Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

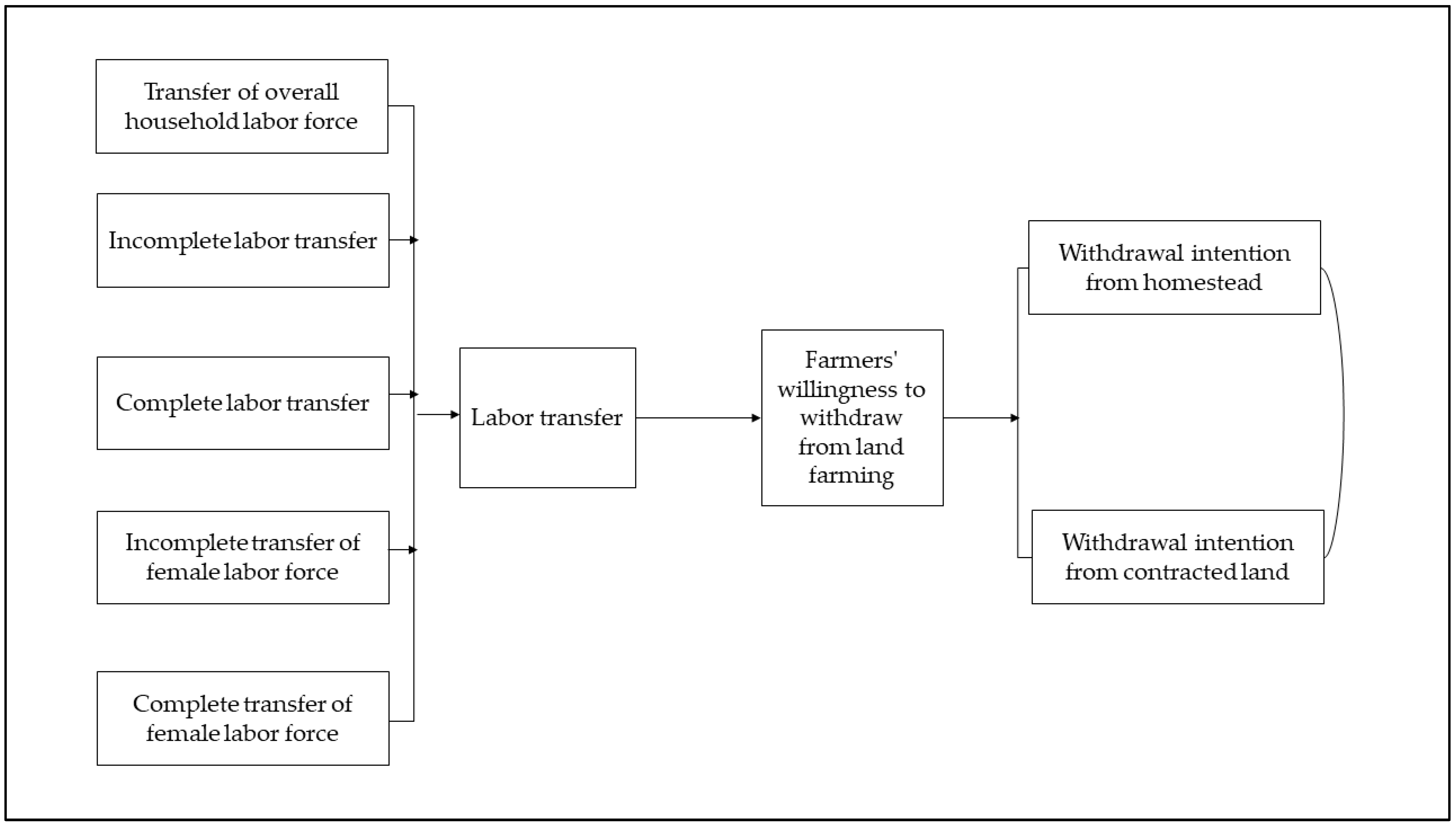

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

2.1. Correlation Effect of Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Contracted Land and the Homestead

2.2. The Impact of Labor Force Transfer on the Willingness to Withdraw from Farmers’ Contracted Land and the Homestead

2.3. The Impact of Different Types of Labor Transfer within the Family on the Willingness to Quit the Farmer’s Contracted Land and the Homestead

2.4. The Impact of the Female Labor Force Transfer on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Contracted Land and the Homestead

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Key Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Other Explanatory Variables

3.3. Key Explanatory Variables

4. Results

4.1. The Correlation Effect of Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Land

4.2. The Correlation Effect of Labour Transfer to Withdraw from Land

4.3. The Effect of Other Explanatory Variables on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Land

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (i)

- Because of the current low willingness of farmers to withdraw from contracted land and homesteads, the government should, on the one hand, steadily make forward-looking institutional arrangements for land withdrawal to lay the institutional foundation for farmers to withdraw from contracted land and homesteads in a gradual and orderly manner. On the one hand, the government must have historical patience and responsibility for the withdrawal of farmers’ contracted land and homesteads, respect the wishes of farmers, and resolutely prevent farmers from being “excluded from the land”.

- (ii)

- Therefore, the willingness to withdraw from the homestead needs to be premised on the willingness to withdraw from contracted land, or the willingness to withdraw from contracted land can strengthen the willingness to withdraw from the homestead. As the correlation effect between farmers’ willingness to withdraw from contracted land and their willingness to withdraw from the homestead, the two should be placed within the framework of the rural land withdrawal system, and the practical connection and mutual promotion of the homestead withdrawal policy and the contracted land withdrawal policy should be strengthened. Farmers voluntarily withdraw from contracted land as the guide, establish a policy support system that supports the effective combination of contracted land withdrawal and homestead withdrawal, and guide farmers to withdraw from contracted land and the homestead in an orderly manner.

- (iii)

- The government should provide farmers with more non-agricultural jobs through the secondary and tertiary industries, improve the vocational skills training to enhance the competitiveness of farmers ‘ non-agricultural employment and promote the development of family labor from incomplete transfer to complete the transfer. On the other hand, the government should take the complete labor transfer of households as a reference to improve the targeting of the land exit policy, improve the land exit policy supported by employment resettlement, and use “industry” to return “land” to improve the exit of farmers’ contracted land and homestead will.

- (iv)

- Since the prominent role of female family labor transfers on farmers’ willingness to quit contracted land and the homestead, the government should increase the skills training for rural women’s off-farm employment and promote participation. At the same time, it should be committed to creating a better job environment for rural women. A more equitable and improved non-agricultural employment environment will advance in the long-term and stable transfer of the female labor force, reduce farmers’ dependence on contracted land and homesteads, and increase their willingness to withdraw from contracted land and homesteads.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen, L.-S.; Sorgho, R.; Mank, I.; Nayna Schwerdtle, P.; Agure, E.; Bärnighausen, T.; Danquah, I. Home Gardening in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review on Practices and Nutrition Outcomes in Rural Burkina Faso and Kenya. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Ullah, H.; Himanshu, S.K.; Datta, A. Farmers’ Perceptions, Determinants of Adoption, and Impact on Food Security: Case of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Coastal Bangladesh. Clim. Policy 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, Y.; Owusu-Sekyere, E. Improving the Income Status of Smallholder Vegetable Farmers through a Homestead Food Garden Intervention. Outlook Agric. 2019, 48, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, B.Y.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Emmanuel, D.; Elizabeth, T.B. The Impact of the Homestead Food Garden Programme on Food Security in South Africa. Food Sec. 2018, 10, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z. Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: A Survey in Zhejiang, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Sun, X. Does Labor Migration Affect Rural Land Transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hu, M.; Wu, Y. Rural Land Transfer and Urban Settlement Intentions of Rural Migrants: Evidence from a Rural Land System Reform in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Chen, J.; Wei, L. The Strength of Culture: Acculturation and Urban-Settlement Intention of Rural Migrants in China. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Factors Influencing Farmers’ Willingness and Behavior Choices to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads in China. Growth Chang. 2022, 53, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Land Use Policy as an Instrument of Rural Resilience—The Case of Land Withdrawal Mechanism for Rural Homesteads in China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 87, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, L. Does Cognition Matter? Applying the Push-Pull-Mooring Model to Chinese Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ni, X.; Liang, Y. The Influence of External Environment Factors on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Wuhan and Suizhou City in Central China. Land 2022, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhena, D.H.; Freed, R.; Maredia, K.M. Home Gardens: A Promising Approach to Enhance Household Food Security and Wellbeing. Agric. Food Secur. 2013, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. A China Paradox: Migrant Labor Shortage amidst Rural Labor Supply Abundance. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2010, 51, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. The Impact of Agricultural Labor Migration on the Urban–Rural Dual Economic Structure: The Case of Liaoning Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zheng, Y. How to Promote the Withdrawal of Rural Land Contract Rights? An Evolutionary Game Analysis Based on Prospect Theory. Land 2022, 11, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J. What Role(s) Do Village Committees Play in the Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads? Evidence from Sichuan Province in Western China. Land 2020, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Woods, M.; Fois, F. Rural Decline or Restructuring? Implications for Sustainability Transitions in Rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Rural Population Decline, Cultivated Land Expansion, and the Role of Land Transfers in the Farming-Pastoral Ecotone: A Case Study of Taibus, China. Land 2022, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, M.; Che, X.; Fang, F. Farmers’ Rural-To-Urban Migration, Influencing Factors and Development Framework: A Case Study of Sihe Village of Gansu, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Rada, N.; Qin, L.; Pan, S. Impacts of Migration on Household Production Choices: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.J.; Villaronte, R.K.; Yap, M.C.; Rosete, M.A. The Relationship between Rural-Urban Migration and the Agricultural Output of the Philippines. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2022, 3, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land Consolidation and Rural Revitalization in China: Mechanisms and Paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the World’s Countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Fu, C.; Kong, S.; Du, J.; Li, W. Citizenship Ability, Homestead Utility, and Rural Homestead Transfer of “Amphibious” Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Lin, C.; Lin, S.-H. Farmers’ Livelihood, Risk Expectations, and Homestead Withdrawal Policy: Evidence on Jinjiang Pilot of China. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2022, 26, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Post-Resettlement Support Policies, Psychological Factors, and Farmers’ Homestead Exit Intention and Behavior. Land 2022, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.A.; Abubakr, S.; Fischer, C. Factors Affecting Farm Succession and Occupational Choices of Nominated Farm Successors in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ling, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, L. How Does Rural Homestead Influence the Hukou Transfer Intention of Rural-Urban Migrants in China? Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Farmer Differentiation, Generational Differences and Farmers’ Behaviors to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Jiang, C.; Meng, L. Leaving the Homestead: Examining the Role of Relative Deprivation, Social Trust, and Urban Integration among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Sun, J. RETRACTED: Model of the Influencing Factors of the Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads in China: Application of Grounded Theory Method. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural Land System Reforms in China: History, Issues, Measures and Prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cloutier, S.; Li, H. Farmers’ Economic Status and Satisfaction with Homestead Withdrawal Policy: Expectation and Perceived Value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Westlund, H.; Klaesson, J. Report from a Chinese Village 2019: Rural Homestead Transfer and Rural Vitalization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lyu, P.; Cao, Y. Multi-Party Game and Simulation in the Withdrawal of Rural Homestead: Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 614–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GuoCheng, G.; XiaoTian, Z. Study on influencing factors of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from homestead from the perspective of intergenerational difference. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2018, 46, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Su, K.; Bi, G.; Li, Y. Farmers’ Willingness to Gather Homesteads and the Influencing Factors—An Empirical Study of Different Geomorphic Areas in Chongqing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Su, K.; Zhang, H.; Qu, X. The Impact of Farming Households’ Livelihood Vulnerability on the Intention of Homestead Agglomeration: The Case of Zhongyi Township, China. Land 2022, 11, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The Functional Value Evolution of Rural Homesteads in Different Types of Villages: Evidence from a Chinese Traditional Agricultural Village and Homestay Village. Land 2022, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChunLei, D.; XiaoFeng, Z.; ZhiFeng, J.; XiaoPing, L. Farmers’ willingness to withdraw from homestead in different economic area. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2018, 46, 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, A.; Martin, P.L.; Nagaar, R. Labor Shortages in Egyptian Agriculture. In Migration, Mechanization, and Agricultural Labor Markets in Egypt; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 21–44. ISBN 978-0-429-04710-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Dang, X.; Tong, Y.; Li, R. Functions, Motives and Barriers of Homestead Vegetable Production in Rural Areas in Ageing China. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, A.; Cai, F.; Chen, L. Discussion on establishment of exit mechanism for rural residential land. China Land Sci. 2009, 23, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.F.; Hu, Y.G.; He, A.Q.; Ni, N. The analysis based on the rural homestead withdrawal mode of the Logistic. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 31, 15542–15545. [Google Scholar]

- Kazukauskas, A.; Newman, C.; Clancy, D.; Sauer, J. Disinvestment, Farm Size, and Gradual Farm Exit: The Impact of Subsidy Decoupling in a European Context. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Hennessy, D.A.; Jensen, H.H.; Volpe, R.J. Technical Efficiency, Herd Size, and Exit Intentions in U.S. Dairy Farms. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaten, O. Factors Affecting Exit Intentions in Norwegian Sheep Farms. Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 150, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, A.; Zimmert, F. Structural Change in the Dairy Sector: Exit from Farming and Farm Type Change. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, H.; Rahman, A.; Qian, L.; Memon, W.H. Evaluating the Roles of the Farmer’s Cooperative for Fostering Environmentally Friendly Production Technologies-a Case of Kiwi-Fruit Farmers in Meixian, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Salam, M.; Sarkar, M.; Rouf, A.; Rahman, M.C.; Islam, S.; Rahman, M.; Khan, M.R.A.; Obaidulla, M.; Khatun, S. Availability and Price Volatility of Rice in Bangladesh: An Inter-Institutional Study in 2020. In Availability and Price Volatility of Rice, Potato and Onion in Bangladesh; Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology Division: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020; pp. 15–53. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Li, Z.; Yin, C. Response Mechanism of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital to the Compensation for Rural Homestead Withdrawal—Empirical Evidence from Xuzhou City, China. Land 2022, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Peng, W.; Huang, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Homestead Management in China from the “Separation of Two Rights” to the “Separation of Three Rights”: Visualization and Analysis of Hot Topics and Trends by Mapping Knowledge Domains of Academic Papers in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.K.; Bijman, J.; Kemp, R.; Omta, O.; Tsegaye, A. Contract Farming Configuration: Smallholders’ Preferences for Contract Design Attributes. Food Policy 2013, 40, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J.; Mugwagwa, I.; Trienekens, J. Typology of Contract Farming Arrangements: A Transaction Cost Perspective. Agrekon 2020, 59, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suza, M.K.; Hasan, S.S.; Ghosh, M.K.; Haque, M.E.; Turin, M.Z. Financial Security of Farmers through Homestead Vegetable Production in Barishal District, Bangladesh. Eur. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Chakraborty, T.K.; Al Mamun, A.; Kiaya, V. Land- and Water-Based Adaptive Farming Practices to Cope with Waterlogging in Variably Elevated Homesteads. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A Novel Framework for Rural Homestead Land Transfer under Collective Ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, P. Building the Homestead: Agriculture, Labour and Beer in South Africa’s Transkei; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-00-307345-1. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.; Wijaya, H. What Kind of Labour Regime Is Contract Farming? Contracting and Sharecropping in Java Compared. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, M.; Ni, P. Urbanization and Rural Development in the People’s Republic of China. In Cities of Dragons and Elephants: Urbanization and Urban Development in the People’s Republic of China and India; ADBI Working Paper 596; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S.T.; Otsuka, K. The Roles of Land Tenure Reforms and Land Markets in the Context of Population Growth and Land Use Intensification in Africa. Food Policy 2014, 48, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Lu, H.; Gao, Q.; Lu, H. Household-Owned Farm Machinery vs. Outsourced Machinery Services: The Impact of Agricultural Mechanization on the Land Leasing Behavior of Relatively Large-Scale Farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, P.G.M. Migrancy and the Differentiated Agrarian Landscapes: Land Use, Farming and the Reproduction of the Homestead in the Eastern Cape. In Migrant Labour after Apartheid: The Inside Story; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020; pp. 240–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, V.; Podikunju, B. Constraints Experienced by Homestead Vegetable Growers in Kollam District. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2021, 57, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, K.; Pain, A.; Khatri, D.B. Re-Reading Nepalese Landscapes: Labour, Water, Farming Patches and Trees. For. Trees Livelihoods 2020, 29, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. African Americans and the Southern Homestead Act. Great Plains Q. 2019, 39, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyu, L.; Yukun, G. Research on the Function Evolution and Driving Mechanism of Rural Homestead in Luxian County under the “Rural Revitalization”. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, E.; Dessein, J. Perceptions of a Small Farming Community on Land Use Change and a Changing Countryside: A Case-Study from Flanders. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2015, 22, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X. A Study on Factors Driving Rural Homestead Transfer in the Market Based on the Push and Pull Theory. Chin. Stud. 2023, 12, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of Rural–Urban Migration on Agricultural Transformation: A Case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Incomplete Urbanization and the Trans-Local Rural-Urban Gradient in China: From a Perspective of New Economics of Labor Migration. Land 2022, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabe, K.E.; Abbey, A.G.; Egyir, I.S.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Anim-Somuah, H. Impact of Contract Farming on Product Quality Upgrading: The Case of Rice in Togo. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 9, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Zhao, W. Using Risk System Theory to Explore Farmers’ Intentions towards Rural Homestead Transfer: Empirical Evidence from Anhui, China. Land 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N. Research on Legislative Issues Related to The Reform of Homestead Management System in Ningxia. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2022, 5, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olounlade, O.A.; Li, G.-C.; Kokoye, S.E.H.; Dossouhoui, F.V.; Akpa, K.A.A.; Anshiso, D.; Biaou, G. Impact of Participation in Contract Farming on Smallholder Farmers’ Income and Food Security in Rural Benin: PSM and LATE Parameter Combined. Sustainability 2020, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerche, J. The Farm Laws Struggle 2020–2021: Class-Caste Alliances and Bypassed Agrarian Transition in Neoliberal India. J. Peasant Stud. 2021, 48, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.N.; Waibel, H. The Role of Homestead Fish Ponds for Household Nutrition Security in Bangladesh. Food Sec. 2019, 11, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, A.; Osei, A.K.; Haselow, N.J.; Kroeun, H.; Uddin, A.; Quinn, V. Contribution of Homestead Food Production to Improved Household Food Security and Nutrition Status–Lessons Learned from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nepal and the Philippines. In International Symposium on Food and Nutrition Security: Food-based Approaches for Improving Diets and Raising Levels of Nutrition; FAO Headquarters: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Timaeus, V.H.; Ian, M. Household Composition and Dynamics in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: Mirroring Social Reality in Longitudinal Data Collection. In African Households; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-315-49753-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gartaula, H.; Patel, K.; Johnson, D.; Devkota, R.; Khadka, K.; Chaudhary, P. From Food Security to Food Wellbeing: Examining Food Security through the Lens of Food Wellbeing in Nepal’s Rapidly Changing Agrarian Landscape. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, A.; Pandey, P.; Nielsen, J.; Pries, A.; Spiro, D.; Davis, D.; Quinn, V.; Haselow, N. Combining Home Garden, Poultry, and Nutrition Education Program Targeted to Families with Young Children Improved Anemia among Children and Anemia and Underweight among Nonpregnant Women in Nepal. Food Nutr. Bull. 2017, 38, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siphesihle, Q.; Lelethu, M. Factors Affecting Subsistence Farming in Rural Areas of Nyandeni Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2020, 48, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, A.; Hoque, F.; Rahman, M.S.; Kiprop, E.; Shah, M. Determinants of Adoption of Homestead Gardening by Women and Effect on Their Income and Decision Making Power. J. Appl. Hortic. 2021, 23, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Asadullah, M.N.; Kambhampati, U. Feminization of Farming, Food Security and Female Empowerment. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 29, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundala, N.; Kinabo, J.; Jumbe, T.; Rybak, C.; Sieber, S. Does Homestead Livestock Production and Ownership Contribute to Consumption of Animal Source Foods? A Pre-Intervention Assessment of Rural Farming Communities in Tanzania. Sci. Afr. 2020, 7, e00252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.; Keus, H.J.; Ullah, M.H.; Kassam, L.; Phillips, M.; Beveridge, M. Investing in Carp Seed Quality Improvements in Homestead Aquaculture: Lessons from Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2016, 453, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.M.R.; Ahmed, M.M.; Ansari, A.; Khatun, M.; Kamal, T.B.; Afrad, M.S.I. Homestead Vegetable Gardening as a Source of Calorie Supplement at Ishurdi Upazila, Bangladesh. ISABB J. Food Agric. Sci. 2021, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Uddin, M.S.; Banik, S.C.; Goswami, B.K.; Kashem, M.A. Impact of Homestead Agroforestry on Socio-Economic Condition of the Respondents at Kamalganj Upazila of Moulvibazar District in Bangladesh. Asian J. Res. Agric. For. 2019, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, W.; LaRovere, R.; Mwabu, G.; Kassie, G.T. Adoption and Farm-Level Impact of Conservation Agriculture in Central Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 2517–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiburis, R.C.; Das, J.; Lokshin, M. A Practical Comparison of the Bivariate Probit and Linear IV Estimators. Econ. Lett. 2012, 117, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sarkar, A.; Xia, X.; Memon, W.H. Village Environment, Capital Endowment, and Farmers’ Participation in E-Commerce Sales Behavior: A Demand Observable Bivariate Probit Model Approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Qiao, J.; Xiang, D.; Peng, T.; Kong, F. Can Labor Transfer Reduce Poverty? Evidence from a Rural Area in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. The Impact of Land Transfer on Vulnerability as Expected Poverty in the Perspective of Farm Household Heterogeneity: An Empirical Study Based on 4608 Farm Households in China. Land 2022, 11, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U.; Singhal, S.; Tarp, F. Commodity Prices and Intra-Household Labor Allocation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.F.; Al-Omari, A.I. Multistage Ranked Set Sampling. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2002, 102, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, I. Multistage Sampling. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-44511-2. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, R.; Hou, L.; Jia, B.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, X. Effect of Policy Cognition on the Intention of Villagers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads. Land 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Niu, P.; Xiao, D. Decision-making of farmers to exit land contract management right and influencing factors under scenario simulation. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L. A Study on Shanghai Farmers’ Will of the Withdrawal from Homestead Based on the Perspective of Triadic Reciprocal Determinism; Beijing Language and Culture University Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 1327–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yong, Z.; Liu, S. Relationships between Labor Migration and Cropland Abandonment in Rural China from the Perspective of Village Types. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Yao, G. Impact of Land Fragmentation on Marginal Productivity of Agricultural Labor and Non-Agricultural Labor Supply: A Case Study of Jiangsu, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhong, S.; Huang, C.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J. Blessing or Curse? The Impacts of Non-Agricultural Part-Time Work of the Large Farmer Households on Agricultural Labor Productivity. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Du, H.; Wang, Z. Analysis of the Influences of Ecological Compensation Projects on Transfer Employment of Rural Labor from the Perspective of Capability. Land 2022, 11, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S. Labor Migration and Farmland Abandonment in Rural China: Empirical Results and Policy Implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.; Qi, Y.; Zeng, M. Labor Off-Farm Employment and Cropland Abandonment in Rural China: Spatial Distribution and Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yong, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhuang, L.; Qing, C. Rural-Urban Migration and Its Effect on Land Transfer in Rural China. Land 2020, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, D.; Yan, J. Evaluating the Impact of Land Fragmentation on the Cost of Agricultural Operation in the Southwest Mountainous Areas of China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Understanding the Difference between Standard Deviation and Standard Error of the Mean, and Knowing When to Use Which. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhou, P.; Zheng, S.; Li, Z. Cultivated Land Input Behavior of Different Types of Rural Households and Its Impact on Cultivated Land-Use Efficiency: A Case Study of the Yimeng Mountain Area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alin, A. Multicollinearity. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, M.R.; Acharya, P.; Sivo, S.A.; Xu, L. Number of Predictors and Multicollinearity: What Are Their Effects on Error and Bias in Regression? Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2019, 48, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sarkar, A.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Effects of Joint Adoption for Multiple Green Production Technologies on Welfare-a Survey of 650 Kiwi Growers in Shaanxi and Sichuan. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2021, 13, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, A.; Haselow, N.J.; Osei, A.K.; Villate, E.; Reario, D.; Kroeun, H.; SokHoing, L.; Uddin, A.; Dhunge, S.; Quinn, V. Homestead Food Production Model Contributes to Improved Household Food Security and Nutrition Status of Young Children and Women in Poor Populations. Field Actions Sci. Rep. J. Field Actions 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kamba, A.A.; Ojomugbokenyode, E.; Waziri, T.I.; Nabila, A. Socio-Economic Evaluation of Women Homestead Farmers in Zuru Emirate, Kebbi State, Nigeria. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Sci. 2021, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruba, U.B.; Talucder, M.S.A. Potentiality of Homestead Agroforestry for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Bangladesh Perspectives. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.R.; Khan, M.A. Impact of Household Interventions on Homestead Biodiversity Management and Household Livelihood Resilience: An Intertemporal Analysis from Bangladesh. Small-Scale For. 2023, 22, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, S.; Hennink, M.; Wendt, A.S.; Waid, J.L.; Kalam, M.A.; Gabrysch, S.; Sinharoy, S.S. Women’s Empowerment through Homestead Food Production in Rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mohanty, A.K.; Avasthe, R.K.; Shukla, G. Constraints Analysis in Adoption of Homestead Farming: A Case Study among Lepcha Community of Indo-Himalayan Region. Stud. Tribes Tribals 2017, 15, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Aurangozeb, M.K. Adoption of Integrated Homestead Farming Technologies by the Rural Women of RDRS. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, K.; Shahrier, M.; Karim, M.; Sarwer, R.H.; Phillips, M.J. Role of Homestead Farming Systems in the Livelihoods and Food Security of Poor Farmers in Southern Bangladesh; WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi, S.K. Coastal Homestead Farming Systems for Enhancing Income and Nutritional Security of Smallholder Farmers. In Transforming Coastal Zone for Sustainable Food and Income Security; Lama, T.D., Burman, D., Mandal, U.K., Sarangi, S.K., Sen, H.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Rada, N.E.; Wang, C.; Qin, L. Hired-labor Demand on Chinese Household Farms. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2012, 2, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Jin, M.; Zeng, L.; Tian, Y. The Effects of Parental Migrant Work Experience on Labor Market Performance of Rural-Urban Migrants: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sarkar, A.; Rahman, A.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Exploring the Drivers of Green Agricultural Development (GAD) in China: A Spatial Association Network Structure Approaches. Land Use Policy 2021, 112, 105827. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Zhao, G. Agricultural Land and Rural-Urban Migration in China: A New Pattern. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, J.O.; Torimiro, D.O.; Koledoye, G.F. Youth Migration and Agricultural Production: Analysis of Farming Communities of Osun State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2014, 18, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carte, L.; Schmook, B.; Radel, C.; Johnson, R. The Slow Displacement of Smallholder Farming Families: Land, Hunger, and Labor Migration in Nicaragua and Guatemala. Land 2019, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ng, Y.-K. Part-Peasants: Incomplete Rural–Urban Labour Migration in China. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2014, 19, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, S.; Davis, B.; Dewbre, J.; Handa, S.; Winters, P. Cash Transfer Programme, Productive Activities and Labour Supply: Evidence from a Randomised Experiment in Kenya. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 1172–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibbrandt, M.; Lilenstein, K.; Shenker, C.; Woolard, I. The Influence of Social Transfers on Labour Supply: A South African and International Review; Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, D.; Berry, H.L.; Schirmer, J. Farm Exit Intention and Wellbeing: A Study of Australian Farmers. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter-Leal, L.M.; Oude-Lansink, A.; Saatkamp, H. Factors Influencing the Stay-Exit Intention of Small Livestock Farmers: Empirical Evidence from Southern Chile. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 16, e0102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.G. Stay in Dairy? Exploring the Relationship between Farmer Wellbeing and Farm Exit Intentions. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 92, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Sarkar, A.; Qian, L. Evaluating the Impacts of Smallholder Farmer’s Participation in Modern Agricultural Value Chain Tactics for Facilitating Poverty Alleviation—A Case Study of Kiwifruit Industry in Shaanxi, China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tian, G.; Tian, Z.; Ren, Y.; Liang, W. Evaluation of the Coupled and Coordinated Relationship between Agricultural Modernization and Regional Economic Development under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Agronomy 2022, 12, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Sui, X.; Ye, B.; Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Zou, M.; Zhou, S. What Role Does Land Consolidation Play in the Multi-Dimensional Rural Revitalization in China? A Research Synthesis. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, C.; Song, W. Bibliometric Analysis in the Field of Rural Revitalization: Current Status, Progress, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Gohain, I.; Datta, M. Upscaling of Agroforestry Homestead Gardens for Economic and Livelihood Security in Mid–Tropical Plain Zone of India. Agroforest Syst. 2016, 90, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Area | Sample Size | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi Province | Xixiang County | 77 | 8.08 |

| Ziyang County | 107 | 11.23 | |

| Baihe County | 110 | 11.54 | |

| Hanbin District | 80 | 8.39 | |

| Sichuan Province | Wangcang County | 91 | 9.55 |

| Tongjiang County | 99 | 10.39 | |

| Emeishan City | 102 | 10.70 | |

| Anhui Province | Jinzhai County | 96 | 10.07 |

| Qimen County | 94 | 9.86 | |

| Huangshan District | 97 | 10.18 |

| Variable | Variable Meaning and Assignment | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homestead Exit Willingness | Unwilling = 0, willing = 1 | 0.261 | 0.440 |

| Willingness to withdraw from contracted land | Unwilling = 0, willing = 1 | 0.301 | 0.459 |

| Whole family labor transfer | The sum of incomplete labor transfer and complete labor transfer in households/total household population | 0.392 | 0.279 |

| Family incomplete labor transfer | The sum of the incompletely transferred labor force by households/total household population | 0.204 | 0.252 |

| Family complete labor transfer | The sum of the fully transferred labor force of the family/the total population of the family | 0.183 | 0.205 |

| Incomplete labor transfer of family women | The sum of the incomplete labor force transferred by women in the family/total population of the family | 0.062 | 0.130 |

| Household women complete labor transfer | The sum of the total labor force transferred by female households/total household population | 0.067 | 0.117 |

| Age of head of household | (years old) | 57.143 | 10.022 |

| Education level of the head of the household | Illiteracy = 1, primary school = 2, junior high school and technical secondary school = 3, high school = 4, junior college = 5, undergraduate = 5, master’s degree = 6 | 2.274 | 0.835 |

| The proportion of the elderly population | The sum of older people over the age of 60 in the family/the total population of the family | 0.898 | 0.895 |

| Sense of land control | Weak sense of land control = 1, average sense of land control = 2, strong sense of land control = 3 | 1.727 | 0.547 |

| Land size | (mu) | 15.486 | 20.494 |

| Land outflow scale | (mu) | 0.190 | 1.479 |

| Total household income | (10,000 yuan) | 9.663 | 13.046 |

| Clan | The surname does not belong to the big village surname = 0, and the surname belongs to the big village surname = 1 | 0.441 | 0.497 |

| Smartphone use | Very unfamiliar = 1, less familiar = 2, familiar = 3, somewhat familiar = 4, very familiar = 5 | 2.597 | 1.322 |

| Government interaction | Very little interaction = 1, less interaction = 2, average interaction = 3, more interaction = 4, less interaction = 5 | 2.039 | 1.012 |

| Government trust | The average value of three 5-level scales of trust degree of county government, township government, and village committee | 3.454 | 0.751 |

| Government obedience | Very bad = 1, poor = 2, fair = 3, better = 4, very good = 5 | 3.889 | 0.637 |

| Enthusiasm for participation in public affairs | Very low motivation = 1, poor motivation = 2, average motivation = 3, good motivation = 4, very good motivation = 5 | 3.080 | 1.085 |

| Universal trust | Most people in society are trustworthy, most people behave fairly and justly, and most of the time, people are helpful | 3.835 | 0.535 |

| Social Policy Implementation Evaluation | The average value of the 5-level scale of rural social policy satisfaction for rural pensions, rural medical insurance, and poverty alleviation and disability assistance | 3.726 | 0.751 |

| Environmental Policy Implementation Evaluation | The average value of the 5-level scale of rural environmental policy satisfaction for the two items of environmental pollution control and beautiful rural construction | 3.778 | 0.732 |

| Life satisfaction | The weighted average of three 5-level scales for quality of life, happiness, and future life | 3.611 | 0.562 |

| Perception of Welfare Gap between Urban and Rural Areas | Compared with the city, the average value of the 2 5 scales of farmer welfare and rural child development | 3.404 | 0.814 |

| Household purchase rate in villages and towns | Very low = 1, low = 2, average = 3, high = 4, very high = 5 | 2.143 | 0.928 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to Withdraw from Contracted Land | Homestead Exit Willingness | Willingness to Withdraw from Contracted Land | Homestead Exit Willingness | Willingness to Withdraw from Contracted Land | Homestead Exit Willingness | |

| Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | Coefficient (Standard Deviation) | |

| Whole family labor transfer | 0.512 *** (0.185) | 0.241 (0.184) | - | - | - | - |

| Family incomplete labor transfer | - | - | 0.612 *** (0.205) | 0.149 (0.205) | - | - |

| Family complete labor transfer | - | - | 0.622 ** (0.269) | 0.512 * (0.262) | - | - |

| Incomplete labor transfer of family women | - | - | - | - | 0.737 ** (0.357) | 0.186 (0.402) |

| Household women complete labor transfer | - | - | - | - | 0.818 ** (0.408) | 1.115 *** (0.395) |

| Age of head of household | −0.009 (0.006) | −0.006 (0.006) | −0.009 (0.006) | −0.006 (0.006) | −0.010 (0.006) | −0.007 (0.006) |

| Education level of the head of the household | −0.161 ** (0.064) | −0.082 (0.060) | −0.163 *** (0.063) | −0.079 (0.060) | −0.154 ** (0.063) | −0.078 (0.061) |

| The proportion of the elderly population | 0.181 (0.070) | 0.070 (0.071) | 0.187 *** (0.069) | 0.075 (0.070) | 0.153 ** (0.068) | 0.068 (0.068) |

| Sense of land control | 0.176 * (0.090) | 0.027 (0.092) | 0.175 * (0.090) | 0.023 (0.093) | 0.152 * (0.091) | −0.002 (0.094) |

| Land size | 0.014 (0.071) | 0.063 (0.067) | 0.019 (0.071) | 0.064 (0.067) | 0.006 (0.071) | 0.066 (0.067) |

| Land outflow scale | −0.035 (0.153) | 0.054 (0.145) | −0.033 (0.153) | 0.040 (0.147) | −0.046 (0.149) | 0.032 (0.148) |

| Total household income | −0.037 (0.068) | −0.056 (0.071) | −0.049 (0.073) | −0.090 (0.075) | −0.022 (0.066) | −0.080 (0.072) |

| Clan | 0.221 ** (0.088) | 0.221 ** (0.092) | 0.227 *** (0.088) | 0.223 ** (0.092) | 0.226 *** (0.087) | 0.226 ** (0.094) |

| Smartphone use | 0.091 ** (0.040) | 0.111 *** (0.042) | 0.091 ** (0.040) | 0.114 *** (0.042) | 0.088 ** (0.040) | 0.109 *** (0.042) |

| Government interaction | 0.095 * (0.051) | 0.185 *** (0.053) | 0.102 ** (0.050) | 0.185 *** (0.053) | 0.084 * (0.050) | 0.175 *** (0.053) |

| Government trust | 0.080 (0.078) | −0.062 (0.080) | 0.082 (0.078) | −0.060 (0.080) | 0.080 (0.079) | −0.056 (0.080) |

| Government obedience | 0.104 (0.079) | 0.051 (0.086) | 0.099 (0.079) | 0.054 (0.087) | 0.118 (0.081) | 0.054 (0.087) |

| Enthusiasm for participation in public affairs | −0.338 *** (0.047) | −0.399 ** (0.051) | −0.343 *** (0.048) | −0.397 *** (0.051) | −0.333 *** (0.047) | −0.396 *** (0.051) |

| Universal trust | 0.266 *** (0.098) | 0.146 (0.102) | 0.261 *** (0.097) | 0.154 (0.102) | 0.269 *** (0.097) | 0.154 (0.102) |

| Social policy implementation evaluation | −0.031 (0.069) | 0.118 (0.073) | −0.032 (0.070) | 0.118 (0.073) | −0.039 (0.069) | 0.110 (0.072) |

| Environmental policy implementation evaluation | −0.271 *** (0.075) | −0.285 *** (0.080) | −0.266 *** (0.075) | −0.285 *** (0.080) | −0.265 *** (0.076) | −0.284 *** (0.080) |

| Life satisfaction | 0.102 (0.096) | 0.038 (0.098) | 0.105 (0.097) | 0.049 (0.099) | 0.106 (0.097) | 0.050 (0.099) |

| Perception of welfare gap between urban and rural areas | 0.109 * (0.059) | 0.087 (0.061) | 0.111 * (0.059) | 0.082 (0.061) | 0.111 * (0.059) | 0.085 (0.061) |

| Household purchase rate in villages and towns | - | 0.103 (0.081) | - | 0.103 (0.080) | - | 0.102 (0.079) |

| Regional variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Athrho | 0.858 *** (0.074) | 0.858 *** (0.074) | 0.853 *** (0.074) | |||

| test (p-value) | 134.159 (0.000) | 133.605 (0.000) | 132.868 (0.000) | |||

| Wald chi2 | 213.88 | 213.74 | 221.86 | |||

| Prob | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, X.; Lu, Q.; Li, L.; Sarkar, A.; Li, H. Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach. Land 2023, 12, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081615

Ding X, Lu Q, Li L, Sarkar A, Li H. Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach. Land. 2023; 12(8):1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081615

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Xiuling, Qian Lu, Lipeng Li, Apurbo Sarkar, and Hua Li. 2023. "Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach" Land 12, no. 8: 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081615

APA StyleDing, X., Lu, Q., Li, L., Sarkar, A., & Li, H. (2023). Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach. Land, 12(8), 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081615