A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. Data Sources

3. Results

3.1. Number of Published Papers and Publication Trend

3.2. Author Cooperation Network

3.3. Analysis of Research Institution Collaboration Networks

3.4. Analysis of Keywords

3.4.1. Keyword Centrality Analysis

- (1)

- Degree centrality

- (2)

- Betweenness centrality

3.4.2. Keywords Cluster Analysis

3.5. Burst Keywords

4. Discussion

4.1. Progress of CFC Construction and Research Topics Are Related to the Level of Economic Development of the City

4.2. The Significant Role of Multi-Party Cooperation in Policy Implementation and Child Participation

4.3. Different Focus in Environmental Research

4.4. Diversifying Avenues for Child Participation

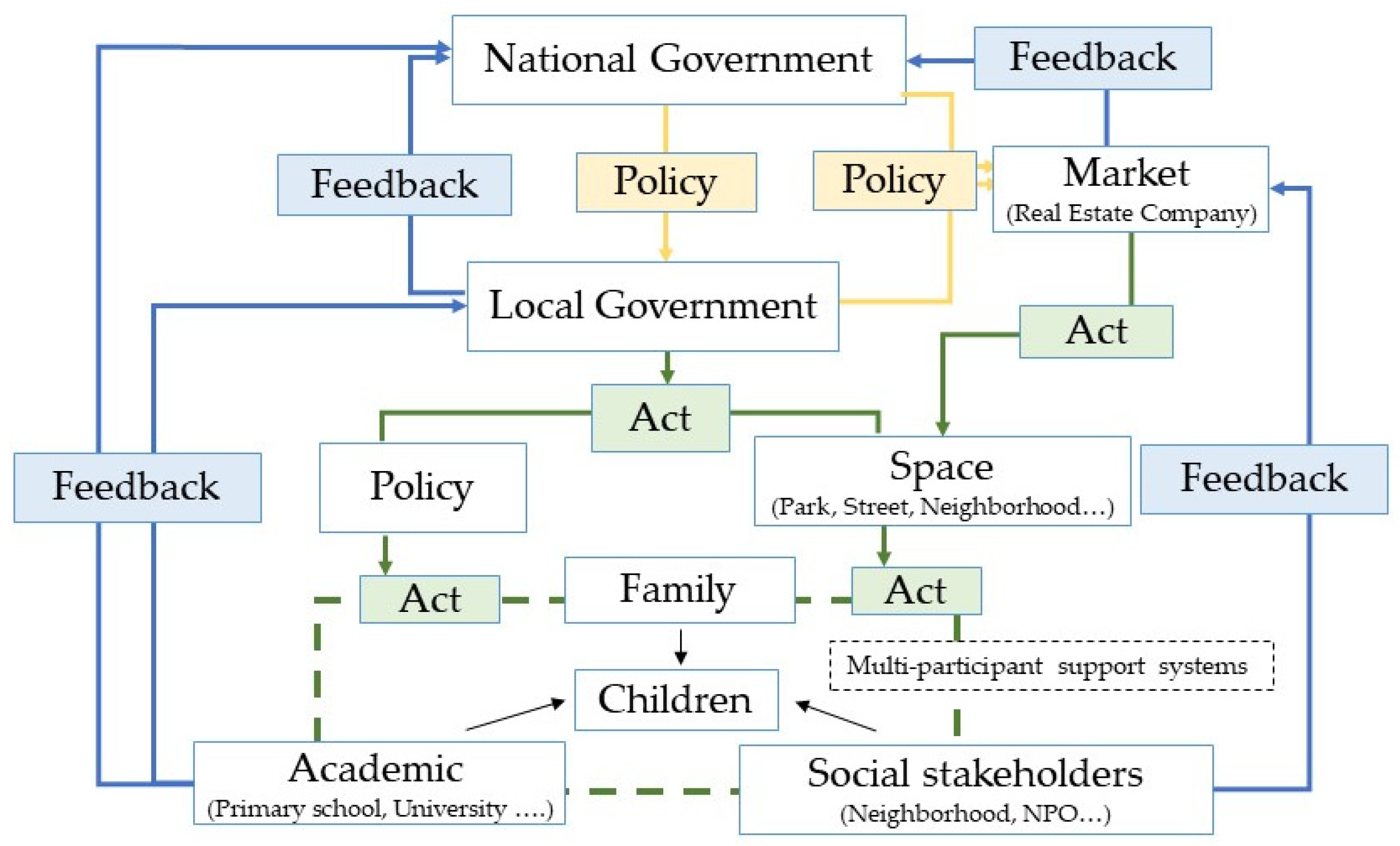

4.5. Proposed Conceptual Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Details of the Data Retrieval Criteria and Results

| Query 1 | Query 2 | Query 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Database | Web of Science Core Collection | ||

| Search time frame | 2000.1.1–2022.12.31 | ||

| Query String | (((TS = (child-friendly city)) OR TS = (child friendly city)) OR TS = (child-friendly cities)) OR TS = (child friendly cities) | (TS = (“child-friendly” OR “child friendly”)) AND TS = (“city” OR “cities” OR “community” OR “communities” OR “urban” OR “rural” OR “public space” OR “public spaces” OR “open space” OR “open spaces” OR “green space” OR “green spaces” OR “park” OR “parks” OR “playground” OR “playgrounds”) | (TS = (“child friendly” OR “child-friendly” OR “child participation” OR “child-participation” OR “children’s participation”)) AND TS = (“urban planning” OR “city planning” OR “town planning” OR “regional planning” OR “urban design” OR “traffic planning” OR “transportation planning” OR “spatial planning” OR “planning strategies” OR “planning strategy” OR “design strategies” OR “design strategy” OR “urban governance” OR “city construction” OR “ city constructions” OR “urban construction” OR “urban constructions”) |

| Research Area | Environmental Sciences Ecology or Psychology or Sociology or Behavioral Sciences or Urban Studies or Geography or Social Sciences Other Topics or Public Administration or Demography or Family Studies or Psychiatry or Social Issues or Transportation or Architecture or Social Work or Forestry | Environmental Sciences Ecology or Psychology or Sociology or Geography or Behavioral Sciences or Urban Studies or Social Sciences Other Topics or Family Studies or Social Issues or Public Administration or Social Work or Architecture or Psychiatry | Environmental Sciences Ecology or Geography or Urban Studies or Sociology or Public Administration or Social Sciences Other Topics or Public Environmental Occupational Health or Social Issues or Architecture |

| Language | En | ||

| Search results | 290 | 241 | 54 |

| Final records | 265 | ||

| Query 1 | Query 2 | Query 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Database | CNKI Core Collection | ||

| Search time frame | 2000.1.1–2022.12.31 | ||

| Query String | 主题 = 儿童友好城市 TS = (child-friendly city) | 主题 = (儿童友好 + 儿童参与 (精确)) * (城市 + 社区 + 乡镇 +区域 + 空间 + 设计 + 规划 + 绿地 + 开放空间 (精确)) (TS = (“child-friendly” OR “child-participation”)) AND TS= (“city” OR “community” OR “rural” OR “region” OR “space” OR “design” OR “plan” OR “green space” OR “open space”) | 主题 = (儿童友好 + 儿童参与) * (规划 + 设计 + 布局) * (建成环境 + 建筑 + 绿地 + 绿地空间 + 绿地系统 + 公园 + 绿化 + 开放空间 + 绿色 + 生态 + 开敞空间 + 经济 + 公共空间 + 慢行交通 + 步行 + TOD + 城市道路) (TS = (“child-friendly” OR “child-participation”)) AND TS = (“plan” OR “design” OR “layout”) AND TS = (“built environment” OR “building” OR “green space” OR “green field” OR “green space system” OR “park” OR “green” OR “ecosystem” OR “open space” OR “non-motorized transportation” OR “walking” OR “TOD” OR “urban road”) |

| Research Area | 建筑工程 (Architecture and Engineering) | ||

| Language | CHN | ||

| Search results | 191 | 761 | 250 |

| Final records | 654 | ||

Appendix B. Glossary of Chinese Terms and Translation

| Position in Article | English Term | Chinese Term |

| Figure 9 | Child-friendly city | 儿童友好城市 |

| Figure 9 | Child-friendly | 儿童友好 |

| Figure 9 | Child participation | 儿童参与 |

| Figure 9 | Children | 儿童 |

| Figure 9 | Child-friendly type | 儿童友好型 |

| Figure 9 | Public space | 公共空间 |

| Figure 9 | Child health | 儿童保健 |

| Figure 9 | Community | 社区 |

| Figure 9 | Children’s rights | 儿童权利 |

| Figure 9 | Child-friendly community | 儿童友好社区 |

| Figure 9 | Health education | 健康教育 |

| Figure 9 | Landscape architecture | 风景园林 |

| Figure 9 | Landscape design | 景观设计 |

| Figure 9 | Children’s activity space | 儿童活动空间 |

| Figure 9 | Child-friendly community | 儿童友好型社区 |

| Figure 9 | Planning and design | 规划设计 |

| Figure 9 | Participatory design | 参与式设计 |

| Figure 9 | Mobile children | 流动儿童 |

| Figure 9 | Open space | 开放空间 |

| Figure 9 | Outdoor activity space | 户外活动空间 |

| Figure 9 | United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | 联合国儿童基金会 |

| Figure 9 | Space design | 空间设计 |

| Figure 9 | Urban space | 城市空间 |

| Figure 9 | Community public space | 社区公共空间 |

| Figure 9 | Urban renewal | 城市更新 |

| Figure 9 | Play space | 游戏空间 |

| Figure 9 | Shenzhen City | 深圳市 |

| Figure 9 | Urban public space | 城市公共空间 |

| Figure 9 | Urban planning | 城市规划 |

| Figure 9 | Community parents of infants | 社区婴儿家长 |

| Figure 9 | United States | 美国 |

| Figure 9 | Residential area | 居住区 |

| Figure 9 | Space | 空间 |

| Figure 9 | Design strategy | 设计策略 |

| Figure 9 | Kindergarten | 幼儿园 |

| Figure 9 | Community planning | 社区规划 |

| Figure 9 | Left-behind children in rural areas | 农村留守儿童 |

| Figure 9 | Urban park | 城市公园 |

| Figure 9 | Old communities | 老旧社区 |

| Figure 9 | Community children | 社区儿童 |

| Figure 9 | One-year-old child | 1岁小儿 |

| Figure 9 | Community development | 社区建设 |

| Figure 9 | Child welfare | 儿童福利 |

| Figure 9 | Children’s play space | 儿童游戏空间 |

| Figure 9 | Parents of infants | 婴儿家长 |

| Figure 9 | Public participation | 公众参与 |

| Figure 9 | Parental involvement | 家长参与 |

| Figure 9 | Community renewal | 社区更新 |

| Figure 9 | Street design | 街道设计 |

| Figure 9 | Community garden | 社区花园 |

| Figure 9 | Community governance | 社区治理 |

| Figure 9 | City | 城市 |

| Figure 9 | Community construction | 社区营造 |

| Figure 9 | Street space | 街道空间 |

| Figure 9 | Participation | 参与 |

| Figure 9 | Strategy | 策略 |

| Figure 9 | Residential area | 住区 |

| Figure 9 | Left-behind children | 留守儿童 |

| Figure 9 | Effect evaluation | 效果评价 |

| Figure 9 | Planning | 规划 |

| Figure 9 | Changsha | 长沙 |

| Figure 9 | Rural revitalization | 乡村振兴 |

| Figure 9 | Optimization strategy | 优化策略 |

| Figure 9 | Social organization | 社会组织 |

| Figure 9 | Guangzhou | 广州 |

References

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children in an Urban World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-92-1-059758-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, S. Study on Urban Public Space Planning Strategy Based on Child-Friendly City Theory: Taking Public Opinion Surveys and Case Studies in Yueyang and Changsha as Examples. City Plan. Rev. 2018, 42, 79–86+96. [Google Scholar]

- CFCI Framework|Child-Friendly Cities Initiative. Available online: https://www.childfriendlycities.org/cfci-framework (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Askew, J. Shaping Urbanization for Children: A Handbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planning: By Jens Aerts, New York, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2018, 188 pp., ISBN: 978-92-806-4960-4. Cities Health 2019, 3, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat). An Urbanizing World : Global Report on Human Settlements, 1996; Oxford University Press for the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 1996; ISBN 978-0-19-823346-6. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. Planning Practices and Implications on the Overseas Child Friendly Cities. Urban Probl. 2020, 3, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Sundevall, E.; Wales, M. The Role of Green Spaces and Their Management in a Child-Friendly Urban Village. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S.P. How Does The Playground Role in Realizing Children-Friendly-City? Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.E.; Gosselin, V.; Collins, P.; Frohlich, K.L. A Tale of Two Cities: Unpacking the Success and Failure of School Street Interventions in Two Canadian Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geravandi, A. An In-Depth Perspective Analysis for Developing a Social Marketing Model to Promote Female Adolescents’ Participation in Regular Physical Activities: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 15094–15108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, S.; Metzler, J.; Savage, K.; Musa, M.; Ager, A. Child Friendly Spaces Impact across Five Humanitarian Settings: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.; Corkery, L. Designing Cities with Children and Young People: Beyond Playgrounds and Skate Parks; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-317-48776-0. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Shi, N.; He, Y.; Yang, H.; Pan, Y.; Yu, W.; Shen, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wei, L. Practice of Child-Friendly City Construction. City Plan. Rev. 2022, 46, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; He, X.; Cheng, L.; Wang, T. Children’s Recreational Space Planning and Construction in High-density Cities. Planners 2022, 38, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Yun, H.; Zhao, M.; Liu, M. Child Friendly Community Street Environment Construction Strategy. Archit. J. 2020, 2, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, D. The Planning and Design of Child Friendly City Open Space: Enlightenment of the CFC’s Open Space Aboard. Mod. Urban Res. 2014, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cities Changing for Children—Interpretation of Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/jd/202110/t20211028_1301440.html?state=123 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Outline of the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Vision 2035_Scrolling News_China.gov.cn. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, S. Review of Studies about Urban Children’s Demands of Outdoor Space in China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 2, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Review of Foreign Studies About Children’s Demands of Outdoor Public Space in Cities. Urban Plan. Int. 2011, 26, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Shen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Woolley, H. Evaluation Indicators of Children’s Mobility Safety in the Community Environment Based on English Literature Review. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhu, C. Research Progress and Foreign Enlightenment of Domestic Child-friendly Cities. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2022, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Vinueza, V.A.; Niekerk, F.; van Dijk, T. Making Child-Friendly Cities: A Socio-Spatial Literature Review. Cities 2023, 137, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homrich, A.S.; Galvão, G.; Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. The Circular Economy Umbrella: Trends and Gaps on Integrating Pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The Bibliometric Analysis of Scholarly Production: How Great Is the Impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Chen, C. A Scientometric Review of Emerging Trends and New Developments in Recommendation Systems. Scientometrics 2015, 104, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tseng, H. Emerging Trends in Regenerative Medicine: A Scientometric Analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Q. Current Status, Topical Issues, and Trends in China’s Resource and Environmental Economy Research—CiteSpace-based Visual Analysis. Nat. Resour. Econ. China 2023, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X. The methodology function of Cite Space mapping knowledge domains Chinese Full Text. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2015, 33, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Academic Details and Bibliometrics. COOC_A Software Used for Bibliometrics and Knowledge Graph Visualization. Available online: http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU3NDQ2MTI5Mg==&mid=2247499017&idx=1&sn=a5136d40e281bce904fa2ee402a92d1d&chksm=fd30b90aca47301c8d1a0742f74d5244088c7b7f54df5abd8b37d9dcd8c3f30ac949cfd170f7#rd (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Deng, J. Comparative Study of the Social Network Analysis Tools: Ucinet and Gephi. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2014, 37, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Chen, W.; Liang, J.; Li, J. Comparison of Spatial Planning Research at Home and Abroad Based on Bibliometric Analysis. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Mao, L. Evolution of research on Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei cooperative development based on CiteSpace method. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 2378–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Kinoshita, I.; He, L. Study on the Development Characteristics and Re-Developing Direction of Children’s Playing Space in High-Rise Housing Estate. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Tang, H.; Dong, Y.; Liu, K.; Jiang, P.; Liu, Y. Knowledge Mapping of Research on Land Use Change and Food Security: A Visual Analysis Using CiteSpace and VOSviewer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Zhao, X.; Yang, C.; Shi, J. Innovation in the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities in China—The Ecological Construction of the Chinese Children’s Center’s Child-Friendly Educational Complex. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2020, 3, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, E.; Hinckson, E.; Witten, K.; Smith, M. Assessment of Direct and Indirect Associations between Children Active School Travel and Environmental, Household and Child Factors Using Structural Equation Modelling. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.; Smith, M.; Anderson, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Maharaj, S.; Donnellan, N. Improving Spatial Data in Health Geographics: A Practical Approach for Testing Data to Measure Children’s Physical Activity and Food Environments Using Google Street View. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2021, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Ward, K.; Egli, V.; Mandic, S.; Pocock, T.; Clark, T.C.; Smith, M. More-Than-Human: A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring Children’s Perceptions of Health and Health-Promoting Neighbourhoods in Aotearoa New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, K.; Kearns, R.; Carroll, P. Urban Inclusion as Wellbeing: Exploring Children’s Accounts of Confronting Diversity on Inner City Streets. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 133, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, P.; Calder-Dawe, O.; Witten, K.; Asiasiga, L. A Prefigurative Politics of Play in Public Places: Children Claim Their Democratic Right to the City Through Play. Space Cult. 2019, 22, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Witten, K.; Asiasiga, L.; Lin, E.-Y. Children’s Engagement as Urban Researchers and Consultants in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Can It Increase Children’s Effective Participation in Urban Planning? Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Xu, J. Application and Analysis of Social Network Analysis in Review of Aviation Safety Management System (SMS) Research. Adv. Aeronaut. Sci. Eng. 2018, 9, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Chen, Z. Knowledge Map Analysis of Hotspots and Development Trend of Researches on Governance in China—A Visualized Research Based on CSSCI Database 2000–2019. J. Univ. Jinan (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 31, 108–117+159. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chau, K.-Y.; Liu, X.; Wan, Y. The Progress of Smart Elderly Care Research: A Scientometric Analysis Based on CNKI and WOS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Graaf, S. The Right to the City in the Platform Age: Child-Friendly City and Smart City Premises in Contention. Information 2020, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Lin, Y.; Han, C.; Janssen, I.; Schuurman, N.; Boyes, R.; Swanlund, D.; Mâsse, L.C. A Qualitative Investigation of Unsupervised Outdoor Activities for 10- to 13-Year-Old Children: “I like Adventuring but I Don’t like Adventuring without Being Careful”. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, S.; Said, I. Children’s Nomination of Friendly Places in an Urban Neighbourhood in Shiraz, Iran. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, W.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y. Children’s Walking to Urban Services: An Analysis of Pedestrian Access to Social Infrastructures and Its Relationship with Land Use. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2023, 37, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.S.; Roche, S.; Contreras, C.; Del Castillo, H.; Canales, P.; Jimenez, J.; Tintaya, K.; Becerra, M.C.; Lecca, L. Barriers to the Treatment of Childhood Tuberculous Infection and Tuberculosis Disease: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daodu, T.; Said, I. An Appraissal of Independent Mobility towards Advancing Child-Friendly Military Barrack Community Milieu in Developing Countries. E-BPJ 2018, 3, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, M.; Adams, J.G.U. Children’s Freedom and Safety. Child. Environ. 1992, 9, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, H.P.; Merom, D.; Corpuz, G.; Bauman, A.E. Trends in Australian Children Traveling to School 1971–2003: Burning Petrol or Carbohydrates? Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, N.C. Active Transportation to School: Trends Among U.S. Schoolchildren, 1969–2001. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buliung, R.N.; Mitra, R.; Faulkner, G. Active School Transportation in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada: An Exploration of Trends in Space and Time (1986–2006). Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Hirvonen, J.; Rudner, J.; Pirjola, I.; Laatikainen, T. The Last Free-Range Children? Children’s Independent Mobility in Finland in the 1990s and 2010s. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A. Public Space and the Culture of Childhood; Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica; Núm.: 45; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, P.; Witten, K.; Kearns, R.; Donovan, P. Kids in the City: Children’s Use and Experiences of Urban Neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitzman, C.; Mizrachi, D. Creating Child-Friendly High-Rise Environments: Beyond Wastelands and Glasshouses. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Children’s Friendship with Place: A Conceptual Inquiry. Child. Youth Environ. 2005, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, D.G.; Castro Seixas, E. Children’s Green Infrastructure: Children and Their Rights to Nature and the City. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 804535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hecke, L.; Ghekiere, A.; Veitch, J.; Van Dyck, D.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Clarys, P.; Deforche, B. Public Open Space Characteristics Influencing Adolescents’ Use and Physical Activity: A Systematic Literature Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. Health Place 2018, 51, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broberg, A.; Kyttä, M.; Fagerholm, N. Child-Friendly Urban Structures: Bullerby Revisited. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M. The Extent of Children’s Independent Mobility and the Number of Actualized Affordances as Criteria for Child-Friendly Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Chen, S. Research on Impacts of Participatory Community Planning on the Publicity of Public Space Based on Child-friendly Perspective: A Case Study of Xicheng Community in Zhuhai. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2021, 5, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Yao, X.; Dang, A. Confirmation Study on Child Friendliness of Boston Neighborhood from the Perspective of Healthy City. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Tan, J.; Liao, Q.; Yuan, Y. Research on Strategies for Building Healthy Communities Based on Child-friendly Perspectives. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2021, 1, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Wu, X. Strategic Suggestions on the Healthy City Development in the Perspective of Child-friendly City. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2017, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, F. Problems and Countermeasures of Urban Children’s Public Play Space in China: An Analysis Based on the Framework of Child Friendly Community Construction. Contemp. Youth Res. 2022, 3, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Liu, L.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X. The Practice and Exploration of Planning Standards and Guidelines for Childrens Playgrounds: Take London and Shenzhen as Examples. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, P.; Xi, X.; Cai, L. A Comparative Study of Children’s Safe Travel Routes in Tianjin’s Old Residential Areas Based on the Concept of Child-friendly City. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2020, 3, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Huang, B.; Su, J.; Zhang, H. Safety Street Design Strategies for Child-friendly Environment: An Empirical Study of Residential Community in Beijing Old City. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2020, 3, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Gan, L.; Zhu, J. The Implement Paths of International Child-Friendly Cities and Their Enlightenment to Beijing. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Wu, X.; Wei, Y. The Practical Direction of Child-Friendly City Construction: Inspiration from International Experience. Child. Study 2023, 3, 79–87+103. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, P.; Cai, L. Safe Block and Children’s Travel Route (Kindlint) Planning under the Concept of Child-Friendly City: A Case Study of Holland. City Plan. Rev. 2018, 42, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Wei, H. Planning and Design of Children-friendly Outdoor Activity Space in Residential Area. Huazhong Archit. 2022, 40, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Zhu, X. Child-Friendly Street Design with a Focus on Children’s Health. Urban Transp. China 2022, 20, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, J. A Research of Improving Child Friendliness of the Community through Walking School Bus. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 40, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Chang, J. Research on Shanghai Heritage Community Construction and Public Participation Mechanism under the Background of Urban Governance and Spatial Transition. Mod. Urban Res. 2023, 1, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Hua, C. Research on the Mechanism of Children to Induce Community Communication and Promote Community Autonomy. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, C. Research on Micro-renewal Strategy of Old Community from the Child-friendly Perspective. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2021, 7, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Liu, L.Y. Practice of Participation Construction in Shanghai Community Gardens from Child-friendly Perspective. Landsc. Des. 2022, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Kou, H. Study on the Strategy of Micro-renewal and Micro-governance by Public Participatory of Shanghai Community Garden. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 35, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Towards a Welfare-Sharing Society: The Construction Logic and Sustainable Production Mechanism of Child-Friendly Communities—Based on the Practical Experience Research in Shanghai. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2022, 2, 54–65+126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Yan, C.; Dong, X. An Empirical Study on the Influence of Child-Friendliness in Community Public Space on Residents’ Participation in Community Governance. Soc. Sci. Shenzhen 2021, 4, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Tu, S. Land Use Transitions: Progress, Challenges and Prospects. Land 2021, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Paper on the Construction of a Child-Friendly City in Changsha (Release).pdf. Available online: https://etyh.hnup.com/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=/file/%E9%95%BF%E6%B2%99%E5%B8%82%E5%84%BF%E7%AB%A5%E5%8F%8B%E5%A5%BD%E5%9E%8B%E5%9F%8E%E5%B8%82%E5%BB%BA%E8%AE%BE%E7%99%BD%E7%9A%AE%E4%B9%A6(%E5%8F%91%E5%B8%83%E7%A8%BF).pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, L. Child Friendly Planning Practice towards Communicative Action, Changsha. Planners 2019, 35, 77–81+87. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, K. Children’s Rights and the Crisis of Rapid Urbanisation: Exploring the United Nations Post 2015 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Potential Role for UNICEF’s Child Friendly Cities Initiative. Int. J. Child. Rights 2015, 23, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitzman, C.; Nethercote, M.; Mizrachi, D. The Journey and the Destination Matter: Child-Friendly Cities and Children’s Right to the City. Built Environ. 2010, 36, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V. Integrating Community Engagement and Children’s Voices into Design and Planning Education. CoDesign 2015, 11, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Rukus, J. Planners’ Role in Creating Family-Friendly Communities: Action, Participation and Resistance. J. Urban Aff. 2013, 35, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L. Exploring Local Planning Practices in the Context of “Child-Friendly City”—A Case Study of Changsha City. China Conf. 2017, 970–975. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child Text|UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Derr, V.; Kovács, I. How Participatory Processes Impact Children and Contribute to Planning: A Case Study of Neighborhood Design from Boulder, Colorado, USA. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 10, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism To Citizenship. Innocenti Essays 1992, 4, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.; He, X. Exploring the Creation of Community Garden Micro-Renewal Based on Children’s Participation: A Case Study of Beijing N Community. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2021, 6, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade, B.A.; de Sena, Í.S.; Moura, A.C.M. Tirolcraft: The Quest of Children to Playing the Role of Planners at a Heritage Protected Town. In Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection; Ioannides, M., Fink, E., Moropoulou, A., Hagedorn-Saupe, M., Fresa, A., Liestøl, G., Rajcic, V., Grussenmeyer, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 825–835. [Google Scholar]

- Balnaves, K. World Building for Children’s Global Participation in Minecraft. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Sophia Antipolis, France, 23 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Horelli, L. A Methodological Approach to Children’s Participation in Urban Planning. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranker | WOS Journal Name | NP | CNKI Journal Name | NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 23 | Beijing Planning Review | 21 |

| 2 | Children’s Geographies | 13 | Chinese & Overseas Architecture | 21 |

| 3 | BMC Public Health | 5 | Urbanism and Architecture | 17 |

| 4 | Children and Youth Services Review | 5 | Shanghai Urban Planning Review | 17 |

| 5 | Urban Forestry & Urban Greening | 5 | Architecture & Culture | 14 |

| 6 | Sustainability | 5 | Human Settlements | 11 |

| 7 | Journal of Transport Geography | 4 | Urban Development Studies | 10 |

| 8 | BMJ Open | 4 | Contemporary Horticulture | 10 |

| 9 | Cities | 4 | Urban Planning International | 9 |

| 10 | Child Abuse & Neglect | 4 | Design Community | 8 |

| Ranker | WOS Researchers | NP | Ranker | CNKI Researchers | NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smith, Melody | 5 | 1 | Shen, Yao | 16 |

| 2 | Couto De Oliveira, Maria Ines | 4 | 2 | Liu, Lianlian | 7 |

| 3 | Venancio, Sonia Isoyama | 4 | 3 | Lie, Lei | 7 |

| 4 | Witten, Karen | 4 | 4 | Lin, Ying | 6 |

| 5 | Buccini, Gabriela | 3 | 5 | Liu, Sai | 5 |

| 6 | Carroll, Penelope | 3 | 6 | Zong, Lina | 5 |

| 7 | Egli, Victoria | 3 | 7 | Lei, Yuechang | 5 |

| 8 | Said, Ismail | 3 | 8 | Yu, Yifan | 5 |

| 9 | Bertoldo, Juracy | 2 | 9 | Deng, Lingyun | 5 |

| 10 | Perez-Escamilla, Rafael | 2 | 10 | Qiu, Hong | 4 |

| Ranker | Key Words | Degree | Betweenness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Child-Friendly Cities | 25 | 164.437 |

| 2 | Children | 24 | 135.444 |

| 3 | Urban Planning | 11 | 10.827 |

| 4 | Built Environment | 8 | 11.007 |

| 5 | Participation | 4 | 0 |

| 6 | Children’s Participation | 5 | 1.75 |

| 7 | Independent Mobility | 9 | 25.351 |

| 8 | Urban Design | 9 | 25.735 |

| 9 | Child Protection | 3 | 1.033 |

| 10 | Children’s Rights | 4 | 1.987 |

| Ranker | Key Words | Degree | Betweenness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Child-friendly | 145 | 77.994 |

| 2 | Child-friendly city | 97 | 54.077 |

| 3 | Children | 61 | 60.469 |

| 4 | Public space | 61 | 14.167 |

| 5 | Child participation | 42 | 8.504 |

| 6 | Child-friendly community | 24 | 8.575 |

| 7 | Residential area | 27 | 4.483 |

| 8 | Landscape design | 23 | 3.468 |

| 9 | Community | 27 | 2.383 |

| 10 | Design strategy | 15 | 14.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, Y.; Furuya, K. A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12101919

Liao Y, Furuya K. A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022. Land. 2023; 12(10):1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12101919

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Yuhui, and Katsunori Furuya. 2023. "A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022" Land 12, no. 10: 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12101919