Abstract

With the intensification of the contradiction between living space and population growth, it is necessary to improve the effectiveness of urban residential land allocation. This study systematically reviews 169 papers following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol to collect and collate the contributing factors that affecting the supply of and demand for urban residential land for different countries, and a statistical analysis of long-term series data is conducted to further verify the rationality of the contributing factors. Based on systematic literature review and empirical analysis, the contributing factor set is constructed to serve the decision-making of residential land allocation. The main findings indicate that the population, house price, income, rent, mortgage loan, investment, the number of affordable houses, GDP, employment, housing stock and migration are the general contributing factors that significantly affect allocation of urban residential land. A systematic understanding of general contributing factors will help decision-makers more intuitively realize the urgent problems of urban residential land supply. Moreover, there are some specific contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land in different types of countries, and the identification of specific contributing factors provides different perspectives on residential land allocation for the differentiated global development status. The contribution of this study is to assist decision-makers formulate more rational residential land allocation strategies by systematically sorting out the contributing factors influencing residential land allocation.

1. Introduction

Land is an essential natural resource that supports the survival and prosperity of humanity [1,2]. However, the pervasive trade-offs in resource-constrained land systems are a warning that we cannot develop land uncontrollably [3]. As countries around the world are experiencing faster development than ever, the scarcity of land has led to an imbalance between the supply of and demand for urban residential land [4,5]. The government is the central agency for formulating land-use allocation strategies [6]. In order to solve the socio-economic problems caused by the shortage of housing, many countries have proposed response measures to optimize the allocation of residential land [7,8]. The Australian Bureau of Statistics received funding in 2018 to investigate indicators to measure the relationship between land use and housing supply [9]. The UK government has issued new land-use planning guidance in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), called the 5-year housing land supply (5YHLS) [10], to provide an indication of whether there is sufficient available land to meet the demand for housing construction set out in adopted strategic plans for the next five years [11]. Based on the opinions surveyed in public participation activities [12], Hong Kong SAR established the Task Force on Land Supply in September 2017 to formulate a general decision framework of recommendations on the overall land supply planning and a prioritization of different land supply options [13]. The government of China has established the Ministry of Natural Resources to monitor land market dynamics and provide land-use data [14]. Since 2010, the Ministry of Natural Resources has published quarterly land price monitoring reports in major cities to analyze the real-estate market situation [15].

The allocation of urban residential land is a behavior of public management, which requires governments to fully understand the contributing factors that affect the supply of and demand for residential land [16,17,18]. Previous research has widely discussed the contributing factors that affect the housing demand and supply [19,20,21], and the determination of contributing factors usually adopts a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses [22,23]. A residential area is land used in which housing predominates and is an indispensable part of urban space. Housing is the main ground attachment of residential land, and its supply and demand directly affects the supply of and demand for residential land [24,25]. The impact of a single contributing factor on housing demand has been extensively empirically studied [26]. According to macroeconomic theory, house price is the primary factor influencing housing demand and supply [27,28,29]. By the law of housing markets, housing demand increases when the house price decreases, and housing supply increases when the house price increases [30]. In addition, the role of the population in housing demand is widely debated [31]. Conventional wisdom suggests that population is an important contributing factor in stimulating housing demand [32,33]. However, with the intensification of labor circulation, employment demand increases, and changes in housing preferences, the mechanism of population changes on housing demand is more complicated [34,35]. Some studies have documented that the disposable income of residents is an important indicator reflecting the affordability of housing purchases, and housing needs and preferences of different income groups are different [36]. Moreover, policy-making has been recognized as a key instrument for governments to macro-control housing demand and supply [37].

Government intervention in the land market is an important factor influencing the amount of land available for housing development, which in turn affects the supply capacity of housing [38,39]. The main form of government intervention is to formulate land-use regulations [40,41,42,43], which can affect residential land allocation in various ways because not only does it limit the size, use and location of parcels, but it also affects costs indirectly through sometimes long-lasting permitting procedures which raise the final cost of housing construction [44]. Moreover, due to the diversity of institutional environment and development status in different countries, the land-use regulations have different impacts on the housing supply [45,46]. For example, the negative relationship between land-use regulation and the growth of houses has been confirmed in present-day Canada [47]. On the contrary, land-use regulation played a positive role in Russia from 2015–2016. In this period, Russia was facing an economic crisis, and the housing sector enjoyed an unprecedented level of state support to prevent a housing crisis.

With different political, economic, cultural and consumer behaviors, there are differences in national preferences for housing [48,49]. The complete legal protection for tenants and the high threshold of mortgage loans have made Germans more inclined to rent [50]. Home ownership rate in Germany is lower overall than in most other developed countries [51,52,53], averaging 52.48% from 2005 to 2018. Therefore, rent is an influencing factor that must be considered in the allocation of residential land in Germany. In contrast, the Chinese people prefer to buy houses due to the influence of traditional thinking [54], housing policies, children’s education [55] and chaos in the rental market [56]. Moreover, in some countries or cities, such as Australia, Canada and London, foreign investment plays an important role in the housing supply [57,58]. Exceptionally, the impact of foreign investment on housing supply is not significant in Paris and Amsterdam [59,60].

Achieving a balance between land supply and demand is a necessary path for sustainable urban development. In the process of urban land development, the government has tried to comprehensively consider the contributing factors influencing the allocation of residential land from multiple objectives [61,62]. However, the lack of systematic sorting of contributing factors often leads to limitations in decision-making. Therefore, a full understanding of the differential contribution of to the various residential land allocation factors can help decision-makers make rational urban land development plans [63]. Previous studies have noted that residential land supply did not keep pace with increased demand in many large cities after the government strengthened the intervention in land markets. In addition, some studies have shown that the identification of contributing factors has become an important step in constructing the supply and demand model of urban residential land [64,65,66]. However, most existing studies focus on housing demand and supply rather than on residential land, and some studies have verified the influence of only a single factor on housing demand and supply [67] or the indicator systems that affect the housing demand and supply in only one country or city [68]. Few studies have studied the contributing factors influencing allocation of urban residential land from a global perspective. To fill these knowledge gaps, this study aims to (1) follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol to select out reference publications for research on residential land allocation worldwide, and (2) establish a general and specific contributing factor set influencing the allocation of urban residential land to assist decision-makers perform more efficient land use planning. The present study is the first attempt to systematically review and analyze the contributing factors of urban residential land allocation and to draw general lessons from published research.

This study innovatively constructs a research framework combining systematic literature review and empirical analysis, and collects and sorts out the contributing factors influencing urban residential land allocation from a global scale, which provides a basic reference factor set for decision-makers to formulate land development strategies. The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the research framework, data and methodology. Section 3 presents the empirical results of systematic literature review and statistical analysis. Section 4 discusses the policy implications of this study. Section 5 draws conclusions from this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Considerations for Study Framework

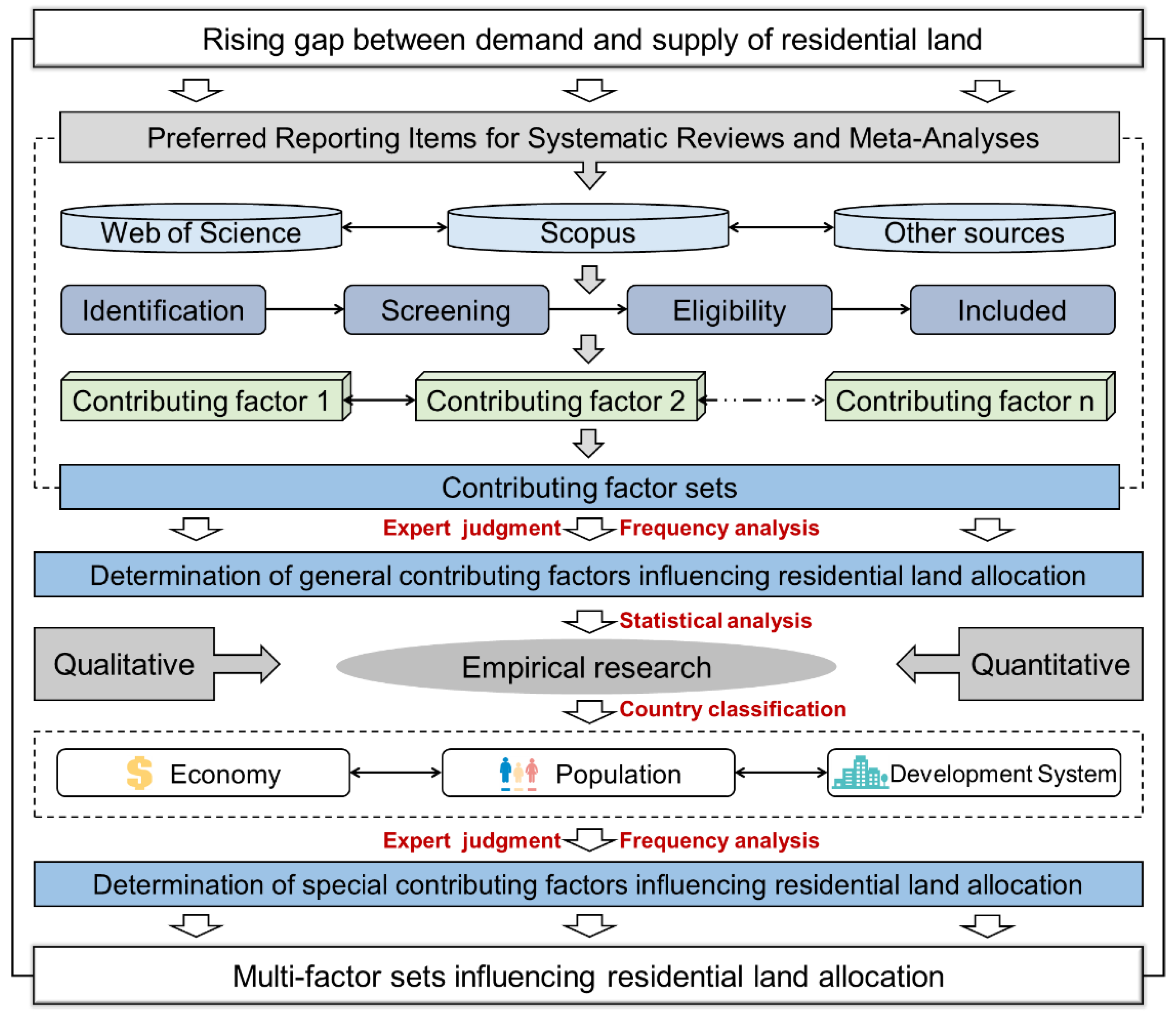

Globally, the continued growth of the population has led to an imbalance in the supply of and demand for urban residential land. To realize the efficient use of land resources, the policymakers inevitably consider contributing factors that affect the allocation of urban residential land. This study designed a systematic review and empirical framework to summarize the contributing factors that affect the allocation of urban residential land (Figure 1). First of all, this study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol [69] to search the relevant literature from the multi-source database (Web of Science Core Collection database, Scopus database and other sources). Secondly, the contributing factor sets influencing allocation of urban residential land were obtained through literature reading and crucial information extraction. Next, through frequency analysis and expert experience judgment, the general contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land were determined, and the method of mathematical statistics was applied to verify the applicability of the general contributing factors. Importantly, the specific contributing factors with country characteristics also play an important role in the allocation of urban residential land. To further improve the pertinence of the contributing factor sets, the reviewed countries were divided into three types according to economic development level, population density and land ownership structure, and the specific factors influencing residential land allocation in those different types of countries were determined.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

2.2. Data Extraction and Procedures

2.2.1. Selecting Research Literature Using Formal Strings

Potentially relevant studies were identified through a database search in Web of Science and Scopus. Our research applied the search terms on “Title” only. The corresponding publications selected in this study were limited to papers written in English (or papers in other languages but with English versions) from published journals, conferences and books. The potentially relevant publications selected using the stated string words from each database are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strings, sources, and the corresponding publication numbers (search date: 11 October 2022).

2.2.2. Systematic Screening of the Corresponding Studies

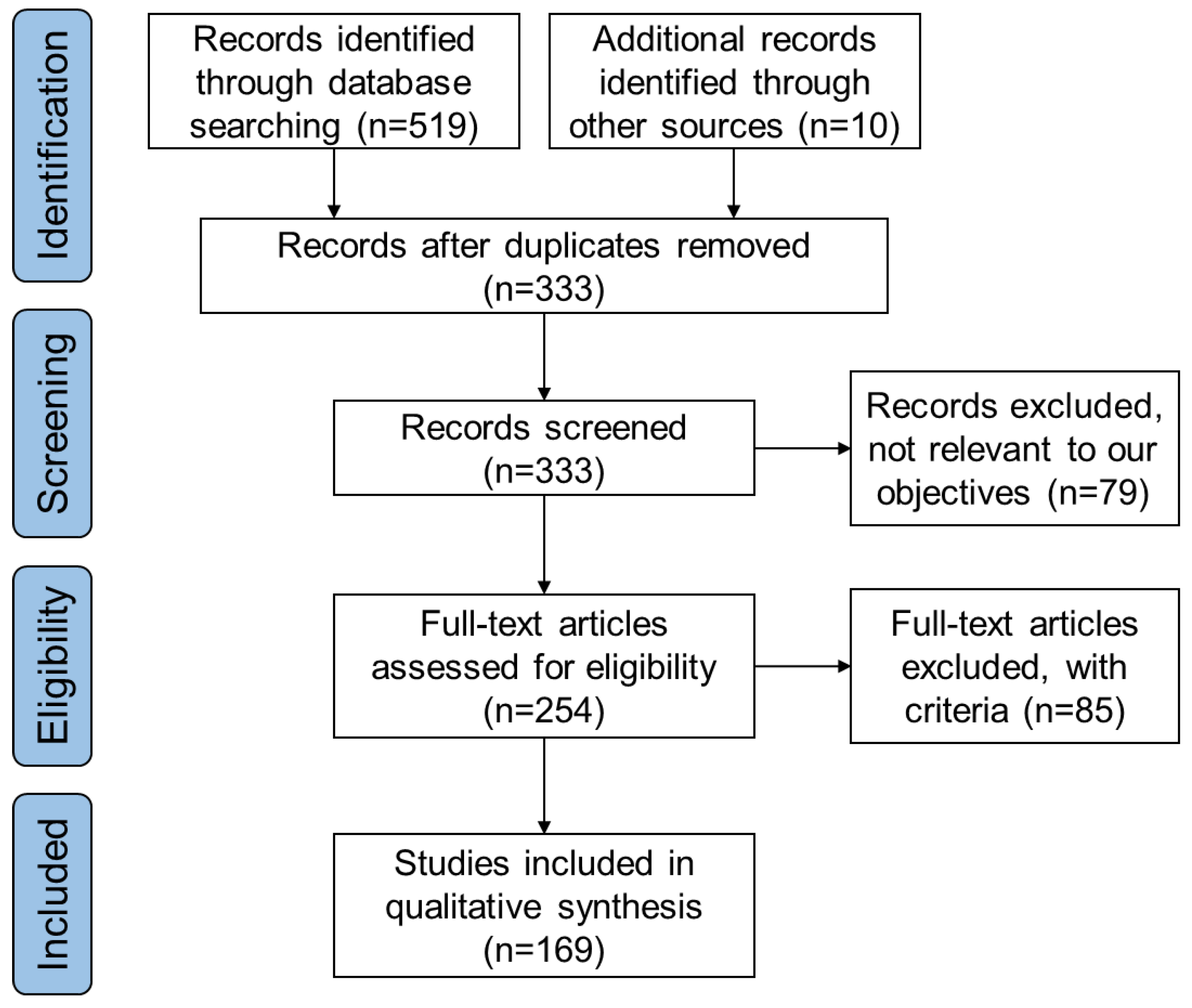

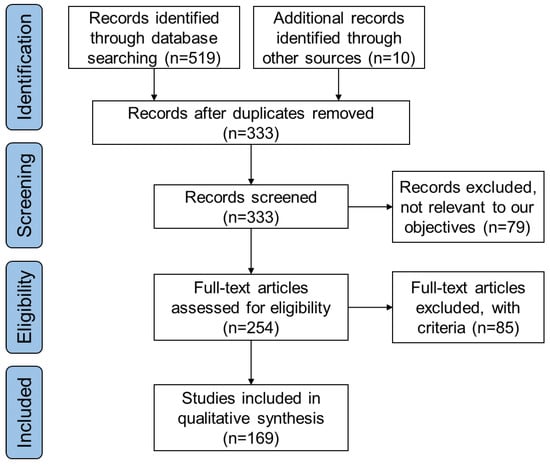

The PRISMA protocol consists of a four-stage systematic screening procedure for the inclusion and exclusion of publications for review. First of all, based on the identify strategy, a total of 529 papers were initially selected from Web of Science, Scopus, and other sources. Secondly, all relevant publications were sorted in Excel and duplicate records were removed. A total of 333 articles were left for the next stage of screening. Next, we excluded the publications which were not directly relevant to our study objectives. In this stage, 79 publications were excluded, and 254 studies were retained for full-text assessment. Based on the objectives of our study, the publication screening followed the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (a) focuses on residential land allocation; (b) explicitly proposes the contributing factors influencing the allocation of residential land; (c) excludes all studies related to rural residential land allocation; (d) excludes studies without a clear study area. Finally, we comprehensively read these 254 studies, and finally included 169 studies for our systematic review (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search.

2.3. Country-Wise Distribution of Reviewed Studies

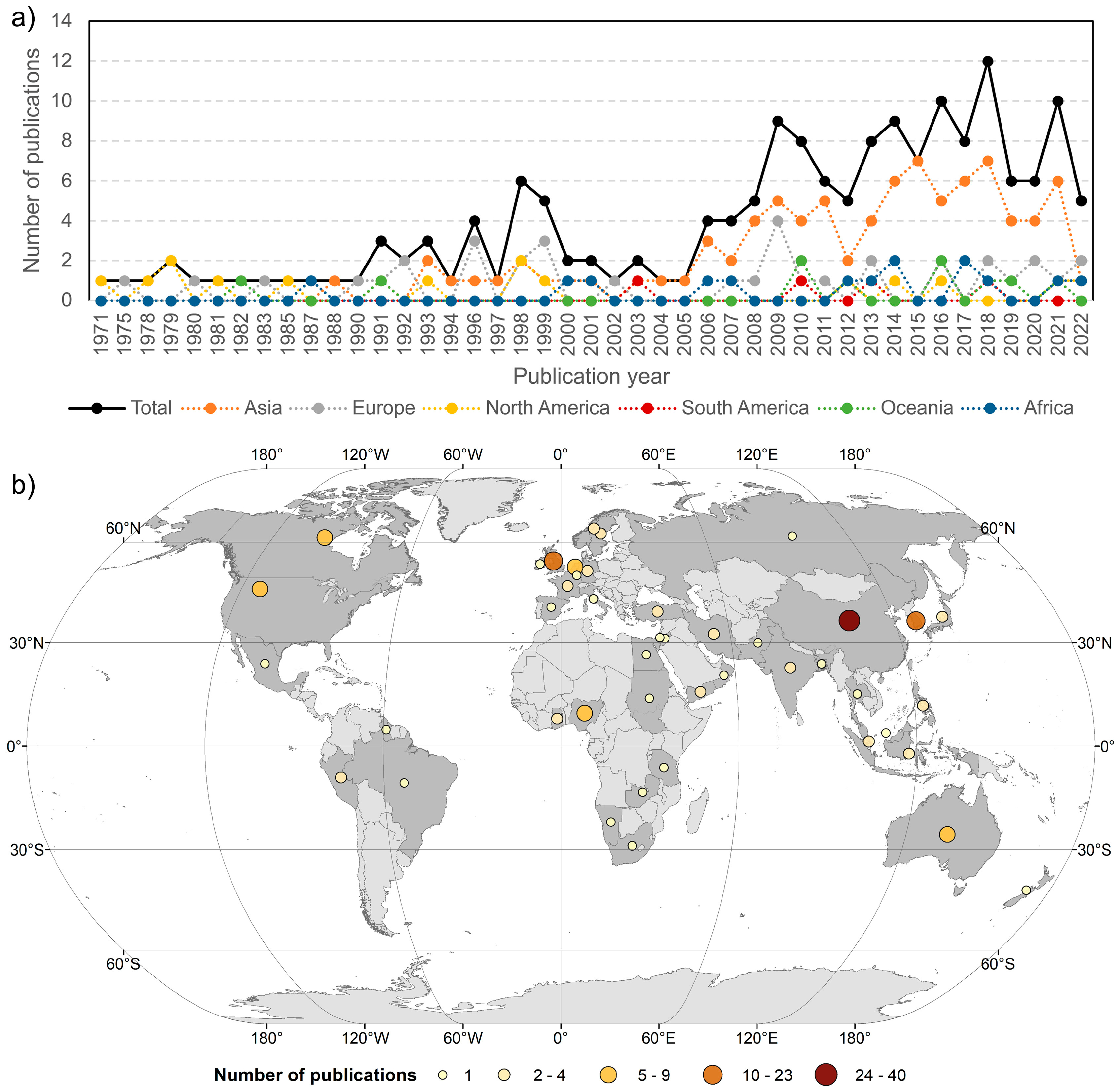

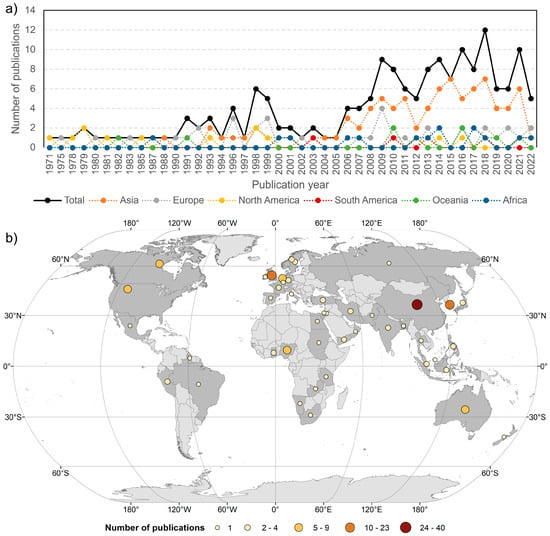

The initial search contained 529 relevant studies, but only 169 studies met the research objectives of this study. These publications started to appear from 1971 and the number of published studies has shown a trend of increasing volatility (Figure 3a). In addition, the global-scale distribution of these publications provides a clear perspective of how residential land allocation was emphasized in different countries. The results of PRISMA show that urban residential land allocation studies were conducted in 22.8% (n = 44) countries globally (193 member states of the United Nations), including 3 countries in South America, 2 countries in Oceania, 3 countries in North America, 6 countries in Africa, 18 countries/provinces/cities in Asia, and 10 countries in Europe.

Figure 3.

(a) Number of publications referring to residential land allocation, distinguished by continent; (b) spatial distribution and number of case studies used in the publications.

The case studies presented in the publications were unevenly distributed across the world (Figure 3b). More than half of all case studies were located in Asia (53.25%), more than one fifth of all case studies were located in Europe (21.3%), while only a few case studies were located in South America (2.37%). In total, most case studies were carried out in China (n = 40), Korea (n = 23), the United Kingdom (n = 17), the United States (n = 9) and Australia (n = 9).

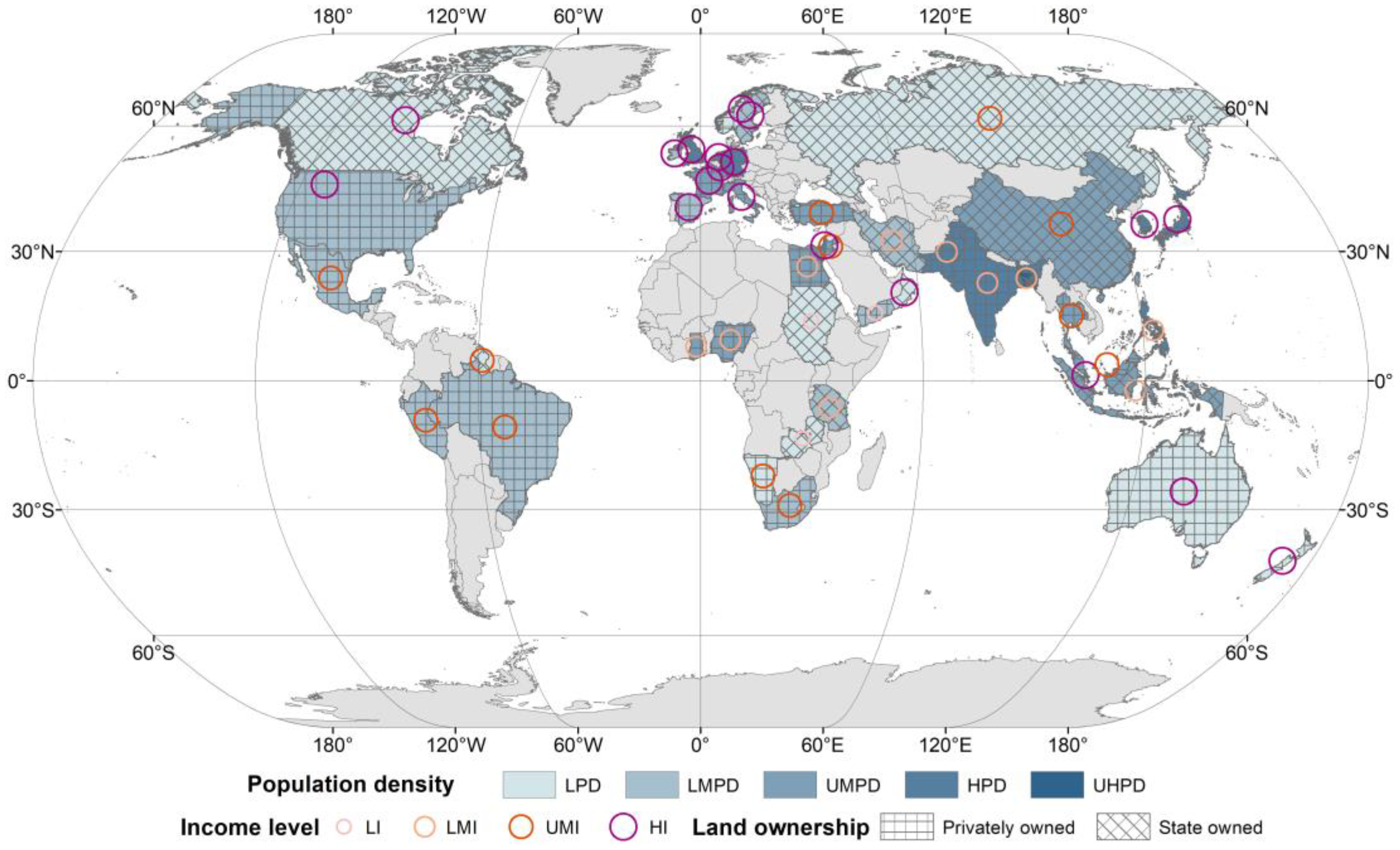

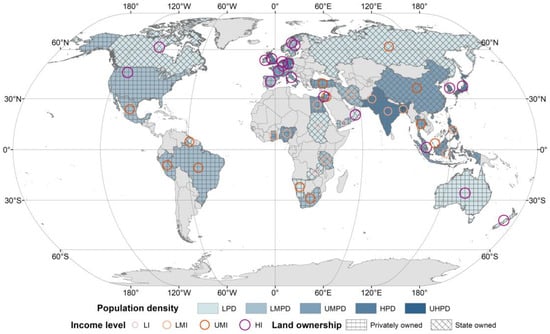

2.4. Classification of Case Countries

To investigate specific contributing factors, this study classifies the reviewed countries from the perspectives of economy, population and development system (Figure 4). It is worth noting that we divide the case studies of China into Chinese mainland, Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan Province. This is mainly because Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan province are operating on the basic national policy of “one country, two systems”, and the differentiated development system has led to differences in land supply decisions between China mainland, Hong Kong SAR, and Taiwan province. Importantly, the supply of residential land in Hong Kong SAR has received extensive attention from academia and the local government, and the land supply strategy in Hong Kong SAR can provide a comparative sample for similar high-density city-states, such as Singapore.

Figure 4.

Classification of types of case countries.

2.4.1. Classifying Case Countries by Income Level

The intensity of land development is significantly affected by the level of economic development. Countries with different economic levels have different development goals when allocating residential land. To achieve a global consensus on the division of economic levels, the classifications of global income levels follow the standards formulated by the World Bank which are classified by gross national income (GNI) per capita, with income levels characterized as high income (HI), upper medium income (UMI), lower medium income (LMI), and low income (LI) levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Income level classification 1.

2.4.2. Classifying Case Countries by Population Density

Population density directly reflects the population-supporting capacity of the land. The difference in population density also leads to the diversification of residential land allocation decisions in different countries. [70,71]. Countries with higher population density tend to use land resources more intensively. According to the 2021 population density data released by the World Bank Database, this study employs the quartile method to divide the case countries/province/cities into five categories, namely ultra-high population density (UHPD) countries, high population density (HPD) countries, upper-middle population density (UMPD) countries, lower-middle population density (LMPD) countries and low population density (LPD) countries. UHPD countries/cities only include Bangladesh (1277.6 per km2), Hong Kong SAR (7060.1 per km2) and Singapore (7691.9 per km2), which is much higher than other case countries. HDP countries are mainly concentrated in Asia and Europe, and LDP and LMDP countries are mainly concentrated in the Americas.

2.4.3. Classifying Research Objects by the Structure of Land Ownership

Land in mature market-economy countries are not completely owned by the private sector or by the state [72]. State-owned land plays an important role in regulating the land market, increasing national fiscal revenue and maintaining public social welfare [73].Due to the differences in national conditions, the structure of land ownership varies between countries. This study divides the case countries into two types: countries dominated by state-owned land (where state-owned land accounted for more than 50%) and countries dominated by privately owned land (where privately owned land accounted for more than 50%). It is worth noting that some countries do not have clear statistics on the proportion of state-owned and privately owned land. Therefore, this study determines the structure of land ownership through national land codes, reports and academic papers. Countries dominated by state-owned land are mainly distributed in Asia, while countries dominated by privately owned land are mainly distributed in Europe and America.

2.5. Limitations

Considering the completeness of the data (each contributing factor must have time-series data to ensure the accuracy of statistical analysis), we only selected China and Norway for applicability verification. In addition, although we have selected Web of Science and Scopus databases for information retrieval, we cannot guarantee that all corresponding publications were correctly identified. This is predominantly because of the subjective judgment used in the process of publication screening. For instance, only reading the title, key words and abstract does not always ensure that useful information can be obtained. Therefore, there may be statistical errors in the frequency analysis of our research; however, this error will not affect the determination of the main contributing factors.

Our research is an attempt to deeply investigate the differences in contributing factors considered by countries in the allocation of urban residential land, and the research results show that this attempt is meaningful. Therefore, the contributing factor set proposed in this study will assist decision-makers to preliminarily determine which factors need to be considered in the process of residential land allocation. In the actual land allocation process, decision-makers need to further determine the main contributing factors according to the actual situation. In addition, there are very few countries whose land is completely owned by the state/private sector. According to the investigation, only China, Vietnam, North Korea and Cuba do not recognize the existence of privately owned land. Because the land property rights system of most countries is a mixture of public and private, this study cannot decisively determine the country’s ownership of land. This study attempts to classify countries based on the proportion of state-owned land and privately owned land, and investigates whether there are differences in the contributing factors in countries with different land ownership structures.

3. Results

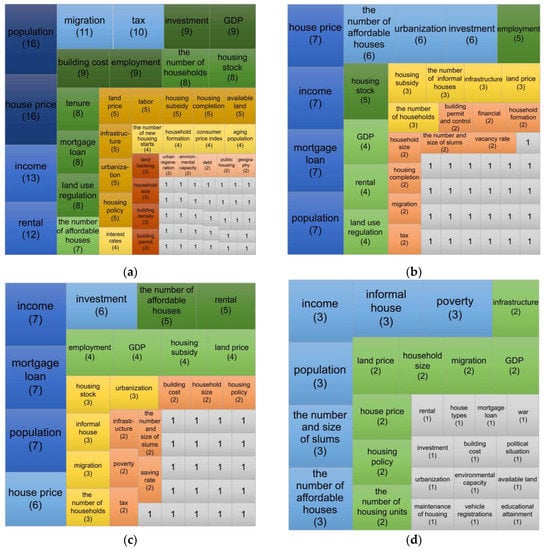

3.1. Frequency Analysis of Contributing Factors for All Case Countries

This study applies the synonym-merging method to integrate the collated contributing factors, and summarizes 94 contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land. Through frequency analysis, the main contributing factors considered by research countries are population, house price, income, rent, mortgage loan, investment, the number of affordable houses, GDP, employment, housing stock and migration, with frequencies of 32, 30, 29, 22, 22, 22, 20, 18, 18, 16 and 16 respectively. In addition, the number of households, urbanization, tax, land price, land-use regulation, building cost, infrastructure and housing subsidy are secondary important factors that affect the urban residential land allocation (Figure 5). Contributing factors with a frequency less than 3, such as tourism, apartheid, crime rate, et al., are supplementary factors to be considered in the decision of urban residential land allocation under specific scenarios, which vary according to the complexity of local conditions.

Figure 5.

Frequency analysis of contributing factors for all case countries.

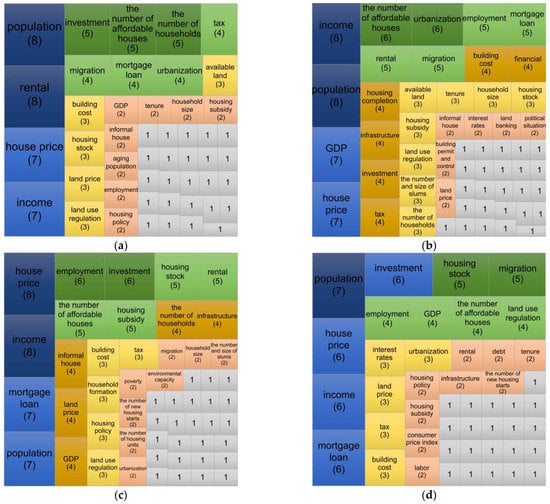

3.2. Frequency Analysis of Contributing Factors in Countries with Different Income Levels

There are differences in contributing factors considered by countries with different levels of economic development when allocating urban residential land (Figure 6). Population and income are general contributing factors that affect allocation of urban residential land. Poverty, infrastructure, the number of informal houses and the number and size of slums are specific contributing factors considered by most LMI and LI countries. Mortgage loan, investment and the number of affordable houses are general contributing factors considered by LMI and UMI countries. It is worth noting that UMI countries generally regard the urbanization level as an important factor affecting the allocation of urban residential land, which is mainly because such countries are currently in the rapid development stage of urbanization, and the rapid expansion of cities will inevitably bring greater demand for residential land. Rent and migration are specific contributing factors affecting urban residential land allocation in HI countries.

Figure 6.

Frequency analysis of contributing factors in different income-level countries. (a) HI countries; (b) UMI countries; (c) LMI countries; (d) LI countries.

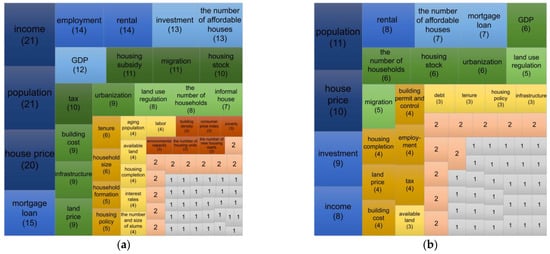

3.3. Frequency Analysis of Contributing Factors in Countries with Different Population Density

Population, income and house price are contributing factors generally considered by all case countries. In Singapore, Bangladesh and Hong Kong SAR, how to use limited land resources to support a growing population is an important challenge for these three countries/cities. The number of affordable houses is an essential factor that Singapore and Hong Kong SAR pay attention to when allocating urban residential land. Many countries with high population density, such as Korea, Japan, the Netherlands, the Philippines and Israel, usually regard rent, the number of households and the number of affordable houses as the important contributing factors influencing the allocation of residential land. Urbanization is a specific influencing factor considered by most UMPD countries. For LMPD and LPD countries, mortgage loan, investment, employment and housing stock are important factors affecting residential land allocation (Figure 7). In many LPD countries, migration plays an important role in residential land allocation.

Figure 7.

Frequency analysis of contributing factors in countries with different population densities. (a) HDP countries; (b) UMDP countries; (c) LMDP countries; (d) LDP countries.

3.4. Frequency Analysis of Contributing Factors in Countries with Different Land Ownership Structure

Regardless of the structure of land ownership, income, population, housing price, investment, mortgage loan, rent, the number of affordable houses, GDP, housing stock and urbanization are the contributing factors that are commonly considered in the allocation of urban residential land (Figure 8). However, differences in land ownership structures lead to the diversification of factors affecting the allocation of urban residential land in different countries. Countries dominated by privately owned land have limited control over land use, and the demand and supply of residential land is mainly determined by the real estate market. Therefore, the main contributing factors affecting the real estate market, such as employment, housing subsidies, and taxes, are also contributing factors that need to be considered in the allocation of residential land. In contrast, countries dominated by state-owned land have the initiative in land allocation, and they tend to improve land-use efficiency and ensure people’s well-being through rational allocation of residential land. The results indicate that the relative frequencies of the number of households, land-use regulation and migration are all greater than 35%, which are contributing factors recommended to be considered in the allocation of urban residential land in countries dominated by state-owned land. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that in China, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, Turkey and the Netherlands, building permits and control are also essential factors affecting the allocation of urban residential land, which is mainly because the government departments uniformly control the land development in these countries. Overall, there is no significant difference in the contributing factors influencing urban residential land allocation in these two types of countries, which reflects the limitations of this study in dividing case countries into two categories according to land ownership structure. Nevertheless, this study provides a meaningful attempt at subsequent in-depth research on urban residential land allocation.

Figure 8.

Frequency analysis of contributing factors in countries with different land ownership structure. (a) Countries dominated by privately owned land; (b) Countries dominated by state-owned land.

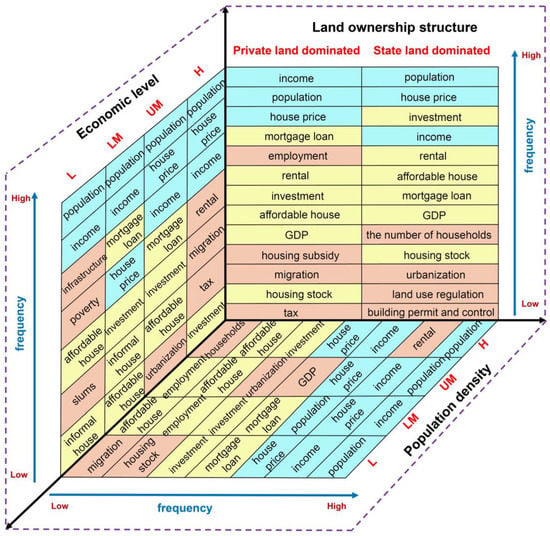

3.5. Integration and Comparison of the Contributing Factors

Based on the research results in Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, this study integrated the main contributing factors affecting the allocation of residential land in different types of countries, and we can draw a three-dimensional quadrant frequency graph of the contributing factors to conduct comparative analysis (Figure 9). Population, income and house price are key contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land in all case countries. Mortgage loan, investment and the number of affordable houses are the contributing factors that need to be paid attention to in countries with medium economic levels and low- and medium- population density. In addition, some special factors also have a significant impact on residential land allocation. For example, urbanization is an influencing factor that needs to be paid attention to in state-owned-land-dominated countries with upper-middle population density, migration is a contributing factor of importance in privately owned-land-dominated countries with high economic level and low population density, rent is an important factor that affects residential allocation in countries with high economic level and high population density, and employment is an important factor that affects residential land allocation in privately owned-land-dominated countries with lower-middle population density.

Figure 9.

The three-dimensional quadrant frequency distribution of the contributing factors.

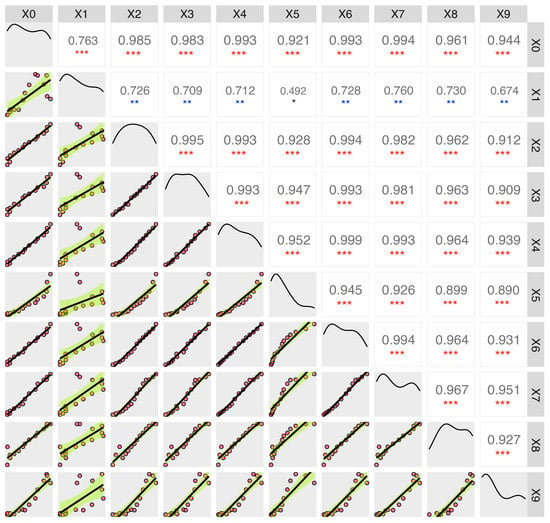

3.6. Empirical Research to Verify the Applicability of Contributing Factors

Comprehensively considering the availability of time-series data, the two countries of China (state-owned land dominates, upper-middle income, upper-middle population density) and Norway (privately owned land dominates, high income, low population density) were selected as objects for case study, with the purpose of verifying the applicability of the general contributing factors obtained in this study. Quantitative data for the case countries are mainly from the national official statistical website. Before statistical analysis, the time-series data of all contributing factors were normalized using Min–max normalization. In this study, residential land allocation refers to the balance between the supply of and demand for residential land through land resource management. Therefore, we selected the long-term series of residential land area to quantify the allocation of residential land, which reflects the dynamic characteristics of residential land over time.

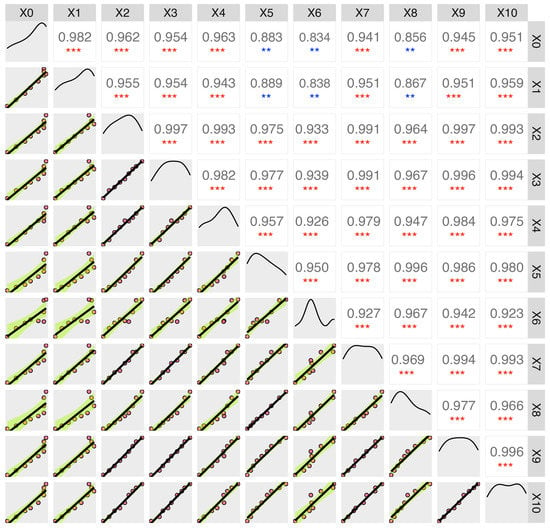

The results of correlation analysis show that all general contributing factors play a positive role in promoting the demand for residential land. In China, except for affordable housing, the correlation coefficients between other contributing factors are all greater than 0.9. The significance level p values of all contributing factors are less than 0.01 (Figure 10). However, the number of affordable houses is still an important factor that the Chinese government needs to consider in addressing the housing shortage. On 8 October 2007, the Ministry of Land and Resources issued a notice on further strengthening macro-control of the land supply, requesting priority to supply affordable housing to low- and medium-income households. The increase in the construction of affordable housing has stimulated an increase in the supply of urban residential land.

Figure 10.

Correlation coefficient matrix of contributing factors influencing allocation of urban residential land in China (X0, X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9 represent residential land area, affordable houses, population, house price, income, housing loan, GDP, investment, employment, and housing stock, respectively). Arabic numerals represent the Pearson correlation coefficient between the different contributing factors. ***, **, and * are significance levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively. The curves in the figure are kernel density estimates for different contributing factors.

In Norway, the correlation coefficients between the number of affordable houses, population, house price, income, investment, housing stock, housing rent and residential land area are greater than 0.9, and the significance level p values of these contributing factors are less than 0.01. The correlation coefficients between GDP, employment, housing loan and residential land area are greater than 0.8, and the significance level p values of these contributing factors are less than 0.01 (Figure 11). It is worth noting that the number of affordable houses has the most significant impact on the promotion of residential land supply. Norwegian housing policy differs greatly from several other countries in Europe, which is based on the premise that people should own their own property. According to Eurostat, in 2019, about 80% of all Norwegians owned their own properties. In neighboring Denmark, only 59% of people own their own property, and in Sweden the home ownership rate is 64.5%. In Germany, the home ownership rate is about 50%. The higher home ownership rate increases the demand for affordable housing, which directly affects the allocation of residential land in Norway [74].

Figure 11.

Correlation coefficient matrix of contributing factors influencing allocation of urban residential land in Norway (X0, X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10 represent residential land area, affordable houses, population, house price, income, housing loan, GDP, investment, employment, housing stock, and housing rent, respectively). Arabic numerals represent the Pearson correlation coefficient between the different contributing factors. *** and ** are significance levels of 1% and 5%, respectively. The curves in the figure are kernel density estimates for different contributing factors.

4. Discussion

In the context of urban housing shortage, how to maximize the efficiency of urban residential land use has become a global urgent challenge. Land resources in many countries are currently facing illegal phenomena such as idleness, hoarding, and unauthorized changes in use [75,76]. In addition, due to the problems of cumbersome and long-term administrative approval procedures, asymmetric market information, and ambiguous supply, it is often difficult for the supply of residential land in some countries truly reflect the actual market demand, which weakens the leverage of land on national economic development [77]. To solve this problem, decision-makers need to consider which factors influence the allocation of residential land.

Globally, providing shelter for human beings is the common function of residential land. The change in the supply of and demand for urban residential land is the result of the common influence of many factors. The general contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land have been widely recognized. Moreover, differences in economic, demographic and land tenure lead to the diversification of contributing factors considered by governments when allocating urban residential land. At present, no studies have systematically reviewed the contributing factors affecting urban residential land allocation on a global scale. The purpose of this study was to innovatively establish a general–specific contributing factor set to assist different countries to formulate more reasonable residential land allocation strategies. Based on the research results, it is recommended that the governments first consider the general contributing factors determined in this study when formulating residential land allocation strategies. More specifically, housing price is a primary factor affecting residential land allocation. With the growth of house prices, the increase in consumer psychological expectations has led to a substantial increase in the demand for residential investment [78], and the confidence of real estate developers in the market will also increase, which comprehensively leads to an increase in the demand for residential land [79,80]. Real estate investment is another important contributing factor influencing the supply of residential land. Developers decide how much to invest in residential development based on real estate market conditions, which further affects the efficiency of residential land development and utilization [81]. The sluggish real estate investment environment will lead to a large amount of vacant residential land, thereby exacerbating the imbalance between the supply of and demand for residential land.

Countries at different levels of development have different understandings regarding the allocation of urban residential land. Immigration is an important contributing factor influencing allocation of urban residential land in HI countries. Affected by the European refugee crisis and the globalization, a surge of asylum-seeking families and immigrants has been flooding into Singapore, German, France, Spain, Switzerland, Japan, Australia and other HI countries over the last two decades [82]. The increase in the number of immigrants will increase the demand for housing, which will affect the supply of urban residential land [83,84,85]. For instance, immigration accounts for 80% of Switzerland’s annual population growth, and therefore profoundly impacts the residential land needs. To accurately predict future housing demand, a novel simulation framework was proposed to assess the impact of immigration on urban spatial planning [86]. Therefore, policymakers in developed countries should pay attention to the positive effect of immigration on the growth of demand for urban residential land. Moreover, some developed countries are showed an expanding interest in the sustainability of land allocation, such as climate responsive approaches to residential construction, energy efficiency of unit residential land [68], and the coordination of land supply and wildlife habitats [87]. Cities with high level of modernization and development should improve the overall aesthetic design of the urban space while meeting the rigid housing needs of residents. Mitigating climate change, improving air quality and maintaining habitat quality through the optimal layout of urban spaces will become an important goal that decision-makers need to consider when formulating urban planning. In other words, green, healthy and sustainable urban land development is the ultimate goal of residential land allocation.

The allocation of urban residential land in the least developed countries needs to focus on how to ensure people’s basic quality of life. A quarter of the world’s population live in slums and informal housing, and most slums and informal housing are concentrated in LI and LMI countries [88,89]. To alleviate the disruption of urban spaces caused by the expansion of informal housing and slums, governments should vigorously promote the supply of affordable housing for low- and middle-income families. The view that land development is an important means of ensuring people’s livelihood should be widely recognized in less developed countries. For countries with sufficient public land reserves, the supply of affordable housing can be guaranteed by entering into land development agreements with developers. In addition, the upgrading of informal housing and slums is another way to alleviate the pressure on residential land demand. Most emerging economies need to pay attention to the impact of urbanization on the allocation of urban residential land. According to existing research, the worst of the housing shortage by far is not in the wealthy cities of the developed country, but in the rapidly urbanizing cities of the developing country [90,91]. The rapid development of urbanization has accelerated the accumulation of rural populations into urban populations, resulting in most people with no fixed abode and the housing security system of cities is not sound [92]. The acceleration of urbanization inevitably leads to the expansion of urban space, and the agricultural land, ecological land and unused land around the city are occupied as developable construction land. Although emerging cities face less pressure from land scarcity, the dramatic changes in land use within cities present new challenges for policymakers. While vigorously developing residential land, emerging countries/cities should comprehensively consider the quality of residential construction and the rationality of land-use structure to ensure the balance of urban living space, production space and ecological space. Therefore, it is meaningful to learn from the advanced land-use planning experience of highly urbanized cities. The government can alleviate the housing shortage caused by rapid urbanization by developing more efficient and high-quality land development activities.

The population density directly determines the size of the human living space. As the population continues to grow, urban residential land in UHPD and HPD countries will become increasingly scarce. In response to rising housing prices driven by housing demand, the supply of public housing and affordable housing has become an important factor to alleviate the shortage of urban residential land. Public housing in Hong Kong SAR accounts for nearly 50% of total housing, and the figure in Singapore accounts for more than 80% [93]. However, the continued supply of public housing and affordable housing requires sufficient back-up land resources. For countries or cities with ultra-high population density, the scarcity of land is still a huge problem for public housing supply. Land-sharing schemes and the development of available brownfields are effective means of securing the supply of residential land. In addition, some coastal countries and cities ensure the supply of residential land through land reclamation [94]. The number of households is an important indicator affecting the potential demand for housing. Therefore, an accurate estimate of the number of households will help governments clarify the size, timing, and distribution of residential land supply. Our research shows that most countries with high population density are more concerned with the impact of the number of households on the allocation of urban residential land. According to the forecast of PBL Netherlands environmental assessment agency and statistics Netherlands (CBS), the number of households in the Netherlands will reach 8.4 million by 2030, with an increase of 640,000, which means that the Netherlands should develop more land for residential construction. Housing stock is an important factor reflecting the gap between the supply of and demand for residential land. The shortage of housing stock has prompted the government to supply more residential land to meet housing construction demand [95]. Conversely, the surplus housing stock warns the government to absorb the housing stock by reducing the supply of residential land. The digestion cycle of housing stock affects the size, structure and timing of residential land supply. Our research shows that LMPD and LPD countries with active housing construction activities generally have large housing stocks. For instance, according to statistics of the Spanish government, Spain’s residential dwellings increased by 24% between 2001 and 2011, while the population grew by only 5.85% over the same period, which indirectly reflects the extensive use of residential land in some Spanish cities. In response to the oversupply of housing, destocking and adjusting the housing supply structure are important tasks in residential land allocation.

In addition, our study recommends that countries with different land ownership structures should consider general contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land, while identifying different contributing factors according to the local characteristics of land tenure. In market economy countries dominated by privately owned land, mortgage, employment, housing subsidies, and taxes have become important factors affecting the allocation of urban residential land. The privately dominated land system has resulted in the development of residential land often being profit-oriented, which weakens the public service nature of the land. The increase in mortgage rates has led to a decrease in the willingness to buy a house, thus influencing the supply of and demand for residential land. Changes in the employment situation affect people’s ability to pay for housing. The decline in employment has led to a depression in the real estate market, which in turn has affected the allocation of residential land. Government intervention plays an important role in the allocation of urban residential land in countries dominated by state-owned land. For example, the Singapore government has established the Housing and Development Board (HDB) to vigorously develop public housing, which is an important way to positively intervene in the housing security system of residents [96]. Singapore’s HDB housing policy provides a meaningful reference for urban residential land development in similar countries or cities. In addition, the Chinese government’s land macro-control policies also have a significant impact on the allocation of urban residential land [45,97]. According to official statistics, from 2004 to the first half of 2011, China’s residential land accounted for about 30% of the total supply of urban construction land. However, since the second half of 2011, the growth rate of residential land area has begun to slow down, while the proportion of infrastructure land used for transportation and water conservancy has increased from more than 20% to more than 44% during the same period. It can be seen that the adjustment of national macro policies will significantly affect the structure of land supply [98]. Additionally, government intervention is also an important means of land allocation in countries dominated by privately owned land. In order to cope with the housing difficulties caused by the rapid growth of housing prices, some countries dominated by privately owned land develop public land to build affordable housing and low-rent housing to provide formal and comfortable housing for low- and middle-income families. For instance, the UK requires that every medium-sized community must have a certain amount of low-rent housing; London requires a proportion of low-rent housing as high as 50%. In another case, the Korean government provides 10 to 50-year long-term rent-to-buy housing for families with different income levels [99].

Though the drives for the need for residential land vary in different countries, the formulation of land-use policies plays an important role in the provision of residential land [100]. The formulation of a rational land policy needs to comprehensively consider various contributing factors, and its ultimate goal is to achieve sustainable socio-economic development through government intervention in land use. In addition, the allocation of urban residential land is not only a matter of quantity, but also of quality and spatial distribution. With people’s continuous pursuit of a high quality of life, how to reasonably formulate land-use planning from the quantity, quality and distribution of living space is a challenge for decision-makers [101]. Due to the differences in institutional environments, land-use policies and urban planning in different countries tend to be diversified [102]. Land banking, land adjustment, urban renewal, land agreement assignment, and transfer of development rights, etc., are important instruments of urban land policy. It is worth noting that the formulation of land policy is usually a combination of multiple policy instruments, which requires full recognition of the important contributing factors influencing land supply and demand to continuously adjust and optimize land policy to form the optimal policy design [103].

5. Conclusions

This study proposed a review framework that combines meta-analysis and empirical analysis to identify the general and special contributing factors influencing the allocation of urban residential land. The contributing factors were initially obtained by a systematic review of publications, and frequency analysis was employed to further determine the general contributing factors. Then, the specific contributing factors affecting allocation of urban residential land in different types of countries were determined. Finally, this study collected statistical data from China and Norway, and applied regression analysis to verify the rationality of general contributing factors.

The results of this study showed that population, house price, income, rent, mortgage loan, investment, the number of affordable houses, GDP, employment, housing stock and migration are the general contributing factors that many countries have considered in urban residential land allocation. The correlation analysis results further indicate that the general contributing factors have a positive impact on the supply of urban residential land. Moreover, some specific contributing factors significantly affect the allocation of urban residential land in different types of countries.

Due to UMI countries being generally in the stage of rapid urbanization, the difference in urbanization level has become an important contributing factor that must be considered in the allocation of residential land. In LI countries, poverty alleviation was the primely development goal. Extreme poverty has caused poor infrastructure, loose building construction management systems and large numbers and sizes of slums. Therefore, poverty, infrastructure, the number of informal houses and the number and size of slums were specific contributing factors considered by most LI countries. The good financial and living environment of advanced economies has attracted a large influx of population from developing countries. Therefore, immigration and housing rent were important factors affecting allocation of urban residential land in HI countries.

Countries with ultra-high population densities faced the urgent challenge of a shortage of residential land, forcing them to use every inch of land more efficiently. In such countries, government intervention, the number of households, and the number of affordable houses were important factors that needed to be considered in the allocation of urban residential land. The number of households and the number of affordable houses were also important contributing factors that most HPD countries considered. Housing stock and mortgage loan were contributing factors affecting the allocation of urban residential land in most LMPD and LPD countries.

The results of this study showed that although the contributing factors influencing urban residential land allocation are basically the same in countries with different land ownership structures, the importance of some contributing factors varies in different countries. Employment, housing subsidies, and taxes were contributing factors considered by most countries dominated by privately-owned land. Land-use regulation and building permits and control plays a critical role in the allocation of urban residential land in countries dominated by state-owned land.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and K.W.; methodology, J.Z. and K.W.; software, K.W.; validation, K.W. and W.G.; formal analysis, K.W. and W.G.; data curation, K.W. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.W.; writing—review and editing, K.W. and J.Z.; visualization, K.W. and Z.X.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Funds for Information Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellis, E.C. Sharing the land between nature and people. Science 2019, 364, 1226–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouzols, F.M.; Toivonen, T.; Di Minin, E.; Kukkala, A.S.; Kullberg, P.; Kuusterä, J.; Lehtomäki, J.; Tenkanen, H.; Verburg, P.H.; Moilanen, A. Global protected area expansion is compromised by projected land-use and parochialism. Nature 2014, 516, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Bryan, B.A. Finding pathways to national-scale land-sector sustainability. Nature 2017, 544, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, G.C.; Niu, L. Demand and supply for residential housing in urban China. J. Financ. Res. 2010, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-L.; Yeh, C.-T.; Chang, L.-F. The transition to an urbanizing world and the demand for natural resources. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, X. Land use regulation and urban land value: Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A.; Heathcote, J. The price and quantity of residential land in the United States. J. Monet. Econ. 2007, 54, 2595–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, T. Housing Investment and Residential Land Supply in Japan: An Asset Market Approach. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 1997, 11, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Land and Housing Supply Indicators; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/research/land-and-housing-supply-indicators (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Bradley, Q. The financialisation of housing land supply in England. Urban Studies 2021, 58, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, A.; Berry, J.; McGreal, W. Land availability, housing demand and the property market. J. Prop. Res. 1991, 8, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Soo, J.A. Development conditions and supply of housing: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2002, 128, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.M.; Chui, C.K. Land Development in Hong Kong: To Conserve or not to Conserve? That’s not the Question. In Land and Housing Controversies in Hong Kong: Perspectives of Justice and Social Values; Yung, B., Yu, K.-P., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Empirical Estimate the Different Impact of Landing Price on Housing Among Regions—Based on the Survey Data From Ministry of Land and Resources. South China J. Econ. 2011, 3, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Thibodeau, T.G. Government Interference and the Efficiency of the Land Market in China. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2012, 45, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tian, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Hou, D. Supplying social infrastructure land for satisfying public needs or leasing residential land? A study of local government choices in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A. Constraints affecting the efficiency of the urban residential land market in developing countries: A case study of India. Habitat Int. 2002, 26, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Sloan, M. A framework & dynamic model for reform of residential land supply policy in urban China. Habitat Int. 2018, 82, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, C.Y. Tenure choice and housing demand in Japan. J. Urban Econ. 1988, 24, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, S.A.; Zayed, N.M.; Faisal-E-Alam, M.; Salah Uddin, M.; Nitsenko, V.; Klius, Y. Factors Affecting Demand and Supply in the Housing Market: A Study on Three Major Cities in Turkey. Computation 2022, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, W.; Van Ommeren, J. Housing Supply and the Interaction of Regional Population and Employment; CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G. Measuring Planning: Indicators of Planning Restraint and its Impact on Housing Land Supply. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1998, 25, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajari, P.; Chan, P.; Krueger, D.; Miller, D. A Dynamic Model of Housing Demand: Estimation and Policy Implications. Int. Econ. Rev. 2013, 54, 409–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, J. Deconcentration by Demolition: Public Housing, Poverty, and Urban Policy. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2002, 20, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, S.; Whitehead, C.M.E. Land supply and housing: A case-study. Hous. Stud. 1996, 11, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M.; Allen, M.; Mary, S. The Economic Theory of Housing Demand: A Critical Review. J. Real Estate Res. 1991, 6, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; John, A.A. Macroeconomics: Theory through Applications. Saylor Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haneveld, M.K.; Kragt, J.; Driessen, J. The Price Responsiveness of Housing Supply in the Netherlands. Master’s Thesis, Tilburg School of Economics and Management, Tilburg, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.-H.; Wong, S.K.K.; Cheung, K.S. Land supply and housing prices in Hong Kong: The political economy of urban land policy. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2016, 34, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.C. Housing affordability, self-occupancy housing demand and housing price dynamics. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.S.; Schmidt-Dengler, P.; Felderer, B.; Helmenstein, C. Austrian Demography and Housing Demand: Is There a Connection. Empirica 2001, 28, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.-F.; Trost, R.P. Estimation of some limited dependent variable models with application to housing demand. J. Econom. 1978, 8, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagochi John, M.; Mace Lesley, M. The determinants of demand for single family housing in Alabama urbanized areas. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2009, 2, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accetturo, A.; Lamorgese, A.R.; Mocetti, S.; Pellegrino, D. Housing supply elasticity and growth: Evidence from Italian cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 21, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, P.; Tajani, F.; Anelli, D. Urban planning variants: A model for the division of the activated “plusvalue” between public and private subjects [Interventi in variante urbanistica: Un modello per la ripartizione tra pubblico e privato del “plusvalore” conseguibile]. Valori Valutazioni 2021, 28, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.A. Promoting the supply of low income rental housing. Urban Policy Res. 2001, 19, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.-Y.; Lee, D.; Cheong, A.; Phoon, K.-F.; Wee, K. Housing policies in Singapore: Evaluation of recent proposals and recommendations for reform. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2014, 59, 1450025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.W. Chapter 42 The land market and government intervention. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1637–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu, D. Housing supply under different economic development strategies and the forms of state intervention: The experience of Turkey. Habitat Int. 1996, 20, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R. The effect of land use regulation on housing and land prices. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tang, Y. Residential land use regulation and the US housing price cycle between 2000 and 2009. J. Urban Econ. 2012, 71, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.J.; Somerville, C.T. Land use regulation and new construction. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2000, 30, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G. The Impact of Land Use Planning and Tax Subsidies on the Supply and Price of Housing in Britain. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goytia, C.; de Mendoza, C.; Pasquini, R. Land Regulation in the Urban Agglomerates of Argentina and Its Relationship with Households’ Residential Tenure Condition; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Ma, W. Government intervention in city development of China: A tool of land supply. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K. Government Land Use Interventions: An Economic Analysis. In Urban Land Markets: Improving Land Management for Successful Urbanization; Lall, S.V., Freire, M., Yuen, B., Rajack, R., Helluin, J.-J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Green, K.P.; Filipowicz, J.; Lafleur, S.; Herzog, I. The Impact of Land-Use Regulation on Housing Supply in Canada; Fraser Institute Vancouver: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grzeskowiak, S.; Su, C. Explaining housing preference and choice: The role of self-congruity and functional congruity. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2005, 20, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinas, B.Z.; Jusan, M.B.M. Housing Choice and Preference: Theory and Measurement. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodilin, K.A. Quantifying a century of state intervention in rental housing in Germany. Urban Res. Pract. 2017, 10, 267–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigtländer, M. Why is the German homeownership rate so low? Hous. Stud. 2009, 24, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzien, V.; Rottke, N.; Zietz, J. Affordability and Germany’s low homeownership rate. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2012, 5, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A.; Heiss, F.; Seko, M. Housing Demand in Germany and Japan. J. Hous. Econ. 2001, 10, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Shang, Y.; Wen, H.; Ye, J. Housing Price, Housing Rent, and Rent-Price Ratio: Evidence from 30 Cities in China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 04017026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Do educational facilities affect housing price? An empirical study in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Housing Markets, Government Behaviors, and Housing Choice: A Case Study of Three Cities in China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2004, 36, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. Foreign Investment in Real Estate in Canada: Key Issues; China Institute, University of Alberta: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D.; Koh, S.Y. The globalisation of real estate: The politics and practice of foreign real estate investment. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2017, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmans, C.; Worzala, E. International direct real estate investment: A review of the literature. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1081–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijskens, R.; Lohuis, M. The housing market in major Dutch cities. In Hot Property; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Morano, P.; Tajani, F.; Guarnaccia, C.; Anelli, D. An Optimization Decision Support Model for Sustainable Urban Regeneration Investments. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadegan, M.H.; Fathi, H.; Zamanian, R. Using Strategic Choice Approach in Urban Regeneration Planning (Case Study: Dolatkhah Area in Tehran, Iran). Int. J. Archit. Urban Dev. 2014, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gyourko, J.; Saks, R.E. Urban growth and housing supply. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-M.; Xu, H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Men, M.-X.; Ji, W.-G. Research on the method of forecasting annual urban residential land supply. J. Agric. Univ. Hebei 2007, 4, 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, R.Y.; Ho, C.; Ganesan, S. Matching housing supply and demand: An empirical study of Hong Kong’s market. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1999, 17, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, H.G.; Puga, D.; Turner, M.A. Decomposing the growth in residential land in the United States. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2008, 38, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldera, A.; Johansson, Å. The price responsiveness of housing supply in OECD countries. J. Hous. Econ. 2013, 22, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serin, B. Reviewing the Housing Supply Literature: A Literature Mapping; UK Collaborative Center for Housing Evidence: Glasgow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Chen, Q.; Tang, B.-S.; Yeung, S.; Hu, Y.; Cheung, G. A system dynamics model for the sustainable land use planning and development. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, S.; Gould, W.A.; Ramos González, O.M. Land development, land use, and urban sprawl in Puerto Rico integrating remote sensing and population census data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, C. The Modern State; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Z.; Felsenstein, D. Supply side constraints in the Israeli housing market—The impact of state owned land. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarland, K.; Reid, C.K. Homeownership and residential stability: Does tenure really make a difference? Int. J. Hous. Policy 2019, 19, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, J.; Langhorst, J. Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land. Cities 2014, 40, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Miller, P.A.; Nowak, D.J. Urban vacant land typology: A tool for managing urban vacant land. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Feeny, D. Land tenure and property rights: Theory and implications for development policy. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1991, 5, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkaia, C.; Rudaib, Y. Land supply, housing price and household saving in urban China: Evidence from urban household survey. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 1, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, S.; Pearce, B.; Whitehead, C.M. Land-use planning, land supply, and house prices. Environ. Plan. A 1996, 28, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aura, S.; Davidoff, T. Supply constraints and housing prices. Econ. Lett. 2008, 99, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Qian, Z. State Intervention in Land Supply and Its Impact on Real Estate Investment in China: Evidence from Prefecture-Level Cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnley, I.H. Immigration and Housing in an Emerging Global City, Sydney, Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2005, 23, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.; McDonald, P. International migration and the growth of households in Sydney. People Place 2003, 11, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard, C. International Migration, Housing Demand and Access to Homeownership in the UK. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 2211–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Albis, H.; Boubtane, E.; Coulibaly, D. International Migration and Regional Housing Markets: Evidence from France. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2018, 42, 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Chokani, N.; Abhari, R.S. Immigration and future housing needs in Switzerland: Agent-based modelling of agglomeration Lausanne. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 78, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, J.E.; Paterson, R.W. The effects of critical habitat designation on housing supply: An analysis of California housing construction activity. J. Reg. Sci. 2006, 46, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A. Housing supply in Delhi. Cities 2003, 20, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, J.; Taubenböck, H.; Wurm, M.; Pelz, P.F. The similar size of slums. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni-Jimoh, T.; Liyanage, C.; Oyebanji, A.; Gerges, M. Urbanization and meeting the need for affordable housing in Nigeria. Hous. Amjad Almusaed Asaad Almssad IntechOpen 2018, 7, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamete, A.Y. Revisiting the urban housing crisis in Zimbabwe: Some forgotten dimensions? Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenla, M.; Gonzalez, F. Housing demand in Mexico. J. Hous. Econ. 2009, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.-Y. House prices and aggregate consumption: Do they move together? Evidence from Singapore. J. Hous. Econ. 2004, 13, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, R.; Haberzettl, P.; Walsh, R.P.D. Land reclamation in Singapore, Hong Kong and Macau. GeoJournal 1991, 24, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. Exploring the relationship between urban land supply and housing stock: Evidence from 35 cities in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.-C.; Yap, A. From universal public housing to meeting the increasing aspiration for private housing in Singapore. Habitat Int. 2003, 27, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Jiangang, S. Chinese local Government’s behavior in land supply in the context of housing market macro-control. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2017, 20, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Ge, X.J.; Wu, Q. Government intervention in land market and its impacts on land supply and new housing supply: Evidence from major Chinese markets. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.-Y.; Lee, S.-J. Korean Public Rental Housing for Low-income Households: Main Outcome and Limitations. LHI J. Land Hous. Urban Aff. 2013, 4, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davy, B. Land Policy: Planning and the Spatial Consequences of Property; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, S.; Hartmann, T.; Jonkman, A. Strategies of municipal land policies: Housing development in Germany, Belgium, and Netherlands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 1132–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Jehling, M. From diversity to justice—Unraveling pluralistic rationalities in urban design. Cities 2019, 91, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Introduction: Understanding integrated policy strategies and their evolution. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).