1. Introduction

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake—the largest magnitude earthquake ever registered—caused a massive lowering and flooding of the agricultural lands next to the Cruces River near to the city of Valdivia in Southern Chile (39° S). The earthquake created a wetland of 5000 hectares, and over time this new territory has been colonized by different species of plants and animals, many of them native to the region. This new “natural” ecosystem covered most traces of the land’s previous use. In 1981, during the Pinochet dictatorship, the Chilean state created the Cruces River Nature Sanctuary to protect the portion of the wetland that extends from San José de la Mariquina to the city of Valdivia.

Due to its tremendous biodiversity, the Cruces River Nature Sanctuary has attracted the interest of biologists and ecologists. Since 1988, the state Corporation for Forestry Development (CONAF) and the Universidad Austral de Chile have maintained a cooperation agreement to study the black-necked swan, the sanctuary’s most iconic inhabitant. However, in 2004, industrial liquids were released into the Cruces River from a cellulose factory owned by the company CELCO—this affected the whole trophic cascade, which in the short term led to a dramatic reduction in the black-necked swan population. In response to this contamination, a powerful socioenvironmental movement emerged to protest against CELCO and its impact on the Cruces River, with thousands of people marching in the streets of Valdivia and Santiago. Thus, an environmental social construction emerged following a discourse about swans, wildlife, wetlands, pristine areas and social contestation.

The first aim of this article was to challenge the interpretation of the Cruces River Nature Sanctuary, or places for nature conservation, as territories without acknowledgment of the historical presence of Indigenous people, and other historical land uses, such as those promoted by colonialism. In other words, that the nature sanctuary is currently taken for granted.

The second aim was to illustrate the specific forms of land change and accumulation and to link the colonial organization of the landscape to contemporary extractive practices. The northern sector of the Cruces River Nature Sanctuary contains the ruins of a Spanish fort. This fort—named the San Luis del Alba Fort or the Cruces Fort—was built in the second half of the 17th century, in the context of the attempt by the Spaniards to recolonize the Mapuche-Huilliche (People of the South) and in response to a Dutch expedition of 1643 that took control of Valdivia. This previous use of the land where the Nature Sanctuary lies has been largely forgotten by Chilean society. There is colonial history that must be brought to light to overcome a lack of knowledge about the places that we inhabit. In the case of Chile, and in other former colonies, it is easier to think about empty land ready to be exploited or conserved, than the historical occupation of different Indigenous cultures and peoples who faced dramatic colonization processes. In geography, the concept of “imposing wilderness” has been used to show how conservation could have a colonial character supported by structural inequalities against the local inhabitants [

1,

2,

3]. Meanwhile, in political ecology, evidence from the Global South, especially from Latin America, shows how extractivism is embedded in colonial patterns of land use that can be traced from current socioenvironmental conflicts to ethno-territorial conflicts in Indigenous peoples’ lands since European expansion [

4,

5]. In this context, it is important to understand how landscape history is the history of colonization of Indigenous lands and livelihoods. In the case of Southern Chile and Northern Patagonia in Argentina, this history is of the Mapuche people, their customary territory and Spanish colonization. The “naturalization of nature” may have contributed to Chilean society’s forgetting of the long history of the Mapuche-Huilliche People and their territories [

6], which could be understood as the coloniality of power, knowledge and being [

7].

This article is organized into the following six sections. In

Section 1, the historical background is presented to show the roots of the current conflict between the Mapuche People and the Chilean and Argentinean state. In

Section 2, the production of nature is discussed to understand how power and territory are historically related.

Section 3 details the methods used in the research.

Section 4 focuses on the encomienda as primitive accumulation, metabolic rift and the production of a colonial nature.

Section 5 discusses how colonial nature was produced in Chile, supported by evidence from forts and ”casas-fuertes“, illustrated through a case study of the San Luis del Alba Fort in the Mariquina Valley. Finally,

Section 6 presents reflections about historical landscapes and extractivism.

2. The Dispute about the Indigenous Mapuche Territory and the Emergence of Wallmapu

According to Mapuche intellectuals and Mapuche and non-Indigenous scholars in Argentina and Chile, and influenced by subaltern and decolonial studies, the history of how the Mapuche territory was transformed must be reinterpreted to illustrate how the dispossession of territory took place [

8]. A new generation of researchers are contesting the way in which archives and historical documents have been taken for granted [

9,

10], incorporating alternative explanations which take into consideration Indigenous voices [

11], local memories [

12], participatory methodologies [

13], and other forms of cultural expression against coloniality, such as poetry and music. It is in this intellectual space that this research is located, with the aim to critically illustrate how landscape transformation took form in the River Cruces Nature Sanctuary. This follows how Spanish chroniclers registered land uses change, how these changes needed to be supported by a fort, and how through fieldwork and using remote sensing it is possible to assess how landscape transformation took place.

The Mapuche people are the largest Indigenous people in Southern Chile and Argentina. According to the Chilean census (2017), the Mapuche number almost 1,800,000, while in Argentina there are approximately 130,000. On both side of the Andes there is an ongoing conflict between Mapuche communities and the nation state regarding the process of territorial dispossession suffered by the Indigenous people since mid-19th century. As in other parts of the world, there is an ongoing debate about the pre-existence of Indigenous societies, how they were affected by the colonization process and how the nation state will recognize Indigenous people’s rights to land and water, political autonomy, and economic development [

14,

15,

16].

Pre-Columbian Mapuche culture formed over hundreds of years in large parts of territory in Southern Chile and Northern Patagonia in Argentina. Archeology research recognizes two major cultural complexes in this part of America, with a distinguished material culture, settlements and economy. The first one is called Pitrén, which existed from the year 400 to 1000 A.C. The second culture complex is called Vergel, from 1000 A.C. to the Spanish contact. Research in archaeology argues that these cultures were developed on both sides of the Andes, and they could have an ecological complementation through watershed corridors and a common culture [

17,

18]. For example, there were similar material cultures, expressed in pottery and tools, but also similar cultural practices, such as pre-Columbian navigation mortuary rituals on both side of the Andes [

19]. Ethno-history also illustrates that after the Spanish colonization there were still strong relationships between Mapuche groups throughout the Andes, with specific ritual journeys, but also economic exchanges, and political–military alliances against the Spanish rule, and later against the nation states of Chile and Argentina [

20,

21].

Before the Spanish colonization, archeological and historical evidence suggests that the Mapuche Indigenous people had a complex society that had developed over centuries in the Central Valley and the area surrounding the coastal range and the Andes. These Mapuche specialized in the use of different kinds of landscapes for production, housing, defense and public rituals, among other things, which constituted a mosaic between productive lands and forest [

22,

23,

24].The pre-Columbian Mapuche people were a riverine society in the territory recognized today as Wallmapu, that lived beside and used rivers, lakes, lagoons, wetlands and the sea [

25,

26].

Therefore, according to evidence from archaeology and ethno-history, but also the oral Indigenous traditions and memory, Southern Chile and Northern Patagonia were the customary territory of the Mapuche people. This was the territory defended by their ancestors against Spanish colonization, and this is the territory dispossessed by the Chilean and Argentinean nation states. In the second half of the 19th century, both nation states moved their southern boundaries and began to invade the Mapuche territory using military forces, and converted the land from communitarian uses to private ownership, a process that continued until the first half of the 20th century [

27]. In 1992, and in the context of the commemoration of 500 years since the Spanish colonization of America, a new wave of Mapuche political movements started to be developed in Chile and Argentina. Through the political articulation of their Mapuche identity, these movements fused together traditional forms of territorial organizations, the global struggle of Indigenous people’s rights, and new forms of collective actions [

28,

29]. For example, there are formal deputies in the Chilean parliament, and indigenous communities and associations that negotiate with the state in both countries. Yet, there are also radical groups which use violence against large private companies, clash against the police and occupy private property. The conflict is not only about land, but also about cultural rescue, culturally pertinent local economic development and the protection of ritual sites, among them volcanoes, lakes and rivers.

This new Mapuche movement calls for the political recognition of their “ancestral lands” that were usurped by nation states. These “ancestral lands” started to be called Wallmapu, which means “the whole lands” [

30,

31]. The acknowledgment of Wallmapu is a critical element for the Mapuche movement, because the idea of Mapuche “country” is challenging how boundaries were defined by national states since the 19th century. In addition, the idea of Wallmapu calls for interrogation of how neoliberal extractivism and conservation were imposed during the military dictatorships and the democratic governments in the past 50 years. Military and democratic governments are accused of replicating the colonial discourses which separate Indigenous people from land, to promote environmental transformation led by extractive industries and large investment companies and ignoring the Mapuche people’s trajectories in their customary lands [

8]. For example, in the case of Southern Chile, the construction of large hydropower dams [

32] and the industrial plantation of hundreds of thousands of hectares of non-native trees such as pine and eucalyptus [

33] have been major issues for the Mapuche claims about the Wallmapu [

34]. At the same time, in Argentina and Chile, the conflict is often concentrated in national parks and nature sanctuaries, which historically denies and disrupts the cultural relationships that the Mapuche people have with forests, lakes and volcanoes [

35,

36].

This article is an effort to decolonize landscapes and to think differently about land history. In this context, this article will contribute a reinterpretation of the long-term history of the River Cruces Nature Sanctuary, showing how the Spanish colonization literally “produced” a “new nature” in Wallmapu, which replaced pre-Columbian landscapes with European agriculture, livestock and military sites. This transformation has been forgotten by current Chilean society, and the declaration of this site as a nature sanctuary has aided in the Indigenous history and the previous use of land being overlooked.

The following sections demonstrate how territory has been socially produced in the context of the capitalist mode of production. This perspective is useful to understand colonization as a territorial material process;

Section 5 applies this perspective to understand how landscape transformation took form in Mapuche lands.

3. The Production of Territories for Extraction

This research is located in critical historical geography, following the argument of the production of nature, informed by Smith [

37], following Marx [

38] and Lefebvre [

39]. In this approach, nature has been socially produced and framed within the socionatural relationship of the capitalist mode of production and with a specific socionatural metabolism. This production is not only physical but also symbolic, as the result of political ecological projects, which make and remake the physical and sociopolitical landscape with characteristics according to the capitalist political economy reproduction [

37,

40,

41,

42,

43].

To understand the historical geography of Southern Chile and how it has taken form in socioenvironmental terms, it is important to review the process of primitive accumulation to understand its early production of nature [

38]. Primitive accumulation refers to the historical and violent divorce of the producer from the means of production, as the pre-existence of considerable masses of capital and labor power in the hands of commodity producers. This process constitutes the starting point of the capitalist mode of production. Following the decolonial conceptualization of Dussel [

44], Quijano [

7], Grüner [

45], Escobar [

46] and Mignolo [

47], among others, this paper agues for the importance of considering the dialect between the development of capitalism in Europe and its “dark side” in the Americas to understand the Chilean colonial process and how capitalism could also be a construction from the peripheries to the center.

At the birth of capitalism, European laborers were separated from all property over the means of production, with a lack of means of subsistence and their incorporation of wage labor. The historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production also occurred in colonial Latin America. Yet, unlike in Europe, the producer was not free, but was rather enslaved or quasi-enslaved in the “encomienda”—a Spanish socioeconomic system to capture labor force, rent and commodities—as a rational part of the global capitalist enterprise. Common properties and non-market social institutions were transformed using force, coercion and the uprooting of communities. It is important to understand that in countries such as Chile, most of the Indigenous population was permanently detached from their soil by the privatization of their land (which persists to this day). These people were captured and localized as a labor force in the “estancias”, gold and silver mines, and towns or “pueblos”, and their lands were “emptied” to implant a new metabolism for profit-making. Scholars such as Bagú [

48], Grüner [

45], Gunder Frank [

49] and Quijano [

7] have argued about social class and race as axes of the primitive accumulation in Latin America, while Federici [

50] argued how women were subjected to a new patriarchal order following the arrival of Spanish colonists in Chile. The discussion about the modes of production in Latin America is still debated (see Marchena et al. [

51] and references therein).

Following this, it is possible to think about the primitive accumulation process as a geographical restructuring. Historically, colonial territories have been created for the purpose of extraction through dispossession, causing severe socioenvironmental damage to the colonized territory. Capitalism constantly demands more environments and people for its reproduction, decoupling the economic sphere of social and natural limits [

52,

53,

54]. The capitalist’s geographic expansion transforms nature into a commodity, privatizing and enclosing the commons, incorporating new spaces into the capitalist reproduction, and materially and culturally dispossessing local communities [

55]. In these terms, colonialism can be understood as a “metabolic rift” [

56] that breaks and replaces existing local socioenvironmental relationships, reorganizing them to seek profit and integrating them into the global economy. Therefore, coloniality is also about socioterritorial transformation, which in turn leads to the complete reorganization of ancestral indigenous lands and societies into a new form of socioeconomic structure according to the global capitalist mode of production [

57].

Hence, the nature, landscapes and territories in Southern Chile took the form of this primitive accumulation process. During the Spanish colonization, thousands of Indigenous people were relocated to work in the “encomiendas” and “estancias”, and the Spaniards established cities, forts and missions to control the Indigenous population and transform nature. In modern Chile, extractivism has taken root in the same places where the primitive accumulation period occurred during colonization.

The following section presents the methods used to understand the historical landscape and transformation of Mapuche lands, drawing from historical archives, fieldwork, interviews and remote sensing.

4. Method

This research is framed in historical geography and political ecology. It draws on primary sources, particularly early Spanish chronicles written by soldiers and priests during the first 50 years of colonization, who were witness to the radical landscape transformation of Southern Chile. The research also uses secondary sources, such as historical books, historical cartography and archaeological and ethnohistorical research to illustrate how landscape transformation took form in colonial times. The quotes presented herein were translated from old Spanish to modern English by the author and were checked by a professional translator and a native English proofreader.

To complement the historical analysis, during 2021 and 2022, fieldwork was conducted at the historical sites of the San Luis del Alba Fort in the Cruces River wetland in Southern Chile. Arial surveys were completed using three unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)—a Mavic Mini 2, a Mavic Pro 2 and a Phantom 4 Multispectral. This forms part of ongoing research seeking to explore how to use UAVs and photogrammetric surveying to study historical landscapes as a complementary technique to historical geography, political ecology and landscape archaeology. The use of UAVs for the study of historical landscapes has been expanded by De Reu et al. [

58], Campana [

59,

60], Orihuela and Molina-Fajardo (2021), Brooke and Clutterbuck [

61], Álvarez et al. [

62] and Rouse and Krummow [

63], among others. The images shown in this article were created using photogrammetry, performed orthophoto processing, vegetal health analysis, and applied the digital terrain model (DTM) and digital surface model (DSM) topographic models elaborated with geospatial data WGS 84 using Agisoft Metashape (educational license).

Additionally, a plant health analysis was performed, which determined plant health by comparing the portions of light captured across different bands (red, green, blue and near-infrared); this is based on the fact that healthy plants tend to reflect more green light than red light, whereas unhealthy plants tend to reflect more red light than green light. Following the literature, the Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index (VARI) ((green − red)/(green + red − blue)) was used, which works with RGB sensors, such as the one used by the DJI Mavic Pro 2. VARI analysis allows the detection of areas of crop stress in a field, which can be used as an indicator of the presence of archaeological and historical sites [

64,

65]. According to Brooke and Clutterbuck [

61], UAV surveys of earthworks anomalies help: (a) to identify cropmarks and vegetation growth as well as the surface presence of masonry, pits and ditches, etc.; (b) to identify parch marks and color contrast in the surface; and (c) to identify shadow marks of banks, ditches and low wall foundations produced by a low sun angle. Additionally, the Phantom 4 Multispectral was used with GNDVI analysis (NIR − green)/(NIR + green) [

66] to have a clearer idea about cropmarks and stressed plants resulting from historical human interventions.

These UAV-based archaeological and historical methods are well established in Europe and North America. Yet, the use of UAVs to study historical sites in Southern Chile is at an early stage. This work is among the first to apply UAVs to study the remains of a Spanish fortress in Mapuche lands.

Ethnographic information was obtained through interviews with Indigenous leaders and inhabitants of the Cruces River area in September 2021 and March 2022. This included a total of 20 interviews, which were transcribed and analyzed with the software Atlas Ti.

5. Producing Colonial Territory: The Encomienda

This section focuses on how it is possible to interpret the process of landscape transformation in Southern Chile not as an isolated story but connected with a political economy at the global scale. While European feudalism was in dissolution, in the Americas, colonial societies were imposed upon peoples and lands. However, the plunder from Spanish colonial rule flowed through a feudal institution revisited: the “encomienda”. The “encomienda” in America can be traced from Castilla, Spain, where the term referred to a territorial entity under the rule of a lord who belonged to one of three military orders: Santiago, Calatrava or Alcantara (the conquerors and governors of Chile also belonged to these military orders). In Spain, the “encomienda” collected the rent from the producer for the lord—transforming peasants into vassals—and was additionally a military location to defend the frontier against the Moors in the context of the Reconquest. The lord had a monopoly of violence and acted in matters such as justice and commerce. Meanwhile, the vassals gave the lord money, livestock and services “with their own bodies”, and the lord gave them protection [

67,

68].

In Chile, during the early colonial era (16th and 17th centuries), the production of territory took place in six ways. The first way was through the “encomienda”, which consisted of hundreds or thousands of Indigenous people working in personal service to a lord, or “encomendero”, granted by the Governor. The second was via land grants or “merced de tierras”, which referred to the privatization of Indigenous lands granted by the council. Yet, during colonization in Chile, people and territory—in the form of “caciques”, “rehues” (a patrilineal political and territorial religious organization) and valleys—were granted to a lord as a single entity [

69]. The third way territory was produced was through the estate or “estancia” with private owners as a model of rural property. The fourth was via the construction of Indigenous towns founded on the pre-existing Indigenous settlements. The fifth way was via cities, which were the administrative centers of the colonization process and ruled by the council. Finally, there were the forts and “casas-fuertes”, which functioned as small urban settlements to provide military support to the work of the encomienda [

70].

According to Baker [

71], the Latin American “encomienda” was neither feudal nor capitalist but worked as a means for the temporary enrichment of Spain via gold and silver. Baker argued that the “encomienda” was a barrier to the formation of both private property and of a mass of free laborers, both of which are considered by Marx as a condition for the emergence of capitalism. Yet, as Luis Vitale [

57] argues, in Latin America, and especially in Chile, the “encomienda”, as a socioeconomic category in motion, was one of the preconditions of capitalism. It was the basis for social class stratification, an internal market linked to the world market through Spain, and the growing accumulation of wealth and the commodification of resources and people via the expropriation of the natives’ lands and their kidnapping as slaves, destroying the previous society and producing territories for extraction. The Chilean owners of “encomiendas”, or “encomenderos”, transitioned from soldiers to farmers to producers, and finally to exporters, transforming themselves into agrarian capitalists [

72]. According to Father De Rosales [

73], war, plunder and the slave trade worked together to enrich the Spanish conquerors. De Rosales also widely discusses the violence of and abuse by the colonial authorities and their betrayal of the political agreements with the Mapuche people. Moreover, Pedro de Oña, in his epic poem, “Arauco Domado” (Tamed Arauco) [

74], dramatically narrates the suffering of the Indigenous people in the “encomienda”. The “encomienda” was the medium through which the Spanish entrepreneurs could recover their investment in the colonial enterprise [

75].

In Chile, the “encomenderos” took control of the people, their land, their settlements and their production. The “encomienda” system was an opportunity to reorganize the labor force [

76], and the Indigenous people were relocated according to the will of the “encomenderos”. The Spaniards identified and listed the pre-existing Indigenous social organizations (“cabí”, “regua” or “rehue”) and their “cacique” or “lonko”. This patrilineal, political, territorial and religious organization was composed of small family organizations called “machullas”, “levo” or “lof” [

77]. Zavala [

78] uses the colonial term “repartimentos” to show how the Spanish conquerors penetrated Mapuche territory and were transformed into “encomenderos”, taking control of land and people. For example, Pedro de Valdivia, the conqueror of Chile, took 50,000 people in 12 leagues, which corresponded to a whole Indigenous province. These people were obligated to work in gold mines near the city of Concepción. After Valdivia’s death at the hands of the Mapuche, his “repartimiento” was transferred to his widow. Furthermore, he gave an “encomienda” of 15,000 Indigenous people near the city of Valdivia to his brother-in-law Diego Nieto de Gaete. Moreover, Jeronimo de Alderete had an “encomienda” of thousands of Indigenous people in Toltén, which after death was transferred to his widow [

77] (p. 133).

The chronicler Jeronimo de Vivar wrote that Pedro de Valdivia distributed the province of Osorno between 60 “encomenderos” [

79] (p. 209). Meanwhile, another chronicler noted the large size of the “repartimentos” in the area of the city of La Imperial (

Table 1), which reached 50 “encomenderos” who, they wrote, “were served by the Indians as if they were princes, enjoying the large gifts of this land” [

77] (p. 133).

An anonymous letter in 1580 to the viceroy of Peru regarding the governor of Chile, Rodrigo de Quiroga, denounced how the governor allocated “encomiendas” based only on his personal interest. In that year, 1000 Indigenous people were allocated to his nephew, 500 to a “mestizo” named Pimentel, 400 to a “mestizo” named Cabeza, 400 to Antonio de la Torre, 500 to Antonio Diez, 600 to another “mestizo”, and 500 to Juan Galvez, among other cases [

80] (p. 470). The sender of the letter expressed annoyance that none of these “encomenderos” took part in the war and opined that they therefore did not deserve to receive these “repartimentos”.

Due to unsafe working conditions of the “encomienda”, coupled with illnesses such as typhus (called “chavalongo” by the Indigenous people) and wars since 1552, there was a lack of Indigenous people to perform work in Chile by the end of the 16th century. In a letter to the viceroy of Peru, M. Calderón asked permission to move hundreds of Indigenous people from Chiloé Island to the gold panning site in the city of La Serena [

81] (p. 202), resulting in the relocation of people over a distance of 1688 km, from a rainy temperate marine climate to a subtropical semiarid one. This caused a massive transformation of the cultural ecology of the Mapuche-Huilliche people. Moreover, a request was made for a massive mobilization of Huarpe Indigenous people from present-day Argentina to Chile [

82].

Determining the real number of Indigenous people in Southern Chile during the colonization process is problematic [

83]. Yet chronicles and historical accounts can be used to arrive at an estimate. In 1571, the judge Eda Venegas was commanded by the Spanish Crown to collect the tribute of the “encomienda” in Chile. His records show that Chiloé hosted 160,000 Indigenous people, while La Imperial, Arauco and Concepción hosted 500,000, 200,000, and 80,000, respectively. Additionally, the chronicler Mariño de Lobera, in his account of the Venegas’ visits to Southern Chile, notes that, less than 20 years after the beginning of the colonization process, the number of Indigenous people had reduced from 500,000 to close to 19,000 in La Imperial and from 200,000 to 12,000 in Valdivia. Moreover, Tellez [

83] estimates that by the end of 16th century 100,000 Indigenous people inhabited the areas surrounding Valdivia. Therefore, it can be estimated that the “encomienda” in Southern Chile encompassed more than a million people, the majority of whom were exterminated through this exploitative system until the population was reduced to just 150,000 people at the end of the 16th century [

25] (p. 158).

In territorial terms, the “encomienda” represented the complete and permanent dispossession of the Indigenous ancestral lands in most of Chile. The transformation of these lands into colonized territories was a consequence of the direct actions of the “encomenderos” and the Catholic Church. Moreover, during the Colonial Era, the “encomienda” exported animal tallow, which was even more important to them than the exportation of gold [

49]. The “encomienda” also performed cattle breeding for meat and wool to supply the internal and external markets. The “encomenderos” capitalized their profit by buying land and mines, and the creole merchants invested in ships and products for import and export. Ports and cities grew via the wealth brought by trade relationships with the external market, showing an important urban/rural contradiction. Therefore, the origins of capitalism in Chile were different than those in Europe but contributed to same global political economy history [

57]. In Chile, the “encomienda” was neither an autarkic feudal place nor an agricultural and handicraft site; on the contrary, it was a hybrid place to produce profit and seek investment for more sources of enrichment and business. Vitale argued that “the “encomendero” was a capitalist entrepreneur who used more brutal exploitation methods than the feudal lord over his servants” [

57] (p. 24). By the end of the 16th century, there was a large territorial property in Chile based on the “encomienda” and land grants selling to Peru into a metropolis-satellite scheme.

With the decrease of the Indigenous population in the “encomiendas”, the capture and sale of “Indians of war” was authorized and promoted at the beginning of the 17th century [

72] (p. 191). The estates acquired labor force through the capture of Indigenous people. This situation led to the uprising of the Indigenous people who were forced to work in the estates or “domésticos” in 1655, in which many “encomiendas” and “estancias” were destroyed. The slavery of Indigenous people continued until 1674, when it was forbidden by the Spanish rulers; however, it continued to be practiced until the end of the colonial era. Therefore, the “encomienda” was in motion, underwent frequent changes during the 17th century, and those who were born in the estates and lived and died there were transformed over time into “inquilinos mestizos” working as a “personal obligatory service” [

69]. Hence, dialectally, the “estancia” contained the “encomienda”. From both places, campaigns were conducted to plunder people and goods from the “rebel” lands.

In these terms, Starosta [

84] argues that, during colonialism in Latin America, there was a historical subsumption of indigenous territories into the global circuits of accumulation, reshaping spaces from sources of cheap raw materials and means of subsistence to sources of ground rent recovery for global industrial capital, establishing domestic conditions for the circulation of capital led by the state. Therefore, the “encomienda” was part of the process of the installation of private property, social classes, race, gender and land transformation. It introduced new hierarchies, breaking the metabolism of the previous indigenous societies. Cabrera Pacheco [

85], following a decolonial approach, invites us to consider that all the processes described in this paper are part of the historical and geographical expansion of primitive accumulation and that subsistence forms of production coexist with capital relations and the resistance of the Indigenous people.

6. The Production of Nature in This Primitive Accumulation in Southern Chile

The previous section illustrates how the “encomienda” system was the major driver of landscape transformation and as a consequence, a new produced “nature” disrupted and replaced the pre-Columbian metabolism. Throughout the Southern Chilean “encomienda”, European crops and animals were introduced in a short period of time. These included wheat, barley, cattle, horses, sheep, goats, poultry, donkeys, mules, oxen, fowl, cats and new dog species [

86]. The treatment of these new crops and animals, and the technology used to produce them, were entirely different from ancient Indigenous traditions, and their introduction led to a radically new diet, drinking habits and way of life. For example, the use of grease for candles allowed the nighttime lighting of houses, and the introduction of the Mediterranean plough enabled farmers to work the land with oxen, which in turn produced more erosion than the ancient means of ploughing. It is important to consider that the special places for cultivation that were created by the colonist were differentiated from those for livestock—given the size of the introduced animals such as horses, cows and pigs—which led to the construction of fences and the emergence of private property. Additionally, intensive timber felling was conducted for the construction of housing, forts, shipbuilding and everyday firewood for the Mediterranean kitchens of the Spaniards. An industry developed for the construction of bricks and tiles because the Spaniards sought to replicate their houses in Spain. Furthermore, the cultivation of olives, vines and apples radically changed the land use (as also occurred in some other colonial territories due to sugar cane production, for example, in the Caribbean). All of this led to environmental changes, a cultural–ecological shift, and a transformation of the natives’ worldview [

87,

88,

89]. Following the Indigenous uprising of 1598, exotic plants and animals (e.g., horses) were introduced elsewhere in ancient Mapuche lands and subsequently formed the basis of their resistance and trade with the Spaniards [

73,

90]. In his book “Cautiverio Feliz” (Happy Captivity), the writer Núñez de Pineda y Bascuñán [

91] (who was captured by a “cacique close” to the Cautin River in the early colonization process) described how cattle, horses, pigs and sheep were introduced into the Mapuche diet and ritual feast activities.

From their “encomiendas”, the Spanish penetrated Indigenous lands to capture their production and enslave their people. The colonists distinguished between two different kinds of Indigenous people to support the accumulation process: the so-called Indians of Peace or “indios de paz” or “indios amigos”, who were enslaved in the encomiendas; and the so-called Indians of War or “indios de guerra”, who were targets of looting and slavery. So-called “campeadas”, meaning horseback attacks against the Indians of War, took place every summer; their origin can be traced to the “cabalgadas” used by the Spaniards during the Reconquest against the Moors [

92] and revisited in the colonization of the Americas [

93]. Because of these violent actions, there was a change in Indigenous land use: previously, the Mapuche people produced crops in “vegas” and flat soil; however, after the introduction of exotic seeds, they also started to produce at higher altitudes. They first cultivated wheat, which they allowed to be taken by the Spanish during their looting as a means of appeasement, and then they grew maize, for their own supply. The introduction of cattle also affected the natives’ lands: for example, sheep were adopted, which contributed to the replacement of llamas as livestock. However, llamas were reserved for rituals and diplomacy [

89,

91]. Finally, Indigenous people carried out raids or “malocas”, on the “encomiendas” to capture goods, animals and people, which also caused significant changes in the Mapuche land, especially regarding livestock and the adoption of production technologies.

Abarzúa et al. [

94,

95] developed a palynological record of Lanalhue Lake and the Purén-Lumaco Valley, both of which lie in Mapuche territory. Their analysis shows that, prior to colonization, production in the territory occurred according to a different socioenvironmental metabolism, being characterized by native forest and the cultivation of maize, quinoa, beans and tarweed. Silva [

96] also shows the carpology of the Mapuche territory, identifying quinoa and maize and fruit such as “peumo”, strawberry, “madi” and “quilo” as the basis of the Indigenous diet. The pre-Columbian agrarian production involved platforms and canals that produced a pre-Columbian agrarian landscape. Palynological and carpological records show that, after 1550, the forest was transformed into grasslands through intentional fires, and there was an intensification of farming and the introduction of exotic trees. After this time, native plants such as “mango” and “teca” disappeared and trees were replaced by plantaginaceae, rumex acetosella and pines.

Based on a content analysis of Spanish chronicles, the following pages present evidence of the production of the new nature of the primitive accumulation in Chile. Since this article is part of a special issue about the archeological and historical landscapes of South America, the following material will present quotes to show in detail how the chroniclers illustrate the changes in land use that colonization brought and how this production was connected to Perú, and from there to Europe.

“(…) last summer (the Indigenous people) began to build their settlements, and each lord of caciques gave the seeds to their Indians, such as maize and wheat, which they have planted to supply and sustain themselves. From now onward there will be a large abundance of food, because each year they perform two sowings. In April and May they collect maize, and then sow wheat. In December wheat is collected, and then maize is sown again”

“In three months’ time, which is mid-summer, more than twelve thousand bushels of wheat and maize (…) will be collected in this city. There are more than eight thousand pigs in this land, and there are as many chickens as there are herbs, and in winter and summer they grow without problems, and everything is eaten in abundance”

“Much wheat and barley are collected, and all the other Spanish grains grow very well. The trees and fruits grow better than in Spain. It is remarkable the amount of fruit that it is produced (…) They are raising very good horses, and there is so much livestock of all kinds, and wool of very good colors to make dyes”

“The wheat and barley are extremely good, abundant, and clean. They do not have rye and oats there because they do not need them. From wheat, they make very white and tasty bread (…) All the fruit, grain and vegetables that we have brought to these parts, for example the fruits such as grapes, melons, figs, peaches, pomegranates, quinces, pears, apples, oranges, lemons, and olives are produced in these lands in large amounts, so much that the trees are overloaded because of the abundance. All of these are taken to Peru by sea, with the same quality as Spanish food. These fruits grow so well in that land it is as if they were native fruits from that land”

“I wanted to talk about the things that have been brought to these Chilean provinces from Spain because there are many and very good melons, and very good cabbage, lettuce, radishes, onions, garlic, carrots, eggplants, parsley, chard, thistles, lentils, chickpeas, broad beans, cress, anise, basil, fennel, rue, mustard and turnips. All of them have grown so much that in the fields there are no other things, and the grass is boundless. All of these grow so well, very similar to where they grow best in Spain, and every other plant that could be brought from Spain will grow as well. There are vines and in no part of the Indias do grapes grow so well: they make a very good wine (…) There are fig trees which have very good fruit, and very good pomegranates. There are oranges, limes, citrus, quinces and apples, and any other trees that are brought from Spain will grow very well (…) There is livestock; many mares (…) There are many cows and sheep and goats and pigs, and they are multiplying so well that they are now abundant”

As shown by these chronicles, the introduction of European species caused a metabolic rift in the socionatural relationships of the Indigenous people. In this way, I am not making an essentialist argument, but rather showing how the indigenous lands were integrated with the global market via the consolidation of the “encomienda”, which on one hand was associated with the dispossession of people and lands, and on the other involved the production of new “nature” for mining, livestock, agricultural production and the military control of the territory. At the end of the early colonial period, the Mapuche people were deeply affected by their enslaved working conditions, conflicts with the Spanish army and disease. Some territories were almost emptied of Mapuche, who moved to the coastal mountain range and the Andes to survive [

100] (p. 25). This population continued to practice agriculture in the old way but incorporated exotic seeds. A large part of the surviving Mapuche population transformed their subsistence system from sedentary farming to transhumance with livestock herds [

25]. Next to the frontier with the Spaniards, the Indigenous people fully concentrated on war as a regular army, whereas further inland, farmers supported the war with goods—for example, in the field of “camellones” in Paicaví District [

101]. Moreover, other territories were revolutionized by the Mapuche uprising (1598–1645, and until 1883 in the Araucania territory), which led to a change in the socioethnic hierarchy. In this event, the Indigenous people took control of the main southern cities, captured their inhabitants (mainly women, children and “mestizos”) and took control of the European crops and animals. In other words, there was an appropriation of the metabolism of the primitive accumulation, which reorganized the frontier between the Spanish and the Indigenous world and opened new markets for the Indigenous production, such as cattle. The Mapuche people were transformed into merchants integrated into the colonial economy, especially after the late 17th century, when they expanded to the pampas on the other side of the Andes [

102,

103,

104].

This section argues that the colonization of Southern Chile was a dramatic process of dispossession through blood and fire. It involved the transformation of people and territory for the extraction of profit as primitive accumulation. Territories were transformed to extract gold and produce cattle and wheat. Indigenous people were forced to stay or move as a commodity at the interest of the “encomendero”. In the first 50 years of the Spanish presence, a new colonial production of nature was implanted in Chile. This created a metabolic rift that changed the Indigenous cultural ecology, the political–territorial organizations and the political economy production and its social relationships. Yet, all these changes were deeply resisted by the Mapuche. Due to colonization, the Mapuche also changed, by organizing, adapting and recreating their political ecology for the purpose of war. Dillehay [

105] mentions how, in response to the war against the Spanish, the labor force started to be reorganized, the male population was widely trained for war, some territories were emptied, and other territories were prepared for food production and refuge. As is shown by the case of Tucapel and Paicavi [

101], a military form of land production was introduced, adopting exotic species of plants and animals and building wood forts for defense.

7. Landscape Transformation in the Mariquina Valley: The San Luis del Alba Fort

The aim of this section is to illustrate an example of the historical process of production of nature in Southern Chile, following the case of the San Luis del Alba Fort (

Figure 1). This section demonstrates how the fort “worked” as a major supporter of landscape transformation over customary Mapuche lands and a necessary mechanism for dispossession and the metabolic rift, which was not only about the material transformation of landscapes for profit, but also about the symbolic landscape through the action of Catholic missions. Simply put, colonial landscape transformation created the historical conditions for designation of sites for extraction until the present.

As established in previous sections, the introduction of the “encomienda” and the construction of settlements deeply affected the Mapuche way of life, destroying their cultural ecologies, which placed water at their core and dramatically impacted their mechanism of power reproduction [

77,

79,

99]. The violent advance of the Spaniards—especially after 1550—installed a raw material circuit based on the “encomienda” or “repartimientos” and the use of “casas-fuertes” and forts to support slave work and dispossession [

106]. In colonial times, the Spaniards built 229 fortresses in Chile [

107] (p. 197).

The Spanish chronist Gongora Marmolejo wrote:

“(Near to Concepción) He thought (Pedro de Valdivia), that because there were too many people in the province, it was necessary to build some house-fort to keep them, and to have soldiers in it, to make the Indians’ uprising more difficult, copying the Romans, when they made themselves Lords in Spain (which because of the castles that they built was called Castile)”

Since pre-Columbian times, the valley of Mariquina (in the Mapudungun language, Mari = ten, Kuga = patrilineal groups) had been occupied by the Indigenous people, and early Spanish chronicles describe a rich agricultural landscape (

Figure 1). This territory was an “ayllarehue”—a large political–territorial Mapuche organization based on several “rehues” (called “provincia" by the Spanish). But it was also a node that connected the coast with the Central Valley, the Andes and the destroyed cities of La Imperial, Villarrica and Valdivia. The famous Madre de Dios gold mine was located near to this point and, before the Indigenous uprising, the colonial trade flowed from the Cruces River to the main Spanish cities in America.

In 1645, the Spaniards began to fortify Valdivia, building the forts of Niebla and Corral and a castle on Mancera Island. In Mariquina, they built the Fort of the Virgin, also named the San Luis del Alba, Cruces, or San Joseph Fort, in 1649 (

Figure 2). There is a lack of information about this fort; however, it is known that it was originally armed with 300 soldiers and was connected to Valdivia by the Cruces River [

108]. The fort was later armed by a cavalry of 80 soldiers [

109] (p. 88). The chronicler Father De Rosales mentioned that there were at least three forts on the Cruces River, the first of them being “Nuestra Señora de la Presentación”, which was flooded during winter and abandoned.

“Seven leagues to the north of the city (Valdivia), at the frontier of the rebel Indians, there is another fort, with a company of infantry over a cliff in the river of Mariquina, where it is possible to travel in ships. Its name is Fort de las Cruzes, because of the many crosses that the soldiers hoisted (…) Even though at the beginning the rebel Indians tried to do as they would, they saw the power of the Spanish and the fortresses that they built. They submitted under their indomitable behavior. Manqueante and the other leaders offered their obedience to the King of Spain, and, in order to subject them and maintain them in obedience, the fort San Joseph of Mariquina was founded”

Figure 3 illustrates how the Cruces Fort was located at the confluence of the Cruces, San José and Ralicura Rivers, which are today part of the Sanctuary of the Cruces River Wetland. This confluence was probably very important for the pre-Columbian Indigenous riverine society, and during the colonization process was part of the “Camino Real” (see

Figure 1), which connected Valdivia and Concepción. Gold extraction and the plundering colonial economy were mobilized through these rivers to Valdivia, and from them to the colonial centers. According to Guarda [

111], three volcanos were visible from the fort: Lanín, Villarrica and Mocho-Choshuenco (today, these cannot be seen from the site of the fort due to the presence of large trees). As shown in

Figure 3, the fort is located at a topographic high beside grazing and agricultural lands.

Given its location between three navigable rivers, the fort at Mariquina acted as a node between different territories and ethnicities: it was the place used by the Spaniards and Mapuche-Huilliche to establish diplomacy celebrating at least two parliaments; but it was also the core of the fluvial trade, after 50 years without a Spanish presence in Southern Chile. The chronicler Father De Rosales says:

“(…) it began to “rain” Indians’ gifts, which because of the security that peace brought, and the interest of the Indians to trade with the Spanish, meant that each day a great number of canoes arrived, loaded with sheep, birds, pigs, and food of every kind of vegetable of the land. With all of these, a great commerce was established”

The fort dramatically altered the power asymmetry in Mariquina and the surrounding lands, especially among the different Indigenous leaders, generating a new frontier between the different Indigenous groups. Therefore, a new territory for looting and slavery was produced [

110] (p. 359). The fort was the core of looting and was used to capture people, animals and grain. Yet, the fort was also the core of the Jesuits’ campaign, with Indigenous children being taken to the fort to be indoctrinated. In the following centuries, the fort supported the missions in the Mariquina and Calle Calle valleys—first those of the Jesuits, then the Franciscans and during the Republic times the Capuchins [

112,

113].

The chronicler Father De Rosales is eloquent about this horrible process of colonial accumulation:

“(…) With this fort, the soldiers of Valdivia went out and through a rasa campaign (…) they terrorized and surprised the enemy (…) They entered into enemy lands with great happiness, taking them away from their lands, capturing their children and women, and taking their houses and field crops. With the spoils taken from the enemy, they captured horses and strengthened their caballeria”

Despite its mentions in Father De Rosales’s chronicle, little is known about the San Luis del Alba Fort, even though it controlled the Mariquina Valley for almost 175 years.

Figure 4 shows the possible location of Cruces Village which, according to Astaburuaga [

114], was located on the embankment of San Luis del Alba Fort.

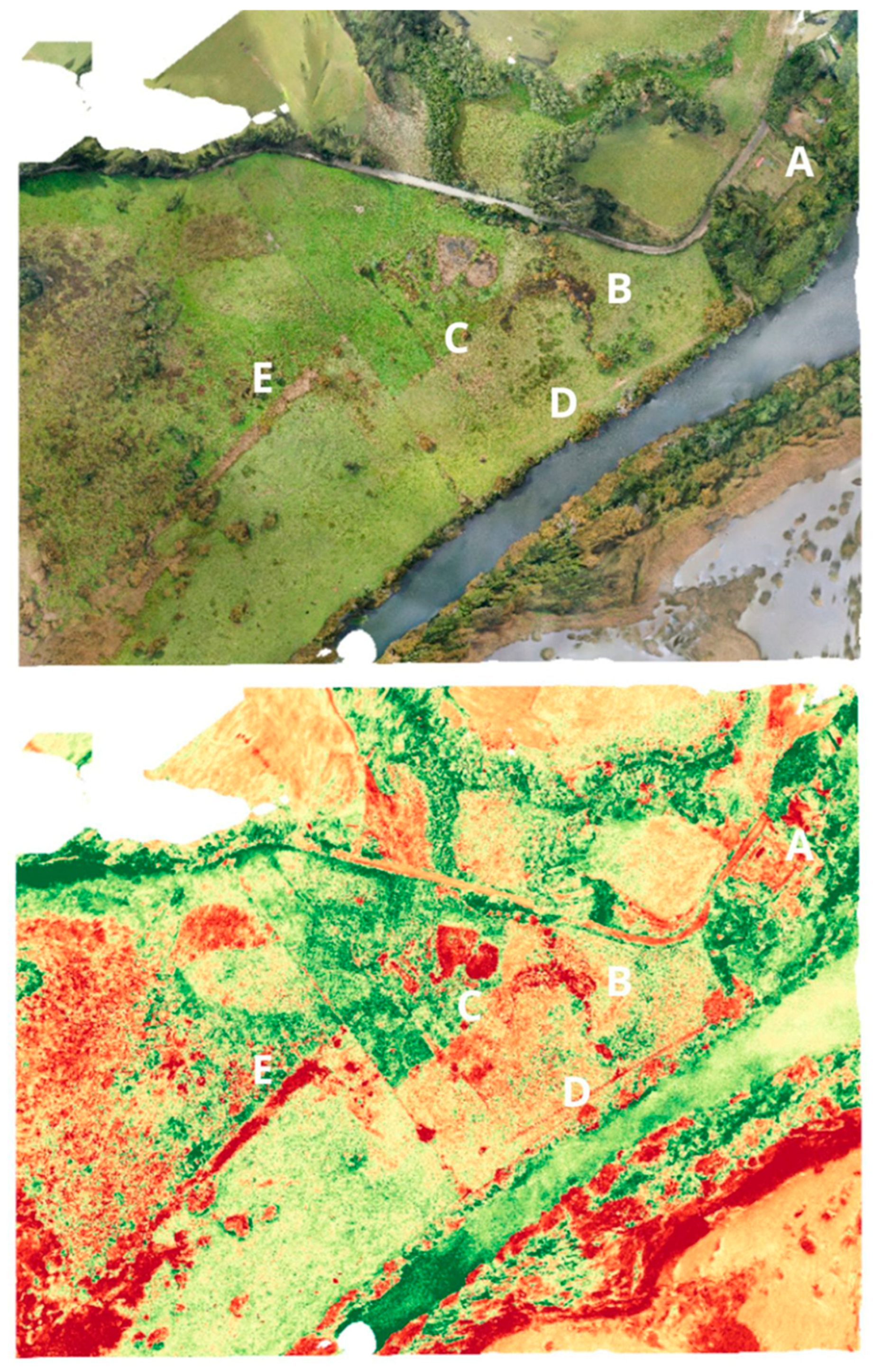

Figure 4 shows the orthophoto and a VARI analysis of this site, based on an image captured using a Mavic Pro 2. VARI analysis helps to identify marks in surfaces, showing stressed plants because of possible earthworks. In this image, A corresponds to the San Luis Fort, B shows a semi-circle, while D could be the remains of a building and has some geometric forms. Letter C shows enclosures and F shows soil interventions which resemble a trench.

This remote sensing analysis is important because the site that will be protected by the local municipality is the one related to the fort’s main building. Yet, in the early 1960s, the archaeological work of Van de Male identified a cemetery near to the embankment, and abundant Hispanic material culture in the fort and surrounding areas. However, as the Anthropological and Archaeological Museum of Universidad Austral de Chile has been closed by the COVID-19 pandemic, access to its archaeological register could not be obtained to know more about the site. During fieldwork from August to October (late winter to early spring) 2021, the locations marked with the letters B, C and D in

Figure 4 were partially under water, and it was impossible to access them to take soil samples. Letter F could be a drainage canal.

As shown in

Figure 4, the use of the VARI index identified structures that could represent enclosures, such as the geometric forms marked by the letters C and D. Therefore, this analysis can contribute to a better understanding of land transformation and allows the analysis of historical sites and their associated landscapes. The next step in this research was to collaborate with archaeologists to survey the northern and southern part of the fort.

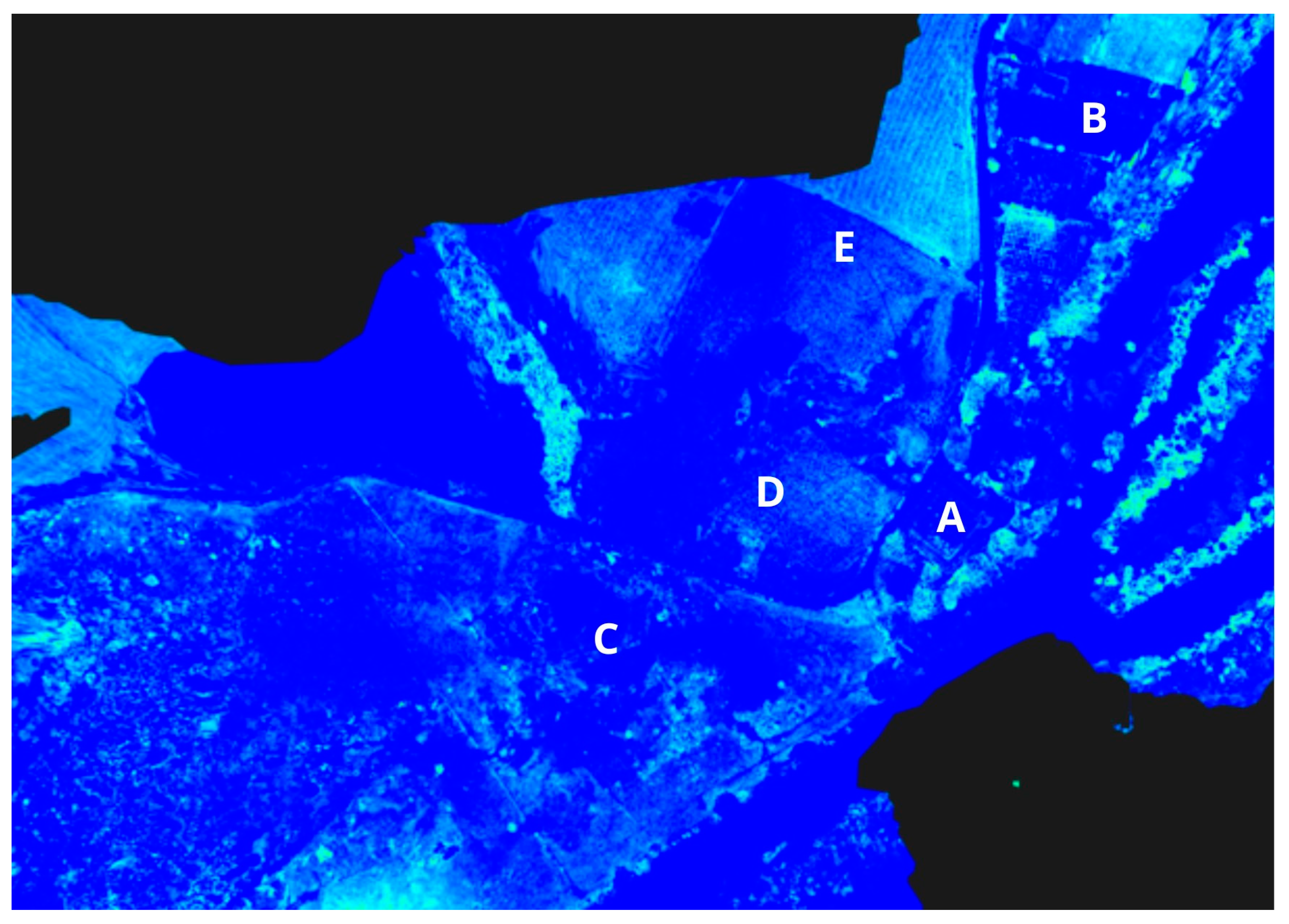

Data from interviews with local inhabitants suggest that the area surrounding the fort was populated in the early 20th century, in the time of their grandparents. Today, this area is a large cattle farm. The landscape elevation model shown in

Figure 5 (obtained using Agisoft Metashape) illustrates possible signs of an urban settlement to the north and south of the San Luis Fort. The northern part of the fort moat seems to continue until it reaches the location of letter C. There is a mound or hill at D which, as suggested during the fieldwork, can be identified as a human intervention due to the existence of some form of steps (see

Figure 6). Thus, this mound may have been part of the fort’s military defenses because it was connected to the fort, although this is a hypothesis.

Taking into consideration letter D of

Figure 5,

Figure 6 shows what seems to be steps in the hill. These may correspond to a defensive site with a palisade to give support to San Luis Fort. Regarding letter D, Father De Rosales [

110] said that there was an Indigenous leader’s residential place in this area, detailed as part of the negotiation process between Mapuche People and Spanish. Father De Rosales established at least two large negotiations between Indigenous and Spanish leaders in the area of the fort. Remote sensing analysis suggests that letter D could be part of this fort complex.

The literature argues that the Luis del Alba de Cruces Fort and the mission of San José formed a social center and the core of an extended agricultural zone [

23]. Moreover, as Father Rosales illustrates in his historical account, the fort was an urban complex with different uses (

Figure 7). From the mid-17th to 19th centuries, Spanish men inhabited Cruces Village, together with their families, the landowners in the “estancias”, whereas the “friends’ captains” [

111], who were mestizos working for the Spanish, probably lived with their families near the village, reaching more than 600 inhabitants in 1655 [

115] (p. 185). Yet, it is also important to think about the “Indians of peace” and the slaves taken in raids, who were forced to work to maintain the production of the valley.

Figure 7 is an NGDVI analysis which possibly shows cropmarks that could correspond to the colonial urbanization, which means a larger space than the one that is recognized by the local municipality and the current archaeological work. In 1740, the Jesuits constructed a large “estancia” in San José to produce cattle, agriculture and forestry for the national market and for export to El Callao and Guayaquil. With the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, this “estancia” was divided into various new “estancias” sold to different private owners. These “estancias” were situated in locations such as Bella Vista, Chorocamayo, El Almuerzo, Aiñaque, Plaza de Armas, Pichoy, Cayumapu, Chihuao and the fluvial islands of Tres Bocas, Culebra and Realejo [

109] (p. 344). In the 18th century, large “estancias” such as El Corcovado and San Ramón were established [

116] (p. 213). The “estancias” represented a way for the Spanish to penetrate into Mapuche-Huilliche lands; they acted as proto-urbanizations of the Cruces riverside, and with the Catholic missions located in the Indigenous reductions, major pressure was exerted on the Indigenous population.

Following the creation of titles for the land and of a land market since 18th century, the Spanish and mestizo populations in the area increased. Today, there is no indigenous community with titles in the San Luis del Alba Fort area, although there are Mapuche-Huilliche families in the process of organization. In 1822, at the very end of the War of Independence, the fort was attacked by Chilean forces, and it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1837 [

109] (p. 263). By 1860, the fort was in ruins, with one observer noting “ruins of an old Spanish fort, with trench rest, drawbridge, some old moldy cannon, over broken gun carriage” [

117] (p. 345). In the early 20th century, Bauer noted that “it was said that there was a fort [beside the Cruces River] in the ancient times” [

118] (p. 38). During interviews, a local resident testified that during the first half of the 20th century, the ruins were occupied by a militia paid by the landowners to prevent Indigenous attacks. In the 1960s, the Universidad Austral de Chile oversaw the reconstruction of the fort, using original Spanish plans, for the purpose of archeological research and heritage protection [

119] (p. 176). The fort is now abandoned and closed to the public.

Cruces Village was abandoned at the end of the 19th century. With the foundation of the city of San José de la Mariquina in 1850, this new urban center attracted people, leading to the concentration of public services such as schools. Hence, rural places, such as Cruces Village, which played a vital role in colonization, lost importance resulting in their disappearance. During the first half of the 20th century, with the colonization of the Mapuche territory commanded by the Chilean state, Indigenous people were relocated to allow the privatization of land and the development of cattle and agriculture. There was a capitalist revolution over the former Mapuche territory, transforming it into the “Chilean wheat bowl” [

120]. Yet, the 1960 Valdivia earthquake deeply affected the productive capacity of Southern Chile: cities, towns, ports, roads and railways were destroyed [

121]. In the Mariquina Valley, the earthquake caused the Cruces River to flood the delta of the river, which was then productive land, creating a large wetland. Therefore, the site of Cruces Village may have been partially covered by water since 1960. For this reason, the use UAVs and remote sensing could contribute to investigate the history of the land.

Today, the land surrounding the San Luis Fort in the middle of River Cruces Nature Sanctuary is a mixture including the Cruces River wetland, cattle “estancias” and industrial eucalyptus and pine plantations. The Mariquina Valley has been specialized for forestry production and is the core of Chile’s cellulose industry (which contaminated the Cruces River in 2004, generating a massive socioenvironmental scandal). The valley’s Indigenous population is currently reorganizing to demand state-funded local development projects.

8. Conclusions

This article shows that the Cruces River Nature Sanctuary, while today seeming entirely natural, has a long social and environmental history associated with the way in which the territory has been produced. Socioenvironmental change is not natural, but is rather a political ecological project, and in Southern Chile, it is a colonial project that is deeply connected with the form that capitalism took in the region. This paper connects three elements of this system: the “encomienda” as a primitive accumulation based on the capture of people and land to produce profit; the metabolic rift produced by colonial territorial relationships; and the emergence of a new nature which, dialectically, destroyed and created the conditions for the Indigenous uprisings and the ongoing Mapuche resistance. Fieldwork, particularly including UAVs and interviews in the San Luis del Alba Fort in the Mariquina Valley, helped illustrate the interlinkages between historical geography and landscape archaeology to make the colonial production of nature visible, and to understand how this Spanish fort supported the production of the new colonial nature and the dispossession and transformation of the Indigenous territories.

In Southern Chile, there is a colonial pattern that constantly produces territories for extraction. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the fort in the Mariquina Valley was the core of such extraction. Since the late 20th century, the CELCO industrial pulp plant has generated an important asymmetry of power in the valley, which has led to socioenvironmental transformation in this region, such as the socioenvironmental scandal after the contamination of the Cruces River. During its history, the landscapes of the Mariquina Valley have been produced and reproduced again and again—from pre-Columbian agriculture, passing to the colonial extraction of gold, cattle, agriculture and forestry, to the large “estancias” which created the agricultural landscapes of Southern Chile, and the present industrial forestry. Neoliberal policies to impose forestry have led to the plantation of thousands of hectares of eucalyptus and pine. From colonization onward, all the land transformations have occurred through the dispossession of Indigenous lands and the marginalization of the Indigenous people.

Finally, it is important to recognize the dramatic suffering of the Mapuche people, how they have historically and systematically resisted these transformations, and how they are currently in a process of organization and conflict. They reject “forestry extractivism” and the “colonial state”, not only through direct action but also by constructing local development plans to overcome their historical structural poverty. They have territorial demands; but they are also demanding political autonomy and cultural development.