Social Enterprises and Their Role in Revitalizing Shrinking Cities—A Case Study on Shimizusawa of Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Methodology—Social Enterprises and Their Role in Urban Revitalization

2.1. Definition, Operation and Role of Social Enterprises

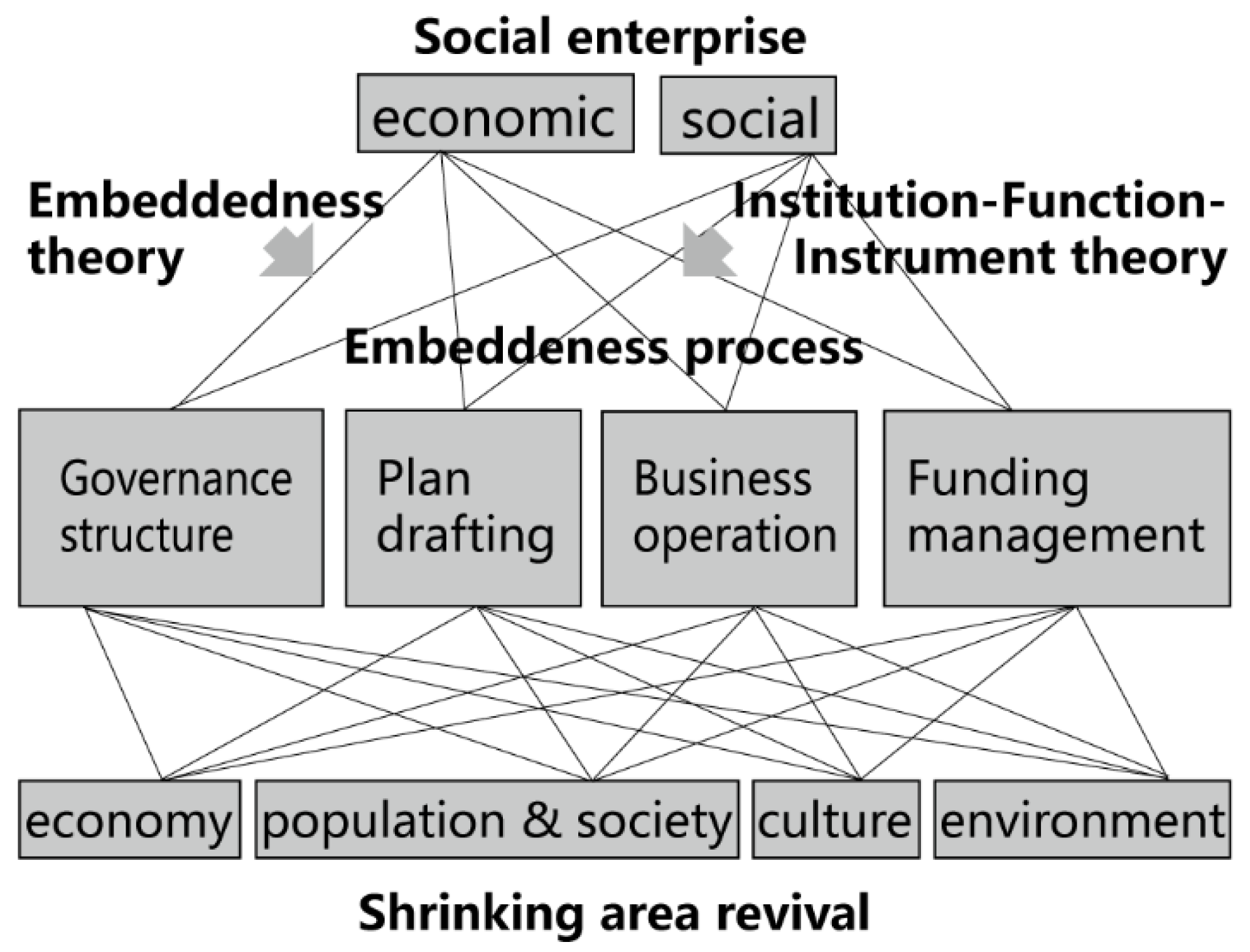

2.2. Analytical Framework of This Study

3. Evidence—Practice of Social Enterprises in Revitalizing Shimizusawa

3.1. Shimizusawa and Its Shrinkage Dilemma

3.2. Characteristics and Mechanism

3.3. Tetrahedron Governance

3.4. Institution Analysis

3.5. Function Analysis

3.6. Instrument Analysis

3.6.1. Planning

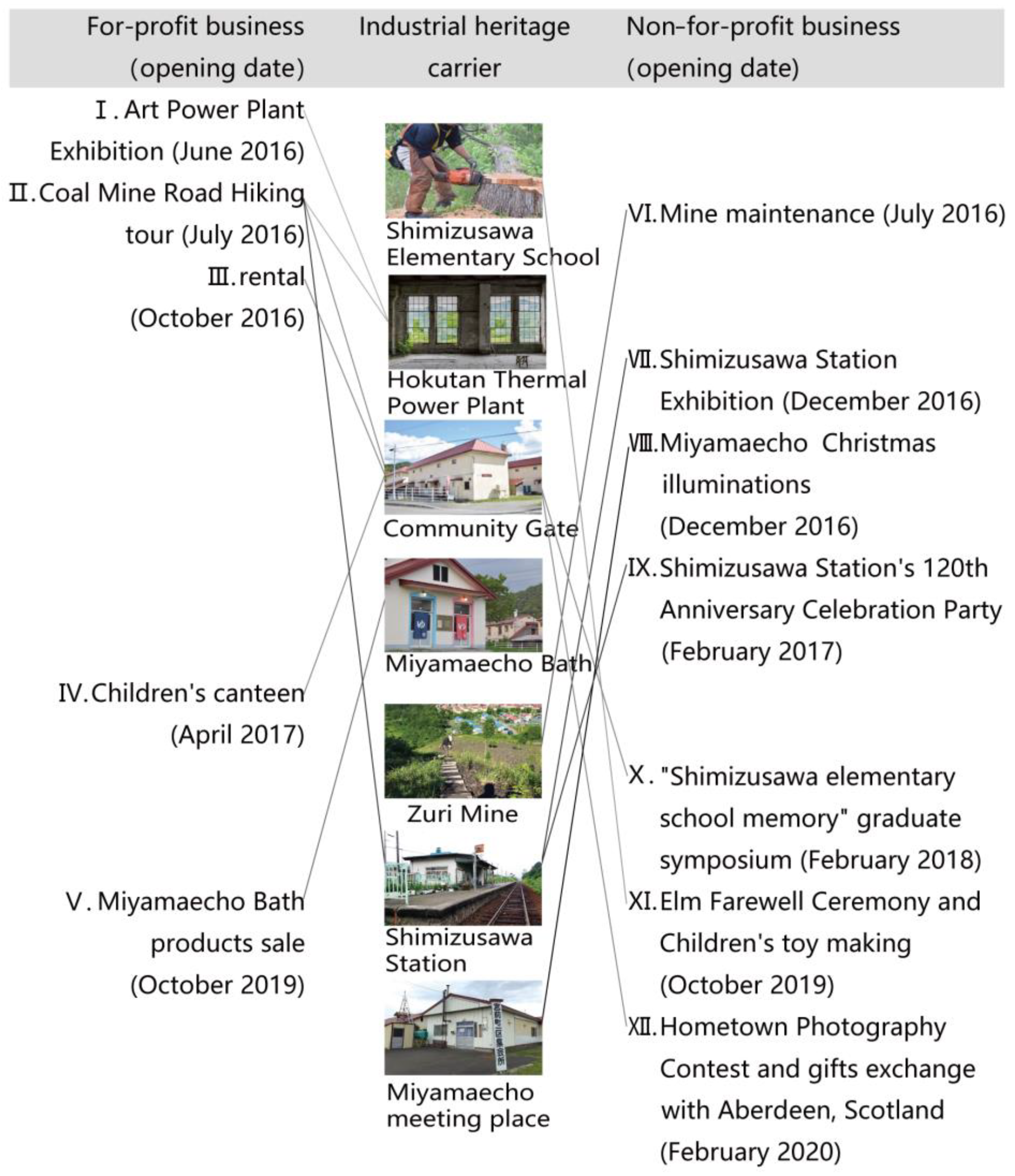

3.6.2. Business Operation

4. Discussions

4.1. The Result of SSE’s Participation in Governance: Obtaining Extensive Supports

4.2. The Role of SSE’s Participation in Governance: Promoting the Multi-Dimensional Revitalization of Shimizusawa Based on Spatial Planning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Häußermann, H.; Siebel, W. Die schrumpfende stadt und die stadtsoziologie. In Soziologische Stadtforschung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1988; pp. 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T. Errors expected-aligning urban strategy with demographic uncertainty in shrinking cities. Int. Plan. Stud. 2008, 13, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. Review of shrinking city research. Urban Plan. J. 2015, 6, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, C.; Wang, W. Analysis and practice of rural vitality under the circumstances of population contraction: Comparative study based on the United States, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. Urban Plan. Int. 2022, 37, 42–49+88. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Jin, Z. Time-space evolution and influencing factors analysis of urban shrinkage in China’s old industrial bases. World Reg. Stud. 2022, 32, 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kiviaho, A.; Toivonen, S. Forces impacting the real estate market environment in shrinking cities: Possible drivers of future development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.H.; Nunes, L.C.; Barreira, A.P.; Panagopoulos, T. What makes people stay in or leave shrinking cities? An empirical study from Portugal. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1684–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, C. Renewal and redevelopment of old industrial areas in the post-industrial period. City Plan. Rev. 2011, 35, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Wang, K. Identification and stage division of urban shrinkage in the three provinces of Northeast China. Acta Geographica Sin. 2021, 76, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Du, L.; Nomura, R.; Yan, S. Rescue the hollowed-out area through industrial heritage tourism: Implications from the practice in Japan’s Sorachi Industrial Area. J. Chin. Ecotourism 2023, 13, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefs, M.; Alves, S.; Zasada, I.; Haase, D. Shrinking cities as retirement cities? Opportunities for shrinking cities as green living environments for older individuals. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Tang, Z. Transformation of traditional British industrial city: The experience of Manchester. Urban Plan. Int. 2013, 28, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G. Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Gert-Jan. Hospers. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glumac, B.; Islam, N. Housing preferences for adaptive re-use of office and industrial buildings: Demand side. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban regeneration between cultural heritage preservation and revitalization: Experiences with a decision support tool in Eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.; Hu, T.S.; Fan, P. Social sustainability of urban regeneration led by industrial land redevelopment in Taiwan. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. A preliminary analysis on the regional identity of Ruhr. Urban Plan. Int. 2007, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. Design strategies to respond to the challenges of shrinking city. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettema, J.; Egberts, L. Designing with maritime heritage: Adaptive re-use of small-scale shipyards in northwest Europe. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Agueda, B. Urban Restructuring in Former Industrial Cities: Urban Planning Strategies. Territ. En Mouv. 2014, 24, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, L. The Shrinking City as a Growth Machine: Detroit’s Reinvention of Growth through Triage, Foundation Work and Talent Attraction. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Wu, Y.J.; Wu, S.M. Development and challenges of social enterprises in Taiwan—From the perspective of community development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chu, S.; Deng, G. Japanese social enterprises under social governance reform: Development, support and challenges. China Nonprofit Rev. 2015, 16, 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, A. An approach to regeneration of old coal mining area by landscape architectural concept and design as a clue for community development in Sorachi region, Hokkaido. J. City Inst. Jpn. 2009, 44, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Persaud, A.; Bayon, M.C. A review and analysis of the thematic structure of social entrepreneurship research: 1990–2018. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2019, 17, 495–528. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gan, T.; Guo, D.; Wang, S. From project management to public management: Review and prospects of PPP research. Manag. Mod. 2020, 40, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Defourny, J. (Eds.) The Emergence of Social Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, X. Social Enterprise Thesis. China Nonprofit Rev. 2010, 6, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, E. Marketing in the Social Enterprise Context: Is it Entrepreneurial? Qual. Mark. Res. 2004, 7, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yan, Z. A review of foreign theoretical research on social enterprises. Theor. Mon. 2009, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Powe, N.A. Community enterprises as boundary organizations aiding small town revival: Exploring the potential. Town Plan. Rev. 2019, 90, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, H.; Manabe, R.; Murayama, A. Regeneration of existing urban areas through small-scale projects by multiple social enterprises: Case analysis of the Central East Tokyo (CET) project set around Kanda Bakurocho Station. J. Urban Plan. 2019, 54, 607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, H.; Manabe, R.; Murayama, A. Possibilities and challenges for social enterprises aiming to revitalize established urban areas through small-scale real estate business. Case study of the “MAD City” project set around Matsudo Station. Analysis. J. Urban Plan. 2018, 53, 748–755. [Google Scholar]

- Eversole, R.; Barraket, J.; Luke, B. Social enterprises in rural community development. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, S.A.; Steiner, A.; Farmer, J. Processes of community-led social enterprise development: Learning from the rural context. Community Dev. J. 2015, 50, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Ramsey, E.; Bond, D. The role of social entrepreneurs in developing community resilience in remote areas. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2017, 11, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottlewski, L. Building and Strengthening Community at the Margins of Society through Social Enterprise. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.; Park, S.; Kim, M. A study on the community-capacity-building of social enterprises-focused on community initiated social enterprises conducting residential environment improvement projects. J. Urban Des. Inst. Korea 2015, 16, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (2011): “Research Committee Report”. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/local_economy/sbcb/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Mair, J.; Robinson, J.; Hockerts, K. (Eds.) Social entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://jeffreyrobinsonphd.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Social-Entrepreneurship-Palgrave-Macmillan-1.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Japanese Government. Act on Authorization of Public Interest Incorporated Associations and Public Interest Incorporated Foundations (Law No. 48 of 2006). 2006. Available online: https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=418AC0000000048 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. The mechanism of social organizations embedded in community governance from a grounded perspective. J. North. Univ. Natl. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2023, 1, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Tina Dacin, M. The embeddedness of social entrepreneurship: Understanding variation across local communities. In Communities and Organizations; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh, H.M. Changing places: The generative effects of community embeddedness in place. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 542–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Embedded development of social work in China. Soc. Sci. Front. 2011, 2, 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sanchis, P.; Aragón-Amonarriz, C.; Iturrioz-Landart, C. How does the territory impact on entrepreneurial family embeddedness? J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2022, 16, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y. Three-dimensional embeddedness: Community foundations help local social governance. China Nonprofit Rev. 2021, 27, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Lan, Y. Progressive Embedding: Strategic Choice of Social Organizations’ Intervention in Rural Revitalization from the Perspective of Uncertainty—Taking S Foundation as an example. J. Public Adm. 2021, 18, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H.D. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How; Whittlesey House: New York, NY, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Jian, L.; Caige, L. Path Selection for the Reform of Planning Management Agencies and Modernization of Spatial Governance in China. China City Plan. Rev. 2021, 30, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M. A Study of Tourism Based on the Concept of Ecomuseum Utilizing Coal Mine Heritage for Regional Revitalization in Yubari City; Sapporo International University: Sapporo, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizusawa, G.I.A. Shimizusawa Project. 2016. Available online: https://www.shimizusawa.com/corporation (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Hokkaido Sorachi Coal Development Bureau. Sorachi Old Mining Area Revitalization Strategy. Available online: https://www.sorachi.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp/ts/tss/sennryaku.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Shimizusawa, G.I.A. A Project to Work on Town Development Utilizing Coal Mine Heritage in the Shimizusawa District of Yubari City. 2016. Available online: https://www.shimizusawa.com/shimizusawaecomuseum (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Shimizusawa, G.I.A. Former Hokutan Shimizusawa Thermal Power Station. 2011. Available online: https://www.shimizusawa.com/hatsuden (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Shimizusawa, G.I.A. Shimizusawa Community Gate. 2016. Available online: https://www.shimizusawa.com/shimizusawacommunitygate (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- St-Pierre, E. Salvage in Yūbari: Machizukuri Against Decline; Concordia University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, M.; Andrew, C.; Ben, M.; Huang, Y.; Luo, Y. Just Transitions in Japan. 2022. Available online: https://energyvalues.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/ba-just-transition-japan-report-updated.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2023).

| Social Interest Representatives | Business Interest Representative | |

|---|---|---|

| Governance structure as whole | Governments of all levels, social organizations, local residents | Entrepreneurs |

| SSE | Social sages, former government officials, social organizations, local residents | Social sages and entrepreneurs |

| Social Interest Maintenance | Business Interest Maintenance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Goals | Governance structure as a whole | Solve social problems, provide public services, maintain public spaces, retain the population, and cultivate cultural pride | Develop diversified industries and provide jobs |

| SSE | Enhance cultural identity by protecting and utilizing industrial heritage and increase the population through child nurturing and cultural activity organizations | Increase economic income through tourism development, apartment leasing, and product sales, etc. | |

| Responsibilities | Governance structure as whole | Outsource public services, make public policies, and issue space use permits | Market-oriented operation and industrial heritage space use right transfer |

| SSE | Obtain the rights of industrial heritage space use and public service broker | Make profits from cultural activities by using industrial heritage, either independently or cooperatively |

| Business Type | Business Name | Supporters and Forms of Support | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Sector | Private Sector | Social Organization | |||||

| Form | Name | Form | Name | Form | Name | ||

| Profit-making business | I. Art Power Plant Exhibition | ○ | Beitan Company | △; ■ | Beitan Company | ▲ | Foundation |

| II. Coal Mine Road Hiking tour | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | |

| III. Community Gate rental | ◑ | City Hall | ■ | consulting firm | ▲ | Foundation | |

| IV. Children’s canteen | ● | City Hall | ◪ | Sales and design staff | ◪ | Regional development organization | |

| V. Miyamaecho Bath product sale | ● | City Hall | △ | Partner Bath | —— | —— | |

| Not-for-profit business | VI. Mine maintenance | ◑ | Municipal government, town and neighborhood committee | ■ | Beitan Company | ■ | Building Materials Association |

| VII. Shimizusawa Station Exhibition | ◑ | Provincial government, city government, station | —— | —— | ▲ | Heritage Conservancy | |

| VIII. Miyamaecho Christmas illuminations | □ | Town neighborhood committee | —— | —— | —— | —— | |

| IX. Shimizusawa Station’s 120th Anniversary Celebration Party | □ | Station, primary school | ◪; ■ | FOOD | —— | —— | |

| X. ”Shimizusawa elementary school memory” graduate symposium | □ | Station | —— | —— | ▲ | Heritage Conservancy | |

| XI. Elm Farewell Ceremony and Children’s toy making | □ | Mayor | ◪ | Toy company | ▲; ◮ | Foundation, citizens | |

| XII. Hometown Photography Contest and gifts exchange with Aberdeen, Scotland | □ | City Hall | ■ | Visual arts company | ▲ | Partner city | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, J. Social Enterprises and Their Role in Revitalizing Shrinking Cities—A Case Study on Shimizusawa of Japan. Land 2023, 12, 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122146

Liu J, Zhang Y, Mao J. Social Enterprises and Their Role in Revitalizing Shrinking Cities—A Case Study on Shimizusawa of Japan. Land. 2023; 12(12):2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122146

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jian, Yixin Zhang, and Junsong Mao. 2023. "Social Enterprises and Their Role in Revitalizing Shrinking Cities—A Case Study on Shimizusawa of Japan" Land 12, no. 12: 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122146