The (In)Ability of a Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts—Lessons Learnt from an Oil Palm Landscape in Myanmar

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context

2.1. Land Governance in Myanmar

2.2. Civil War and the Oil Palm Sector in Tanintharyi Region, Myanmar

2.3. The Background and Story of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

3. Methods

3.1. Analytical Framework

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Design and Governance of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

4.1.1. The Set-Up of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

Management and Representation of Boundaries

- Government group: Regional Minister of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation as the chair of the MSP, Regional Minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation as first vice-chair, Minister of Ethnic Affairs as second vice-chair, and six departments, each sending either their director or an assistant director.

- Civil society organisations (CSO) group: six CSOs were nominated after the CSOs of Tanintharyi Region had jointly discussed who to delegate.

- Companies group: The companies relied on an existing agreement they had among the oil palm companies, saying that two companies per administrative district would represent their group. Accordingly, in total, six companies were nominated to join the MSP.

- Ethnic political organisations (EPO) group: from the two invited organisations, only one agreed to join the MSP.

- OMM Project: The OMM Project was present as the technical advisor regarding the mapping (including foreign experts). A senior Myanmar member of OMM Project—a well-respected and well-connected senior expert in land politics and leader of Myanmar CSO—served as the facilitator of the MSP. The representative of the focal line department (national level) joined with the OMM Project team.

Initialisation and Preparation of the MSP

“We are facing challenges for getting the complete information of basic land use, land cover, and land ownership. These challenges may be problematic for the transparency and accountability when it comes to land problems. Therefore, a spatial data platform is necessary to have access to land-related data and numbers.”[65]

- To guide and supervise the OMM Project’s tasks for investigating the oil palm sector.

- To collaborate with relevant government institutions and organisations to access data, maps, and other information.

- To collect the relevant data and then analyse it. If needed, supervise the field surveys.

- To supervise and guide a technical unit (OMM Project technical staff) so that the unit finishes the tasks according to the timeline for investigating the oil palm sector.

- To supervise the reporting of progresses and work planning.

Secured Resources

Access to Decision-Making

4.1.2. How the Multi-Stakeholder Platform Was Run

Adaptive and Effective Management of the MSP

“It’s very challenging in terms of managing the process, because it is unmanageable.”[66]

Constructive Stakeholder and Relations Management

“We want to benefit our own country and own people. Foreigners want to help Myanmar. But the foreigners have no decision power, only the regional government has. The foreigners will only collect data and operate, and also pay for all expenses.”[67]

Effective Communication and Facilitation

“When, in a process, the most powerful and the least powerful are involved together, target the most powerful to change their mindset first. Without that, collective learning cannot happen.”[68]

“We will base on good will, cooperation, mutual respect, common goals. We will not base our interaction on emotions, but on good intentions. The tone and the language we are going to use must be polite. Otherwise we cannot collaborate.”[69]

“What I would like to say: Since the first meeting, we did not get any information. Nobody gave any information. The staff said that the information letter will pass on. But we have not received it.”[70]

“[…] the Regional Chief Minister said that this issue [on a specific oil palm concession] will be decided in the cabinet meeting this morning. What we want to know is how much the report [created through the MSP] will be used and considered in the decision-making process. The report is finally out, but did the cabinet make a decision on its own? If that is the case, our participation in the leading committee [the MSP] does not make much sense anymore. That is why we would like to know how much of our input and suggestions will be considered and used by the regional government.”[71]

Culture of Reflecting and Learning

Technical Support to the MSP

Collective Action for Systemic Change

4.1.3. The Closing of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

4.2. Effectiveness of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

- In the first interim MSP meeting in October 2016, the Regional Minister for Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation provided an idea of what the regional government would favour having. He stressed that having a spatial data platform is necessary to gain access to land-related data and numbers to tackle land issues.

- In the December 2016 and March 2017 MSP meetings, the terms of reference of the MSP were presented (see Section 4.1.1). The points referred mainly to tasks such as supervising the OMM Project’s mapping activities, collaborating with various stakeholders to help accessing data, contributing to collecting data, supervising the reporting, and so forth. These tasks could probably be summarised as supervising and assisting the OMM Project in doing a land use assessment.

- The Regional Chief Minister communicated her ambition that the land conflicts around oil palm concessions should be addressed and resolved. She mentioned this towards the OMM Project as well as later in her opening speech of the August 2017 MSP meeting. However, she left it open how exactly this should be carried out and what the exact mandate of the MSP would be in this regard.

- In the March 2017 and August 2017 MSP meetings, the OMM Project additionally presented its ideas of what the MSP could aim for over the months and years to come (see Section 4.1.1).

5. Discussion

5.1. Promising and Hindering Factors for the Effectiveness of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

5.1.1. Promising Factors

5.1.2. Hindering Factors

5.1.3. Limitations of the Study

5.2. The (In)Ability of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts

5.3. Novelty of the Study for Scientists and Practitioners

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Design and Governance of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform

| Criteria for Effective Multi-Stakeholder Platforms | Results |

|---|---|

| Set-up a multi-stakeholder platform (MSP) | |

| Management and representation of boundaries | |

| Adequate inclusion and exclusion of stakeholders (and those that they represent) | In the meeting on 8 October 2016, the nomination process was jointly defined. It was agreed on how many seats were reserved per group and how the groups should nominate their representatives. It was also decided that the two ethnic political organisations (EPO), which also claim territorial sovereignty for some or all Tanintharyi Region, were to be invited. After the October meeting, the nominations of representatives per group was completed and a formal launch of the MSP took place on 20 December 2016. The participants of the MSP were as follows:

|

| Communication and engagement strategy for the excluded stakeholders | To our knowledge, there was no communication or engagement strategy for those who were excluded from the MSP. At the beginning, it was once mentioned in the MSP that the representatives of each group would be responsible to communicate back and forth between the MSP and their networks. For example, the present CSOs would inform the non-present CSOs and other contacts from civil society about the discussions and decisions taken inside the MSP and, vice versa, inform the MSP about requests from their networks. Whether this informal communication and feedback mechanism was implemented and used remained unclear, but it seemed quite likely. |

| Matching constituencies and competences of the stakeholder representative (between her/his role in the MSP and in the represented organisation) | Whether the constituencies and competences of the stakeholder representative inside the MSP and in her/his organisation were matching differs depending on the group. The government departments and the CSOs delegated their leaders to the MSP, while the EPO and some of the companies sent lower-level representatives with limited decision-making competences to the MSP. Whether the representatives lobbied for or against the MSP efforts (or neither), once they were back in their organisations, is not known. However, among the government group (especially for the department heads and staff), there was the major challenge of frequent rotations. Accordingly, there were many changes of representatives within the government group. Additionally, the CSOs had to send delegates at times, as the meetings were organised at short notice. Thus, the constituencies and competences of the MSP representatives were partly adequate and partly inconsistent. |

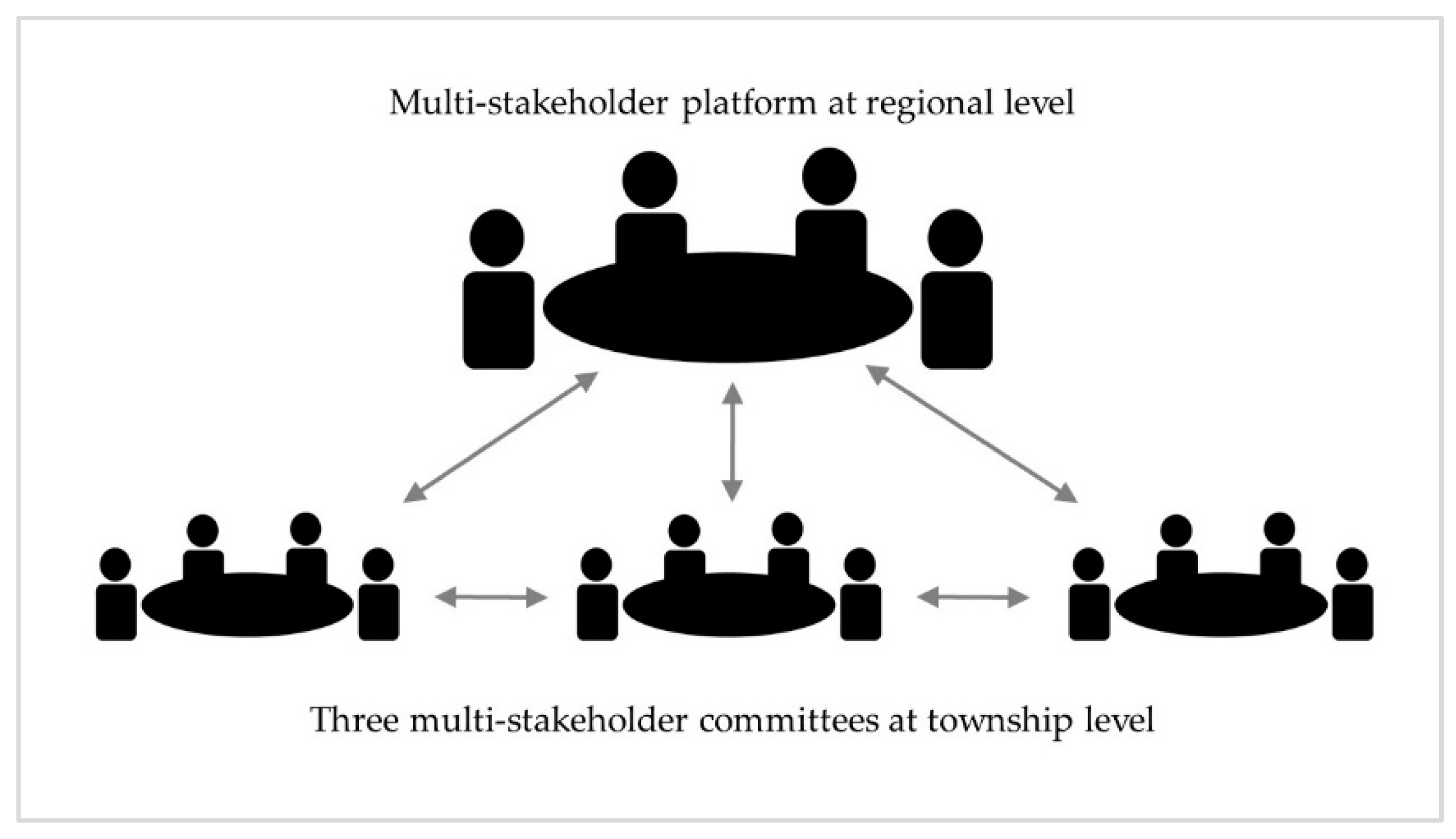

| Linking stakeholders inside and outside the MSP across multiple scales and from different levels (for more effective collaboration and systemic change) | Through the set-up of regional-level as well as township-level committees and the participation of various stakeholder groups, the preconditions for this dimension might have been quite good. An effective collaboration across sectors, representation groups, and administrative levels for a systemic change in the palm oil sector might have become possible. However, as the MSP collapsed rather early, this point cannot be clearly assessed. |

| Initialisation and preparation of a MSP | |

| Situation and conflict analysis (stakeholders, institutions, power, politics, etc.), development of conflict sensitivity approach | Prior to establishing the MSP, the OMM Project made a situation analysis on the various stakeholders in Tanintharyi Region (including a conflict analysis). The conclusion from this analysis was that the context is not favourable for making an MSP. Nevertheless, the Regional Chief Minister and the OMM Project wanted to try it. There was no analysis of the land governance system created for Tanintharyi Region. There was also no conflict sensitivity approach developed for the endeavour. The OMM Project relied on the sensitive guidance by its senior Myanmar members, who were familiar with similar settings. |

| Clarity of reasons for establishing the MSP | When meeting the Regional Chief Minister bilaterally on 22 September 2016, she was quite clear vis-à-vis the OMM Project that her motivation was to tackle land issues related to oil palm concessions and that she would welcome any technical support. When holding the opening speech at the October (2016) meeting with the interim MSP participants, the Regional Minister for Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation also provided quite clear reasons for the establishment of the MSP, however already slightly more specific compared to the September discussions. He said (translated from Myanmar language): “We are facing challenges for getting the complete information of basic land use, land cover, and land ownership. These challenges may be problematic for the transparency and accountability when it comes to land problems. Therefore, a spatial data platform is necessary to have access to land-related data and numbers.” At the formal launch of the MSP in December 2016, however, there was no more mentioning of the overall goal or the reasons for establishing the MSP. Only during the August 2017 meeting did the Regional Chief Minister provide a speech about her motivation why the land issues related to oil palm concessions need to be tackled. Nevertheless, she did not elaborate on how this should be performed through mapping support. Later in the process, not yet during the initialisation, the OMM Project additionally presented its ideas of what the MSP could aim at (see below). |

| Establish interim steering body | In a governmental meeting in September 2016, government representatives and the OMM Project agreed on an interim steering body for the MSP, consistent of representatives from the government, civil society, private sector, and EPOs. This interim steering body met in October 2016 and decided on who to formally elect into the MSP. These elected representatives would then meet in December 2016 in the formal launch of the MSP. It turned out that the formally elected steering body was very similar to the interim steering body of the MSP. |

| Build stakeholder support for the MSP | The stakeholder support for creating the MSP was probably rather ambiguous among the groups and even within the groups. The MSP’s creation seemed to be based on the enthusiasm of the Regional Chief Minister. The level of support by other government representatives could hardly be assessed due to the government protocol of being non-vocal in public. On the CSO side, the support for the MSP creation seemed quite high, or at least the CSOs were interested to see how it evolved. The companies, on the contrary, were mostly quite silent (but not opposing), thus, their level of support remained unidentifiable. The support from the side of the EPO seemed unclear, too, as they remained mostly silent. The level of support by stakeholders, which were not part of the MSP, is unknown to the authors. For all groups, it is unclear whether the representatives joined the MSP for reasons of wanting to contribute to a systemic change or for averting risks in case of non-participation. This might even differ for each individual and it might also be a combination of both. |

| Establish scope and mandate of the MSP, including decision-making competences of the MSP | The decision-making competences, roles, and responsibilities of the groups were not clearly defined at the beginning. It was made clear, however, that the three regional ministers held the leading position of the MSP. It was also communicated clearly that the OMM Project did not have any decision-making competences, but that it served only as technical advisor, enabler, and implementer of and for mapping activities (trainings, field surveys, mapping, etc., including covering all expenses). In the first formal MSP meeting in December 2016 as well as in the second meeting in March 2017, the terms of reference—comparable to a mandate of the MSP—were presented. There was a very short slot for questions and comments on the terms of reference, but no MSP participant raised concerns or questions. The terms of reference were as follows (translated from a slide, which was presented in Myanmar language during the meetings):

|

| Outline process and time horizon of the MSP | Apart from showing the terms of reference and the OMM Project’s ideas on the way forward, there was no presentation or discussion on the entire process and time horizon of the MSP. Usually, the MSP agreed on the next steps at the end of each meeting. |

| Secured resources | |

| Sufficient financial funds | Almost all financial expenses for the MSP and the implementation of activities were covered by the OMM Project (such as travel expenses of MSP participants, in-kind contribution of the OMM Project for its staff, technical equipment for mapping, satellite images, etc.). At the beginning, it seemed that the OMM Project would have enough financial funds for the MSP and all mapping activities. Some MSP participants, however, developed high expectations and extensive requests regarding the mapping and its level of details after the first extensive field survey had been conducted in Yebyu Township. To fulfil these requests, there would not have been enough financial funds, nor enough human resources to complete the tasks within a meaningful timeframe. |

| Sufficient time | The time horizon of the MSP was not pre-defined. Given the envisaged overall duration of the OMM Project, the project could have accompanied the MSP for six or seven years. The bigger time-related challenge might have been the limited availability of the representatives given their partly high ranks and many engagements outside the MSP. |

| Sufficient and the right human resources | In terms of human resources, the picture is more ambiguous. As outlined above, some MSP participants did not have the adequate competences in their home-organisation (e.g., companies). For the technical mapping-related knowledge and skills, most MSP participants were also not fit from the beginning; however, this was also not a prerequisite. In terms of technical advice, the OMM Project brought the right human resources for the mapping. However, there seemed to be a lack of technical expertise on the legal system—as elaborated further below—and probably also on social cohesion and communication. |

| Sufficient and the right equipment | Most equipment for mapping (drones, GPS devices, licenses, satellite images, etc.) was provided by the OMM Project. From all types of resources, the equipment seemed to be the smallest challenge. The OMM Project could mobilise most of it. |

| Access to decision-making | |

| Access to wider (cross-sector) policy-making and governmental top-level decision-making processes | For the government group and for the OMM Project, it was understood—but not formally communicated to the other MSP participants—how the access to decision-making was conceptualised. The MSP was led by three regional ministers and supervised by the Regional Chief Minister. These four high-ranking officials were also members of the regional government cabinet, where political decisions for Tanintharyi Region were discussed. The MSP was supposed to serve as a consultation body for and advice provider to the ministers, who would in turn try to influence the regional government cabinet or even the government representatives from the national level. Moreover, the relevant regional-level governmental departments, such as Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics, Forest Department, or Department of Agriculture were represented in the MSP. Many decisions on mapping and permitting land concessions and investments were made within these departments, mostly at national and regional levels, a typicality of Myanmar’s still centralised and hierarchical government structure. Thus, access to decision-making bodies was given with the structural organisation of the MSP. This, however, was not clearly communicated to the MSP until only August 2017. Despite the rather well-designed access to decision-making, the effective access to the government cabinet and relevant government departments still depended on the willingness and ability of the ministers and department heads to lobby for what was discussed in the MSP. There remained, however, another major challenge. Due to the legal pluralism, there were many different land zones, and for each zone, specific laws, policies, and responsible departments as well as various land-related committees existed. Thus, it remained rather opaque for most MSP participants which body (at which administrative level) to approach for certain decisions. Even most government staff did not understand the entire complexity of Myanmar’s land governance system. Accordingly, access to decision-making was also—in some ways—not given due to the lack of transparency of and clarity on structures and mechanisms in the land governance system. |

| Run an MSP | |

| Adaptive (flexible) and effective management of the MSP | |

| Legitimate and effective management structures | The MSP was managed highly adaptively. The management, however, was also highly complex due to government protocols (of how to obtain meeting permissions, how to send meeting invitations, etc.). For organising one meeting, the focal line department at the national level first needed to ask permission from the Tanintharyi regional government through two parallel channels. Afterwards, the invitations to the MSP participants were sent again through the same channels. It was not allowed for the OMM Project to contact the participants directly. This permission and invitation process lasted between two to four weeks. Accordingly, the invitations usually arrived to the MSP participants at the last minute, which made it sometimes impossible for the delegated representatives to attend themselves. Thus, the management structures and coordination of meetings were legitimate in the given context, however noticeably not sufficiently effective or efficient. |

| Efficient and effective coordination of the meetings | |

| Legitimacy of decisions and processes | The decisions made in the MSP meetings were never a result of voting, a circumstance that can be typical in the Myanmar context. It was usually the facilitator (senior expert) who suggested a decision based on either bilateral discussions with members or based on discussions during the MSP meeting. When the facilitator suggested a decision, usually no one from the MSP made any major objections and his suggestions were silently taken cognizance of. In rare instances, the chairman announced a decision, which the government had already made before the MSP meeting, such as which township to start with the concession mapping. Thus, one could say that decisions and processes were legitimate as there were never any major objections during the meetings. However, it is also possible that MSP participants refrained from making comments due to lacking understanding on the discussion topic or due to feeling outside their comfort zone or field of responsibility. Further, it seems likely that power imbalances in the room, government protocol, and cultural codex of behaviour did not allow for MSP members to raise any major objections to either high-ranking government officials or the senior facilitator. |

| Adaptive capacity (flexibility) in planning and management | The action plans discussed during the MSP meetings were usually encompassing a timeline from the current meeting until the next meeting. Some steps were elaborated rather in detail, others were left quite open. Usually, the outlook on future actions had to be considerably revised after each meeting. It seemed as if the OMM Project and the MSP were on a very explorative path, as no such multi-stakeholder process had taken place before in this regional context and as the complexity of reality (around oil palm concessions and land governance more in general) was very high and almost unknown to most members. |

| Detailed but adaptive action plans | |

| Commonly agreed-on strategies for change | Despite—or due to—the highly dynamic and complex context, the MSP did not discuss or agree on strategies for change, success criteria, and indicators or monitoring mechanisms for observing progress. |

| Definition of success criteria and indicators | |

| Development and implementation of monitoring mechanisms | |

| Revision of progress, reflection on lessons learnt and feedbacks | During the August 2017 meeting, there was some reflection on lessons learnt and on feedback provided by the MSP participants from March 2017. Thanks to this reflection, the MSP group elaborated convincing plans for the months to follow (see above), which were unfortunately never realised due to its falling apart. |

| Constructive stakeholder and relations management | |

| Trust among the participants | At the very beginning of the MSP in October 2016 (the interim MSP meeting), trust was greatly lacking, especially on the CSO side, but probably also among the other groups. The CSOs strongly refused to enter the same room as the company representatives. Only thanks to an immediate conflict intervention and moderation in the hallway by the MSP facilitator did the CSOs finally hesitantly enter into the room, where the government and company representatives were waiting. After the meeting, however, the CSOs also seemed very committed to continue the collaboration, as it appeared to be a unique chance for tackling the entrenched land conflicts around oil palm concessions. This seemed to be a considerable progress given the decades-long conflict-affected history of Tanintharyi Region. |

| Understanding among the participants (including critical self-reflection, acknowledgement of problems and expectations of participants, overcoming prejudice, etc.) | The understanding among the participants also seemed to improve slightly thanks to some problem story-telling of all groups. However, none of the participants seemed to critically self-reflect or alter their own respective understandings very much. |

| Definition of roles, responsibilities, and decision-making competences of participants/the groups | Only in August 2017 were the decision-making competences of the MSP clearly communicated to the members, saying that they would be limited to formulating recommendations and requests to the regional government. They might have been clear to the government and the OMM Project, however most likely not to the other groups. With the exception of the OMM Project’s role and responsibility as an outsider to Tanintharyi Region, the roles and responsibilities of all other groups have also never been specifically discussed. The CSOs repetitively pointed out this deficit, however the MSP did not react to it. The lacking definition of roles, responsibilities, and decision-making competences led to an increasing frustration on the side of CSOs and the OMM Project. |

| Consensus among participants (vision, expectations, rules of the game, etc.) | Similar to the fact that decisions were rather silently taken cognizance of, consensus among the participants (on processes, rules of the game, vision of the MSP, etc.) was also not explicitly fostered. The facilitator repetitively stressed that the mutual communication should be respectful to be successful as an MSP, and everyone seemed to agree. The focus of consensus-finding was usually on the next steps. Other than this, there was no explicit discussion on expectations, vision, processes, structures, etc. Maybe this was left open on purpose, given the possibility that a joint problem-framing and consensus-finding on overall goals might have been challenging in this fragile MSP setting. |

| Strong stakeholder ownership and commitment, collaborative leadership | The ownership and commitment among the stakeholders differed among the groups and even within the groups and rather depended on the individual representatives. The ownership and commitment of the government group seemed quite high at the beginning, however, the willingness to consult the MSP decreased drastically with rising challenges. The government group was by no means homogeneous. The ownership, commitment, and the leadership seemed to heavily depend on the individuals joining the MSP meeting, which changed often due to the many engagements of the government staff and the frequent position rotations. Nevertheless, it was observable that out of the three most relevant government departments, two were rather responsive and constructive, while one was noticeably passive or even slowed down the process outside the MSP meetings, a behaviour that can be understood in the Myanmar context as a sign of non-interest, uncertainty, or even opposition. On the CSO side, ownership and commitment seemed quite high at some points in time (visible through punctually lots of feedback, requests, and questions, sending their leaders to the meetings, etc.). At the same time, the CSOs sometimes appeared to be at the brink of quitting their membership in the MSP. After the challenges had begun in December 2017 and the MSP did not get the chance to meet again, the CSOs repetitively threatened to officially leave the MSP in case the MSP’s role in the entire oil palm concession politics would not be clarified and formalised. The companies, on the contrary, were mostly quite silent (but not opposing). Some of the companies did not send their top leaders, but lower-level representatives with less decision-making competences, and thus, most likely also less discussion-making competences. While few company representatives openly communicated their interest and support in resolving land conflicts, as conflicts are hindering for business, others never uttered any statements. Thus, the ownership and commitment among the companies might have been rather diverse. Noteworthy, most companies cooperated extensively on site, whenever mapping activities took place on their concession areas. The ownership and commitment from the side of the EPO seemed unclear from beginning to end. They never sent high-ranking delegates, nor did they participate in discussions. |

| Equity and inclusiveness | There were many efforts by the facilitator of being inclusive and treating everyone equally. Only the companies were sometimes (maybe unconsciously) neglected in welcoming speeches or excluded in discussions. The companies, for their part, were often very silent. |

| Dealing with influential stakeholders inside the MSP | The facilitator had a very good systemic understanding and feeling for detecting the influential stakeholders. He was also familiar with the complex hierarchies inside the government. As well as acknowledging the formal power structures, he also considered the informally influential individuals. He respected the power setting and dealt with the influential stakeholders by proactively providing them space for talking, asking them specific questions (most likely to foster their learning effect, increasing their willingness to collaborate, and/or to test the feasibility of an idea), or by making sure they had good seats. |

| Effective conflict management | Except for the vocal conflict incident in October 2016 in the hallway, there was no incident of a conflict noticeably escalating during an MSP meeting. There were most likely several tensions occurring. The setting, however, was too formal for conflict escalation. Accordingly, the facilitator needed sensitivity for detecting tensions or dissatisfaction. Whenever he sensed such a situation and the concerned participants were rather influential, he approached the participant(s) during a break or after a meeting to pacify the emotions. Later, when there were no MSP meetings taking place anymore, tensions on the CSO side towards the OMM Project rose. As described above, the CSOs requested a clear definition of the MSP’s role in the politics regarding oil palm concessions. This conflict was never resolved. Due to the limited effectiveness of the MSP, the OMM Project also faced internal disagreements on the way forward, which it did not manage to resolve timely. |

| Joint activities of the participants | Apart from lunches and tea breaks, where most groups sat among themselves, there were no joint activities of the MSP members. There were also no other social activities during the MSP meetings. At the township level, however, there were joint trainings for the committee members (drone operation trainings, etc.) and field surveys. These activities helped a lot to overcome barriers of communication and maybe even prejudice within the committee. Even though the focal unit of this study is not at the township level, this illustrates that joint social activities can indeed have a positive impact on the atmosphere among the MSP participants. However, probably, the setting at the regional level was too formal and the conflict histories between the stakeholders too entrenched. |

| Effective communication and facilitation | |

| Constructive facilitation during MSP meetings, including powerful questions of the facilitator(s) | The facilitation of this MSP was of considerable importance. The interim MSP meeting in October 2016 proved that a facilitator was needed, who knew how to bring groups to one table, which had been in conflict for several decades. The facilitator of this MSP was a senior and well-connected land and facilitation expert. He was used to even higher-level and politically sensitive land-related MSPs. Most likely, it was only thanks to him that this MSP survived the first get-together in October 2016, which was the most critical. In all meetings to follow, the facilitator usually sensed the expressed but also the unexpressed feelings in the room. Noticeable, however, he paid special attention and politeness to the more influential persons in the room, less so to the less relevant stakeholders. In an interview, he confirmed that he would especially focus on the positive learning of the more influential persons (see also above), as he believed that the MSP would only make progress if the most influential supported it. The facilitator also very strategically led the discussions by providing summaries of speeches, asking powerful questions in a certain direction, highlighting the main points of the meeting from his perspective, or by presenting suggestions of how the MSP could decide on an issue. It remained unclear whether he did this strategic steering of discussions for influencing the outcome of the MSP meetings or for efficiently moving on during a meeting with many agenda points (or other reasons). |

| Active (and if possible, equal) participation in communication of all participants | Noticeably often, the chairmen and the facilitator motivated all participants to be active, open, and polite in their communication and invited everyone to equally participate. In the first formal MSP meeting in December 2016, the CSO, companies, and EPO groups were conspicuously quiet. It was later found out that the CSO representatives did not yet dare to speak in this setting, as they had no experience with multi-stakeholder meetings of this dimension and composition. In the later MSP meetings, the CSOs were much more active in communication and seemed well-prepared. The companies and the EPO groups continued to be rather quiet in the formal format. Additionally, the chairmen were conspicuously quiet. The facilitator invited them several times to express their standpoint on certain topics to get a feeling for their priorities and for the feasibility of ideas. |

| More dialogue, less debate | The discussions were usually held neither in a dialogue format nor as debates. Mostly, the communication was limited to either presentations or question-and-answer slots after a presentation. As noted, the setting was probably too formal and the meetings too short (usually two to three hours) to let dialogue develop. Only during the second day of the August 2017 meeting, when group works were held, did dialogues happen. Most likely, this was due to the much more informal sitting order, with only chairs in a small circle and without the chairmen being present, instead of the normal sitting order as can be found in formal state meetings (where tables form a U-shape, and each participant has a microphone on the table). |

| Non-violent communication | Even though the different groups experienced decades of entrenched land conflicts and war, at most times, the communication in the MSP meetings was non-violent, with rare incidents of indirect shaming and blaming. |

| Active listening of all participants | It also seemed that most MSP participants listened actively whenever someone spoke. The active listening was noticeably the case for the CSOs, the companies, and the OMM Project. This could be noted due to the high responsiveness of the CSOs and the OMM Project and the active note-taking of the company representatives. Within the government group, the degree of active listening seemed diverse and seemed to depend on the individual. On the EPO side, it is hard to tell how actively the representatives were listening. |

| Joint language and communication style | In terms of joint language and communication style, the most noticeable difference was between the stakeholders with mapping experience (OMM Project and some government representatives) and the rest of the MSP participants. This was evident in most MSP meetings, as concession mapping was the component which pulled everyone into the MSP, even though the interests behind the mapping were different among the MSP participants. While the stakeholders with mapping experience used many more technical terms in their language and tried to focus on solving technical mapping issues (e.g., which reference system to use in GIS, whether to work with satellite images or drones), the other participants focused on their more context-related problems and interests. The CSOs, for example, wanted to integrate the old village locations in the maps to prove where the refugees originally came from. The companies requested that also unplanted land should be included in the concession maps, if it was left unplanted on purpose such as for water catchment, milling, housing, protection against soil erosion on steep slopes, etc. As there were almost no dialogues happening (see above) and the MSP only existed for less than a year, the MSP never reached a joint language. This might be rooted in the problem that the MSP did not have a joint problem-framing and vision, and/or that the MSP members did not know or express what data they needed to support different kinds of decision-making processes. Accordingly, the presentation of technical mapping results was probably disconnected from the needs or interests of the MSP members. |

| Timely and transparent communication to everyone (during and between meetings) | Timely and transparent communication to everyone seemed to be a major challenge, especially between the meetings—less so during the meetings. At almost each MSP meeting, some participants complained about late invitations (see above) and the lack of sharing meeting minutes with everyone. Especially after the last MSP meeting in August 2017, there was a major lack of communication among the MSP participants. Additionally, the OMM Project failed in informing timely and transparently about the steps it undertook in the meantime. It is assumed that this omission was due to two reasons. Firstly, it was not allowed for the OMM Project to communicate directly with the MSP participants. All communication had to go through governmental channels (see above). Secondly, the OMM Project faced several challenges itself (internal disagreements, lack of access to government data, etc., see above) and felt uncomfortable to inform MSP participants about their challenges. The OMM Project decided to wait with communication and a next MSP meeting invitation until there was visible progress on the concession mapping activities. Besides the OMM Project, also the regional government did not communicate timely and transparently with the MSP. As outlined in Section 2.3, the regional government undertook some serious actions against oil palm concessions without consulting or informing the MSP. This lack of communication was looked on with disquiet or even resentment by some MSP groups. |

| Effective and transparent communication with non-participants and the public | Whether the communication with non-MSP participants and the public was effective and transparent is impossible to tell. It is assumed that each MSP group communicated through their own channels to spread information from the MSP meetings or to bring feedback back into the MSP. It is certain that there were no official communiqués of the MSP, which would have been shared with, e.g., media or other stakeholders. |

| Culture of reflecting and learning | |

| Provision of time for learning and reflecting | Apart from the August 2017 meeting, there was not much conscious reflecting and learning, as time was always short and the setting formal. The second day of the August 2017 meeting was dedicated to group work, including reflecting on lessons learnt and the way forward. As it seemed, this was a successful exercise with promising outputs for the continuance of the MSP (see Section 2.3). Unfortunately, this was the last time the MSP came together. The OMM Project also needed to learn and reflect. However, the persisting internal disagreements on the way forward proved that this internal learning and self-reflection process unfortunately did not take place sufficiently or probably not with the most useful methods. |

| Use of supportive methods and approaches | |

| Effective collective reflecting and learning (on successes and failures, (dis)agreements, equality, norms, values, relationships, individual social-emotional competences, etc.) | |

| Technical support (expertise) to the MSP | |

| Sufficient and the right technical advice/support | From the beginning, it was clear that the MSP would need technical support regarding mapping (besides other expertise). The OMM Project could provide the right and sufficient technical support in this regard. After the first extensive field survey of an oil palm concession in Yebyu Township, however, it became evident that the MSP was also in need of legal advice regarding land conflict resolution and rightful land use and ownership. Questions such as what to do with overgrown and neglected plantations, how many plants per acre (Myanmar unit of measurement of space) needed to be planted by the company to fulfil the contract, what to do in case of forced displacements or war-related fleeing of entire villages, etc., needed clarification by experts. Additionally, there was a need for expert support regarding understanding the land governance system of Myanmar. It was unclear what would happen to the revoked land, which department or which committee at which level would have the decision-making competences to resolve disputes, etc. The MSP members themselves stated that they lacked the understanding of these complex and—to some extent—nontransparent land governance mechanisms. The lack of such expert support was clearly identified by everyone in the August 2017 meeting. Afterwards, the OMM Project tried to mobilise respective technical support, however without much effect. It seemed difficult to find such experts, and the MSP did not meet anymore afterwards. It is also possible that the OMM Project could have benefitted from an expert in communication, facilitation, and conflict management from the field of peace- and state-building to advise the OMM Project on its challenging role and internal learning. |

| Collective action for systemic change | |

| Willingness to change | The Regional Chief Minister seemed overly enthusiastic to resolve land issues related to oil palm concessions. Similar were some individual statements of other government representatives (but not all). Additionally, the CSOs were willing to contribute to this systemic change. The companies stated that they also suffered from unclear legal conditions, unclear concession boundaries, and land use conflicts with villagers. During the field surveys, the companies mostly appeared collaborative and supportive. These statements and observations indicate interest of—at least several if not of all—companies to address these land issues. The perceptions of how exactly the addressing of land issues should be carried out remained presumably different among the groups, even though it was not explicitly discussed. From the EPO’s side, little is known for this point. |

| Embrace complexity and a change of the system | The complexity of the system and the change thereof was a major issue. The OMM Project (including the facilitator) often reminded the MSP members of the complexity of mapping and that mapping is not free from being political and therefore needs to be performed cautiously. The OMM Project also highlighted that “giving land back” to the local people is not as simple as it might seem, and that it can easily lead to new conflicts if not carried out in a well-considered way. It might also have appeared disillusioning to some MSP members that the land governance system was highly complex, favouring mostly the elite, and could not be changed within a short time. |

| Development of skills and capacities for action | Due to this complexity, the unclear mandate, problem-framing, and goal of the MSP, the early falling apart of the MSP, and probably also the lack of technical support in the legal domain, there was not sufficient development of skills and capacities for all MSP members. |

| Collaborative action outside the MSP meetings, including identification of actions, responsibilities for actions, and management of successful implementation | The regional and national government continued taking serious actions on land governance in the oil palm sector (see Section 2.3). The governmental stakeholders highlighted that the support by the OMM Project (for the MSP) was very useful to them, as it enabled them to access maps and better understand the challenges around the concessions in general. Hence, there were some actions indirectly resulting from the MSP, which had a strong impact on the system (e.g., revoking of permits). These actions, though, were not collectively taken within the MSP as originally intended and they also did not transform institutions as much as was probably hoped for by the CSOs or the OMM Project. |

| Transformation of institutions | |

| Close an MSP | |

| Closure of an MSP | |

| Development and adaptation of an exit strategy (e.g., how a continuation after the MSP, after external support, or after the facilitation, etc., would look) | There was no exit strategy in place. |

| Revision of the MSP process and draw lessons learnt (e.g., expectations, goals, outcomes, strengths, weaknesses, success, failure, monitoring) | As the MSP was never formally closed, there was also no opportunity for a joint reflection on or review of the goals, outputs, and outcomes, nor a reflection on expectations of MSP members and non-members. |

| Official closure of the MSP (e.g., closing event, final reporting, final communication to the public) | There was neither a closing event nor a final reporting or communication to the MSP members or the public. |

References

- Pacheco, P.; Gynch, S.; Dermawan, A.; Komarudin, H.; Okarda, B. The Palm Oil Global Value Chain: Implications for Economic Growth and Social and Environmental Sustainability; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, J.; Ghazoul, J.; Nelson, P.; Klintuni Boedhihartono, A. Oil Palm Expansion Transforms Tropical Landscapes and Livelihoods. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Pacheco, P. Expansion of Oil Palm Plantations in Indonesia’s Frontier: Problems of Externalities and the Future of Local and Indigenous Communities. Land 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, L.; Moorthy, R. A Review of Key Sustainability Issues in Malaysian Palm Oil Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffartzik, A.; Brad, A.; Pichler, M.; Plank, C. At a Distance from the Territory: Distal Drivers in the (Re)Territorialization of Oil Palm Plantations in Indonesia. In Land Use Competition: Ecological, Economic and Social Perspectives; Niewöhner, J., Bruns, A., Hostert, P., Krueger, T., Nielsen, J.Ø., Haberl, H., Lauk, C., Lutz, J., Müller, D., Eds.; Human-Environment Interactions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 41–57. ISBN 978-3-319-33628-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brad, A.; Schaffartzik, A.; Pichler, M.; Plank, C. Contested Territorialization and Biophysical Expansion of Oil Palm Plantations in Indonesia. Geoforum 2015, 64, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.M.; Metz, F.; Fischer, M.; Schneider, F.; Myint, W.; Messerli, P. The Making of Land Use Decisions, War, and State. J. Land Use Sci. 2021, 16, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietilainen, E.P.; Otero, G. Power and Dispossession in the Neoliberal Food Regime: Oil Palm Expansion in Guatemala. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 1142–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. After the Land Grab: Infrastructural Violence and the “Mafia System” in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Plantation Zones. Geoforum 2018, 96, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkapaw; TRIP NET; Southern Youth; Candle Light; Khaing Myae Thitsar; Myeik Lawyer Network; Dawei Development Association. Green Desert: Communities in Tanintharyi Renounce the MSPP Oil Palm Concession. 2016, p. 56. Available online: https://www.farmlandgrab.org/post/view/26866 (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Lund, C. Predatory Peace. Dispossession at Aceh’s Oil Palm Frontier. J. Peasant Stud. 2018, 45, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.M.; Schneider, F.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Oberlack, C.; Myint, W.; Messerli, P. Whose Agency Counts in Land Use Decision-Making in Myanmar? A Comparative Analysis of Three Cases in Tanintharyi Region. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, U.S.; Diepart, J.-C.; Moe, U.H.; Allaverdian, C. Large-Scale Land Acquisitions for Agricultural Development in Myanmar: A Review of Past and Current Processes; MRLG Thematic Study Series; Mekong Region Land Governance: Vientiane, Laos, 2018; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, I.G.; Le Billon, P. Landscapes of Political Memories: War Legacies and Land Negotiations in Laos. Political Geogr. 2012, 31, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepart, J.-C.; Dupuis, D. The Peasants in Turmoil: Khmer Rouge, State Formation and the Control of Land in Northwest Cambodia. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, J.; Williams, R.C. Lessons Learned in Land Tenure and Natural Resource Management in Post-Conflict Societies. In Land and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding; Unruh, J., Williams, R.C., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 553–594. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Castañeda, L. What Kind of Space? Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives and the Protection of Land Rights. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2015, 22, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bächtold, S.; Bastide, J.; Lundsgaard-Hansen, L. Assembling Drones, Activists and Oil Palms: Implications of a Multi-Stakeholder Land Platform for State Formation in Myanmar. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faysse, N. Troubles on the Way: An Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Multi-Stakeholder Platforms. Nat. Resour. Forum 2006, 30, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.F. More Sustainable Participation? Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Integrated Catchment Management. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2006, 22, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento Barletti, J.P.; Larson, A.M.; Hewlett, C.; Delgado, D. Designing for Engagement: A Realist Synthesis Review of How Context Affects the Outcomes of Multi-Stakeholder Forums on Land Use and/or Land-Use Change. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B.; Burnley, C.; Mugisha, S.; Madzudzo, E.; Oeur, I.; Mam, K.; Rüttinger, L.; Chilufya, L.; Adriázola, P. Facilitating Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue to Manage Natural Resource Competition: A Synthesis of Lessons from Uganda, Zambia, and Cambodia. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steins, N.A.; Edwards, V.M. Platforms for Collective Action in Multiple-Use Common-Pool Resources. Agric. Hum. Values 1999, 16, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, H.; Woodhill, J.; Hemmati, M.; Verhoosel, K.; van Vugt, S. The MSP Guide: How to Design and Facilitate Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-85339-965-7. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.R.A.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What Is Social Learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. Available online: https://ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/resp1/ (accessed on 19 March 2019). [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Olsson, P.; Iii, F.S.C.; Holling, C.S. Resilience, Experimentation, and Scale Mismatches in Social-Ecological Landscapes. Landsc. Ecol 2012, 28, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational Multistakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Conditions for Success. Ambio 2016, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Schulman, S. Myanmar’s Top-Down Transition: Challenges for Civil Society. IDS Bull. 2019, 50, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, S. Are the Odds of Justice “Stacked” Against Them? Challenges and Opportunities for Securing Land Claims by Smallholder Farmers in Myanmar. Crit. Asian Stud. 2016, 48, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Feurer, M.; Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.M.; Myint, W.; Nuam, C.D.; Nydegger, K.; Oberlack, C.; Tun, N.N.; Zähringer, J.G.; Tun, A.M.; et al. Sustainable Development Under Competing Claims on Land: Three Pathways Between Land-Use Changes, Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurrah, N.; Hirsch, P.; Woods, K. The Political Economy of Land Governance in Myanmar; Mekong Region Land Governance: Vientiane, Laos, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, J.; Kramer, T.; Woods, K. Developing Disparity—Regional Investment in Burma’s Borderlands; Transnational Institute (TNI), Burma Center Netherlands (BCN): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, K. The Political Ecology of Rubber Production in Myanmar: An Overview; Global Witness: Yangon, Myanmar, 2012; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, K. Commercial Agriculture Expansion in Myanmar: Links to Deforestation, Conversion Timber, and Land Conflicts; Forest Trends Report Series; Forest Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney-Lazar, M.; Suhardiman, D.; Hunt, G. The Spatial Politics of Land Policy Reform in Myanmar and Laos. J. Peasant Stud. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, T. Ethnic Conflict and Lands Rights in Myanmar. Soc. Res. Int. Q. 2015, 82, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Transition. J. Contemp. Asia 2014, 44, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, A. Displacement and Dispossession: Forced Migration and Land Rights in Burma; COHRE Country Report; The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Displacement Solutions. Bridging the HLP Gap—The Need to Effectively Address Housing, Land and Property Rights During Peace Negotiations and in the Context of Refugee/IDP Return; Displacement Solutions and Federal Department of Foreign Affairs Switzerland: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- KHRG. “Do Not Trespass”: Land Confiscations by Armed Actors in Southeast Myanmar; Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG): Myanmar, 2019; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Transnational Institute. Re-Asserting Control: Voluntary Return, Restitution and the Right to Land for IDPs and Refugees in Myanmar; Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G.; Oswald, P. Tanintharyi Regional Oil Palm Assessment: Macro-Level Overview of Land Use in the Oil Palm Sector; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, K.M. Green Territoriality: Conservation as State Territorialization in a Resource Frontier. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, K.M.; Wang, P.; Sexton, J.O.; Leimgruber, P.; Wong, J.; Huang, Q. Integrating Pixels, People, and Political Economy to Understand the Role of Armed Conflict and Geopolitics in Driving Deforestation: The Case of Myanmar. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberndorf, R.B. Legal Review of Recently Enacted Farmland Law and Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law; Food Security Working Group: Yangon, Myanmar, 2012; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baskett, J.P.C. Myanmar Oil Palm Plantations: A Productivity and Sustainability Review; Tanintharyi Conservation Programme, a Joint Initiative of Fauna & Flora International and the Myanmar Forest Department: Yangon, Myanmar, 2016; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- De Alban, J.D.T.; Prescott, G.W.; Woods, K.M.; Jamaludin, J.; Latt, K.T.; Lim, C.L.; Maung, A.C.; Webb, E.L. Integrating Analytical Frameworks to Investigate Land-Cover Regime Shifts in Dynamic Landscapes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehringer, J.G.; Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.; Thein, T.T.; Llopis, J.C.; Tun, N.N.; Myint, W.; Schneider, F. The Cash Crop Boom in Southern Myanmar: Tracing Land Use Regime Shifts through Participatory Mapping. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Heinimann, A.; Naing, S.M.; Blaser, J.; Celio, E. Quantifying Local Ecosystem Service Outcomes by Modelling Their Supply, Demand and Flow in Myanmar’s Forest Frontier Landscape. J. Land Use Sci. 2021, 16, 55–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHRG. Losing Ground: Land Conflicts and Collective Action In Eastern Myanmar; Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG): Myanmar, 2013; pp. 1–92. Available online: https://www.khrg.org/2013/03/losing-ground-land-conflicts-and-collective-action-eastern-myanmar (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- KHRG. “Development Without Us”: Village Agency and Land Confiscations in Southeast Myanmar; Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG): Myanmar, 2018; pp. 1–124. Available online: https://www.khrg.org/2018/08/%E2%80%98development-without-us%E2%80%99-village-agency-and-land-confiscations-southeast-myanmar (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- OneMap Myanmar. What Is OneMap? OneMap Myanmar: Yangon, Myanmar, 2018; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- OneMap Myanmar. Project Overview Factsheet; Centre for Development and Environment: Yangon, Myanmar, 2020; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nyein, Z. Over 100,000 Acres of Idle Land in Taninthayi without Oil Palm Cultivations to Be Confiscated. Eleven Myanmar, 31 August 2018. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/news/21368(accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Craps, M.; Dewulf, E.; Mostert, E.; Tabara, D.; Taillieu, T. Social Learning and Water Resources Management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.-L.; Giger, M. CDE Experience with Multi-Stakeholder Platforms; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2021; unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, M. Multi-Stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability: Beyond Deadlock and Conflict; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-84977-203-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, S.; Chiddambaranathan, M.; Escobar, C.; Wiesmann, U. “It Was Hard to Come to Mutual Understanding …”—The Multidimensionality of Social Learning Processes Concerned with Sustainable Natural Resource Use in India, Africa and Latin America. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2006, 19, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.; Parker, J. Learning in Support of Governance: Theories, Methods, and a Framework to Assess How Bridging Organizations Contribute to Adaptive Resource Governance. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, G. How Participatory Methods Facilitate Social Learning in Natural Resource Management: An Exploration of Group Interaction Using Interdisciplinary Syntheses and Agent-Based Modeling; University of Osnabrück: Osnabrück, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beers, P.J.; Mierlo, B.; Hoes, A.-C. Toward an Integrative Perspective on Social Learning in System Innovation Initiatives. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Plummer, R.; Haug, C.; Huitema, D. Learning Effects of Interactive Decision-Making Processes for Climate Change Adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke-de Kruijf, J.; Bressers, H.; Augustijn, D.C.M. How Social Learning Influences Further Collaboration: Experiences from an International Collaborative Water Project. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Effectiveness of International Environmental Regimes: Existing Knowledge, Cutting-Edge Themes, and Research Strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19853–19860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. MSP interim meeting, Dawei, Myanmar. October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. OMM Project member. Qualitative Interview, Yangon, Myanmar. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. MSP meeting, Dawei, Myanmar. 20 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Facilitator of the MSP. Qualitative Interview, Yangon, Myanmar. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Facilitator of the MSP. MSP meeting, Dawei, Myanmar. December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous; Anonymous. MSP meeting, Dawei, Myanmar. March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous; Anonymous. MSP meeting, Dawei, Myanmar. August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, M.; Alvarez, C.; Huth, M. Land Stakeholder Analysis: Governance Structures and Actors in Burma; USAID and Land Core Group: Burlington, Canada, 2017.

| When | Major Events | MSP Involved |

|---|---|---|

| 8 October 2016 | Interim MSP meeting to agree on a nomination process for the formal MSP. | |

| 20 December 2016 | Formal launch of the MSP, with representatives from the government, companies, civil society organisations (CSO), and one of the ethnic political organisations (EPO). Main decision/request (by government group): start with mapping oil palm concessions in Yebyu Township. | |

| February to March 2017 | Detailed mapping of oil palm concessions in Yebyu Township by the OMM Project: collection and digitalisation of concession permits, drone mapping of planted area. | yes |

| 16 March 2017 | Formal MSP meeting to present and discuss insights from concession mapping in Yebyu Township. Outputs: less feedback on mapping procedure and maps, but request to focus more on the plot-level documentation of land conflicts (through mapping). | |

| April to August 2017 | Formation of a Yebyu Township multi-stakeholder committee to steer and implement the forthcoming field surveys (plot-level analysis and mapping). Several meetings of the Yebyu Township committee and intense field surveys around one concession took place. Output: very detailed report on one concession, including maps and recommendations for further technical and political actions (published by the Yebyu Township committee with strong support of the OMM Project). | yes |

| April to August 2017 | Formation of identical multi-stakeholder committees in Bokpyin and Tanintharyi Townships. No actions taken yet. | yes |

| April to June 2017 | The Regional Chief Minister requested the OMM Project directly to map five concessions under National Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC) agreements. The MSP was not consulted. After being hesitant, the OMM Project mapped the concessions based on satellite images and the formal permits. | no |

| 15 and 16 August 2017 | Cross-level MSP meeting (regional-level MSP and all three township committees) to present and discuss on: (1) the detailed concession report from the Yebyu Township committee, (2) the mapping results of the big MIC concessions, and (3) plans of the regional-level MSP and each township committee for the coming six months. Outputs: (1) heated discussion but no decisions on the detailed report by the Yebyu committee, and recommendation by the OMM Project to do a regional assessment (mapping and analysis) of all concessions in Tanintharyi Region on a broader scale, no more plot-by-plot mapping, (2) feedback that the MIC concession maps were wrong, without further discussion, and (3) jointly agreed action plans for the coming six months. | |

| October to December 2017 | The national MIC group spontaneously visited the five oil palm concessions under MIC agreements to review the situation on the ground, with the intention to revoke permits for unused concession land. The OMM Project was invited to join and assisted with mapping. The report by MIC (based on the field visit) was shared with the regional government for input and feedback. The MSP was neither consulted nor informed. | no |

| December 2017 | Considerable encroachment by villagers on the surveyed oil palm concession in Yebyu Township as an indirect consequence of the detailed report (as some form of vigilantism). | no |

| January 2018 | Reminder by national-level government to Yebyu Township (after having read the detailed report from the first concession), stressing that township- and regional-level governments cannot simply revoke land from concessions and distribute it to villagers without consulting the national level. | no |

| December 2017 to early 2018 | Meetings of the township-level committees: The Tanintharyi committee was very poorly attended, while the Bokpyin committee was well-attended but lacked leadership and orientation. No further actions taken. The two committees never met again. The Yebyu committee decided to make a similar mapping of one more concession. When presenting the maps to the company, government representatives, the EPO, and villagers, the discussion escalated due to the longstanding land conflict history and the villagers demonstratively left the room. The Yebyu committee never met again. Result: all township-level committees fell apart. | yes |

| Early 2018 | Some CSO representatives informed that they would officially leave the MSP if no further actions with or consultations of the MSP would be conducted. Nevertheless, the non-consultation continued. | no |

| Early 2018 onwards | Internal challenges inside the OMM Project (personnel, internal disagreements, time availability, etc.) as well as lacking access for the OMM Project by various government departments to concession contracts, which would have been necessary to start the regional assessment proposed in the August 2017 MSP meeting. The mapping was considerably delayed. The MSP was neither consulted nor informed. | no |

| Early 2018 onwards | The regional government takes further serious actions regarding oil palm concessions: It decided not to grant any other oil palm concessions anymore, cancelled pending permit requests, cancelled old rubber and oil palm concession permits issued under the military regimes, which had not been implemented, and started a survey to explore which land could further be taken back from the concessions. The MSP and OMM Project were neither consulted nor informed. | no |

| June to September 2018 | Extensive regional assessment by the OMM Project of oil palm concessions based on site visits, some satellite images, scale mapping, and interviews (in collaboration with companies and government departments) to prepare a regional overview of the oil palm sector. Output: extensive report, publicly available (published in 2020). | no |

| June 2018 | Urgent request by regional government departments to the OMM Project to visualise land areas (on maps), which can be revoked from concessions. These maps were intended to be used when discussing with the national MIC group. After being hesitant, the OMM Project produced such maps but stressed clearly that these maps should not form the basis of any decisions. The OMM Project did not know how these maps were used further. | no |

| August 2018 | National MIC announces to confiscate over 40,000 ha from the unproductive MIC concessions and invites domestic and foreign investors to apply for these lands [54]. | no |

| Phase | Dimensions | Criteria for Effective MSPs | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set-up a multi-stakeholder platform (MSP) | Management and representation of boundaries |

| [21,22,55] |

| Initialisation and preparation of an MSP |

| [22,24,56] | |

| Secured resources |

| [21,24] | |

| Access to decision-making |

| [21,57] | |

| Run an MSP | Adaptive (flexible) and effective management of the MSP |

| [24,55,57] |

| Constructive stakeholder and relations management |

| [21,24,25,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] | |

| Effective communication and facilitation |

| [21,24,55,56,57,58] | |

| Culture of reflecting and learning |

| [21,24,25,55,57,58,59,61,62,63] | |

| Technical support (expertise) to the MSP |

| [56] | |

| Collective action for systemic change |

| [21,24] | |

| Close an MSP | Closure of an MSP |

| [24,56] |

| Method | When | With Whom | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writing or accessing meeting minutes of the MSP meetings | October 2016, December 2016, March 2017, August 2017 (n = 4) | All MSP participants | October 2016: minutes written by focal line department All other meetings: minutes written by first author and Myanmar research colleague |

| Participatory observation in MSP meetings | December 2016 (n = 1; half day) | All MSP participants | First author and Myanmar research colleague participated, taking notes of observations (e.g., sitting order, atmosphere among participants, etc.), taking pictures, and writing meeting minutes (see above) |

| March 2017 (n = 1; half day) | All MSP participants | Same as March 2017 | |

| August 2017 (n = 1; 2 full days) | All MSP participants, also township-level MSP participants | None of the authors could attend. The Myanmar research colleague joined the MSP meeting and documented it with videos, pictures, note taking of observations, and detailed meeting minutes (using audio recordings). | |

| In-depth semi-structured expert interviews (with OMM Project) | April 2017, August 2017, March 2018 (n = 3) | OMM, chief technical advisor | 1 conducted by first author and Myanmar research colleague, 2 conducted by second author. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. |

| August 2017, October 2017, November 2017, February 2019 (n = 4) | OMM Project technical staff | 2 conducted by first author and Myanmar research colleague, 2 conducted by second author | |

| January 2018, March 2018 (n = 2) | OMM Project facilitator of the MSP | 1 conducted by first author and Myanmar research colleague, 1 conducted by second author | |

| September 2017 (n = 1) | Focal line department representative (the coordinator of the MSP) | Conducted by first author and Myanmar research colleague | |

| Short narrative interviews (with OMM Project) | Frequently between April 2017 and March 2019 (n = 12) | OMM Project chief technical advisor | Conducted by first author, usually without audio-recording |

| January 2018 (n = 1) | OMM Project technical staff | Conducted by first author, without audio-recording | |

| Retrospective self-evaluation (with the OMM Project) | August 2021 | Former and present OMM Project technical staff and chief technical advisor (n = 3) | Short written survey with multiple-choice and qualitative questions on the achievements of the MSP; conducted by first author |

| Communicated Goal | How It Was Communicated | Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| (A) Land use assessment (via mapping, developing a spatial data platform, etc.) | Regional minister (1); terms of reference (2); ideas of OMM Project (4) | Several achievements under the supervision of the MSP (e.g., mapping several oil palm concessions with a multi-stakeholder participation, one extended report on a concession in Yebyu township, etc.). However, different stakeholders had different perceptions of what “land use assessment” should entail. The main achievements for this goal were completed after the MSP had fallen apart. 1 |

| (B) Addressing and resolving land conflicts and supporting land use planning for remaining land | Regional Chief Minister (3); ideas of OMM Project (4) | Achieved for very few local cases during the existence of the MSP. No direct impact of the MSP visible at the regional level. 2 |

| (C) Assessment of the quality of investments in the oil palm sector | Ideas of OMM Project (4) | No achievements during the existence of the MSP. 3 |

| (D) Developing sectoral policies and approaches to a sustainable oil palm industry | Ideas of OMM Project (4) | No achievements. |

| List of Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| 1 | The representation of stakeholders in the multi-stakeholder platform (MSP) needs to be carefully assessed (who will be included, who excluded). A participatory actor analysis (including power and conflict analysis) before defining the stakeholders is a key preparation. |

| 2 | The mandate including vision, intermediate goals, scope, time horizon, and decision-making competences of the MSP must be clearly defined from the very beginning. At the same time, the MSP should also define procedures for adapting these definitions, whenever adaptations appear necessary due to changing circumstances. It can be useful if the mandate in a first place is related to a technical solution (such as in our case providing accurate spatial data on land) instead of a purely political and controversial topic (such as in our case the land use conflicts per se). This might motivate the participants to collaborate despite existing tensions. However, at some point, the focus on the technical solution will not be sufficient anymore and the MSP needs to address the overall source and policy of the problem (e.g., land governance mechanisms). |

| 3 | An effective leadership of the MSP must be in place. The leader(s) must be motivated, available, and powerful and/or legitimate enough to make the MSP thrive. Additionally, the formally and informally powerful stakeholders inside and outside the MSP need to support—or at least approve—the MSP and its mandate, otherwise the MSP will be blocked. The willingness and ability of all these leaders and powerful stakeholders to learn and reflect needs special attention. |

| 4 | The roles, responsibilities, and decision-making competences of the participating groups (or even of each stakeholder, if useful) must be defined very early in the process. Additionally, for this point, the MSP should agree on a procedure for adaptations. Moreover, there should be someone responsible for and capable of effectively coordinating and driving the MSP forward, such as a secretary or focus person/group with the respective authority and legitimacy. |

| 5 | Secured time, financial, and human resources form the basis for an effective MSP. |

| 6 | If the envisioned mandate and outputs are related to decision-making (e.g., political or legal decisions on how to redistribute land after a war), the effective access to decision-making processes must be guaranteed. |

| 7 | A respectful and constructive stakeholder management is of utmost importance. All participants need to develop their trust in each other as well as in the MSP itself. During the MSP meetings, a conflict-, power-, and equality-sensitive facilitation is crucial. |

| 8 | A proactive and transparent information and communication approach is key to the above-mentioned points. The frequency and channels of information and communication can jointly be agreed on in the MSP. |

| 9 | Tangible intermediate outputs and success foster the continuance and effectiveness of the MSP, as they keep the participants motivated and increase their ownership. |

| 10 | Depending on the context and case, the MSP is in need of various expertise (e.g., in the form of advising). Certain expertise and support might be needed in each MSP, which addresses land conflicts, for example: facilitation, communication management, conflict management, land governance (mechanisms), legal basis, and coordination/operational management of the MSP. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.M.; Oberlack, C.; Hunt, G.; Schneider, F. The (In)Ability of a Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts—Lessons Learnt from an Oil Palm Landscape in Myanmar. Land 2022, 11, 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081348

Lundsgaard-Hansen LM, Oberlack C, Hunt G, Schneider F. The (In)Ability of a Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts—Lessons Learnt from an Oil Palm Landscape in Myanmar. Land. 2022; 11(8):1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081348

Chicago/Turabian StyleLundsgaard-Hansen, Lara M., Christoph Oberlack, Glenn Hunt, and Flurina Schneider. 2022. "The (In)Ability of a Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts—Lessons Learnt from an Oil Palm Landscape in Myanmar" Land 11, no. 8: 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081348

APA StyleLundsgaard-Hansen, L. M., Oberlack, C., Hunt, G., & Schneider, F. (2022). The (In)Ability of a Multi-Stakeholder Platform to Address Land Conflicts—Lessons Learnt from an Oil Palm Landscape in Myanmar. Land, 11(8), 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081348