Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Participatory Planning

2.2. Public Participation

2.3. Rural Planning and Rural Landscape Design

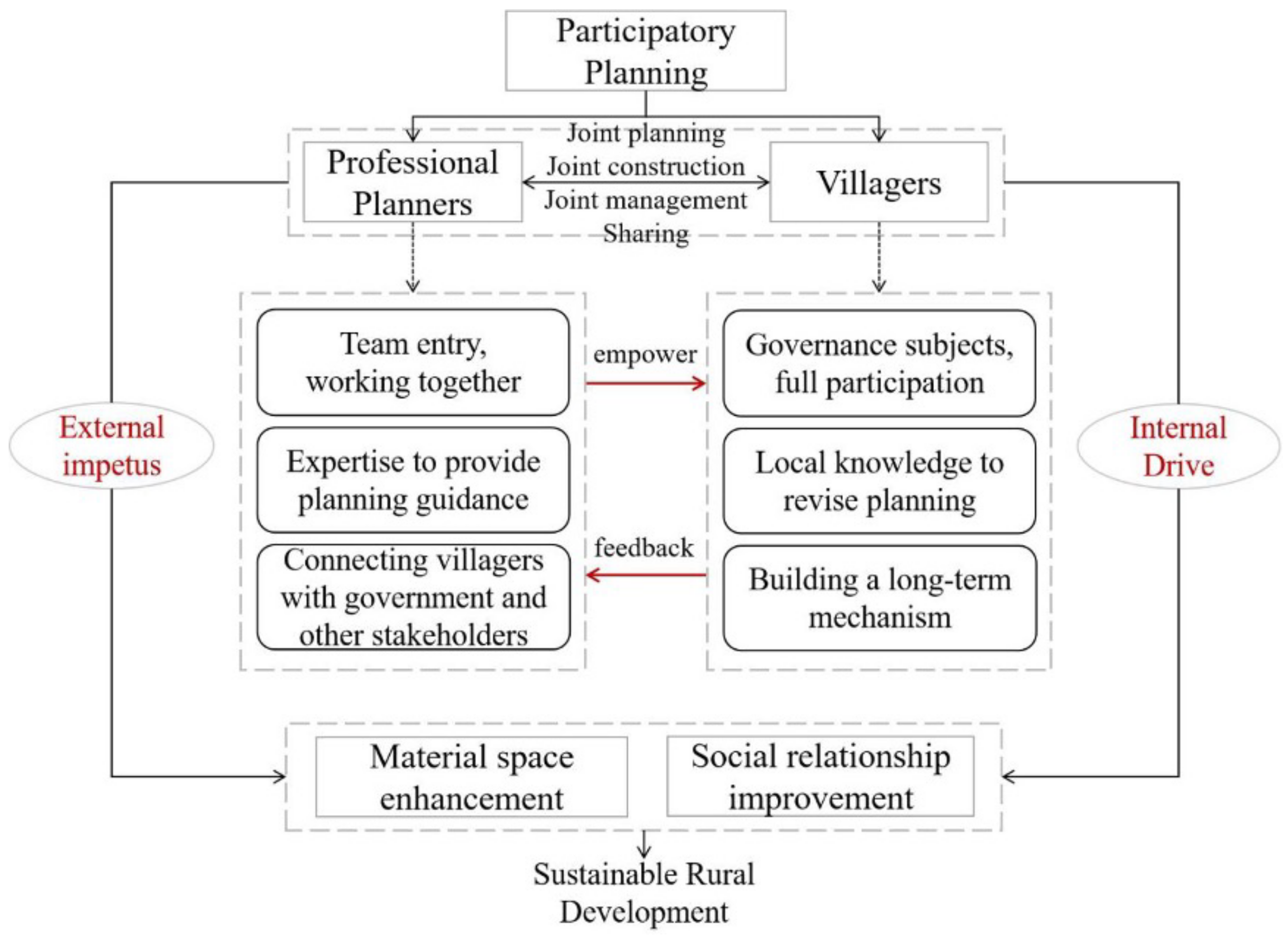

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Role of Planning Professionals

3.2. Villagers Participating in Self-Governance

3.3. Participatory Planning Framework

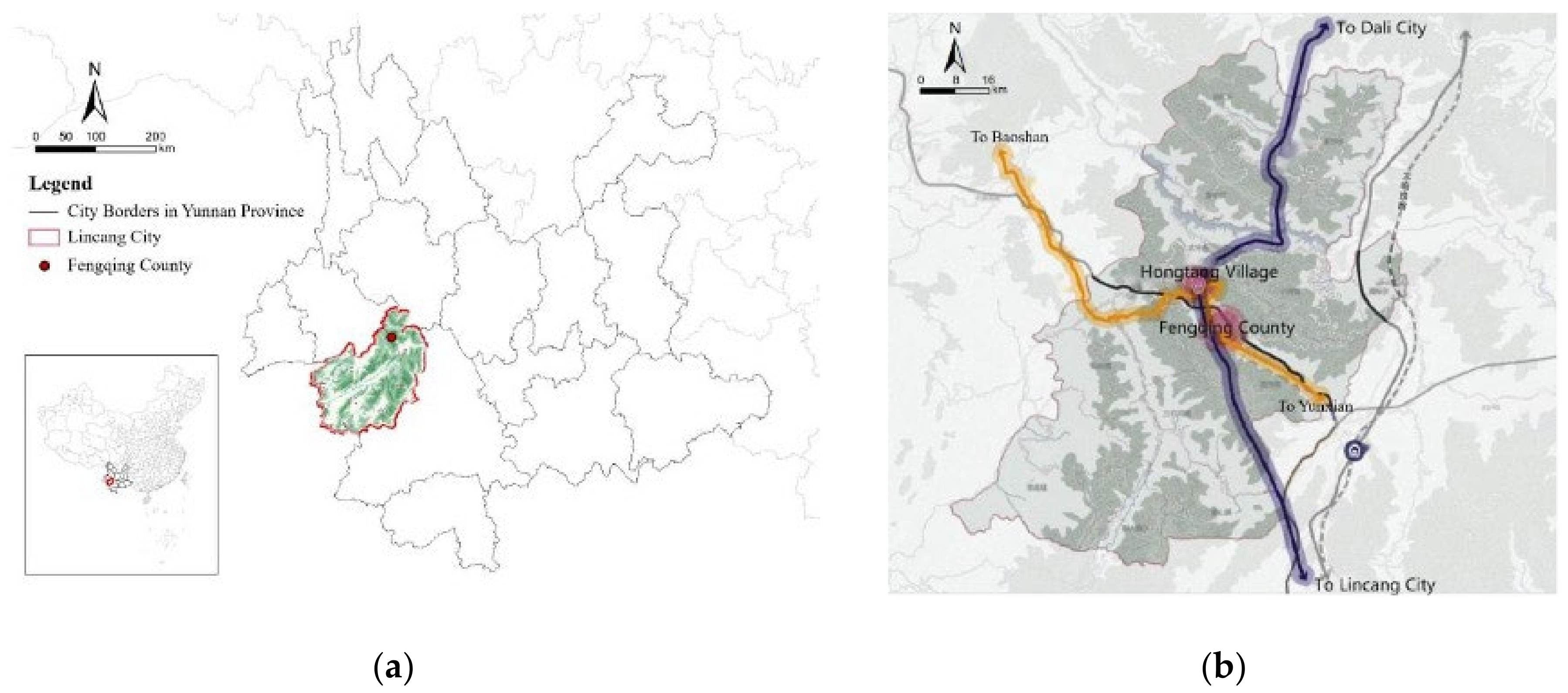

4. An Empirical Study in Fengqing Country, China

4.1. The Study Area of Hongtang Village

4.2. Building a Rural Yard through Participatory Planning

4.3. The Interaction Process between Professional Planners and the Villagers

4.3.1. Planning Intervention: Assist Villagers in Participating and Developing Local Knowledge

4.3.2. Villager Empowerment: Improve Participation Ability and Form an Interactive Mechanism

5. Discussion and Implication

5.1. Building a New Approach for Rural Planning in China

5.2. Suggestions on Strategies for Rural Planning Practice

5.3. Recommendations for Building a Sustainable Rural Community

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedmann, J. Regional Development Policy: A Case Study of Venezuela; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, W. Industrial Location and Regional Policy in Economic Development. 1968. Available online: https://open.unido.org/api/documents/4685649/download/INDUSTRIAL%20LOCATION%20AND%20REGIONAL%20DEVELOPMENT%20-%20THE%20GENERAL%20PROBLEM%20(02502d.en) (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Benedek, J. The Role of Urban Growth Poles in Regional Policy: The Romanian Case. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Potter, R.B.; Unwin, T. (Eds.) The Geography of Urban-Rural Interaction in Developing Countries: Essays for Alan B. Mountjoy; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.M. Unpredictable Directions of Rural Population Growth and Migration. In Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century; The Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Milbourne, P. Re-Populating Rural Studies: Migrations, Movements and Mobilities. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. The Changing Faces of Rural Populations: ‘“(Re) Fixing” the Gaze’ or ‘Eyes Wide Shut’? J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, M.; Lundholm, E. Restructuring of Rural Sweden—Employment Transition and out-Migration of Three Cohorts Born 1945–1980. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.; Walmsley, J.; Argent, N.; Baum, S.; Bourke, L.; Martin, J.; Pritchard, B.; Sorensen, T. Rural Community and Rural Resilience: What Is Important to Farmers in Keeping Their Country Towns Alive? J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Swanson, L.E. Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century; Penn State Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, S.; Halseth, G.; Manson, D. Challenging the Inevitability of Rural Decline: Advancing the Policy of Place in Northern British Columbia. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Results of the World Conference on Environment and Development: Agenda 21. In Proceedings of the UNCED—United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sicular, T.; Ximing, Y.; Gustafsson, B.; Li, S. The Urban-Rural Income Gap and Income Inequality in China. In Understanding Inequality and Poverty in China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 30–71. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of The People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China in 2021. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/shuju/2022-02/28/content_5676015.htm (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Long, H.; Zou, J.; Pykett, J.; Li, Y. Analysis of Rural Transformation Development in China since the Turn of the New Millennium. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H. Rural Restructuring in China: Theory, Approaches and Research Prospect. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, H.; Liao, L.; Tu, S.; Li, T. Land Use Transitions and Urban-Rural Integrated Development: Theoretical Framework and China’s Evidence. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Li, X. Exploring the Impact of Urban Green Space on Residents’ Health in Guangzhou, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 146, 05019022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of Urban-Rural Integration Level and Its Spatial Differentiation in China in the New Century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Sui, X.; Ye, B.; Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Zou, M.; Zhou, S. What Role Does Land Consolidation Play in the Multi-Dimensional Rural Revitalization in China? A Research Synthesis. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural Restructuring at Village Level under Rapid Urbanization in Metropolitan Suburbs of China and Its Implications for Innovations in Land Use Policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Tu, S. Multi-Scale Analysis of Rural Housing Land Transition under China’s Rapid Urbanization: The Case of Bohai Rim. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s Rural Revitalization and Development: Theory, Technology and Management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W.; Tao, L. People, recreational facility and physical activity: New-type urbanization planning for the healthy communities in China. Habitat Int. 2016, 58, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerson, M.; Banfield, E.C. Politics, Planning, and the Public Interest: The Case of Public Housing in Chicago; Free Press of Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Communication and the Evolution of Society; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E. Planning Theory’s Emerging Paradigm: Communicative Action and Interactive Practice. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1995, 14, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory and Its Implications for Spatial Strategy Formation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 1996, 23, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1965, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monno, V.; Khakee, A. Tokenism or Political Activism? Some Reflections on Participatory Planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2012, 17, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E. Information in Communicative Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1998, 64, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffikin, F.; Morrissey, M. Planning in Divided Cities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E. Consensus Building: Clarifications for the Critics. Plan. Theory 2004, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- And, S.G.; Heskin, A. Foundations for a Radical Concept of Planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1973, 39, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Toward a Non-Euclidian Mode of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1993, 59, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, L.; Bridgman, R. Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities. Can. J. Urban Res. 1999, 8, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L.; Lyssiotis, P. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities of the 21st Century; A&C Black: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, M.M. A Difference Paradigm for Planning. In Planning Theory in the 1980s: A Search for Future Directions; Center for Urban Policy Research: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1978; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tayebi, A. Planning Activism: Using Social Media to Claim Marginalized Citizens’ Right to the City. Cities 2013, 32, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A New Style of Urbanization in China: Transformation of Urban Rural Communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slotterback, C.S.; Lauria, M. Building a Foundation for Public Engagement in Planning: 50 Years of Impact, Interpretation, and Inspiration From Arnstein’s Ladder. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guldin, G.E. Farewell to Peasant China: Rural Urbanization and Social Change in the Late Twentieth Century; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Resolving Social Conflicts and Field Theory in Social Science.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.P. The Community in Rural America; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, B. The Rural Context of Community Development in Canada. J. Rural Community Dev. 2006, 1, 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, B.; Lyons, T.; Ferguson, N.; Polanco, G. Social Capital as Social Relations: The Contribution of Normative Structures. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 56, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a Multifunctional Transition in Rural Australia: Gaps in the Research Agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Rural Pact—Proposals from the Rural Pact Preparatory Group for the Rural Pact Conference on 15–16 June 2022. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-07/rural-pact-proposal_en.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, N.J. Place-Based Public Policy: Towards a New Urban and Community Agenda for Canada; Canadian Policy Research Networks, Work Network: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Konečný, O. The Leader Approach Across The European Union: One Method of Rural Development, Many Forms of Implementation. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P. Key Settlements in Rural Areas (Routledge Revivals); Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, K.; Burdess, N. New Community Governance in Small Rural Towns: The Australian Experience. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiepoh, M.G.N.; Reimer, B. Social Capital, Information Flows, and Income Creation in Rural Canada: A Cross-Community Analysis. J. Socio-Econ. 2004, 33, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woolcock, M. The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes. Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, B.; Bollman, R.D. Understanding Rural Canada: Implications for Rural Development Policy and Rural Planning Policy. 2010; p. 43. Available online: https://2018.icrps.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/06/Reimer-Bollman-2010-Understanding-Rural-Canada.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Knight, J. Rural Kokusaika? Foreign Motifs and Village Revival in Japan. Jpn. Forum 1993, 5, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.; Maye, D.; Pearson, D. Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, N.; Simpson, T.; Orlove, B.; Dowd-Uribe, B. Environmental and social dimensions of community gardens in East Harlem. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 183, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P.; Sanchez, E.L. Cultivating Community: Perceptions of Community Garden and Reasons for Participating in a Rural Victorian Town. Act. Adapt. Aging 2018, 42, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, M. The Countryside Ideal: Anglo-American Images of Landscape; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, K.H. Locality and Social Representation: Space, Discourse and Alternative Definitions of the Rural. In The Rural; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, C.E.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.; Zhao, P.J.; Zhang, X.C.; Tu, L. Study on the public participation model of farmers in rural planning in China in the new era. Mod. Urban Res. 2015, 4, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, D. Authority, Gender and Knowledge: Theoretical Reflections on the Practice of Participatory Rural Appraisal. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H.; Lane, M.B.; Hibbard, M. Planning, Governance and Rural Futures in Australia and the USA: Revisiting the Case for Rural Regional Planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 1601–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J. Planning through Consensus Building: A New View of the Comprehensive Planning Ideal. In Classic Readings in Urban Planning; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Njoh, A.J. Municipal Councils, International NGOs and Citizen Participation in Public Infrastructure Development in Rural Settlements in Cameroon. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junbo, W. Evolution Mechanism, History And Characteristics Of China’s Rural Areas Since The Reform And Opening-Up; WIT Press: Ashurst, UK, 2022; pp. 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riristuningsia, D.W.; Harsono, I. Public Participation in Rural Development Planning (A Study in Lopok Village, Lopok District, Sumbawa Regency—West Nusa Tenggara). JESP 2017, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plummer, J.; Taylor, J.G. Community Participation in China: Issues and Processes for Capacity Building; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, P.; Townsend, L.; Salemink, K. Smart Rural Futures: Will Rural Areas Be Left behind in the 4th Industrial Revolution? J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond Government-Led or Community-Based: Exploring the Governance Structure and Operating Models for Reconstructing China’s Hollowed Villages. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. Urban Regeneration Involving Communication between University Students and Residents: A Case Study on the Student Village Design Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodorkós, B.; Pataki, G. Linking Academic and Local Knowledge: Community-Based Research and Service Learning for Sustainable Rural Development in Hungary. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlöv, H. Village Government and Rural Development in Indonesia: The New Democratic Framework. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2003, 39, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, A.; Sanders, E.B.N. A collaboration system model for planning and evaluating participatory design projects. Int. J. Des. 2019, 13, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the “three old renewals” in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.C.; Tisdell, C.A. Good Governance in Sustainable Development: The Impact of Institutions. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1998, 25, 1310–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Productivism and Post-Productivism: An Analysis of Functional Mixtures in Rural China. Land 2022, 11, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hui, E.C.; Zhou, J.; Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. Rural revitalization in China: Land-use optimization through the practice of place-making. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I. A Framework for Revitalisation of Rural Education and Training Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: Strengthening the Human Resource Base for Food Security and Sustainable Livelihoods. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2007, 27, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Tan, S.; Lang, W.; Chen, T. Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China. Land 2023, 12, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010187

Yan J, Huang Y, Tan S, Lang W, Chen T. Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China. Land. 2023; 12(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Jialing, Yan Huang, Shuying Tan, Wei Lang, and Tingting Chen. 2023. "Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China" Land 12, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010187

APA StyleYan, J., Huang, Y., Tan, S., Lang, W., & Chen, T. (2023). Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China. Land, 12(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010187