Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

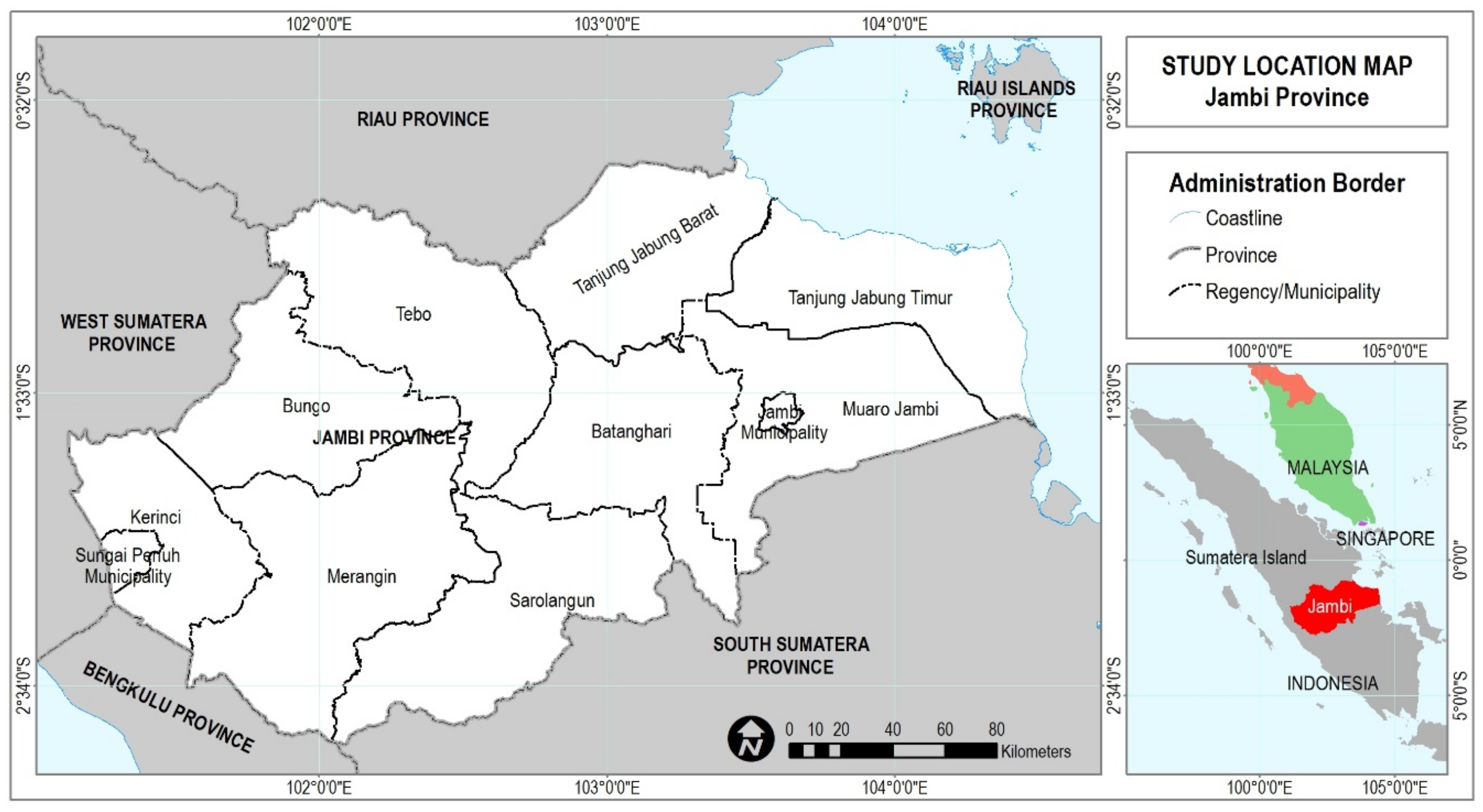

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Preparation

2.3. Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Overview of the Development Progress

3.2. Development Progress at Village Level

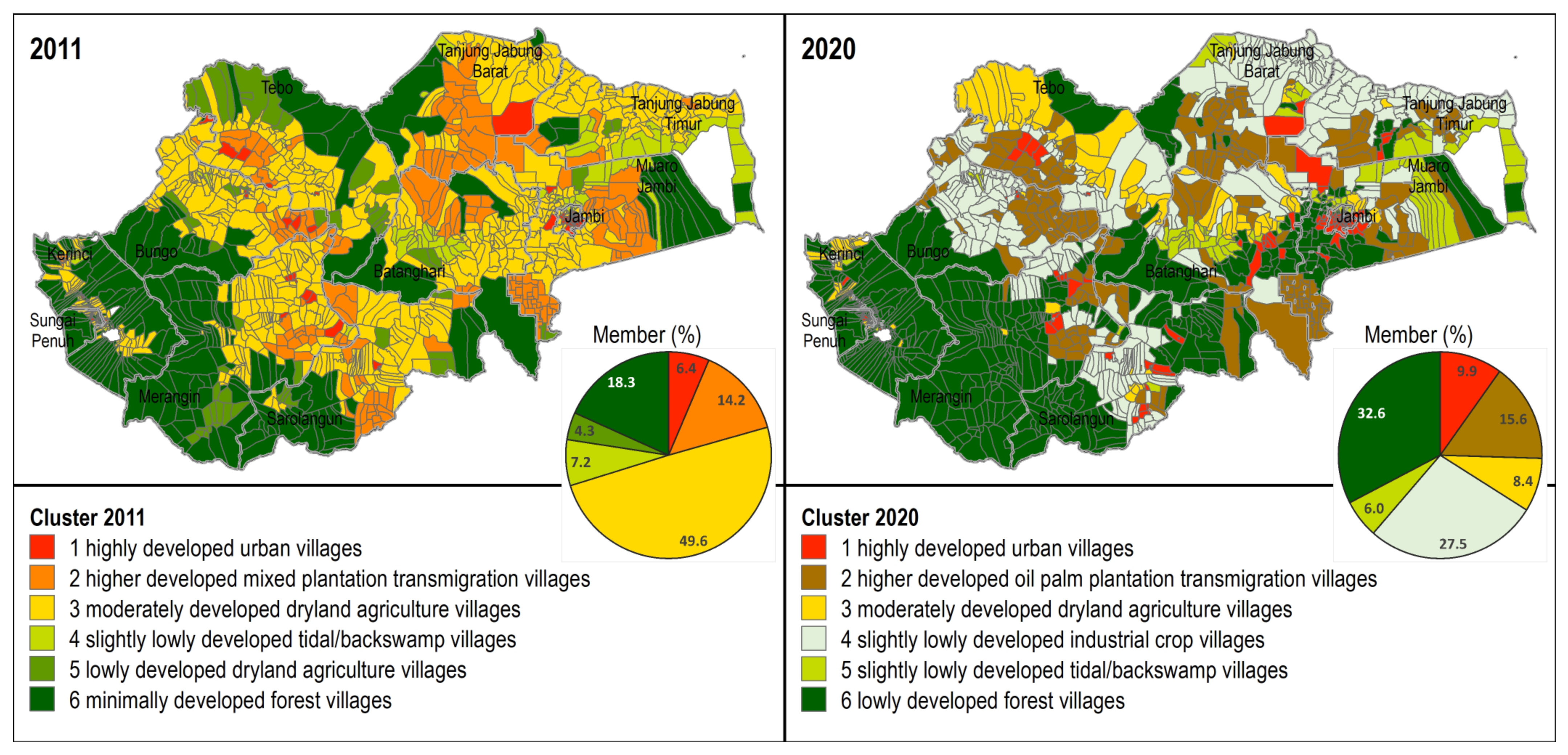

3.3. The Shift in Typology of Rural Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Development Progress at Provincial and Local Levels

4.2. Policies Inducing Development Progress

4.3. The Shift in Village’s Characteristics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chigbu, U.E. Ruralisation: A Tool for Rural Transformation. Dev. Pract. 2015, 25, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Facilitating Inclusive Rural Transformation in the Asian Developing Countries. World Food Policy 2018, 4, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecklov, G.; Menashe-Oren, A. The Demography of Rural Youth in Developing Countries; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.; Brown, D.L. Placing the Rural in Regional Development. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilonoyudho, S.; Rijanta, R.; Keban, Y.T.; Setiawan, B. Urbanization and Regional Imbalances in Indonesia. Indones. J. Geogr. 2017, 49, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrdal, G. The Drift towards Regional Economic Inequalities in a Country. In Economic Theory and Underdeveloped Regions; Duckworth Books: London, UK, 1957; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapa, I.; Sumarmo; Setiawan, B.; Pramoedyo, H. Impact of Rural Area Development in Driving Regional Growth of Bone Bolango Regency: Case Study of “Desa Tumbuh Daerah Maju. Italienisch 2022, 12, 885–892. [Google Scholar]

- Rustiadi, E.; Saefulhakim, S.; Panuju, R.D. Perencanaan Dan Pengembangan Wilayah, 2nd ed.; Pravitasari, A.E., Ed.; Crespent Press & Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Agunggunanto, E.Y.; Arianti, F.; Kushartono, E.W.; Darwanto. Pengembangan Desa Mandiri Melalui Pengelolaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES). J. Din. Ekon. Bisnis 2016, 13, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.J.; Boonstra, W.J.; Peterson, G.D.; Schlüter, M. Traps and Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Review. World Dev. 2018, 101, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravitasari, A.E.; Rustiadi, E.; Singer, J.; Fuadina, L.N. Developing Local Sustainability Index (LSI) at Village Level in Jambi Province. In International Proceeding of the 8th Rural Research and Planning Group International Conference, Yogyakarta, 16–17 May 2017; Suratman, Baiquni, M., Hasanati, S., Eds.; Gadjah Mada University Press: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. Unleashing Rural Development through Productive Employment and Decent Work: Building on 40 Years of ILO Work in Rural Areas. In Proceedings of the ILO Committee on Employment and Social Policy, 310th Session, Geneva, Switzerland, 21 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Desa Pembangunan Daerah Tertinggal dan Transmigrasi. Rencana Strategis Kementerian Desa, Pembangunan Daerah Tertinggal Dan Transmigrasi 2020–2024; Kemendes PDTT: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020.

- Potter, L. New Transmigration ‘Paradigm’ in Indonesia: Examples from Kalimantan. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2012, 53, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi. Transmigration In Jambi Province from the Perspective of Regional Policymakers. Jambura Agribus. J. 2022, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Hardy, D. Addressing Poverty and Inequality in the Rural Economy from a Global Perspective. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 61, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodiyah. Reformation of the Administration of Village Government in Indonesia Based on Law Number 6 of 2014 on Villages (Comparing Normative and Empirical Facts on Villagers Participation). In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Indonesian Legal Studies (ICILS 2018), Semarang, Indonesia, 25 July 2018; Rodiyah, Suhadi, Anitasari, R.F., Muhtada, D., Arifin, R., Eds.; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadah, M.; Sampoerno, M.N.; Triansyah, Z.; Chaniago, F. Pengembangan Pengelolaan Pariwisata Oleh Badan Usaha Milik Desa Di Jambi. KAMBOTI J. Ilmu Sosial. Hum. 2021, 1, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, B.A. Pelaksanaan Otonomi Desa Pasca Undang-Undang Nomor 6 Tahun 2014 Tentang Desa. J. USM Law. Rev. 2019, 2, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vel, J.A.C.; Bedner, A.W. Decentralisation and Village Governance in Indonesia: The Return to the Nagari and the 2014 Village Law. J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 2015, 47, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshari, K. Indonesia’s Village Fiscal Transfers (Dana Desa) Policy: The Effect on Local Authority and Resident Participation. J. Studi Pemerintah 2018, 9, 619–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekasdi. Selayang Pandang Proyek Transmigrasi Jambi; Soekasdi: Jambi, Indonesia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Praja, S.W.; Pratama, M.R.B. Transport Management in Rural Areas to Improve Road Safety User. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1092, p. 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilianti, V.; Harkeni, A.; Andriany, E.; Bahri, Z. Paper Technical Efficiency of Infrastructure Spending Nexus Unemployment of District/Municipalities in Province of Jambi. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Harbin, China, 9–11 July 2021; Ali, A., Linton, A.L., Eds.; IEOM Society: Southfield, MI, USA, 2021; pp. 609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Achmad, E. Analysis of Industrialization and Economic Growth in Jambi Province. In Malaysia Indonesia International Conference on Economics, Management and Accounting (MIICEMA) 2016, Jambi, Indonesia, 24–25 October 2016; Junaidi, Johannes, Yacob, S., Lubis, T.A., Rahayu, S., Eds.; Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Jambi: Jambi, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rustiadi, E.; Mulya, S.P.; Pribadi, D.O.; Saad, A.; Supijatno; Iman, L.O.S.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Ermyanyla, M.; Nurdin, M. Study of Oil Palm Plantation on Peatland under Spatial Policies in Jambi Province, Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1025, p. 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinebach, S. “Today we occupy the plantation—Tomorrow Jakarta”: Indigeneity, land and oil palm plantations in Jambi. In Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia; Hauser-Schäublin, B., Ed.; Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2013; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Suprianto, D.; Effendi, I.; Budiardi, T.; Widanarni; Diatin, I.; Hadiroseyani, Y. Evaluation of Aquaculture Development in the Minapolitan Area of Merangin Regency, Jambi Province, Indonesia. AACL Bioflux 2021, 14, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, H. Pola Dan Prospek Pengembangan Ternak Kambing Di Kawasan Agropolitan Kecamatan Kumpeh Ulu Kabupaten Muaro Jambi Provinsi Jambi. In Proceedings of the Seminar Nasional Hasil Penelitian/Pengkajian Spesifik Lokasi, Jambi, Indonesia, 23–24 November 2005; Peran, Teknologi Pertanian dalam Mendukung Revitalisasi Pertanian di Provinsi Jambi. BPTP: Jambi, Indonesia, 2006; pp. 490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumastut, R.I.; Mukhzarudfa, M. Jambi Ecotourism Development Model: Reviewed from Budget and Performance Commitment. In CELSciTech towards Downstream and Commercialization of Research; Universitas Muhammadiyah Riau: Pekanbaru, Indonesia, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, R.S.; Syamsir. Local Government’s Integrity and Strategy in Tourism Development Based on Creative Economy in Kerinci Regency. In Proceedings of the 1st Tidar International Conference on Advancing Local. Wisdom Towards Global Megatrends, TIC 2020, Magelang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia, 21–22 October 2020; Rihardi, S.A., Wismaningtyas, T.A., Maulida, H., Arifina, A.S., Fadlurrahman, Eds.; European Alliance for Innovation: Magelang, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulmardi. Transmigrasi Di Provinsi Jambi: Kesejahteraan Dan Sebaran Permukiman Generasi Kedua Transmigran; Pena Persada: Banyumas, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Achmad, A.A.; Nurwati, R.N.; Mulyana, N. Intervensi Sosial Terhadap Pengembangan Masyarakat Lokal Di Daerah Transmigrasi Desa Topoyo. J. Public Policy 2019, 5, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, D.; Rusdi. Perkembangan Kehidupan Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat Transmigrasi Desa Perintis Di Rimbo Bujang Tahun (1975–2020). J. Kronologi 2021, 3, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, W.; Ciais, P.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, P. Annual Oil Palm Plantation Maps in Malaysia and Indonesia from 2001 to 2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyanti, D.; Hein, L.; Kroeze, C.; Zuhdi, M.; Saad, A. Scenarios for Withdrawal of Oil Palm Plantations from Peatlands in Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutiyo; Maharjan, K.L. Rural Development Policy in Indonesia. In Decentralization and Rural Development in Indonesia; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihatin, R.B. Revitalisasi Program Transmigrasi. Aspir. J. Masal. Masal. Sos. 2013, 4, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Aliakbar, M.; Syafitri, W. Analisis Perubahan Struktur Ekonomi Dan Penyerapan Tenaga Kerja Berdasarkan Pendekatan Shift Share, Input-Output Dan ARIMA Di Provinsi Jambi 2001–2016. Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa FEB UB 2019, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fitri, Y.; Amir, A.; Murdi, S.; Syafaruddin. Using Input-Output Analysis Approach to Identify the Role of Agricultural Sectors in Jambi Economy. Russ. J. Agric. Socioecon. Sci. 2019, 85, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlani; Sirajuddin, T. Rural Development Strategies in Indonesia: Managing Villages to Achieve Sustainable Development. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 447, p. 012066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, S.D.; Sunarti; Widyaliza, S. Expansion of Oil Palm Plantations and Forest Cover Changes in Bungo and Merangin Districts, Jambi Province, Indonesia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 24, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bartkowiak, N. The Diversity of Socioeconomic Development of Rural Areas in Poland in the Western Borderland and the Problem of Post-State Farm Localities. Oeconomia Copernic. 2017, 8, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Agricultural Productivity Growth, Rural Economic Diversity, and Economic Reforms: India, 1970–2000. Econ. Dev. Struct. Change 2004, 52, 509–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. A Spatial Typology for Settlement Pattern Analysis in Small Islands. GeoFocus. Int. Rev. Geogr. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 15, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zanden, E.H.; Levers, C.; Verburg, P.H.; Kuemmerle, T. Representing Composition, Spatial Structure and Management Intensity of European Agricultural Landscapes: A New Typology. Landsc. Urban. Plan 2016, 150, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiadi, E.; Kobayashi, S. Contiguous Spatial Classification: A New Approach on Quantitative Zoning Method. J. Geogr. Educ. 2000, 43, 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Topaloglou, L.; Kallioras, D.; Manetos, P.; Petrakos, G. A Border Regions Typology in the Enlarged European Union. J. Borderl. Stud. 2005, 20, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatama, R.A.; Rustiadi, E.; Widiatmaka, W.; Pravitasari, A.E. Physical Geographical Factors Leading to the Disparity of Regional Development: The Case Study of Java Island. Indones. J. Geogr. 2022, 54, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics of Jambi Province. Jambi Province in Figures 2022; Statistics of Jambi Province: Jambi, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Indonesia. Indeks. Pembangunan Manusia 2014 Metode Baru; Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyani, D.; Sumardi. Analisis Produk Domestik Regional Bruto (PDRB); Saddhono, K., Ed.; CV Djiwa Amarta Press: Surakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. The Concept of Economic Diversification in the Context of Response Measures. Technical Paper by the Secretariat. In Proceedings of the Bonn Climate Change Conference, Bonn, Germany, 16–26 May 2016; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germnay, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sukadi, A.; Sukadi, E. Does Economic Diversification Foster Resilience to Crises? Empirical Investigation. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.; Watson, P. Did Regional Economic Diversity Influence the Effects of the Great Recession? Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 1824–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuty, A.A.S.A.; Tribhuwaneswari, A.B.; Zulkarnain, L. Analysis of Settlement Availability at Manyar Economic District Strategic Area of Gresik Regency. Kawistara 2021, 11, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutaali, L. Study of the Development of Rural Areas Kulonprogo District (Locating a New Growth Center). Tunas Geogr. 2021, 9, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics 22 Algorithms; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Firoz, M.C.; Banerji, H.; Sen, J. A Methodology to Define the Typology of Rural Urban Continuum Settlements in Kerala. J. Reg. Dev. Plan. 2014, 3, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Budiyantini, Y.; Pratiwi, V. Peri-Urban Typology of Bandung Metropolitan Area. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinsungnoen, T.; Kaoungku, N.; Durongdumronchai, P.; Kerdprasop, K.; Kerdprasop, N. The Clustering Validity with Silhouette and Sum of Squared Errors. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Industrial Application Engineering 2015 (ICIAE2015), Fukuoka, Japan, 28–31 March 2015; The Institute of Industrial Applications Engineers, Japan: Kitakyushu, Japan, 2015; pp. 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Indonesia. Produk Domestik Regional Bruto (Milyar Rupiah), 2000–2013. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/52/75/1/produk-domestik-regional-bruto.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Statistics Indonesia. [Seri 2010] Produk Domestik Regional Bruto (Milyar Rupiah), 2010–2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/52/286/1/-seri-2010-produk-domestik-regional-bruto-.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Statistics Indonesia. Laju Pertumbuhan Produk Domestik Regional Bruto Atas Dasar Harga Konstan 2000 (Persen), 2000–2013. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/52/652/1/laju-pertumbuhan-produk-domestik-regional-bruto-atas-dasar-harga-konstan-2000.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Statistics Indonesia. [Seri 2010] Laju Pertumbuhan Produk Domestik Regional Bruto Per Kapita Atas Dasar Harga Konstan 2010 (Persen), 2011–2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/52/296/1/-seri-2010-laju-pertumbuhan-produk-domestik-regional-bruto-per-kapita-atas-dasar-harga-konstan-2010.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Statistics Indonesia. [Seri 2010] Produk Domestik Regional Bruto Per Kapita (Ribu Rupiah), 2010–2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/52/288/1/-seri-2010-produk-domestik-regional-bruto-per-kapita.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Hill, H.; Resosudarmo, B.P.; Vidyattama, Y. Economic Geography of Indonesia: Location, Connectivity, and Resources. In Reshaping Economic Geography in East Asia; Huang, Y., Magnoli Bocchi, A., Eds.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, J.; Arai, S.W. Evolutionary Change in the Oil Palm Plantation Sector in Riau Province, Sumatra. In The Palm Oil Controversy in Southeast Asia: A Transnational Perspective; Pye, O., Bhattacharya, J., Eds.; ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute: Singapore, 2012; pp. 76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Indonesia. Indeks Pembangunan Manusia menurut Provinsi 1996–2013. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/26/202/1/indeks-pembangunan-manusia-menurut-provinsi.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Anggraini, E.; Rustiadi, E.; Syuaib, M.F.; Mulyati, H.; Widyastutik; Indrawan, R.D.; Djuanda, B.; Tonny, F.; Sjaf, S.; Faqih, A.; et al. Revitalisasi Ekonomi Perdesaan Pasca COVID-19. Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat; IPB University: Bogor, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General of Estate Crops. Tree Crop. Estate Statistics of Indonesia 2018–2020 (Palm Oil); Gartina, D., Sukriya, R.L.L., Eds.; Directorate General of Estate Crops: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rustiadi, E.; Barus, B.; Iman, L.S.; Mulya, S.P.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Antony, D. Land Use and Spatial Policy Conflicts in a Rich-Biodiversity Rain Forest Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. In Exploring Sustainable Land. Use in Monsoon Asia; Himiyama, Y., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Indonesia. Indonesian Oil Palm Statistics 2019; Sub-directorate of Estate Crops Statistics, Ed.; Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, T.G.; Nurmalina, R.; Rifin, A. Factors Determining Profit of Rubber and Oil Palm Smallholders in Batanghari, Jambi. J. Ind. Beverage Crops 2013, 4, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, E. Financial Feasibility Study of Smallholder Oil Palm in Muaro Jambi District, Jambi. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 583, p. 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitza, C.; Krishna, V.V.; Alamsyah, Z.; Qaim, M. The Economics Behind an Ecological Crisis: Livelihood Effects of Oil Palm Expansion in Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, J.; Yulmardi, Y.; Hardiani, H. Food Crops-Based and Horticulture-Based Villages Potential as Growth Center Villages in Jambi Province, Indonesia. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, G. Socio-Economic Resilience of Natural Resource Dependent Communities; University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pelkki, M.; Sherman, G. Forestry’s Economic Contribution in the United States, 2016. For. Prod. J. 2020, 70, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, T.W. Economic Perspectives on Land Use Change and Leakage. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 075012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMPLAN Data Team. MRIO vs. Larger Study Area: Leakage, Aggregation Bias, and Other Considerations. Available online: https://support.implan.com/hc/en-us/articles/115002799373-Size-of-Your-ImpactQuestions-Concerns-about-Small-vs-Large-Study-Regions (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Cameron, J. Enterprise Innovation and Economic Diversity in Community Supported Agriculture: Sustaining the Agricultural Commons. In Making Other Worlds Possible: Performing Diverse Economies; Roelvink, G., St. Martin, K., Gibson-Graham, J.K., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kühn, M. Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munibah, K.; Widiatmaka; Widjaja, H. Spatial Autocorrelation on Public Facility Availability Index with Neighborhoods Weight Difference. J. Reg. City Plan. 2018, 29, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legiani, W.H.; Lestari, R.Y.; Haryono. Transmigrasi Dan Pembangunan Di Indonesia. Hermeneut. J. Hermeneut. 2018, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Desa Pembangunan Daerah Tertinggal dan Transmigrasi. Transmigrasi Masa Doeloe, Kini Dan Harapan Kedepan; Kemendes PDTT: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015.

- Junaidi; Rustiadi, E.; Sutomo, S.; Juanda, B. Pengembangan Penyelenggaraan Transmigrasi Di Era Otonomi Daerah: Kajian Khusus Interaksi Permukiman Transmigrasi Dengan Desa Sekitarnya. J. Visi Publik 2012, 9, 522–534. [Google Scholar]

- Wira, N. Pemanfaatan Modal Sosial Sebagai Strategi Bertahan Hidup Komunitas Terdampak Pembangunan: Studi Penarik Ketek Terdampak Pembangunan Jembatan Di Kecamatan Pelayangan Kota Jambi; Universitas Andalas: Padang, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sabajo, C.R.; le Maire, G.; June, T.; Meijide, A.; Roupsard, O.; Knohl, A. Expansion of Oil Palm and Other Cash Crops Causes an Increase of the Land Surface Temperature in the Jambi Province in Indonesia. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 4619–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, M.; Sibhatu, K.T.; Siregar, H.; Grass, I. Environmental, Economic, and Social Consequences of the Oil Palm Boom. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, T.; Meijide, A.; Stiegler, C.; Kusuma, A.P.; Knohl, A. The Influence of Surface Roughness and Turbulence on Heat Fluxes from an Oil Palm Plantation in Jambi, Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 149, p. 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, L.P.; Hergoualc’h, K.; Smith, J.U.; Verchot, L. Conversion of Intact Peat Swamp Forest to Oil Palm Plantation: Effects on Soil. CO2 Fluxes in Jambi, Sumatra; CIFOR Wokring Paper 110; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, K.; Kunz, Y.; Rosyani, I.; Faust, H. Environmental Governance Meets Reality: A Micro-Scale Perspective on Sustainability Certification Schemes for Oil Palm Smallholders in Jambi, Sumatra. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 33, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharja, S.; Marimin; Machfud; Papilo, P.; Safriyana; Massijaya, M.Y.; Asrol, M.; Darmawan, M.A. Institutional Strengthening Model of Oil Palm Independent Smallholder in Riau and Jambi Provinces, Indonesia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napitupulu, D.; Ernawati, H.D.; Elwamendri, E.; Yanita, M.; Fauzia, G. Comparative Analysis between Smallholder and Partnership Oil Palm Farming System in Jambi Province. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 336, p. 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiani, E.; Mara, A.; Nainggolan, D.S. Peranan Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Dalam Pembangunan Ekonomi Wilayah Di Kabupaten Muaro Jambi. J. Ilm. Sosio-Ekon. Bisnis 2013, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mara, A.; Fitri, Y. Dampak Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Rakyat Terhadap Pendapatan Wilayah Desa (PDRB) Di Provinsi Jambi. J. AGRISEP Kaji. Masal. Sosial. Ekon. Pertan. Dan Agribisnis 2013, 12, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wahyudi, A.; Tan, S.; Hidayat, M.S. Strategi Pengembangan Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Di Provinsi Jambi. J. Paradig. Ekon. 2022, 17, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, E.M.M.; Siregar, H.; Juanda, B. Peranan Kelapa Sawit Dalam Perekonomian Daerah Provinsi Jambi: Analisis Input-Output Tahun 2010. JAM J. Apl. Manaj. 2014, 12, 671–678. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, A.; Amir, A.; Junaidi; Hidayat, S. Change of Economic Structure in Jambi Province: Input–Output Model Approach. Sci. Res. J. (SCIRJ) 2019, 7, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, H. Urban Futures in Planning, Policy and Regional Science: Are We Entering a Post-Urban World? Built Environ. 2014, 40, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdi. Kemitraan Sebagai Kunci Hubungan Harmonis. In Kemitraan Kunci Kesuksesan Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit (PIR BUN—PIR NES—PIR TRANS—PIR KKPA); Media Perkebunan, Ed.; Media Perkebunan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 106–113. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Variables | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2020 | ||

| 1. | Built-up area (%) | Bua11 | Bua20 |

| 2. | Oil palm plantation (%) | Oilplant11 | Oilplant20 |

| 3. | Other industrial crop plantations (%) | Othplant11 | Othplant20 |

| 4. | Dryland agriculture (%) | Dryagr11 | Dryagr20 |

| 5. | Shrub, grassland, bare land (%) | Shrub11 | Shrub20 |

| 6. | Forest cover (%) | Forest11 | Forest20 |

| 7. | Water body (%) | Water11 | Water20 |

| 8. | Economic diversity index | Dividx11 | Dividx20 |

| 9. | Infrastructure index | Infidx11 | Infidx20 |

| 10. | Transmigration village (y/n) | Tmigrat11 | Tmigrat20 |

| 11. | Multiethnic village (y/n) | Ethnic11 | Ethcnic20 |

| Year | Variable | Cluster | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 2011 | Built-up area | high | |||||

| Oil palm plantation | medium | ||||||

| Other industrial crops | medium | ||||||

| Dryland agriculture | low | low | high | medium | medium | medium | |

| Shrub, grassland, bare land | medium | ||||||

| Forest cover | low | medium | |||||

| Water body | high | ||||||

| Diversity index | very high | high | medium | slightly low | low | very low | |

| Infrastructure index | very high | high | medium | slightly low | low | very low | |

| Transmigration village | mostly not | mostly yes | mostly not | mostly not | mostly not | mostly not | |

| Multiethnic village | mostly yes | mostly yes | mostly yes | partly yes | partly yes | mostly not | |

| Member (%) | 6.4 | 14.2 | 49.6 | 7.2 | 4.3 | 18.3 | |

| Village type | Highly developed urban villages | Higher-developed mixed plantation transmigration villages | Moderately developed dryland agriculture villages | Slightly lowly developed tidal/backswamp villages | Lowly devel-oped dryland agricultural villages | Minimally developed forest villages | |

| 2020 | Built-up area | high | |||||

| Oil palm plantation | high | low | low | ||||

| Other industrial crops | low | low | high | ||||

| Dryland agriculture | high | ||||||

| Shrub, grassland, bare land | low | low | low | high | |||

| Forest cover | medium | ||||||

| Water body | high | ||||||

| Diversity index | very high | high | medium | slightly low | slightly low | low | |

| Infrastructure index | very high | high | medium | slightly low | slightly low | low | |

| Transmigration village | mostly not | mostly yes | mostly not | mostly not | mostly not | mostly not | |

| Multiethnic village | mostly yes | mostly yes | mostly yes | mostly yes | mostly yes | partly yes | |

| Member (%) | 9.9 | 15.6 | 8.4 | 27.5 | 6.0 | 32.6 | |

| Village type | Highly developed urban villages | Higher-developed oil palm plantation transmigration villages | Moderately developed dryland agriculture villages | Slightly lowly developed industrial crop villages | Slightly lowly developed tidal/backswamp villages | Lowly-developed forest villages | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rustiadi, E.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Priatama, R.A.; Singer, J.; Junaidi, J.; Zulgani, Z.; Sholihah, R.I. Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Land 2023, 12, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12051059

Rustiadi E, Pravitasari AE, Priatama RA, Singer J, Junaidi J, Zulgani Z, Sholihah RI. Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Land. 2023; 12(5):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12051059

Chicago/Turabian StyleRustiadi, Ernan, Andrea Emma Pravitasari, Rista Ardy Priatama, Jane Singer, Junaidi Junaidi, Zulgani Zulgani, and Rizqi Ianatus Sholihah. 2023. "Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia" Land 12, no. 5: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12051059

APA StyleRustiadi, E., Pravitasari, A. E., Priatama, R. A., Singer, J., Junaidi, J., Zulgani, Z., & Sholihah, R. I. (2023). Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Land, 12(5), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12051059