develop local industries and strengthen functions to complement other cities from a regional perspective. The collaborative localities should give full play to their comparative advantages for the effectiveness and the sustainability of interjurisdictional cooperation, thereby promoting more in-depth cooperation in broader fields.

Third, the “city-helps-city” cooperation aims to reach a “win-win” goal, rather than prompt one-way assistance from developed areas to poverty areas. Thus, it provides a new direction concerning co-benefits for future policy making. The formation of spatial regime on “city-helps-city” cooperation depends on the common interests of the poverty counties and the developed municipalities. Thus, it is crucial to provide incentives for both places and achieve the objectives of redistribution and development simultaneously. For example, in the economic cooperation of jointly building industrial parks, the developed municipalities can benefit from the sufficient land quotas provided by underdeveloped localities, and meanwhile, transferring industries and sharing revenues will promote the local conditions of poor places. This principle is universal and essential to fostering “city-helps-city” cooperation across various contexts. Different levels of government and multiple actors should collaborate on engaging less-developed localities in regional networks of production, service, and institutional arrangements, ensuring the legitimacy of cooperation and the realization of mutual benefits, and finally forming a more balanced and coordinated regional development.

There are some limitations in this study. First, for privacy concerns, the mobile phone signaling big data from China Mobile cannot show the social attributes of users in detail (such as their age, occupation, income level, etc.), so we are unable to conduct more in-depth analysis to explore the mechanisms of how intercity cooperation specifically drives population flows. Future research can analyze the cases of specific cooperation programs to reveal the mechanisms. Second, this paper takes the Mountain-Sea Cooperation Project in Zhejiang province as the case to examine whether the “city-helps-city” scheme of regional cooperation is correlated with the interjurisdictional linkages reflected by population flow, especially between the backward areas and other developed places. However, whether our conclusions and implications can be applied to other regions needs to be tested by taking various local contexts into account in future research. Third, this study only uses population flow to manifest the interjurisdictional linkages, while there are many types of urban networks that can represent the regional connections, such as the transportation network and the innovation network. Based on the analytical framework proposed in this study, we expect future works to explore the impacts of “city-helps-city” cooperation on other types of interjurisdictional networks and investigate their coupling degrees.