Climate Change Adaption between Governance and Government—Collaborative Arrangements in the City of Munich

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Climate Adaptation Entangled in Tensions between Different Modes of Governance

2. Conceptual Framework: Collaborative Arrangements

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Munich as Case Study

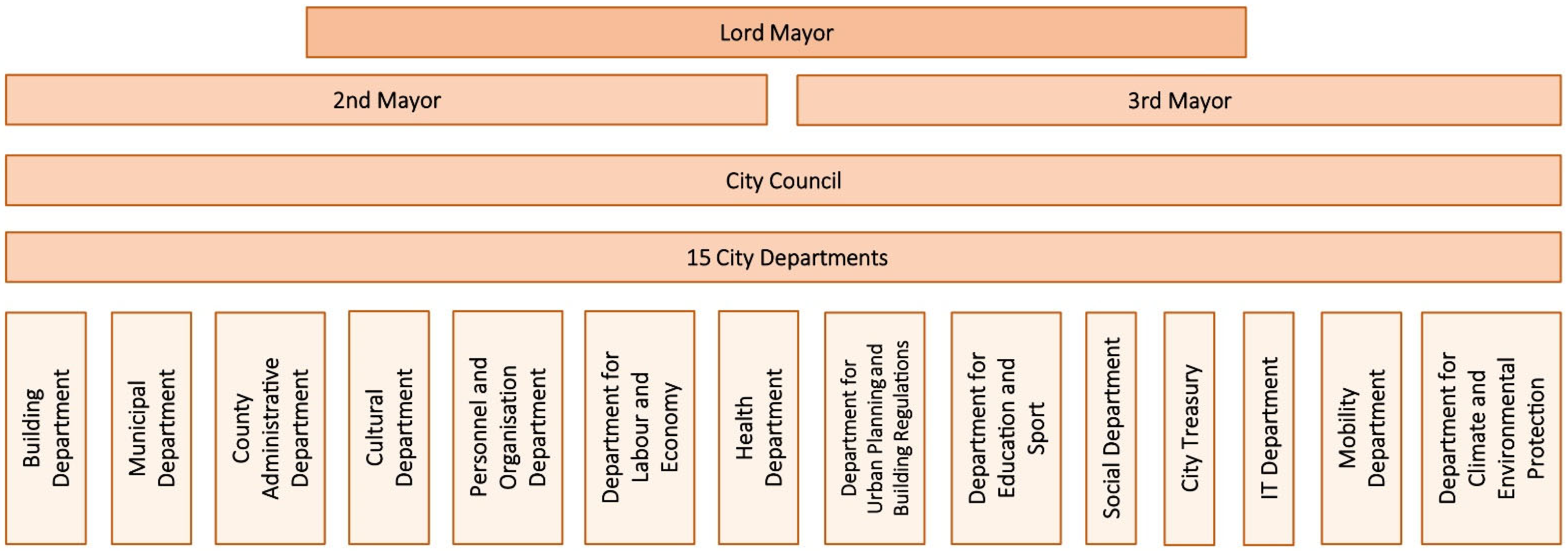

Munich’s Actors in the Context of CCA

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Semi-Structured Expert Interviews

3.2.2. Secondary Sources Analysis/Document Analysis

3.2.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Planning Arenas in the City of Munich: Actors and Conditions

4.2. Collaborative Arrangements in Horizontal and Vertical Structures: Relations, Positions and Power Distributions

4.2.1. Collaborative Arrangements within and between the City Departments (Planning Arena C)

Structures and Relations within the City Departments

“It would perhaps sometimes be preferable if decision-makers, real decision-makers, were […] not another four hierarchy levels above, because the person in charge is not a decision-maker, they still have to comply with a hierarchy. […] And that makes it very time-consuming.”

Structures and Relations between the City Departments

“And that is why we have chosen always to coordinate with the RGU at a very early stage. There is a joint paper on which cases require such an expert opinion and which cases do not. And that is actually going quite well now. So that was essential. […] Without them we would really have had a huge problem.”

4.2.2. Collaborative Arrangements within the City of Munich (Planning Arena B)

4.2.3. Collaborative Arrangements between the City of Munich and External Stakeholders (Planning Arena A)

Landowners and Investors (Include Project Developers)

Citizens

“Because it’s planning. It’s not just wishful thinking.”

“But, yes, I think that urban society has now reached a point where it is really difficult to communicate planning, changes, redensification.”

“The big problem, from my point of view, is that often only information is provided, or can be provided, but the citizens want to participate.”

5. Discussion

5.1. Collaborative Arrangements in Different Planning Arenas

5.2. “Silo-Thinking”, Communication Bottleneck, and Hierarchies as Barriers to CCA Mainstreaming in Collaborative Arrangements

5.3. Observed Strategies to Foster CCA Integration

5.4. Strategies, Solutions, and Recommendations for Urban Planning

5.5. Study Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- City departments: General Functions and Specific Responsibilities for CCA

| Relevant City Departments and Public Companies | Department Information and General Functions |

|---|---|

| Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations (PLAN) | 800 employees, main departments:

|

| former Department for Health and Environmental Protection (RGU) **, now Department for Climate and Environmental Protection (RKU) | 220 employees, main departments:

|

| Building Department | more than 4000 employees, main departments:

|

| Municipal Department | more than 2000 employees, main departments, and companies:

|

| Munich City Sewage (MSE) | more than 1000 employees, public company responsible for water protection, wastewater discharge and wastewater treatment |

- 2.

- Management structure of the City Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations

- 3.

- Main interviewees

| Munich Main Departments | Interviewees | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations (Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung) | 9 | Spatial development planning, traffic planning, urban planning, green planning, urban redevelopment, green expertise, planning permission |

| Department for Health and Environmental Protection (Referat für Gesundheit und Umweltschutz) | 2 | Urban climate, groundwater, climate adaptation; environmental protection in spatial planning |

| Building Department (Baureferat) | 1 | Horticulture |

| Municipal Department (Kommunalreferat) | 1 | Real Estate Service |

| Munich City Sewage (Münchner Stadtentwässerung) | 2 | Property drainage, overall drainage planning |

| Total | 15 |

- 4.

- Additional interviewees

| Experts Outside the Munich Administration | Interviewees | Background, Reason for the Questioning |

|---|---|---|

| University member | 2 | Institute for Urban and Regional Planning; Chair of Urban Water Management |

| Former city councillor | 1 | For insights into the collaboration between local politics and city administration from a political perspective |

| Employee in higher leadership level of another Bavarian city administration (smaller than Munich) | 1 | For comparison of hierarchical structures with smaller cities |

| Planner / Landscape architect | 1 | Owner of a planning office with experience in working with large cities (including Munich) |

| German Association of Cities and Municipalities | 1 | For insights into the legal background of administrative practices |

| Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (state level) | 1 | Focus on building, urban and spatial development |

| Bavarian State Ministry for the Environment and Consumer Protection (national level) | 1 | Focus on water management |

| Total | 8 |

- 5.

- Interview Guide

- 6.

- Articles and reports related to urban planning, CCA, land use conflicts, governmental and governance approaches in Munich:

- Ref. [56]

- Stadtentwicklungsplan München “Step 2040”, Online-Dialog “STEP2040” geht in die Verlängerung; available online: https://ru.muenchen.de/2022/69/Online-Dialoge-STEP2040-geht-in-die-Verlaengerung-100681 (accessed on 17 September 2022)

- 7.

- Urban planning and guiding principles

- Stadtentwicklungsplan München “Step 2040”; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/stadtentwicklung-perspektive-muenchen.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Munich district committee statutes (Bezirksausschuss-Satzung, Nr. 20) and open space design statutes (Gestaltungs- und BegrünungsS, Nr. 924); available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/rathaus/stadtrecht/alphabetisch.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Socially equitable land use (Sozialgerechte Bodennutzung, SoBoN); available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/sozialgerechte-bodennutzung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Wohnungspolitisches Handlungsprogramm “Wohnen in München VI” 2017–2021; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/wohnungsbaupolitik-stadt-muenchen.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- 8.

- Information about the Municipality

- City council resolutions; “Rats-Informations-System München”; available online: https://risi.muenchen.de/risi/sitzung/uebersicht;jsessionid=2541A04817E864AA57A31117CDC29786?0 (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Structure of the municipality and the single city departments; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/rathaus/verwaltung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Schedule and information of responsibilities of the whole municipality; https://stadt.muenchen.de/rathaus/verwaltung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Schedule and information of responsibilities of the City Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/portrait-referat-stadtplanung-bauordnung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

- Information about city-owned companies, especially Munich City Sewage; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/portrait-muenchner-stadtentwaesserung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Munich’s goals for Climate and environmental protection; available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/klimaschutz-nachhaltigkeit.html (accessed on 30 August 2022)

Note

| 1 | Research partner: Technical University of Munich (TUM) with the Chair of Strategic Landscape Planning and Management (Coordination) and the Institute of Energy Efficient and Sustainable Design and Building; the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich (LMU) with the Department of Sociology, and the Institute for Ecological Economy Research (IÖW) in Berlin. |

References

- IPCC. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haaland, C.; van den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zölch, T.; Wamsler, C.; Pauleit, S. Integrating the ecosystem-based approach into municipal climate adaptation strategies: The case of Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. (Eds.) Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions: Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, W.; Lenzholzer, S.; van den Brink, A. Developing green infrastructure design guidelines for urban climate adaptation. J. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 12, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Rieke, H.; Rall, E.; Rolf, W. Routledge Handbooks: The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology; Douglas, I., Anderson, P.M.L., Goode, D., Houck, M.C., Maddox, D., Nagendra, H., Tan, P.Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, M.; Favargiotti, S.; van Lierop, M.; Giovannini, L.; Zonato, A. Verona Adapt. Modelling as a Planning Instrument: Applying a Climate-Responsive Approach in Verona, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, D.L.; Nita, A.; Iojă, C.I.; Niţă, M.R. Disentangling the connections: A network analysis of approaches to urban green infrastructure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E. Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erlwein, S.; Pauleit, S. Trade-Offs between Urban Green Space and Densification: Balancing Outdoor Thermal Comfort, Mobility, and Housing Demand. UP 2021, 6, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lierop, M.; Betta, A.; Meyfroit, A. LOS_DAMA! Synthesis Report; Alpine Space: München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gailing, L. RaumFragen: Stadt—Region—Landschaft: Handbuch Landschaft; Kühne, O., Weber, F., Berr, K., Jenal, C., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; Turnheim, B. The Great Reconfiguration: A Socio-Technical Analysis of Low-Carbon Transitions in UK Electricity, Heat, and Mobility Systems: A Socio-Technical Analysis of Low-Carbon Transitions in UK Electricity, Heat, and Mobility Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstad, H.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J.; Vedeld, T. Designing and leading collaborative urban climate governance: Comparative experiences of co-creation from Copenhagen and Oslo. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation: Transformation toward sustainability in urban governance and planning. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Hüesker, F.; Albert, C.; Brillinger, M.; Huang, J.; Lupp, G.; Scheuer, S.; Schlätel, M.; Schröter, B. Governance models for nature-based solutions: Seventeen cases from Germany. Ambio 2021, 50, 1610–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. Understanding Governance: Ten Years On. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1243–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerink, J.; Kempenaar, A.; van Lierop, M.; Groot, S.; van der Valk, A.; van den Brink, A. The participating government: Shifting boundaries in collaborative spatial planning of urban regions. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2017, 35, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J. Governing as Governance; SAGE: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berr, K.; Jenal, C.; Weber, F.; Kühne, O. Landschaftsgovernance: Ein Überblick zu Theorie und Praxis; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose-Oji, B.; Buijs, A.; Gerőházi, E.; Mattijssen, T.; Száraz, L.; Van der Jagt, A.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.; Andersson, E.; Kronenberg, J.; et al. Innovative Governance for Urban Green Infrastructure:A Guide for Practitioners: GREEN SURGE Project Deliverable 6.3; University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, P.P.J.; Dieperink, C.; Laerhoven, F.; Runhaar, H.A.C.; Vermeulen, W.J.V. Towards a Conceptual Framework for The Study of Shifts in Modes of Environmental Governance - Experiences From The Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wild, T.; Freitas, T.; Vandewoestijne, S. Nature-Based Solutions: State of the Art in EU-Funded Projects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C.; Wickenberg, B.; Hanson, H.; Olsson, J.A.; Stålhammar, S.; Björn, H.; Falck, H.; Gerell, D.; Oskarsson, T.; Simonsson, E.; et al. Environmental and climate policy integration: Targeted strategies for overcoming barriers to nature-based solutions and climate change adaptation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.; Elands, B.; Havik, G.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Gerőházi, E.; van der Jagt, A.; Mattijssen, T.; Møller, M.S.; Vierikko, K. Innovative Governance of Urban Green Spaces. Learning from 18 Innovative Exampls across Europe: EU FP7 Project GREEN SURGE, Deliverable 6.2. ENV.2013.6.2-5-603567; 2013–2017. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293825383_Innovative_Governance_of_Urban_Green_Spaces_-_Learning_from_18_innovative_examples_across_Europe (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Buijs, A.; Hansen, R.; van der Jagt, S.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Elands, B.; Rall, E.L.; Mattijssen, T.; Pauleit, S.; Runhaar, H.; Olafsson, A.S.; et al. Mosaic governance for urban green infrastructure: Upscaling active citizenship from a local government perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, G. The Implementation of Green Infrastructure: Relating a General Concept to Context and Site. Sustainability 2017, 9, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gethmann, C.F. Partizipation als Modus sozialer Selbstorganisation?: Einige kritische Fragen: Reaktion auf H. Heinrichs. 2005. Partizipationsforschung und nachhaltige Entwicklung. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2005, 14, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Policy Network Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S.J. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wickenberg, B.; McCormick, K.; Olsson, J.A. Advancing the implementation of nature-based solutions in cities: A review of frameworks. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 125, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpfert, C.; Wamsler, C.; Lang, W. Institutionalizing climate change mitigation and adaptation through city advisory committees: Lessons learned and policy futures. City Environ. Interact. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Healey, P. ‘My Voice: My Place’: Tracking Transformations in Urban Governance. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempenaar, A.; Brinkhuijsen, M.; van den Brink, A. The impact of regional designing: New perspectives for the Maastricht/Heerlen, Hasselt/Genk, Aachen and Liège (MHAL) Region. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2017, 46, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Healey, P. Transforming governance: Challenges of institutional adaptation and a new politics of space1. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Luque-Ayala, A.; McFarlane, C.; MacLeod, G. Enhancing urban autonomy: Towards a new political project for cities. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Treib, O.; Bähr, H.; Falkner, G. Modes of governance: Towards a conceptual clarification. J. Eur. Public Policy 2007, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Applied Social Research Methods, Vol. 5: Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA. USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Alle Politisch Selbständigen Gemeinden mit Ausgewählten Merkmalen am 30.09.2022 (3 Quartal 2022). 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Laender-Regionen/Regionales/Gemeindeverzeichnis/Administrativ/Archiv/GVAuszugQ/AuszugGV3QAktuell.html (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Statistische Daten zur Münchner Bevölkerung. 2022. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/statistik-bevoelkerung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Bevölkerungsprognosen des Referats für Stadtplanung. 2021. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/bevoelkerungsprognose.html (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Mühlbacher, G.; Koßmann, M.; Sedlmaier, K.; Winderlich, K. Stadtklimatische Untersuchungen der sommerlichen Temperaturverhältnisse und des Tagesgangs des Regionalwindes (“Alpines Pumpen”) in München. Berichte des Deutschen Wetterdienstes. Available online: https://www.dwd.de/DE/leistungen/pbfb_verlag_berichte/pdf_einzelbaende/252_pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Konzept zur Anpassung an die Folgen des Klimawandels in der Landeshauptstadt München; Landeshauptstadt München: München, Germany; Augsburg, Germany; Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Landeshauptstadt München. Monitoring zur Maßnahmenumsetzung des “Maßnahmenkonzept Anpassung an den Klimawandel in der Landeshauptstadt München”. 2021. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/dam/jcr:31f7eb1f-e463-428f-975a-49b599e1dbc7/Monitoringbericht_Klimaanpassungskonzept.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Freiflächengestaltungssatzung. 1996. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/dam/jcr:b4f79ad9-8e04-4710-ae27-ce56b00c7bbe/Freiflaechengestaltungssatzung_210313.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Neues SoBoN-Baukastenmodell für mehr bezahlbare Wohnungen. Rath. Umsch. 2021, 142, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Landeshauptstadt München. Wohnungspolitisches Handlungsprogramm: “Wohnen in München VI” 2017–2021; Landeshauptstadt München Eigenverlag: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Landeshauptstadt München. Stadtverwaltung. 2021. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/rathaus/verwaltung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Flick, U. Triangulation: Eine Einfhrung; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Green City e.V. Unsere Politische Arbeit. Einflussnahme für mehr Umweltschutz vor Ort. Available online: https://www.greencity.de/politische-arbeit/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Klimaneutrales München 2035—Ein Fahrplan für die Stadtplanung. 2021. Available online: https://ru.muenchen.de/2021/192/Klimaneutrales-Muenchen-2035-ein-Fahrplan-fuer-die-Stadtplanung-98155 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Landeshauptstadt München. Stadtentwicklungsplan 2040—Entwurf. 2022. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/stadtentwicklungsplan-2040.html (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Reiß-Schmidt, S. Das Wachstumsdilemma: Stadt weiterbauen, aber wie?: Fallstudie München. Pnd Rethink. Plan. 2021, 1, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsen, T. Negotiations Between Developers and Planning Authorities in Urban Development Projects. Disp-Plan. Rev. 2020, 56, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J.W.; Geels, F.W.; Loorbach, D. Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions: Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brasche, J. Kommunale Klimapolitik: Handlungsspielräume in Komplexen Strukturen; Technische Universität: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Landeshauptstadt München. Über das Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung. 2021. Available online: https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/portrait-referat-stadtplanung-bauordnung.html (accessed on 30 August 2022).

| Collaborative Arrangement [31] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Attributes | Definitions | Sources |

| direction of arrangement | the direction can be hierarchical (vertical), or horizontal, as well as internal and external | [38] |

| actor role and structure of arrangement | positions and roles (e.g., leading, following) taken by actors and differences between them (e.g., equal) in the collaborative arrangements | [23,31,35,39] |

| function of arrangement | main functions of the collaborative arrangements | [31] |

| locus of authority | the position and structure of decision making | [39] |

| level of interaction | the level and frequency of interaction within and across the different planning arenas. | [31] |

| mutuality | the interdependence of different planning arenas on each other in the collaborative arrangements through shared commitment, internal legitimacy, mutual understanding, and trust. | [31] |

| Categories | Description |

|---|---|

| type of actors | actors involved in the urban planning process, types of actors, knowledge and expertise |

| conditions | motivation, discourse, knowledge, and expertise |

| responsibilities, structure, and function | tasks in the process, professional (thematic) responsibility, decision making power |

| collaborative arrangements | structure and direction of arrangements (either horizontal or vertical), collaboration within the municipality, horizontal dependencies, collaboration with external actors, internal arrangements and structures of arrangement, interaction format, function of arrangement |

| hierarchical structures | vertical structures between actors within the municipality and the local politicians |

| relationships (mutuality) | level of interaction/collaboration, dependencies, interpersonal relations, commitment, mutual understanding, assessment/evaluation of collaboration |

| barriers | as reported by actors regarding collaboration and governance structures |

| strategies/solutions | as reported by actors regarding collaboration and governance structures |

| Barriers from the Administrative Point of View | Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| thinking and acting in “silos“ | “Yes, in principle, it would always be desirable to see ourselves more as a city and less as a department.” |

| lack of collaboration | “That’s exactly the problem, that we give an opinion and then basically the issue is taken up without our involvement and we are simply confronted with the final outcome.” “And then we find out, whoops, it was approved in a completely different way or the building development has expanded or for some other reason it is no longer possible […] These are the issues where we realise that our concerns are still being neglected, yes.” |

| lack of transparency | “Yes, as a rule, when a development plan is drawn up, we are listened to, and can also give our opinion. However, our experience is that it sometimes is adopted, sometimes dropped, for whatever reason.” |

| interpersonal aspects | “However, perhaps got a bit overlooked with the change of staff […]. Maybe we can push that again.” “Perhaps it was also because I couldn’t work with person […] at all.” |

| Barriers from the Administrative Point of View | Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| long decision-making processes | “When you talk to small municipalities that have exactly the same funding programmes, you sometimes wish you had a mayor who would say, ‘Let’s do it now.’ Then the matter would be decided in seven minutes. By the time I get through all the committees, seventy days have been lost.” |

| lack of exchange | “I think it would be really helpful to have more exchange with local politicians in order to discuss the individual issues and not only the formal levels of the committees.” |

| lack of trust | “And if you look at many discussions, they are always socially, politically very emotional and not always rational. So the administration’s proposal may not be adopted.” (By the local politicians—authors’ note)” “What we would really like to see more often is that our professionalism is recognised by politicians. It really is the case that we are in the wonderful position in the state capital of Munich of being able to afford really good professionals, but we often feel that it is absolutely necessary to seekexternal consultation, which is also completely legitimate.” |

| lack of resources | “However, to change or adjust old development plans, which would be legally possible and would also make sense in many cases, seems to fail not only because of the duration, but also because of the capacity, because it also raises costs.” |

| Barriers from the Administrative Point of View | Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| many different actors with different requirements, e.g., residential property owners’ association (WEG) | You should never start with a residential property owners’ association, because someone is always against it.” “What’s really bad is that I have to deal with a WEG, which means almost nothing works.” |

| lack of trust and transparency | “In about 10% of building applications, lawyers also involved from the developer’s side right from the start.” “There are also cases where things are promised in the consultation process but are not included in the submitted building application.” |

| profit orientation | “People want more than they are legally entitled to, for example in terms of building law, or they want to avoid expenses.” “In the guise of technical issues, as a building permit authority, we also basically have to manage two original sins: greed and avarice.” “And of course, the investor is primarily interested in earning money. And I would say that the common good and making money can sometimes go together, but in my experience, it is usually not the case.” |

| long decision-making processes | “It would perhaps sometimes be more favourable if decision-makers, real decision-makers, were […] not another four hierarchy levels above, because the person in charge is not a decision-maker, they still have to comply with a hierarchy. […] And that makes it very time-consuming.” |

| lack of willingness to experiment | “So especially with new legal regulations, it is of course always possible that someone tries it on. And then someone sues. Someone always sues in Munich. We have many lawsuits, hundreds every year.” |

| lack of possibilities to influence due to legal provisions | “If something is legal, no matter how […] morally or even technically out of date, if it does not violate a building code regulation, it has to be approved.” |

| lack of acceptance of binding planning instruments | “Our experience teaches us that people do not like to be forced into things and will always resist.” |

| bias and negative public image of the administration | “Because it is often the case that there are still certain opinions among the population that we in the administration simply stick to the rulebook regardless.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Linke, S.; Erlwein, S.; van Lierop, M.; Fakirova, E.; Pauleit, S.; Lang, W. Climate Change Adaption between Governance and Government—Collaborative Arrangements in the City of Munich. Land 2022, 11, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101818

Linke S, Erlwein S, van Lierop M, Fakirova E, Pauleit S, Lang W. Climate Change Adaption between Governance and Government—Collaborative Arrangements in the City of Munich. Land. 2022; 11(10):1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101818

Chicago/Turabian StyleLinke, Simone, Sabrina Erlwein, Martina van Lierop, Elizaveta Fakirova, Stephan Pauleit, and Werner Lang. 2022. "Climate Change Adaption between Governance and Government—Collaborative Arrangements in the City of Munich" Land 11, no. 10: 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101818

APA StyleLinke, S., Erlwein, S., van Lierop, M., Fakirova, E., Pauleit, S., & Lang, W. (2022). Climate Change Adaption between Governance and Government—Collaborative Arrangements in the City of Munich. Land, 11(10), 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101818