How Governance Tools Facilitate Citizen Co-Production Behavior in Urban Community Micro-Regeneration: Evidence from Shanghai

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

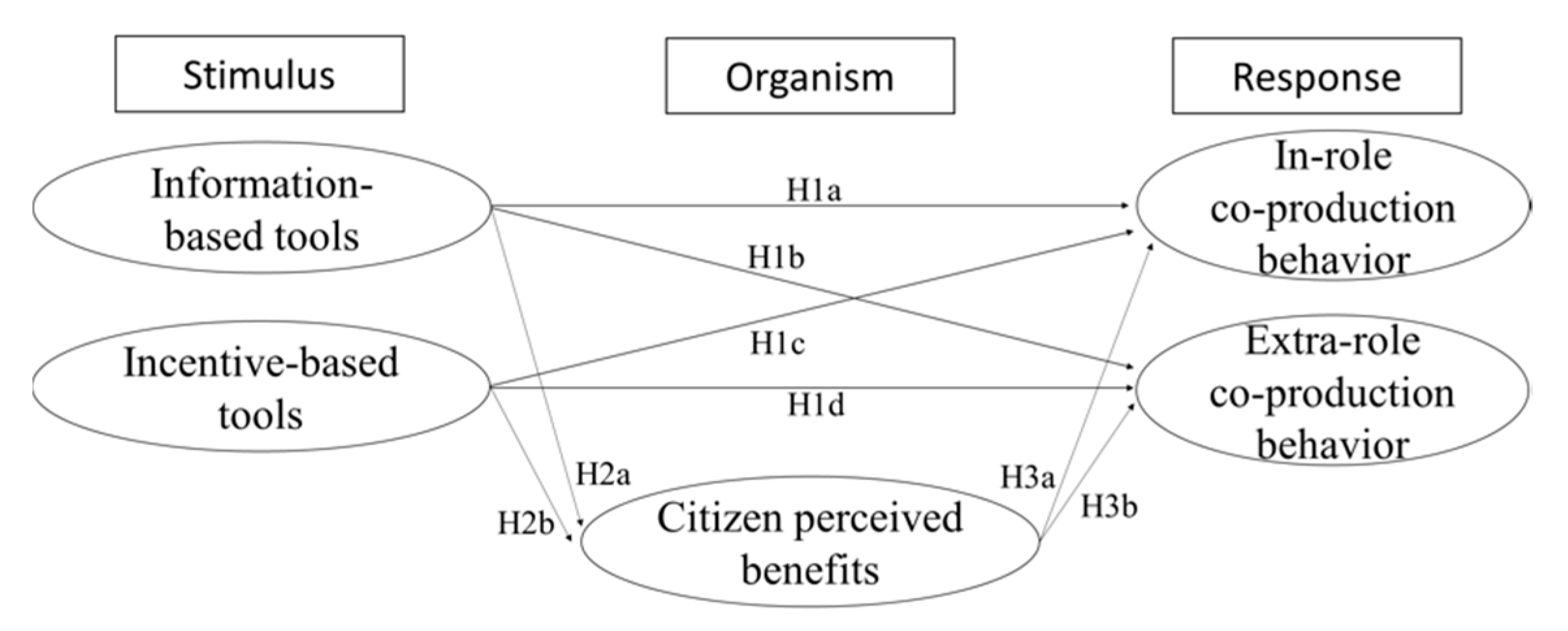

3. Research Framework and Hypothesis

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Variables

3.2. Hypothesis Propositions

4. Research Method

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Measures

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Measurement Reliability and Validity

5.2. Descriptive Analysis

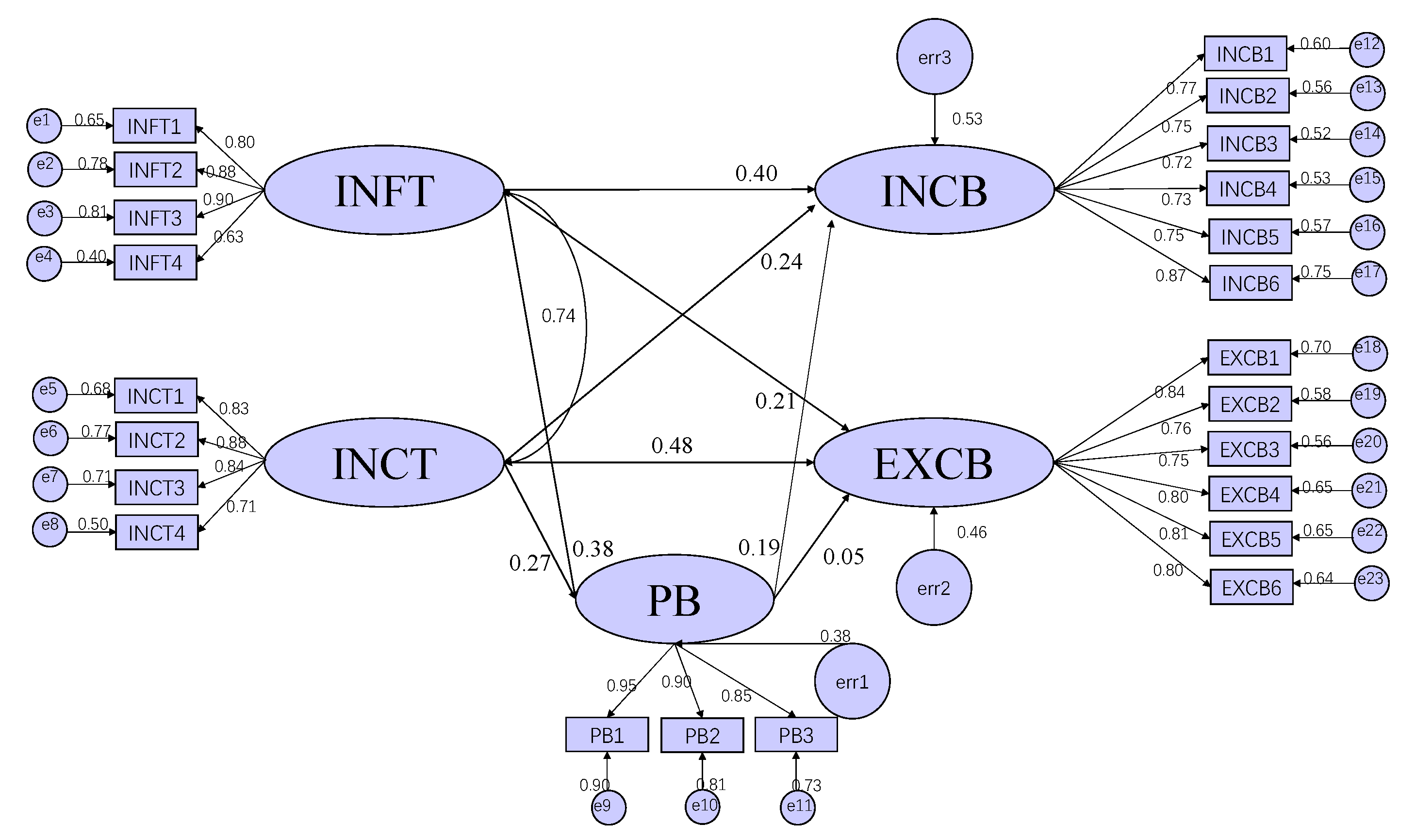

5.3. Structural Model Evaluation

5.4. Mediator Effect Evaluation

6. Discussions

6.1. The Differentiated Effects of Governance Tools on Citizen Co-Production Behavior

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Hui, E.C.; Liang, C.; Yip, T.L. Impact of semi-obnoxious facilities and urban renewal strategy on subdivided units. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 91, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fu, X.Y.; Han, Q.Y.; Huang, R.P.; Zhuang, T.Z. Research on the collaborative governance of urban regeneration based on a Bayesian network: The case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Poortinga, W. Built environment, urban vitality and social cohesion: Do vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, X. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Community Public Open Space Renewal: A Case Study of the Ruijin Community, Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruani, T.; Amit-Cohen, I. Open space planning models: A review of approaches and methods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Underlying relationships between public urban green spaces and social cohesion: A systematic literature review. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 24, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Bragg, R.; Pencheon, D.; Wood, C.; Depledge, M.H. Improving health and wellbeing independently of GDP: Dividends of greener and prosocial economies. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2016, 26, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Liu, X.S.; Vedlitz, A. Issue-specific knowledge and willingness to coproduce: The case of public security services. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 1464–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, V.; Osborne, S.P.; Brandsen, T. Patterns of Co-Production in Public Services: Some Concluding Thoughts. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T.; Sancino, A.; Sicilia, M. Varieties of Participation in Public Services: The Who, When, and What of Coproduction. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, J.; Brandsen, T.; Honingh, M. Restoring Trust through the Co-Production of Public Services: A theoretical elaboration. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, J. Why Do Public-Sector Clients Coproduce? Toward a Contingency Theory. Adm. Soc. 2002, 34, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C.C.; Margetts, H.Z. The Tools of Government in the Digital Age; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, S.; Zhang, Y. Coproduction of community public service evidence from China s community foundations. J. Chin. Gov. 2020, 5, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.C. Citizen, Customer, Partner: Rethinking the Place of the Public in Public Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.K.; Jakobsen, M. Influencing Citizen Coproduction by Sending Encouragement and Advice: A Field Experiment. Int. Public Manag. J. 2015, 18, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M. Can Government Initiatives Increase Citizen Coproduction? Results of a Randomized Field Experiment. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 23, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.C.; Nielsen, H.S.; Thomsen, M.K. How to Increase Citizen Coproduction: Replication and Extension of Existing Research. Int. Public Manag. J. 2018, 23, 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Van Ryzin, G.G.; Loeffler, E.; Parrado, S. Activating Citizens to Participate in Collective Co-Production of Public Services. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bovaird, T.; Stoker, G.; Jones, T.; Loeffler, E.; Roncancio, M.P. Activating collective co-production of public services: Influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, H.; Sidortsov, R. Sorting out a problem: A co-production approach to household waste management in Shanghai, China. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Hu, B.; Liu, T.; Fang, L. Can co-production be state-led? Policy pilots in four Chinese cities. Environ. Urban. 2018, 31, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tu, X. Understanding the Role of Nonprofit Organizations in the Provision of Social Services in China: An Exploratory Study. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2021, 32, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Parks, R.B.; Whitaker, G.P. Do We Really Want to Consolidate Urban Police Forces? A Reappraisal of Some Old Assertions. Public Adm. Rev. 1973, 33, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudney, J.L.; England, R.E. Toward a Definition of the Coproduction Concept. Public Adm. Rev. 1983, 43, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Honingh, M. Distinguishing different types of co-production: A conceptual analysis based on the classical definitions. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 76, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Rong, Z. The Mechanism to Form Community Coproduction in China: A Case Study on the Renewal of R Community in Shanghai. J. Shanghai Adm. Inst. 2021, 22, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.S.; Zhang, F.D.; Xue, B. How is It Possible to Renew Urban Communities from the Inside Out? Taking X Community Renewal Governance as an Example. J. Public Manag. 2022, 19, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Brandsen, T.; Pestoff, V. Co-production, the third sector and the delivery of public services. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P.; Radnor, Z.; Strokosch, K. Co-production and the Co-creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osborne, S.P.; Strokosch, K. It Takes Two to Tango? Understanding the Co-production of Public Services by Integrating the Services Management and Public Administration Perspectives. Br. J. Manag. 2013, 24, S31–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Eijk, C.J.A.; Steen, T.P.S. Why People Co-Produce: Analysing citizens’ perceptions on co-planning engagement in health care services. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, M.; Sancino, A.; Nabatchi, T.; Guarini, E. Facilitating co-production in public services: Management implications from a systematic literature review. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. Public Policy and Behavior Change. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, S.L. Citizen Participation in the Coproduction of Urban Services. Urban Aff. Q. 1984, 19, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.C.; Nielsen, H.S. Reading Intervention with a Growth Mindset Approach Improves Children’s Skills. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12111–12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.C.; Chung, K.C.; Tsai, M.Y. How to Achieve Sustainable Development of Mobile Payment through Customer Satisfaction—The SOR Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer Value Co-Creation Behavior: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.; James, O. Central State Steering of Local Collaboration: Assessing the Impact of Tools of Meta-governance in Homelessness Services in England. Public Organ. Rev. 2008, 8, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Khoa, B. Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terman, J.N.; Kassekert, A.; Feiock, R.C.; Yang, K. Walking in the Shadow of Pressman and Wildavsky: Expanding Fiscal Federalism and Goal Congruence Theories to Single-Shot Games. Rev. Policy Res. 2016, 33, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Langley, A.; Beland, F.; Denis, J.L. Governance, Power, and Mandated Collaboration in an Interorganizational Network. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 150–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.; Jilke, S.; Tummers, L.; Bekkers, V. Financial Rewards Do Not Stimulate Coproduction: Evidence from Two Experiments. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Eijk, C.J.A.; Steen, T.P.S. Why Engage in Co-Production of Public Services? Mixing Theory and Empirical Evidence. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, V. Collective Action and the Sustainability of Co-Production. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrado, S.; Van Ryzin, G.G.; Bovaird, T.; Löffler, E. Correlates of Co-production: Evidence from a Five-Nation Survey of Citizens. Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, Y.; Lan, H.; Zhang, X.; He, Y. Confirmatory Analysis of the Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on Ecosystem Service Value Variation Based on the Structural Equation Model—A Case Study in Sichuan Province. Land 2022, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Namisango, F.; Kang, K.; Beydoun, G. How the structures provided by social media enable collaborative outcomes: A study of service co-creation in nonprofits. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, A.-M.; Namkung, Y. The Impact of the Perceived Values of Social Network Services (SNSs) on Brand Attitude and Value-Co-Creation Behavior in the Coffee Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J. Impact of Transformational Leadership on Follower Development and Performance: A Field Experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 76, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abab, S.A.; Wakjira, F.S.; Negash, T.T. Factors Influencing the Formalization of Rural Land Transactions in Ethiopia: A Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Land 2022, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.P. Process Mechanism and Innovation Strategy of Public Service Co-Production: Taking Public Library Service as Example. Library Tribune. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/44.1306.G2.20220104.1101.002.html (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Zhou, L.Y. How does Hierarchical Intervention Affect Collaborative Governance in China? A Case Study of Environmental Collaboration in Yangtze River Delta Region. J. Public Adm. 2020, 13, 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y. Impact of customer-oriented organizational socialization on customers’ value co-creation behaviors. J. Technol. Econ. 2018, 37, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brudney, J.L.; Cheng, Y. Defining and Measuring Coproduction: Deriving Lessons from Practicing Local Government Managers. Public Adm. Rev. 2022. Online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciai, C.; Capano, G. Policy instruments at work: A meta-analysis of their applications. Public Adm. 2021, 99, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W. The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Mangi, E.; Heath, T.; Ye, C.; Wang, L. An Analysis of Residents’ Social Profiles Influencing Their Participation in Community Micro-Regeneration Projects in China: A Case Study of Yongtai Community, Guangzhou. Land 2022, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandeya, G.P.; Shrestha, S.K. Does Citizen Participation Improve Local Planning? An Empirical Analysis of Stakeholders Perceptions in Nepal. J. South Asian Dev. 2019, 11, 276–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Gutierrez, J.; Rutherford, A.; Nicholson-Crotty, S. Types of Coproduction and Differential Effects on Organizational Performance: Evidence from the New York City School System. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.H.; Wu, J.P. Criticism of the critique of rational man hypothesis. J. Chongqing Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2015, 21, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Index | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 179 | 44.2 |

| Female | 226 | 55.8 | |

| Age | Under 30 | 31 | 7.7 |

| 31–40 | 51 | 12.6 | |

| 41–50 | 54 | 13.3 | |

| 51–60 | 125 | 30.9 | |

| 61–70 | 133 | 32.8 | |

| 71 and above | 11 | 2.7 | |

| Education | Primary school | 15 | 3.7 |

| Junior high school | 72 | 17.8 | |

| High school | 150 | 37.0 | |

| Bachelor’s | 125 | 30.9 | |

| Post-graduate | 43 | 10.6 | |

| Employment | Work or study | 153 | 37.8 |

| Retired | 218 | 53.8 | |

| Stay-at-home parent | 31 | 7.7 | |

| Others | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Marriage | Married | 348 | 85.9 |

| Unmarried | 57 | 14.1% |

| Variables | Items | Standard Estimate | Mean Value | S.D. | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-role co-production behavior (INCB) | INCB1 | 0.771 *** | 3.39 | 0.800 | 0.886 | 0.895 | 0.588 |

| INCB2 | 0.755 *** | ||||||

| INCB3 | 0.724 *** | ||||||

| INCB4 | 0.722 *** | ||||||

| INCB5 | 0.755 *** | ||||||

| INCB6 | 0.863 *** | ||||||

| Extra-role co-production behavior (EXCB) | EXCB1 | 0.836 *** | 3.33 | 0.812 | 0.902 | 0.911 | 0.632 |

| EXCB2 | 0.767 *** | ||||||

| EXCB3 | 0.750 *** | ||||||

| EXCB4 | 0.802 *** | ||||||

| EXCB5 | 0.809 *** | ||||||

| EXCB6 | 0.802 *** | ||||||

| Information-based tools (INFTs) | INFT1 | 0.804 *** | 3.28 | 0.866 | 0.881 | 0.885 | 0.661 |

| INFT2 | 0.882 *** | ||||||

| INFT3 | 0.903 *** | ||||||

| INFT4 | 0.637 *** | ||||||

| Incentive-based tools (INCTs) | INCT1 | 0.826 *** | 3.40 | 0.875 | 0.886 | 0.888 | 0.666 |

| INCT2 | 0.879 *** | ||||||

| INCT3 | 0.844 *** | ||||||

| INCT4 | 0.704 *** | ||||||

| Perceived benefits (PBs) | PB1 | 0.950 *** | 3.48 | 0.940 | 0.926 | 0.928 | 0.812 |

| PB2 | 0.898 *** | ||||||

| PB3 | 0.852 *** |

| INCB | EXCB | INFT | INCT | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INCB | 0.767 | ||||

| EXCB | 0.735 *** | 0.795 | |||

| INFT | 0.680 *** | 0.576 *** | 0.813 | ||

| INCT | 0.620 *** | 0.649 *** | 0.741 *** | 0.816 | |

| PB | 0.555 *** | 0.433 *** | 0.585 *** | 0.555 *** | 0.901 |

| INCB | EXCB | INFT | INCT | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INCB | 1 | ||||

| EXCB | 1 | ||||

| INFT | 0.623 ** | 0.506 ** | 1 | ||

| INCT | 0.569 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.653 ** | 1 | |

| PB | 0.521 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.512 ** | 1 |

| Estimate | Boot SE | p Value | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| INFT→INCB | Indirect Effect | ||||||

| 0.072 | 0.028 | 0.0101 | 0.025 | 0.139 | 0.022 | 0.133 | |

| Total Effect | |||||||

| 0.469 | 0.087 | 0.0000 | 0.293 | 0.634 | 0.292 | 0.634 | |

| INFT→EXCB | Indirect Effect | ||||||

| 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.4285 | −0.025 | 0.072 | −0.026 | 0.07 | |

| Total Effect | |||||||

| 0.228 | 0.087 | 0.0088 | 0.048 | 0.391 | 0.051 | 0.395 | |

| INCT→INCB | Indirect Effect | ||||||

| 0.051 | 0.023 | 0.0266 | 0.015 | 0.106 | 0.014 | 0.102 | |

| Total Effect | |||||||

| 0.295 | 0.084 | 0.0004 | 0.135 | 0.467 | 0.13 | 0.463 | |

| INCT→EXCB | Indirect Effect | ||||||

| 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.4445 | −0.019 | 0.051 | −0.021 | 0.049 | |

| Total Effect | |||||||

| 0.494 | 0.084 | 0.0000 | 0.335 | 0.669 | 0.332 | 0.666 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Xiong, J. How Governance Tools Facilitate Citizen Co-Production Behavior in Urban Community Micro-Regeneration: Evidence from Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081243

Wu J, Xiong J. How Governance Tools Facilitate Citizen Co-Production Behavior in Urban Community Micro-Regeneration: Evidence from Shanghai. Land. 2022; 11(8):1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081243

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jinpeng, and Jing Xiong. 2022. "How Governance Tools Facilitate Citizen Co-Production Behavior in Urban Community Micro-Regeneration: Evidence from Shanghai" Land 11, no. 8: 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081243

APA StyleWu, J., & Xiong, J. (2022). How Governance Tools Facilitate Citizen Co-Production Behavior in Urban Community Micro-Regeneration: Evidence from Shanghai. Land, 11(8), 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081243