Abstract

Globally, indigenous knowledge (IK) has been shown to be a critical factor in economic growth and sustainable development and is as important as scientific knowledge. However, when it comes to the African narrative, IK research still seems to fall short, even with the great recognition and interest it is attracting. IK has always been underprivileged and marginalized, treated as an unsubstantiated type of knowledge that cannot provide any scientific solutions. Consequently, the aim of this paper is to provide an insight into the importance of IK research from a comparative African perspective from 1990 to 2020. The paper used a combination of bibliometric analysis and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol to provide a comprehensive view of IK research. The VOSviewer software was used to provide a visualization of the bibliometric analysis through network maps. The findings suggest that while IK is a globally recognized concept, the African narrative is missing and not told by Africans. Most researched studies on IK in Africa are on ethnobotany, customs, traditions, agroforestry, and agriculture. Moreover, most of the IK research is from Southern Africa. There is a need for the integration of IK and scientific knowledge to develop well-informed approaches, methodologies, and frameworks that cater to indigenous communities and resilient ecological development. The research outcomes provide valuable insights for future research trends; they further highlight opportunities for building research partnerships for strengthening policy generation and implementation.

1. Introduction

Indigenous people are estimated to number around 476 million globally and make up only six percent of the global population [1]. They are known as the “first” or “original” people connected to nature through history and cultural bonds [2] The importance of Indigenous people and their knowledge systems was first recognized in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in their report on sustainable development [3]. For centuries, IK has been sidelined by Western knowledge, where it has been deemed as having no scientific value by Western institutions [4], and the African continent is no exception [5]. Yet, throughout the years, IK has managed to withstand and survive the test of time by adapting different ways that lead to sustainable livelihoods [2,6,7]. Indigenous people understand local ecosystems, they live in areas with high biodiversity values [8], have close interaction with nature, and rely on animal and plant behavior [9]. Indigenous communities possess knowledge regarding biodiversity changes, and such knowledge is produced from generation to generation and transmitted through oral history [10].

Regardless of the rapidly increasing human population, there is a need to understand the importance of nature’s ecological patterns, ways, and changes [11]. Most indigenous people are in remote areas, making them better able than scientists to provide insight into local biodiversity problems and solutions [8]. Furthermore, IK provides various perspectives on the interrelationships between the environment and humans and their social and biophysical surroundings [12,13]. Indigenous perspectives on the importance of nature’s contribution to people have gained traction over the years [14,15]. These practices and processes provide a lens through which nature’s contribution to people can be identified and linked [16,17]. The rapid attraction and acknowledgment of IK have warranted it to be recognized as another form of science used to explain the ecological and socio-cultural realities of diverse African societies [18]. Although there is increasing attention on IK in Africa due to the acknowledgment of IK by the IPBES, most publications are slow in coming and most publications are mainly from South Africa [19]. Most African IK publications are on ethnobotany, culture, traditions, language, wisdom, and wildlife [20,21].

To promote African sustainability in current land use, natural resource administration, and maintenance initiatives, it is essential to recognize indigenous people, their knowledge, and ethics [22]. IK presents sustainable practices and solutions to current global climate change and food and water scarcity [23]. Research practitioners and specialists can increase community buy-in by incorporating local knowledge practices within their projects, which will facilitate better chances of success [24]. Consequently, there is a need to provide the IK linkages with ecosystem services and human wellbeing from an African perspective for sustainable livelihoods and resilient communities [25]. Predominately within Western-oriented academia and research, African voices tend to be marginalized or suppressed because indigenous knowledge and methods are often ignored or not considered [26]. Similarly, this study aims to provide a comprehensive bibliometric analysis using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method on the scientific literature of IK linkages from an African perspective over the past three decades. The paper is structured as follows; the conceptual background is presented next, followed by the materials and methods used in the study, the results, and, lastly, the discussion, coupled with concluding remarks, is presented.

Conceptual Background

Indigenous knowledge has various names such as traditional knowledge, rural knowledge or folk knowledge [27], ethnosciences [28], indigenous technical knowledge, and local knowledge, and it is produced by a certain culture and passed on from generation to generation [29]. For this paper, we will use the term indigenous knowledge (IK). IK is unique to a particular society that has survived through the years [30] and forms the basis of the native decision-making process in health, agriculture, spiritual education, and ecological management [31]. IK consists of traditional local, non-scientific beliefs, customs, and methods that are normally described as informal forms of knowledge [32]. The strengths of IK include—but are not limited to—legitimacy, credibility, prominence, and usability [33,34]. Furthermore, IK denotes what indigenous people have known and done for generations [35], through evolved practices that are suitable for coping with change [36]. In various instances, IK is orally transmitted from generation to generation, and it is articulated and lives through songs, stories, and art on rocks and caves and even through traditional laws [29]. IK has withstood the test of time and has been the pillar of rural communities, their livelihoods, and environmental conservation for decades [37].

For the protection and conservation of the environment, there is a need to recognize IK [29] and the importance it plays in environmental management and adaptation [5]. Colonialism plays a key role in the disappearance of knowledge, practices, and systems in Third World countries. Western scientific knowledge has suppressed indigenous cultural belief systems, practices, and taboos of native communities [29]. What indigenous communities know and do, the knowledge they pass on from generation to generation, and the practices that have stood the test of time and proven to be sustainable to cope with change are known as indigenous knowledge [4]. Indigenous communities develop a certain set of skills, practices, and philosophies from their local perspective, which is referred to as local knowledge systems [38]. Such local knowledge systems inform decision-making regarding important traits of day-to-day living [39].

IK has sustained indigenous communities for decades [40], it is generationally inherited through culture, rituals and custom practices, codes of conduct, and storytelling [41], it represents people’s customs, beliefs, and observations which are unique to a certain society [27]. Indigenous communities use the knowledge for environmental management and socioeconomic and philosophical practices because it is precise and straightforward [42]. IK is often referred to as a system due to its holistic nature that connects and responds to all aspects of reality together with nature. It embodies ethical values, the principles of accountability, transmission, and a system of rules and practices [41] (p. 2). The organization of IK is functional, situated within the broader context of cultural traditions [43]. IK is an integral part of Africa’s heritage, dating back to pre-colonial times when it was used to address various survival challenges [37]. Moreover, IK is based on practice, used by local communities to predict situations [27] and is site-specific at the village level [44]. IK reflects numerous layers of existence and methods of representation and understanding; it encompasses various areas of knowledge such as astronomy, climate change, environmental management, political, socioeconomic, entertainment, leadership, community values, and literature [40]. The knowledge resource within each indigenous society has a history behind it that guides the process of development [4].

The importance of IK for the sustainable use and management of ecosystem services, biodiversity, and human well-being is of interest in the academic field of social sciences and environmental management [45,46]. Still, the importance of knowledge and skills inherent in the relationship between humans and nature has not yet been emphasized. Moreover, when it comes to managing the natural system through the protection of people’s languages, customs, and traditions, indigenous and local contributions are least recognized [47]. Humans value the benefits of nature for their relationships, knowledge, and understanding [48]. Given the significance of connecting indigenous peoples and local communities to nature around the world, there is a need to better appreciate and articulate the implicit mutuality between people and their ecosystems to manage and use resources to survive and thrive [49]. Over the years, both MA and IPEBS have developed frameworks that describe people–nature relationships. These frameworks explicitly link nature with human well-being, clearly delineating how well-being is derived from nature [50,51]. One of the IPBES’s eleven operating principles is to respect and supply recognition to the contributions of IK to the preservation and sustainable use of nature and ecosystems [52].

This engagement has led to global recognition, wherein the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (IPLC) grants the right to participate in decision-making processes that affect livelihoods, customs, and traditions [53]. The connections of indigenous and local peoples with nature are not limited only to the benefits or services that people derive from ecosystems, as recognized in international frameworks, but also include the knowledge and skills of people that enable people to take advantage of these benefits [54,55]. Moreover, IK gives excellent relevance to discernments for controlling deforestation, understanding climate change behavior, sustaining food security, reducing carbon dioxide emissions, and restoring resilient landscapes [53].

Various studies have shown that human interaction with the natural environment has been associated with improved health outcomes, “particularly” within indigenous communities [56]. Furthermore, studies have proven that focusing on the social and cultural determinants of health and considering a holistic view of well-being can help better understand health inequities [57]. Spending more time in natural settings has been demonstrated to boost social engagement and lower stress, and this is evident with indigenous people and communities, as they engage with the natural environment daily [58,59,60]. Views of well-being and prosperity are important for the more extensive class of indigenous perspectives. For some, indigenous wellbeing is carried out through connections of the shared care of family and non-human affiliations that are encoded inside a scene and continue on through oral stories [61]. Indigenous communities use their knowledge for decision-making pertaining to food security, education, natural resource management, land distribution, climate adaptation, and human and animal health [40]. This provides a clear indication that IK has a potential role to play when incorporated into a contemporary landscape, conservation and adaptation research, and practice [3].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Extraction

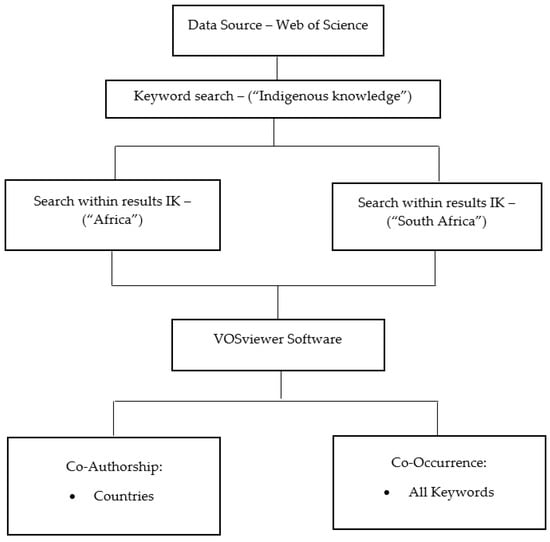

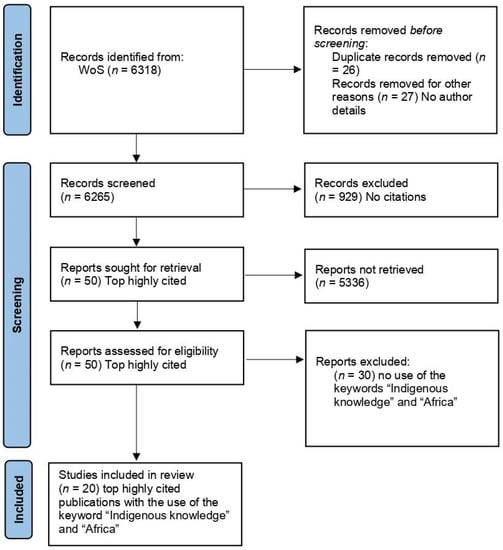

Web of Science (WoS), owned by Clarivate, was chosen and used as the preferred database for this study due to its high reliability and inclusivity of data, and its extensive collection of methodical tasks across distinct information domains and a dataset for large-scale data-intensive studies [62]. Only publications published from 1990 to 2020 were chosen because indigenous knowledge in developing countries was gradually recognized during this period, and the United Nations (UN) established the Working Group on Indigenous Peoples, which declared indigenous rights as mandatory for the future of sustainable development [63]. Data were searched and retrieved on 23 March 2022 from WoS via the University of Johannesburg Library database website. The first main search was the keyword “Indigenous Knowledge”, which yielded 4743 documents. We then proceeded to add the keyword “Africa” within the main search results, which yielded 947 documents, and lastly, we added the last keyword “South Africa” within the main results, yielding 628 documents. In total, all search results resulted in 6318 documents (Figure 1). The search query explored titles, abstracts, keywords, citations, authors, affiliations, publications, and journals. The search data was saved and exported into a plain text document and imported into the VOSviewer software for the analysis and visualization of the results. Ten highly cited publications from the global and African perspectives were selected and included within the study for a full-text reading to produce a comprehensive contextual review of IK (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the systematic bibliometric review.

Figure 2.

Systematic review process flow diagram of the selection process of publications for WoS, based on PRISMA.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis and PRISMA Method

This paper combines bibliometric analysis, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol, and a traditional review based on full-text reading to produce comprehensive results for the study. Bibliometric analysis methods are used to identify publication trends, such as journal types, research types, leading research organizations, countries, citation patterns, and keywords and titles [64]. Bibliometric analysis can be defined as a study where research work is described in the scientific literature and evaluated using various indicators [65]. Bibliometric analysis was chosen because it allows the researcher to track emerging or hot topics for study and allows them to access updated research insights [66]. PRISMA states that a systematic review is an explicit way to identify, select, and critically evaluate relevant research, and to collect and analyze data from studies included in the evaluation [67]. PRISMA is a protocol to conduct systematic reviews consisting of a four-phase flow diagram (see Figure 2) and a 27-item checklist serving as a guide for authors [68,69]. We chose PRISMA due to the recognition it has based on its comprehensiveness, the fact that it is used by various disciplines, and that it provides the potential to increase reliability across reviews.

Previous research studies conducted on IK using bibliometrics identified various research directions and future trends for IK, particularly in Africa. For instance, Maluleka and Ngulube [70], used bibliometric analysis to indicate the publication patterns of indigenous knowledge in Africa. Their results indicate that the bulk of IK research was conducted in the medicinal and pharmaceutical sciences. Kwanya and Kiplang [71], conducted a bibliometric analysis on indigenous knowledge research in Kenya, and their results discovered that minimal research was done on IK in Kenya and that most research conducted on IK in Kenya was conducted by non-Kenyan researchers. Previous studies conducted using the PRISMA protocol on IK have provided valuable insight into IK and its significance within the body of knowledge. For example, Hitomi and Loring [72] conducted a systematic review of gender, age, and other influences on local and traditional knowledge research in the north. Their findings suggest that there is an ostensible predisposition towards male knowledge-holders, typically hunters and elders, over women and youth. Meanwhile, Mbah et al. [73] conducted a systematic review of the deployment of IK systems toward climate change adaptation in developing world contexts, focusing on implications for climate change education. Their results indicate that IK systems are contributory to climate change adaptation, particularly in African and Asian Indigenous communities.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Distribution of Publications

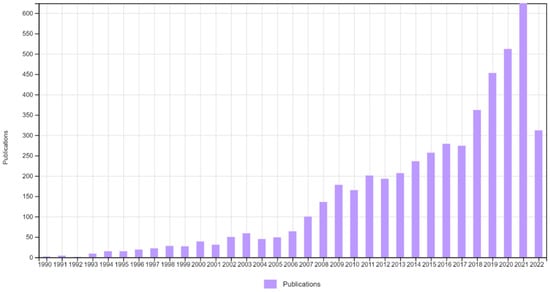

Figure 3 presents the number of related papers published from 1990 to 2020. The results show that few papers on the researched topics were published before 2006, while there is a rapid increase from 2009. The significance of IK started being recognized in 1980 by influential international institutions such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). At the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, indigenous rights were recognized to be important for our ecological future [63]. International acknowledgment and backing for IK intensified over the 1990s. Since 2009, the concept of IK has been popular and has shown increasing growth in publications, and in 2015, indigenous people were one of the major groups involved in consultations and discussions towards implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The year 2020 recorded the highest number of publications on IK and its practices; this is due to the recognition given to IK in addressing climate change from the perspective of local communities. This has been shown to promote sustainable ES/environmental management [7]. The increase in publications on IK has been in response to the rapid global degradation and deterioration of ecosystem services and biodiversity, which pose a threat to human well-being globally [62,63].

Figure 3.

The number of related papers published on indigenous knowledge from 1990 to 2020.

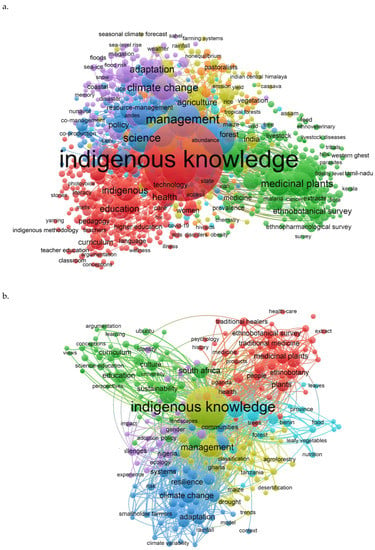

3.2. Co-Occurrence of Keywords

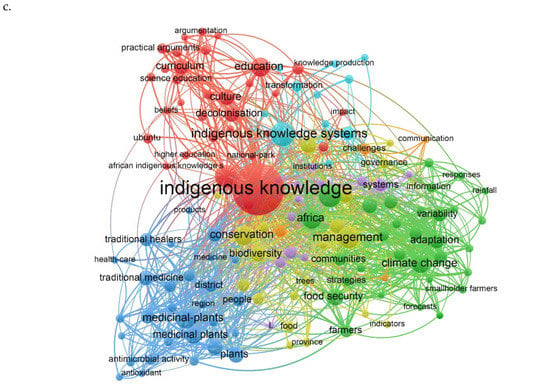

Figure 4 shows the analysis of all author keywords frequently co-occurring in IK literature from the global, African, and South African viewpoints, respectively. Figure 4a displays the IK global analysis, resulting in 964 keywords out of 13,157, and the results show seven different keyword clusters. Figure 4b shows the IK African analysis resulting in 232 keywords out of 3886; the results show six keyword clusters. Figure 4c highlights the IK South African analysis resulting in 141 keywords out of 2734, showing seven keyword clusters.

Figure 4.

Network visualization map of co-occurring keywords in indigenous knowledge literature—(a) global view, (b) African view, and (c) South African view—published from 1990 to 2020.

From the global perspective (Figure 4a), the red cluster was the most significant central grouping, closely related to the concept and occurrence of IK, the understanding of its practices, and the philosophies of local communities [74]. It ties to education and the decolonization of school curriculums, languages, and indigenous methodologies [12,74,75]. Publications in the red cluster explored IK concerning aspects including participatory research, South Africa, Canada, pedagogy, health, and ontology. Research on IK involving aspects such as participatory development could enable effective interventions, which in turn might inform and guide the development and implementation of local community policies [75]. The blue cluster was the second largest, closely allied with the concepts of management, conversation, resilience, patterns, ecology, science, geographic information systems, and strategies; these, in turn, all link with IK through environmental management. Environmental management itself can be addressed via local governments and other institutions using local wisdom and IK practices [12]. Further, environmental management research should involve indigenous people and their knowledge as key actors in the sustainable development of biodiversity [12,13].

The next-largest grouping after the blue cluster was the green cluster, which speaks to ethnobotany from an IK perspective. This cluster entails aspects such as medicinal plants, traditional medication, people, ethnobotanical surveys, districts, and regions. Traditional healers are still important within modern societies; they are often located within local communities and maintain a high social status that impacts local health practices; hence, traditional healing is part of the primary healthcare system [13]. Traditional ethnobotanical knowledge encompasses various plants used by indigenous communities for numerous purposes [16]. The purple cluster involves aspects of climate change, adaptation, disaster, mitigation, flood risk, drought, and weather, to name a few. The holistic view of indigenous people towards their environment, including their knowledge systems and practices, is key to climate change adaptation [17]. The olive cluster was minor compared to the other clusters, intricately linked to the concept of IK through aspects including agriculture, farmers, soil fertility, pest control, and vegetation. Traditional knowledge based on the physical environment is highly comprehensive; for instance, many farmers use traditional calendars to regulate and prepare agricultural activities [76]. The differences between global, African, and South African perspectives, respectively, are shown in the following keywords: “science” (global), “Africa” (African), and “medicinal plants” (South African) perspective.

3.3. Existing, Current, and Emerging Trend Topics for All Keywords on Indigenous Knowledge

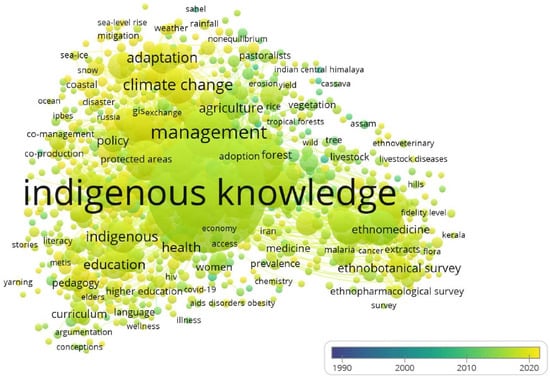

Figure 5 represents the results of an overlay visualization of all the existing, current, and emerging trends of all keywords based on IK literature from 1990 to 2020. The analysis of the trend topics identified 964 keywords (out of a total of 13,157), meeting the requirements. The minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set at a default of five by VOSviewer. The keywords recognized in the study specified relevant research hotspots over the last three decades, globally, and academics had used them to recognize research trends in the field. Colored indicators show the trend line from existing to emerging trends from 1990 to 2020. The navy-blue cluster indicates trend topics existing from the year 2000 to 2010, the turquoise blue cluster represents the most recent trend from 2010 to 2020, and lastly, the yellow cluster from 2020 indicates the emerging trend topics. Between 2000 and 2010, most research on IK focused on tree fodder, pest control, soil conservation, the Sahel, and the Indian Central Himalaya. From 2010 to 2020, research on IK focused on aspects including irrigation, trees, illness, HIV, benefits sharing, ethnoveterinary medicine, conservation, medicinal plants, IK, management, agriculture, culture, history, and Africa.

Figure 5.

Overlay visualization of existing, current, and emerging trends by all keywords on indigenous knowledge. Map Source: VOSviewer.

For centuries, farmers have used IK systems, skills, and practices for agricultural production and the conservation of natural resources [77]. Traditional healers and IK have played a prominent role in assisting scientific healthcare programs in the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic, thus contributing to allocating adequate natural resources to governments, medical, and health organizations [78]. Since 2020, IK research has focused more on climate change, adaptation, temperature, coronavirus disease (COVID-19), education, care, children, nutritional composition, crops, and seasonal and climate forecasts. When it comes to environmental and climate change, indigenous and rural communities are among the first to be impacted directly by impacts on the ecosystems and landscapes they inhabit [79]. These effects are exacerbated in these communities by their close association with/dependence on the environment and its resources [80].

With increasing interest in studies relating to IK, it is anticipated that future research will fuse studies dealing with IK practices and systems for the conservation of biodiversity, nature conservation, climate change mechanisms of mitigation and adaptation, environmental and disaster risk management, disease management, food security, and sustainable livelihoods for sustainable ecosystem management. Thereby, it is hoped that researchers will provide strong information on achieving the sustainable development of resilient communities. Over the decades, IK has had an increasing impact on academic disciplines such as ethnobotany, ecology, geography, ecological conservation and management, natural resources management, food security, well-being, and education [2]. There is a need to understand different perspectives on the sustainability of such change; there is a further need to respond to the ecological disasters brought about by driving forces including climate change [81]. Thus, various national and global agencies have been exploring the use of native and local knowledge as a foundation for resilience and adaptation in the face of rapid environmental alteration [6].

3.4. Network of Co-Authorship on Indigenous Knowledge by Countries

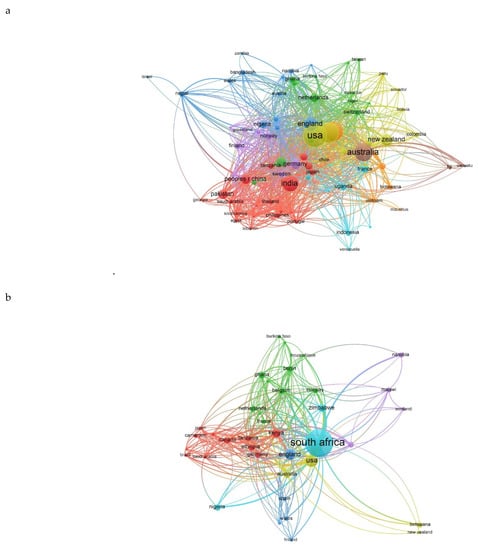

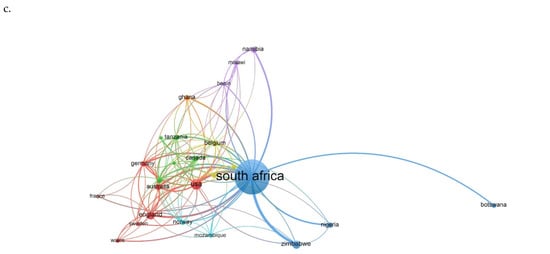

Figure 6 shows the countries that are the leaders in producing publications on the concept of IK from a global, African, and South African viewpoint. The IK global analysis identified thirty-eight countries out of ninety-four, showing eight affiliated groups (Figure 6a). While the IK African analysis identified forty-seven countries out of 801, the results show six related groups (Figure 6b). The IK South African analysis identified twenty-five countries out of the seventy-five, showing eight groups (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Network visualization map of publishing countries on indigenous knowledge literature: (a) global view, (b) African view, and (c) South African view.

Globally, countries show great collaboration, solidifying the stance of IK as a concept of interest and increasing popularity within the academic space. The African continent shows excellent collaborations between countries, with South Africa at the forefront, having numerous publications, author collaborations, and inter-country collaborations. South Africa is one of the few countries within the African continent that recognizes and documents the knowledge of indigenous people (such as the Khoi and San people). The indigenous people of South Africa are protected by the IK Policy, a framework that aims to stimulate and reinforce the impact of IK to promote social and economic improvement within the country. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) region has numerous publications on IK that focus on the decolonization of knowledge and culture. Between 2015 and 2017, the world witnessed a new revolution throughout South African universities, known as #feesmustfall; this called out for the decolonization of the educational system. It later echoed and extended into Europe, inspiring ongoing student-led initiatives across the United Kingdom [82]. Noyoo notes that within the SADC region, IK plays a pivotal role in local-level decision-making in agriculture, education, health, and social organizations [83].

In rural communities in developing countries, IK is easily accessible and used for the provision of daily livelihoods [84]. According to the World Health Organization, most Africans use indigenous medicines for health, social-cultural, and economic reasons. This is borne out by recent work by Moos, who indicated that in Africa, up to 80% of the population uses indigenous medicine for primary healthcare [85]. Within the African continent, indigenous traditional healers are essential and universally recognized within the healthcare system; they engage in an extensive range of practices, some classifying themselves as herbalists, spiritualists, or mediums, and others combining all these practices [86]. In South Africa, traditional doctors and medication also play a vital role in managing certain diseases, and the sale of traditional medication in rural communities reduces poverty and creates self-employment [85]. Again, looking at the continental scale, IK within Africa incorporates food processing and preservation, water management, health, and other significant components of life, such as spiritual being [87]. As in the global context, in acknowledgment of its significant role, IK is protected and promoted as a contributor toward socio-economic growth and sustainable development [85]. Within BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), South Africa dominates citations per document. South Africa also participates in various international collaborations [88]. However, rather than other African nations participating, several Global North countries, such as the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom, and Germany, appear to be collaborating with the BRICS nations in producing publications based on the African narrative of IK [74]. Participatory research integrating traditional knowledge to control environmental risk has increasingly gained popularity—from the Inuit in Canada to the Aboriginal communities of Northern Australia, as well as the Central Australian indigenous people [89].

3.5. Full-Text Literature Reading on IK

This paper provides insights into the various types of IK research conducted both from Global and African perspectives through a full-text reading of the top twenty highly cited publications from the dataset retrieved from WoS. The literature provides evidence on the recognition and incorporation of IK within sustainable development research, knowledge enhancement, and the development of ecological approaches, methodologies, and frameworks. It furthermore provides potential solutions and limitations of how IK has the ability to confront global change, ecological pressures, and other socio-economic and cultural changes. The literature contributed to the broader aspects of multidisciplinary knowledge dealing with ecological and sustainable development research. The readings from a global perspective with high citations paint a clear insight into how IK has been recognized and researched over the years. Firstly, an article by Berkes et al. [90] presents a study that indicates that there is a diversity of traditional/local practices for ecosystem management used by indigenous communities [91]. These practices include resource management, climate change, species management, and other ways of responding to and managing ecological shocks [92]. Agrawal argues that the distinctions between IK and Western knowledge are potentially ludicrous, as one epistemic and the other more practical. He furthermore points out that each kind of knowledge is potentially useful to certain people and communities [93] (p. 433). IK and Western knowledge should not be viewed as polar opposites; both knowledge systems share inherent similarities that should be harnessed to provide solutions to the current ecological state from a broad perspective [94]. Gadgil et al. [95] indicate in their study the importance of conserving the diversity of local cultures and their IK, as much as it is worthy to conserve biodiversity for sustainability.

African IK should be considered and understood globally as being inclined to religious ceremonies, traditional rituals, and other cultural practices and customs [96]. There is no well-developed framework on the integration of IK alongside scientific knowledge and how these may reduce community vulnerability to environmental hazards [97]. When developing sustainability frameworks, the science-policy community and government research organizations need to embrace various IK from local or indigenous communities [98]. Davis and Wagner [99] indicate a lack of reporting on the methods employed, and employing systematic approaches, especially to the critical issue of how local experts are identified within social science research. Sillitoe [100] emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary teamwork for the successful achievement of sustainable development through the contribution of the role played by IK and indigenous communities. However, research on indigenous communities and their knowledge needs to protect and safeguard the interests of indigenous people and their identities [101]. Bohensky and Maru [46] indicate that more meaningful and appropriate knowledge integration processes for research within indigenous communities need to be developed.

From the African context, Orlove et al. [102] examine how farmers in southern Uganda use indigenous climate knowledge for agricultural purposes. Such participatory approaches integrate farmers both as agents and consumers, in programs that use modern climate science to plan for and adapt to climate variability and change [103]. Gómez-Baggethun et al. [104], in their special feature, first focus on the resilience of IK. They explore the conditions that lead to its loss or persistence in the face of global change. Secondly, they look at the ways in which IK strengthens community resilience in response to the multiple shocks of global ecological change [104]. Alexander et al. [105] explore the linkages between indigenous climate-related narratives, documented temperature changes, and climate change impact studies. Their aim was to contribute to the integration of IK with scientific data and analysis so that IK can inform science for the benefit of indigenous people and their communities [105] (p. 447). Aswani et al. [106] analyze the drivers of various kinds of IK transformation, and they assess the directivity of those reported changes. Their results indicate that most studies are on ethnobotanical and medicinal knowledge [106] (p. 9). Makondoa and Thomas [107] advocate that both IK and scientific knowledge are significant, and there should be an integration of both through multiple evidence-based approaches for climate change adaptation and mitigation. They focus on African traditional society and combine oral history with the existing literature to examine IK’s awareness of climate change and related environmental hazards.

Davis [108] presents an overview study of IK among the Aarib, a group of camel pastoralists in southern Morocco, comparing it to the expert knowledge of Moroccan range managers. The paper submits that the Aarib IK has been overlooked and underprivileged compared to the expert knowledge of Moroccan range managers due to political, economic, and administrative reasons. Barrios et al. [109] have developed a participatory approach and a methodological guide to identify and classify local indicators of soil quality and relate them to technical soil parameters to provide farmers, extension workers, and scientists with a common language for the sustainable management of tropical soils and agriculture. Owusu-Ansah and Mji [26] attempt to raise awareness to include IK in the design and implementation of research, especially disability research, in Africa. They encourage that the Afrocentric paradigm is appropriate for African research, and it is important that emancipatory and participatory research methods are used that value and include IK and people. Mahwasane et al. [110] investigate the usage of medicinal plants in the treatment and prevention of diseases within the Lwamondo area in the Limpopo province, South Africa. The study records the medicinal plants and plant parts used for treating various human diseases by the traditional healers of the Lwamondo. Kalanda-Joshua et al. [111] conducted research on the indicators of IK used in weather, climate forecasting, and people’s perceptions of climate change and variability in Nessa Village, Southern Malawi. The study advocates for the incorporation of IK into scientific climate forecasts at local levels to enhance community resilience from the harsh impacts of climate change.

4. Policy Development and Implementation

Policymakers and implementers need to consider indigenous people and their knowledge when developing and implementing their policies. Indigenous communities have always been at the forefront of environmental conservation and maintenance within their local surroundings. Indigenous communities use IK for solving daily problems and situations, thus allowing them to understand and improve local conditions from their local perspective and provide solutions to such conditions [89]. In terms of the sustainable management and preservation of natural resources, with their deep-rooted local knowledge, indigenous people play a crucial role in assisting in the global adaptation and mitigation of global and climate change [112]. For indigenous communities, the incorporation of new skills and tools has always been essential; the blending together of new and old ways allows the lifestyle of indigenous communities to evolve and adapt to trends [8]. The unique food systems of indigenous communities are secured by sustainable livelihood practices that are adapted to specific local ecosystems [112]. The direct linkages of IK to the ecosystem and human well-being that foster sustainability are not extensively researched in the African context; indeed, there is a need to develop models that can direct quantitative and qualitative data collection to allow enhanced predictions—including on how ecosystems benefit humans and how activities/strategies affect biodiversity and the amenities it provides [113].

When developing legislative frameworks and strategies, the importance of conserving and protecting Indigenous communities, their knowledge, and systems needs to be considered in Africa [114]. Innovative policies should be inclusive of poverty reduction, climate challenges, and the restoration of biodiversity through the application of IK [83]. For instance, in Zimbabwe, the IK for agriculture provides a fundamental value for securing and sustaining food production and preserving cultural rights [115]. In the context of Botswana, communities in and around the Okavango Delta rely on natural resources and IK to manage and sustain livelihoods and the environment [116]. Other prevalent IK unique to the Okavango region includes the Molapo farming system and the migration system in response to shocks from ecological hazards [117]. Indigenous communities possess considerable problem-solving solutions to livelihoods, climate, and landscape change, and they deal with issues of poverty, diseases, and land-use management daily. Therefore, policy developers need to involve indigenous people from the earliest planning stages as well as in the monitoring and evaluation processes. Indigenous peoples are often recognized as being particularly vulnerable to the effects of environmental change [79]. Indigenous communities use IK transmitted from generation to generation through experiences and observations that developed ways of environmental management and enabled sustainable livelihoods [118]. Apart from valuing sacred places, taboos, and customs, indigenous communities have their systems of preserving and conserving the environment [119].

5. Conclusions

This study has explored the global scientific literature on IK that has been developed over the last thirty years (1990–2020). The concept of IK has drawn increased attention globally, albeit with limited research work done from the African narrative. The bibliometric analysis conducted using VOSviewer showed that while IK is well-represented in the literature worldwide, there appears to be some deficiency in terms of African representation. This could be due to the fact that the literature written by African scholars does not meet the high critical criteria of international journal publishers. The results obtained from the bibliometric analysis of this paper signify that research on IK has significantly increased over the decades and particularly in the year 2020. The latter can be ascribed to the association of IK practices with the COVID-19 pandemic—involving ethnobotanical and traditional medicine and socio-economic research trends. Key results of this study provide future researchers with insightful emerging trend topics such as dealing with climate change, the necessary adaptation strategies including the shifts in temperature and seasonal climate forecasts necessary for crop production, responses to COVID-19, as well as topics related to childcare, education, and nutritional composition. Future research trends are likely to provide beneficial recommendations contributing to knowledge and development for multidisciplinary research studies. From an African perspective, South Africa is the dominant research location within the African continent regarding IK publication, with other counties on the continent lagging in this respect. What can be observed is that other countries outside the African continent are telling the African narrative—primarily countries from the Global North. This might suggest that the authentic African narrative is not clearly reflected within the scientific literature. Another reason for much of the research being generated in the Global North might be that the researchers are of African origin, and perhaps they are based in other continents for academic reasons such as international collaborations, research funding, and recognition. The literature from the full-text literature reading indicates that though much research has been done on IK, there is a lack of research based on the integration of IK and scientific knowledge to foster resilient communities, cater to ecological development strategies, and foster sustainable development and growth. There is a need for more research on how to develop strategic approaches, methodologies, and frameworks that are inclusive of IK, as it has the potential to provide solutions to the current ecological and socio-economic crises faced by the world. Most African IK research studies are based on ethnobotany, cultural traditions and customs, and agriculture. This study encourages transdisciplinary research approaches that will strengthen the significance of IK as an integral part of scientific research, strategies, and developmental frameworks dealing with ecological conservation, socio-economic issues, and sustainable resilience and development, not only for indigenous communities but including the modern environment and world. Such approaches should also enhance the importance of IK participatory research so that policy development and implementation will better contribute to attaining resilient communities and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L.M., W.M. and N.C.; methodology, O.L.M.; software, O.L.M.; validation, W.M., V.R.-P. and O.L.M.; formal analysis, O.L.M.; investigation, O.L.M.; resources, W.M.; data curation, O.L.M., W.M. and V.R.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.L.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M., N.C. and V.R.-P.; visualization, O.L.M.; supervision, W.M. and N.C.; project administration, O.L.M. and W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)—Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) Inter-bursary Support Programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank. The World Bank. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples#:~:text=There%20are%20an%20estimated%20476,percent%20of%20the%20extreme%20poor (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Magni, G. Indigenous knowledge and implications for the sustainable development agenda. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Sikutshwa, L.; Shackleton, S. Acknowledging Indigenous and Local Knowledge to Facilitate Collaboration in Landscape Approaches—Lessons from a Systematic Review. Land 2020, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyong, C.T. Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Development in Africa: Case Study on Central Africa. In Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Sustainable Development: Relevance for Africa; Boon, E.K., Hens, L., Eds.; Kamla-Raj Enterprises: New Delhi, India, 2005; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaa, D.D.; Waswa, F. Role of indigenous knowledge systems in the conservation of the bio-physical environment among the Teso community in Busia County-Kenya. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 10, 467–475. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Tsai, H.-M.; Bayrak, M.; Lin, Y.-R. Indigenous resilience to disasters in Taiwan and beyond. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boafo, Y.A.; Saito, O.; Kato, S.; Kamiyama, C.; Takeuchi, K.; Nakahara, M. The role of traditional ecological knowledge in ecosystem services management: The case of four rural communities in Northern Ghana. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2015, 12, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakashim, D.; Rubis, J.; Bates, P.; Ávila, B. Local Knowledge, Global Goals; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchi, F. Western science and traditional knowledge: Despite their variations, different forms of knowledge can learn from each other. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, N.J.; Gregory, R.; Brooks, C.; Failing, L.; Satterfield, T. From invisibility to transparency: Identifying the implications. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape sustainability science: Ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, C.A. The relevance of indigenous knowledge systems in local governance toward environmental management for sustainable development: A case of Bulawayo City Council, Zimbabwe. Quest J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikhyoussef, A.; Shapi, M.; Matengu, K.; Ashekele, H.M. Ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plant use by traditional healers in Oshikoto region, Namibia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Seikh, S.; Pandey, R. Nexus between indigenous ecological knowledge and ecosystem services: A socio-ecological analysis for sustainable ecosystem management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IFAD. International Fund for Agricultural Development. 6 July 2020. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/story/indigenous-knowledge-and-resilience-in-a-covid-19-wor-1 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Komal; Ramchiary, N.; Singh, P. Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, J.L. Chapter 14—Societal adaptation to climate change. In The Impacts of Climate Change: A Comprehensive Study of Physical, Biophysical, Social, and Political Issues, 1st ed.; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Emeagwali, G.; Shizha, E. African Indigenous Knowledge and the Sciences: Journeys into the Past and Present; Emeagwali, G., Shizha, E., Eds.; Sense Publisher: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masinde, M.; Bagula, A. ITIKI: Bridge between African indigenous knowledge and modern. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2011, 7, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.O.; Seleti, Y.N. African indigenous knowledge systems and relevance of higher education in South Africa. Int. Educ. J. Comp. Perspect. 2013, 12, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mawere, M. Indigenous knowledge and public education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. Spectr. 2015, 50, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Grantham, H.S.; Watson, J.E.M.; Alvarez, S.J.; Simmonds, J.S.; Rogéliz, C.A.; Da Silva, M.A.; Forero-Medina, G.; Etter, A.; Nogales, J.; et al. Minimising the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services in an intact landscape under risk of rapid agricultural development. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, D.; Begay, A.; Burgasser, I.; Hawkins, K.I.; Kimura, N.; Maryboy, L.; Peticolas, G.; Rudnick, D.S.; Tuttle, S. Collaboration with integrity: Indigenous knowledge in 21st century astronomy. BAAS 2019, 57, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, T.F.; Scheer, A.M. Collaborative engagement of local and traditional knowledge and science in marine environments: A review. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, O.R.; Garbutt, A.; Skov, M.; Möller, I.; Alexander, M.; Ballinger, R.; Wyles, K.; Smith, G.; McKinley, E.; Griffin, J.; et al. A framework linking ecosystem services and human well-being: Saltmarsh as a case study. People Nat. 2019, 1, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Ansah, F.E.; Mji, G. African indigenous knowledge and research. Afr. J. Disabil. 2013, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapara, J. Indigenous knowledge systems in Zimbabwe: Juxtaposing post colonial theory. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2009, 3, 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A. The ecological role of biodiversity in agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1999, 74, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Risiro, J.; Tshuma, D.T.; Basikiti, A. Indigenous knowledge systems and environmental management: A case study of Zaka District, Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2013, 2, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Langil, S. Introduction to Indigenous Knowledge. In The Overstory Book: Cultivating Connections with Trees, 2nd ed.; Elevitch, C., Ed.; People, Land and Water Program Initiative, IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, D.M. Using Indigenous in Agricultural Development; World Bank Discussion Paper. Number 127; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Horsthemke, K. Indigenous knowledge—Conceptions and misconceptions. J. Educ. 2004, 32, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake, S.G.J.N. Indigenous knowledge as a key to sustainable development. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilder, B.T.; O’Meara, C.; Monti, L.; Nabhan, G.P. The importance of indigenous knowledge in curbing the loss of language and biodiversity. BioScience 2016, 66, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalawole, P. Local knowledge utilization and sustainable rural development in the 21st century. Indig. Knowl. Monit. 2001, 9, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, G.D. Agricultural Deskilling and the Spread of Genetically Modified Cotton in Warangal. Curr. Anthropol. 2007, 48, 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mapira, J.; Mazambara, P. Indigenous knowledge systems and their implications for sustainble development in Zimbabwe. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2013, 15, 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS). 2021. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/links (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Hiwasaki, L.; Luna, E.; Syamsidik; Shaw, R. Process for integrating local and indigenous knowledge with science for hydro-meteorological disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in coastal and small island communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 10, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Settee, P. Indigenous Knowledge: Multiple Approaches. Indig. Philos. Crit. Educ. A 2011, 379, 434–450. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, E.A. Indigenous Knowledge in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities; CEPD: Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppers, C.A.O. Culture, Indigenous Knowledge and Development: The Role of the University; CEPD: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flavier, J.M. The regional program for the promotion of indigenous knowledge in Asia. In The Cultural Dimension of Development: Indigenous Knowledge Systems; Warren, D.M., Slikkerveer, L.J., Brokensha, D., Eds.; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1995; pp. 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Enock, C.M. Indigenous knowledge systems and modern weather forecasting: Exploring the linkages. J. Agric. Sustain. 2013, 2, 98–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kugara, S.L.; Kugedera, A.T.; Sakadzo, N.; Chivhenge, E.; Museva, T. The role of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) in climate change. In Handbook of Research on Protecting and Managing Global Indigenous Knowledge System; Tshifhumulo, R., Makhanikhe, T.J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bohensky, E.L.; Maru, Y. Indigenous knowledge, science, and resilience: What have we learned from a decade of international literature on “integration”? Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sangha, K.K.; Preece, L.; Villarreal-Rosas, J.; Kegamba, J.J.; Paudyal, K.; Warmenhoven, T.; RamaKrishnan, P. An ecosystem services framework to evaluate indigenous and local peoples’ connections with nature. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, V. The human–nature relationship and its impact on health: A critical review. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betley, E.C.; Sigouin, A.; Pascua, P.; Cheng, S.H.; MacDonald, K.I.; Arengo, F.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Caillon, S.; Isaac, M.E.; Jupiter, S.D.; et al. Assessing human well-being constructs with environmental and equity aspects: A review of the landscape. People Nat. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.K.; Smith, L.M.; Case, J.L.; Linthurst, R.A. A review of the elements of human well-being with an emphasis on the contribution of ecosystem services. Ambio 2012, 41, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, R.; Adem, C.; Alangui, W.V.; Molnár, Z.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Z.; Bridgewater, P.; Tengö, M.; Thaman, R.; Adou Yao, C.Y.; Berkes, F.; et al. Working with Indigenous, local and scientific knowledge in assessments of nature and nature’s linkages with people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Berardi, A. Bridging indigenous and scientific knowledge. Science 2016, 352, 1274–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadykalo, N.; López-Rodriguez, M.D.; Ainscough, J.; Droste, N.; Ryu, H.; Ávila-Flores, G.; Le Clec’h, S.; Muñoz, M.C.; Nilsson, L.; Rana, S.; et al. Disentangling ‘ecosystem services’ and ‘nature’s contributions to people’. Ecosyst. People 2019, 15, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whyte, K.P. On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: A philosophical study. Ecol. Process. 2013, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marques, B.; Freeman, C.; Carter, L.; Zari, M.P. Conceptualising therapeutic environments through culture, indigenous knowledge and landscape for healthand well-being. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.J.; Gordon-Nesbitt, R.; Elsden, E.; Chatterjee, H.J. The role of cultural, community and natural assets in addressing societal and structural health inequalities in the UK: Future research priorities. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2021, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maas, J.; van Dillen, S.; Verheij, R.; Groenewegen, P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relationbetween green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sullivan, W.; Kuo, F.; Depooter, S. The fruit of urban nature: Vital neighborhood spaces. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Whitehead, P.J. Healthy country: Healthy people? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Public Health 2005, 29, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, K.; Rollins, J.; Yan, E. Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics 2018, 115, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Philip, K.S. Indigenous knowledge: Science and technology studies. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlads, 2001; pp. 7292–7297. [Google Scholar]

- Szomszor, M.; Adams, J.; Fry, R.; Gebert, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Potter, R.W.K.; Rogers, G. Interpreting bibliometric data. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2021, 5, 628703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrizo-Sainero, G. Toward a concept of bibliometrics. J. Span. Res. Inf. Sci 2000, 1, 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fu-Hsuan, L.; Chuan-Hang, Y.; Yu-Chao, C. Bibliometric analysis of articles published in journal of dental sciences from 2009 to 2020. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 137, 500–516. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Sachet, E.; Blundo-Canto, G.; Vanegas, M.; Quintero, M. To what extent have the links between ecosystem services and human well-being been researched in Africa, Asia, and Latin America? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S.; Mura, P.; Wijesinghe, S.N. A systematic review of systematic reviews in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selçuk, A.A. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019, 57, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleka, J.R.; Ngulube, P. Indigenous knowledge in Africa: A bibliometric analysis of publishing patterns. Publ. Res. Q. 2019, 35, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwanya, T.; Kiplang’at, J. Indigenous knowledge research in Kenya: A bibliometric analysis. In Proceedings of the 11th International Knowledge Management in Organizations Conference on The Changing Face of Knowledge Management Impacting Society, Hagen, Germany, 25–28 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi, M.K.; Loring, P.A. Hidden participants and unheard voices? A systematic review of gender, age, and other influences on local and traditional knowledge research in the North. FACETS 2018, 3, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, M.; Ajaps, S.; Molthan-Hill, P. A Systematic review of the deployment of indigenous knowledge systems towards climate change adaptation in developing world contexts: Implications for climate change education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Nakagawa, H. Validation of indigenous knowledge for disaster resilience against river flooding and bank erosion. In Science and Technology in Disaster Risk Reduction in Asia; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, P.; Marzano, M. Future of indigenous knowledge research in development. Futures 2009, 41, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. Agriculture, traditional. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Akullo, D.; Kanzikwera, R.; Birungi, P.; Alum, W.; Aliguma, L.; Barwogeza, M. Indigenous knowledge in agriculture: A case study of the challenges in sharing knowledge of past generations in a globalized context in Uganda. In Proceedings of this World Library and Information Congress: 73rd IFLA General Conference and Council, Durban, South Africa, 19–23 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. HIV/AIDS: Traditional Healers, Community Self-assessment, and Empowerment; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; King, N.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Pearce, T.; McDowell, G.; Harper, S.L. The resilience of indigenous peoples to environmental change. One Earth 2020, 2, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Challenges and Opportunities for Indigenous Peoples’ Sustainability. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2021/04/indigenous-peoples-sustainability/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Malhi, Y.; Franklin, J.; Seddon, N.; Solan, M.; Turner, M.G.; Field, C.B.; Knowlton, N. Climate change and ecosystems: Threats, opportunities and solutions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noyoo, N. Indigenous knowledge systems and their relevance for sustainable development: A case of Southern Africa. In Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Sustainable Development: Relevance for Africa; Hens, L., Boon, E.K., Eds.; Kamla-Raj Enterprises: New Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen, J.S.; Hooli, L. Indigenous knowledge and developing countries’ innovation systems: The case of Namibia. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2017, 1, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, J.S.; Roberts, B. Human Sciences Research Council. 2021. Available online: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/november-/local-is-lekker (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Levers, L.L. Traditional healing as indigenous knowledge: Its relevance to HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa and the implications for counselors. J. Psychol. Afr. 2006, 16, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, D. Indigenous knowledge and practice for climate change adaptation. In Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene; DellaSala, D., Goldstein, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Leviston, Z.; Walker, I.; Green, M.; Price, J. Linkages between ecosystem services and human wellbeing: A Nexus Webs approach. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-Farashbandi, F.; Geraei, E.; Siamaki, S. Study of co-authorship network of papers in the Journal of Research in Medical Sciences using social network analysis. J. Res. Med Sci. 2014, 19, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Manna, S. Indigenous knowledge and grass-root challenges. In Tribal India’s Traditional Wisdom and Indigenous Resource Management; Bera, G.K., Svd, K.J., Eds.; Abhijeet Publications: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditonal tcological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, S. Roles of traditional ecological knowledge for biodiversity conservation. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2017, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stori, F.T.; Peres, C.M.; Turra, A.; Pressey, R.L. Traditional ecological knowledge supports ecosystem-based management in disturbed coastal marine social-ecological systems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agrawal, A. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Dev. Change 1995, 26, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maweu, J.M. Indigenous ecological knowledge and modern western ecological knowledge: Complementary, not contradictory. J. Philos. Assoc. Kenya 2011, 3, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil, M.G.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 51–156. [Google Scholar]

- Breidlid, A. Culture, indigenous knowledge systems and sustainable development: A critical view of education in an African context. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Kelman, I.; Taranis, L.; Suchet-Pearson, S. Framework for integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge for disaster risk reduction. Disasters 2009, 34, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengö, M.; Brondizio, E.S.; Elmqvist, T.; Malmer, P.; Spierenburg, M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 2014, 43, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, A.; Wagner, J.R. Who knows? On the importance of identifying “experts” when researching local ecological knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 2003, 31, 463–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, P. The development of indigenous knowledge: A new applied anthropology. Curr. Anthropol. 1998, 39, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agrawal, A. Indigenous knowledge and the politics of classification. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2002, 54, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlove, B.; Roncoli, C.; Kabugo, M.; Majugu, A. Indigenous climate knowledge in southern Uganda: The multiple components of a dynamic regional system. Clim. Chang. 2009, 100, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ubisi, N.R.; Kolanisi, U.; Jiri, O. Comparative review of indigenous knowledge systems and modern climate science. Ubuntu J. Confl. Transform. 2019, 8, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Corbera, E.; Reyes-García, V. Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, C.; Bynum, N.; Johnson, E.; King, U.; Mustonen, T.; Neofotis, P.; Oettlé, N.; Rosenzweig, C.; Sakakibara, C.; Shadrin, V.; et al. Linking indigenous and scientific knowledge of climate change. BioScience 2011, 61, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aswani, S.; Lemahieu, A.; Sauer, W.H. Global trends of local ecological knowledge and future implications. PLoSONE 2018, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makondoa, C.C.; Thomas, D.S.G. Climate change adaptation: Linking indigenous knowledge with western science for effective adaptation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 88, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.K. Indigenous knowledge and the desertification debate: Problematising expert knowledge in North Africa. Geoforum 2005, 36, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E.; Delve, R.; Bekunda, M.; Mowo, J.; Agunda, J.; Ramisch, J.; Trejo, M.; Thomas, R. Indicators of soil quality: A South–South development of a methodological guide for linking local and technical knowledge. Geoderma 2006, 135, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahwasane, S.T.; Middleton, L.; Boaduo, N. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used by the traditional healers of the Lwamondo area, Limpopo province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 88, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalanda-Joshua, M.; Ngongondo, C.; Chipeta, L.; Mpembeka, F. Integrating indigenous knowledge with conventional science: Enhancing localised climate and weather forecasts in Nessa, Mulanje, Malawi. Phys. Chem. Earth 2011, 36, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, M.P. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). 2021. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/indigenous-peoples (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Balmford, L.; Bennun, B.; Brink, D.; Cooper, I.M.; Côté, P.; Crane, A.; Dobson, N.; Dudley, I.; Dutton, R.E.; Green, R.D.; et al. The convention on biological diversity’s 2010 target. Science 2005, 307, 212–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R. Legal Framework Protected Areas: South Africa; IUCN: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tharakan, J. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge into Appropriate Technology Development and Implementation. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2015, 7, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.; Wilk, J.; Kgathi, D.L.; Bendsen, H.; Ngwenya, B.N.; Mosepele, K. Indigenous knowledge, livelihoods and government policy in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. In Rural Livelihoods, Risk and Political Economy; Kgathi, D.L., Ngwenya, B.N., Wilk, J., Eds.; Okavango Delta, Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, L.M. Migration and Environmental Hazards. Popul. Environ. 2005, 26, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanza, N.; Musakwa, W. “rees Are Our Relatives”: Local perceptions on forestry resources and implications for climate change mitigation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J. The Gaia Atlas of First Peoples: A Future for the Indigenous World; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).