Natural Protected Areas within Cities: An International Legislative Comparison Focused on Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The emergence of cities: in Nordic countries, urbanization began to develop during the Middle Ages, with the emergence of trading cities and universities, while in eastern European countries, urbanization began later, in the 19th century, along with the industrialization process.

- Post-industrial urban evolution: in Nordic countries, post-industrial urban transformation has been characterized by the regeneration of abandoned industrial areas into modern and sustainable housing and business areas. In contrast, in eastern European countries, post-industrial urban transformation has often been slowed down or blocked by a lack of resources and economic problems [23].

- Urban size and density: Nordic countries generally have smaller and denser cities than eastern European countries. On the other hand, in eastern Europe, the tendency to decrease the area and density of cities, also known as “shrinking cities”, is becoming more and more common, due to a decrease in population.

- The evolution of public policy: while Nordic countries had a stable democratic development in the 20th century, eastern European countries were under communist regimes for several decades, which had a significant impact on their economic and cultural development.

3. Results

3.1. Critical Analysis of Legislative Acts and Planning Instruments of Urban Protected Areas in the Analyzed EU Countries

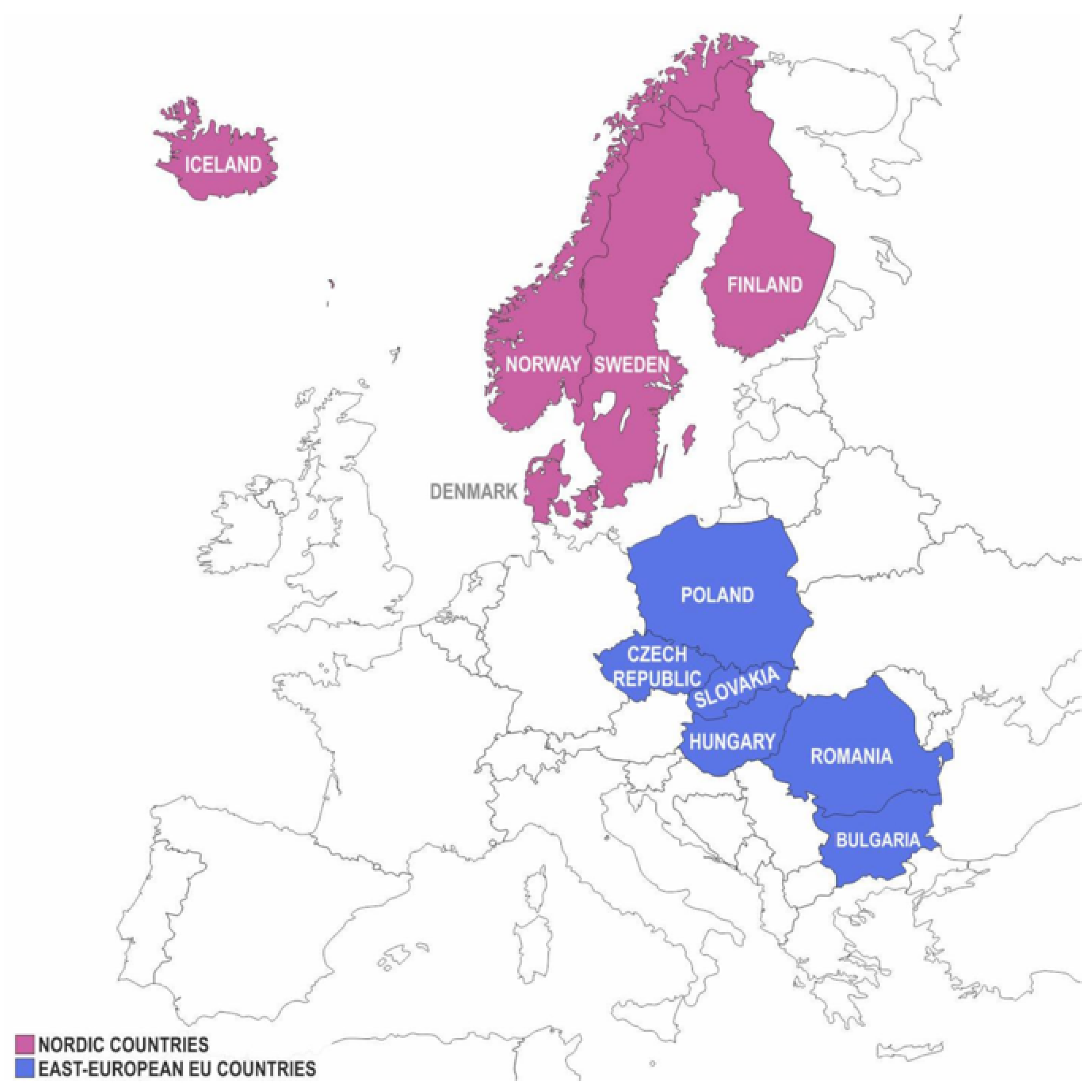

3.1.1. Nordic Countries—Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden

Denmark

Finland

Iceland

Norway

Sweden

3.1.2. Eastern European Countries—Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Romania

Bulgaria

Czech Republic

Hungary

Poland

Slovakia

Romania

3.2. Comparison of the Existing Models and the Approach to the Problem of Conservation of Natural Protected Areas in Urban Areas in the Nordic Countries and in the Eastern European Countries

4. Discussion

4.1. The Significance of Results

4.2. The Inner Validation of Results

4.3. The External Validation of Results

4.4. The Importance of Results

4.5. Summary of the Study Limitations and Directions for Overcoming Them in the Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iojă, C.; Breuste, J. Urban Protected Areas and Urban Biodiversity. In Making Green Cities; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Iojă, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Sîrodoev, I.; Ianoş, I. Trends in the national and regional transitional dynamics of land cover and use changes in Romania. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepción, E.D. Urban sprawl into Natura 2000 network over Europe. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crăciun, C.; Gârjoabă, A.-I. Methods of Approaching Natural Protected Areas from the Towns of Europe. Rev. Urbanism. Arhit. Construcții 2022, 13, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, A.M.; Onose, D.A.; Sandric, I.C.; Dosiadis, E.A.; Petropoulos, G.P.; Gavrilidis, A.A.; Faka, A. Using GEOBIA and Vegetation Indices to Assess Small Urban Green Areas in Two Climatic Regions. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.; Cook, C. Public and private protected areas can work together to facilitate the long-term persistence of mammals. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchet, M.A.; Rega, C.; Lasseur, R.; Georges, D.; Paracchini, M.-L.; Renaud, J.; Stürck, J.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verburg, P.H.; Verkerk, P.J.; et al. Ecosystem service supply by European landscapes under alternative land-use and environmental policies. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, M.; Zywica, P.; Subiros, J.V.; Brodka, S.; Macias, A. How do the surrounding areas of national parks work in the context of landscape fragmentation? A case study of 159 protected areas selected in 11 EU countries. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Ramos, J.; Feria-Toribio, J.M. Assessing the effectiveness of protected areas against habitat fragmentation and loss: A long-term multi-scalar analysis in a mediterranean region. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 64, 126072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausche, B. Guidelines for Protected Areas Legislation; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Protected Areas in Europe—An Overview; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Niemela, J. Linking ecological and social systems in cities: Urban planning in Finland as a case. Biodivers. Conservat. 2005, 14, 1947–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedreheim, G.E.; Blanco, E. Co-management of protected areas to alleviate conservation conflicts: Experiences in Norway. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, C. Pluridisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity—Methods of Researching the Metabolism of the Urban Landscape. In Planning and Designing Sustainable and Resilient Landscapes; Springer: Dordrecht, Holland, 2014; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, M.A. Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Contexts: A Case Study of Malmö. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Mierzejewska, L.; Mitrea, A.; Drachal, K.; Tache, A.V. Dynamics of Open Green Areas in Polish and Romanian Cities During 2006–2018: Insights for Spatial Planners. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, T.; Jankovska, I.; Boștenaru Dan, M. Urban green infrastructure: The role of urban agriculture in city resilience. Urbanism. Arhit. Construcții 2018, 9, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Petroni, M.L.; Siqueira-Gay, J.; Gallardo, A.L.C.F. Understanding land use change impacts on ecosystem services within urban protected areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boștenaru, M.; Crăciun, C. Creativity and Spatial Urban and Landscape Perception in Architectural Imagination. In Proceedings of the 9th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Communicative Action & Transdisciplinarity in the Ethical Society, Lumen, Romania, 24–25 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blaszke, M.; Nowak, M.J. Objectives of spatial planning in selected Central and Eastern European countries. Analysis of selected case studies. Ukr. Geogr. J. 2022, 4, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheci, R.M.; Ianoş, I.; Sârbu, C.N.; Sorensen, A.; Saghin, I.; Secăreanu, G. Assessing environmental fragility in a mining area for specific spatial planning purposes. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2019, 27, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Štrbac, S.; Veselinović, G.; Antić, N.; Stojadinović, S.; Stojić, N.; Živanović, N.; Kašanin-Grubin, M. Applicability of the PA-BAT+ in the evaluation of values of urban protected areas. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.L.; Alvim, A.T.B.; Schröder, J. Ecosystem Services and Urban Planning: A Review of the Contribution of the Concept to Adaptation in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Ministry of the Environment. The Planning Act in Denmark Consolidated—Act No. 813 of 21 June 2007; Danish Ministry of the Environment: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Ministry of the Environment. The Nature Protection Law—Act No. 951 of 3 June 2013; Danish Ministry of the Environment: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Ministry of Justice. Land Registration Act—Act No. 622 of 15 September 1986; Danish Ministry of Justice: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish Ministry of the Environment. The Land Use and Building Act No. 132 of 1999; Finnish Ministry of the Environment: Helsinki, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lidmo, J.; Bogason, A.; Turunen, E. The Legal Framework and National Policies for Urban Greenery and Green Values in Urban Areas A Study of Legislation and Policy Documents in the Five Nordic Countries and Two European Outlooks; Nordregio Report: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish Ministry of the Environment. The Finnish Biodiversity Action Plan 2013–2020; Finnish Ministry of the Environment: Helsinki, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Iceland. Planning and Building Act No. 73/1997, No. 135/1997 and No. 58/1999; Government of Iceland: Reykjavík, Iceland, 1999.

- Government of Iceland. The Nature Conservation Act—Act No. 44 of 22 March 1999; Government of Iceland: Reykjavík, Iceland, 22 March 1999.

- Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment. Act of 27 June 2008 No. 71 Relating to Planning and the Processing of Building Applications (the Planning and Building Act); Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment: Oslo, Norway, 27 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment. The Nature Diversity Act—Act of 19 June 2009 No.100 Relating to the Management of Biological, Geological and Landscape Diversity); Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment: Oslo, Norway, 19 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment. Act on Nature Areas in Oslo and Nearby Municipalities, 2009; Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Environment Agency. Planning Green Structures in Cities and Towns, 2014; Norwegian Environment Agency: Oslo Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Primack, R. Designing Protected Areas. In Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. The Planning and Building Act, 2010; Swedish National Board of Housing: Malmö, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Ministry of the Environment. The Environmental Code, 2000; Swedish Ministry of the Environment: Malmö, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Regional Development—Bulgaria. National Concept for Spatial Development 2013–2025, 2012; National Centre for Regional Development—Bulgaria: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Bulgarian Official Gazette. Spatial Development Act No. 1/2001; The Bulgarian Official Gazette: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The Bulgarian Official Gazette. Regional Development Act No. 50/2008; The Bulgarian Official Gazette: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Bulgarian Official Gazette. Environmental Protection Act No. 91/2002; The Bulgarian Official Gazette: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- The Bulgarian Official Gazette. Protected Areas Act No. 133/1998; The Bulgarian Official Gazette: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Bulgarian Official Gazette. Biodiversity Act No. 77/2002; The Bulgarian Official Gazette: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- The Czech Government. Spatial Development Policy of the Czech Republic 2008, Approved by Government Resolution No. 929 of 20 July 2009; The Czech Government: Prague, Czech Republic, 20 July 2009.

- The Czech Parliament. Act of 14th March 2006 on Town and Country Planning and Building Code (Building Act); The Czech Parliament: Prague, Czech Republic, 20 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Czech Government. Act No. 17/1992 on the Environment; The Czech Government: Prague, Czech Republic, 1992.

- The Czech Government. Act No. 114/1992 on Nature and Landscape Protection; The Czech Government: Prague, Czech Republic, 1992.

- The Urban Planning Department of Budapest City Hall. The Long-Term Urban Development Concept of Budapest 2030 [Hosszü Távü Városfejlesztési Koncepciő]; The Urban Planning Department of Budapest City Hall: Budapest, Hungary, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.J.; Brelik, A.; Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Śpiewak-Szyjka, M.; Przedańska, J. Spatial Conflicts Concerning Wind Power Plants—A Case Study of Spatial Plans in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Foryś, I.; Nowak, M.J.; Mickiewicz, B. Selected Characteristics of Municipalities as Determinants of Enactment in Municipal Spatial Plans for Renewable Energy Sources—The Case of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaton Development Council. Balaton Territorial Development Concept 2014—2030, 2013; Balaton Development Council: Siófok Hungary, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Parliament of Hungary. Act XXI of 1996 on Regional Development and Regional Planning; The Parliament of Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- The Parliament of Hungary, Act LXXVIII 1997 on the Development and Protection of the Built Environment; The Parliament of Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 1997.

- The Parliament of Hungary. Act XXVI 2003 on the National Spatial Plan; The Parliament of Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Ministry of Economic Development and Technology. The Spatial Planning and Development Act of March 27, 2003; Polish Ministry of Economic Development and Technology: Krakow, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Poland. The National Spatial Development Concept 2030; The Government of Poland: Krakow, Poland, 2010.

- The Government of Poland. Act of 3 October 2008 on the provision of information on the environment and its protection, public participation in environmental protection and environmental impact assessments. J. Laws 2008, 199, 1227. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport. Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic; Ministry of Transport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Izakovicova, Z.; Swiader, M. Building ecological networks in Slovakia and Poland. Ekologia 2017, 36, 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kočická, E.; Diviaková, A.; Kočický, D.; Belaňová, E. Territorial system of ecological stability as a part of land consolidations (cadastral territory of Galanta—Hody, Slovak Republic). Ekologia 2018, 37, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, O.C.; Tache, A.V.; Petrişor, A.-I. Methodology for identifying the ecological corridors. Case study: Planning the brown bear corridors in the Romanian Carpathians. Rev. Verde/Green J. 2022, 1, 174–202. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Assembly of The Czechoslovak Socialistic Republic. The Act on Land-Use Planning and Building Order (Act 50/1976 Coll.); Federal Assembly of The Czechoslovak Socialistic Republic: Prague, Czechoslovak Republic, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- The National Council of the Slovak Republic. The Environmental Impact Assessment Act (Act 24/2005 Coll.); The National Council of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The National Council of the Slovak Republic. Act on Nature and Landscape Protection (Act 543/1994 Coll.); The National Council of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- The Parliament of Romania. Law No. 350 of June 6, 2001 regarding Territorial Planning and Town Planning; The Parliament of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grădinaru, S.; Paraschiv, M.; Iojă, C.; Van Vliet, J. Conflicting interests between local governments and the European target of no net land take. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 142, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, O.C.; Petrişor, A.-I. Green infrastructure and spatial planning: A legal framework. Olten. Stud. Şi Comunicări Ştiinţele Nat. 2021, 37, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Romania. Decision No. 525 of June 27, 1996 for the Approval of the General Urban Planning Regulation; The Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 27 June 1996.

- The Parliament of Romania. Law No. 137 of December 29, 1995—Environmental Protection Law; The Parliament of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Romania. Emergency Ordinance No. 195/2005 on Environmental Protection; The Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Parliament of Romania. Law No. 24 of January 15, 2007 Regarding the Regulation and Administration of Green Spaces in the Urban Areas; The Parliament of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Iojă, C.; Breuste, J.; Vânău, G.; Hossu, C.; Niță, M.; Onose, D.; Slave, A. Bridging the People-Nature Divide using the Participatory Planning of Urban Protected Areas. In Making Green Cities; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Iojă, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kadar, M.; Benedek, I. The Branding and Promotion of Cultural Heritage. Case Study About the Development and Promotion of a Touristic Heritage Route in the Carpathian Basin. J. Media Res. 2017, 10, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.-I. Are public administrations the only ones responsible for organizing the administration of green spaces within the localities? An assessment of the perception of the citizens of Constanţa municipality in the context of sustainable development. Technium Social Sci. J. 2022, 31, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, J.J.; Shahbol, N.; Maynard, J.; Grill, G.; Higgins, J.; Tracey, D.; Thieme, M. Safeguarding Free-Flowing Rivers: The Global Extent of Free-Flowing Rivers in Protected Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M.G.; Elmo, G.C.; Arcese, G.; Cappelletti, G.M.; Martucci, O. Accessible Tourism in Protected Natural Areas: An Empirical Study in the Lazio Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Andrei, M. How efficient is the protection of biodiversity through natural protected areas in Romania? Olten. Stud. Şi Comunicări Ştiinţele Nat. 2019, 35, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gârjoabă, A.-I.; Crăciun, C. Supporting the Process of Designing and Planning Heritage and Landscape by Spatializing Data on a Single Support Platform. Case Study: Romania. Rev. Românească Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2022, 14, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, C. Urban Metabolism. An Unconventional Approach to the Urban Organism [Metabolismul Urban. O Abordare Neconvențională a Organismului Urban]; “Ion Mincu” University Publisher: Bucharest, Romania, 2008; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Geneletti, D.; Cortinovis, C.; Zardo, L.; Esmail, B.A. Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities. In Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N.; Ali, N.; Kettunen, M.; MacKinnon, K. Editorial Essay: Protected areas and the sustainable development goals. Parks 2017, 23, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, C.; Gârjoabă, A.-I. Integration of Instruments for the Protection of Natural Protected Areas in Urban and Biodiversity Strategies and in Urban Planning Regulations. In Proceedings of the World LUMEN Congress, Iasi, Romania, 26–30 May 2021; Volume 17, pp. 140–158. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gârjoabă, A.-I.; Crăciun, C.; Petrisor, A.-I. Natural Protected Areas within Cities: An International Legislative Comparison Focused on Romania. Land 2023, 12, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071279

Gârjoabă A-I, Crăciun C, Petrisor A-I. Natural Protected Areas within Cities: An International Legislative Comparison Focused on Romania. Land. 2023; 12(7):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071279

Chicago/Turabian StyleGârjoabă, Atena-Ioana, Cerasella Crăciun, and Alexandru-Ionut Petrisor. 2023. "Natural Protected Areas within Cities: An International Legislative Comparison Focused on Romania" Land 12, no. 7: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071279

APA StyleGârjoabă, A.-I., Crăciun, C., & Petrisor, A.-I. (2023). Natural Protected Areas within Cities: An International Legislative Comparison Focused on Romania. Land, 12(7), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071279