Transition Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in Suburban Villages of Megacities under Policy Intervention: A Case Study of Dayu Village in Shanghai, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transition Characteristics

2.2. Land Policy Mechanism

2.3. Research Framework

3. Methodology

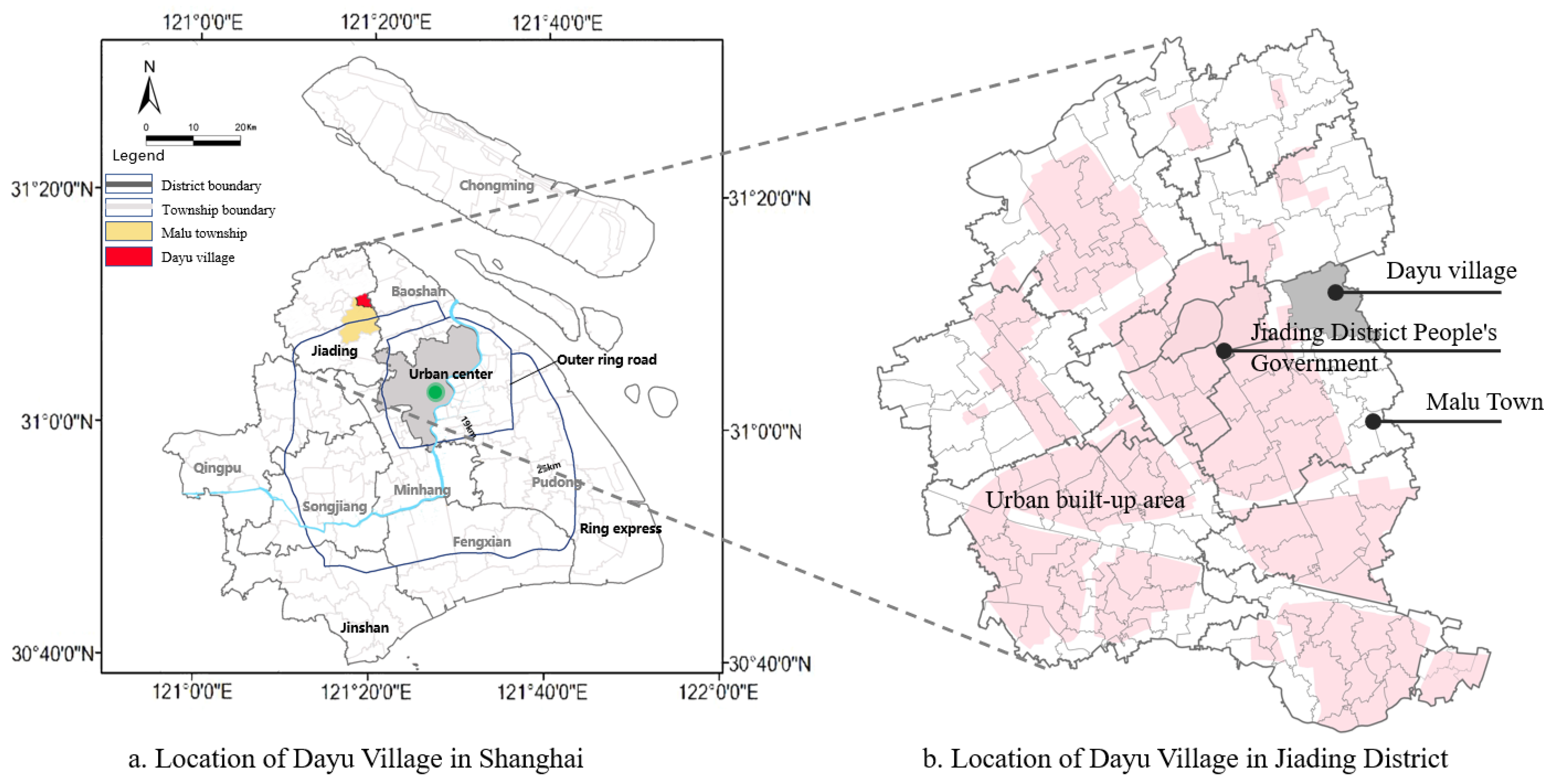

3.1. The Selection and Overview of the Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Participatory Rural Appraisal

3.2.2. Questionnaires and Data Processing

3.2.3. In-Depth Interviewing

3.3. Research Method

4. Results

4.1. Rural Development Stage

4.1.1. Strict Homestead Control Stage (before 2000)

“Grape cultivation in our village began in 1981. The village had many rivers at that time, and the planting conditions were good. The villagers also set aside a piece of land to grow grapes when growing grain. At that time, there were few migrant workers, people with the same surname lived together, and the houses were adequate, so the village changed very slowly.”(VC1)

4.1.2. Village Relocation Stage (2000–2010)

4.1.3. Land Consolidation Stage (2010–2020)

“In 2010, we planned to add land for tourist facilities, but the Jiading District Planning Bureau told us that we can only add land for tourism construction after reclaiming the original industrial land.”(VC2)

4.2. Characteristics of the Land Use Transition

4.2.1. The Spatial Differentiation of the Land

4.2.2. An Orderly Form of Spatial Layout

4.2.3. The Diversity Transition of Village Houses

4.3. The Transition Characteristics of Economic Space

4.3.1. Complex, Multifunctional Industrial Structure

“The quality of the grapes in Dayu Village is good. Although the price of grapes purchased in downtown Shanghai is lower, they are not fresh, and the taste is not good.”(T1)

“I used to come in the summer and just buy the grapes. Nowadays, I sometimes take my children to participate in some outdoor parent-child activities or take relatives to visit the village.”(T2)

“Nowadays, there are many migrant workers, making social security more difficult. Therefore, we have established both daytime and nighttime defense teams, which increases the administrative expenditures.”(VC2)

4.3.2. Diversification of Villagers’ Livelihoods

“I used to work in downtown Shanghai, where the salary was not high, and the rent was expensive. Now I’m back in the village, the house is spacious. I also run a farm business, which gives me some savings.”(V3)

“There are two houses which were left to me by my grandfather. One house has six rooms for rent, and the monthly rent for two houses can be 7000 RMB.”(V5)

“I work for a tourism company in the village, doing some tourism reception and service work. I also have a house for rent. In total, I can get 8400 RMB a month.”(V4)

“If the village needs labor to develop industry, I am willing to participate in it.”(V2)

“I am willing to spend part of my money to invest in the village collective to support the further development of tourism.”(V1)

4.4. Transition Characteristics of Social Space

4.4.1. Demographic Alienation

“I come from Jiangsu Province and work in Malu industrial zone. I live here because the house rent is cheap.”(M2)

“My hometown is Anhui Province, and I’m an online ride-hailing driver. The housing in the village is cheap, the parking lot and charging stations are also available. So I decide to live here.”(M3)

4.4.2. The Defamiliarization of Social Relations

“I come here with my wife, and our children are in high school in my hometown.”(M1)

“I only met the landlord when I signed the rental contract. I usually transfer money through WeChat.”(M4)

“All the tenants share the kitchen, but the tableware is separated. I usually contact acquaintances in my hometown, and seldom with contact other co-tenants.”(M5)

5. Discussion of Policy Mechanisms

5.1. Policies Regulate the Needs of Villagers and Trigger Spatial Changes

5.2. Gradual Policy Improvement Forms External Power

5.3. Differentiated Behavioral Responses Form Internal Dynamics

5.4. Policy Recommendations

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Findings

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gavari-Starkie, E.; Espinosa-Gutiérrez, P.-T.; Lucini-Baquero, C. Sustainability through STEM and STEAM Education Creating Links with the Land for the Improvement of the Rural World. Land 2022, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, F.; Loopmans, M.; Strijker, D.; Haartsen, T. Guest editorial: Changing villages; what about people? J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Liang, X. Expanded Residential Lands and Reduced Populations in China, 2000–2020: Patch-Scale Observations of Rural Settlements. Land 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, J.; Wang, S. How Urban Expansion Triggers Spatio-Temporal Differentiation of Systemic Risk in Suburban Rural Areas: A Case Study of Tianjin, China. Land 2022, 11, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Rural Sociology Revival: Engagements, Enactments and Affectments for Uncertain Times. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 60, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of urban-rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Qiao, W.; Hu, Y.; He, T.; Jia, K.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y. Land-Use Transition of Tourist Villages in the Metropolitan Suburbs and Its Driving Forces: A Case Study of She Village in Nanjing City, China. Land 2021, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Geng, H.; Yue, L.; Li, K.; Huang, L. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Rural Settlements Transformation in the Metropolis: A Case Study of Pudong District, Shanghai. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 755207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, M.; Lurie, S. If Your Rural Community Is Failing, Just Leave? The Revival of Place Prosperity in Rural Development Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 0739456X19895319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.; Nielsen, T.S.; Aalbers, C.; Bell, S.; Boitier, B.; Chery, J.P.; Fertner, C.; Groschowski, M.; Haase, D.; Loibl, W. Strategies for sustainable urban development and urban-rural linkages. Eur. J. Spat. Dev. 2014, 2014, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Guo, T. Measurement of Urban–Rural Integration Level in Suburbs and Exurbs of Big Cities Based on Land-Use Change in Inland China: Chengdu. Land 2021, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.F. Environmentalism in periods of rapid societal transformation: The legacy of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom and the Meiji Restoration in Japan. Sustain. Dev. 1999, 7, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-J. Implications of Korea’s Saemaul Undong for international development policy: A structural perspective. Korean J. Policy Stud. 2010, 25, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, F.; Marchand, G.; Negrão, M. Local history and landscape dynamics: A comparative study in rural Brazil and rural France. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Qiao, W.; Chai, Y.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y.; Ge, D. Spatial distribution characteristics of rural settlements under diversified rural production functions: A case of Taizhou, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 102, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Tian, Y.; Shang, R.; Wei, S.; Li, Y. Urban-Rural construction land Transition(URCLT) in Shandong Province of China: Features measurement and mechanism exploration. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, R.; Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Cividino, S.; Salvati, L.; Quaranta, G. From Rural Spaces to Peri-Urban Districts: Metropolitan Growth, Sparse Settlements and Demographic Dynamics in a Mediterranean Region. Land 2020, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Weng, D.; Liu, H. Decoding Rural Space Reconstruction Using an Actor-Network Methodological Approach: A Case Study from the Yangtze River Delta, China. Land 2021, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Li, W.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, R. Multifunctionality assessment of the land use system in rural residential areas: Confronting land use supply with rural sustainability demand. J. Env. Manag. 2019, 231, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Li, H. Spatial pattern evolution of rural settlements from 1961 to 2030 in Tongzhou District, China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Ye, C. The Integration of New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization Strategies in China: Origin, Reality and Future Trends. Land 2021, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsa, M.; Mupepi, O.; Musasa, T. Spatio-temporal analysis of urban area expansion in Zimbabwe between 1990 and 2020: The case of Gweru city. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, F.; Ke, X. Rural industrial restructuring in China’s metropolitan suburbs: Evidence from the land use transition of rural enterprises in suburban Beijing. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egidi, G.; Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Cividino, S.; Quaranta, G.; Salvati, L.; Colantoni, A. Rural in Town: Traditional Agriculture, Population Trends, and Long-Term Urban Expansion in Metropolitan Rome. Land 2020, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Pulpón, Á.R.; Cañizares Ruiz, M.d.C. Enhancing the Territorial Heritage of Declining Rural Areas in Spain: Towards Integrating Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches. Land 2020, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foelske, L.; van Riper, C.J.; Stewart, W.; Ando, A.; Gobster, P.; Hunt, L. Assessing preferences for growth on the rural-urban fringe using a stated choice analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Loopmans, M. Land dispossession, rural gentrification and displacement: Blurring the rural-urban boundary in Chengdu, China. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, C. Household Registration, Land Property Rights, and Differences in Migrants’ Settlement Intentions—A Regression Analysis in the Pearl River Delta. Land 2021, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, L. Village classification in metropolitan suburbs from the perspective of urban-rural integration and improvement strategies: A case study of Wuhan, central China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Pawson, H.; Han, H.; Li, B. How can spatial planning influence housing market dynamics in a pro-growth planning regime? A case study of Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.O.; Govindan, K.; Boggia, A.; Loisi, R.V.; De Boni, A.; Roma, R. Local Action Groups and Rural Sustainable Development. A spatial multiple criteria approach for efficient territorial planning. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Rudloff, M.; Abdullaev, I.; Thiel, M.; Löw, F.; Lamers, J.P.A. Measuring rural settlement expansion in Uzbekistan using remote sensing to support spatial planning. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Rural geography: Globalizing the countryside. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 32, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaller, W. Die zentralen Orte in Suddeutschland: Eine okonomisch-geographische Untersuchung uber die Gesetzmassigkeit der Verbreitung und Entwicklung der Siedlungen mit stadtischen Funktionen. Jena 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Pacione, M. Rural Geography; Harper and Row: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, G.; White, S.D. Changes in service provision in rural areas. Part 1: The use of GIS in analysing accessibility to services in rural deprivation research. J. Rural Stud. 1997, 13, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.J. New emphases for applied rural geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1980, 4, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, G.; Jiang, C.; Bai, J. Differentiation of spatial morphology of rural settlements from an ethnic cultural perspective on the Northeast Tibetan Plateau, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, M. Spatial and temporal change in urban-rural land use transformation at village scale—A case study of Xuanhua district, North China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural recovery or rural spatial justice? Responding to multiple crises for the British countryside. Geogr. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Smith, D.; Brooking, H.; Duer, M. The gentrification of a post-industrial English rural village: Querying urban planetary perspectives. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromentin, J. A spatio-temporal approach to population diversity: Immigration and rural areas in France. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 103, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Sustainable Geographical Changes in Rural Areas: Key Paths, Orientations and Limits. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.A.d.P.; dos Santos, V.J.; Alves, S.d.C.; Amaral e Silva, A.; da Silva, C.G.; Calijuri, M.L. Contribution of rural settlements to the deforestation dynamics in the Legal Amazon. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Tu, S. Multi-scale analysis of rural housing land transition under China’s rapid urbanization: The case of Bohai Rim. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, W. Expansion of Rural Settlements on High-Quality Arable Land in Tongzhou District in Beijing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Deng, Y.; Tang, Z.; Cao, R.; Chen, Z.; Jia, K. Adaptive capacity of mountainous rural communities under restructuring to geological disasters: The case of Yunnan Province. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Kong, X.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal Decoupling between Population and Construction Land in Urban and Rural Hubei Province. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Evolution and transformation mechanism of the spatial structure of rural settlements from the perspective of long-term economic and social change: A case study of the Sunan region, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Li, Y.; Ma, W. Multi-scale analysis on spatial morphology differentiation and formation mechanism of rural residential land: A case study in Shandong Province, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, Q. Does urbanization always lead to rural hollowing? Assessing the spatio-temporal variations in this relationship at the county level in China 2000–2015. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Wang, D.; Li, W.; Guo, H.; Zheng, Q. Rural settlements transition (RST) in a suburban area of metropolis: Internal structure perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y. Addressing the rural in situ urbanization (RISU) in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region: Spatio-temporal pattern and driving mechanism. Cities 2018, 75, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Fang, L. The Impossible in China’s Homestead Management: Free Access, Marketization and Settlement Containment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Radmehr, R.; Zhang, S.; Rastegari Henneberry, S.; Wei, C. Driving mechanism of concentrated rural resettlement in upland areas of Sichuan Basin: A perspective of marketing hierarchy transformation. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggart, K. Uneven Demand: Depopulation, Repopulation and Housing Pressure. In A Contrived Countryside; Hoggart, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 175–236. [Google Scholar]

- Khasalamwa-Mwandha, S. Local Integration as a Durable Solution? Negotiating Socioeconomic Spaces between Refugees and Host Communities in Rural Northern Uganda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakarnis, G.; Maliene, V.; Dixon-Gough, R.; Malys, N. Decision support framework to rank and prioritise the potential land areas for comprehensive land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tan, R. Patterns of revenue distribution in rural residential land consolidation in contemporary China: The perspective of property rights delineation. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shen, N.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, B. Association between Rural Land Use Transition and Urban–Rural Integration Development: From 2009 to 2018 Based on County-Level Data in Shandong Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Theorizing land use transitions: A human geography perspective. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, A.; Wynberg, R. Multifunctional landscapes in a rural, developing country context: Conflicts and synergies in Tshidzivhe, South Africa. Landsc. Res 2019, 44, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malu Town Government. Statistical Information of Malu Town (2010–2020, in Chinese); Jiading District Statistics Bureau: Shanghai, China, 2020.

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Chen, S.; Ma, L.; Gan, M. The development of multifunctional agriculture in farming regions of China: Convergence or divergence? Land Use Policy 2023, 127, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Sustainable Geographical Changes in Rural Areas—Social, Environmental and Cultural Dimensions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Smith, D.; Brooking, H.; Duer, M. Re-placing displacement in gentrification studies: Temporality and multi-dimensionality in rural gentrification displacement. Geoforum 2021, 118, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subjects | ID | Age | Interview Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Village Chief | VC1, the former village chief | 72 | Information about the history of the village and significant events in the development of the village. Information about the village’s industrial development. The income and expenditure composition of the village. The composition of the village population and governance difficulties. |

| VC2, the current village chief | 55 | ||

| Tourists | T1 | 52 | The reason for visiting and the time taken to visit the village. The main activities undertaken when visiting the village. |

| T2 | 38 | ||

| Villagers | V1 | 66 | Family demographic composition and educational background. Place of work, type of work, income, and expenses. Time spent constructing the homestead area and village house. Reasons for choosing to live in the village. Willingness to participate in village development and methods for doing so. |

| V2 | 53 | ||

| V3 | 45 | ||

| V4 | 42 | ||

| V5 | 35 | ||

| Migrant Workers | M1 | 52 | Information such as family size, household registration, and educational background. Living area and monthly rent, workplace, and salary. Content and types of leisure activities. Relationships with landlords and local villagers. |

| M2 | 42 | ||

| M3 | 47 | ||

| M4 | 28 | ||

| M5 | 34 |

| Metrics | Formulae | Description | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area metrics | Mean patch size | MPS = A/N | Accounts for the average area of rural settlement patches. | ha |

| Standard deviation of patch area | Reflects the degree of difference in the areas of various patches. | unitless | ||

| Shape metrics | Landscape shape index | Characterizes the shape compactness of rural settlement patches; a high value indicates less compactness. | unitless | |

| Fractal dimension index | Reflects the complexity of the patch boundary, thereby reflecting the impact of human activities on the patch boundary; values between 1 and 2 and values closer to 1 indicate lower complexity. | unitless | ||

| Distribution metrics | Patch density | PD = N/A | Describes the density of rural settlement patches. | 1/ha |

| Landscape division index | Reflects the degree of physical connectivity between patches, i.e., the level of aggregation. | unitless | ||

| MPS | SD | LSI | FRAC | PD | DI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2.45 | 2.07 | 10.05 | 1.28 | 2.91 | 0.99 |

| 2020 | 3.28 | 2.6 | 8.12 | 1.18 | 2.18 | 0.91 |

| Change rate | 33.9% | 25.6% | −19.2% | −7.8% | −25.1% | −8.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, K.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Yue, L.; Jiang, X. Transition Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in Suburban Villages of Megacities under Policy Intervention: A Case Study of Dayu Village in Shanghai, China. Land 2023, 12, 1999. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12111999

Li K, Li K, Liu Y, Yue L, Jiang X. Transition Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in Suburban Villages of Megacities under Policy Intervention: A Case Study of Dayu Village in Shanghai, China. Land. 2023; 12(11):1999. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12111999

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Kaiming, Kaishun Li, Yong Liu, Liying Yue, and Xiji Jiang. 2023. "Transition Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in Suburban Villages of Megacities under Policy Intervention: A Case Study of Dayu Village in Shanghai, China" Land 12, no. 11: 1999. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12111999